Tag: environmental history

Growth and (Re)connection: My Experience with the Save Mount Diablo Oral History Project

Anjali George is a junior at UC Berkeley majoring in Sociology. She enjoys reading, dancing and being in nature. She was an Undergraduate Research Apprentice Program intern with the Oral History Center in spring 2022, during which time she worked on a podcast for the Save Mount Diablo Oral History Project.

When I joined the Save Mount Diablo Oral History Project offered through The Oral History Center’s Berkeley Remix podcast, I really did not have any idea what I was doing—I had no experience in oral history, very little knowledge of Save Mount Diablo and no understanding of podcasts beyond the fact that I enjoy listening to them. Yet, I knew immediately that this was something I deeply wanted to do. Despite my lack of experience, I have always been fascinated by the practice of oral history and the importance of documenting and sharing history in a way that is accessible to the public. From what little I knew of Save Mount Diablo at the time (a land trust and conservation organization in the East Bay), I felt drawn to its mission and values, and I knew I wanted to be part of this effort to celebrate and preserve its history through the podcast.

As I worked through the Save Mount Diablo interviews that had been compiled for this oral history project, I learned so much more about the organization and environmental conservation in general, as well as about myself and my own relationship with the environment. I think what I initially found compelling about the organization was its focus on fostering education and community in order to sustain its more physical goals, like fundraising and land conservation. Ted Clement, who has been Save Mount Diablo’s executive director since 2015, had so many insightful thoughts and experiences that he shared in his interview. Hearing him speak about how the climate crisis, at its core, is “a materialization of our very poor relationship with nature,” very clearly put the organization’s education branch into perspective. Ted explained that the widespread disconnect between people and nature calls for an entire cultural realignment, which is where education comes into play. After stepping into his role in the organization, Ted immediately prioritized education as a primary goal, so that the broader community can start to transform its cultural values and develop a healthier, more meaningful relationship with nature. He spoke of earth-centered cultures, in which nature is considered sacred, placed “at the center of the value system.” Listening to Ted’s interview, it became clear that Save Mount Diablo is more than just a land trust and conservation organization—its efforts to spread awareness and educate the public, coupled with its desire to connect people to nature and to one another, make its work so much more impactful in creating sustainable change.

Even with my lack of oral history experience prior to this project, I have always found it so crucial to understand history in general, not only to learn from the past, but also to preserve it. And in that sense, I have a deep admiration for the practice of oral history and the way it preserves and passes along different histories, especially regarding topics and perspectives that often get overshadowed or overlooked. Working with Ted’s interview—as well as all of the other interviews that had been conducted—really reinforced the importance of oral history for me, in the sense that hearing the history from those who actually experienced it adds so much more depth and understanding to the story. On the more technical side, I hadn’t previously understood the complexities of creating a podcast—or more broadly, even taking primary sources and turning them into a developed, cohesive story. By listening to the interviews and reading through the transcripts, I quickly began to recognize what pieces of information were important to get across to the audience. From there, I learned how to develop a narrative that conveys the relevant information while also speaking to the audience and making them care about the story. Even the thought process that goes into crafting a compelling story—drawing on charismatic speakers, finding quotes that are both significant to the story and also entertaining to hear, summarizing information that might be too dense or nuanced for an audience to bother sitting through—there are so many small details to take into consideration to be able to turn those initial interviews into a finished product.

I learned so much more than I could have expected from working on this project—about working with primary sources and creating a story, about environmental conservation, about myself and how I want to move through this world—and I’ll continue to carry this experience with me and apply it in other aspects of my life and my learning. I’ve learned how to look at any given information and pull out the important themes, how to string different stories together to paint a broader picture, how to think about what appeals to an audience and how to make them care. Even outside of a storytelling framework, these skills easily transfer over to different parts of my life, from critically analyzing academic content to carrying conversations in my daily life. Moreso, hearing Save Mount Diablo’s history and accomplishments, even hearing how its relationship with nature and conservation efforts has changed over the years, has genuinely inspired me to rethink my own relationship with nature and what I can do in my own life to reconnect with the natural world around me. In this tumultuous time, with the pandemic and the increasing severity of the climate crisis, I think it is very easy for people to feel hopeless or to feel like the damage done is irreversible. However, I believe documenting Save Mount Diablo’s history and its accomplishments is an important reminder that there are people on the ground putting in the effort, doing the work that needs to be done, creating change and making a real impact on the climate crisis. I think this podcast can be not only a celebration of Save Mount Diablo’s work, but also a source of hope and motivation for the listening audience to persevere and to keep doing our part—no matter how big or small—and I am beyond grateful for the opportunity to have taken part in this project.

