Pictorial Collections

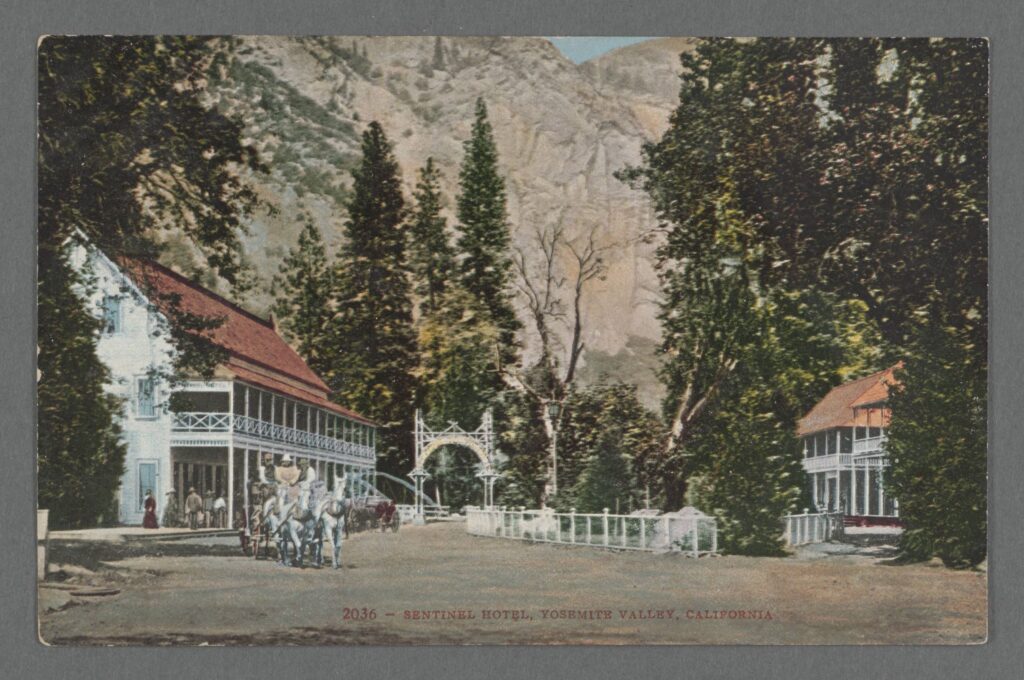

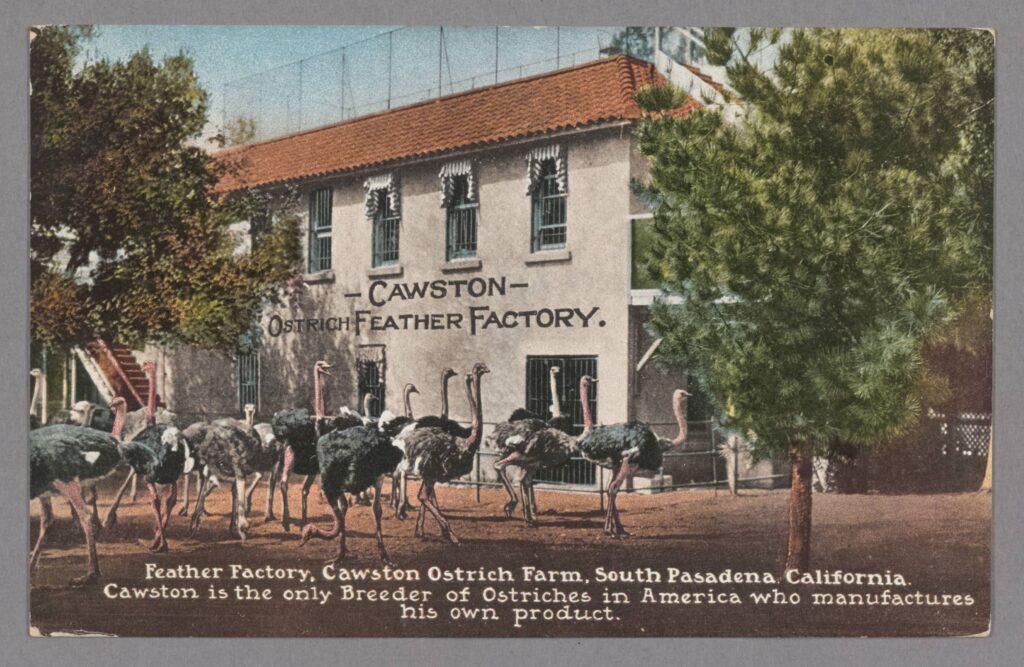

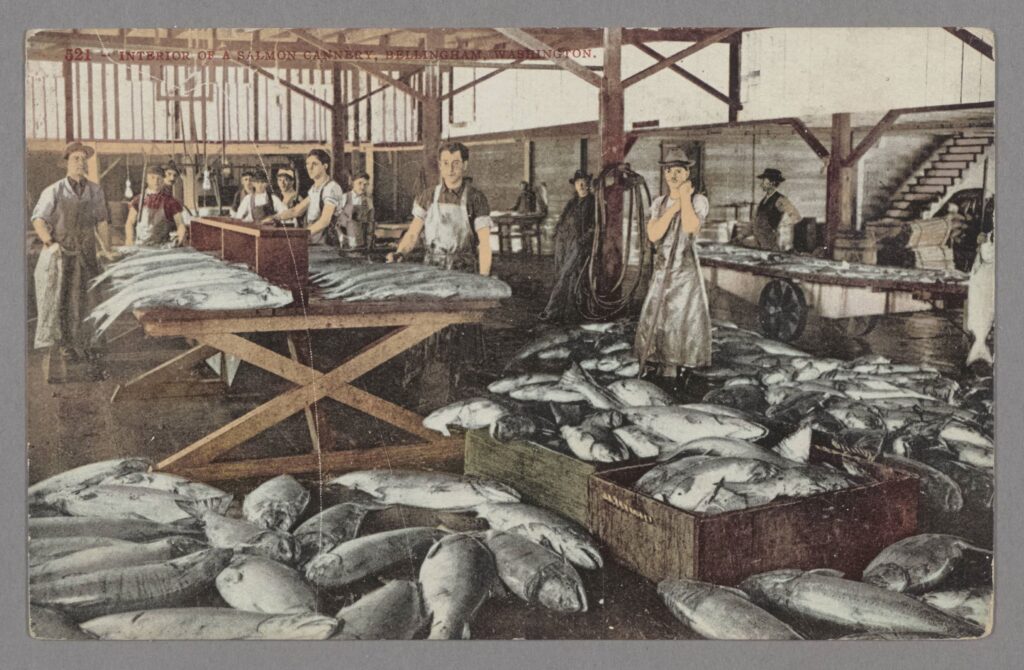

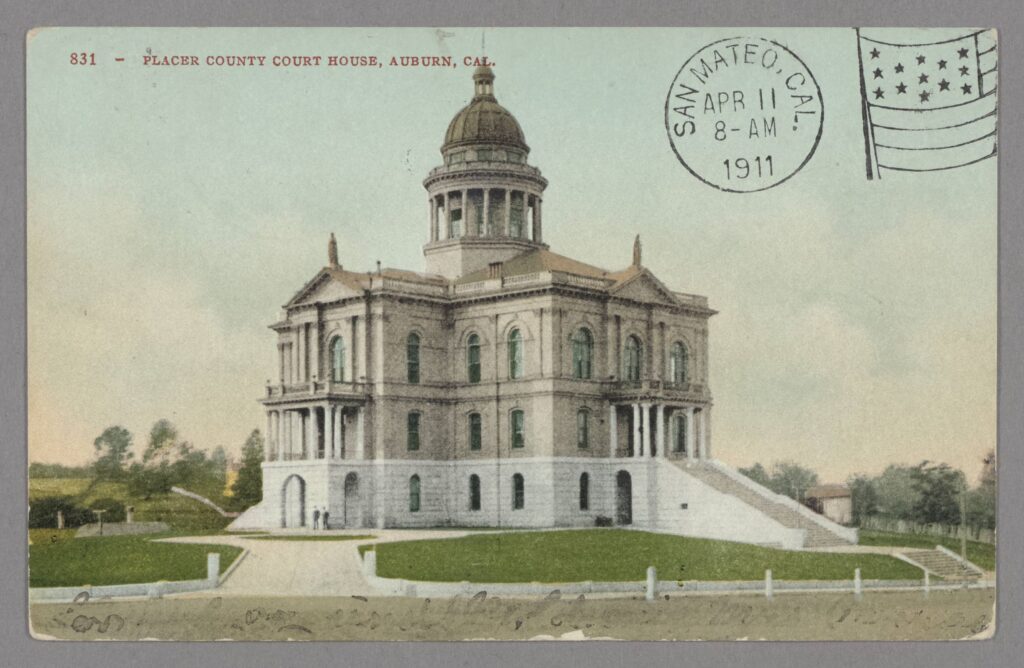

Scenic Views, Civic Pride, and Silly Gags: Edward H. Mitchell Postcards at The Bancroft Library

