Interconnections

By Roger Eardley-Pryor, PhD

Interconnections in oral histories are like the Baader-Meinhof Phenomenon: once you notice them, you start seeing them everywhere. At least that’s how interconnections appear to me, both within and between some of our oral history projects. Webs of connection within a single oral history are sometimes overt—like when Sierra Club leader Aaron Mair hitched together the thoughts of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. with the words of John Muir, all while discussing inherent intersections between voting rights, civil rights, and environmental justice. Other interconnections, as you’ll read below, demand a bit of digging. However, once you scratch the surface, they’re like the root system for Quaking Aspen trees: it’s all interconnected down below.

Quaking Aspens are the state tree of Utah, a place where I discovered some fascinating relationships between a few of our recent oral history projects. Hop along this interconnected oral history journey, with stops at a proposed power plant near a national park, then to a desert community in central Utah that twice experienced a major influx of new residents, which will bring us back to a new project the Oral History Center recently began. Along the way, we’ll examine environmental laws on air quality, lobby a few Senators, construct a coal-fired power plant, confront racist wartime hysteria, and seek contemporary healing from crimes of the past. I hope this journey leaves you with a sense of how oral histories reveal relationships between people and places, and how our sense of belonging to both evolves and intersects across space and time.

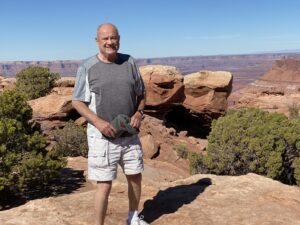

This journey begins with my interview with Tony Ruckel, another Sierra Club leader who, like Aaron Mair, was eventually elected president of the Club. Before that, in the 1970s, Ruckel founded and became director of the Rocky Mountain Regional Office for the Sierra Club Legal Defense Fund (SCLDF). The SCLDF, now called Earthjustice, was one of the nation’s first public interest environmental law organizations and, coincidentally, has many of its files archived in The Bancroft Library. Ruckel and his Rocky Mountain Regional Office handled all Sierra Club litigation from the northern plains, throughout the Rocky Mountains, and down to the desert southwest, including the red-rock canyonlands of southern Utah. A rouge riot of river-hewn rock undulates through southern Utah in streams of stone that reveal layers from eons upon eons of Earth. Wind-worn gorges where scrub brush and pine cling to canyon sides erupt in spires and stone arches of stark beauty and worldly wonder, such that several national parks aim to preserve that erosional landscape. During the energy crises of the 1970s, some of Ruckel’s legal campaigns featured battles against the Intermountain Power Plant, an enormous coal-fired electricity plant proposed just outside of scenic Capitol Reef National Park in southern Utah.

The early plans for the Intermountain Power Plant near Capitol Reef would have created one of the largest coal-fired facilities ever built with four giant smoke-stacks belching pollution into the air. As Ruckel recalled, “Originally, it was proposed at five thousand megawatts. Well, nobody’s ever tried to build a plant that size…. So, then they carved it down to three thousand megawatts.” Most of those megawatts would be sent by wire to sprawling southern California for purchase by L.A.’s Department of Water and Power, with additional power purchased by the municipalities of Anaheim, Burbank, Glendale, Pasadena, and Riverside. “It was clear California didn’t want to build this stuff,” Ruckel noted, “they just wanted to consume the energy.” To combat the giant coal plant near Capitol Reef, Ruckel’s legal strategy relied in part on the relatively recent Clean Air Act of 1970, which had surprisingly sharp teeth and a wide scope for federal regulation and enforcement.

The Clean Air Act of 1970 required the federal government to not just improve air quality in polluted areas, but it demanded the “prevention of significant deterioration of air quality” in areas that already had clean air, like at Capitol Reef National Park. However, in 1977, as Ruckel worked to halt the power plant in southern Utah, the Clean Air Act came up for Congressional review. The US House of Representatives rushed through new amendments and, as Ruckel told it, “lo and behold, there was nothing regarding the prevention of significant deterioration in the new statute … the language supporting it had been removed in the amendments.” Ruckel quickly shifted gears and, with help from Friends of the Earth, mounted a lobbying campaign in the US Senate to reinstate prevention of significant deterioration of air in amendments. “The result of the lobbying,” Ruckel explained, “was we certainly educated a ton of Senate staffers, particularly, and a few critical Senators. And as it resulted, that turned out to be enough.” The final 1977 Clean Air Act amendments re-inserted language on the prevention of significant deterioration of air, which pushed the Intermountain Power Plant toward a different construction site away from southern Utah’s pristine national parks. In the early 1980s, plans for the power plant moved north to the desert of central Utah near a town named Delta, which provides the next stop on our interconnected journey between Oral History Center projects.

