Tag: Music

From the Oral History Center Director — July 2021

From the Oral History Center Director — July 2021

I recently had the pleasure of watching a new documentary film, The Sparks Brothers (2021), which details the solidly unconventional musical career of Ron and Russell Mael, lifetime stalwarts of the band Sparks. This film has everything one might want from a rock and roll documentary: rare footage of live performances, insightful commentary from artists influenced by the band (Beck, Bjork, Weird Al), and a narrative charting several artistic ups and downs. You might watch it and think that you caught an episode of “Behind the Music” (without the cliche visits to Betty Ford) or This is Spinal Tap (the new wave remix). But the thing about this film that really caught my attention — and got me thinking about our work at OHC — is how revealing and edifying a full life history can be (as is done with The Sparks Brothers as well as with many of our oral histories).

Growing up in California in the early 1980s, Sparks originally came to me as another hip, ironic, proudly nerdy Los Angeles new wave band. Surely the first song of theirs I heard was “Cool Places,” an absurdly upbeat synthpop song performed with and co-written by Jane Weidlin of the Go-Go’s. I saved my pennies and soon purchased the album (Sparks in Outer Space) and loved most every song. I followed their career through another few albums then, as teenagers do, moved on to other bands and sounds. To me Sparks remained in my memory as a genre-band — a very good one, but still one of a particular type.

Watching this full-life documentary, however, upset my own memories of this band. It revealed parts of their lives (including telling moments of their childhood) that were unknown to me. It showcased their early years as a Zappa-like freak band, their move to England where they earned fans as glam-rockers, their burgeoning interest in synthesizers and ultimately their collaboration with synth-god Giorgio Moroder, and finally their return to Los Angeles and reincarnation as a new wave band. The film also details the years since the 1980s, which took the pair in even more esoteric musical directions while continuing to win new fans, garner critical accolades, and stage frankly amazing artistic achievements. After watching this video, I am now eager to dig deeper into their music and thus discover bits of pop music past that thus far had been hidden to me. New music need not emanate from this day and age after all.

This is one of the reasons that I think the life history interviews we do at the Oral History Center are so incredibly valuable. When we conduct this type of oral history (ten hours or more with a single individual) we not only have the opportunity to ask the obvious questions (“tell me about the research that led to your Nobel Prize?” “What was it like to win at the Supreme Court?”), we are afforded the freedom to explore the lesser known aspects of a narrator’s life. With the additional hours of interviewing, we can document the narrator’s family background, upbringing, and education. We can detail early career moves that maybe didn’t amount to much but which taught crucial life lessons. We can document failures as well as successes. In my interview with Herb Donaldson, the first gay man appointed as a judge in California, I also learned about his side job as a coffee importer and roaster who gave key advice to a certain coffee shop getting started in Seattle (yes, Starbucks). With former Kaiser Permanente CEO George Halvorson, I got a fascinating account of his establishing a new health system in rural Uganda. And in my in-progress interview with famed Newsweek and Vanity Fair reporter Maureen Orth, there’s a lengthy description of her two years in the Peace Corps. While perhaps not what these people are best known for, these “other projects” not only provide great insight into the individual but often offer useful insights into historical events. Sometimes you think you know the whole story, or at least the most important part of that story. But when you read — or conduct — life history interviews, you soon learn that all parts are important and those less regarded can be the most surprising.

In this spirit of uncovering less known accomplishments, I want to pay tribute to Bancroft staff who recently retired. At the end of June we witnessed the departures of Bancroft Director Elaine Tennant (also a renowned scholar of German literature and culture), Deputy Director Peter Hanff (also a recognized expert in all things Wizard of Oz, which he detailed in his oral history), finance manager Meilin Huang (also the savior of the Oral History Center on many occasions), and photographic curator Jack von Euw (also an excellent curator of many Bancroft exhibits). We bid farewell to these four esteemed colleagues. We hope that retirement adds several new and interesting chapters to already very accomplished lives.