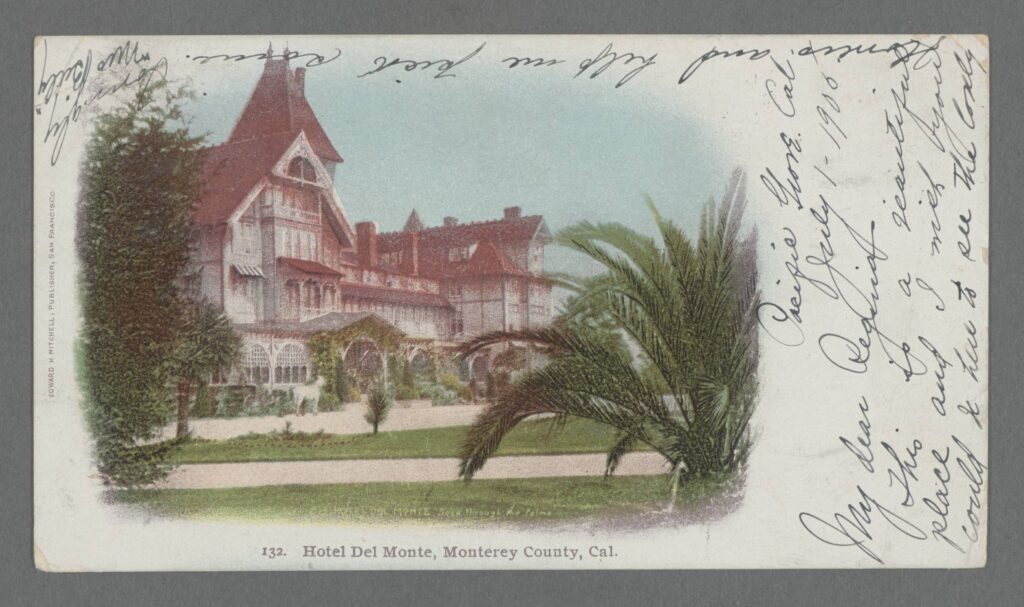

We all feel our wings are clipped this holiday season, but you can enjoy a tour around turn-of-the-century California, journey up the Pacific Coast, around the American West, or even visit Hawaii and the Philippines, thanks to newly published content on the Berkeley Library’s Digital Collections site.

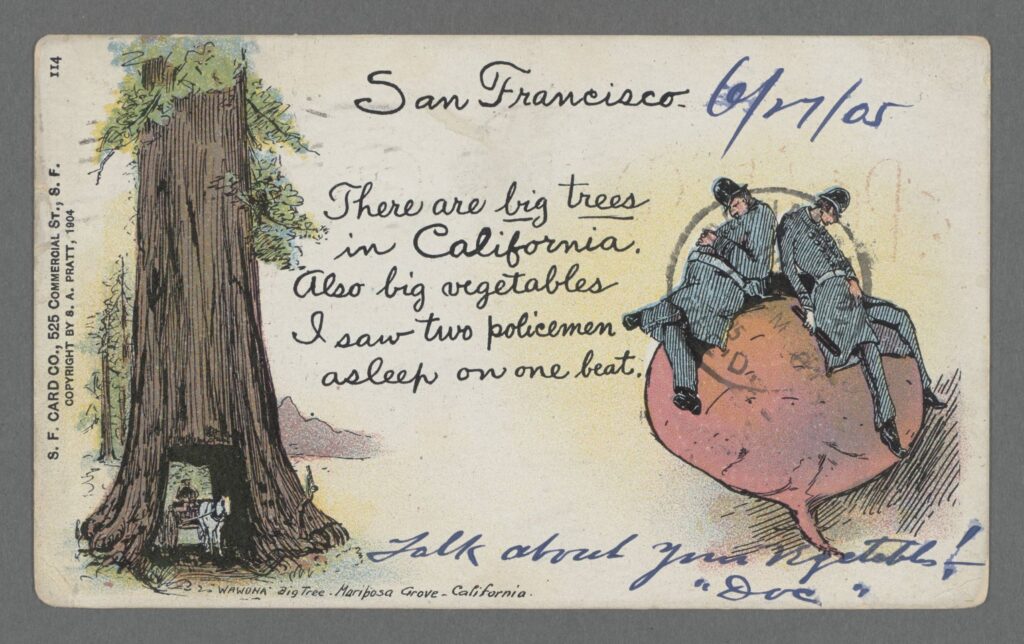

Over 10,000 postcards issued by San Francisco publisher Edward H. Mitchell, circa 1898-1920, are now online. This nearly-comprehensive collection was compiled over many decades by Walt Kransky, who generously donated it to The Bancroft Library. Walt’s website has been the go-to site for collectors interested in Mitchell cards; there he compiled a checklist of all known Mitchell postcards, whether he owned examples or not. And he did own the vast majority!

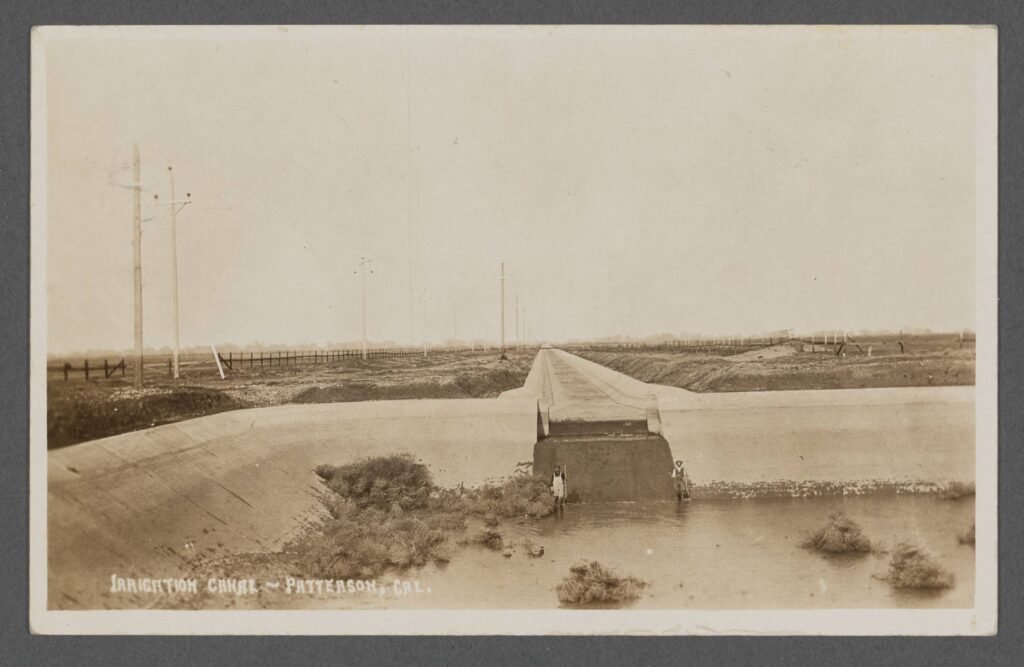

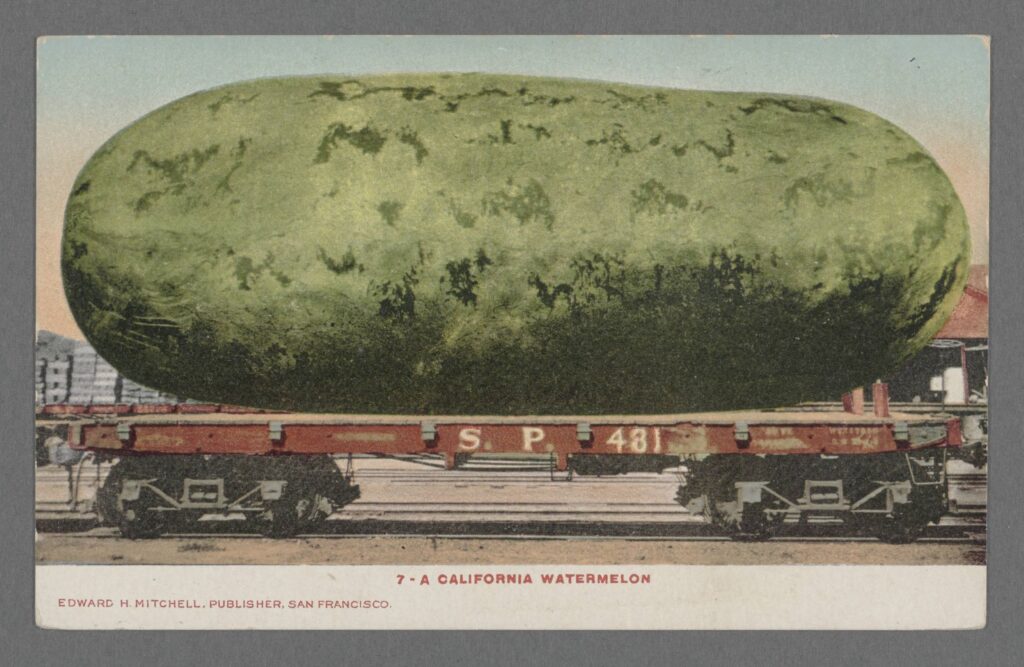

Must-see tourist sites from Yosemite to Southern California beaches and the mountains and forests of the Northwest are in abundance, but so are local industries, agriculture, and countless examples of small town pride.

