Tag: BL Europe

Polish

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

Modern day academics and literary scholars have spent considerable time studying the phenomenon related to the use of literature to create national heroes. While, the use of literary forms gives a particular author the means to incorporate the cultural sensitivities, the literary forms that evolve are functions of the society and time in which a particular author was born. Pan Tadeusz as an epic poem is not an exception but reinforces the stereotypes of a particular period through the poetics of Adam Mickiewicz.

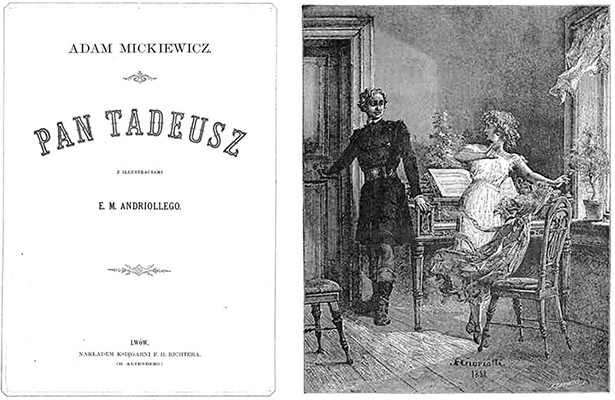

Adam Mickiewicz was born in Nowogródek of the Grand Dutchy of Lithuania in 1798. Nowogródek is today known as Novogrudok and is located in Republic of Belarus. He was educated in Vilnius, the capital of today’s Lithuania. He is recognized as the national literary hero of Poland and Lithuania. However, most of his adulthood was spent in exile after 1829. In Russia, he traveled extensively and was a part of St. Peterburg’s literary circles.[1] There have been several works that track the trajectory of Mickiewicz’s travel and exile. Pan Tadeusz reflects the realities of the partition of the Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth from the perspective of the poet. The drive for liberty and freedom were indeed two traits of Adam Mickiewicz’s life journey that cannot be ignored. The synopsis of the story has been summarized below. Also of interest are the illustrations to accompany the storyline. One prominent illustrator was his compatriot Michał Elwiro Andriolli (1836-1893).[2]

Pan Tadeusz is the last major work written by Adam Mickiewicz, and the most known and perhaps most significant piece by Poland’s great Romantic poet, writer, philosopher and visionary. The epic poem’s full title in English is Sir Thaddeus, or the Last Lithuanian Foray: a Nobleman’s Tale from the Years of 1811 and 1812 in Twelve Books of Verse (Pan Tadeusz, czyli ostatni zajazd na Litwie. Historia szlachecka z roku 1811 i 1812 we dwunastu księgach wierszem). Published in Paris in June 1834, Pan Tadeusz is widely considered the last great epic poem in European literature.

Drawing on traditions of the epic poem, historical novel, poetic novel and descriptive poem, Mickiewicz created a national epic that is singular in world literature.[3] Using means ranging from lyricism to pathos, irony and realism, the author re-created the world of Lithuanian gentry on the eve of the arrival of Napoleonic armies. The colorful Sarmatians depicted in the epic, often in conflict and conspiring against each other, are united by patriotic bonds reborn in shared hope for Poland’s future and the rapid restitution of its independence after decades of occupation.

One of the main characters is the mysterious Friar Robak, a Napoleonic emissary with a past, as it turns out, as a hotheaded nobleman. In his monk’s guise, Friar Robak seeks to make amends for sins committed as a youth by serving his nation. The end of Pan Tadeusz is joyous and hopeful, an optimism that Mickiewicz knew was not confirmed by historical events but which he designed in order to “uplift hearts” in expectation of a brighter future.

The story takes place over five days in 1811 and one day in 1812. The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth had already been divided among Russia, Prussia and Austria after three traumatic partitions between 1772 and 1795, which had erased Poland from the political map of Europe. A satellite within the Prussian partition, the Duchy of Warsaw, had been established by Napoleon in 1807, before the story of Pan Tadeusz begins. It would remain in existence until the Congress of Vienna in 1815, organized between Napoleon’s failed invasion of Russia and his defeat at Waterloo.

The epic takes place within the Russian partition, in the village of Soplicowo and the country estate of the Soplica clan. Pan Tadeusz recounts the story of two feuding noble families and the love between the title character, Tadeusz Soplica, and Zosia, a member of the other family. A subplot involves a spontaneous revolt of local inhabitants against the Russian garrison. Mickiewicz published his poem as an exile in Paris, free of Russian censorship, and writes openly about the occupation.

The poem begins with the words “O Lithuania”, indicating for contemporary readers that the Polish national epic was written before 19th century concepts of nationality had been geopoliticized. Lithuania, as used by Mickiewicz, refers to the geographical region that was his home, which had a broader extent than today’s Lithuania while referring to historical Lithuania. Mickiewicz was raised in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the multicultural state encompassing most of what are now Poland, Lithuania, Belarus and Ukraine. Thus Lithuanians regard the author as of Lithuanian origin, and Belarusians claim Mickiewicz as he was born in what is Belarus today, while his work, including Pan Tadeusz, was written in Polish.”

Polish is a prominent member of the West Slavic language group. It is spoken primarily in Poland and serves as the native language of the Poles who live in various parts of world including the United States. Poles have been involved in the history of the American Revolution from early on. One such example is that of Andrzej Tadeusz Bonawentura Kościuszko who was an engineer and fought on the side of American revolution.

At UC Berkeley, Polish language teaching has been a major part of the portfolio of the Slavic languages that are being taught at the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures. This department was home to UC Berkeley’s only faculty member, Polish poet Czeslaw Milosz (1911-2004), to have ever received the prestigious Nobel Prize in Literature.[4] The tradition of Milosz is continued today in the same department by Professor David Frick. Professor John Connelly in the History department is another luminary scholar of Polish history.

Marie Felde, who reported on his death in the UC Berkeley News Press release on 14th August 2004 noted, “When Milosz received the Nobel Prize, he had been teaching in the Department of Slavic Languages and Literature at Berkeley for 20 years. Although he had retired as a professor in 1978, at the age of 67, he continued to teach and on the day of the Nobel announcement he cut short the celebration to attend to his undergraduate course on Dostoevsky.”[5]

Contribution by Liladhar Pendse

Librarian for East European and Central Asian Studies, Doe Library

Sources consulted:

- Adam Mickiewicz, 1798-1855; In Commemoration of the Centenary of His Death in UNESDOC DIGITAL LIBRARY (accessed 2/21/20)

- Andriolli : Ilustracje do “Pana Tadeusza” (accessed 2/21/20)

- “Pan Tadeusz – Adam Mickiewicz,” Culture.pl (accessed 2/21/20)

- The Nobel Prize in Literature 1980, https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/1980/summary (accessed 2/21/20)

- UC Berkeley News (August 14, 2004), https://www.berkeley.edu/news/media/releases/2004/08/15_milosz.shtml (accessed 2/21/20)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Pan Tadeusz

Title in English: Pan Tadeusz or The Last Foray in Lithuania

Author: Mickiewicz, Adam, 1798-1855.

Imprint: Lwów : Nakładem Księgarni F.H. Richtera (H. Altenberg) , [1882?].

