“I was just one of thousands of people over the years who have done the little things necessary to create and to pass on personal narratives of the past.” —Mollie Appel-Turner

Introduction: Thoughts on the Production of Oral History and Its Importance

by Serena Ingalls, class of 2023

Like many of my student co-workers at the Oral History Center (OHC), I have recently graduated from UC Berkeley. Graduation from college is a major milestone, and I find myself looking back at all of my different experiences at Cal: classes, clubs, the pandemic, and my job as a student editor and researcher at the Oral History Center. My job in oral history in particular is a point of contemplation, as I’ve spent many hours in this role and it’s a unique experience that only a handful of other students can relate to. I find myself wondering, how has this job impacted me and my view of the world? How has my work in this role contributed to the field of history?

Before closing the UC Berkeley chapter in our lives and moving on to other post-grad interests, we as the student editors took the time to reflect upon our work at the Oral History Center and what it means to us. We hope that you’ll enjoy stepping into our world as student editors in oral history, just as we have enjoyed the experience of getting to know the many fascinating individuals in our oral history archive.

Editor’s note: Our team’s student editors serve critical functions in our oral history production, analyzing entire transcripts to write discursive tables of contents, entering interviewee comments, editing front matter, writing abstracts, and more. They do the work of professional editors and we would not be able to keep up our pace of interviews without them.

