The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

Azerbaijani (Azeri)

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

Azerbaijani or Azeri is the term that is used interchangeably for the language throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. It is also known as Azerbaijani Turkish and retains most of the traditional grammatical endings of the pre-Republican era Turkish language that was spoken in the Ottoman Empire. However, in a certain sense, it is also influenced heavily by the Persian vocabulary. The language is currently spoken in the Republic of Azerbaijan that was a part of the Czarist Empire in the 19th century as well as in Southern Azerbaijan that is the part of modern-day Iran. In the Republic of Azerbaijan, the language script was changed several times. Currently the Latin script is used. The Iranian Azerbaijan continues to use Arabo-Persian script.

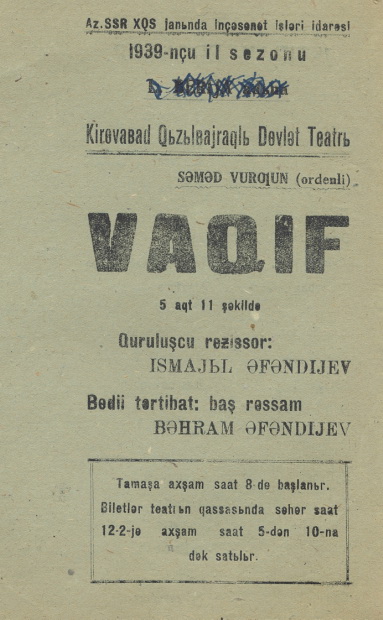

Samad Vurgun was a well-known Azerbaijani poet and playwright. The first work of Vurgun—the poem “Address to Youth”—was published in 1925 in the Tbilisi newspaper New Thought. Today every Azerbaijani schoolchild is familiar with his poetry. It is often set to music and performed by leading Azerbaijani artists. Featured in this entry is the play Vagif written in 1937 and which pays homage to the 18th-century Azerbaijani poet Molla Panah Vagif.

During his youth, Vurgun lived through the tough years of World War II. This challenging period had a very significant impact on his poetry, which was a real weapon against the enemy in that difficult time. He wrote over 60 poems on the theme of the Great Patriotic War. It was not an easy task, but in his works, the young poet managed to inspire an optimistic mood amongst the people, who were suffering from the hardship of war.

He was calling on people to be patient and hardworking to attain victory. Vurgun’s popularity grew during the propaganda campaign—leaflets with his creation “Ukrainian partisans” were dropped from planes over local forests to maintain the high spirit of the guerrilla fighters.

His poem “Parting Mother” was highly appreciated as the best anti-war work during a contest held in the US in 1943. It was published in New York and distributed to military personnel after it was selected among the best 20 poems of world literature about the war.

During World War II, Vurgun created poems dedicated to the deeds of Azerbaijanis in the fight against fascism. In the poems “Nurse”, “Bearer”, “The story of the old soldier”, “Brave Falcon”, and “Unnamed Hero”, he describes the selfless struggle against the invaders, the heroism of Azerbaijani soldiers and their contribution to the liberation of people from fascism. Due to his patriotism and unique talent, Samad Vurgun became a poet of the nation.

In 1943, Vurgun was awarded the title of Honorary Artist of Azerbaijan SSR. Two years later he was elected to the Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences. His works have been translated into many foreign languages. For many years, he headed the Azerbaijan Union of Writers, was repeatedly elected a deputy of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR and Azerbaijan and was awarded many orders and medals. His early lyric poems were published only after his death, in a compilation called “Chichek” (“Flower”).

Living in the era of a communist dictatorship, Vurgun had to praise the regime in his works, but in spite of this, the creativity of Vurgun, the restrained style of his poems had a tremendous impact on the development of the Azerbaijani poetry. Samad Vurugn died in May of 1956 and is buried in the Alley of the Heroes in Baku.

The Azerbaijani Studies collections in the UC Berkeley Library represent the current research interests of our faculty and students. One of the well-known scholars of Caucasus Studies, Professor Stephan H. Astourian, interrogates the historical realities of Caucasus, Armenia, and Azerbaijan in the context of the Armenian Genocide. The Azerbaijani collections are also supported through the donations of books by the Azerbaijan Cultural Society of Northern California. One prominent mathematics professor of Azerbaijani descent was Lotfi A. Zadeh. The focus of current collections on Azerbaijan revolves around the history of Azerbaijan and Caucasus, Armenian Genocide and the Frozen conflict of Artsakh/Nagorno-Karabakh.