Edition: unknown

Language: Polish

Language Family: Indo-European, Slavic

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign)

URL: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uiug.30112046983406

Other online editions:

- Pan Tadeusz; czyli, Ostatni zajazd na Litwie. Historja szlachecka z r. 1811 i 1812, we dwunastu ksiegach, wierszem, przez Adama Mickiewicza … Wydanie Alexandra Jelowickiego; s popiersiem autora. 1st edtion. Paryz, 1834. (Gallica – Bibliothèque nationale de France)

- Pan Tadeusz; czyli, Ostatni zajazd na Litwie. Historja szlachecka z r. 1811 i 1812, we dwunastu ksiegach, wierszem, przez Adama Mickiewicza … Wydanie Alexandra Jelowickiego; s popiersiem autora. 1st edtion. Paryz, 1834. (Project Gutenberg)

- Pan Tadeusz czyli ostatni zajazd na Latwie. Warszawa : Fundacja Nowoczesna Polska, 2016.

- Pan Tadeusz or The Last Foray in Lithuania: A Story of Life Among Polish Gentlefolk in the Years 1811 and 1812 in Twelve Books. Translated into English by George Rapall Noyes. London : Dent ; New York : Dutton, 1917. (Project Gutenberg )

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Pan Tadeusz; czyli, Ostatni zajazd na Litwie. Historja szlachecka z r. 1811 i 1812, we dwunastu ksiegach, wierszem, przez Adama Mickiewicza … Wydanie Alexandra Jelowickiego; s popiersiem autora. 1st edition. Paryz, 1834.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Portuguese

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

Ó mar salgado, quanto do teu sal

São lágrimas de Portugal!

Quando virás, ó Encoberto,

Sonho das eras portuguez,

Tornar-me mais que o sopro incerto

De um grande anceio que Deus fez?

O salty sea, so much of whose salt

Is Portugal’s tears!

When will you come home, O Hidden One,

Portuguese dream of every age,

To make me more than faint breath

Of an ardent, God-created yearning?

(Trans. Richard Zenith, Message)

Living in a paradoxical era of artistic experimentalism and political authoritarianism, Fernando António Nogueira Pêssoa (1888-1935) is considered Portugal’s most important modern writer. Born in Lisbon, he was a poet, writer, literary critic, translator, publisher and philosopher. Most of his creative output appeared in journals. He published just one book in his lifetime in his native language Mensagem (“Message”). In the same year this collection of 44 poems was published, António Salazar was consolidating his Estado Novo (“New State”) regime, which would subjugate the nation and its colonies in Africa for more than 40 years. Encouraged to submit Mensagem by António Ferro, a colleague with whom he previously collaborated in the literary journal Orpheu (1915), Pessoa was awarded the poetry prize sponsored by the National Office of Propaganda for the work’s “lofty sense of nationalist exhaltation.”[1]

Because of its association with the Salazar’s dictatorship, Mensagem was regarded as a national monument but also as something reprehensible. Translator Richard Zenith describes it as a “lyrical expansion on The Lusiads, Camões’ great epic celebration of the Portuguese discoveries epitomized by Vasco de Gama’s inaugural voyage to India.”[2] At the same time, it traces an intimate connection to the world at large, or rather, to various worlds (historical, psychological, imaginary, spriritual) beginning with the circumscribed existence of Pessoa as a child. Longing for the homeland, as in The Lusiads, is an undisputed theme of Pessoa’s verses as he spent most of his childhood in Durham, South Africa, with his family before returning to Portugal in 1905.

Pessoa wrote in Portuguese, English, and French and attained fame only after his death. He distinguished himself in his poetry and prose by employing what he called heteronyms, imaginary characters or alter egos written in different styles. While his three chief heteronyms were Alberto Caeiro, Ricardo Reis and Álvaro de Campos, scholars attribute more than 70 of these fictitious alter egos to Pessoa and many of these books can be encountered in library catalogs sometimes with no reference to Pessoa whatsoever. Use of identity as a flexible, dynamic construction, and his consequent rejection of traditional notions of authorship and individuality prefigure many of the concerns of postmodernism. He is widely considered one of the Portuguese language’s greatest poets and is required reading in most Portuguese literature programs.[3]

According to Ethnologue, there are over 234 million native Portuguese speakers in the world with the majority residing in Brazil.[4] Portuguese is the sixth most natively spoken language on the planet and the third most spoken European language in terms of native speakers.[5] Instruction in Portuguese language and culture has occurred primarily within the Department of Spanish & Portuguese. Since 1994, UC Berkeley’s Center for Portuguese Studies in collaboration with institutions in Portugal brings distinguished scholars to campus, sponsors conferences and workshops, develops courses, and supports research by students and faculty.

Contribution by Claude Potts

Librarian for Romance Language Collections, Doe Library

Sources consulted:

- Preface to Richard Zenith’s English translation Message. Lisboa: Oficina do Livro, 2016.

- Ibid.

- Portuguese (PORTUG) – Berkeley Academic Guide (accessed 2/4/20)

- Ethnoloque: Languages of the World (accessed 2/4/20)

- CIA World Factbook (accessed 2/4/20)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Mensagem

Title in English: Message

Author: Pessoa, Fernando, 1885-1935.

Imprint: Lisbon: Parceria António Maria Pereira, 1934.

Edition: 1st

Language: Portuguese

Language Family: Indo-European, Romance

Source: Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal

URL: http://purl.pt/13966

Other online editions:

- Mensagem / Fernando Pessoa. – 1934. – [70] p. ; 22,2 x 14,7 cm. From Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal (BNP), http://purl.pt/13965.

- Mensagem. 1a ed. Lisboa : Pereira, 1934.

- Mensagem. Print facsimile from original manuscript in BNP. Lisboa : Babel, 2010.

- Mensagem. Comentada por Miguel Real ; ilustrações, João Pedro Lam. Lisboa : Parsifal, 2013.

- Mensagem : e outros poemas sobre Portugal. Fernando Cabral Martins and Richard Zenith, eds. Porto, Portugal : Assírio & Alvim, 2014.

- Mensagem. Translated into English by Richard Zenith. Illustrations by Pedro Sousa Pereira. Lisboa : Oficina do Livro, 2008

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Old/Middle Irish

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

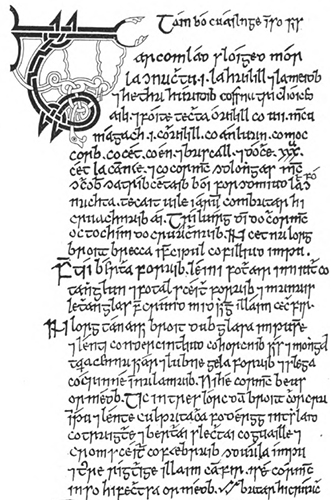

After Greek and Latin, Irish has the oldest literature in Europe, and Irish is the official language of the Republic of Ireland.[1] The prose epic Táin Bó Cúalnge (The Cattle Raid of Cooley) narrates the battles of Irish legendary hero Cúchulainn as he single-handedly guards a prize bull from abduction by Queen Medb and her Connacht army. The tale is the most important in the broader mythology of the Ulster Cycle. The versions we know survive in fragments from medieval manuscripts (notably Lebor na hUidre, the oldest existing text in Irish, the Yellow Book of Lecan, and the Book of Leinster), but the story itself is most likely part of a pre-Christian oral tradition.