Find these and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.

Martin Meeker, Charles B. Faulhaber Director, Oral History Center

Trial: Rock’s Backpages

Through April 5, 2021, the Library has trial access to Rock’s Backpages, the world’s biggest archive of music journalism and pop writing of the last 60 years.

Through April 5, 2021, the Library has trial access to Rock’s Backpages, the world’s biggest archive of music journalism and pop writing of the last 60 years.

Language of Music

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

Music occupies a unique position in the field of languages in that it operates as both an independent language in itself and also as an element which can be combined with spoken/written languages to create musical settings of text. In the latter case, the juxtaposition of textual language and musical language produces a more complex, multi-faceted language which embodies the meaning and expressive qualities of both of its component languages.

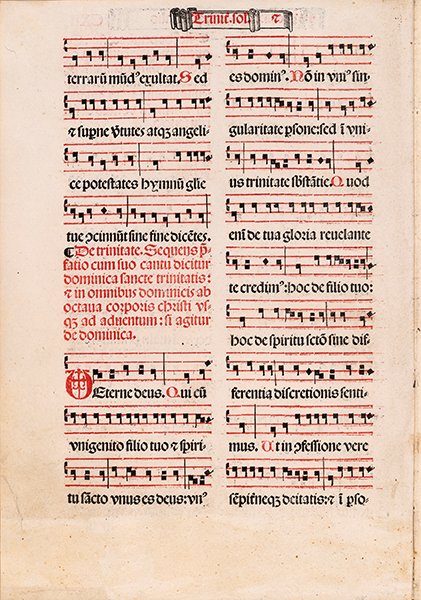

In the years BCE, music remained primarily an oral tradition, and although references to written music by some of the ancient Greek writers indicate the existence of notated music in their time, no extant examples of written music from the years BCE have been found. One of the earliest forms of Western musical notation, called Dasian notation, which first appeared in ninth century music treatises, was derived from signs used in ancient Greek prosody.[1] A system of symbols, called neumes, developed at about the same time to serve as a mnemonic tool to recall a previously memorized melody. Since most melodic tunes continued to be passed on through oral tradition at that time, neumes provided a way, albeit a limited way, to preserve existing tunes in written form. Around the beginning of the 11th century the system of neumes was expanded so that the notational symbols were written on a grid of four horizontal lines to indicate when pitches went up, down, or remained the same. Christian chant written during the late Medieval and early Renaissance periods made extensive use of this system of neumes, and the example provided in this exhibit from the Missale monasticum secundum, consuetudinem ordinis Vallisumbrose (1503) illustrates this early form of music notation. In the latter half of the 13th century, as musical notation continued to develop, the notational system expanded to indicate both pitch and the rhythmic value of pitches on a staff which, by that time, had expanded to five lines (except for chant notation, which, in most cases, continued to be written on four-line staves).

Verbal texts have been used as the basis of solo songs, vocal duets, trios and other ensembles of solo voices, as well as choral music for centuries, and it is not uncommon for a particular text to be set to music in original ways by multiple composers. Different musical settings can provide varied insights into the meaning of a text, or different interpretations of the text. Thus, music serves as a collaborative type of language which can be combined with verbal language to create an enriched, and sometimes complex, result. For example, the English bawdy song in Renaissance era was noted for presenting a text in a contrapuntal fashion in which multiple voices sang the same text, simultaneously, but at carefully paced intervals so that the words combined in different ways and created a significantly different meaning from the original text statement. The French composer Francis Poulenc was known to set well-established, serious, sacred texts to his own, personal style of music which was highly reminiscent of French dance hall music. (As an example, visit this link for a performance of Poulenc’s setting of the text Laudamus Te from his Gloria.)[2]