Contribution by Liladhar Pendse

Librarian for East European and Central Asian Studies, Doe Library

Source consulted:

Gadimova, Nazrin. “Samad Vurgun: A Poet With Pen as Sharp as Weapon,”AzerNews (May 28, 2013), (accessed 5/1/20)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: “Vagif” in Səməd Vurğun : Seçilmiş əsərləri.

Title in English:

Author: Vurghun, Sămăd, 1906-1956.

Imprint: Bakı : “Şərq-Qərb”, 2005.

Edition: n/a

Language: Azerbaijani (Azeri)

Language Family: Turkic

Source: Sabunchu District Central Library, Central Libraries of Azerbaijan

URL: http://sabunchu.cls.az/front/files/libraries/54/books/831431433401352.pdf

Other online editions:

- Vurghun, Sămăd, 1906-1956. Избранные сочинения в двух томах: перевод с азербайджанского. Translated into Russian by Pavel Antokolʹskiĭ. Moskva: Gosizdatel’stvo khud.literatury, 1958.

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Vagif ; Mughan / Sămăd Vurghun. Baky: Gănjlik, 1973.

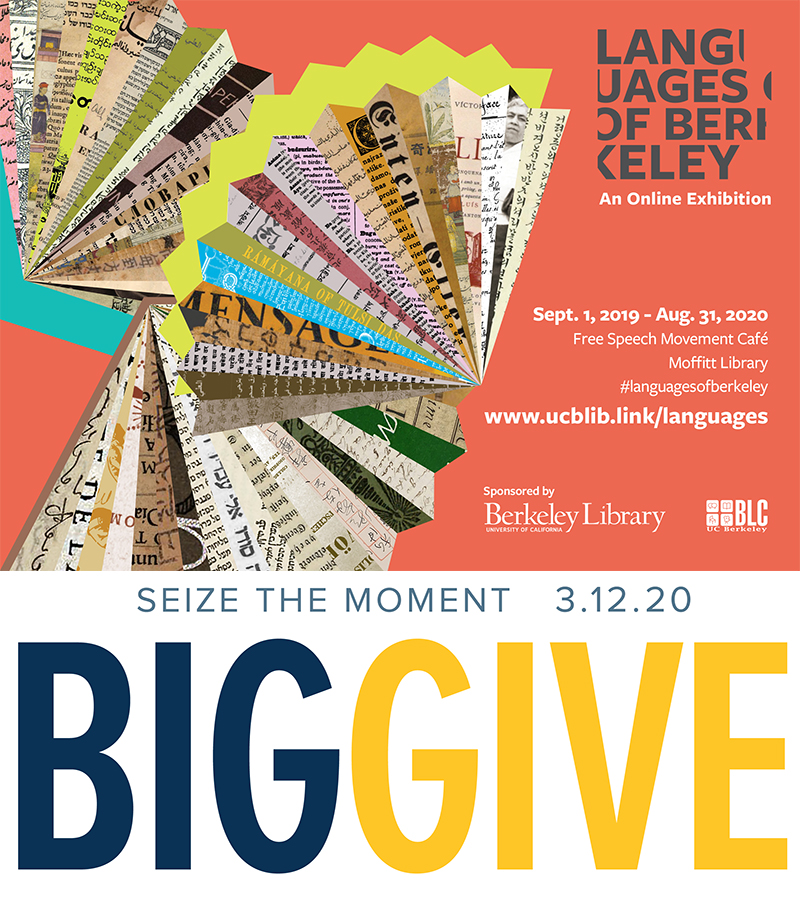

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

The Promise of Multilingualism by Judith Butler

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

“If we were only to work in English, we would misunderstand our world.

Monolingualism keeps us parochial even if the language we speak

has achieved global dominance.”

