Tag: BL Europe

German

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

Although based on a legend transmitted through the popular literature and drama of German-speaking Europe from the late 16th century onward (and which found an English-speaking audience through translation of the texts and Christopher Marlowe’s dramatic adaptation), Goethe’s own version of Faust lives at the heart of the German literary canon. The play’s “pact with the Devil” narrative tells the story of Dr. Faust, who, seeking deeper knowledge than the academy can provide, strikes a bargain with Mephistopheles which requires him to serve Faust and to show him all of the truths in the world. However, should Faust ever become complacent, his life would be forfeit. A series of fantastic, and tragic, events follows, and in the end Faust finds that his life is at risk.

Goethe calls upon a variety of meters to tell his tale, which combines elements of contemporary European society with classical themes. He worked on the play intermittently over the course of nearly 50 years beginning in the 1770s (from which a copied manuscript survives), and after releasing his early efforts as Faust, ein Fragment in 1790, decided that the full play should be published as two parts: Part I, published in 1808, and Part II, published posthumously in 1832. Goethe’s Faust would become highly influential, inspiring music, theater, opera, film, and literature (including Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita) from the 19th century to the present. UC Berkeley Library owns numerous editions of the text, including the initial 1790 publication which was included in a multi-volume set of Goethe’s collected works and is housed in The Bancroft Library. A new project funded by the German Research Foundation called Faustedition has made Faust even more accessible by putting the full text online, and allowing line-by-line reading of variations across editions. Importantly, the project also includes an online archive of Goethe’s handwritten papers and letters, transcribed and searchable, which are related to the development of Faust.

The German language and its literature have been a fixture at Berkeley since the university’s founding. Today, the German Department offers courses at all levels and encompassing the breadth of the Middle Ages to the 21st century. In addition to Modern German, earlier forms of the language including Old Saxon, Old High German, Middle High German, and Early New High German are all taught. Goethe’s writings continue to be studied and read extensively.

Contribution by Jeremy Ott

Classics and Germanic Studies Librarian, Doe Library

Title: Faust

Title in English: Faust

Author: Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von, 1749-1832.

Imprint: Leipzig: Christian Friedrich Solbrig, 1790.

Edition: 1st [?]

Language: German

Language Family: Indo-European, Germanic

Source: Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) | German Research Foundation

URL: http://faustedition.net

Other online editions:

- Faust. Eine Tragödie von Goethe. Zweyter Theil in fünf Acten. (Vollendet im Sommer 1831). Stuttgart und Tübingen, J.G. Cotta, 1833.

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Goethe’s Schriften. 8 vols. Leipzig, G. J. Göschen, 1787-90.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Portuguese (Brazil)

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

“A imaginação foi a companheira de toda a minha existência, viva, rápida, inquieta, alguma vez tímida e amiga de empacar, as mais delas capaz de engolir campanhas e campanhas, correndo.”

“Imagination has been the companion of my whole existence — lively, swift, restless, at times timid and balky, most often ready to devour plain upon plain in its course.” (trans. Helen Caldwell p. 41, Dom Casmurro)

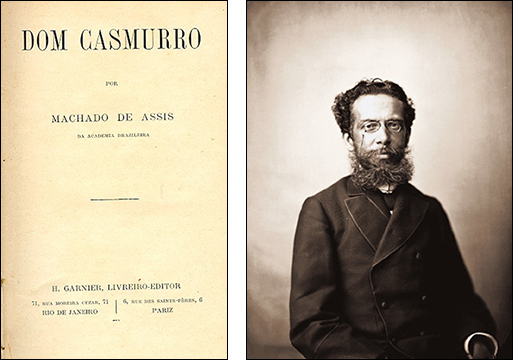

The novel Dom Casmurro is considered a masterpiece of literary realism and one of the most significant works of fiction in all of Latin American literature. The late Brazilian literary critic Afrânio Coutinho called it possibly one of the best works written in the Portuguese language, and it has been required reading in Brazilian schools for more than a century.[1] At UC Berkeley, generations of students in literature courses have been enjoying the rich complexity of this work of prose since the 1950s when the author began receiving recognition worldwide. Indelibly influenced by French social realists such as Honoré de Balzac, Gustave Flaubert and Émile Zola, Dom Casmurro is a sardonic social critique of Rio de Janeiro’s bourgeoisie. The satirical novel takes the reader on a terrifying journey into a mind haunted by jealousy via an unreliable first-person narrative told by Bento Santiago (Bentinho) who suspects his wife Capitú of adultery.

Dom Casmurro was written by multiracial and multilingual Joaquim Maria Machado de Assis (1864-1908) who was an essayist, literary critic, reporter, translator, government bureaucrat. He was most venerated for his short stories, plays, novellas, and novels which were all set in his milieu of Rio de Janeiro. The son of a freed slave who had become a housepainter and a Portuguese mother from the Azores, he grew up in an affluent household under a generous patroness where his parents were agregados (domestic servants).[2] A prodigy of sorts, he began writing at an early age, and quickly ascended the socio-cultural ladder in a country that did not abolish slavery until 1888 with the Lei Áurea (Golden Act).[3] At the center of a group of well-known poets and writers, Machado founded the Academia Brasileira de Letras (Brazilian Academy of Letters) in 1896, became its first president, and was perpetually reelected until his death in 1908.[4] “Even more remarkable than Machado’s absence from world literature,” wrote Susan Sontag, “is that he has been very little known and read in Latin America outside Brazil — as if it were still hard to digest the fact that the greatest author ever produced in Latin America wrote in the Portuguese, rather than the Spanish, language.”[5]