Find the interview mentioned here and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.

Preserving Spaces and Stories with Save Mount Diablo

by Samantha Ready

Samantha Ready is an Undergraduate Research Apprentice at the Oral History Center. She worked with Shanna Farrell and Amanda Tewes during the Spring ’21 semester to help them prepare for their upcoming oral history project celebrating Save Mount Diablo’s 50th anniversary.

From Samantha: My name is Samantha Ready (she/her) and I’m from Little Rock, Arkansas. I am currently a third-year at Cal double majoring in Ethnic Studies and Geography with a minor in Race and the Law. Some of my favorite pastimes are hiking, traveling, and listening to Johnny Cash.

This semester, I had the privilege of joining the Oral History Center’s Save Mount Diablo Project as a background researcher under the mentorship of Shanna Farrell and Amanda Tewes. Despite growing up in the ‘Natural State’ of Arkansas, I didn’t learn much about environmental preservation. Coming into this research project, my personal definition of preservation was limited to the scope of society and culture. I’ve focused my studies on supporting and amplifying the perspective of marginalized communities, because they are often overshadowed by dominating narratives. Working on this project taught me about two important things that were missing from my definition of cultural preservation: land conservation and oral histories. Because I learned about the deeply rooted connections between environmental preservation and personal narratives, I now see clearly how important these facets are to the preservation of cultures and histories from all voices.

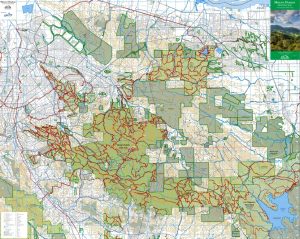

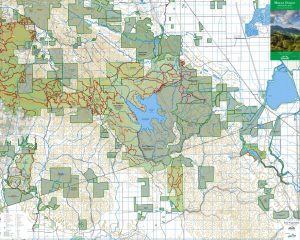

Save Mount Diablo (SMD) is a nationally accredited land trust organization and has been working to conserve the land around Mount Diablo in the East Bay since 1971. The preservation of natural land is a main goal of SMD, and has thus far been achieved through consistent advocacy, dedicated stewardship, thoughtful land-use planning, and educational programs. Mount Diablo’s biodiversity, historical and agricultural significance, and natural beauty are important to both the area’s general quality of life and natural resources. SMD works to provide ways for people to interact with the environment at Mount Diablo through recreational opportunities that consistently protect the region’s natural resources and open spaces, such as their Discover Diablo public hiking program, educational classes with local schools, and the annual Four Days Diablo backpacking trip through the mountain. Below are two maps of 2020 The Mount Diablo Regional Trail Map, which both feature the Diablo Trail that spans across the entire regional area. Of the 338,000 total acres shown between both maps, more than 120,000 acres have been preserved and protected thanks to Save Mount Diablo. Seth Adams, SMD’s Land Conservation Director, says that “No other map shows all of the Diablo area parks in a unified design and in regional context. The map illustrates what has been accomplished and what private lands still need to be protected.” (SMD website) The first map features Mount Diablo State Park and surrounding parks, and the second features Los Vaqueros and surrounding parks.

Mount Diablo & Surrounding Parks:

Los Vaqueros & Surrounding Parks:

Image Credits: maps produced by Save Mount Diablo

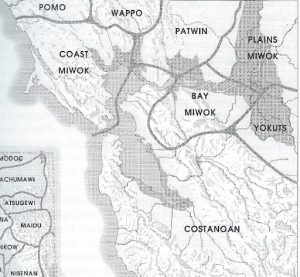

In my research about Save Mount Diablo, it became apparent that working alongside surrounding community members -including SMD membershipSMD membership, various outside organizations, and political leaders/institutions- has been vital to maintaining their mission of preserving the environment. My first point of interest here was learning more about which communities and organizations SMD has worked with, how, and why. I immediately thought of Indigenous communities connected with Mount Diablo. Bev Ortiz, a Native American historian and SMD newsletter contributing author, wrote an article entitled “Mount Diablo as Myth and Reality: An Indian History Convoluted,“ in which she describes the mountain’s cultural and religious significance to Native Nations. Mount Diablo is meaningful for the Nations of the Miwok, Maidu (Nisenan), Ohlone (Chochenyo), Pomo, and Wintun Nations. Ortiz connected with members from these Native Nations in her work of preserving their cultural connections with Mount Diablo, from whom she learned about these connections, which included creation stories of several Nations. Creation stories are the original forms of oral history, and have helped preserve Indigenous cultures for thousands of years. Below is a map by Mount Diablo State Park of languages spoken by Native Americans from the region of Mount Diablo.

