Tag: conservation

Primary Sources: Environmental History: Conservation and Public Policy in America, 1870-1980

Environmental History: Conservation and Public Policy in America, 1870-1980 is a digital archive from Gale that provides access to sources documenting the emergence of conservation movements and the rise of environmental public policy in North America from the late 19th to the late 20th century.

The archive offers an incisive view into the efforts of individuals, organizations, and government agencies that shaped modern conservation policy and legislation. It includes:

- Papers of early environmentalists like George Bird Grinnell, a founding member of the Boone and Crockett Club and the first Audubon Society, and Joseph Trimble Rothrock, known as the “father of forestry.”

- Records of the American Bison Society, which helped save the American bison from extinction, and papers of women conservationists like Rosalie Edge and Velma “Wild Horse Annie” Johnston.

- Documents from the U.S. Forest Service, U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, and various state and municipal agencies focused on conservation and land-use matters.

- Grey literature from advocacy organizations, study groups, and commissions covering wildlife management, land preservation, public health, energy development, and more.

This archive provides valuable context for understanding today’s environmental challenges by chronicling the historical struggle to balance economic exploitation and resource conservation. It offers insights into the grassroots movements, advocacy efforts, and policy decisions that laid the foundation for modern environmental protection.

The resource includes grey literature on conservation and environmental policy from UC Berkeley’s Institute of Governmental Studies Library.

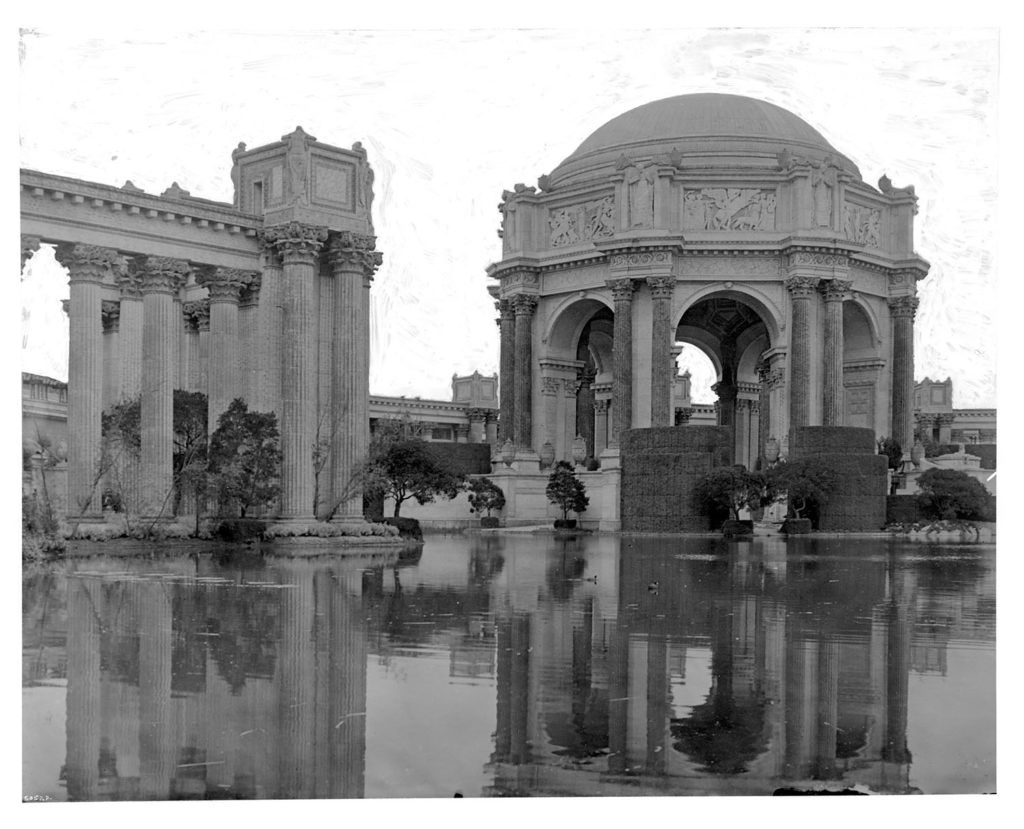

Now Online: Images from Glass Negatives of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition

The Bancroft Pictorial Processing Unit is proud to announce that The Edward A. Rogers collection of Cardinell-Vincent Company and Panama-Pacific International Exposition Photographs has been organized, archivally housed, individually listed, and made (substantially) available online. This work was accomplished over two years, thanks to grant support from the National Endowment for the Humanities and, of course, careful hard work on the part of many library staff.

In this blog posting, Project Archivist Lori Hines describes some of the most challenging (and rewarding) work; preserving and providing access to fragile and often damaged glass negatives.

Handling Glass Plate Negatives: A Lesson in Mindfulness

The Rogers collection of Panama Pacific International Exposition photographs, received as a gift in 2014, includes over 2,000 glass negatives. These fragile items required special handling and archival containers with padding. Hardest to work with were approximately 150 oversize glass negatives ranging from 11 x 14 inches to 12 x 20 inches. Antique glass can become brittle and, of course, is heavy. From handling to wheeling the negatives back and forth to the conservation department and the digital lab, one had to be very conscious of every move and step taken.