In her keynote lecture on Feb. 5 for the exhibit reception for The Languages of Berkeley, Judith Butler said that “At UC Berkeley and in this Library in particular, in language courses and in literature and history courses, students and faculty alike understand themselves to be part of an ongoing multilingual experiment—one that brings with it different histories and cultures, different ways of understanding the social world.” A world-renowned philosopher, gender theorist, and political activist, Butler is best known for her book Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (1990), and its sequel, Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of ‘Sex’ (1993), which have both been translated into more than twenty languages. Her most recent book is The Force on Nonviolence: An Ethico-Political Bind (2020). She has taught at Cal for 27 years in the Department of Comparative Literature and in the Program of Critical Theory, where she is Maxine Elliot Professor. Among her achievements, she is currently the 2020 president of the Modern Language Association, in which she is, in the words of Professor Rick Kern, “the lead advocate for languages in the United States.”

Butler’s lecture, “The Promise of Multilingualism,” eloquently put into words the inspiration for the exhibition itself. “In learning another language, we practice humility in an effort to gain knowledge and to live in a broader world—one that exceeds the national boundaries that too often divide us,” she said. “The passage through humility gives us greater capacity to live and think in a multilingual world, to shift from one way of knowing to another.” Her entrancing talk that winter evening in the iconic Morrison Library—which followed nine short readings by faculty, students, and librarians in different languages—echoed and expanded on some of the ideas in Who Sings the Nation-State?: Language, Politics, Belonging which she co-wrote with Gayatri Spivak in 2007.

At Berkeley, and in literature, history, and philosophy departments especially, “multilingualism is our location and it means that we never assume one language holds the truth over any other,” she said. By learning and working in other languages, she posited, we experience both dislocation and an enriching humility finding ourselves less capable in another language than the primary one that we speak. For some of us, for whom English is a first language, we have a promising experience that productively challenges the notion that English is at the center of the world. “Each and everyone of us speaks a language that is foreign to someone else,” she affirmed. “At least here, at least potentially what we call ‘the foreign’ is actually the medium in which we live together, the enigmatic basis of our worldly connection with one another.”

The Arts & Humanities Division of the UC Berkeley Library and the Berkeley Language Center (BLC) hosted the reception for the online exhibition. University Librarian Jeff MacKie-Mason gave introductory remarks, and Rick Kern, director of the BLC and professor in the Department of French, introduced the keynote speaker. Romance Languages Librarian Claude Potts, who is the lead curator for the exhibition, involving more than 40 contributors, moderated the event. Four of those who read short texts in their original languages also contributed to the online sequential exhibit, which launched in February 2019 and will reach completion this summer, with approximately 70 entries representing most of the languages that are currently taught and used in research at Berkeley.

Virginia Shih for Vietnamese (South/Southeast Asia Library) – 13:40

Curator for the Southeast Asia Collection

Ahmad Diab for Arabic (Department of Near Eastern Studies) – 17:08

Assistant Professor

Yael Chaver for Yiddish (Department of German) – 23:50

Lecturer in Yiddish

Jeroen Dewulf for Dutch (Department of German and Dutch Studies Program) – 31:30

Director, Institute of European Studies

Interim Director, Institute of International Studies

Queen Beatrix Professor

Sam Mchombo for Chichewa (African American Studies) – 38:58

Associate Professor

Deborah Rudolph for Chinese (C.V. Starr East Asian Library) – 48:31

Curator

Marinor Balouzian and Natalie Simonian for Armenian (Armenian Studies Program) – 53:21

Undergraduate Students

Emilie Bergmann for Spanish (Department of Spanish & Portuguese) – 58:19

Professor

Robert Goldman for Sanskrit (Department of South and Southeast Asian Studies) – 1:07:05

Catherine and William L. Magistretti Distinguished Professor

See also the Library News story “Want to explore a language? At Berkeley, the possibilities are (nearly) limitless.”

Or the blog post “We All Speak a Foreign Language to Someone” by Caitlyn Jordan for the Townsend Center for the Humanities.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

www.ucblib.link/languages

Syriac

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

—One of Socrates’ disciples asked him, “How come I never see in you

any sign of sorrow?” Socrates replied: “Because I don’t possess anything

that I would grieve over if it got lost!”

—Another philosopher was asked: “What is it that would benefit most

people?” He replied: “The death of an evil ruler.”

—A man saw in a dream that he was frying pieces of dung. So he went to

a dream-interpreter to get an explanation of the dream. The dream-

interpreter said to him, “If you give me a zuza [a small coin], I will

interpret it for you.” The man replied, “If I had a zuza, I would buy some

fish with it and fry them, instead of frying pieces of dung!”