Image Credit: Mount Diablo State Park

Save Mount Diablo has often recognized Native cultural connections with Mount Diablo throughout its efforts to protect the mountain, such as in SMD Director of Land Programs Seth Adams’ timeline of the History of Mount Diablo, SMD’s stance to protect Tesla Park, and SMD Executive Director Ted Clement’s event to discuss SMD’s work with Indigenous communities to preserve cultural resources. Native American culture strongly connects with the environment, as they were the Earth’s first caretakers and the first to sustainably manage the world’s natural resources. Indigenous Nations around the world have maintained that stewardship of their ancestral homelands would be the first step to restoring their relationship with the land after colonization. In this sense, the inclusion of Native communities in environmental preservation would also aid in the preservation of their culture(s). To me, Save Mount Diablo’s work with Native communities thus far indicates their sincere recognition of how important the preservation of Native connections with Mount Diablo are to preserving the region’s land. Though there is definitely recognition, I remain curious as to the extent Indigenous communities are directly involved in SMD’s stewardship and conservation of Mount Diablo lands.

Another part of the community Save Mount Diablo works within is the political sphere. SMD has been heavily involved in, or at least taken stances on, several ballot measures throughout its50 years of fighting for environmental preservation. SMD also spends a lot of time tracking proposals by potential developers to ensure they follow the environmental rules and protections set by the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) of 1970. The main purpose of CEQA is to prevent and decrease environmental damage by developments and to allow a public decision-making process, which enables community members to discuss their concerns regarding development projects’s environmental effects. This work has led to SMD’s working with local political leaders and alliances with conservation networks in order to defend Urban Limit Lines (ULLs) against developers of preserved space in the Mount Diablo region. These ULLs preserve and protect open spaces, and are often threatened by developers, corporations, and some politicians. In their encouragement of public engagement with these issues, SMD provides email templates to send to local and state political leaders about issues at hand. Save Mount Diablo has been successful in these political methods of environmental preservation largely due to their active involvement and communication with outside persons, organizations, and institutions. Through its years of interactions with political representatives, public organizations, and parks districts, I wonder how, if at all, SMD’s standing as a private organization has affected the outcomes of these interactions. Additionally, I’m curious about how situational outside influences affected these interactions.

Image Credit: EnvironmentalScience.org

When learning about stories of the past, even those of organizations like Save Mount Diablo, it’s important to think about the perspective from which the story is being told. Learning about oral history played a big role in helping me realize that because of its practice to amplify and preserve individual voices so as to learn about their personal and lived experiences of historical occurrences. UC Berkeley’s Oral History Center (OHC) continues this mission across a variety of projects, including in this Save Mount Diablo Project. An ultimate goal of the SMD oral histories is to understand how the organization promotes a thoughtful relationship between people and the environment to inspire positive growth for the natural land and society as a whole. The background research I was able to contribute this semester barely scratched the surface of this story, and the rest lies in the stories soon to be told in the oral histories of Save Mount Diablo.

Learning about notable contributions of Save Mount Diablo to land conservation and environmental preservation taught me about how intersectional preservation is with most, if not all, facets of life. Not only do they work to conserve land that is sacred both biologically and culturally, SMD consistently provides recreational and educational resources for teaching and learning about the environment and the importance of preserving it. Now, it’s time for the preservation of Save Mount Diablo’s stories.

One Shot for Gold: Developing a Modern Mine in Northern California

by OHC Emeritus Historian/Interview Eleanor Herz Swent

An account of the creation of a modern, environmentally sensitive mine as told by the people who developed and worked it, from the University of Nevada Press Spring 2021 catalog.

In connection with this, Swent will be presenting her work as part of the American Society for Environmental History’s Environmental History Week. Her panel will be on Earth Day, and more information can be found here.

……………………………………………………………………………………..

As this was written, the Mars Rover Perseverance landed, thanks in part to research conducted at the mine in Napa County that was the subject of this book.

This is a different kind of oral history – not the life of a person, but of a mine – California’s most productive gold mine of the twentieth century. Between 1985 and 2002, the mine produced about 3.4 million ounces of gold, transforming the state’s poorest county and changing the industry around the world. OHC’s Knoxville/McLaughlin project, the basis for this book, comprised forty-eight interviews conducted over ten years.