Mollie Appel-Turner: Oral History and Connection

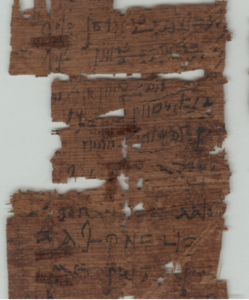

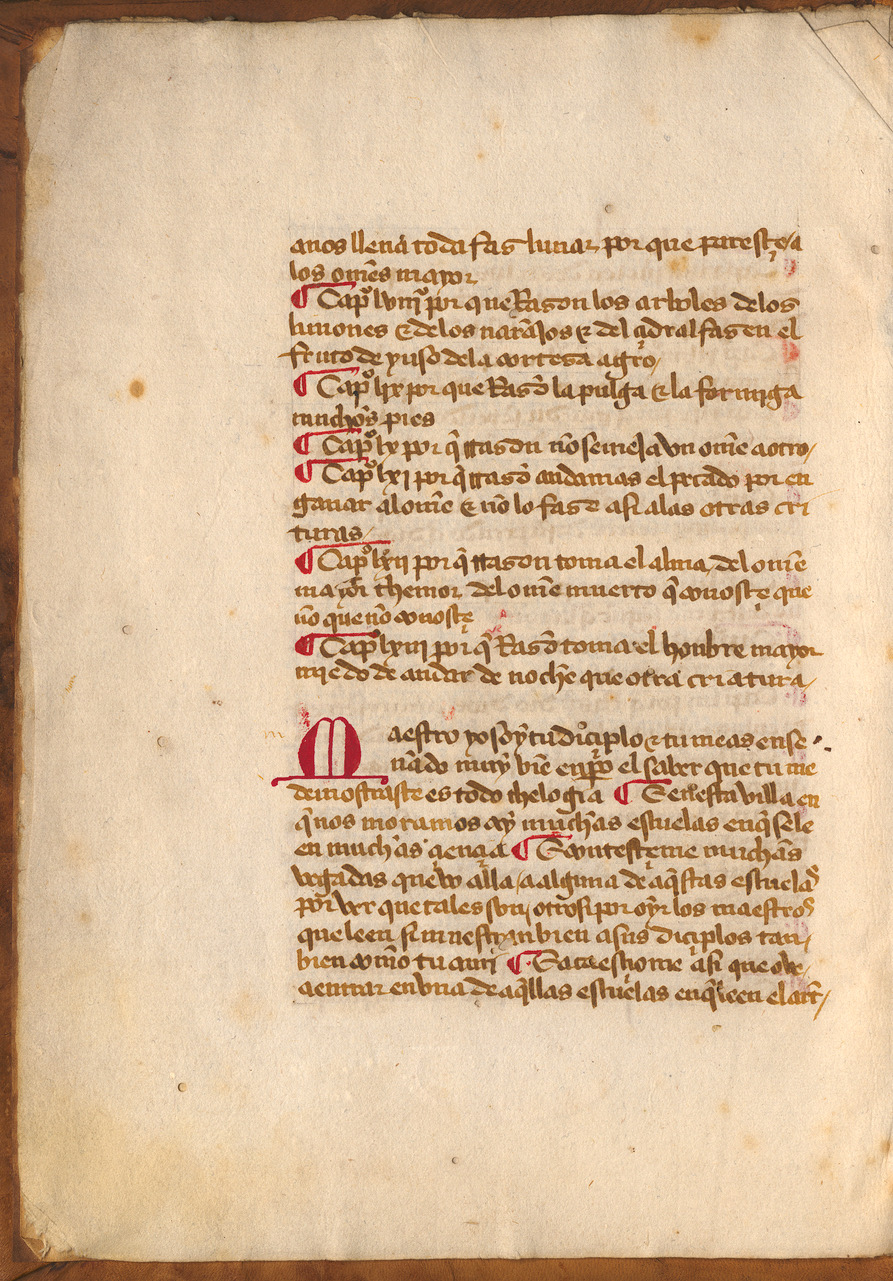

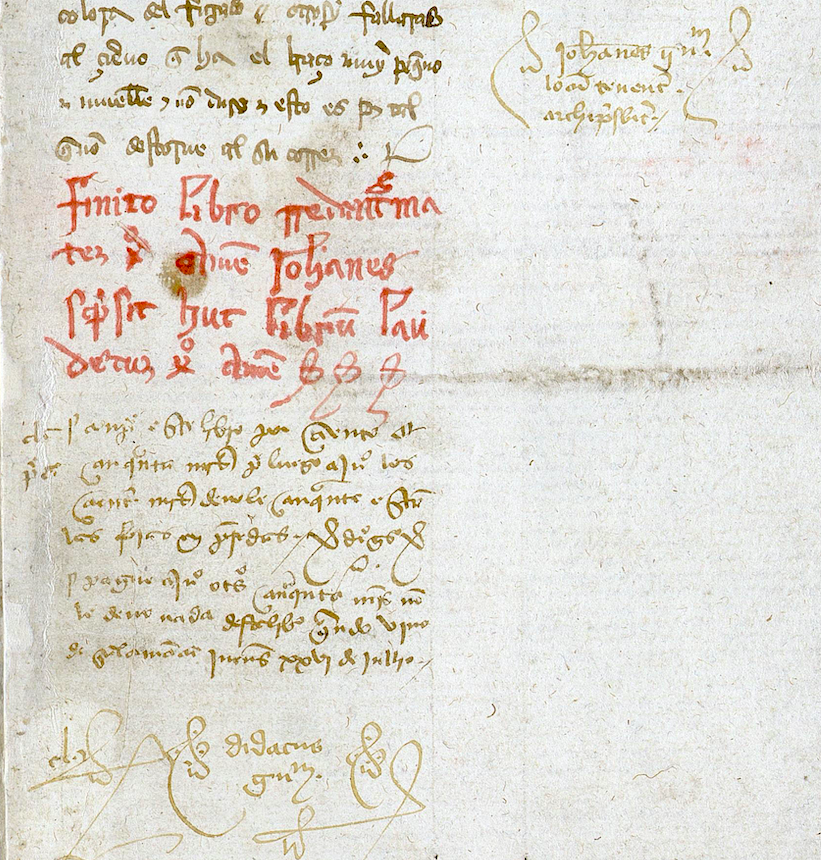

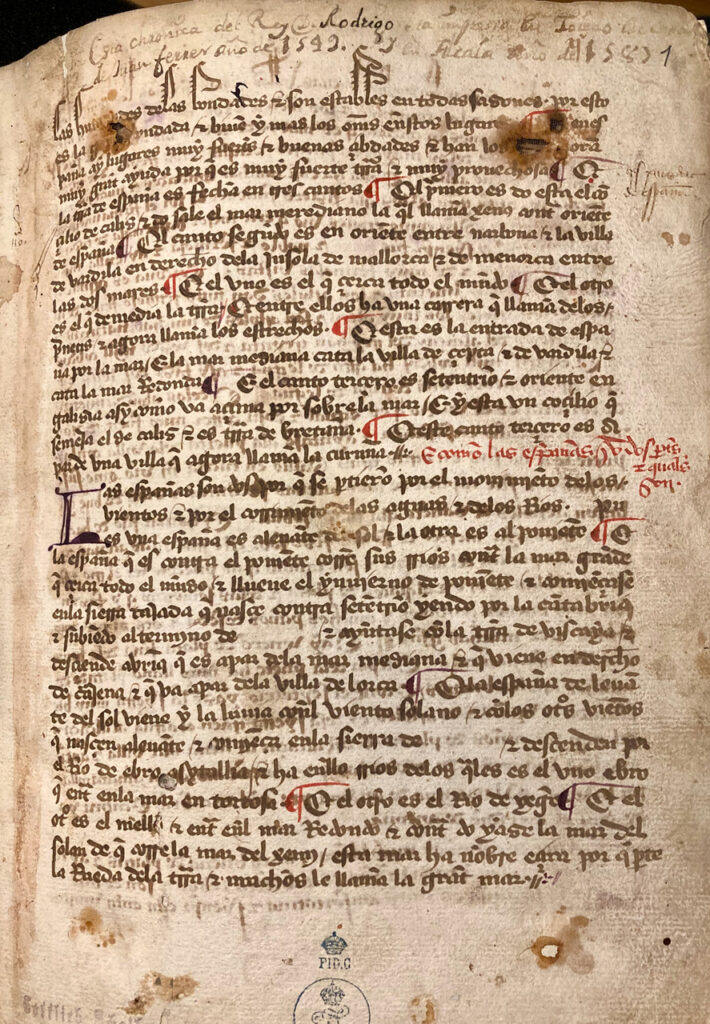

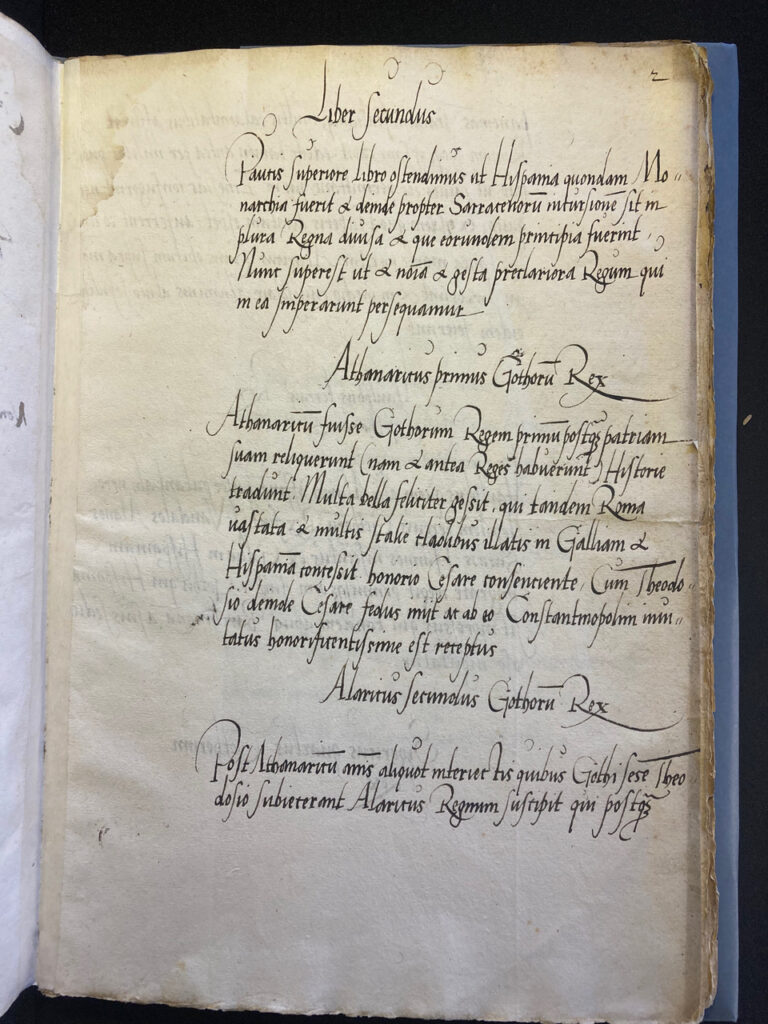

Working for the Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library while pursuing a history degree was both deeply rewarding and extremely unfamiliar. My area of interest when it comes to history has always been western medieval Europe. While there are plenty of sources from the era where people recount their life experiences, I always had an awareness of the massive separation—temporal, cultural, and physical—between myself and the speaker. At the Oral History Center, I was keenly aware that the work that I was doing on oral histories was with the ultimate goal of preserving knowledge for future generations. But for the time being, that gulf I was used to, which to me practically defined the work I did as history, was simply not present. In my time outside of work, I also spent a fair chunk of time reading people’s personal accounts. While these accounts differed in many ways from the oral histories that I worked on, as time passed, I came to see these different kinds of personal accounts as reflections of one another. I would frequently stop in the middle of my shift, cursor blinking next to a spelling error, and think about how I was just one of thousands of people over the years who have done the little things necessary to create and to pass on personal narratives of the past. The immediacy, and modernity of the accounts that I worked on at the Oral History Center, rather than widening the distance I felt between me and the medieval people I studied, made me feel closer to them in a way that I did not expect.