With a population of over 210 million, Brazil has eclipsed Portugal and its former colonies in Africa and Asia and now constitutes more than 80 percent of the world’s Portuguese speakers. Portuguese is the sixth most natively spoken language globally.[6] While European Portuguese (EP) is considered a less commonly taught language in American universities, this is not the case for Brazilian Portuguese (BP) where it has become increasingly popular. The Modern Language Association’s recently released study on languages taught in U.S. institutions, ranked Portuguese as the eleventh most taught language.[7] BP and EP are the same language but have been evolving independently, much like American and British English, since the 17th century. Today, the linguistic variations (phonetics, phonology, syntax, morphology, semantics, pragmatics) are so stark that a non-fluent observer might mistake the two for entirely different languages. In 1990, all Portuguese-language countries signed the Acordo Ortográfico da Língua Portuguesa — a treaty to standardize spelling rules across the Lusophone world — which went into effect in Brazil in 2009 and in Portugal in 2016.[8]

At Berkeley, Brazilian literature is offered for all periods and levels of study through the Department of Spanish and Portuguese’s Luso-Brazilian Program directed by Professor Candace Slater.[9] Her research centers on traditional narrative and cordel ballads, and she was awarded the Ordem de Rio Branco in 1996 — the highest honor the Brazilian government accords a foreigner — and in 2002, the Ordem de Merito Cultural. Other Brazilianists in the department include professors Natalia Brizuela and Nathaniel Wolfson. Graduate students with an interest in Brazil who are part of the Hispanic Language and Literatures (HLL), Romance Language and Literatures (RLL), and Latin American Studies programs delve into all aspects of the nation’s history, culture, and language.[10]

Contribution by Claude Potts

Librarian for Romance Language Collections, Doe Library

Sources consulted

- Coutinho Afrânio. Machado de Assis na literatura brasileira. Academia Brasileira de Letras, 1990.

- “More on Machado,” Brown University Library’s Brasiliana Collection. (accessed 7/19/19)

- Rodriguez, Junius P. Encyclopedia of Emancipation and Abolition in the Transatlantic World. Armonk, NY: Sharpe Reference, 2007.

- Preface to Dom Casmurro: A Novel by Machado de Assis. Translated by Helen Caldwell. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1966, c1953.

- Sontag, Susan. “Afterlives: the Case of Machado de Assis,” New Yorker (April 29, 1990).

- CIA World Factbook (accessed 7/19/19)

- Modern Language Association of America. Enrollments in Languages Other Than English in United States Institutions of Higher Education, Summer 2016 and Fall 2016: Final Report (June 2019). (accessed 7/19/19)

- Vocabulário Ortográfico da língua portuguesa. 5a ed. São Paulo, SP : Global Editora ; Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brasil : Academia Brasileira de Letras, 2009; and Academia das Ciências de Lisboa. Vocabulário ortográfico atualizado da língua portuguesa. Lisboa : Imprensa Nacional-Casa da Moeda, 2012.

- Portuguese (PORTUG) – Berkeley Academic Guide (accessed 7/26/19)

- Hispanic Languages & Literatures, Romance Languages and Literatures, Latin American Studies, UC Berkeley (accessed 7/25/19)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Dom Casmurro

Title in English: Dom Casmurro : novel

Author: Machado de Assis, Joaquim Maria, 1839-1908.

Imprint: Rio de Janeiro; Paris: Garnier, 1899.

Edition: 1st edition

Language: Portuguese

Language Family: Indo-European, Romance

Source: Biblioteca Nacional do Brasil

URL: http://acervo.bndigital.bn.br/sophia/index.asp?codigo_sophia=4883

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- O romance Dom Casmurro de Machado de Assis / Maximiano de Carvalho e Silva. Niterói : Editora da UFF, 2014. Includes the reproduction of the 1899 edition.

- Dom Casmurro. Ilustrações, Carlos Issa ; posfácio, Hélio Guimarães. São Paulo, SP : Carambaia, 2016.

- Dom Casmurro : A Novel. Translated from the Portuguese by John Gledson ; with a foreword by John Gledson and an afterword by João Adolfo Hansen. Oxford University Press, 1997.

- Dom Casmurro: A Novel by Machado de Assis. Translated by Helen Caldwell. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1966, c1953.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Latin

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

The “golden age” of Latin comprises works produced between the first century BCE and the first century CE. The canon of Latin literature includes the works of such authors as Caesar, Cicero, Vergil, Horace, Livy, and Ovid, which frequently make up the core curriculum of any Classics department today.[1] Linguistically speaking, the Latin language became a predominantly literary and administrative language, learned by elite members of society who had an educational or professional need for it.[2] This does not mean that Latin was not spoken anymore, it just means that it ceased being anyone’s first language, and that, eventually, educated inhabitants of the broader Roman empire were bilingual, fluent in both Latin and in their own dialects (which became the Romance languages). The adoption of Latin as the unifying administrative language of the Roman empire — and later as the unifying administrative and liturgical language of the Roman Catholic Church — ensured Latin’s place as a global language through the 18th century.

