Tag: law

Upcoming workshop reminder: Copyright & Fair Use for Digital Projects

We just wrapped up three publishing workshops last week, but there’s more in store. Check out the details below and sign up for the next one offered by the Office of Scholarly Communication Services. See you there!

Copyright and Fair Use for Digital Projects

November 10, 2021

11:00am–12:30pm

RSVP

This online training will help you navigate the copyright, fair use, and usage rights of including third-party content in your digital project. Whether you seek to embed video from other sources for analysis, post material you scanned from a visit to the archives, add images, upload documents, or more, understanding the basics of copyright and discovering a workflow for answering copyright-related digital scholarship questions will make you more confident in your project. We will also provide an overview of your intellectual property rights as a creator and ways to license your own work.

Now available: Open educational resource of Building Legal Literacies for Text Data Mining

Last summer we hosted the Building Legal Literacies for Text Data Mining institute. We welcomed 32 digital humanities researchers and professionals to the weeklong virtual training, with the goal to empower them to confidently navigate law, policy, ethics, and risk within digital humanities text data mining (TDM) projects. Building Legal Literacies for Text Data Mining (Building LLTDM) was made possible through a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Since the remote institute in June 2020, the participants and project team reconvened in February 2021 to discuss how participants had been thinking about, performing, or supporting TDM in their home institutions and projects with the law and policy literacies in mind.

To maximize the reach and impact of Building LLTDM, we have now published a comprehensive open educational resource (OER) of the contents of the institute. The OER covers copyright (both U.S. and international law), technological protection measures, privacy, and ethical considerations. It also helps other digital humanities professionals and researchers run their own similar institutes by describing in detail how we developed and delivered programming (including our pedagogical reflections and take-aways), and includes ideas for hosting shorter literacy teaching sessions. The resource (available as a web-book or in downloadable formats including PDF and EPUB) is in the public domain under the CC0 Public Domain Dedication, meaning it can be accessed, reused, and repurposed without restriction.

In addition to the OER, we’ve also published a white paper that describes the institute’s origins and goals, project overview and activities, and reflections and possible follow-on actions.

Thank you to the National Endowment for the Humanities, the project team, institute participants, and staff at the UC Berkeley Library for making Building LLTDM a success.

[Note: this content is cross-posted on the LLTDM blog.]

Law & ethics in research and archiving social media of Myanmar resistance

On March 9, 2021, the Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Institute of East Asian Studies, the Institute of South Asia Studies, and the Human Rights Center at UC Berkeley hosted the online symposium Scholar-Activism and the Myanmar Resistance. The event invited scholar-activists to analyze and strategize for resistance to Myanmar’s military coup. The Office of Scholarly Communication Services collaborated with Dr. Hilary Faxon, Ciriacy-Wantrup Postdoctoral Fellow at UC Berkeley, to organize an afternoon workshop to explore the law, ethics, methods, and goals of archiving social media coverage of the coup.

Faxon highlighted that in the months since the military seized power on February 1, the internet has become a key domain of struggle in Myanmar. The military has cut off internet access and (before being banned) used Facebook to disseminate misinformation. Meanwhile, democracy activists have used social media alongside traditional tactics of street protests and general strikes to resist the regime.

The workshop brought together a diverse group of participants from across and beyond campus with perspectives from human rights, research and journalism, including WITNESS and Berkeley’s Human Rights Investigation Lab. Stacy Reardon, Literatures and Digital Humanities Librarian, discussed services and workshops offered by Digital Humanities at Berkeley, as well as tools used to conduct DH research, such as the Wayback Machine, Conifer, 4k download, Adobe Bridge, and others.

The Office of Scholarly Communication Services provided an overview for how to navigate law and policy issues when researchers are scraping, archiving, or text mining third party content, like social media posts, website text or images, or articles from databases. We addressed common issues that arise in research and archiving, including copyright, license agreements and website terms of use, privacy questions, and ethical considerations.