In the story, Queen Medb seeks to match her husband Ailill’s wealth through the acquisition of a bull, and she resorts to a raid after her attempt at trade falls through. Inconveniently, all the men in Ulster who might defend the bull have been cursed ill. Cúchulainn, the only man left standing, challenges warriors in Medb’s army to a series of one-on-one combats that culminates in a tragic three-day fight with his foster-brother and friend, Ferdiad. Along the way, Cúchulainn meets his father, the supernatural being Lugh; enjoys supernatural medical care; and transforms into a monster during his battle rages. After Ferdiad’s death, the Ulster men rally and bring the battle to a triumphant finish. Medb’s army is sent packing, but not before she succeeds in smuggling out the bull.

During the early 20th century, the Táin inspired Irish poets and writers such as Lady Gregory and William Butler Yeats, while Cúchulainn served as a symbol for Irish revolutionaries and Unionists alike. The Táin and its legends are routinely taught in UC Berkeley courses such as Medieval Celtic Culture, Celtic Mythology and Oral Tradition, and The World of the Celts. In 1911, the first North American degree-granting program in Celtic Languages and Literatures was founded at Berkeley, and the Celtic Studies Program continues to thrive today. Faculty from the departments of English, Rhetoric, Linguistics, and History participate in teaching regular courses in Irish and Welsh language and literature (in all their historical phases), and in the history, mythology, and cultures of the Celtic world. Breton is also offered regularly, and Gaulish, Cornish, Manx, and Scots Gaelic are foreseen as occasional offerings.[1]

Contribution by Stacy Reardon

Literatures and Digital Humanities Librarian, Doe Library

Sources consulted:

- Celtic Studies Program, UC Berkeley (accessed 1/27/20)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: “Táin Bó Cúalnge” in Leabhar na h-Uidhri

Title in English: Leabhar na h-uidhri: a collection of pieces in prose and verse, in the Irish language, comp. and transcribed about A.D. 1100, by Moelmuiri Mac Ceileachair: now for the first time pub. from the original in the library of the Royal Irish academy, with an account of the manuscript, a description of its contents, and an index.

Author: Anonymous prose epic

Imprint: Dublin, Royal Irish academy house, 1870.

Edition: 1st edition facsimile from original 8th century manuscript

Language: Old/Middle Irish

Language Family: Indo-European, Celtic

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (Cornell University)

URL: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/001058698

Other online editions:

- Táin Bó Cúalnge from the Book of Leinster, Corpus of Electronic Texts (CELT).

https://celt.ucc.ie/published/G301035/index.html

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Fragments of the Táin in Atkinson, Robert. The Yellow Book of Lecan: A Collection of Pieces (prose and Verse) in the Irish Language, in Part Compiled at the End of the Fourteenth Century : Now for the First Time Published from the Original Manuscript in the Library of Trinity College. Dublin: Royal Irish Academy, 1896.

- Recension of the Táin in Atkinson, Robert. The Book of Leinster, Sometime Called the Book of Glendalough: A Collection of Pieces (prose and Verse) in the Irish Language : Compiled in Part About the Middle of the Twelfth Century. Dublin: Royal Irish Academy, 1880.

- The Táin. English translation by Thomas Kinsella and brush drawings by Louis Le Brocquy. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1985.

- The Táin: A New Translation of the Táin Bó Cúailnge. English translation by Ciaran Carson. New York: Viking, 2008.

- Táin Bó Cúalnge, from the Book of Leinster. Annotated English edition by Cecile O’Rahilly. Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1967.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Old Church Slavonic

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

According to the late Slavic linguist Horace Gray Lunt, “Slavonic or OCS is one of the Slavic languages that was used in the various geographical parts of the Slavic world for over two hundred years at the time when the Slavic languages were undergoing rapid, fundamental changes. Old Church Slavonic is the name given to the language of the oldest Slavic manuscripts, which date back to the 10th or 11th century. Since it is a literary language, used by the Slavs of many different regions, it represents not one regional dialect, but a generalized form of early Eastern Balkan Slavic (or Bulgaro-Macedonian) which cannot be specifically localized. It is important to cultural historians as the medium of Slavic Culture in the Middle Ages and to linguists as the earliest form of Slavic known, a form very close to the language called Proto-Slavic or Common Slavic which was presumably spoken by all Slavs before they became differentiated into separate nations.”[1]

At UC Berkeley, OCS has been taught regularly on a semester basis. Professor David Frick currently teaches it. His course description is as follows, “The focus of the course is straight forward, the goals are simple. We will spend much of our time on inflexional morphology (learning to produce and especially to identify the forms of the OCS nominal, verbal, participial, and adjectival forms). The goal will be to learn to read OCS texts, with the aid of dictionaries and grammars, by the end of the semester. We will discuss what the “canon” of OCS texts is and its relationship to “Church Slavonic” texts produced throughout the Orthodox Slavic world (and on the Dalmatian Coast) well into the eighteenth century. In this sense, the course is preparatory for any further work in premodern East and South Slavic cultures and languages.”[2]

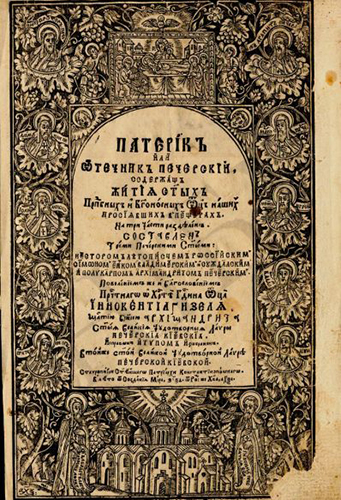

Kievsko-pecherskii paterik is a collection of essays written by different authors from different times. Researchers believe that initially, it consisted of two pieces of the bishop of Suzdal and Vladimir, Simon (1214-1226). One part was a “message” to a monk called Polycarp at the Kyivan cave monastery, and the other part was called the “word” on the establishment of the Assumption Church in Kyiv-Pechersk monastery. Later the book included some other works, such as “The Tale of the monk Crypt” from “Tale of Bygone Years” (1074), “Life” of St. Theodosius Pechersky and dedicated his “Eulogy.” It is in this line-up that “Paterik” represented the earliest manuscript, which was established in 1406 at the initiative of the Bishop of Tver Arsenii. In the 15th century, there were other manuscripts of the “Paterik” like the “Feodosievkaia” and “Kassianovskaia.” From the 17th century on, there were several versions of the printed text.

While there have been several re-editions of this particular book, this Patericon was reprinted in 1991 by Lybid in Kiev. WorldCat indexes ten instances including a 1967 edition that was published in Jordanville by the Holy Trinity Monastery.

Contribution by Liladhar Pendse

Librarian for East European and Central Asian Studies, Doe Library

Sources consulted:

- Lunt, Horace Gray. Old Church Slavonic Grammar. Berlin; Boston: De Gruyter Mouton, c. 2001, 2010.