The most influential ancient Roman author was Marcus Tullius Cicero. When students read Cicero today, they are likely to be assigned his famous speeches, such as the Catiline Orations or the Pro Caelio; one of his philosophical treatises, such as De re publica; or even his letters. What students may not know is that it was one of Cicero’s so-called juvenile works, written before he was 21 years old, that had the most outsized impact on the history of education in the West. Cicero wrote De inventione when he was studying rhetoric as a young man. The title topic “invention” (meaning “discovery”) refers to the first, and most important, task of the orator, which is to develop effective arguments that will persuade a judge. Because De inventione was written as a series of notes, it was easily adaptable to the classroom as a handbook for teaching rhetoric. De Inventione became such a foundational text in the medieval and Renaissance classroom that 322 complete manuscripts survive today.[3] As a result, Ciceronian rhetoric thoroughly permeated medieval and Renaissance intellectual culture and greatly influenced the literature, historiography and political theory of those periods, the fruits of which students continue to learn in humanities courses today.[4]

That Renaissance artists and architects looked to ancient sculptures, paintings, and architecture to inform their designs is well known. Renaissance Latin authors similarly looked to Classical authors as models for writing the “best Latin.” These humanists, as they are called, were reacting against what they saw as idiosyncratic Latin that evolved from the 11th to the 13th centuries to accommodate the highly technical and abstract concepts of theology and philosophy, and they desired a return to what they deemed the best models from antiquity: Cicero for prose and Vergil for poetry.[5] The Italian humanists Pietro Bembo and Jacopo Sadoleto of Italy, and the Belgian humanist Christophe de Longueil, went so far as to declare Cicero the only model for good Latin. The eclectic thinker and scholar Erasmus of Rotterdam (1466-1536) found this idea so ridiculous — because slavish imitation of a single model does not account for individual ability or changing times — that he penned a satirical dialogue titled Ciceronianus that mocked this idea of a single model. In his satire, the character Nosoponus is paralyzed by writer’s block, afraid to write a single word that is not found in Cicero; while Bulephorus endeavors to convince Nosoponus to seek out a greater array of authors as models and to internalize what he learns in order to develop his own style.[6] These arguments for some stylistic flexibility aside, the Renaissance marked the period during which the Latin language became well and truly fixed; by this time, the national vernacular languages had come into their own and Latin had become the domain of an elite educational curriculum.[7] The advantage to us of this fixing is that Latinists today are able to read, with relative ease, a wealth of texts that span more than a millennium.

The study of Latin has many applications and is an important tool for research and study in a variety of fields. Besides Classics, Berkeley students use Latin in courses within the department of Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology,[8] as well as PhD programs in Medieval Studies,[9] Romance Languages and Literatures,[10] and Renaissance and Early Modern Studies.[11]

Contribution by Jennifer Nelson

Reference Librarian, The Robbins Collection, UC Berkeley School of Law

Notes:

- Department of Classics, UC Berkeley

- Leonhardt 2013: 56-74.

- Two examples of manuscripts of De inventione are in the British Library (Arundel MS 348) and in the Kongelige Bibliotek in Denmark (GKS 1998 4°)

- Ward 2013: 167. (accessed 6/24/19)

- The notion that medieval Latin was fundamentally different from Classical Latin was a humanist construct. While, in some cases, there did exist identifiable regional flavors, evidence of certain non-“standard” constructions, or writing conventions developed for specific genres (frequently in the technocratic, bureaucratic, or legal realms), in general Latin did not change in any fundamental way in the period known as the Middle Ages.

- Nosoponus means “suffering from illness”; Bulephorus means “one who gives counsel.”

- Leonhardt 2013: 184-219.

- Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology (AHMA), UC Berkeley

- Program in Medieval Studies Program, UC Berkeley

- Romance Languages and Literatures, UC Berkeley

- Designated Emphasis in Renaissance and Early Modern Studies (REMS), UC Berkeley

Sources consulted:

- Erasmus, Desiderius. Dialogus cui titulus Ciceronianus, sive De optimo genere dicendi (Ciceronianus, or, A Dialogue on the Best Style of Speaking). Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1976.

- Hubbell, H. M. Introduction to Cicero’s De inventione (On Invention), with an English translation by H. M. Hubbell. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1968, xi-xviii.

- Leonhardt, Jürgen (trans. Kenneth Kronenberg). Latin: Story of a World Language. Cambridge, Massachusetts : The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2013.

- Ward, John O. “Ciceronian Rhetoric and Oratory from St. Augustine to Guarino da Verona.” In van Deusen, Nancy, Cicero Refused to Die: Ciceronian Influence Through the Centuries. Leiden: Brill, 2013, 163-196.

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: De inventione ; De optimo genere oratorum ; Topica, with an English translation by H. M. Hubbell

Title in English: On Invention (and other works)

Author: Marcus Tullius Cicero

Imprint: Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1949.

Edition: 1st edition

Language: Latin

Language Family: Indo-European, Italic

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (University of Michigan)

URL: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/api/volumes/oclc/685652.html

Other online editions:

- Erasmus, Desiderius. Dialogus cui titulus Ciceronianus, sive De optimo genere dicendi (Ciceronianus, or, A Dialogue on the Best Style of Speaking). Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1949.

