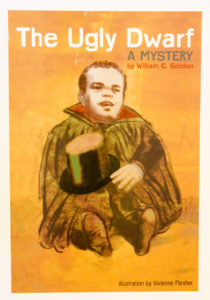

In his novels, Willie Gordon writes about people on the fringes of society: an oversexed dwarf, a dominatrix, an albino sage.

But it’s when discussing his real life that things start to get truly strange.

Gordon once hitchhiked across the globe, sleeping in cemeteries to save money. He had a 27-year marriage with international best-selling Chilean-American author Isabel Allende. His father was a preacher, having invented his own religion, called The Infinite Plan.

“The story of my life is more interesting than anything I could ever write,” says Gordon, 80, in a phone interview.

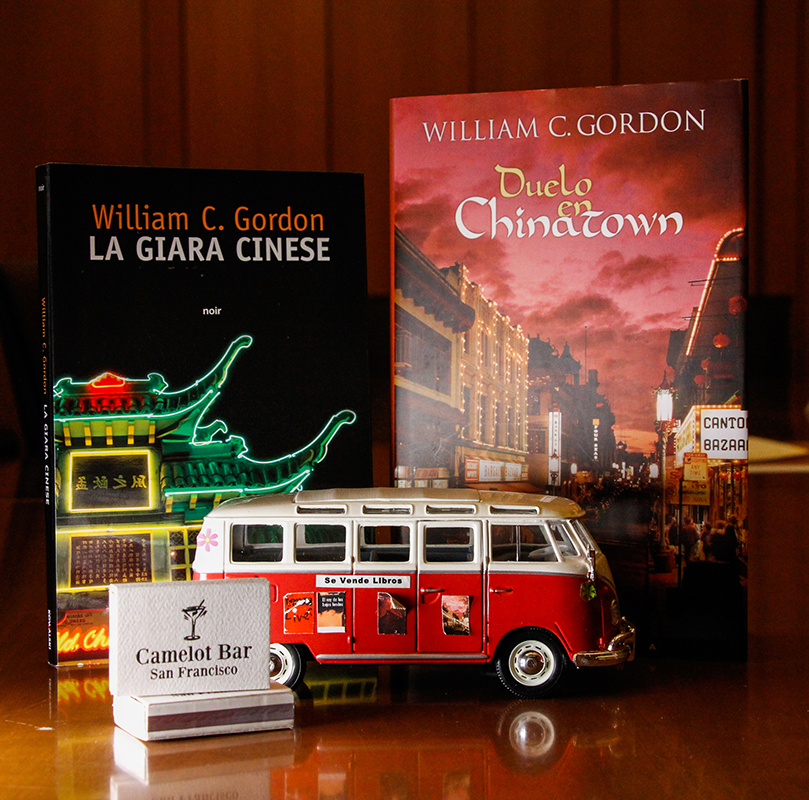

Gordon, who calls Marin County home, also is a supporter of the UC Berkeley Library. A recent donation will provide a “significant boost” to The Bancroft Library’s burgeoning California Detective Fiction Collection — which numbers about 3,000 (and counting) mystery novels set in the Golden State or written by California authors.

“Not only will we be able to add important titles to the collection, but this gift also provides funds for cataloging and processing, enabling us to make the materials available for research much sooner than would otherwise be possible,” says Randal Brandt, who curates the collection, in addition to serving as the head of cataloging at Bancroft.

Gordon also donated manuscripts, ephemera, and 22 volumes of his books in foreign languages.

Having his work immortalized in Bancroft’s collection is “like getting the Nobel Prize,” he says.

“When they make you part of the Library and there’s a chance to give something back, I don’t know, it was just perfect,” he says. “It was just unbelievable. I was so happy with that. Even now, I can’t tell you how wonderful it is.”

A safe haven

Gordon’s affinity for libraries began unexpectedly.

His father died when Gordon was only 6, and after his death, the family moved to a depressed area of East Los Angeles.

“We were broke,” Gordon recalls.

On his first day of school, Gordon walked out of the school’s gate to a startling sight: A gang of five boys were waiting to beat him up. They began to chase him. Gordon, seeking safety, ran into a church.

“I kept yelling for God to help me,” he says.

But Gordon didn’t stand a chance. The boys, he says, “beat the (expletive) out of me.”

Sure enough, the next day, the gang of boys were waiting for him again.

“I figured I could run fast and avoid these guys again,” Gordon says.

And he did run — but this time, he darted straight to a library he noticed on a side street on his way to school. This time, safe inside the library, Gordon avoided a second beating.

And then the learning started.

He asked the librarian to show him the kids section — and to teach him the alphabet — to which she obliged.

“I would go there every day after school,” he says. “And she taught me how to read.”

Man of mysteries

If there’s a typical path to becoming a mystery writer, Gordon didn’t take it.

“I knew (from) the time I was 6 years old I was going to be a writer,” Gordon says. “I knew I was going to be 60 years old. So it all worked out.”

As a second-grader, an enterprising young Gordon shined shoes to make a buck. He would take his shoeshine box, which he built, hop on a streetcar to downtown Los Angeles, and peddle his services on Main Street, “where all the winos were,” he says.