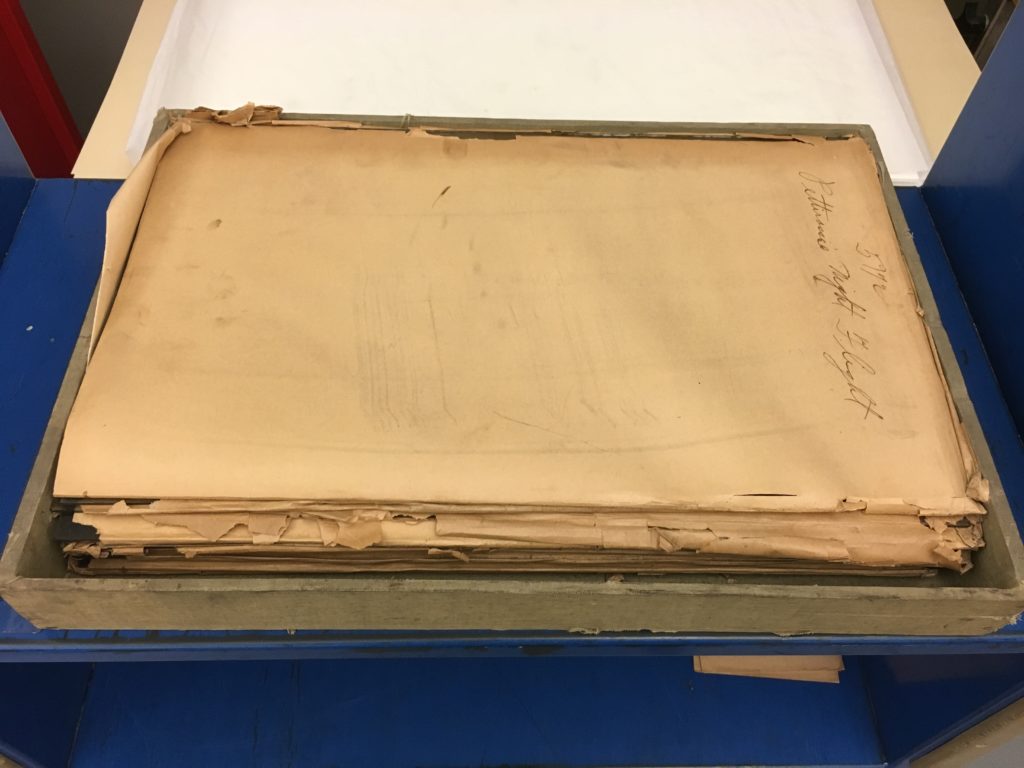

This first photo shows how the negatives were received in the library. Note they have no padding between the plates and there are only original, brittle sleeves to protect them. A stack of ten or fifteen is very heavy and getting your fingers under one, to lift it off the stack, is challenging. The weight of the negatives on top of each other is also a risk — the antique glass can easily crack under the weight.

This photo shows how the negatives have been housed by library staff; vertically with corrugated archival cardboard around each. Our library conservators designed the housing to limit box weight, to provide protective padding, to protect the plates from abrasion as they’re removed, and to make handling safer.

The largest plates, at 12 x 20 inches, needed another housing solution because it was impractical to store them upright, but the weight of one on another was a concern. The Library’s Conservation Department built custom trays to hold each 12 x 20 negative, with just three plates (and their trays) in an archival box that is stored flat on a cabinet shelf.

The negatives are handled on the long side of the glass to offer best support and, during the cleaning, housing, and inventory process, are rested on a piece of thin foam padding to buffer any impact with the work table.

About 10% of the negatives arrived broken. To be digitized, we had to re-piece the broken negatives together on a supporting sheet of glass, like a puzzle, then hand it off immediately to the photographer in the Library’s Digital Imaging Lab. The glass sheet with the broken negative on top was then placed on a light table, so it was lit from behind, to be captured by the digital camera. The light table and camera are visible in the background of this image.

The results were often quite satisfying, as can be seen in this example of a badly broken glass negative that was pieced together.

The finding aid describing and listing the entire Rogers collection, with more than 2,000 digital images, may be viewed at the Online Archive of California.

To browse examples of images scanned from broken plates, try searching the finding aid for “negative is broken”, and navigating through the results, or by browsing this Calisphere website search that retrieves just the broken-plate images.

Special thanks go to Christine Huhn and the staff of the Digital Imaging Lab; Hannah Tashjian, Erika Lindensmith, Martha Little, and Emily Ramos of the Conservation Department; staff of the Library Systems Office and the California Digital Library that worked with us to get the material online; to Gawain Weaver Art Conservation (contractors for preservation and scanning of panoramic film negatives), and to the Bancroft Pictorial Unit team that devoted much or their 2016-2018 work life to this effort: Lori Hines, Lu Ann Sleeper, and a crew of student staff.