—A woman asked her neighbor, “How come it is permitted for a man to

buy a hand-maiden for himself, and to sleep with her, and do whatever he

wants, while it is not permitted for a woman to do any of these things, at

least in public?” The neighbor said to her, “It is because kings, judges, and

law-makers have all been men, and so have been able to justify their

actions and oppress women.”

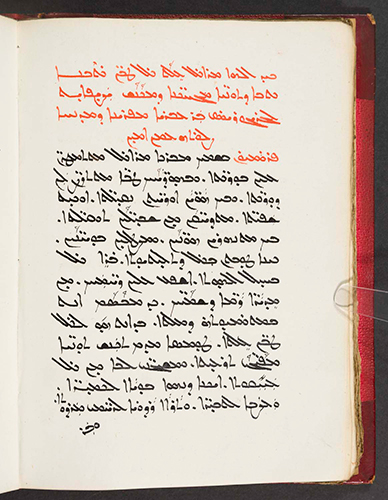

These four anecdotes come from a work entitled The Book of Entertaining Stories, written in the Syriac language. Syriac is a member of the Aramaic branch of the Semitic languages. It developed as an independent language around the city of Edessa, today’s Shanliurfa, in southeastern Turkey. The first Syriac inscription dates to the year 6 AD. Shanliurfa became a center of early Christianity, and over the next thousand years a wealth of literature was written in Syriac, including historical annals, scientific texts, medical manuals, philosophical and theological tractates, religious poetry, and Bible translations and commentaries. Because of the richness of theological literature written in Syriac, it is sometimes called the “third language of Christianity,” after Greek and Latin. Much of this knowledge still exists only in manuscript form, awaiting study.

The earliest Syriac texts are in a recognizably Aramaic form of the Semitic alphabet, which was originally developed by the Phoenicians. As with all Semitic alphabets, it reads from right to left. As time went by, it took on its own distinctive form, appearing in three distinct “fonts.” The manuscript page reproduced here is in the “West Syriac” font. The original Phoenician alphabet indicated only consonants, not vowels, but Syriac developed different ways to indicate vowels. These take the form of small signs written either above or below the consonants. These are however only used sporadically. In the page illustrated here, the vowel marks were added by a different scribe than the one who wrote the consonantal text.

With the Arab-Muslim conquests of the Near East, starting in the seventh century AD, Syriac was gradually replaced by Arabic as a spoken language. By about 1300 AD, there were probably very few native speakers of Syriac. However, it continued in use as a written language, right up to the present day, in fits and starts. Moreover, Syriac is still used in the liturgy of several Christian churches mostly in the Middle East, notably the Syrian Orthodox Church and the Syrian Catholic Church.

In scattered pockets in today’s Middle East, particularly in Iraq and Syria, Aramaic survives as a spoken language. These languages/dialects are known by a bewildering number of names, including “Neo-Syriac.” It is difficult to say, however, if any of them are direct continuations of classical Syriac, or of some similar Aramaic dialects.

The illustration featured here is the first page of a manuscript of The Book of Entertaining Stories, which was written about the year 1280 AD. The manuscript (dating to the 19th century) is now in Leeds, England, and is used here by permission. The author of the Book was one Gregory Bar-Hebraeus (1226-1286 AD). Bar-Hebraeus was born in a village called Ebra, in modern-day eastern Turkey. In the course of a long priestly career, he ended up as second-in-command of the Syrian Orthodox Church. He was a prolific writer: a recent bio-biography of his works in both manuscript and printed editions extends to over 500 pages. For this book, Bar-Hebraeus gathered edifying stories and anecdotes from many different cultures and languages, and turned them into Syriac. He wrote this work towards the end of his life, when he had intimations of his demise, “to wash away grief from the heart” as a “consolation to those who are sad.” As illustrated above, many of these stories are quite amusing, even today. Other anecdotes invoke wise men of ancient Persia, doctors, poor people, and more. There are a surprising number of stories involving “demoniacs,” that is, people possessed by demons; these are most probably stories involving the mentally ill. This work of his is probably the only work of Syriac literature known to non-specialists. It has been translated into many languages, including Czech, Ukrainian, and Malayalam. It was edited in 1897 by E.A. Wallis Budge: The Laughable Stories Collected by Mar Gregory John Bar-Hebraeus, on the basis of two manuscripts.