In 1965, James William Wilder had a successful earth-moving and hauling business and decided to try mining. His research led him to buy the Manhattan mercury mine in the Knoxville District of Napa County. “We called it One Shot. If we don’t make it on this one, we’re out of the mining business.”

In 1974, Willa Baum, director of what is now the Oral History Center, was advisor for an Oakland neighborhood history project endowed by the NIH, and Eleanor “Lee” Swent was a volunteer, interviewing residents of the Fruitvale district and Chinatown. When Willa learned that Lee had spent most of her life living in mining towns, and that both her father and husband were mining engineers, it seemed that the time had finally come to document one of the most important aspects of California history – mining. In 1986, with the support of the American Institute of Mining, Metallurgical, and Petroleum Engineers [AIME], the Mining Society of America [MSA], and the Woman’s Auxiliary to the AIME [WAAIME], the oral history series on Western Mining was established, and from then until 2001, Lee conducted 46 full-length oral histories with significant figures in the industry. They were men, with three exceptions: Helen Henshaw, the wife of the president of Homestake Mining Company; Catherine Campbell, geologist, editor, and widow of Ian Campbell, California State Geologist and Director of the California Division of Mines and Geology; and Marian Lane, aka Winnie Ruth Judd, wife of a mine doctor.

In 1978, a young geologist working for Homestake Mining Company, California’s oldest corporation, explored the One Shot mercury mine. “It was just a joy to look at. It has to be one of the best exposed, zoned gold deposits that ever was. It was just a type example of the mercury-hot-springs-gold association; a classic example.”

It was accessible only from Lake County, at that time, the poorest in the state, with a median household income of $5,266 and a population of 19, 548. By 1989, when the gold mine was in production, the income had about quadrupled, to $21,794, and in 1990 the population was 50,631. With funding support from Homestake, a community college branch was subsidized to train local workers, a hospital expanded its services, telephone and electric utility service was extended, and roads were paved. Many of these improvements were lasting benefits to the county.

The life of the mine was projected to be about twenty years, and most of the key players were available for interviews. It was a rare opportunity to document the discovery, development, and reclamation of a mine while it was happening. In 1991, the Knoxville District/McLaughlin Mine oral history project was launched.

Between then and 2005, forty-eight interviews, from two to seventeen hours long, were conducted with the owner of the One Shot Mine; Homestake officials and a wide range of employees; supervisors and planners from Napa, Lake, and Yolo counties; the Lake County school superintendent, local historians, mercury miners, merchants, and ranchers, as well as some of the most vocal opponents of the mine. Their voices help to tell the story of the mine and a changed community.

An engineer from New Zealand was manager for the construction. “This was the biggest nonunion construction project that had ever been done in California. It was thirty-odd miles long and we did 3 million man-hours. We engineered the dickens out of everything.” A rancher’s wife appreciated her job as a mine surveyor. ”I’ve learned invaluable stuff on the computers that I had never had any experience with before.”

“One Shot for Gold” documents the effort to win public support and to obtain an unprecedented number of 327 permits from the federal, state, regional, and local agencies that had jurisdiction. Homestake engineers tell of their research from Finland to South Africa to develop the method of high-pressure oxidation to recover gold from ore without polluting air or water; it has now been copied around the world.

The mine was named for Donald Hamilton McLaughlin, chairman emeritus of Homestake and a regent of the University of California. In 1961, his wife, Sylvia Cranmer McLaughlin, founded Save San Francisco Bay, one of the first grassroots environmental organizations, that sparked national awareness and led to the first Earth Day, celebrated in San Francisco in 1974. This movement forced Homestake to incorporate environmental protection into its business model. From the beginning, plans for the mine included reclamation as the Donald and Sylvia Nature Reserve, part of the University of California Natural Reserve System. He died at the age of 93 on December 31, 1984, and Sylvia McLaughlin dedicated the mine to him in a ceremony on Saturday, September 28, 1985. The natural reserve named for them is a fitting coda to the story of a modern mine: extracting one precious resource, gold, and preserving another, the natural environment, its air and water.

In 2001, the mine geologist recalled, “NASA Ames research showed up at the door to look at samples of rock from our hot springs terraces that contained fossilized bacterial remains, evidence for the most primitive live on earth, to think through how landers on Mars would go about sampling and looking for evidence of life.”