Of course, innumerable music works have been created that have no text component at all. Generally, this music can be divided into two categories: program music and absolute music. The former is conceived with an intended narrative association, and thus, communicates meaning as a language. Absolute music is composed without that narrative intention, but many listeners may still find meaning in this music even if it was not consciously intended by the composer. Examples of program music can be found throughout the literature from the time of the Renaissance and include such works as Andrea Gabrieli’s Battaglia, Antonio Vivaldi’s The Seasons, some of Joseph Haydn’s symphonies, and numerous tone poems from the 19th century.[3] The concept of absolute music, on the other hand, has been a topic of debate for more than a century. Many believe that certain musical works can be appreciated for their structure and design without any external associated meaning. While others believe that all music reveals (or, communicates) something about humanity, the human condition, human thought, etc. Examples of absolute music might include the Wohltemperierte Klavier of J.S. Bach, and the instrumental works of Anton Webern.[4] Numerous publications about absolute music are available for exploration.

As musical ideas have evolved, composers have changed the notation of music to accommodate ideas that could not be conveyed to the performers through traditional notational practices. The 19th and early 20th centuries brought a veritable explosion of expression markings to notated music in order to convey the composer’s expressive intentions to performers. Composers also sought new systems of musical notation to express their ideas, which often included media or performance techniques (such as “extended techniques,” electronic music notation, graphic notation, etc.) which had not been previously represented in the realm of music notation.[5] The French composer, Olivier Messiaen went so far as to invent an entire system of “translating” words and sentences into musical notation. His notation system is called langage communicable (“communicable language”). A summary of this system can be found on these two pages from the preface of his late organ cycle, Méditations sur le Mystère de la Sainte Trinité, where he introduced the system: (1) and (2).[6] In the 21st century musical notation continues to evolve and expand to accommodate the composer’s aural concepts as well as developing technologies.

The Jean Gray Hargrove Music Library at UC Berkeley provides a wealth of resource material for musicologists, music theorists, composers, performers, and other scholars in areas such as the history of music (including notation), the study of consonance and dissonance, studies in performance practice, and compositional studies of text setting, text painting, sound design, electronic music, and environmental sound. Hargrove’s special collections are world-renowned for their holdings in music primary source material dating from the early Renaissance and extending into the 20th century. Furthermore, the library’s print and media materials support studies in a wide variety of musical genres, including concert works, folk and popular music from around the world, rock music, and musical theatre. Concert music of the 20th and 21st centuries represented in the music collections include works based not only on highly organized procedures, such as those used in serialism, stochastic music, and computer-generated music, but also aleatoric and improvised music.

Contribution by Frank Ferko

Music Metadata Librarian, Jean Gray Hargrove Music Library

Source consulted:

- Grove Music Online, https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.07239, (accessed 11/19/19)

- YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ecwT4odGaZY, (accessed 11/19/19)

- YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1jD_pg-7tKY, (accessed 11/19/19)

- YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4bknpASD8c0, (accessed 11/19/19)

- “The art of visualising music,” http://davidhall.io/visualising-music-graphic-scores (accessed 11/19/19)

- http://www.robertkelleyphd.com/mespref1.jpg and http://www.robertkelleyphd.com/mespref2.jpg (accessed 11/19/19)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: “O Eterne deus” (from Missale monasticum secundum consuetudinem ordinis Vallisumbrose)

Title in English: O Eternal God

Composer: anonymous

Imprint: Venice : per Luca Antonio iuncta Florentino, 1503.

Language: Music

Source: Music Special Collections, University of California, Berkeley

Entire work: https://digicoll.lib.berkeley.edu/record/86261, See pages 254 or CXII (verso) and 256 or CXIII (recto).

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Missale mo[n]asticu[m] s[ecundu]m [con]suetudine[m] ordinis Vallisumbrose. Venetiis : per … Luca[m]antoniu[m] de giu[n]ta Flore[n]tinu[m], 1503. Music Case X. M2148.1.M5 V4 1503

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

![The Languages of Berkeley [fan]](https://update.lib.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/fan_languages-450px.jpg)