There is quite a range of court houses, schools, asylums, and even irrigation works on view.

Period humor, for better or worse, is a recurring feature.

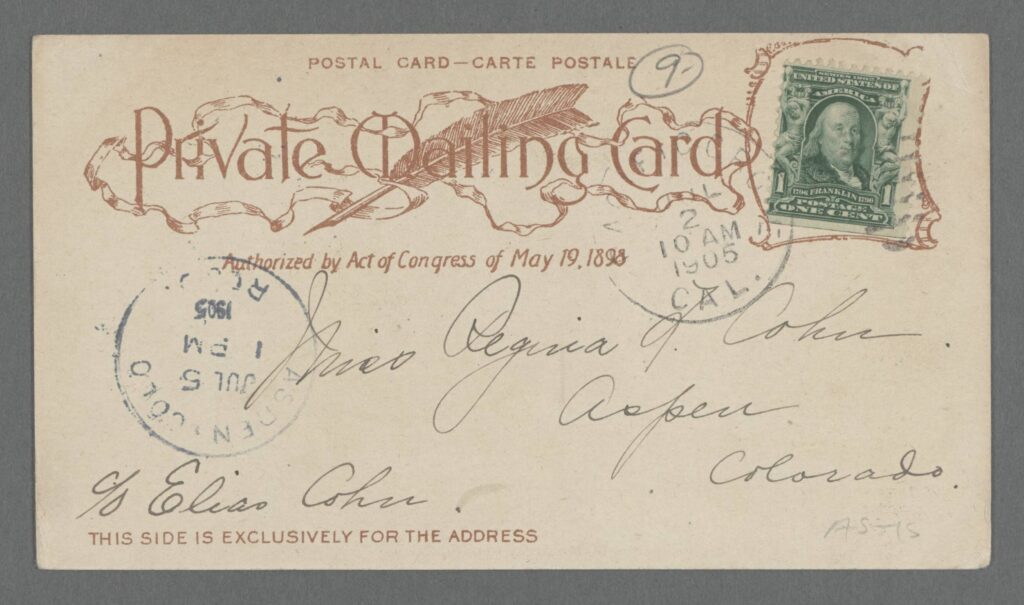

In addition to great images, Kransky’s Mitchell collection provides insight into the business of early postcard production. This was a new form when 1898 “Private Mailing Cards” were first issued as “authorized by act of Congress.”

Walt Kransky arranged his collection by back type and imprint style and he collected duplicates of given images in all their various styles of presentation. This variety, all from a single publisher, offers great opportunity for scholarship and close studies of visual culture early in the 20th century.

So, whatever your interest, make a cup of cocoa and enjoy an armchair tour, courtesy the Walter Robert and Gail Lynn Kransky collection of Edward H. Mitchell postcards at The Bancroft Library!

Many Library staff collaborated to bring this collection online. Bancroft curatorial and acquisitions staff worked with the donor to preserve this collection at Berkeley, and hundreds of hours of work on descriptive data and inventory alignment were carried out in Bancroft Technical Services’ Pictorial Unit. Library Imaging Services created the thousands of high resolution scans, and the descriptions and images were linked together and brought online through the efforts of Library IT. Most importantly, thanks are due to Walt and Gail Kransky for their generosity, his decades of collecting, and the years of expertise he committed to documenting his collection.

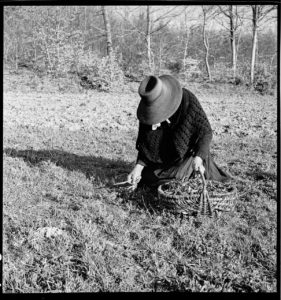

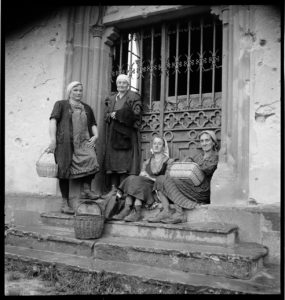

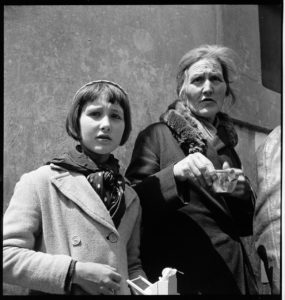

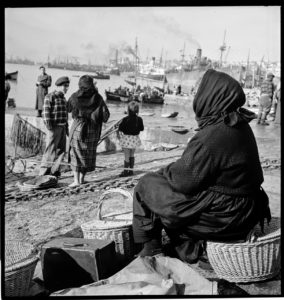

Wrapping up Women’s History Month: Selections from the Thérèse Bonney photograph collection at The Bancroft Library

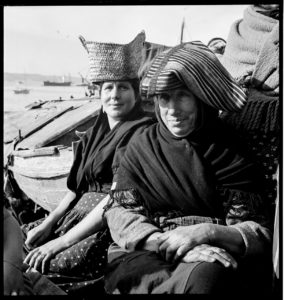

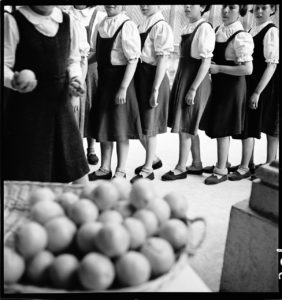

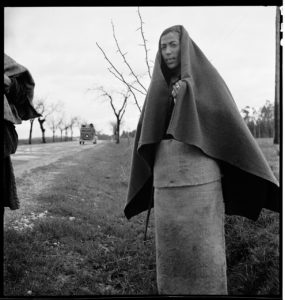

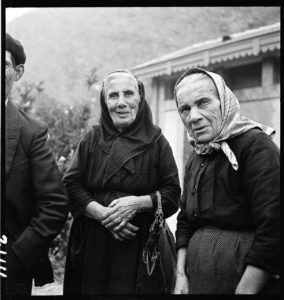

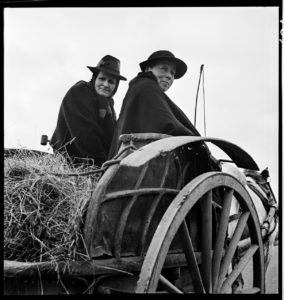

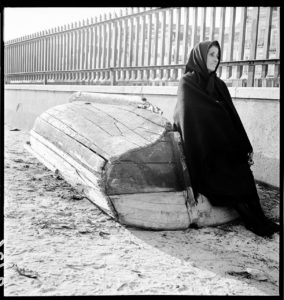

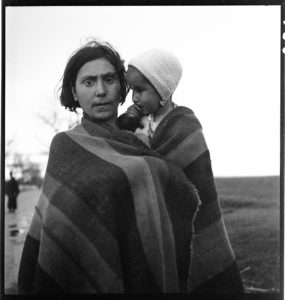

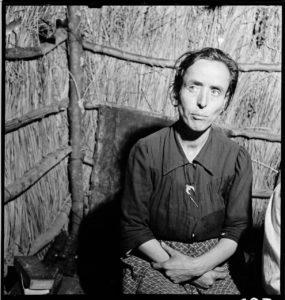

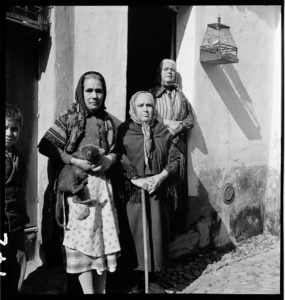

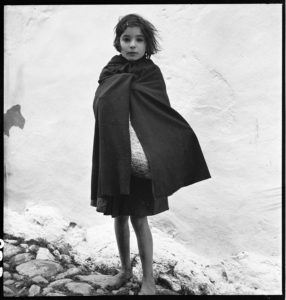

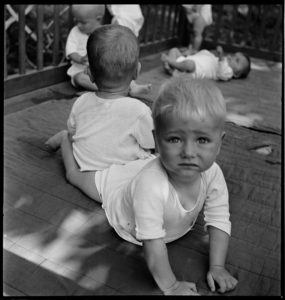

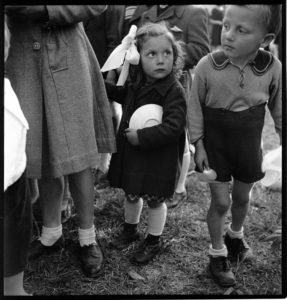

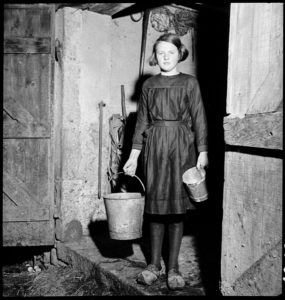

The Thérèse Bonney photograph collection at The Bancroft Library consists chiefly of documentary photographs taken throughout Western Europe during World War II. Bonney (Berkeley class of 1916) photographed all aspects of the war, but focused on its effects on the civilian population.