- Frick, David. “Courses.” Old Church Slavic: Dept. of Slavic Languages and Literatures, UC Berkeley, slavic.berkeley.edu/courses/old-church-slavic-2. (accessed 1/20/20)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Paterik Kīevo-Pecherskoĭ : zhitīi︠a︡ svi︠a︡tykh

Title in English: Patericon or Paterikon of Kievan Cave: Lives of the Fathers

Author: Nestor, approximately 1056-1113., Simon, Bishop of Vladimir and Suzdal, 1214-1226., and Polikarp, Archimandrite, active 13th century.

Imprint: 17–? Kiev?

Edition: unknown

Language: Old Church Slavonic

Language Family: Indo-European, Slavic

Source: National Historical Library of Ukraine

URL: bit.ly/paterik

Other online editions:

- http://litopys.org.ua/paterikon/paterikon.htm (accessed 1/20/20)

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Paterik Kīevo-Pecherskoĭ : zhitīi︠a︡ svi︠a︡tykh. Kīev : [s.n.], [17–?]. (accessed 1/20/20)

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Italian

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

It took centuries before Italy could codify and proclaim Italian as we know it today. The canonical author Dante Alighieri, was the first to dignify the Italian vernaculars in his De vulgari eloquentia (ca. 1302-1305). However, according to the Tuscan poet, no Italian city—not even Florence, his hometown—spoke a vernacular “sublime in learning and power, and capable of exalting those who use it in honour and glory.”[1] Dante, therefore, went on to compose his greatest work, the Divina Commedia in an illustrious Florentine which, unlike the vernacular spoken by the common people, was lofty and stylized. The Commedia (i.e. Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso) marked a linguistic and literary revolution at a time when Latin was the norm. Today, Dante and two other 14th-century Tuscan poets, Petrarch and Boccaccio, are known as the three crowns of Italian literature. Tuscany, particularly Florence, would become the cradle of the standard Italian language.

In his treatise Prose della volgar lingua (1525), the Venetian Pietro Bembo champions the Florentine of Petrarch and Boccaccio about 200 years earlier. Regardless of the ardent debates and disagreements that continued throughout the Renaissance and beyond, Bembo’s treatise encouraged many renowned poets and prose writers to compose their works in a Florentine that was no longer in use. Nevertheless, works continued to be written in many dialects for centuries (Milanese, Neapolitan, Sicilian, Sardinian, Venetian and many more), and such is the case until this day. But which language was to become the lingua franca throughout the newly formed Kingdom of Italy in 1861?

With Italy’s unification in the 19th century came a new mission: the need to adopt a common language for a population that had spoken their respective native dialects for generations.[2] In 1867, the mission fell to a committee led by Alessandro Manzoni, author of the bestselling historical novel I promessi sposi (The Betrothed, 1827). In 1868, he wrote to Italy’s minister of education Emilio Broglio that Tuscan, namely the Florentine spoken among the upper class, ought to be adopted. Over the years, in addition to the widespread adoption of The Betrothed as a model for modern Italian in schools, 20th-century Italian mass media (newspaper, radio, and television) became the major diffusers of a unifying national language.

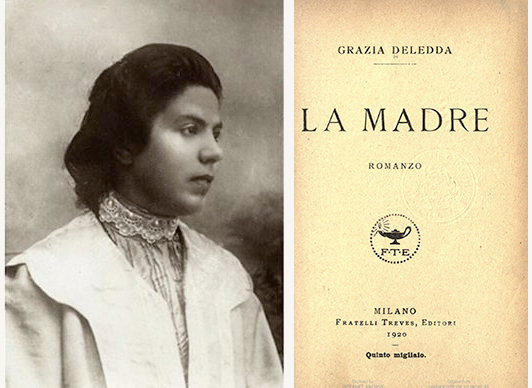

Grazia Maria Cosima Deledda (1871-1936), the author featured in this essay, is one of the millions of Italians who learned standardized Italian as a second language. Her maternal language was Logudorese Sardo, a variety of Sardinian. She took private lessons from her elementary school teacher and composed writing exercises in the form of short stories. Her first creations appeared in magazines, such as L’ultima moda between 1888 and 1889. She excelled in Standard Italian and confidently corresponded with publishers in Rome and Milan. During her lifetime, she published more than 50 works of fiction as well as poems, plays and essays, all of which invariably centered on what she knew best: the people, customs and landscapes of her native Sardinia.

The UC Berkeley Library houses approximately 265 books by and about Deledda as well as our digital editions of her novel La madre (The Mother). It was originally serialized for the newspaper Il tempo in 1919 and published in book form the following year. Deledda recounts the tragedy of three individuals: the protagonist Maria Maddalena, her son and young priest Paulo, and the lonely Agnese with whom Paulo falls in love. The mother is tormented at discovering her son’s love affair with Agnese. Three English translations of La madre have appeared, however, it was the 1922 translation by Mary G. Steegman (with a foreword by D.H. Lawrence) that was most influential in providing Deledda with international renown.

Deledda received the 1926 Nobel Prize for Literature “for her idealistically inspired writings which, with plastic clarity, picture the life on her native island and with depth and sympathy deal with human problems in general.”[3] To this day, she is the only Italian female writer to receive the highest prize in literature. Here are the opening lines of Deledda’s speech in occasion of the award conferment in 1927:

Sono nata in Sardegna. La mia famiglia, composta di gente savia ma anche di violenti e di artisti primitivi, aveva autorità e aveva anche biblioteca. Ma quando cominciai a scrivere, a tredici anni, fui contrariata dai miei. Il filosofo ammonisce: se tuo figlio scrive versi, correggilo e mandalo per la strada dei monti; se lo trovi nella poesia la seconda volta, puniscilo ancora; se va per la terza volta, lascialo in pace perché è un poeta. Senza vanità anche a me è capitato così.

I was born in Sardinia. My family, composed of wise people but also violent and unsophisticated artists, exercised authority and also kept a library. But when I started writing at age thirteen, I encountered opposition from my parents. As the philosopher warns: if your son writes verses, admonish him and send him to the mountain paths; if you find him composing poetry a second time, punish him once again; if he does it a third time, leave him alone because he’s a poet. Without pride, it happened to me the same way. [my translation]

The Department of Italian Studies at UC Berkeley dates back to the 1920s. Nevertheless, Italian was taught and studied long before the Department’s foundation. “Its faculty—permanent and visiting, present and past—includes some of the most distinguished scholars and representatives of Italy, its language, literature, history, and culture.” As one of the field’s leaders and innovators both in North America and internationally, the Department retains its long-established mission of teaching and promoting the language and literature of Italy and “has broadened its scope to include multiple disciplinary and interdisciplinary perspectives to view the country, its language, and its people” from within Italy and globally, from the Middle Ages to the present day.[4]

Contribution by Brenda Rosado

PhD Student, Department of Italian Studies

Source consulted:

- Dante Alighieri, De Vulgari Eloquentia, Ed. and Trans. Steven Botterill, p. 41

- Mappa delle lingue e gruppi dialettali d’italiani, Wikimedia Commons (accessed 12/5/19)

- From Nobel Prize official website: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/1926/summary

See also the award presentation speech (on December 10, 1927) by Henrik Schück, President of the Nobel Foundation: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/1926/ceremony-speech (accessed 12/5/19) - Department of Italian Studies, UC Berkeley (accessed 12/5/19)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: La madre

Title in English: The Woman and the Priest

Author: Deledda, Grazia, 1871-1936

Imprint: Milano : Treves, 1920.