Workshop discussions were centered around a commitment to a shared ethics of care approach to using, sharing, and archiving information social media content related to the coup. The ethics of care framework suggests that what we do as information collectors or analyzers will affect other people, particularly when people have less structural power, and according to the ethics of care, we should care about that. This becomes immediately apparent when deciding whether or how to collect, process, and share potentially sensitive social media posts, images, and videos from the Myanmar coup, especially when doing so could have dire consequences for activists who are the subjects of those posts.

During the workshop, we talked about how the Library has adopted a form of ethics of care in our approach to making decisions about what collection materials we’ll digitize and put online. Our version of ethics of care is framed as a balancing principle: that is, we look to whether the value to researchers, the public, or cultural communities in digitizing and sharing the content outweighs the potential for harm or exploitation of people, resources, or knowledge.

Several takeaways emerged by the end of the workshop discussion:

- Protecting and defending human rights: Archiving material from social media—including videos, photos, and live streams—might help ensure perpetrators of violence are held accountable, but the production and circulation of such materials can also be highly-incriminating for media creators and platform users.

- Collecting is collaborative: Usage of archives is bound up with the intentions of those creating material, and so archiving requires an ongoing, bi-directional conversation between those creating content and those doing the archiving.

- Circumstances change: Both ethical and organizational approaches should be discussed and decided in advance of archiving. But expect situations to change – what is safe and straightforward to keep today may be more risky tomorrow.

- Capturing versus sharing: These are different processes, and “archiving” does not necessarily have to entail both. The benefits and risks associated with collecting data are distinct from those associated with sharing data or making it publicly available, so these processes should be considered separately.

- Law and ethics: Regardless of what is allowed under U.S. copyright law, there may be other contracts and terms of service that restrict what you can do with materials. Moreover, collecting voluntarily-released data may not violate legal privacy rights, but may present ethical questions.

- Data security: Develop a Data Management Plan that addresses organization and protection both during archiving, and after the project is completed. Consider a special purpose account for collaborations and data sharing.

- Data hygiene: Don’t collect more than you need.

- Practical strategies: Tools may depend on the specific goals of a researcher and the scale of the project. It is important to ask what, precisely, you mean when you say “archiving,” and what the purpose of creating your archive might be.

- Seek out a community of practice to support and situate your efforts.

We hope the workshop helped researchers to better understand the legal and ethical considerations in collecting, processing, and sharing potentially sensitive social media content of events like the Myanmar resistance. The Library and a broad community of supporters are here to help scholars address these challenges and equip them to proceed with confidence, care, and sound practices.

Robert Praetzel: Marin County Lawyer Who Stopped Marincello

New oral history interview: Robert Praetzel

for the book Legacy: Portraits of 50 Bay Area Environmental Elders

with text by John Hart, published by Sierra Club Books in 2006.