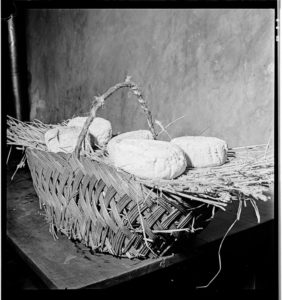

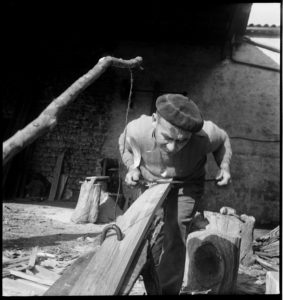

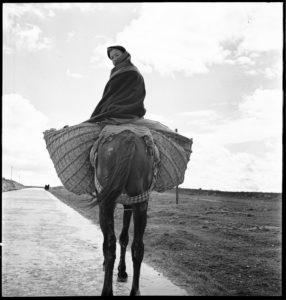

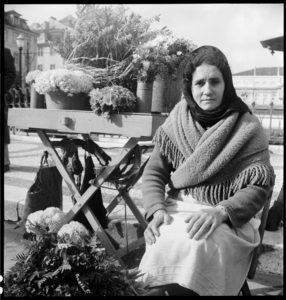

An active humanitarian, Bonney frequently used universal symbols in her work, allowing her images to speak beyond language barriers and leading their viewers to see beyond cultural differences. Her photographs of children were exhibited and published widely, influencing audiences to contribute to relief efforts for innocent victims of war. But the images throughout her archive feature another prominent symbol — women. Old women, young women, mothers, sisters, friends, neighbors; always at work, usually together, forever the epitome of personal sacrifice for the greater good. In honor of Women’s History Month, the Bancroft Library’s Pictorial Unit presents this collection of newly digitized images from the Thérèse Bonney Photograph Collection. The Finding Aid to the Thérèse Bonney Photograph Collection circa 1850-circa 1955 is available through the Online Archive of California. The finding aid includes digital images for Series 6: France, Germany 1944-1946. Images for Series 3: Carnegie Corporation Trip: Portugal, Spain, France 1941-1942 are coming soon, with a preview offered here!

Viewing History through Photographic Negatives: One Chapter in the Travels of the Black Panther Party International Section

A guest posting by Bancroft researcher E. Rafael Perez

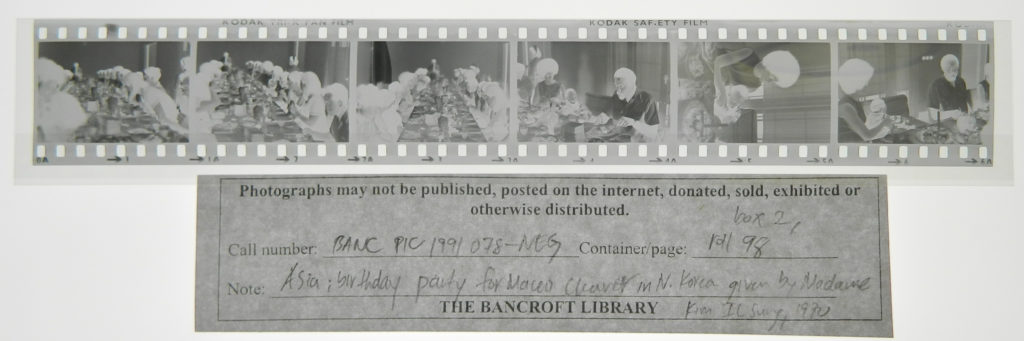

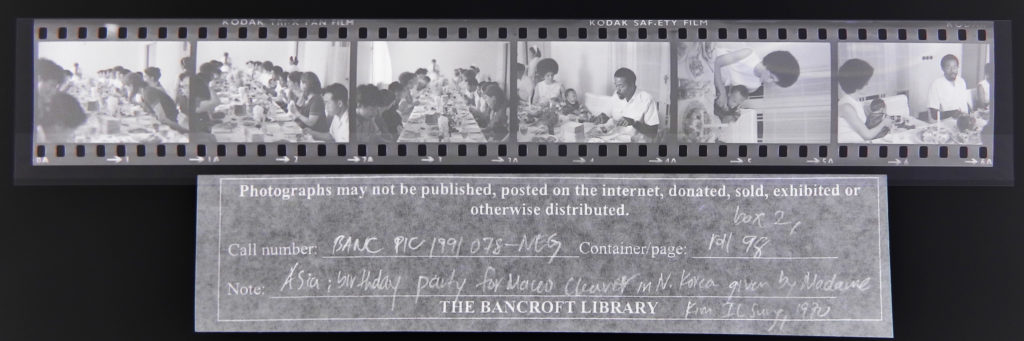

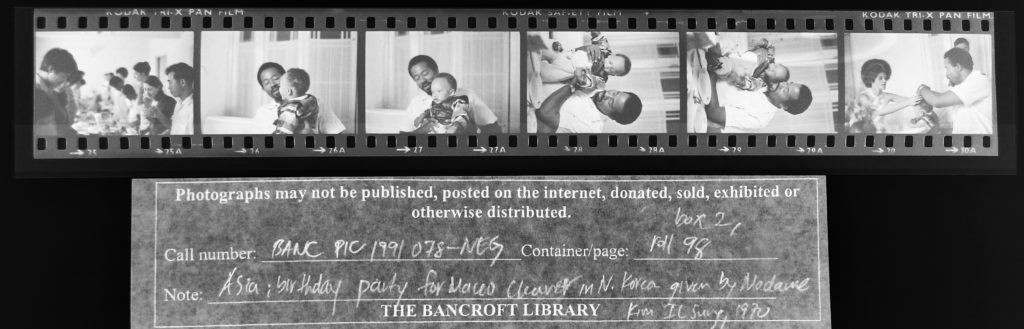

We are happy to present a guest posting by researcher E. Rafael Perez, who shares his experience viewing original photographic negatives in the Bancroft reading room. Negatives, often with no matching prints extant, are made available by appointment with a week’s notice. Researchers may make their own reference snapshots for personal study, as illustrated below, and may place photo orders for high quality digital imaging of selected items.

Since being acquired by the Bancroft Library, the Eldridge Cleaver Papers have given scholars a glimpse into his eclectic experiences. Spanning his early days as Minister of Information for the Black Panther Party, continuing into his time in exile as head of the Black Panther Party’s International Section, and following right on through to his eventual return to the United States—after which he served time in prison, became a born-again Christian and made appearances in support of the Republican Party—the Cleaver Papers and the Eldridge Cleaver Photograph Collection provide context into a complex and layered life. The rarely-seen photographic negatives found in the Eldridge Cleaver Photograph Collection provide consequential traces of life events not covered by other parts of the collection.

For the uninitiated, photographic negatives are the in-camera originals of 20th century photography, in the form of sheets or strips of film in which the darkest areas of a photographed subject appear lightest and the lightest appear darkest. At the Bancroft Library, negatives are stored at 40 degrees Fahrenheit and 30 percent relative humidity. Interested parties make an appointment ahead of time to schedule a viewing, as negatives must spend some time acclimatizing before use. This process highlights archivists’ challenge of balancing the best practices of presentation to the researcher and the best methods of preservation. Nevertheless, examining the over 480 35-millimeter negatives of the Eldridge Cleaver Photograph Collection provides fertile ground for historical exploration.

In 1970 Eldridge and Kathleen Cleaver traveled to North Korea, in part because Eldridge had helped organize the United States Anti-Imperialist Delegation. The delegation traveled between North Korea, China, the USSR, and Vietnam in search of models of self-sufficiency during the Cold War. The delegation consisted of representatives from various political and media organizations. (A full list of delegation participants is available online via the Wilson Center.) At the time, North Korea sought to project itself as a model for postcolonial development to the decolonizing world. Cleaver’s own disillusionment with this vision of North Korea would not come until later, a shift that is also covered in the Cleaver Papers. While some may believe the photographic negatives to be the unfinished and inconvenient templates of the photograph collection, the negatives provide more possibilities for analysis through their many unprinted strips.

One example of the usefulness of the Cleaver negatives is a series, reproduced in part here, that depicts a birthday party held for Kathleen and Eldridge Cleaver’s son Maceo. The negatives provide an intimate portrait of the event, as the family is flanked by Korean and American attendees. Though these photographs were apparently not printed by Cleaver, we see through them a new thread of information that helps us piece together the visual history of Cleaver’s travels and, more broadly, the exchanges between the Black Panther Party’s International Section and solidarity movements among nations of Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

Rather than using images to simply supplement textual evidence in historical writing, this instance reveals the possibilities for expanding narratives through visual histories. How might we more frequently incorporate the use of photography in its rawest and least edited form—the negative—as a source in the study of history? How might we seek to incorporate visual resources into narratives while still maintaining a critical lens regarding these events? To begin to answer these questions as a community, researchers might begin to look for similar threads within their own source bases.

References

- Bloom, Joshua and Waldo E. Martin. Black Against Empire: The History and the Politics of the Black Panther Party. Berkeley: University of California Press, c2013.

- Malloy, Sean. Out of Oakland: Black Panther Party Internationalism During the Cold War. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2017.