Edition: 1st

Language: Italian

Language Family: Indo-European, Romance

Source: HathiTrust (University of California)

URL: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/006136134

Other online editions:

- La madre. 1st ed. Milano : Treves, 1920. (Sardegna Digital Library)

- The Woman and the Priest. Translated into English by M.G. Steegman; foreword by D.H. Lawrence. London, J. Cape, 1922. (HathiTrust)

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- La madre. 1st ed. Milano : Treves, 1920.

- La Madre : (The woman and the priest), or, The mother. Translated into English by M.G. Steegman; foreword by D.H. Lawrence; with an introduction and chronology by Eric Lane. London : Dedalus, 1987.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Occitan

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

A Lamartine:

Te consacre Mirèio : es moun cor e moun amo,

Es la flour de mis an,

Es un rasin de Crau qu’emé touto sa ramo

Te porge un païsan.

To Lamartine :

To you I dedicate Mirèio: ‘tis my heart and soul,

It is the flower of my years;

It is a bunch of Crau grapes,

Which with all its leaves a peasant brings you. (Trans. C. Grant)

On May 21, 1854, seven poets met at the Château de Font-Ségugne in Provence, and dubbed themselves the “Félibrige” (from the Provençal felibre, whose disputed etymology is usually given as “pupil”). Their literary society had a larger goal: to restore glory to their language, Provençal. The language was in decline, stigmatized as a backwards rural patois. All seven members of the Félibrige, and those who have taken up their mantle through the present day, labored to restore the prestige to which they felt Provençal was due as a literary language. None was more successful or celebrated than Frédéric Mistral (1830-1914).

Mirèio, which Mistral referred to simply as a “Provençal poem,” is composed of 12 cantos and was published in 1859. Mirèio, the daughter of a wealthy farmer, falls in love with Vincèn, a basketweaver. Vincèn’s simple yet noble occupation and Mirèio’s modest dignity and devotion mark them as embodiments of the country virtues so prized by the Félibrige. Mirèio embarks on a journey to Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, that she might pray for her father to accept Vincèn. Her quest ends in tragedy, but Mistral’s finely drawn portraits of the characters and landscapes of beloved Provence, and of the implacable power of love still linger. C.M. Girdlestone praises the regional specificity and the universality of Mistral’s oeuvre thus: “Written for the ‘shepherds and peasants’ of Provence, his work, on the wings of its transcendant loveliness, reaches out to all men.”[1]

Mistral distinguished himself as a poet and as a lexicographer. He produced an authoritative dictionary of Provençal, Lou tresor dóu Felibrige. He wrote four long narrative poems over his lifetime: Mirèio, Calendal, Nerto, and Lou Pouemo dóu Rose. His other literary work includes lyric poems, short stories, and a well-received book of memoirs titled Moun espelido. Frédéric Mistral won a Nobel Prize in literature in 1904 “in recognition of the fresh originality and true inspiration of his poetic production, which faithfully reflects the natural scenery and native spirit of his people, and, in addition, his significant work as a Provençal philologist.”[2]

Today, Provençal is considered variously to be a language in its own right or a dialect of Occitan. The latter label encompasses the Romance varieties spoken across the southern third of France, Spain’s Val d’Aran, and Italy’s Piedmont valleys. The Félibrige is still active as a language revival association.[3] Along with myriad other groups and individuals, it advocates for the continued survival and flowering of regional languages in southern France.

Contribution by Elyse Ritchey

PhD student, Romance Languages and Literatures

Source consulted:

- Girdlestone, C.M. Dreamer and Striver: The Poetry of Frédéric Mistral. London: Methuen, 1937.

- “Frédéric Mistral: Facts.” The Nobel Prize. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/1904/mistral/facts. (accessed 11/12/19)

- Felibrige, http://www.felibrige.org (accessed 11/12/19)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Mirèio

Title in English: Mirèio / Mireille

Author: Mistral, Frédéric, 1830-1914

Imprint: Paris: Charpentier, 1861.

Edition: 2nd

Language: Occitan with parallel French translation

Language Family: Indo-European, Romance

Source: Gallica (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

URL: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k64555655

Other online editions::

- An English version (the original crowned by the French academy) of Frédéric Mistral’s Mirèio from the original Proven̨cal under the author’s sanction. Avignon : J. Roumanille, 1867. HathiTrust

- Mireille, poème provençal avec la traduction littérale en regard. Paris, Charpentier, 1898. HathiTrust

- Mirèio : A Provençal poem. Translated into English by Harriet Waters Preston. London, T.F. Unwin, 1890. Internet Archive (UC Riverside)

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Mireille : poème provençal. Traduit en vers français par E. Rigaud. Paris : Librairie Hachette, 1881.

- Mireio : pouemo prouvencau, avec la traduction littérale en regard. Paris : Charpentier, 1888.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Bosnian-Croatian-Serbian

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

In 1919, following World War I and the Paris Peace Conference, the country later called Yugoslavia came into existence in Southeast Europe. However, the country’s name from 1918 to 1929 was the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. After World War II, this country was renamed the Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia in 1946. It included the republics of Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Serbia, Montenegro, Slovenia, Macedonia, and the autonomous provinces of Vojvodina and Kosovo. The language that was known as Serbo-Croatian was spoken in nearly all of Yugoslavia. In 1991, in the aftermath of the dissolution of Yugoslavia after a period of protracted civil war, all of these constituent parts eventually became independent. First, Slovenia, Croatia, and Bosnia-Herzegovina became independent in 1991. Serbia and Montenegro were joined, under the name Yugoslavia in 2003 and under the name Serbia-Montenegro in 2006. Thus Serbia as such became a separate country only in 2006 when Montenegro proclaimed independence. Kosovo proclaimed independence in 2008 with the support of the United States and allies. Slovenian and Macedonian were already separate languages. However, outside the formerly united country, the name Bosnian-Croatian-Serbian (BCS) became accepted to denote three different languages that are nearly identical to each other in grammar and pronunciation. However, there are some significant differences in vocabulary. Bosnian and Croatian use a Latin based script while Serbian uses both this alphabet and the Cyrillic alphabet. The term BCS was in fact established at the Hague tribunal (ICTY), and the legitimacy gained in this way allowed its widespread acceptance.