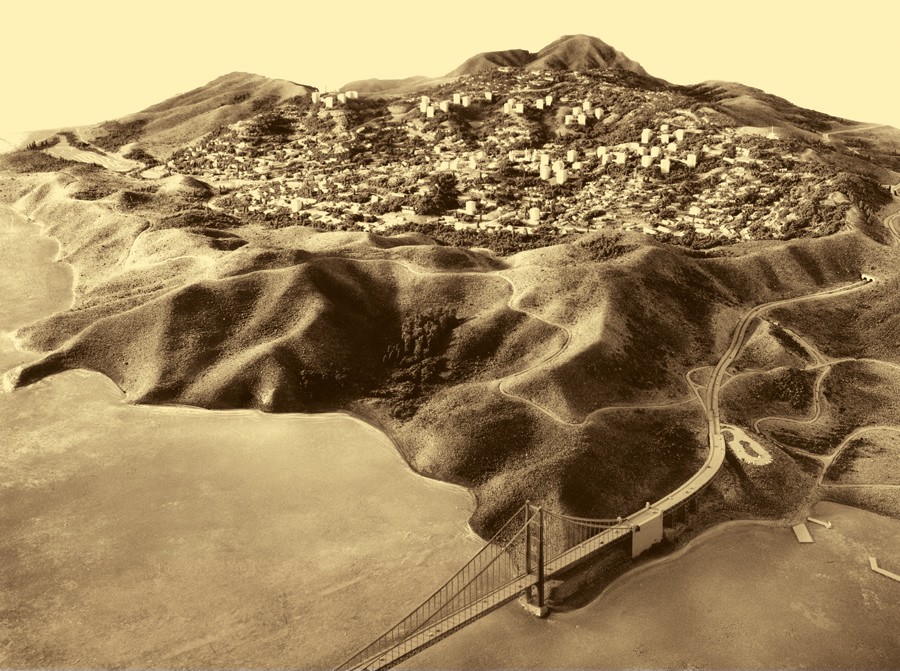

Robert Praetzel, a World War II veteran and graduate of UC Berkeley in 1950, is the Marin County lawyer responsible for stopping Gulf Oil’s Marincello real estate development in the late 1960s. The Marincello project would have built from scratch a new city in Marin County for some 30,000 people housed in fifty apartment towers, numerous single-family homes, low-rise apartments, and townhouses on 2,100 pristine acres in the Marin Headlands area. Today, thanks to Robert Praetzel’s fastidious and pro-bono legal work from 1966 through 1970, those lands are now preserved within the Golden Gate National Recreation Area. Praetzel and I recorded his four-hour-long oral history in the spring of 2019 at his home, nestled among the redwood trees on the slope of Mt. Tamalpais in Kentfield, Marin County, California. Praetzel’s 127-page transcript, complete with family photographs, adds important details to the broader story of how two major American cities, San Francisco and Oakland, came to have such exceptional tracts of preserved national park lands just minutes away from their urban centers.

preserved as Gerbode Valley in the Marin Headlands area of the Golden Gate National

Recreation Area.

Prior to recording Praetzel’s interview, the Oral History Center’s archives included a multi-narrator volume on Saving Point Reyes National Seashore, but not on the substantial Marin Headlands area that Praetzel helped preserve. Our oral history archive also includes previously recorded interviews with Martin Rosen, a conservation lawyer who worked in conjunction with Robert Praetzel; with Martha Gerbode, the philanthropist who helped purchase and preserve the land that Praetzel saved from development for inclusion in the Golden Gate National Recreation Area; as well as a Sierra Club oral history volume focused on the San Francisco Bay Area that references the Marincello real estate project that Praetzel defeated. Now, with the inclusion of Robert Praetzel’s oral history, the Oral History Center collection includes details of his dogged and pro bono legal efforts to preserve the Marin Headlands from the Marincello project, which also called for a “landmark hotel” atop the highest point in the Headlands as well as 250 acres for light industry, a mile-long mall lined with reflecting pools, and a square full of churches called Brotherhood Plaza. In the late 1960s, Robert Praetzel played an essential role in legally stopping this development project in what is now preserved as the Gerbode Valley and managed by the US National Park Service.

Robert Praetzel’s oral history also offers recollections from his youth in Marin County during the Great Depression (including eating a squirrel that his father hunted one Thanksgiving); his Navy service during World War II aboard a tanker-boat carrying highly explosive aviation fuel across the Pacific Ocean; his experiences as a student at UC Berkeley and UC Hastings College of Law in the late 1940s and early 1950s; as well as his marriage to fellow Berkeley alumnus, Nancy Donnelly Praetzel, with whom he raised a family in Marin County, all while building his eclectic legal career. In addition to detailing his victory against the Marincello development, Praetzel shared other stories from his legal career. One of those stories recounts his pro bono representation of environmental activists in 1969 who were arrested for obstructing logging trucks from felling a grove of redwood trees along the Bolinas Ridge in Marin County. Local newspaper clippings about the case are included in the appendix to Praetzel’s oral history, along with several photographs from Praetzel’s long, rich life.