Syriac studies have traditionally flourished in Europe, less so in the United States. In the last thirty or so years, Syriac studies both here and abroad have undergone something of a Renaissance. In 1992, in New Jersey, an institution called The Syriac Institute in English and Beth Mardutho (“House of Learning”) in Syriac was founded, with the goal of “the establishment of a Syriac studies center affiliated with leading universities that globalizes Syriac studies through the Internet.” Some four years ago, after a long hiatus, Syriac was again taught at Cal, within the larger context of Aramaic studies.

Contribution by John L. Hayes,

Lecturer, Department of Near Eastern Studies

Sources consulted:

- Hidemi Takahashi. Barhebraeus: A Bio-Bibliography. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. 2005.

- E.A. Wallis Budge. The Laughable Stories Collected by Mar Gregory John Bar-Hebraeus. London: Luzac and Co. 1897.

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: The Laughable Stories Collected by Mâr Gregory John Bar Hebræus

Author: Gregory Bar-Hebraeus (1226-1286 AD), the Syriac text edited with an English translation by E. A. Wallis Budge.

Imprint: London: Luzac and co., 1897.

Language: Syriac

Language Family: Afro-Asiatic, Semitic, Northwest Semitic

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library

URL: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/001854249

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Judeo-Persian

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

Jews have lived among Persian speakers, and spoken Persian dialects, since at least the period of the Achaemenid Empire (550 BC–330 BCE). Influences from Iranian linguistic and literary traditions are evident in post-exilic books of the Hebrew Bible and apocrypha, in addition to Second Temple and classical rabbinic traditions. The rise of Persian literature written by Jews in Hebrew script coincided with the New Persian literary renaissance that began in the eighth century CE. Today, Jewish communities with roots in Iran, Central Asia, the Caucasus, and elsewhere continue to write and speak in dialects of Persian, but these have yet to receive a degree of popular or scholarly consideration commensurate with their status as historically-significant and enduring Jewish languages.

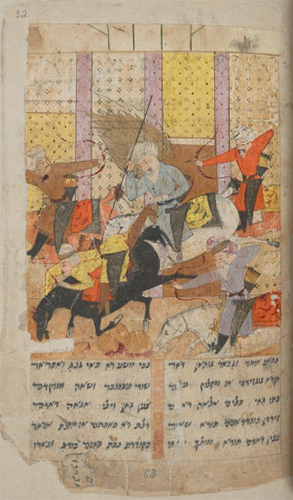

The Fath-Nāmeh or “Book of Conquests” is a versified rendition of stories from the books of Joshua, Judges, Ruth, I Samuel, and II Samuel in Judeo-Persian (New Persian written with Hebrew characters) by the poet ‘Imrāni. ‘Imrāni lived in Isfahan and Kashan during the late Timurid and early Safavid periods (15th/16th century CE) and composed in the masnavī poetic style—in rhyming couplets following a meter of eleven syllables—comparable in form to the Masnavi-e Ma’navi (“Spiritual Couplets”) of the 13th-century poet Rumi. Like similar works by his predecessor, Mowlānā Shāhin-i Shirāzi, and his successors, Aḥaron ben Mashiaḥ and Khwājaj Bukhārā’ī, the Fatḥ-Nāmah is an example of Jewish ‘rewritten bible’ in the Iranian epic mode exemplified by the Shāh-Nāmeh (“Book of Kings”) of Ferdowsi (10th/11th century). Rhetorical, symbolic, and thematic elements also recall the Leili o Majnun (“Layla and Majnun”) of Nizami Ganjavi (12th/13th century) and the poetry of Hafez (14th century).

While he employs recognizably Islamic terminology such as tahlīl (“praise” of God, usually referring to the first portion of the Muslim shahādah formula) and tawḥīd (“oneness” of God), ‘Imrāni’s frequent inclusion of Hebrew words—sometimes with Persian endings e.g. kohen-ān—points to his Jewish background, as do his choices of source material. Other works by ‘Imrāni include (1) the Sufi-influenced Ganj-Nāmeh (“Book of Treasure”), a versified rendering of the first four chapters of the Mishnaic tractate Avot; (2) the Ḥanukkah-Nāmeh or Ẓafar-Nāmeh (“Book of Victory”), which relates the Maccabean narrative; (3) midrashic retellings of the ten Jewish sages martyred during the reign of Hadrian, of the seven sons of Hannah martyred during the Hasmonean revolt, and of the sacrifice of Isaac; (4) a treatise based on Maimonides’ Thirteen Principles; and (5) poetic works on themes of moral, religious, and practical instruction.