“On the streetcar you would find dime novels that people would leave — discarded mysteries,” he says. “So I would read those.”

And so began his love for the genre.

Gordon gravitated toward writers such as W. Somerset Maugham and Erle Stanley Gardner. As a mystery writer, Gordon describes his fondness for using plot twists in his own work as being inspired, in part, by Maugham (“I like to surprise the reader,” Gordon says). And Gardner, best known for his stories revolving around criminal defense lawyer Perry Mason, was a lawyer, a career Gordon would go on to pursue. “I loved him,” Gordon says of Gardner. “I thought he was fantastic.”

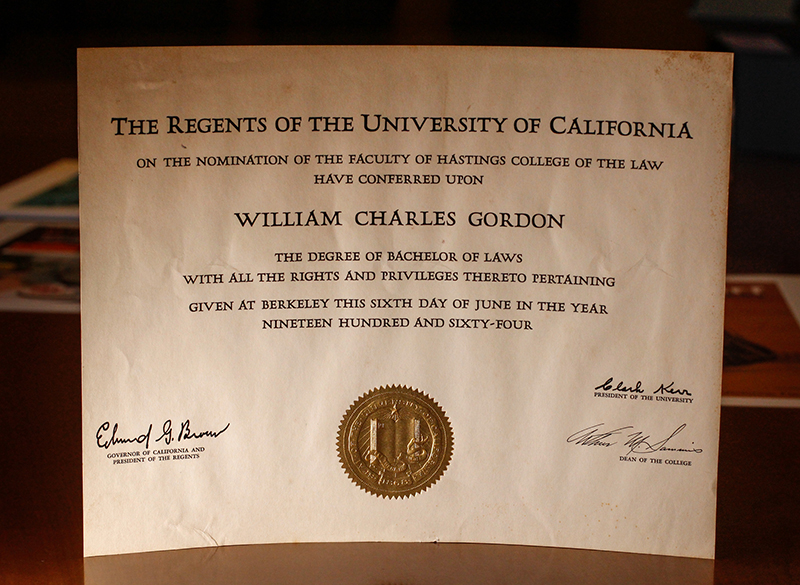

Gordon’s own law career began in 1965, after graduating from UC Hastings College of the Law, in San Francisco, a year earlier. By that time, Gordon had graduated from UC Berkeley with an English degree (“I loved it,” he says) — and had served a stint in the Army. From 1965 to 2002, Gordon represented people with workplace injuries — including many poor Latinos.

“When I was a lawyer, I basically took care of the little guy,” Gordon says. “Those were the people I knew.”

And, perhaps not coincidentally, the “little guy” — characters at the margins of society — eventually made their way into Gordon’s work, after he retired from his legal career and started a second act as a mystery writer — at age 60, as he predicted.

Two decades into his career as a writer, Gordon has released six books in a series of noir mysteries set in 1960s San Francisco that chronicles newspaper reporter Samuel Hamilton. Gordon made Hamilton’s profession a reporter — instead of a cop or an investigator, or even a lawyer — because, as he puts it, “I needed someone who needed to get help from everybody.”

“You have all kinds of people who have no names to the rest of the world,” he says, “but they’re the ones who help you get through life.”

The characters in Gordon’s book include an albino Chinese sage, inspired by a real person Gordon saw in San Francisco; a dominatrix, modeled after his father’s real-life assistant; and an oversexed dwarf, based on Gordon’s father, who he describes as “emotionally a dwarf.”

“Everyone has a place,” he says.

In addition to drawing from real life, Gordon also attributes much of his ideas to what he calls “creative realization.”

“I have to visualize it before I can write about it,” he says. “Because I write about what I see.”

This approach, he says, is something he shared with the celebrated writer Isabel Allende (who in 2014 was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by Barack Obama). Allende’s 1991 novel, “The Infinite Plan,” largely draws from Gordon’s life. The book, Gordon says, is “emotionally accurate.”

“You visualize things as they’re needed in your work,” he explains. “I noticed that Isabel did that, too. I was totally shocked that we shared that. As a writer, that’s all you need.”

Gordon had already known how to tell a story, but, during his relationship with Allende, she helped him hone his craft. Each character has to have a meaning, she taught him, and “how you describe a character emotionally is as important than anything else.”

“And then you do what you’re good at,” he says.

‘All my dreams’

These days, Gordon is working on a collection of short stories. He’s about halfway done.

But at this stage in life, Gordon’s impact extends beyond that of his written work. As a philanthropist, he has given back to causes near to his heart.

In Southern California, he has contributed to the libraries at Whittier High School, where he served as student body president many years ago, and Los Nietos Middle School (Gordon is a Los Nietos alum), and he provided funding for a learning center in Santa Fe Springs. With his donations to Bancroft, he says, “I wanted to save the best for last.”

Gordon is bursting with stories. And after listening to him tell some of them, one thing becomes clear: He has lived a full — and successful — life.

Is there anything he has yet to accomplish?

“I’ve fulfilled all my dreams,” he says.

“I’ve completed everything I’ve wanted to complete,” he adds. “And I’m not finished.”