Mollie Appel-Turner joined the UC Berkeley Oral History Center as a student editor in fall 2021. She recently graduated with a degree in history with a concentration in medieval history.

Shannon White: Oral History and Inspiration

In my time at the Oral History Center, I have worked on and witnessed the publication of interviews from an innumerable variety of narrators, including artists, writers, curators, academics, conservationists, and otherwise “ordinary” people with extraordinary stories to tell. I recall the first oral history I worked on upon joining the Center: Thomas Gaehtgens, former director of the Getty Research Institute, whose interview was not only incredibly detailed but also quite interesting to read. More recently, I have helped edit interviews from the Chicana/o Studies Oral History Project, the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project, and the California State Archives State Government Oral History Program.

As a member of the OHC’s editorial team, most of my work is behind the scenes and prior to publication. I see these interviews at almost every stage in production. By the time an oral history transcript is finalized, I have generally read through it in its entirety several times and am quite familiar with the contents; as such, I interact with oral history at multiple levels. This experience has ultimately helped form and maintain my view of oral history as an inherently dynamic, interactive record—a form of living history.

The final oral history is a labor of many people to produce, with several rounds of edits and review that heavily draw from the narrator’s own input, and as such possesses a strong sense of the narrator’s personal style: how they speak, what they consider important or even essential for understanding their stories, their sense of humor, and what elements of the initial oral interview they would prefer to keep private.

The result is a distinctively humanizing portrayal of the narrator that arises from the nature of oral history as a lightly edited, audio-based interview format. The reliance on the “oral” aspect of oral history means that, bar serious editing, the published transcripts of interviews from the OHC tend to preserve a great deal of the tone of the original audio recording, including quirks of speech unique to each narrator. My personal favorite detail is always the bracketed notes included by the transcriber to indicate when someone is laughing, a phenomenon that often accompanies the conversation between interviewer and narrator and, in my opinion, highlights the deeply personal nature of these interviews.

By sheer virtue of the volume of in-progress oral histories I interact with, I find that in time they become almost a part of you—there are so many narrators whose words and stories I remember, and whose work I have actively sought out after encountering their oral histories. For example, I became interested in Bay Area arts institutions after reading the interview of a San Francisco Opera board member; my own undergraduate research has been informed in no small part by border theory, a concept I was first introduced to by the narrators of the Chicana/o Studies Oral History Project; and my work on the oral histories of California politicians has contributed to my awareness of the history of the state’s politics. Oral history is intimate and alive, and its existence has the unique ability to inform and inspire those who engage with it.

Shannon White is a recent UC Berkeley graduate in the Department of Ancient Greek and Roman Studies. They were an undergraduate research apprentice in the Nemea Center under Dr. Kim Shelton and a member of the editing staff for the Berkeley Undergraduate Journal of Classics. Shannon worked as an editorial assistant for the Oral History Center.

Serena Ingalls: Oral History and Insight

Before working at the Oral History Center as a student editorial and research assistant, my interactions with oral history were limited. As a history major, it was a topic occasionally mentioned in my classes at Cal. I could understand the value in oral history as a way of filling in gaps in the historical record and giving a voice to those who were excluded from the written record. After I began my work with the OHC, however, I gained a new appreciation for oral history. This change in perspective came after seeing firsthand the immense effort that goes into producing oral histories to be shared with the public, and from reading the oral histories in our archive.

At the Oral History Center, I’ve worked in two roles. One of my roles is as a research assistant. In order to promote our archive and share our interviews with the public, we post on social media about relevant historical anniversaries (25th, 50th, 75th, 100th). I research these anniversaries and then search the archive to see if we have content that references these historical events. It’s surprising how many specific events are mentioned by interviewees, so I never discount an event without checking first with the archive. If there is one event that is very historically significant and has several interviews that reference it, sometimes I’ll write an article on the subject for the OHC. My other role is as an editorial assistant. Editorial assistants are part of the process of readying an oral history for publication. Student editorial assistants have a range of responsibilities during the editorial process which include inputting corrections from narrators, writing the table of contents, and more. Editing the oral history is a collaborative process, and it can take months or even years before an oral history is fully ready for publication. Once an oral history is completed and shared with the public, all who have worked on a particular oral history know the narrator inside and out.