Loeb Classical Library (UCB only), DOI: 10.4159/DLCL.marcus_tullius_cicero-de_inventione.1949

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Czech

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

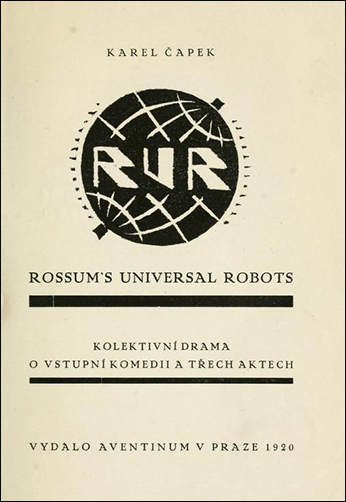

Karel Čapek (9 January 1890 – 25 December 1938) was a Czech writer of the early 20th century. He had multiple roles throughout his career, including playwright, dramatist, essayist, publisher, literary reviewer, photographer and art critic. Nonetheless, he is best known for his science fiction including his novel War with the Newts and the play R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots), which introduced the word “robot” for the first time in the English language.[1] He also wrote many politically charged works dealing with the social turmoil of his time. Largely influenced by American pragmatic liberalism, he campaigned in favor of free expression and utterly despised the rise of both fascism and communism in Europe.

A funny and surreal story of servitude and technology, R.U.R. was Čapek’s first major work for the stage. The play is a gloriously dystopic science-fiction fantasy about robots and the brave new world of the men who mass-produce them. Robots multiply, are bought and sold and gradually take over every aspect of human existence. As people grow idle and stop procreating, the robots rebel and destroy almost the entire human race. The play was first performed in Prague in 1921.

UC Berkeley professor Ellen Langer describes the novel and the title as follows, “The word robot was derived from the Czech robota, which means “forced labor” — like the French word corvée. The play was an instant hit in Europe and was acclaimed in the United States, perhaps because it captured the terror of those times. World War I had barely ended when the Bolshevik Revolution made Europeans fear an uprising by factory workers. To Čapek, an impassioned democrat, the dictatorship of the proletariat seemed as abhorrent as the recently overthrown Austro-Hungarian autocracy. R.U.R. expressed an idealistic yearning that mass production would free people from want, but realism cautioned that industrialization could also usher in an even more powerful tyranny.

The play seems preachy by current standards, but, as Langer says, “this was an era of polemical plays.” It caused such an intellectual stir in London that Čapek sought to explain its message in an essay published in 1923: “We are in the grip of industrialism; this terrible machinery must not stop, for if it does it would destroy the lives of thousands. It must, on the contrary, go on faster and faster, even though in the process it destroys thousands and thousands of other lives . . . A product of the human brain has at last escaped from the control of human hands. This is the comedy of science.” Thus was born a term that promised either service or subjugation, and, over time, robots migrated from fictional characters to functional creations.[2]

The history of teaching Czech at UC Berkeley is closely tied to the history of the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures. Currently, each year, Dr. Langer offers courses in Basic and Continuing Czech. Besides, the language teaching Professor John Connelly of the Department of History specializes in the Modern East and Central European Political and Social History and History of Catholicism. His groundbreaking research on the history of education came to fruition in his critically acclaimed book Captive University: The Sovietization of East German, Czech, and Polish Higher Education, 1945-1956.

Contribution by Liladhar Pendse

Librarian for East European and Central Asian Studies, Doe Library

Sources consulted:

- Čapek, Karel, Peter Majer, and Cathy Porter. R.U.R. [London] : Bloomsbury, [2015], 2015. .

- Abate, Tom. “The Robots Among Us.” SFGate, 9 Dec. 2007.

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: R.U.R (Rossumovi Univerzální Roboti)

Title in English: R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots)

Author: Čapek, Karel, 1890-1938.

Imprint: V Praze: Vydalo Aventinum, 1920.

Edition: unknown

Language: Czech

Language Family: Indo-European, Slavic

Source: The Internet Archive (University of Toronto)

URL: https://archive.org/stream/rurrossumsuniver00apekuoft#page/n0/mode/2up

Other online editions:

- English translation by David Wyllie.

University of Adelaide, 2015: https://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/c/capek/karel/rur - 1922 edition in HathiTrust Digital Library, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/chi.14800394

- Project Gutenberg, http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/13083

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- There are many original Czech editions and English translations in OskiCat.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Icelandic

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

Icelandic literature after the Reformation was primarily the domain of poetry until the mid-19th century. Following a small number of unpublished collections of short stories and folk tales and several published prose translations into Icelandic in the 18th century, currents of European influence encouraged the sustained development of literary prose, at first short stories, which in some cases also drew upon local saga and folkloric traditions. Credit for the first Icelandic novel is generally given to Jón Thóroddsen (1818-1868) for his 1850 work Piltur og Stúlka (Lad and Lass). As scholar and statesman Jón Sigurðsson would write in his introduction to a posthumous edition (1876) of Thóroddsen’s second, unfinished novel Maður og Kona (Man and Woman), “Various attempts have been made in our country before this to compose works of fiction similar to those which had appeared in foreign lands in modern times, which are called in English ‘novels,’ because they draw their material from modern everyday life, and not from ancient events or historical writings, as do the knightly romances; but this story of Thóroddsen’s [Piltur og Stúlka] is the most important of all these tales, and is hence universally conceded to be the first Icelandic novel [translation from Reeves’ 1890 edition of Lad and Lass].”