I wish to thank Robert Praetzel and his wife Nancy Donnelly Praetzel for their patience this past year as we adjusted to the pandemic-induced realities of remote work while finalizing their oral history interviews. I also want to thank the anonymous donor whose generous gift to the Oral History Center made these interviews possible.

—Roger Eardley-Pryor, PhD

What happened at the Building LLTDM Institute

This update is cross-posted from the Building LLTDM blog.

On June 23-26, we welcomed 32 digital humanities (DH) researchers and professionals to the Building Legal Literacies for Text Data Mining (Building LLTDM) Institute. Our goal was to empower DH researchers, librarians, and professional staff to confidently navigate law, policy, ethics, and risk within digital humanities text data mining (TDM) projects—so they can more easily engage in this type of research and contribute to the further advancement of knowledge. We were joined by a stellar group of faculty to teach and mentor participants. Building LLTDM is supported by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Why was the Institute needed?

Until now, humanities researchers conducting text data mining in the U.S. have had to maneuver through a thicket of legal issues without much guidance or assistance. As an example, take a researcher scraping content about Egyptian artifacts from online sites or databases, or downloading videos about Egyptian tomb excavations, in order to conduct automated analysis about religion or philosophy. The researcher then shares these content-rich data sets with others to encourage research reproducibility or enable other researchers to query the data sets with new questions. This kind of work can raise issues of copyright, contract, and privacy law. It can also raise concerns around ethics, for example, if there are plausible risks of exploitation of people, natural or cultural resources, or indigenous knowledge.

Potential law and policy hurdles do not just deter text data mining research: They also bias it toward particular topics and sources of data. In response to confusion over copyright, website terms of use, and other perceived legal roadblocks, some digital humanities researchers have gravitated to low-friction research questions and texts to avoid making decisions about rights-protected data. When researchers limit their research to such sources, it is inevitably skewed, leaving important questions unanswered, and rendering resulting findings less broadly applicable.

Moving an interactive, design-thinking Institute online

After months of preparation, we had been looking forward to working and learning together at UC Berkeley, but the world had other plans for our Institute. Due to the global health crisis, we had to transform our planned in-person, intensive workshop into an interactive and relevant remote experience.