“One Shot for Gold” begins with the mercury mine at Knoxville and ends with the Donald and Sylvia McLaughlin Nature Reserve. On February 11, 2021, the director of the reserve wrote, “Since around 2010, we’ve had a team from NASA and biogeochemists from various universities working on understanding the bacteria that live in geologic water deep inside serpentine rock, and how those studies can inform exobiologists where to look for life on other celestial bodies.”

As this was written, the astrobiology Rover Perseverance landed on Mars, ready to hunt for signs of life like those preserved at the depths of the Mclaughlin mine.

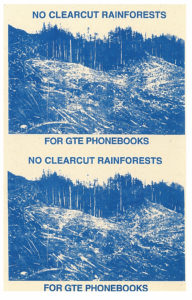

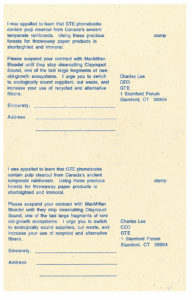

Additions to the Rainforest Action Network Records Now Open at The Bancroft Library

At first I thought I was fighting to save the rubber trees;

then I thought I was fighting to save the Amazon rainforest.

Now I realize I am fighting for humanity.

– Chico Mendes (1944-1988)

The Bancroft Library is pleased to announce that a series of additions to the ongoing Rainforest Action Network records is now open and accessible to researchers. The processing of the Rainforest Action Network records is part of a two-year grant project funded by the National Historical Publications and Records Commission to make available a range of archival collections relating to environmental movements in the West. A leading resource in the documentation of U.S. environmental movements, The Bancroft Library is home to the records of many significant environmental organizations and the papers of a range of environmental activists.

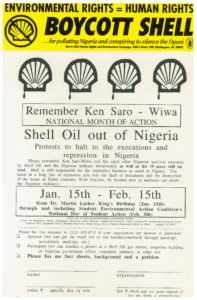

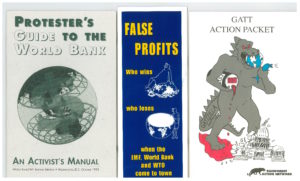

Rainforest Action Network was founded in 1985 by Randy “Hurricane” Hayes and Mike Roselle as a San Francisco based non-profit grassroots environmental group with a mission to protect and preserve the world’s forests and defend the human rights of indigenous people and others affected by unjust land grabs and the depletion of natural resources. Rainforest Action Network’s direct action, education and marketing campaigns apply pressure to governments and corporations to halt illegal logging, manufacturing, selling and use of old growth trees and tropical forests.

The global breadth of Rainforest Action Network’s activities range from Old Growth campaigns in Northern California, the Pacific Northwest and Canada to Tropical Timber campaigns to protect forests and indigenous rights in Central and South America, Africa, Tasmania and Southeast Asia. They also include the Global Finance campaign which organized and supported civil disobedience during the World Trade Organization meetings in Seattle, Washington in 1999.

The Bancroft Library has been collecting Rainforest Action Network records since 2006 and the newly opened additions document the group’s campaigns primarily in the 1990s-2000s. Future additions to the records are expected.

Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea: This is Not a Fish Story , This is a Fish Story

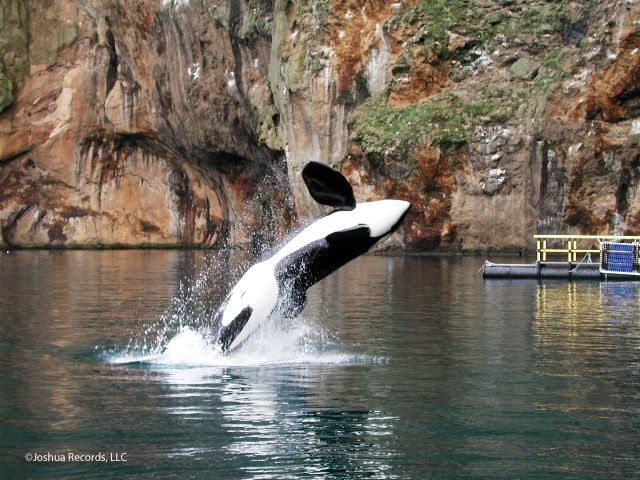

What would it be like to fly halfway around the world on a non-stop flight from Newport, Oregon to Vestmannaeyjar, Iceland aboard a C-17 Air Force transport plane with a small crew of environmentalists, veterinarians, and an internationally famous 21-foot long, 10,000 lb. orca “killer whale”?

Detailed answers to that question and much, much more can be found in the Earth Island Institute records, a newly processed collection now open to researchers at The Bancroft Library.