The study of Serbo-Croatian, later BCS, began at UC Berkeley in the aftermath of World War II. Since then the Library’s collections in these languages have been growing steadily and now represent one of the stronger components of Library’s Slavic collections. At UC Berkeley, the situation dramatically changed with the arrival of Professor Ronelle Alexander in 1978. She has been instrumental in helping the Library build up its exemplary Balkan Studies collections for the last four decades. The diversity of her teaching and research expertise ranges from South Slavic languages (Bulgarian, Macedonian, BCS), literatures of former Yugoslavia, Yugoslav cultural history, South Slavic linguistics, Balkan folklore to East Slavic folklore. Although her primary research accomplishments are in South Slavic linguistics, she has also published research on the most widely known and translated Serbian poet, Vasko Popa, and Yugoslavia’s only Nobel prize winner, the prose writer Ivo Andrić.[1]

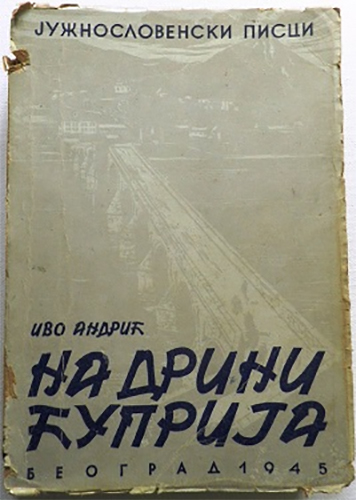

It is challenging to find one single work that would represent the complex nature and relationships between Bosnian, Croatian and Serbian. However, one must note that to this day, the Balkans represent a constantly evolving dynamic mosaic of linguistic diversity that shares a relatively compact geographic topos. For this exhibition, I chose one work that theoretically presents a complicated relationship in Balkans—Ivo Andrić’s prize-winning novel Na Drini ćuprija (“The Bridge on the Drina”) published in 1945.

This historical fiction novel by the Yugoslav writer, Ivo Andrić, revolves around the Mehmed Paša Sokolović Bridge in Višegrad. This bridge is located in Eastern Bosnia and Herzegovina on the Drina River.[2] It was built by the Ottomans in the mid-16th century, and was damaged several times during the wars of the 20th century but each time rebuilt. It was never entirely destroyed and the “original bridge” remains, and is now on the World Heritage List of UNESCO.[3]

The novel chronicles four centuries of regional history, including the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian occupations. The story highlights the daily lives and inter-communal relationships between Serbs and Bosniaks. Bosnian Muslims-Slavs, now also called Bosniaks. Ever since the end of World War II when three major works of Ivo Andrić (The Bridge on the Drina, Bosnian Chronicle, and The Woman from Sarajevo) appeared in print almost simultaneously in 1945. The Woman from Sarajevo has not stood the test of time, though the other two are major works. A later novel, The Damned Yard, is considered much more important. He has been hailed as a major literary figure by both his country’s reading public and by the critics. His reputation soared even higher when he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1961.[4] The Bridge on Drina has been translated into more than 30 languages.

Contribution by Liladhar Pendse

Librarian for East European and Central Asian Studies, Doe Library

Source consulted:

- Ronelle Alexander authored an article on Andric titled “Narrative Voice and Listener’s Choice in the Prose of Ivo Andrić” in Vucinich, W. S. (1995). Ivo Andric Revisited: The Bridge Still Stands. Research Series, uciaspubs/research/92. Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8c21m142 (accessed 7/26/19).

- Ronelle, Alexander. “What Is Naš? Conceptions of “the Other” in the Prose of Ivo Andric.” スラヴ学論集 = Slavia Iaponica = Studies in Slavic Languages and Literatures. 16 (2013): 6-36. (accessed 7/26/19)

- UNESCO World Heritage. “Mehmed Paša Sokolović Bridge in Višegrad.” UNESCO World Heritage Centre, whc.unesco.org/en/list/1260.

- Moravcevich, Nicholas. “Ivo Andrić and the Quintessence of lpendTime.” The Slavic and East European Journal, vol. 16, no. 3, 1972, pp. 313–318. (accessed 7/26/19)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Na Drini ćuprija/ На Дрини ћуприја

Title in English: The Bridge on the Drina

Author: Andrić, Ivo, 1892-1975.

Imprint: Sarajevo: Svjetlost, 1946.

Edition: 1st

Language: Bosnian-Croatian-Serbian (BCS)

Language Family: Indo-European, Slavic

Source: Biblioteka Elektronskaknjiga

URL: https://skolasvilajnac.edu.rs/wp-content/uploads/Ivo-Andric-Na-Drini-cuprija.pdf

Other online editions::

- The Bridge on the Drina. Translated from the Serbo-Croat by Lovett F. Edwards. London: George Allen And Unwin Ltd., [c.1945]. Internet Archive

- In Cyrillic: https://www.scribd.com/doc/185963009/Ivo-Andric-Na-Drini-Cuprija-Cirilica

- Audiobook: https://archive.org/details/IvoAndricNaDriniCuprija4Dio

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Na drini ćuprija. Vishegradska khronika. Sarajevo: Svjetlost, 1946.

- The Bridge on the Drina / Ivo Andrić ; translated from the Serbo-Croat by Lovett F. Edwards ; with an introd. by William H. McNeill. Chicago : University of Chicago Press, 1977.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Yiddish

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

דער גרויסער וועלט-פּראָגרעס האָט זיך אַהין אַרייַנגעכאַפט און האָט איבערגעדרייט די שטאָט מיטן קאַָפּ אַראָפּ, מיט די פֿיס אַרויף.

The great progress of the world has reached Kasrilevke and turned it topsy-turvy.

– From narrator’s foreword to the Kasrilevke stories (1919)

אַיין אַיינשרומפּעניש! ווען האָט געקאָנט ארויס דער צאַפּען, אַיינגעזונקען זאָל ער ווערען? … אַ, ברענען זאָלסט דו, שלים־מזל, אויפ’ן פייער!

און גרונם … דערלאַנגט דעם אַ רוק מיט’ן בייטש־שטעקעל אין זייט אַריין. דאָס פערדעל טהוט אַ פּינטעל מיט די אויגען, לאָזט־אַראָפּ די מאָרדע, קוקט אָן אַ זייט און טראַכט זיךְ׃ פאַר וואָס קומט מיר, אַשטייגער, אָט דער זעץ? גלאַט גענומען און געבוכעט זיךְ! ס’איז ניט קיין קונץ נעמען אַ פערד, אַ שטומע צונג, און שלאָגען איהם אומזיסט און אומנישט!

The driver of the wagon with the water barrel was beside himself! “An empty barrel! … May my helper shrivel up! How could that plug, may it sink into the earth, have come out? May you burn up, wretch that you are!” The last remark was addressed to the little horse, as he struck it with the whip handle. The horse blinked, lowered its chin, and looked aside, thinking, “What have I done to deserve this whack? It’s no trick, you know, to hit a dumb animal for no reason whatsoever.”

– From the story “Fires”

Yiddish is the thousand-year-old language of European (Ashkenazic) Jews. Written from right to left in Hebrew characters, it is derived from German and includes many Hebraic and Slavic elements. It is used for everyday purposes as well as for a rich variety of religious and secular literature, ranging from medieval times to the 21st century. Most Yiddish users were annihilated during the Holocaust of World War II, yet the language continues to thrive in the United States, Israel, and Europe.