Born in western Iceland, Thóroddsen traveled to Copenhagen to study law, where he also pursued literary interests as co-creator and editor of a liberal arts annual to which he contributed his own poetry and several short texts (in addition to briefly joining the Danish army in its fight against rebellious Germans). During the winter of 1848-9 he wrote Piltur og Stúlka, which was published in Copenhagen in 1850 (a second edition was published in Reykjavik in 1867). Although indebted to the English romantic love story, this tale of the complicated love between Indriði and Sigríður, which begins and ends in the countryside and includes a journey to Reykjavik at its middle, is highly localized in its descriptions of contemporary Icelandic society. Thóroddsen was a keen observer of character, and his readers were especially drawn to the comic traits with which he endowed some of them. Other aspects of description as well as narrative reveal the influence of the Icelandic sagas. In 1850 Thóroddsen returned to Iceland, where he worked as a bailiff, and nearly completed his second novel before his death in 1868. Piltur og Stúlka has been published in a number of subsequent editions, translated into four languages, and was adapted for the stage in Iceland in 1933. The UC Berkeley Library owns the 1973 reprint of the 1948 edition, which was published in Reykjavik.

The Modern Icelandic language has been taught at the introductory level in UC Berkeley’s Scandinavian Department since 2015, when a pilot program was launched with the assistance of the Institute of European Studies.

Contribution by Jeremy Ott

Classics and Germanic Studies Librarian, Doe Library

Title: Piltur og Stúlka : Dálítil Frásaga

Title in English: Lad and Lass

Author: Jón Thóroddsen, 1818-1868.

Imprint: Kaupmannahöfn : S.L. Möller, 1850.

Edition: 1st

Language: Icelandic

Language Family: Indo-European, Germanic

Source: The Internet Archive (National and University Library of Iceland)

URL: https://archive.org/details/Pilturogstulkada000209560v0JonReyk/page/n6

Other online editions:

- Sigrid: An Icelandic Love Story. Translated from the Danish by C. Chrest. New York: T.Y. Crowell & Co, 1887 in HathiTrust Digital Library.

Select print editions at Berkeley:

Piltur og stúlka: dálítil frásaga. Reykjavík: Helgafell, 1973. Reprint of the 1948 edition.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Catalan

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

I don’t want you to confine my thinking to facts and agreed formulas; I do want, like birds, the liberated wings to fly at any time, now to the right, now to the left, through the space full of infinite and invisible routes; I do not want extraneous nuisances, harmful limits that impose me a path beforehand. I want to be entirely master of myself and not a slave of alien forces, insofar as human, are miserable and failing. – Víctor Català (Caterina Albert), Insubmissió (1947)

(Trans. A. B. Redondo-Campillos)

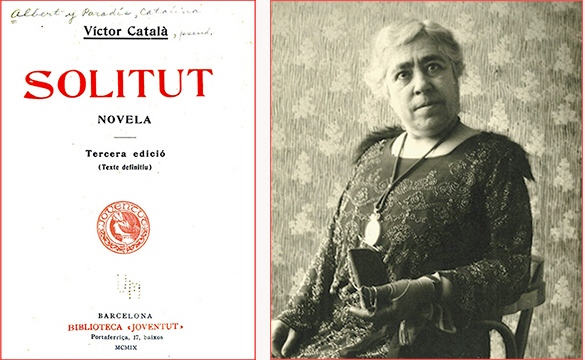

Víctor Català was a Catalan modernist literature novelist, storyteller, playwright, and poet. But Víctor Català was also Caterina Albert i Paradís (L’Escala, Girona, 1869–1966), an extraordinary talented woman writer forced to write under a male pen name. Caterina Albert decided to make herself known as Víctor Català after the publication of the monologue La infanticida (The Infanticide), for which Albert not only received the first prize in the 1898 Jocs Florals literary contest, but also an enormous backlash after the jury knew that the author was a woman. Amid the Catalan intellectual and bourgeois society of the late 19th century, Caterina Albert questions maternity as the main purpose of womanhood in the most dramatic and violent way. Víctor Català/Caterina Albert was probably the first unconscious feminist of Catalan literature.

In her magnum opus, Solitut (1905) or Solitud, first a serialized novel in the literary magazine Joventut and published later as a book, the writer follows the spiritual and life journey of Mila, a woman that moves to a remote rural environment, with a practically absent husband. In an extremely rough landscape — where the mountain becomes another character in the novel and part of Mila herself — she encounters her own sensuality, the guilt provoked by her sexual desire towards a shepherd, the unspeakable brutality of the few people living around her, and the absolute solitude. Far from being weakened because of all of these factors, Mila finds the necessary strength to get by and, finally, makes a life-changing decision.

It is 1905 and Caterina Albert depicts through Mila in Solitud the overly harsh women’s situation in a male rural society. Its novelty lies in that the writer provides the main character with the determination to overcome her disgrace. Mila transgresses the patriarchy system and takes control of her own life, and Caterina Albert transgresses the rules of a male literary society and writes whatever she wants to write. With Solitud the recognition of Víctor Català as a brilliant writer was unanimous: “the most sensational event ever seen in modern Catalan literature” in the words of critic Manuel de Montoliu (introduction to Víctor Català’s Obres Completes, Barcelona: Selecta, 1951).

