by Brianna Iswono

Brianna Iswono is a third-year undergraduate student at UC Berkeley majoring in chemical engineering. Throughout the Fall 2024 semester, Brianna worked with Roger Eardley-Pryor of the Oral History Center to earn academic credits through Berkeley’s Undergraduate Research Apprentice Program (URAP). URAP provides opportunities for undergraduates to work closely with Berkeley scholars on cutting edge research projects for which Berkeley is world-renowned. In this post, Brianna reflects on her research about nuclear power as it appeared in the Oral History Center archives.

As a chemical engineering student at UC Berkeley, my coursework only briefly touches on topics of nuclear power and energy. I wanted to learn more and my curiosity deepened as I saw more and more headlines about nuclear energy in news articles and social media. To dive deeper, in the fall of 2024 I joined Berkeley’s URAP (Undergraduate Research Apprenticeship Program) under the mentorship of historian Roger Eardley-Pryor at the Oral History Center, where I analyzed various oral histories and technical reports about nuclear energy. Through this experience, what I discovered was not only a stronger interest in nuclear power, but a field marked by polarizing perspectives and profound complexity—one where simple answers do not exist.

Nuclear power stands as one of the most reliable carbon-free energy sources available today. Unlike fossil fuels, it produces no carbon dioxide during electricity generation, which makes nuclear power a critical tool in the fight against climate change and reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Given the growing urgency for energy facilities to reduce their overall emissions, nuclear power offers a viable option for large-scale, reliable energy production. As former Sierra Club president, mountaineer, biophysicist, and Berkeley Lab energy analyst William E. Siri noted in his oral history in the late 1970s, “Coal is a very dirty fuel… That leaves nuclear as one clean energy source until solar and other energy sources are fully developed.” Today, solar and wind are more developed, but the energy they generate drops when the sun sets or when winds cease. By providing steady, continuous power, nuclear energy complements intermittent renewable sources like wind and solar, ensuring grid stability. This reliability reduces the need for fossil fuel-based backup systems and thus helps mitigate climate change.

However, nuclear power is not without its environmental challenges. The construction and operation of plants can disrupt local ecosystems, particularly since they are often built in rural areas rich in biodiversity and ecological value. Habitat disruption, deforestation, and the high demand for water used in reactor cooling all remain significant concerns. The presence of nuclear plants places an increased strain on local water resources, particularly in underserved regions already facing water scarcity. In the first of his two archived oral history interviews, David Brower, the former executive director of the Sierra Club, the nation’s largest environmental organization, explained about the Club’s consideration of nuclear power, “You certainly haven’t helped the poor by degrading the environment, the working place, by not getting into the battles to protect them from the chemicals that they’re exposed to.”

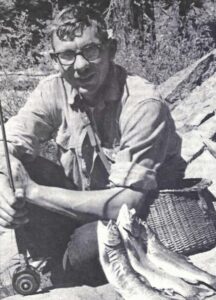

Also, the visual impact of large nuclear facilities can dramatically alter the character of scenic areas. At least in California, public opposition was fueled historically by concern that industrial structures for nuclear power detracts from the natural beauty and environment of rural areas, making them appear stark and out of place. Laurence I. Moss, former Sierra Club president and nuclear engineer, worked directly on construction of nuclear reactors. Moss shared in his oral history, “In my mind it was always a location issue. That was not the right place to put a nuclear power plant, or any industrial facility. I would not want to put a residential development there, anything that would alter the natural environment for the worse.” Moss’s perspective highlights the tension between technological advancement and environmental preservation, underscoring the importance of careful site selection to balance progress with respect for natural landscapes.

Another major challenge, and perhaps the most pressing, is the management of nuclear waste. Nuclear reactors generate long-lived radioactive waste that requires secure, long-term storage, and even the most advanced waste repositories carry the risk of leakage or contamination over the thousands of years that spent nuclear fuel remains toxic. Efforts to manage nuclear waste have included ambitious ideas such as deep-sea disposal or even launching the waste into the sun. However, these approaches fail to fully eliminate the risk of leakage, especially given the exceptionally long timescales over which the waste must remain secure, and they often introduce additional challenges. As Thomas H. Pigford, the founding chair of UC Berkeley’s Department of Nuclear Engineering, explained in his oral history from the late 1990s,“Another more attractive approach is to shoot the radioactive waste into the sun, which would require concentrating it to reduce the weight. And that’s where it belongs, because the sun is so radioactive. But there, the technical challenge or problem is the abort rate of missiles, of space vessels, and so when consulting the people in NASA, we concluded that that was just untenable.” Such unresolved issues remain a central concern for environmental advocates, highlighting the ongoing tension between the potential of nuclear power as a clean energy source and the ecological risks it poses.

Economically, nuclear power presents both opportunities and challenges. Once operational, nuclear reactors have relatively low fuel and operating costs compared to many other energy sources. Uranium, the main fuel used, is highly energy-dense, requiring only small amounts to generate large quantities of energy. This efficiency makes nuclear power a cost-effective solution to meet large-scale energy demands, providing a reliable supply of energy at a lower long-term cost while still delivering the high output needed to sustain industrial and societal needs. After working directly with the economic analysis of nuclear plant construction in the 1960s, Moss shared, “we were able to show that other alternatives, specifically a nuclear power alternative, built in those years could provide power at lower cost than the dams.” Nuclear power also has an extensive reach that goes far beyond reactors, influencing a wide range of industries and technologies. The advancements and expertise gained through working with radiation and the advanced technologies required for waste facilities have helped with the development of new medical technologies used to measure radiation. Professor Pigford was directly involved in establishing the nuclear engineering curriculum at Berkeley and saw its expansion into related medical technologies. In his oral history, Pigford shared “Yes, well, there are plenty of jobs in waste disposal. And they are emphasizing more and more the interaction with the bioengineering program, which, as you probably know, is a new push on the campus. There’s a new department, and they’ve even gone into the field of tomography, which is doing scans on the brain and on the rest of the body. These involve nuclear reactions and so the development of instrumentation for that, techniques of sensing the nuclear radiations and interpreting them, is occupying more and more time.” Pigford’s insight highlights how nuclear engineering graduates have the opportunity to apply their expertise to innovations in health-related technologies, such as medical imaging.