- Wu, Judy Tzu-Chun. Radicals on the Road: Internationalism, Orientalism, and Feminism during the Vietnam Era. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2013.

- Young, Benjamin. “Juche in the United States: The Black Panther Party’s Relations with North Korea, 1969-1971.” In The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 13, Issue 12, No. 2, March 30, 2015.

E. Rafael Perez is a PhD Candidate in the Department of History at the University of Chicago. He is a recipient of the 2018 Mellon Fellowships for Dissertation Research in Original Sources, administered by the Council on Library and Information Resources (CLIR). For more recommendations that reflect the recent rise of rigorous historical research related to the Black Panther International Section, please contact him at erp1[at]uchicago.edu.

Thérèse Bonney: Art Collector, Photojournalist, Francophile, Cheese Lover

Thérèse Bonney aboard the S.S. Siboney, en route to Portugal, 1941. BANC PIC 1982.111 series 3, NNEG box 49, item 19

Pioneering war correspondent and Cal grad Mabel Thérèse Bonney (1894-1978) was decorated with the Croix de Guerre and the Legion d’Honneur by the French government, and the Order of the White Rose of Finland for her work during World War II. Her photographs were exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art, the Library of Congress, and Carnegie Hall during her lifetime. Her work on children displaced by war spurred the United Nations to create their international children’s emergency fund, UNICEF, in 1946, and inspired the Academy Award-winning film The Search in 1948. Yet in the canon of female war photographers that includes contemporaries such as Lee Miller, Margaret Bourke-White, and Toni Frissell, Bonney rarely receives mention. Bonney was a renaissance woman whose life deserves further study, and her collections at the Bancroft Library are ripe for discovery. Manuscript Archivist Marjorie Bryer has processed The Thérèse Bonney papers, and Pictorial Archivist Sara Ferguson has digitized over 2,500 previously inaccessible nitrate negatives from the Thérèse Bonney Photograph Collection.

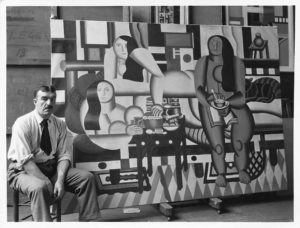

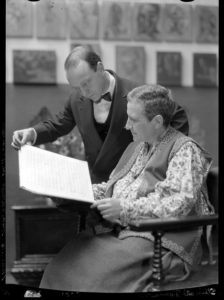

ART CONNOISSEUR

While living in Paris in the 1920s and 1930s, Bonney modeled for fashion designers like Sonia Delaunay and Madeleine Vionnet, and became friends with many of the most famous artists and writers of her day, including Raoul Dufy, Gertrude Stein, and George Bernard Shaw. In 1924 Bonney founded an international photo service that licensed images acquired in France for publication in the U.S. She was often dissatisfied with the images she distributed, and this inspired her to take up photography herself. Bonney wrote about, and took photographs of, many of the artists and writers in her life throughout the twenties, thirties, and forties.

PHOTOJOURNALISM AND WAR RELIEF EFFORTS

Bonney photographed throughout Europe during World War II, focusing on the effects of war on the civilian population. Her photographs of children were particularly moving and resulted in her most famous work, the exhibit and book, Europe’s Children. Bonney was actively involved with relief efforts after the war, particularly in the Alsace region of France. She also founded a number of organizations dedicated to promoting friendship between citizens of France and the United States, and improving Franco-American political relations. One effort, the Chain d’Amite, encouraged French families to open their homes to American G.I.s; another, Project Patriotism, inspired airmen who were shot down in France to help the families that had rescued them. Project Patriotism eventually spread to other European countries, including the Netherlands. Marjorie’s father-in-law, Peter, was a teenager when Germany invaded the Netherlands during the war. He was sent to live with relatives in the Dutch countryside so he wouldn’t be conscripted. One of Peter’s most moving stories was about the American pilot his family hid when his plane crashed on the family farm. Bonney’s papers include many poignant letters from U.S. soldiers and, while processing the collection, Marjorie wondered what this airman from Brooklyn might have written about his experiences with his Dutch “family.”

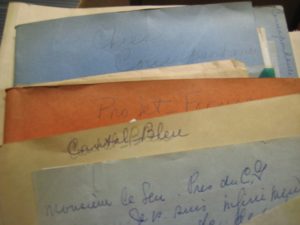

LOVER OF CHEESE

Bonney’s many interests included food and cooking. She and her sister, Louise, wrote a guide to Paris restaurants and a cookbook, French cooking for American kitchens. Her papers include her research on cheese, which she referred to as “Project Fromage.” Series 7 of Bonney’s papers include meticulous notes on various cheeses from France and the Netherlands, “technical” correspondence about cheese, and materials related to tyrosemiophilia — the hobby of collecting cheese labels.

EVERYDAY PEOPLE AND LIFE DURING WARTIME

Bonney documented daily life during wartime across Europe. She recorded entire communities — their families, customs, and industries, their artists and politicians, their schools, and their churches. Her papers and photographs show not only the horrors of war but the hope and perseverance of those who lived through it.

NOW AVAILABLE AT THE BANCROFT LIBRARY!

Newly digitized portions of the pictorial collection include Series 6: France, Germany 1944-1946. This series includes photographs of concentration camps Vaihingen, Buchenwald, and Dachau; Displaced Person camps; Neuschwanstein Castle; and Hermann Göring’s Collection of art looted by the Nazi’s. It also includes many images of the heavily bombarded town of Ammerschwihr in Alsace, France and war relief efforts there. Future digitization efforts will focus on Series 3, Carnegie Corporation Trip: Portugal, Spain, France 1941-1942. This series consists of images taken while on a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York to document the effects of war on civilian populations. It includes images of military personnel, civilian industries, and Red Cross operations. Famous personalities pictured in this series include Pierre Bonnard, Henri Matisse, Georges Roualt, Gertrude Stein, Philippe Petain, Raoul Dufy, and Aristide Maillol.

Bonney’s papers help contextualize her photographs. They include correspondence; personal materials; her writings (autobiographical and articles about others); and her files on World War II, Franco-American relations, art, fashion, photography, and cheese.

Both collections are open for research:

Finding Aid to the Thérèse Bonney Photograph Collection, circa 1850-circa 1955 (bulk 1930-1945)

Finding Aid to the Thérèse Bonney Papers

— Marjorie Bryer and Sara Ferguson

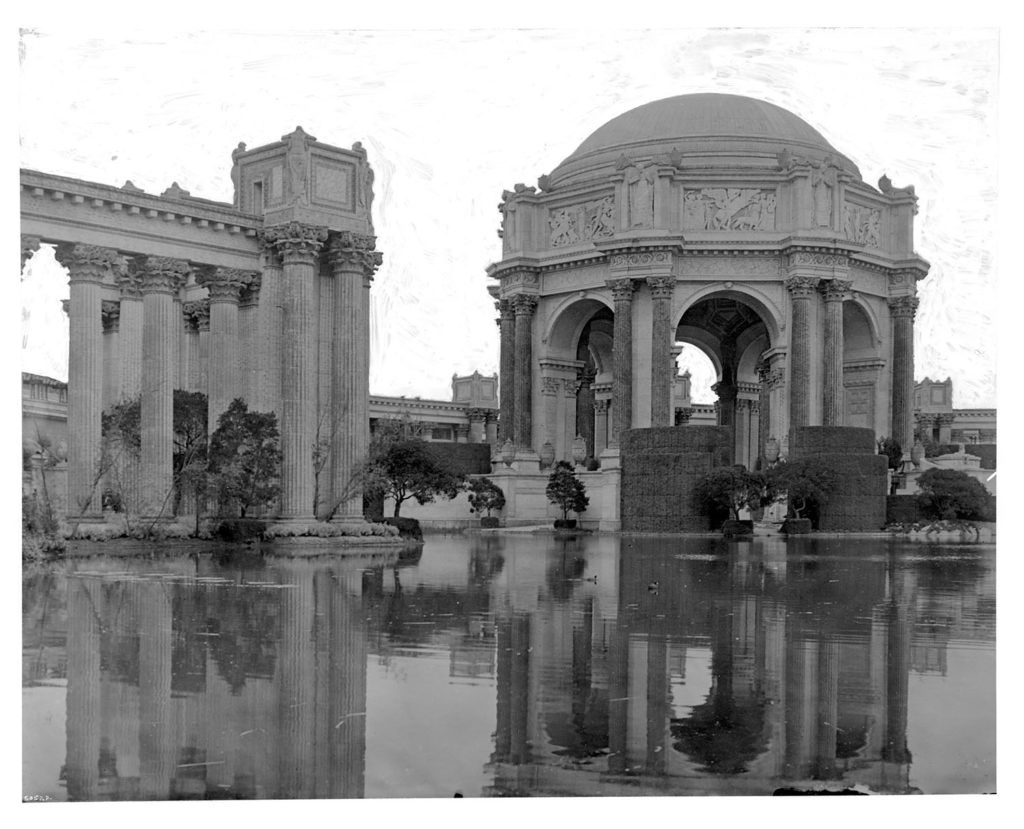

Now Online: Images from Glass Negatives of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition

The Bancroft Pictorial Processing Unit is proud to announce that The Edward A. Rogers collection of Cardinell-Vincent Company and Panama-Pacific International Exposition Photographs has been organized, archivally housed, individually listed, and made (substantially) available online. This work was accomplished over two years, thanks to grant support from the National Endowment for the Humanities and, of course, careful hard work on the part of many library staff.