Tony Ruckel’s efforts to move the Intermountain Power Plant away from southern Utah’s national parks produced significant demographic and social changes in the small desert community of Delta in central Utah. In 1981, during groundbreaking ceremonies for the Intermountain Power Plant, the population of Delta City was 1,930. Over the next few years, Delta’s population exploded with 6,000 new construction workers and their families who struggled to find temporary housing, often living in burgeoning mobile home parks or in motel rooms. Delta’s over-crowded classrooms benefited from new school construction, paid with nearly $8 million in mitigation funds from the Intermountain Power Plant, which also helped build a new city hall. In 1984, a new hospital broke ground in the town of Delta in addition to sewer and water system improvements, enhanced police protection, and new vocational education opportunities funded in part by the power plant. But even as local incomes rose, so did crime rates and, after Delta’s long standing ban on Sunday alcohol sales was repealed in 1983, liquor purchases more than doubled. After the power plant’s first coal-fired unit came on line, a formal dedication of the project held in 1987 saw an estimated 8,000 people attend. The tiny Delta airport handled fifty-two private airplanes, which required hiring an air traffic controller in a temporary tower built for the occasion. The Mormon Tabernacle Choir sang, and the President of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints came down from Salt Lake City to offer a dedicatory prayer. In the 1980s, after inviting the Intermountain Power Plant to Delta, the town transitioned temporarily from a dozy desert community to a bustling boomtown. A swift sense of change swept through Delta’s desert community like a flash-flood through a slot canyon.

Those developments in Delta during the 1980s spurred some longtime residents to preserve parts of its dwindling past. When local residents launched a drive to retrieve and preserve an 1893 Case tractor in the county, they sparked interest in building an historical center to house such artifacts. The Great Basin Museum and the Great Basin Historical Society were both founded in the mid-1980s. And in over-subscribed journalism classes at Delta High School, teachers aimed to engage new students in the local history of their new hometown. Students began interviewing Delta’s local elders for the school paper and learned that many longtime residents had memories and historical artifacts from an American race-based prison camp constructed during World War II just a few miles outside of Delta, Utah.

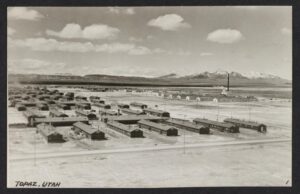

Back in February 1942, just 10 weeks after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 authorizing the exclusion of all persons of Japanese ancestry from “prescribed military areas.” More than 110,000 Japanese American citizens—men, women, and children—were forced from their homes in Western portions of the country to incarceration camps built in desolate areas of the United States. One such Japanese American incarceration camp was built hastily in the remote desert of central Utah, sixteen miles from Delta. The “Central Utah Relocation Center,” more commonly called Topaz, was designed to house 9,000 prisoners in forty-two blocks of make-shift housing units. During its three years of operation, Topaz imprisoned 11,212 individuals due to their race and family ancestry. Most were American citizens. In the early 1940s, the influx of imprisoned Japanese Americans at Topaz made it the fifth-largest community in Utah before the camp closed and was disassembled in October 1945.

In the early 1980s, the influx of new residents to central Utah for the Intermountain Power Plant sparked renewed interest in Delta’s local history, including that of Topaz and the people affiliated with it. In 1983, survivors of incarceration at Topaz and residents in Delta together created the Topaz Museum Board as a 501(c)(3) organization to formally collect stories and artifacts for an eventual museum in Delta. Around the same time, longstanding protests by Japanese Americans demanding financial redress for their mass incarceration without due process gained new traction. In 1980, the US Congress and President Jimmy Carter approved creation of a Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC). The Commission’s report, released in late 1982 and titled Personal Justice Denied, denounced the injustice of mass exclusion, removal, and detention of Japanese Americans and concluded the government’s policies were caused not by “military necessity” but by “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.” The Commission’s recommendations eventually culminated in passage of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which provided a national apology and individual reparations of $20,000, known as redress, that were delivered to survivors of that imprisonment.

The redress movement in the 1980s encouraged renewed reckoning with one chapter from the long, dark history of American racism, but over time Americans’ knowledge of Japanese American incarceration appeared to fade. Nearly twenty years after redress, Congress passed the Preservation of Japanese American Confinement Sites (JACS) Act of 2006, which established a $38 million matching-grant program to identify, collect, and preserve stories, artifacts, and historic sites connected to the World War II incarceration of Japanese Americans. The Topaz Museum Board in Delta, Utah, submitted an early JACS grant and, after many years of effort, the Topaz Museum opened to the public in 2017. One of the museum’s founders wrote, “If you visit the museum, you might be able to sense the complexity of the deeply troubling history of Topaz. We hope you will be convinced that we all have an obligation to prevent anything like it from happening again.”