Despite her success, Caterina Albert was considered a threat to the Noucentisme literary movement, due to her opposition to the group’s ideological agenda. After the publication of Solitud, Víctor Català published her second and last novel, Un film (3.000 metres) in 1926 and rather sporadically, some collections of short stories up to 1944. The author retired from the literary activity and died in her hometown, L’Escala, after having decided to spend the last 10 years of her life in bed.

Contribution by Ana-Belén Redondo-Campillos

Lecturer, Department of Spanish & Portuguese

Title: Solitut

Title in English: Solitude

Author: Víctor Català (pseudonym for Caterina Albert i Paradís), 1869-1966

Imprint: Barcelona : Biblioteca Joventut, 1909.

Edition: 3rd edition

Language: Catalan

Language Family: Indo-European, Romance

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (University of Michigan)

URL: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015029495648

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Serialized edition published across eight issues in April 2015 in Joventut: periódich catalanista: literatura, arts, ciencias. Barcelona : [publisher not identified], 1900-1906.

- Solitud. Barcelona : Edicions 62, 1979.

- Solitud. 1oth ed. Barcelona: Edicions de la Magrana, 1996.

- Solitud. 20th ed. Barcelona : Selecta, 1980. valoració crítica per Manuel de Montoliu.

- Solitude: A Novel. Columbia, La: Readers International, 1992. translated from the Catalan with a preface by David H. Rosenthal.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Danish

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

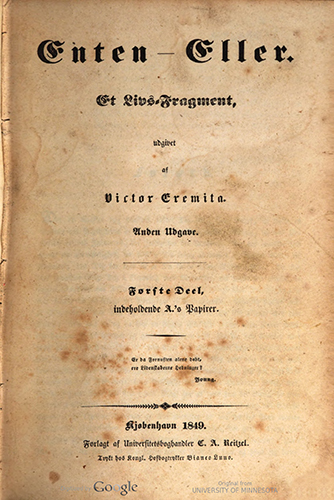

Although he had previously written a handful of articles, a book length review of a Hans Christian Andersen novel, and a magister dissertation on irony, the Danish philosopher, theologian and litterateur Søren Kierkegaard (1813–1855) considered Enten – Eller (Either/Or) to be the first work of his authorship proper. Under the pseudonym Victor Eremita, Kierkegaard published the two-volume novel with C. A. Reitzel in 1843. Kierkegaard published under pseudonyms so that the reader would not turn to him as an authority on how to interpret and live out the works. Henriette Wulff wrote from Copenhagen to H. C. Andersen in Germany, “Recently a book was published here with the title Either/Or! It is supposed to be quite strange, the first part full of Don Juanism, skepticism, et cetera, and the second part toned down and conciliating, ending with a sermon that is said to be quite excellent. The whole book has attracted much attention.”[1] By the standards of the small Danish book market, it sold well, and went into a second edition in 1849. The second edition is of especial interest because archival evidence indicates that Kierkegaard gave a gift copy of it to H. C. Andersen. This gesture can be seen as a rapprochement, since Kierkegaard’s 1838 review of Andersen’s Kun en Spillemand (Only a Fiddler) was quite scathing. Previously, Andersen had tried to show that there were no hard feelings by gifting Kierkegaard a copy of his Nye Eventyr (New fairytales), but Kierkegaard made no reply. Unfortunately, Andersen’s copy of the second edition of Enten – Eller is believed to be no longer extant. (In 2001, Niels Lillelund published a Nordic Noir novel entitled Den amerikanske samler [The American collector], which follows a bookstore owner’s pursuit of this priceless item.)

Enten – Eller has been translated into English, Spanish, Russian, and Chinese, as well as into a number of other languages. In addition to having online access to the second edition, the UC Berkeley Library has a hardcopy of the fourth edition in its holdings.

Danish is spoken by roughly six million people around the world. The Department of Scandinavian at UC Berkeley regularly offers courses in both the Danish language and in Danish literature in translation. The Danish language is taught by Senior Lecturer Karen Møller, and Danish literature is taught by Professor Karin Sanders. In the fall of 2018, Scandinavian 180, “The Works, Context, and Legacy of Søren Kierkegaard” introduced a group of students to Kierkegaard, the Danish Golden Age, and the author’s influence on twentieth-century philosophy and world literature. The course was taught by the author of this essay.

Contribution by Troy Smith

PhD Student, Department of Scandinavian

Sources consulted:

- Quoted in Joakim Garff, Søren Kierkegaard: A Biography, trans. Bruce H. Kirmmse (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2007), 216–17.

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Enten – Eller

Title in English: Either/Or

Author: Victor Eremita, pseudonym for Søren Kierkegaard (1813–1855)

Imprint: Kjøbenhavn, C.A. Reitzel, 1849.

Edition: 2nd edition

Language: Danish

Language Family: Indo-European, Germanic

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (University of Minnesota)

URL: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951d02153608j

Select print editions at Berkeley: Enten – eller. Et livs-fragment, udg. af Victor Eremita [pseud.]. 4. udg. Kjøbenhavn, C. A. Reitzel, 1878.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Armenian

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

At the request of the Librarian for the Armenian Studies, Liladhar Pendse, we are posting this entry on April 22nd in the memory of the victims of Armenian Genocide. The 24th of April is Armenian Genocide Remembrance Day. The resilience of the Armenian nation, language and culture exemplify a human desire to overcome destruction and create literary monuments.