In this blog posting, Project Archivist Lori Hines describes some of the most challenging (and rewarding) work; preserving and providing access to fragile and often damaged glass negatives.

Handling Glass Plate Negatives: A Lesson in Mindfulness

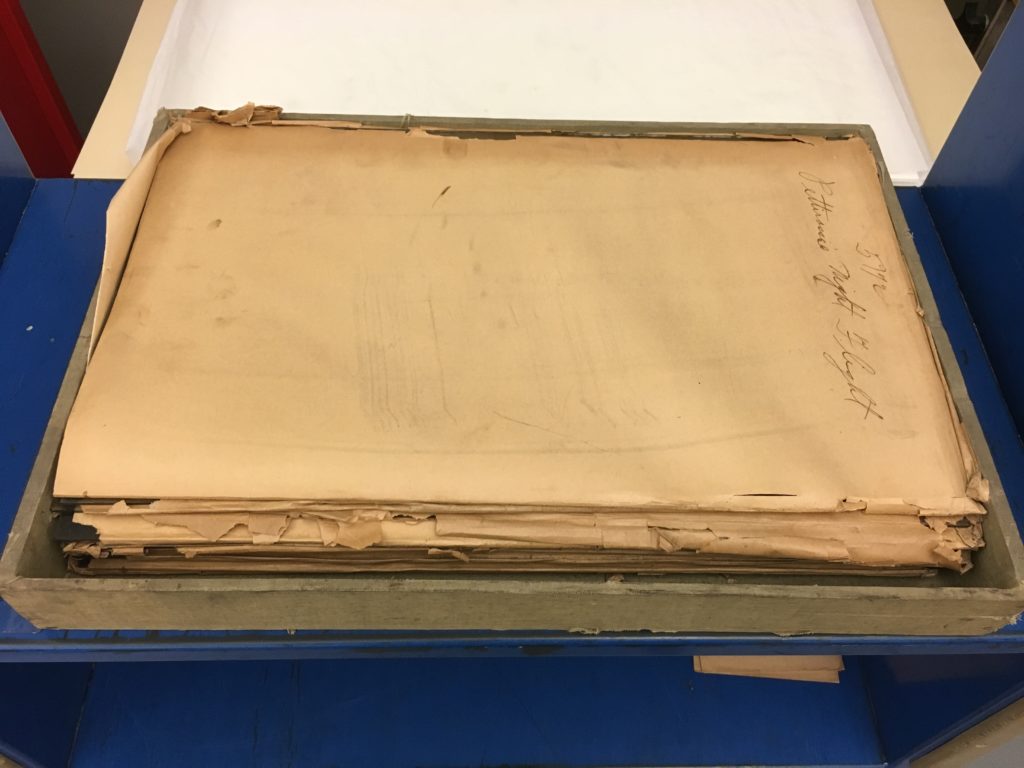

The Rogers collection of Panama Pacific International Exposition photographs, received as a gift in 2014, includes over 2,000 glass negatives. These fragile items required special handling and archival containers with padding. Hardest to work with were approximately 150 oversize glass negatives ranging from 11 x 14 inches to 12 x 20 inches. Antique glass can become brittle and, of course, is heavy. From handling to wheeling the negatives back and forth to the conservation department and the digital lab, one had to be very conscious of every move and step taken.

This first photo shows how the negatives were received in the library. Note they have no padding between the plates and there are only original, brittle sleeves to protect them. A stack of ten or fifteen is very heavy and getting your fingers under one, to lift it off the stack, is challenging. The weight of the negatives on top of each other is also a risk — the antique glass can easily crack under the weight.

This photo shows how the negatives have been housed by library staff; vertically with corrugated archival cardboard around each. Our library conservators designed the housing to limit box weight, to provide protective padding, to protect the plates from abrasion as they’re removed, and to make handling safer.

The largest plates, at 12 x 20 inches, needed another housing solution because it was impractical to store them upright, but the weight of one on another was a concern. The Library’s Conservation Department built custom trays to hold each 12 x 20 negative, with just three plates (and their trays) in an archival box that is stored flat on a cabinet shelf.

The negatives are handled on the long side of the glass to offer best support and, during the cleaning, housing, and inventory process, are rested on a piece of thin foam padding to buffer any impact with the work table.

About 10% of the negatives arrived broken. To be digitized, we had to re-piece the broken negatives together on a supporting sheet of glass, like a puzzle, then hand it off immediately to the photographer in the Library’s Digital Imaging Lab. The glass sheet with the broken negative on top was then placed on a light table, so it was lit from behind, to be captured by the digital camera. The light table and camera are visible in the background of this image.

The results were often quite satisfying, as can be seen in this example of a badly broken glass negative that was pieced together.

The finding aid describing and listing the entire Rogers collection, with more than 2,000 digital images, may be viewed at the Online Archive of California.

To browse examples of images scanned from broken plates, try searching the finding aid for “negative is broken”, and navigating through the results, or by browsing this Calisphere website search that retrieves just the broken-plate images.

Special thanks go to Christine Huhn and the staff of the Digital Imaging Lab; Hannah Tashjian, Erika Lindensmith, Martha Little, and Emily Ramos of the Conservation Department; staff of the Library Systems Office and the California Digital Library that worked with us to get the material online; to Gawain Weaver Art Conservation (contractors for preservation and scanning of panoramic film negatives), and to the Bancroft Pictorial Unit team that devoted much or their 2016-2018 work life to this effort: Lori Hines, Lu Ann Sleeper, and a crew of student staff.

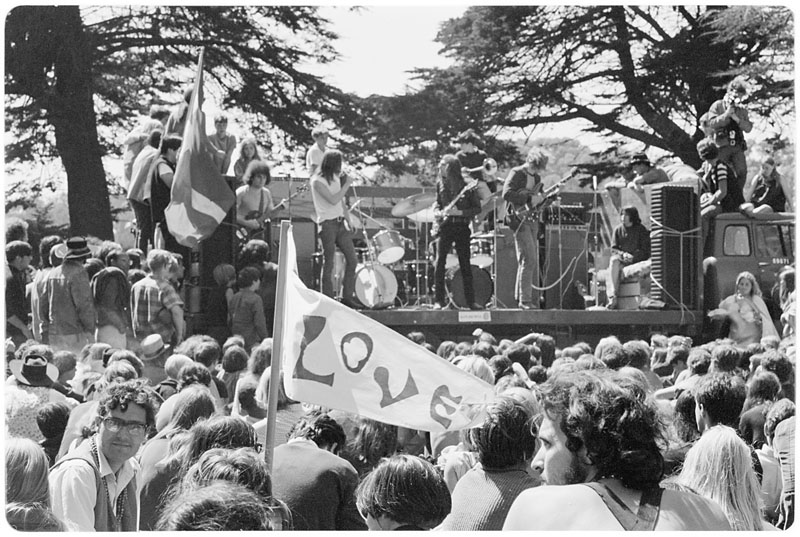

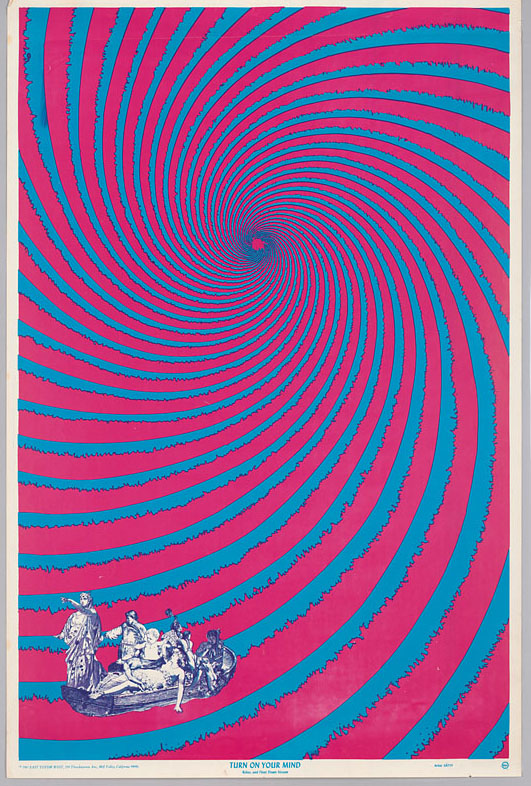

On View Now: The Summer of Love, from the Collections of The Bancroft Library

Marking the 50th anniversary of the Summer of Love, an exhibit in the corridor between Doe Library and The Bancroft Library features Bancroft’s rare and unique collections documenting the world-famous Bay Area counterculture of 1967.

![A young hippie woman with feathers that look like antlers, in day glow face paint, Avalon Ballroom, 1967] Ted Streshinsky, photographer.](https://update.lib.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/cubanc00002896_pm_a_ih.jpg)

This exhibit, prepared by Chris McDonald and James Eason of the Bancroft Library Pictorial Unit will be on view through Fall 2017.