Earth Island Institute is a Berkeley based non-profit conservation group founded in 1982 by David Brower that acts as an incubator to support a global network of ecological and social justice projects working to conserve, protect and restore the environment. Born in 1912, Brower entered the University of California at Berkeley at age 16 with a plan to study entomology, but due to financial pressures had to leave school by his sophomore year.

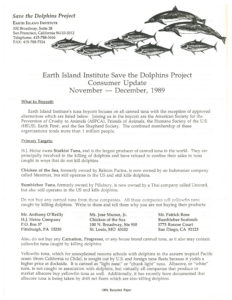

Located in the David Brower Center in downtown Berkeley, you may have walked by or visited the LEED Platinum rated building, read the Earth Island Journal publication, or be familiar with Earth Island’s work going back to the late 1980s on the dolphin-safe tuna campaigns. Those campaigns helped to heighten awareness of dolphin by-catch mortality levels during purse seine net and drift net fishing practices for tuna fish, reform marine mammal protection laws and establish the dolphin-safe tuna labels.

One of Earth Island’s other major projects began in 1994 after the film Free Willy was released by Warner Bros. and brought worldwide attention to the plight of captive marine mammals everywhere, although especially for the orca “killer whale” known as Keiko who starred as Willy. First captured off Iceland in 1979, Keiko was owned by Reino Adventura, a theme park in Mexico City, Mexico during the film’s production. After Earth Island Institute, numerous animal welfare groups, environmentalists and children from around the world rallied to free Keiko, Reino Adventura agreed to donate him to the newly formed “Free Willy Keiko Foundation” for a program of rehabilitation at the Oregon Coast Aquarium in Newport for eventual release back to the wild.

What happened to Keiko from then on is now in the historical record and up for research and debate. Although Keiko was released back into the wild, first into the Iceland sea pens in September 1998 and then into Iceland’s open waters, he died off the coast of Norway in December 2003 from pneumonia and possibly hunger, having lost the ability to fish for himself after being held captive so many decades. Since 1961, hundreds of killer whales, or orcas (actually a type of dolphin) have been captured and used in theme parks to entertain, and some would argue to educate, the public on the beauty and wonder of these magnificent beings.

As of 2018, there are approximately 60 captive orcas and countless dolphins and other marine mammals being held and used for entertainment at theme parks primarily in China, France, Japan, Russia, Spain and the United States. And yet, captive orcas are certainly not the only killer whales in harm’s way. As evidenced in a number of recent studies, films and news stories – orca populations in the wild are dwindling at rapid rates as declining fish stocks, marine pollution and other factors like increased shipping traffic have caused them to be at extreme risk for extinction. The time to learn about orcas, marine mammals, the greater ecosystem of our world environment and how we can improve life for all creatures of the land, air and sea is now!

The processing of the Earth Island Institute records is part of a two-year NHPRC-funded project to process a range of archival collections relating to environmental movements in the West. A leading repository in documenting U.S. environmental movements, The Bancroft Library is home to the records of many significant environmental organizations and the papers of a range of environmental activists.

Environmental Justice Grit in the Borderlands

Environmentalists make terrible neighbors, but great ancestors. – David Brower

It would be difficult not to notice a common thread of diligent, dogged persistence across the broad spectrum of environmental justice activism. This tenacity, coupled with a long view of the world and a whole lot of hard work, is what makes for some of the most successful environmental justice campaigns.

While success cannot be measured in one brief moment or win where environmental issues are concerned, each victory adds to the larger picture of global environmental awareness and health of the planet. Multiple stories of such environmental justice grit can be found in the collections at The Bancroft Library and one collection in particular is the newly opened records of Arizona Toxics Information.