Armenian scholar and official at the court of King Vramshapuh, Mesrop Mashtots (Մեսրոպ Մաշտոց) invented the Armenian alphabet in 405 CE. Today, Western Armenian is one of the two standardized forms of Modern Armenian, the other being Eastern Armenian. Until the early 20th century, various Western Armenian dialects were spoken in the Ottoman Empire, especially in the eastern regions of the empire historically populated by Armenians and which are known as Western Armenia. Western Armenian language is also spoken in France and in the diaspora of Armenians in the United States. On the other hand, Eastern Armenian is spoken in Armenia, Artsakh, Republic of Georgia, and in the Armenian community in Iran. The two Armenian standards together form a pluricentric language. Nevertheless, only Western Armenian is considered one of the endangered languages by the UNESCO.

In the late 1980s, a group of Bay Area Armenian-American visionaries decided to introduce the concept of Armenian Studies at one of the most renowned universities in the world — the University of California, Berkeley. Within a few years, under the leadership of the UC Berkeley Armenian Alumni, and thanks to the remarkable mobilization of the community and generosity of major donors, the William Saroyan Visiting Professorship in Modern Armenian Studies was established. Later the Krouzian Endowment, established in 1996, would provide this position with significant additional support. In the fall of 1998, the William Saroyan Visiting Professorship became a full-time position.

Professor Stephan Astourian was appointed Executive Director of the Armenian Studies Program and Assistant Adjunct Professor of History in July 2002. The William Saroyan position was no longer dependent on temporary appointments. Professor Astourian began to build the foundation of a full-fledged academic program focused on contemporary Armenian history, politics, language, and culture. The program now offers Armenian history Armenian that is further enriched by visiting scholars, academic conferences, symposia, and public speaking engagements organized or delivered by Professors Astourian and Douzjian.

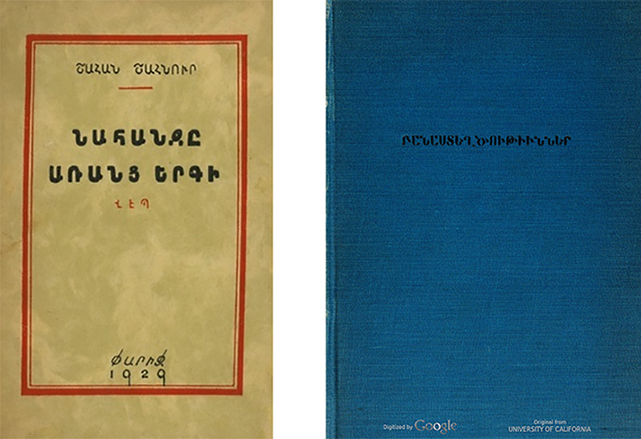

Shahan Shahnur’s Retreat Without Song was serialized in the Paris daily Haraj (Onward) before it was published as a novel in 1929. Set in Paris, the novel traces a tempestuous love story that provokes an identity crisis in the main character. While the interethnic romance between an Armenian man and a French woman drives the novel’s plot, its setting and characterization foreground the challenges Armenians faced after their exile from Istanbul, in the aftermath of the genocide. Upon publication, the novel enjoyed immediate success among readers; however, conservative critics, appalled by its violation of cultural taboos, labeled it pornographic. Today, precisely for its provocative treatment of religious values, romance, and diasporic life, Retreat Without Song rightfully occupies a place among the foundational texts of modern Western Armenian literature.

Hovhannes Tumanyan’s artful Eastern Armenian verse, unanimously loved by readers for over a century, presents cultural wisdom and a witty, critical perspective on socio-political dynamics. This collection includes two narrative poems that inspired operas: the tragic love story depicted in Anush served as the libretto for Armen Tigranyan’s homonymous opera whereas The Capture of Fort Temuk, a historical tale of political intrigue, was the basis for Alexander Spendiaryan’s Almast. Also notable in this collection, David of Sasun is based on the third cycle of the Armenian epic Daredevils of Sasun. A remarkable piece of literature, this epic circulated orally for almost a millennium until its first transcription in 1873, which in turn paved the way for studies and transcriptions of additional variants. Tumanyan’s verse adaptation of this epic, first published in 1904 and still widely read, bespeaks the poet’s mastery of folkloric style.

Contribution by Stephan Astourian & Myrna Douzjian

Faculty, Armenian Studies Program

Liladhar Pendse, Librarian for Armenian Studies, Doe Library

Title: Nahanjě aṛantsʻ ergi

Title in English: Retreat Without Song

Author: Shahnur, Shahan, 1903-1974

Imprint: Serialized for the daily newspaper Haraj =Haratch (Paris: Imp. Araxes, 1925-?).

Edition: Unknown

Language: Eastern Armenian

Language Family: Indo-European, Armenian

Source: Digital Library of Armenian Literature

URL: http://www.digilib.am/book/882/Երկեր%20թիւ

Print editions in Library:

- Sessiz ricat : resimli Ermeni tarihi = Nahanjě aṛantsʻ ergi = Silent Retreat = Retreat Without Song / Şahan Şahnur ; Ermeniceden çevirenler Maral Aktokmakyan, Artun Gebenlioğlu. Beyoğlu, İstanbul : Aras, 2016.