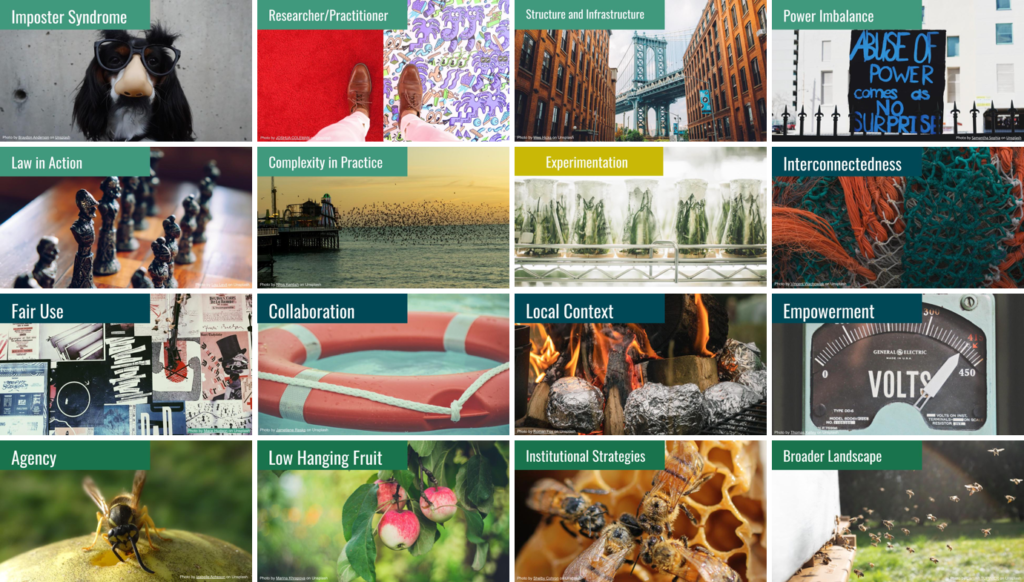

How did we do this? The pandemic meant we had to transition everything online, which of course presents challenges for a design-thinking framework. We are thrilled that our approach to interactive remote pedagogy was successful! (You can check out the schedule and framework in our Participant Packet.) The substantive content was pre-recorded and delivered in a flipped classroom model. Faculty created a series of short videos, and shared readings relevant to the legal literacies. We also provided the video transcripts and slides to participants to promote accessibility and accommodate multiple learning styles.

We used Zoom to meet synchronously for discussion in groups of various sizes. We used Slack for asynchronous communication, and interactive tools such as Mural for design thinking exercises like journey mapping so that everyone could live edit and collaborate. We capped each day with a “happy half hour” on Zoom as an informal way to get to know each other a little better, even from afar.

We also relied on an institute moderator and daily writing exercises to reinforce the design-thinking stages and learning outcomes. Each night, we reviewed the participants’ free-writes and began the next morning by reflecting back to the participants the themes from what they had shared.

Reflections on goals: social justice & effective empowerment

One of our priorities for the Institute was to invite a diverse pool of participants, including those involved in social justice research, in order to maximize the public value impact of Building LLTDM. We looked for demonstrated commitments to diversity and equity but could hardly have imagined the breadth and depth of experiences that applicants were willing to share. The selected participants research everything from understanding “place” data from community histories of historic African American settlements to the development of AIDS activist networks in communities of color; to portrayals of autism in literature; and more. Others demonstrated a commitment to bringing back the skills they learn to expand TDM opportunities for students and communities who have traditionally been marginalized or under-resourced. They also came from a variety of institution types, from research advising and support experience, professional roles, levels of experience with TDM, career stages, and disciplinary perspectives.

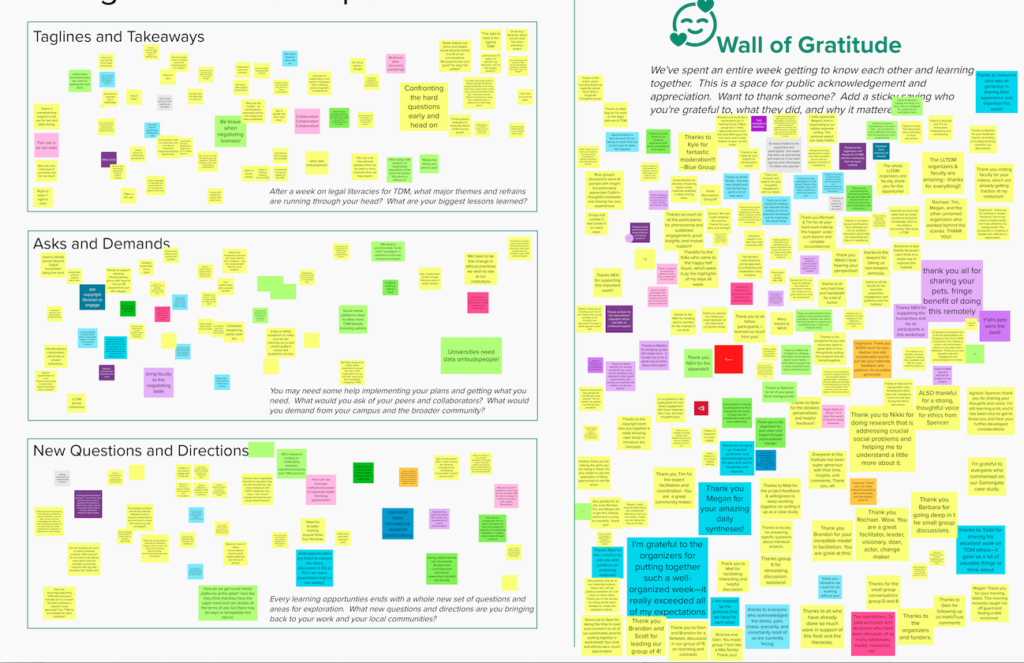

We are also moved by the participants’ own reflections on the experience. One of the last interactive exercises we hosted during the online Institute was a collective week-in-review discussion, and gratitude wall. We asked the participants to share what they were thankful for, highlighting other participants where possible. So many of the participants wrote about how valuable the learning experience was and how thoughtfully it was put together and delivered.