The Fath-Nāmeh also refers to stock themes and characters from the Iranian epic tradition—such as the equation of the reign of the biblical king Saul to that of the Pishdadian ruler Jamshid and the use of symbolic imagery from Ferdowsi’s Shāh-Nāmeh. Passages that relate didactic advice reflect the Pahlavi andarz (“instruction”) traditions associated with Ādurbād ī Mahrspandān and other Sasanian-era Zoroastrian figures. Accompanying illustrations, as Orit Carmeli observes, reflect styles known from other Persian manuscripts of the Safavid and early Qajar periods. Vera Basch Moreen’s English translation constitutes a significant advance in rendering such material for non-specialists, spotlighting the richness of the Judeo-Persian tradition within the broader oeuvre of Jewish literature.

Delve into Judeo-Persian:

- Read about Judeo-Persian at the Jewish Languages Project and in Encyclopedia Iranica

- Browse UCB books in and about Judeo-Persian

- Study Persian and Hebrew in the UCB Department of Near Eastern Studies

Contribution by Alexander Warren Marcus

PhD Student, Department of Religious Studies, Stanford University

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Fath Nāma

Title in English: The Book of Conquests

Author: Emrānī, 1454-1536

Imprint: 1675-1724

Edition: Original manuscript

Language: Judeo-Persian

Language Family: Indo-European, Indo-Iranian

Source: The British Library

URL: http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Or_13704

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- The Bible as a Judeo-Persian Epic : an Illustrated Manuscript of ‘Imr̄anī’s Fatḥ-Nāma = Miḳra ke-epos Parsi-Yehudi : ketav yad meʼuyar shel ha-Fatḥ-Namah le-ʻImrani / Vera Basch Moreen with Orit Carmeli. Jerusalem : Ben Zvi Institute for the Study of Jewish Communities in the East, 2016.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

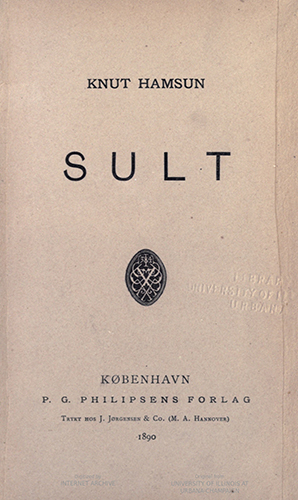

Norwegian

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

Det var i den Tid, jeg gik omkring og sulted i Kristiania, denne forunderlige By, som ingen forlader, før han har faaet Mærker af den . . .

It was in those days when I wandered about hungry in Kristiania, that strange city which no one leaves before it has set its mark upon him . . .

(trans. Sverre Lyngstad, 1996)

So opens Knut Hamsun’s novel, Sult (Hunger). When Sult was published in 1890, it represented a literary breakthrough not just in Scandinavia but also throughout Europe. Though Hamsun’s later novels would take more conventional forms, Sult was a harbinger of 20th century modernism for its stream-of-consciousness narration and its focalization of a vagabond figure who struggles to cope with modern urban life. The novel’s plot is spare: an unnamed—and unreliable—narrator arrives in Kristiania (now Oslo); he struggles to get work as a writer and has occasional run-ins with strangers; three months later, he leaves the city by boat. What makes the novel remarkable is how it portrays the inner life of a—literally—starving artist. Through the narrator’s increasingly wild musings, it is difficult for the reader to decipher whether the protagonist is insane or just hungry, and whether his hunger is forced upon him by poverty or voluntarily undertaken as part of a fascinating, yet ambiguous, creative project. As Hamsun put it elsewhere, Sult aims to reveal “the unconscious life of the soul.”[1]

Knut Hamsun is widely accepted as one of Norway’s greatest authors. He is second only to Henrik Ibsen in terms of international renown and he won the Nobel Prize for literature in 1920 for his novel Markens grøde (“Growth of the Soil”). However, his legacy has been hotly debated, and his reputation severely damaged, by his strong Nazi sympathies and support of the Nazi occupation of Norway (1940-45).