Getty Oral Histories: Jim Druzik and Neville Agnew

We are pleased to announce the release of two new oral histories in our continuing partnership with the Getty Trust to document the careers of extraordinary artists, scientists, preparators, scholars, and administrators that have guided and shaped the Getty over the past thirty years. Historians Todd Holmes and Paul Burnett spent four days alternating full-day interview sessions in an intense baptism into the world of conservation science, exploring the careers of two remarkable scientists from the 1960s through to the present: Jim Druzik and Neville Agnew.

Foxes and Hedgehogs: Jim Druzik and the Development of the Field of Conservation Science

Getty Conservation Institute Senior Scientist Jim Druzik had a baptism of his own rubbing shoulders with the geniuses of postwar modern art as they worked together on installations at the Pasadena Museum of Modern Art. Trained as a chemist, and with one foot ever in the scientific world, Jim very quickly applied the latest scientific research to the problems of conservation. He joined the Getty Institute of Conservation in 1985, and soon established himself as a world leader in conservation science, always concerning himself with how the physical and chemical composition of museum artifacts reacted with the physical and chemical composition of their environments. But much more than that, Druzik was a student of the larger social and economic context of the museum world, taking advantage of initiatives in pollution research, assessments of industrial chemicals, and energy conservation, to name just a few, to make the museum world a better, more accessible and sustainable place. Finally, Jim is very reflective about his roles as a scientist and an administrator. He understands that the world of science and the world of the museum are defined by the people who work in them and on them. Science is social, as the historians are fond of saying, and the keys to Jim’s success can be found as much in his enthusiasm for the people he works with as for the work he does with them.

Neville Agnew: Thirty Years of Cultural Heritage Site Conservation with the Getty Trust

South-African-born Neville Agnew is a more nomadic scientist. If Jim’s work brings laboratory tools to the museum environment, Neville’s brings lab techniques and tools far out into the field. Whether raising and preserving the guns of a long-lost naval vessel off the north coast of Australia, or studying the deterioration of the Great Sphinx in Egypt, or restoring ancient Buddhist cave paintings in southwestern China, Neville underscores the fact that international conservation work is not just bringing the tools of the laboratory to bear on ancient sites, but also a skillful diplomatic effort to build and maintain the partnerships—between project sponsors, international conservation research teams, national political leaders, and local communities—needed to conduct such work. He explores the tension between an ideal of conservation in controlled environments versus the compromises inherent in dealing with “immovable cultural property.” At a time when the willful destruction of cultural heritage is almost a daily news item, we are reminded of the importance and fragility of the work that both of these scientists have done to protect the world’s art and cultural heritage for future generations.

Paul Burnett and Todd Holmes, Historians/Interviewers, January 2017

Protecting the California Coast: New Interviews with Joe Bodovitz and Will Travis

Just over 50 years ago the California State Legislature established the Bay Conservation and Development Commission (BCDC). This commission was charged with protecting the San Francisco Bay from unchecked development and with providing access to this great natural resource. In 1972, citizens throughout California voted to establish the Coastal Commission, which had a charge similar to the BCDC but its authority ran the entire coastline of California. Today we are pleased to release to new oral history interviews with two of the most important figures in both of those organizations: Joe Bodovitz and Will “Trav” Travis.

Joseph Bodovitz was born Oklahoma City, Oklahoma in 1930. He attended Northwestern University, where he studied English Literature, served in the US Navy during the Korean War, and then completed a graduate degree in journalism at Columbia University. In 1956 he accepted a job as a reporter with the San Francisco Examiner, reporting on crime, politics, and eventually urban redevelopment. He then took a position with SPUR (San Francisco Planning and Urban Research) where he launched their newsletter. In 1964 he was enlisted to lead the team drafting the Bay Plan, which resulted in the creation of the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission (BCDC) by the state legislature in 1969. Bodovitz was hired as the first executive director of BCDC. In 1972 he was hired by the newly-established California Coastal Commission to be its first executive director. He left the Coastal Commission in 1979 and shortly thereafter was named executive director of the California Public Utilities Commission, a position he held until 1986. He served as head of the California Environmental Trust and then as the project director for BayVision 2020, which created a plan for a regional Bay Area government. In this interview, Bodovitz details the creation of the BCDC and how it established itself into a respected state agency; he also discusses the first eight years of the Coastal Commission and how he helped craft a strategy for managing such a huge public resource ? the California coastline. He further discusses utilities deregulation in the 1980s and the changing context for environmental regulation through the 1990s.

Will Travis was born in Allentown, Pennsylvania in 1943. He attended Penn State University as both as an undergraduate and graduate student, studying architecture and regional planning. From 1970 to 1972 he worked as a planner for the then nascent San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission (BCDC). In 1972 moved to the newly established California Coastal Commission, where worked in various capacities until 1985. In 1985 Travis returned to BCDC first as deputy director then as the agency?s director beginning in 1995. He retired from BCDC in 2011 and continues to work as a consultant. In this life history interview, Travis discusses his work both the BCDC and the Coastal Commission, focusing on accounts of particular preservation and development projects including the restoration of marshland areas around the San Francisco Bay. The interview also covers in detail Travis?s work documenting the threat of sea level rise as a result of climate change and how the Bay Area might plan for such a transformation.