1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition: Stories through Photographs

A guest posting by Seamus Howard, Student Archival Processing Assistant in the Pictorial Unit, Bancroft Library

What makes a photograph good?

As a student working in the Bancroft Pictorial Unit, I’ve been going through hundreds and hundreds of photographs daily. I’ve seen my share of good and bad photos.

One might stand out as “good” due to the lighting, crisp focus, correct staging, and exposure — good cropping perhaps, or just clarity of subject. Ultimately, the answer is a combination of factors, and can be completely subjective.

For me, the most important factor is moment.

The 1915 Panama Pacific International Exposition was full of special moments captured in photographs which continue to shed light on the character and tone of the United States during the early 20th century.

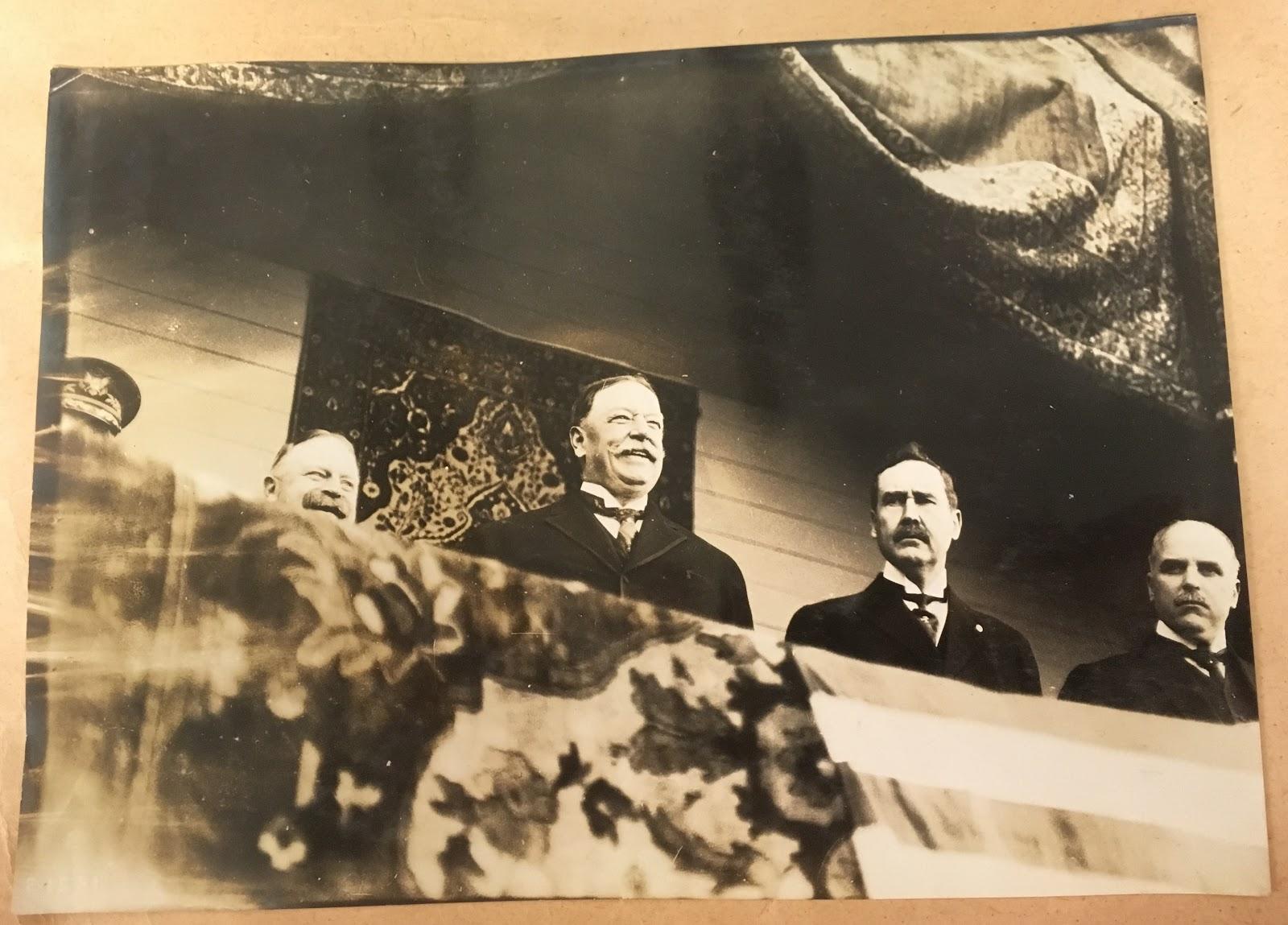

One special moment was former President William Howard Taft visiting the P.P.I.E.

Working to re-house and inventory about 6,700 photographic prints in large, brittle ledger books, I’ve encountered numerous shots of this visit, thoroughly recorded by the Cardinell-Vincent Company, the exposition’s official photographers.

President Taft was an early supporter of the exposition, declaring in early 1911 that San Francisco would be the official home of the fair. He attended the groundbreaking eight months later and returned to San Francisco in 1915 to see the fair in all its glory.

Taft’s visit to the fair was seemingly a large event. He was accompanied wherever he went, soldiers or guards escorting him from building to building. Taft continued to be a very important person at this time. He had lost his reelection to Wilson in 1912, and returned to Yale as a professor of law and government.

Taft visited many of the fair’s popular buildings and exhibits, including the Japanese Pavilion, Swedish Building, Norway Building, and the art gallery and courtyard of the French Pavilion. He met foreign representatives, fair officials, and experienced much of what the fair had to offer.

And President Taft experienced the unique blend of cultures and stories the fair provided. Here, in my favorite photograph of Taft’s time at the fair, he walks through a hall lined with busts in the Swedish building, flanked by guards. Taft seems enveloped by the art and is perfectly framed between his escorts and the lines of busts, drawing your eye towards Taft at the center. This moment makes a great photograph.

The Bancroft Pictorial team continues to house and describe the collection, and will update this blog with more photographs and details as we progress. Stay tuned!