Though Sult was written in Norwegian, it is a Norwegian highly inflected by Danish spelling. For 400 years, Norway was under Danish rule, during which time Danish was the language of writing and instruction in Norway. After declaring independence from Denmark in 1814, Norwegians were eager to establish an official language that better reflected the range of Norwegian dialects, but this has proven to be a long and contentious process. When Sult was published, Norway still had a shared publishing culture with Denmark, and, indeed, the first edition of Sult was published in Copenhagen.

Hunger has been taught in various courses at UC Berkeley in the Department of Scandinavian, including undergraduate courses on “place in literature” and “consciousness in the modernist novel,” as well as in graduate courses on affect and fictionality. The department, which is one of only three independent Scandinavian departments in the United States, also offers courses in beginning and intermediate Norwegian, a language spoken by more than 5 million people. In addition to the 1890 first edition of Sult, the UC Berkeley Library owns multiple English translations of this landmark work.

Contribution by Ida Moen Johnson,

PhD Student in the Department of Scandinavian

Notes:

- This phrase comes from the title of Hamsun’s 1890 essay, “Fra det ubevidste Sjæleliv.”

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Sult

Title in English: Hunger

Author: Hamsun, Knut, 1859-1952

Imprint: Copenhagen: P.G. Philipsens Forlag, 1890.

Edition: 1st edition

Language: Norwegian

Language Family: Indo-European,

Source: The Internet Archive (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign)

URL: https://archive.org/details/sult00hams/page/n5/mode/2up

Other online editions:

- Hunger. Translated from the Norwegian of Knut Hamsun by George Egerton, with an introduction by Edwin Björkman. New York: A.A. Knopf, 1935, ©1920. HathiTrust

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Sult. København, P.G. Philipsen Forlag, 1890.

- Hunger. Translated into English by Sverre Lyngstad. New York: Penguin Books, 1998.

- Hunger. Introduction by Paul Auster; translated from the Norwegian and with an afterword by Robert Bly. New York: Noonday Press, 1998.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

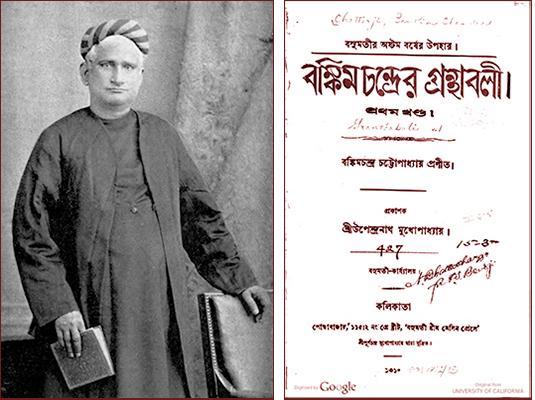

Bengali

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

Bankimacandra Cattopadhyaya (1838-1894) was not only the very first novelist of the Bengali language but is also considered one of its greatest. He wrote the first novel in Bengali as well as the first novel in English by an Indian. His works are still avidly read and a poem in his historical novel Anandamatha titled “Vande Matram” (“Hail Mother”) so inspired Indian freedom fighters it was officially adopted as India’s national song (not the same as the national anthem which is a poem by Tagore).

Bankim was born in a Brahim family, and grew up in the town of Midnapur where his father worked for the colonial government. After his education Bankim followed his father into civil service while at the same time pursuing a successful literary career. Starting with poetry he turned towards writing novels. His first published novel, Rajmohan’s Wife, was composed in English. However, he soon turned to Bengali and in 1865 published the very first novel in the language called, Durgesanandini (“Daughter of the Lord of the Fort”). He continued to write novels as well as satirical and humorous sketches. A commentary he wrote on the Gita was published posthumously.

Outside Bengal, his historical novel Anandamatha (“The Monastery of Bliss”), published in 1882, became the most famous and somewhat controversial for its attitude towards Muslims. It is set during the Fakir Rebellion of the late 18th century when Bengalis rose up against the oppressive rule of the East India Company during a famine. As mentioned above, it contains an ode to the motherland conceived as a goddess titled “Vande Matram” that became very popular with Indian freedom fighters during the struggle for independence. Bankim’s political stances got him in trouble with British authorities in his own lifetime, but in 1894—the same year he died—Queen Victoria made him a Companion of the Order of the Indian Empire.