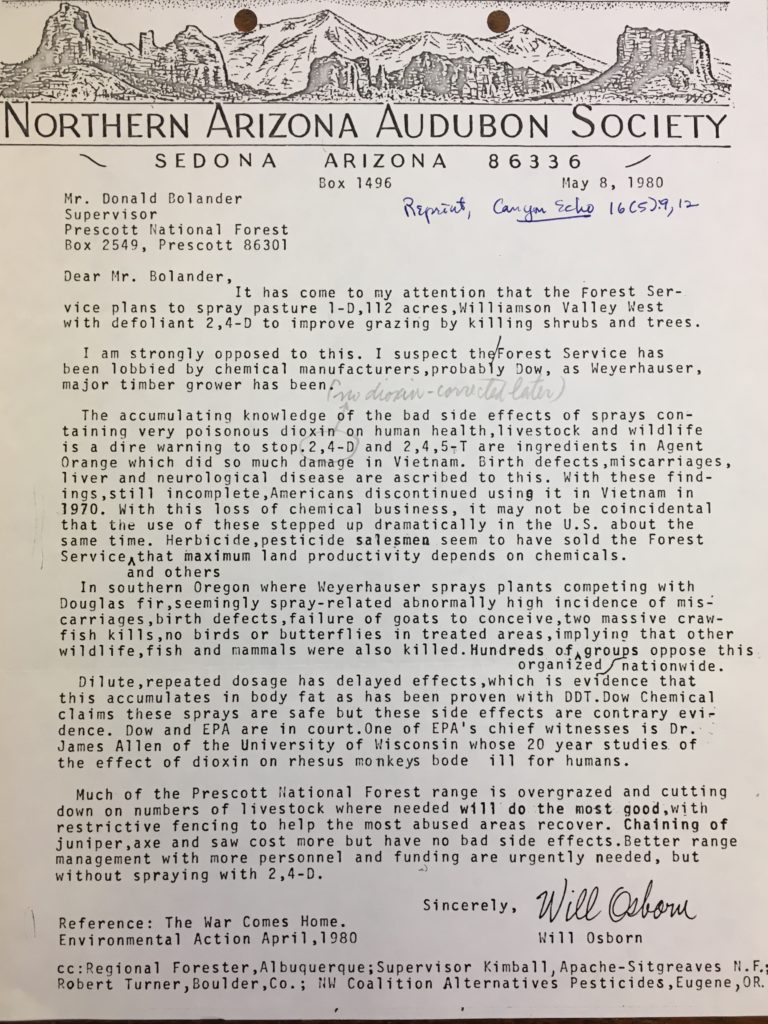

Focused primarily on environmental concerns in the Arizona/Mexico border region during the 1970s through 1990s, Arizona Toxics Information was founded by conservationist Michael Gregory in 1990. The collection also includes materials collected by Gregory before Arizona Toxics Information was established when he worked with the Sierra Club Grand Canyon Chapter and grassroots environmental groups. Gregory had been employed by the United States Forest Service in the early 1970s and had witnessed the spraying of herbicide 2,4,5-T in national forests while he was stationed at fire outlook towers. 2,4,5-T is one of the main components of Agent Orange, which had already been banned for use in Vietnam due to its known harmful health effects and birth defects. From there, Gregory set about to research, collect information, write articles and lobby to end the practice of herbicide, pesticide and insecticide spraying in national forests and range lands.