- Retreat Without Song / Shahan Shahnour ; translated from the Armenian and edited by Mischa Kudian. London : Mashtots Press, 1982.

Title: Banasteghtsutʻiwnner

Title in English: Selected Poems

Author: Tʻumanyan, Hovhannes, 1869-1923

Imprint: Kostandnupolis : Tpagrutʻiwn K. Kʻēshishean Ordi, 1922.

Edition: 1st edition

Language: Eastern Armenian

Language Family: Indo-European, Armenian

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (UCLA)

URL: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.l0081024747

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Spanish (Latin America)

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

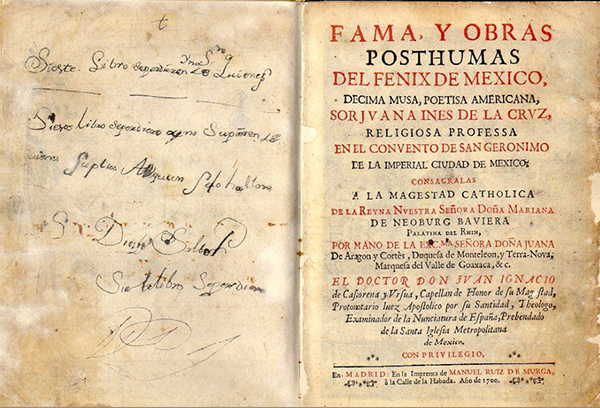

Nun, rebel, genius, poet, persecuted intellectual, and proto-feminist, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (Nepantla 1648-Mexico City 1695) was the most distinguished intellectual in the pre-Independence American colonies of Spain. She was called “Tenth Muse” in her own time and continues to inspire the popular and scholarly imagination. Generations of Mexican schoolchildren have memorized her satirical ballad “Hombres necios que acusáis / a la mujer sin razón… “ (You foolish men who cast all blame on women), and her portrait appears on the 200-peso note. Despite her status as an icon of Mexican culture, an annotated edition of her complete works was not published until the tercentenary of her birth in the mid-1950s, and the complexity of her poetry, prose, and theater was known only by reputation until the second wave of feminism brought scholarly attention to her work in the 1970s. Octavio Paz’s monumental study, Sor Juana, o, Las trampas de la fe (Sor Juana, or The Traps of Faith) appeared in 1982.

An intellectual prodigy brought to the viceregal court of New Spain in her teens, Sor Juana was largely self-taught. In 1669, she entered the convent of San Jerónimo in order to continue her studies. Although women were excluded from the study of theology and rhetoric, she wrote a brilliant critique of a renowned Portuguese cleric’s sermon, and was reprimanded by the Bishop of Puebla, who wrote under a female pseudonym. Sor Juana’s “Respuesta a sor Filotea” (1691, “Reply to Sister Philothea”) displayed her erudition in defense of her intellectual passion, arguing that St. Paul’s often-quoted admonition that women should keep silent in church (mulieres in ecclesia taceant), should not prohibit women’s pursuit of knowledge and instruction of young girls. Other significant works include secular and religious theater; philosophical poetry; passionate poems to the noblewomen who were her patrons; and villancicos, sets of songs she was commissioned to write for religious celebrations.

Sor Juana’s long epistemological poem, Primero sueño (First Dream) epitomizes the Creole appropriation of the Baroque and yet she weaves into her poetry and theater a recognition of the humanity of indigenous peoples. While her literary models were European and her poetry was first published in Spain, her works evince an American consciousness in the representation of the violence of the conquest in the loa to El divino Narciso (Divine Narcissus) and her use of Nahuatl in the villancicos.

Contribution by Emilie Bergmann

Professor, Department of Spanish & Portuguese

Title: Fama, y obras póstumas

Title in English: Homage and posthumous works

Author: Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (1648-1695)

Imprint: Madrid: Manuel Ruiz de Murga, 1700.

Edition: 1st

Language: Spanish (Latin America)

Language Family: Indo-European, Romance

Source: Universitätsbibliothek, Universität Bielefeld

URL: http://ds.ub.uni-bielefeld.de/viewer/image/1592397/1

Other online editions:

- Inundación castálida, de la única poetisa, musa décima, soror Juana Inés de la Cruz … (Madrid: Juan García Infanzón, 1689) and the first edition of Segundo volumen de las obras de soror Juana Inés de la Cruz (Sevilla: Tomás López de Haro, 1692).

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Critical and annotated editions of the first two volumes of Sor Juana’s work, Inundación Castálida (1689) and Segundo tomo (1693), as well as Fama, y obras póstumas and editions of complete and selected works are available in printed form in The Bancroft Library and the Main Stacks.

- Sor Juana’s complete works were published in four volumes: Obras completas, Alfonso Méndez Plancarte and Alberto G. Salcedo. Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1951-57. Many English translations of selected works of Sor Juana’s works are also in OskiCat including those of Alan S. Trueblood, Margaret Sayers Peden, Amanda Powell, and Edith Grossman.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

![The Languages of Berkeley [fan]](https://update.lib.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/fan_languages-450px.jpg)