Here’s where the points along our journey connect back to Berkeley’s Oral History Center and to The Bancroft Library. Almost ten years ago, the Oral History Center also earned a JACS grant to conduct oral histories with Japanese Americans who attended UC Berkeley before—and in some cases after—their incarceration during World War II. That initial oral history JACS project coincided with The Bancroft Library’s separate JACS grant to digitize and make available online the library’s extensive Japanese American incarceration materials, which have now become The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Digital Archive. Many of those materials will be used in a forthcoming exhibition titled, “Uprooted: The Incarceration of Japanese Americans,” which will open this October in The Bancroft Library.

At the same time, the Oral History Center is now in the early stages of a new JACS project titled “Healing Intergenerational Wounds of Japanese American Confinement?: Private and Public Memory at Manzanar and Topaz.” During the pandemic year of 2020, the Oral History Center submitted a JACS grant proposal focused on two of the ten Japanese American prison camps during World War II: Manzanar in southeastern California, and Topaz in central Utah. In May of 2021, the same month the Oral History Center published our interview with Tony Ruckel for the Sierra Club Oral History Project, we learned our JACS grant proposal was successful!

The heart of our newest JACS project asks, how do people heal? In collaboration with Japanese American advisors and partners, we will conduct new oral history interviews, produce a new Berkeley Remix podcast series based on those interviews, and create graphic narrative artwork to document and disseminate the ways in which intergenerational trauma and healing occurred after the U.S. government’s incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. With narratives of healing as our project’s through line, we will interview descendants of those involved in the redress movement who initiated the conversation around healing; individuals who relate to their Japanese American heritage and incarceration history through popular culture; and those who interpret these stories of trauma and empowerment at incarceration sites and beyond. We will investigate the impact of different types of healing, how this informs collective memory, and how these narratives change across generations. The oral histories conducted for this JACS project will examine and compare how private memory, creative expression, place, and public interpretation intersect at the Manzanar and Topaz prison camps. We hope that preserving and sharing this myriad of voices from an intergenerational spectrum of experiences—both historic and contemporary—will provide an accessible way for society to engage with America’s fraught past with Japanese American incarceration.

Writer and Sierra Club member Wallace Stegner, whose interview with the Oral History Center is titled “The Artist as Environmental Advocate,” wrote an essay in 1986 titled “The Sense of Place.” “It is probably time we looked around us instead of looking ahead,” Stenger wrote, “to learn that place’s history and to … acquire the sense not of ownership but of belonging.” Who belongs to a place, what belongs, and how they belong—or how they do not—are all questions that echo across the oral history journey recounted in this post, particularly as they reverberate in the canyons and over the deserts of Utah. But questions of belonging and place animate all of American history. Indeed, that is the story of humankind.

The stories of how people make sense of their place in the world, and how their sense of belonging changes over time, is exactly what we try to record at the Oral History Center. I’ve learned from preserving and promoting these stories that, almost always, they are interwoven in intricate and unexpected ways. As Dr. Martin Luther King wrote in 1963 from a jail cell in Birmingham, “I am cognizant of the interrelatedness of all communities and states.” King continued, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny.” Former Sierra Club president Aaron Mair, in his oral history, connected King’s thoughts to words scribbled in a journal by eventual Sierra Club founder John Muir nearly one hundred years earlier. In 1869, while spending a transformative summer living in the Yosemite Valley, Muir wrote, “When we try to pick out anything by itself we find that it is bound fast by a thousand invisible cords that cannot be broken, to everything in the universe.”

Interconnected threads such as these between people, places, and projects at the Oral History Center weave a remarkable tapestry through time. The more time you spend exploring our incredible archive of oral history interviews, the more intricate and meaningful these connections begin to appear. This month, as a new academic year begins and students and staff physically return to Berkeley—with many first and second-year students stepping foot on campus for the very first time—I encourage you to dive into our collection and see what kinds of interconnections might appear.

Find these and all the Oral History Center’s interviews from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. To ensure a full text search, on the next page scroll down and toggle on the button that says “full text.” You can also visit all our collection guides and our projects page to find oral histories on specific subjects. We have oral histories on just about every topic imaginable.

— Roger Eardley-Pryor, PhD