The OHC has an enormous archive of interviews with narrators who have incredible insight on the history of California and beyond. Their voices provide knowledge, but more critically, they add life to these historical periods. The interviews are at times surprising, heartbreaking, and even funny, and no two interviewees have the same story. Each interview is a unique combination of the mundane and the extraordinary, just like the life of any person.

“Each interview is a unique combination of the mundane and the extraordinary, just like the life of any person.” —Serena Ingalls

Serena Ingalls recently graduated UC Berkeley with majors in history and French. She is an editorial and research assistant for the Oral History Center. Serena came up with the idea for an article about what it’s like to work on oral histories when she worked on an article about the seventy-fifth anniversary of the tape recorder.

William Cooke: Oral History and Truth

A few short months ago, I graduated from UC Berkeley. I have completed 12 political science courses; written dozens of sports articles for Berkeley’s independent student newspaper, The Daily Californian; struggled my way through one too many required science classes; and penned more than a few essays en route to a minor in history.

As a journalist and student, determining and advancing truth was at the heart of everything I did. For example, in order to make a sound political science argument about the role of agency in a democracy, I could not reinvent what Harriet Jacobs wrote in her autobiography, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Desiderius Erasmus had something specific to say about tyranny. What was it, exactly? Did Cal’s football team run or pass the ball more often on third down? If the United States federal government really did assume a different position towards organized labor after World War II, what evidence supports that claim?

The answers to my own questions, or the questions my professors asked of me, had to be completely truthful. I certainly couldn’t say that I didn’t have an answer to an essay prompt.

Oral history is a little bit different. When I first began working here last year, I couldn’t help but be skeptical. An interviewee in her eighties cannot with absolute accuracy remember her childhood years during the Great Depression, or her immediate reaction to the assassination of President Kennedy. Memory fails people all the time. A story might be true on the whole, I thought to myself, but the details might not. And what use was the answer “I don’t know?” That might be the truth, but what good is an oral history in which there are gaps?

In short, how could a researcher possibly find use in an incomplete, possibly inaccurate story told by someone fifty years after the fact?

Of course, these questions are not on my mind as I write a table of contents or fix formatting issues on a transcript. My work can be tedious at times. As someone whose mind likes to stay busy, I don’t mind. But every now and then I will stop and think critically about what I’m reading and how it relates to my role as a student, journalist, and assistant at the Oral History Center; namely, promoting truth.

I soon came to terms with the fact that oral histories cannot be totally accurate and that in an important way they are true. While the historian attempts to explain how people in the past saw themselves, their situation or others in very broad terms, the oral history provides insight into how a creator of history currently thinks of her past self, a valuable perspective for social scientists of all stripes. An interviewee might have felt more anxious than nervous at a certain moment in history, but how he remembers the past is also an important part of history. What good is there in knowing the true happenings if we do not know how the living, breathing makers of history think about what happened?

And for that reason, I have come to realize that oral history isn’t impure, or less true. I do still read the oral histories I work on with a wary eye. But I don’t worry about their truthfulness like I first did back in the spring of 2022. Instead, each time I complete my portion of a project, I feel a sense of gratification for having helped keep history alive. Because true history is not a fixed thing. It lives in the minds of everyone who has experienced it.

William Cooke recently graduated UC Berkeley with a major in political science and minor in history. In addition to working as a student editor for the Oral History Center, he is a reporter in the Sports department at UC Berkeley’s independent student newspaper, The Daily Californian.

Related Works

Serena Ingalls, Saving the Spoken Word: Audio Recording Devices in Oral History

Mollie Appel-Turner, Shirley Chisholm, Women Political Leaders, and the Oral History Center collection

William Cooke, Title IX in Practice: How Title IX Affected Women’s Athletics at UC Berkeley and Beyond and Heavy hitters: the modern era of athletics management at UC Berkeley

Shannon White, “I take this obligation freely:” Recalling UC Berkeley’s loyalty oath controversy

Jill Schlessinger, editor, A peaceful silence: Berkeley undergrads reflect on remote employment during the pandemic

About the Oral History Center

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying perspectives, experiences, pursuits, and backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. You can find our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.