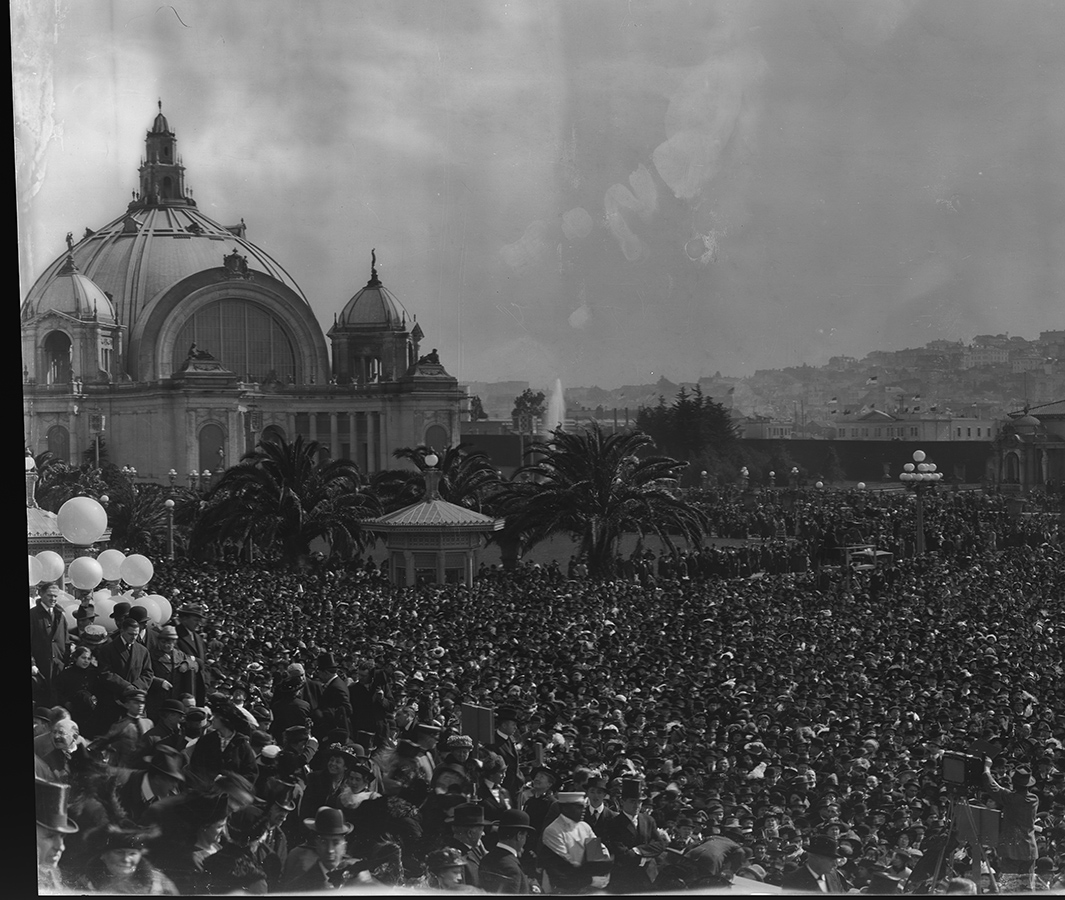

Faces in the Crowd

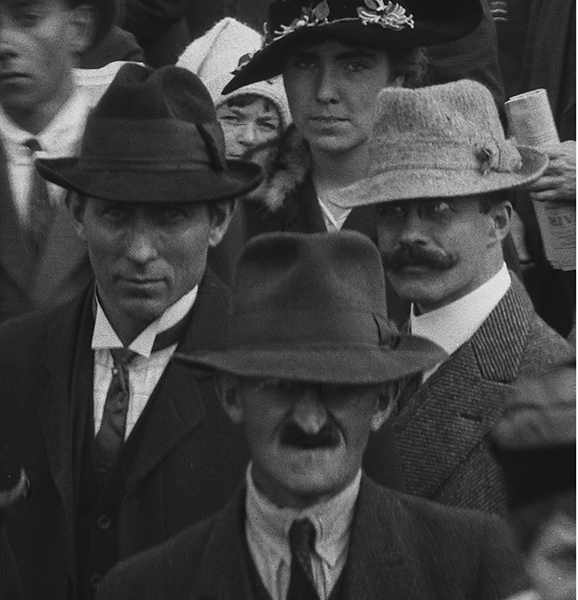

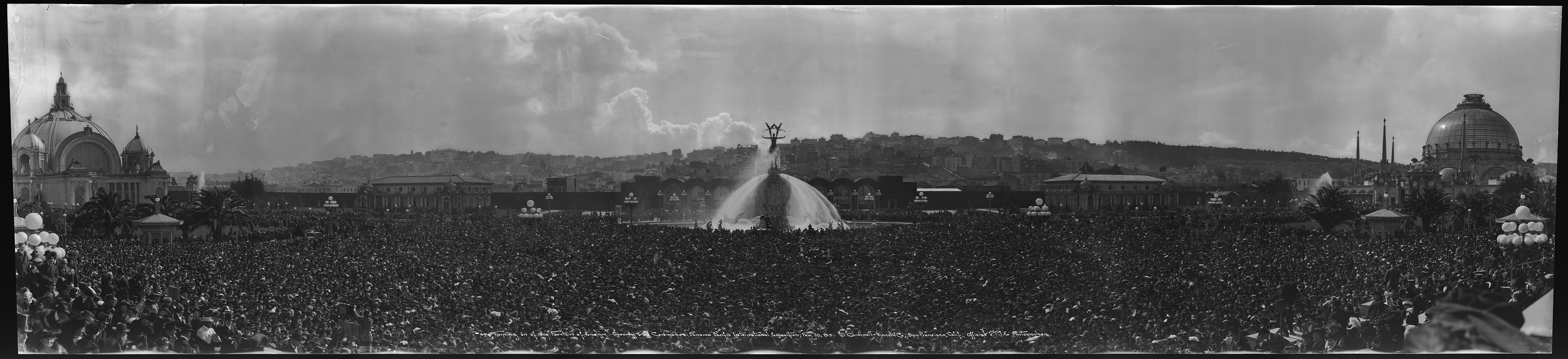

In the Bancroft Library Pictorial Unit, work continues on 115 panoramic Cirkut camera negatives being conserved and scanned as part of our NEH-funded work on the Edward A. Rogers Panama-Pacific International Exposition Photograph Collection.

The digital images produced give the chance to peer into these panoramic scenes and pick out small details – and often our gaze is returned by characters in the crowd, caught some 102 years ago.

The panorama (pictured above) at the Fillmore Street Gate on San Francisco Day, November 2, 1915, is among the best crowd shots, and all the images in this posting are details from it. At center the throng recedes eastward into the distance, down the thoroughfare of popular amusements known as The Zone. At left the crowds fill the Avenue of Progress which leads toward the bay, past the Machinery Palace. At right are the entrance gates, with the ridge of the Pacific Heights neighborhood beyond.

In the crowd there are so many marvelous faces (not to mention terrific hats!) that it is hard to select favorites.

For a “world’s fair” there’s not a lot of diversity in this crowd. But this stylin’ family are holding their own.

###

This fellow’s bound to have a good time, and he’s ready to make memories with his handy portable box camera at the ready.

###

This kid seems to have just made a balloon sale, but it’s serious work.

###

When mixing with hoi polloi, veils and a no-nonsense attitude are necessities for some. Even at a fair.

ESPECIALLY at a fair.

###

This lady is smiling even though she’s enjoying neither an ice cream nor a cigar. Perhaps she knows her hat is at the cutting edge.

It will be over 40 years before Sputnik challenges her design-forward look.

###

Three distinct kinds of trouble.

Make that four.

###

With all the fine hats, how can we choose a winner? – But wait! – Never mind.

The wee chap on the right steals the show!

###

And this favorite auntie’s outstanding chapeau falls victim to another well-accessorized scene-stealer.

###

Work on the Rogers Panama-Pacific International Exposition collection will continue through June of 2018, at which time digital images from over 2,000 negatives will be put online. In the meantime, we will share favorites, along with project updates, on this Bancroft Pictorial Unit blog. Check back again!

James Eason, Archivist for Pictorial Collections, Bancroft Library

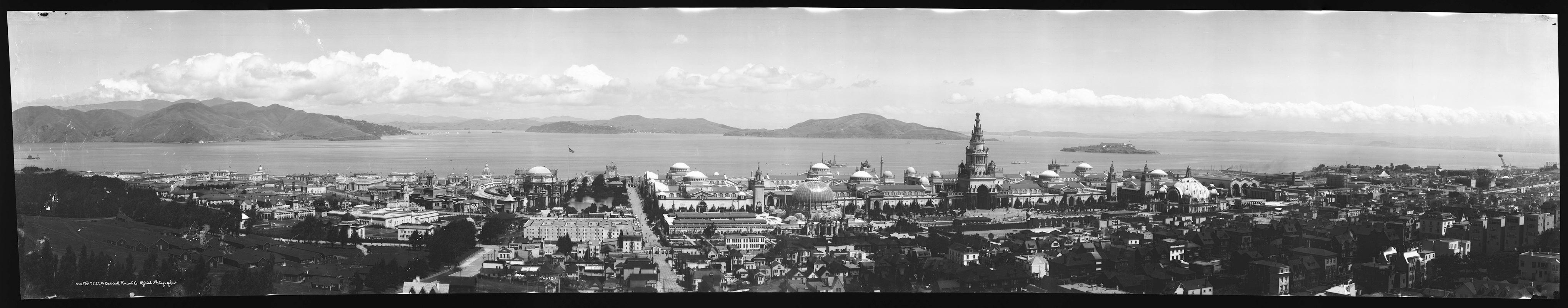

Panoramas Revealed: 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition Photographic Negatives

This year staff in the Bancroft Pictorial Unit have been hard at work housing and preparing to digitize glass plate negatives from the Edward A. Rogers Panama-Pacific International Exposition (PPIE) Photograph Collection. Supported by funding awarded by the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH), about 2,000 glass negatives and 115 panoramic film negatives will be put in order, housed in archival sleeves and boxes, listed, and scanned. Although the work will not be complete and online until June 2018, great progress has been made, and we are starting to see some of the images produced by our digital imaging technicians.

The Rogers Collection was a gift presented in late 2014, just months before the centennial of the opening of San Francisco’s great world’s fair. In addition to the negatives (filling about 40 large boxes), there are also huge ledger books containing about 6,700 photographic prints. These originally served as a visual inventory of the negatives, which were mostly produced by the Cardinell-Vincent Company of San Francisco, official photographers for the PPIE. (Others are by the H.S. Crocker Company that previously held the PPIE photo contract.)

The Cardinell-Vincent photograph archive was broken up many decades ago, with much of it sold off in small auction lots in 1979; but Ed Rogers had collected this material well before that sale. In 2014 his was believed to be the largest PPIE photo collection in private hands – and certainly is the largest quantity of glass negatives known to have survived.

The most challenging images to conserve and digitize are the 115 panoramic negatives. These sweeping views and group portraits, made with a pivoting “Cirkut camera,” are on flammable cellulose nitrate film. Handling, transportation, and storage must meet stringent safety requirements. The rolled negatives were soiled from years of warehouse storage, so they are being cleaned by photograph conservators. They are so large (eight or ten inches high and up to 60 inches long!) that they need to be digitally photographed in segments, and these segments are digitally merged to create a file reproducing the original view.

The first scans from these panoramic negatives have been delivered, and they do not disappoint. The broad views over the bay-front PPIE site, just inside the Golden Gate, are stunning.

There is enough detail present to zoom in and closely study segments of the view.

Even the more prosaic group portraits offer great detail and often capture candid moments at the fringes of the crowd. Some of the crowd views are the most entertaining, and place the viewer in festive moment captured 102 year ago.

As more digitization is completed we will share favorites, along with project updates, on this Bancroft Pictorial Unit blog. Stay tuned!

James Eason, Archivist for Pictorial Collections, Bancroft Library