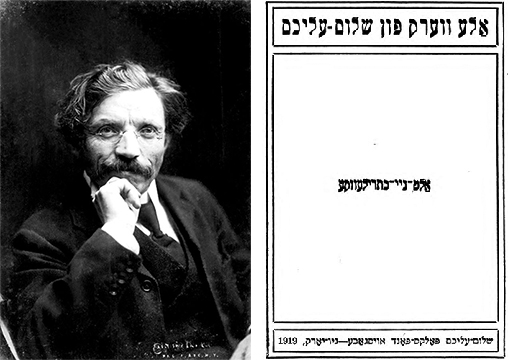

Arguably the best-known Yiddish writer, Sholem Aleichem (Sholem Rabinovich, Ukraine 1859 – United States 1916) was a founding father of modern Yiddish literature. A supreme humorist, he created the literary persona of “Sholem Aleichem” and tapped into the energies of the Eastern European spoken Yiddish idiom. In a variety of genres, he invented modern Jewish archetypes, myths, and fables of unique imaginative power and universal appeal. Sholem Aleichem’s “Tevye” stories provided the basis of the popular mid-20th century musical Fiddler on the Roof. He founded the Folks-bibliotek publishing house (Kiev, 1888) to encourage writers he admired, and identify new talent. In his satirical, yet warm Kasrilevke stories of the 1900s, he created the quintessential fictional shtetl. Its poverty-stricken residents aspired to modernity. Though plagued by backwardness, they continued to dream of redemption.

Following the death in 1916 of the beloved Sholem Aleichem, multi-volume editions of his collected works were published widely. This 1919 edition is printed in the Yiddish spelling prevalent at the time, with transliterations of Germanic linguistic elements; this was meant to help “legitimize” Yiddish (then considered a “jargon”). These transliterations are not used in modern standardized Yiddish orthography. The story “Fires,” from which this selection is taken, underlines the actual lack of progress in the fictional town of Kasrilevke, which prides itself on striving for modernity. The aside, giving voice to the abused horse in the midst of this municipal crisis, is typical of the creative yet plainspoken genius which made Sholem Aleichem so popular.

While the number of native speakers of Yiddish continues to dwindle, Yiddish at Berkeley is thriving. In addition to the esteemed annual conference on Yiddish Culture, we have a wide range of courses dealing with the life and culture of Ashkenazic Jewry, a diverse faculty committed to the preservation and scholarly investigation of Yiddish, and an ever-growing number of students who are pursuing academic futures exploring Jewish culture in the traditional languages of the Jewish people. Students interested in Yiddish at Cal can pursue their interests in the departments of German, Comparative Literature, History, or through the program in Jewish Studies.

Contribution by Yael Chaver

Lecturer in Yiddish, Department of German

Title: Alṭ-nay-Kas̀rileṿḳe

Title in English: Old-New Kasrilevke

Author: Sholem Aleichem, 1859-1916

Imprint: Nyu-Yorḳ : Shalom-ʻAlekhem folḳs-fond, 1919.

Edition: in Ale Verk, Sholom Aleichem

Language: Yiddish

Language Family: Indo-European, Germanic

Source: The Internet Archive (Yiddish Book Center)

URL: https://archive.org/stream/nybc200084

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Sholem, Aleichem. Alṭ-nay-kas̀rileṿḳe. Nyu-Yorḳ: Shalom-ʻAlekhem folḳs-fond, 1919.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Irish

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

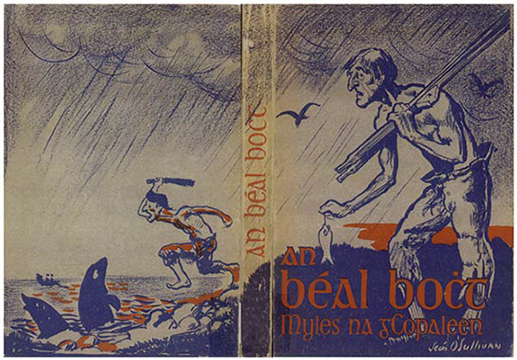

An Béal Bocht (1941), or The Poor Mouth, written by Brian O’Nolan (Ó Nualláin) under the pseudonym Myles na gCopaleen, is one of the most famous Irish language novels of the 20th century. O’Nolan, who most famously published works such as At-Swim-Two-Birds and The Third Policeman under the name Flann O’Brien, wrote in both English and Irish as a journalist and author.

O’Brien takes up the subject of the Irish Literary Revival, a movement in the early 20th century spearheaded by such figures as Lady Gregory and W.B. Yeats who tried to repopularize the Irish folklore and raise the ‘language question’ of Ireland. He simultaneously parodies the genre of Gaeltacht autobiography, autobiographies written in Gaelic that emphasize rural life in Ireland, such as An t-Oileánach (The Islandman) by Tomás Ó Criomhthain and Peig by Peig Sayers, and critiques aspects of the revival.

An Béal Bocht begins with the birth of the narrator, Bónapárt Ó Cúnasa, and follows his life in Corca Dorcha, an impoverished town in the west of Ireland. The town’s rurality attracts the elite from Dublin in search of ‘authentic’ Irishness. Corca Dorcha certainly fits the description — it never stops raining, it’s extremely remote, and crucially, everybody speaks only Irish. The large numbers of visitors from Dublin insist that they love the Irish language, and that one should always speak Irish, about Irish, but ultimately they find Corca Dorcha to be too poor, too rainy, and ironically, too Irish. The very authenticity they sought drives them away to bring their search for authenticity elsewhere.

An Béal Bocht is regarded as a masterful satire, deftly critiquing the genre, the Dublin elite who supposedly supported Irish language revival but avoided rural realities, and the state’s failure to maintain authentic Gaeltacht cultures. The title comes from the Irish expression — ‘putting on the poor mouth’ — which means to exaggerate the direness of one’s situation in order to gain time or favour from creditors. In the novel, there is also the repeated phrase, “for our likes will not be (seen) again,” taken directly from An t-Oileánach.

For more than a century, UC Berkeley has been a locus for the study of Irish culture, language, and literature. Faculty from the departments of English, Rhetoric, Linguistics, and History participate teach courses in Irish and Welsh language and literature (in all their historical phases), and in the history, mythology, and cultures of the Celtic world.[1] The Celtic Studies Program offers the only undergraduate degree in Celtic Studies in North America. Following a visit by President Michael Higgins in 2016 to foster relationships between Irish universities and UC Berkeley, the campus’s Institute of European Studies launched the Irish Studies Program.[2] Flann O’Brien’s works are taught in UC Berkeley classes such as Modern Irish Literature and the English Research Seminar: Flann O’Brien and Irish Literature.

Contribution by Taylor Follett

Literatures and Digital Humanities Assistant, Doe Library

Sources consulted:

- Celtic Studies Program, UC Berkeley (accessed 10/1/19)

- Irish Studies Program, Institute of European Studies, UC Berkeley (accessed 10/1/19)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: An Béal Bocht

Title in English: The Poor Mouth

Author: Myles, na gCopaleen (O’Brien, Flann, 1911-1966)

Imprint: Baile Áṫa Cliaṫ : An Press Náisiúnta, 1941.

Edition: 1st edition

Language: Irish

Language Family: Indo-European, Celtic

Source: The Internet Archive (Mercier Press)

URL: https://archive.org/details/FlannOBrienAnBalBochtCs

Other online resources:

- Research guide to Flann O’Brien (UC Berkeley Library)

- Corpus of Electronic Texts (CELT)

- “Cruiskeen Lawn,” Myles na gCopaleen’s newspaper column in Irish Times (1859-2011) and Weekly Irish Times (1876-1958) via Proquest Historical Newspapers (UCB Only)

- Irish poet Louis de Paor speaking (in Irish) discusses An Béal Bocht,

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vyIQI_huU9g.(accessed 6/18/19)

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- O’Brien, Flann. An béal boċt: Nó, an milleánach : Droċ-sgéal ar an droċṡaoġal curta i n-eagar le. Dublin: Eagrán Dolmen, 1964.