Yet, a major economic challenge of nuclear power is the huge initial investment needed to build a plant. Designing, constructing, and meeting regulatory standards for a single nuclear plant can cost billions of dollars. While the long-term operating costs are lower, the upfront costs to begin production are much higher than those of other energy sources.This creates a significant barrier, particularly for developing countries that may also lack the technical expertise or regulatory infrastructure needed to operate plants safely. In his oral history, Siri captured the economic trade-off and complexity of nuclear power. Siri noted, “The more countries that have nuclear power plants, particularly the less advanced countries, the more likelihood there will be of meltdowns, simply because many such countries don’t have the technical base on which to maintain such an industry.” For these countries, nuclear power offers a chance to advance economically, but it also comes with the greater risk of catastrophic failure.

On the global stage, nuclear technology carries a sense of prestige. Non-nuclear nations often see other nations with advanced nuclear developments as leaders in innovation, which enhances their national pride and elevates their international status. The high demand for uranium to fuel nuclear reactors has led various countries to form alliances or joint ventures, employing any means necessary to secure a share of the advancements in nuclear technology. Roy Woodall, an Australian geologist known for his contributions to the mining and exploration industries, directly engaged with the mining sector to meet the growing global demand for uranium. In his oral history from the early 2000s, Woodall shared, “There was quite a lot of interest from other overseas companies in looking for uranium in Australia, so we formed a joint venture to look for conglomerate-type uranium deposits in Northern Western Australia.” His experience highlights the global scramble for uranium resources, reflecting how the race for nuclear technology has spurred both national and international collaboration.

However, the social risks associated with nuclear power are significant. Public fear of radiation exposure, which can lead to various health risks, has been intensified by past large-scale nuclear accidents like Fukushima and Three Mile Island, along with the media frenzy surrounding them. When reflecting on nuclear concerns during his oral history in 2019, Michael R. Peevey, a UC Berkeley alumnus, former electric utility executive, and previous president of the California Public Utilities Commission, recalled “But we had Chernobyl in Russia, which was a disaster; it’s a lingering disaster today.” Such concern has resulted in widespread resistance to the construction of new nuclear reactors and calls to shutdown existing ones. Grassroots movements and anti-nuclear campaigns have further fueled this opposition, creating a broad social aversion to nuclear power.

David E. Pesonen is a UC Berkeley alumnus, attorney, and environmental activist best known for his leadership role in the battle to defeat a PG&E nuclear power plant at Bodega Bay in the early 1960s. In his oral history recorded in the late 1990s, Pesonen explained his motivation for spreading the anti-nuclear power agenda. “Mainly because of the waste disposal problem. I don’t know the answer to that. I don’t know that anybody does. And also because I think the design of the generation of plants that we are involved with is inherently unsafe.” Despite the advanced safety features of modern plants, the widespread fear and skepticism continue to challenge the nuclear industry, highlighting the complex intersection of technological progress, environmental concerns, and public perception.

After conducting this oral history research and diving into the different aspects of nuclear power, I have come to realize that this field is inherently complex. I am still unsure where I stand in these debates, but one thing is clear: nuclear energy shouldn’t be dismissed outright. A recent LA Times article notes that, as energy-demanding technologies like AI continue developing rapidly, the demand for energy will only increase and all carbon-free options must be considered, especially in light of climate change. At the same time, we cannot ignore the risks that nuclear power poses. I think that the best approach is to carefully consider all non-fossil energy sources, such as nuclear or renewable, to make informed choices. Nuclear power is neither entirely good nor entirely bad; it is a complex and multifaceted technology with the potential for significant benefits and serious risks. Attitudes will likely continue to shift back and forth, but embracing the complexities of nuclear power is important to making wise decisions about its future role in meeting global energy needs. Reflecting on my semester of oral history research, I am grateful to have taken this URAP opportunity, as it gave me valuable insight and a new understanding of nuclear power that I always hoped to explore. Nuclear power is a complicated yet astonishing field, and I hope others can be informed on it to formulate their own stance on how to create a greener future.

Works Cited:

Haggerty, Noah. “Has Nuclear Power Entered a New Era of Acceptance Amid Global Warming?” Los Angeles Times, November 18, 2024. https://www.latimes.com/environment/story/2024-11-18/a-new-generation-finds-promise-in-nuclear-energy.

ABOUT THE ORAL HISTORY CENTER

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. You can find our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

Please consider making a tax-deductible donation to the Oral History Center if you’d like to see more work like this conducted and made freely available online. As a soft-money research unit of The Bancroft Library, the Oral History Center must raise outside funding to cover its operational costs for conducting, processing, and preserving its oral history work, including the salaries of its interviewers and staff, which are not covered by the university. You can give online, or contact us at ohc@berkeley.edu for more information about our funding needs for present and future projects.