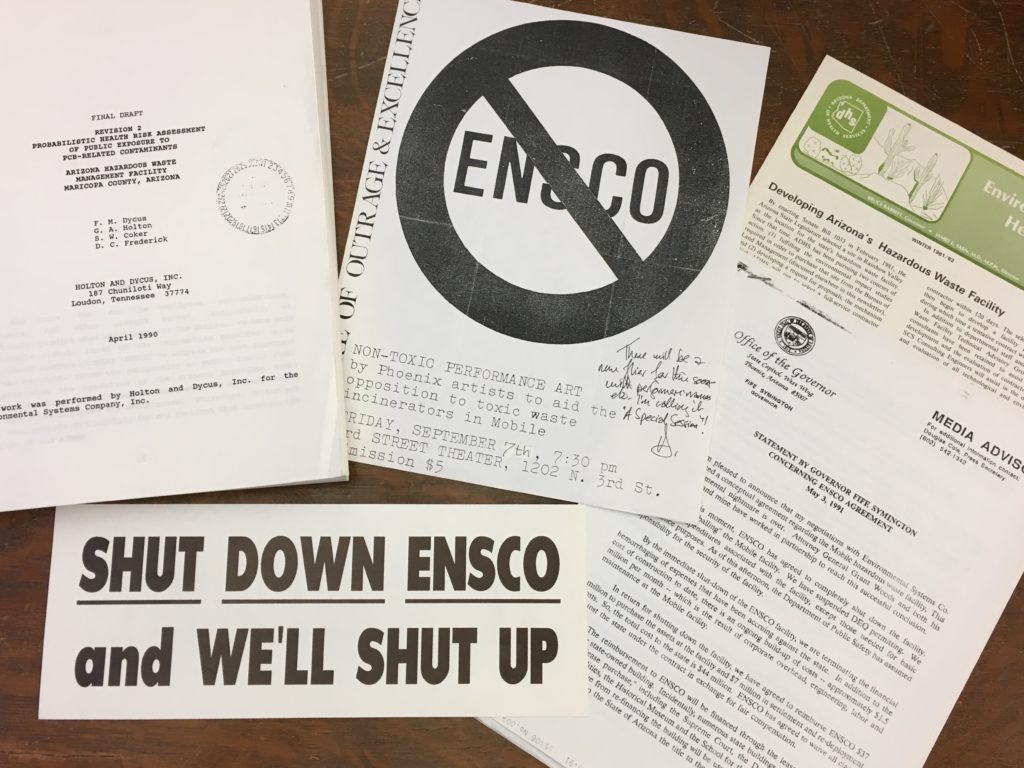

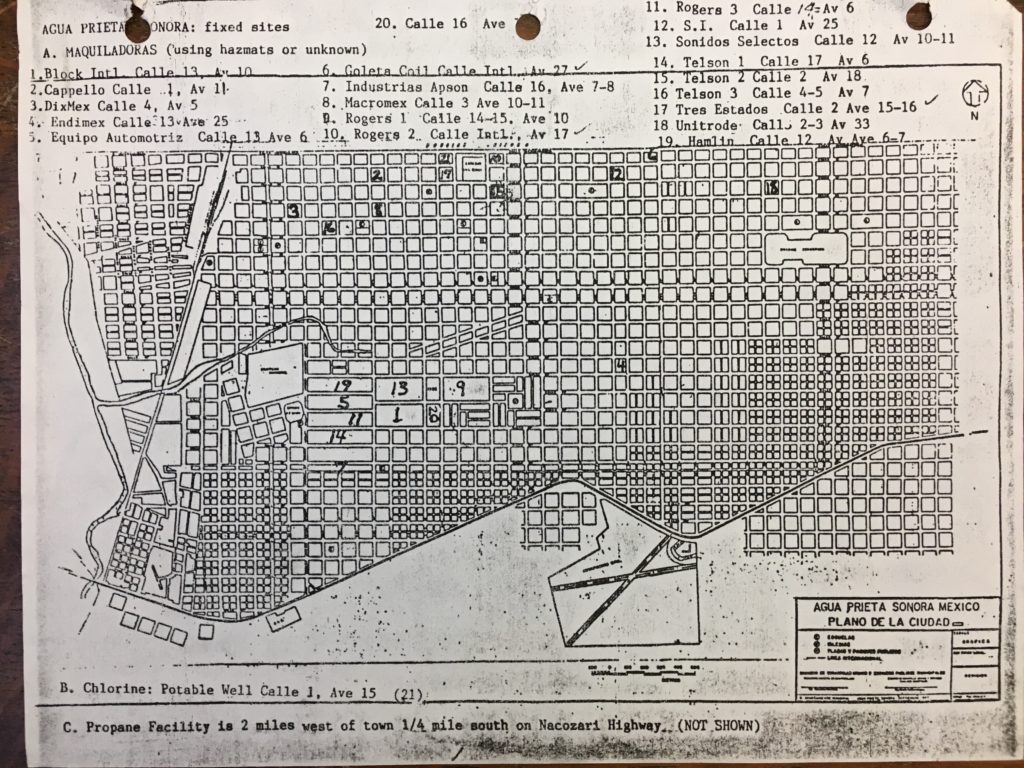

In addition to the fight for pesticide use awareness and regulations, Arizona Toxics also ran several successful campaigns to shut down the Phelps-Dodge Corporation’s Douglas Reduction Works (copper smelter), the ENSCO hazardous waste management facility (PCB incinerator), and to improve the overall air and water quality of Arizona. As the Environmental Protection Agency’s Integrated Environmental Plan for the U.S.-Mexico Border Area and the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) were being drafted in the early 1990s, Arizona Toxics Information lobbied and organized grassroots groups on both sides of the border to share information and rally for a multitude of environmental commitments in the agreements. These commitments included providing the public the “right-to-know” about pollutants being released from factories on both sides of the United States-Mexico border, regulating maquiladoras (factories in Mexico that are generally owned and operated by foreign companies which assemble products often to be exported back to the country of that company), and developing emergency disaster plans to respond to hazardous waste accidents.

The current status of NAFTA casts some doubt on the future of these agreements. The opening of the records of Arizona Toxics Information provides timely documentation of hard-won environmental justice victories on the US-Mexico border.

The processing of the Arizona Toxics Information records is part of a two-year NHPRC-funded project to process a range of archival collections relating to environmental movements in the West. A leading repository in documenting U.S. environmental movements, The Bancroft Library is home to the records of many significant environmental organizations and the papers of a range of environmental activists.