- O’Brien, Flann. Translated into English by Patrick C. Power; illustrated by Ralph Steadman. The Poor Mouth: A Bad Story About the Hard Life. New York: Viking Press, 1974.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Spanish (Europe)

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

If you walk down the street in many parts of the world and ask a stranger who fought the windmills, they would most probably answer Don Quixote. But they would not necessarily know the name of its author, Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra (1547-1616). This not-so-prolific dramaturge, poet and novelist has nonetheless had a major impact on the development of Western literature, influencing his English contemporary William Shakespeare, 19th-century French author Gustave Flaubert, and 20th-century Argentine author Jorge Luis Borges, just to name a few.

Cervantes did not come to prominence until much later in his life. His experiences as a soldier, a captive and a witness to the struggles of the Spanish empire shaped his distinctive oeuvre: a literary world of experimentation, as can be seen in his Exemplary Novels (1613), a world in which possibilities of reconciliation between conflictive individuals, ideals and desires remained hollow, inconclusive and, in many cases, without avail. Among other factors, what distinguishes Cervantes’ literary production is its unclassifiable nature, making it hard to try and fit the works in their presumed corresponding genre. One good example is his posthumous work The Travails of Persiles and Sigismunda (1616), where the Byzantine novel is mutilated to such an extent that, at points, it becomes almost unrecognizable.

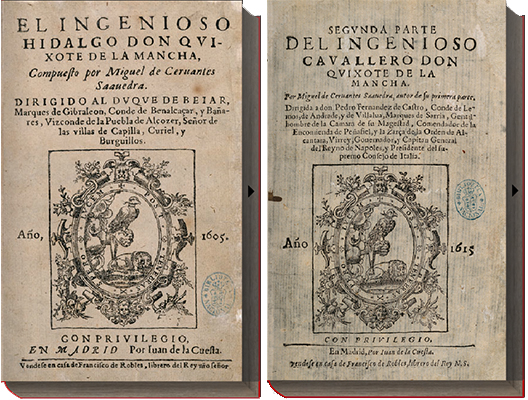

Yet this unfittedness is most evident in Don Quixote (Part I published in 1605; Part II in 1615). The confusion between reality and fiction, the untrustworthiness of the multiple narrators, the intentional errors and misnomers, the three-dimensionalism of Don Quixote’s squire, Sancho, who has a love-hate relationship with his master, the utter destruction of the chivalric world, and the encounter with oppressed minorities are but some of the factors that have undoubtedly contributed to the sustained appeal of Don Quixote. The protagonist, an old man who “loses his mind” reading novels of chivalry, was, in Western literature, a pioneering self-proclaimed “hero.” He offers and imposes his help unto people who rarely take him seriously. Moreover, he only becomes popular, within his diegetic world, when in Part II he is defined by others as a caricature. This caricature remains dominant in the collective imaginary of readers, as can be seen, for example, in Picasso’s well-known depiction of the character.

Although most masterpieces ultimately attempt to challenge a comfortable experience of reading where we readily identify with fictitious characters; Don Quixote still manages to attract the empathy of its readers who may or may not closely identify with the knight-errant. Don Quixote is beaten up, both physically and metaphorically, yet his innocent, albeit selfish at times, intentions have ultimately won the hearts of a diverse audience over the centuries.

Today, the Spanish language, or Castilian as it is referred to in Europe, has grown from around 14 million speakers at the time of Cervantes to 477 million native speakers worldwide. It is now the second most used language for international communication and the most studied languages on the planet.[1] At Berkeley, Spanish is one of the most widely used languages for scholarship after English, particularly in departments such as Anthropology, Comparative Literature, Ethnic Studies, Film & Media, Gender & Women’s Studies, History, Linguistics, Political Science, and Rhetoric. Interdisciplinary graduate programs in Latin American Studies, Medieval Studies, Romance Languages and Literature, and Medieval and Early Modern Studies also require reading of original texts in Spanish.

Nasser Meerkhan, Assistant Professor

Department of Near Eastern Studies & Department of Spanish & Portuguese

Source consulted:

- Elias, D. José Antonio. Atlas historico, geográfico y estadístico de España y sus posesiones de ultramar. Barcelona : Imprenta Hispana, 1848; Hernández Sánchez Barbara, Mario. “La población hispanoamericana y su distribución social en el siglo XVIII,” Revista de estudios políticos, no.78 (1954); López, Morales H, and El español: una lengua viva. Informe 2017. Madrid : Arco Libros, S.L. : El Instituto, 2017.

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: El ingenioso hidalgo Don Quixote de la Mancha

Author: Cervantes Saavedra, Miguel de, 1547-1616.

Imprint: En Madrid : por Iuan de la Cuesta, 1605, 1615.

Edition: 1st

Language: Spanish (Europe)

Language Family: Indo-European

Source: Biblioteca Nacional de España

URL: http://quijote.bne.es/libro.html (requires Flash)

Other online editions:

- El ingenioso hidalgo don Quixote de la Mancha / compuesto por Miguel de Ceruantes Saauedra. En Madrid : por Iuan de la Cuesta, 1605.

- Segunda parte del ingenioso cauallero don Quixote de la Mancha / por Miguel de Ceruantes Saauedra, autor de su primera parte. En Madrid : por Iuan de la Cuesta, 1615.

- The History of Don Quixote. Translated into English by J.W. Clark. Illustrated by Gustave Doré. New York, P.F. Collier, 1871 .

Select print editions at Berkeley:

Considered to be the most translated work every written, the Library has editions in French, German, Hebrew, Armenian, Quechua, and more. The earliest and best illustrated editions reside in The Bancroft Library.

- El ingenioso hidalgo don Quixote de la Mancha. Burgaillos. Published Impresso con licencia, en Valencia : En casa de Pedro Patricio Mey : A costa de Iusepe Ferrer mercader de libros, delante la Diputacion, 1605.

- Segunda parte del ingenioso cauallero don Quixote de la Mancha. En Valencia : En casa de Pedro Patricio Mey, junto a San Martin : A costa de Roque Sonzonio mercader de libros, 1616.

- Vida y hechos del ingenioso Hidalgo Don Quixote de la Mancha. Nueva edicion, corregida y ilustrada con 32 differentes estampas muy donosas, y apropriadas à la materia. Amberes, Por Henrico y Cornelio Verdussen, 1719.

- El ingenioso hidalgo Don Quijote de la Mancha / por Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra ; obra adornada de 125 estampas litográficas y publicada por Masse y Decaen, impresore litógrafos y editores, callejon de Santa Clara no 8. México : Impreso por Ignacio Cumplido, calle de los Rebeldes num. 2, 1842.

- Don Quixote / Miguel de Cervantes ; a new translation by Edith Grossman ; introduction by Harold Bloom. New York : Ecco, c2003.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

![The Languages of Berkeley [fan]](https://update.lib.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/fan_languages-450px.jpg)