We can’t express the transformational impact of the week better than the participants, themselves. In Institute evaluation forms, they shared feelings like:

- “This is by far the best organized event that I have ever attended. The content was by far the most substantive. The faculty were by far the most engaged. A+ across the board.”

- “I am so grateful to have had the opportunity to engage with a diverse group of scholars (researchers and professionals)… The deliberately thought through breakdown and mix fostered incredibly valuable discussions and I would hope this kind of framework is used as a best practice for future DH institutes of all kinds going forward. Also, thank you for such an amazing virtual experience which I can only imagine took a tremendous amount of work to coordinate and plan with limited time to shift to an entirely different format–I was overjoyed to critically engage with complex subjects…”

- “This has been phenomenal. I don’t want to qualify it (by adding something like “…for having to be moved online”), because it’s been so, so good: well organized, thoughtful, and human throughout.”

- “There was clearly so much thought, care, and planning that went into the preparation of this institute, and it was an amazing opportunity to learn from a group of people — organizers, faculty, and participants — who all have such deep expertise. The video and readings lists alone are a huge resource, but to be able to process and reflect on that material together with a diverse group of people was really wonderful.”

Next steps, and our own gratitude

What’s next for Building LLTDM? The “Institute” is not over yet; only the 1-week training is complete. The cohort will be meeting again virtually in February 2021 to discuss how implementation of the literacies into our local communities and practices has gone. In the meantime, as the participants bring back the law and policy literacies they’ve learned to their home institutions, we are excited to see several cohort members already organizing their own post-Institute research subgroups, such as those whose TDM work relies heavily on social media content, and others who are exploring how to disseminate the Building LLTDM literacies within other instructional formats and frameworks.

As part of the grant, the project team will also be aggregating the resources from the Institute and developing supplementary material for an Open Educational Resource (OER). We know there is a large community of TDM researchers and professionals who may be interested in or who can benefit from these materials, and the OER will be made available for broad reuse in the public domain.

Thank you to all the participants for their insights and contributions, willingness to share, and flexibility in transitioning to a fully-remote Institute. Thank you to all the faculty for their unmatched legal and policy expertise, ongoing commitment to mentorship, and adaptability in content creation and delivery. And thank you again to the NEH for making such a meaningful experience possible.

New Release Oral History: Marshall Krause, ACLU of Northern California Attorney and Civil Liberties Advocate

The Oral History Center is pleased to release our life history interview with famed civil liberties lawyer, Marshall Krause.

Marshall Krause served as lead attorney for the ACLU of Northern California from 1960 through 1968 and subsequently served as an attorney in private practice where he continued to work civil liberties cases. Krause attended UCLA as an undergraduate and graduated from Boalt Hall, UC Berkeley School of Law after which he clerked for Judge William Denman and Justice Phil Gibson.

In this oral history, Mr. Krause discusses: his upbringing and education, including his time at Boalt Hall; clerkships with judges Denman and Gibson and how those experiences influenced his progressive political outlook; his tenure as ACLU staff attorney, including many of the cases he worked; his experiences arguing several cases before the United States Supreme Court; his perspective of the San Francisco counterculture of the 1960s; and his professional and legal career after leaving ACLU in 1968, which included arguing additional cases before the US Supreme Court.

This oral history is significant for any number of reasons, but it is especially worthwhile for anyone interested in the current state of battles around the freedom of speech — from obscenity through political speech — and how these were decided in the courts in decades past, establishing the precedents under which we live today.

Martin Meeker