Bankim belonged to a generation of Bengalis who had grown up under British rule and were able to reflect on the massive changes that rule had brought. The generation immediately before his had been the first to be exposed to western and modern ideas, and many of them accepted them with enthusiasm while others did so reluctantly. While Bankim did not question the adoption of western and modern ideas and technologies, he and members of his generation were more familiar with them and were in a position to critically judge the promises the British had made to Indians about the benefits of European rule and civilization. At the same time they had gained the confidence to appreciate aspects of their Indian and Hindu heritage which they wanted to hold onto as they modernized. Apart from their literary merits, these are some of the themes that make Bankim’s works relevant to this day.

Bengali, or Bangla to its nearly 230 million speakers, is an Indo-Aryan language belonging to the Indo-European family of languages. It is the official and predominant language of Bangladesh and the Indian state of West Bengal, and also has many speakers in the neighboring Indian states of Tripura and Assam. With a rich and centuries old literary tradition it continues to be a major language of modern South Asia. At UC Berkeley, introductory and intermediate Bengali is taught through the Department of South & Southeast Asian Studies.

Contribution by Adnan Malik

Curator and Cataloger for the South Asia Collection

South/Southeast Asia Library

Title: Granthabali

Title in English: Collected Works

Authors: Caṭṭopādhyāẏa, Baṅkimacandra, 1838-1894.

Imprint: Kalikata : Upendra Nath Mukhopadhyaya, Basu Mati Office, 1310-11 [1892/93-93/94].

Edition: 1st

Language: Bengali

Language Family: Indo-European, Indo-Aryan

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (UC Berkeley)

URL: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100787603

Other online editions:

- Bankim Rachanabali (volume 1 of complete works in Bengali), Internet Archive (Digital Library of India)

- The Abbey Of Bliss (English translation of Anandamath), Internet Archive (British Library)

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Granthabali. Kalikata : Upendra Nath Mukhopadhyaya, Basu Mati Office, 1310-11 [1892/93-93/94].

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

ucblib.link/languages

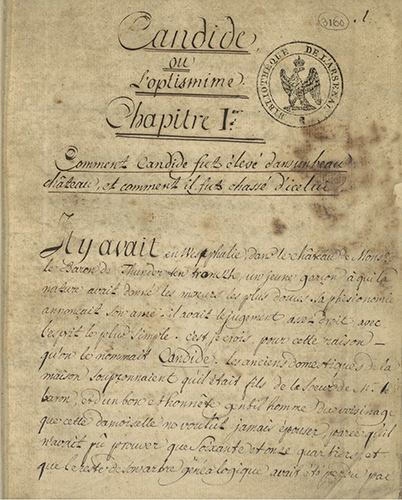

French

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

Si c’est ici le meilleur des mondes possibles, que sont donc les autres?

If this is the best of all possible worlds, what are the others like?

— Voltaire, Candide, ou, l’Optimisme (trans. Burton Raffel)

Voltaire, né François-Marie Arouet (1694-1778), was a French philosopher who mobilized the power of Enlightenment principles in 18th-century Europe more than any other thinker of his day. Born into a prosperous bourgeois Parisian family, his father steered him toward law, but he was intent on a literary career. His tragedy Oedipe, which premiered at the Comédie Française in 1718, brought him instant financial and social success. A libertine and a polemicist, he was also an outspoken advocate for religious tolerance, pluralism and freedom of speech, publishing more than 2,000 works in all possible genres during his lifetime. For his bluntness, he was locked up in the Bastille twice and exiled from Paris three times.[1] Fleeing royal censors, Voltaire fled to London in 1727 where he, despite arriving penniless, spent two and a half years hobnobbing with nobility as well as writers such as Alexander Pope and Jonathan Swift.[2]

After his sojourn in Great Britain, he returned to the Continent and lived in numerous cities (Champagne, Versaille, Amsterdam, Potsdam, Berlin, etc.) before settling outside of Geneva in 1755 shortly after Louis XV banned him from Paris. “It was in his old age, during the 1760s and 1770s,” writes historian Robert Darnton, “that he wielded his second and most powerful weapon, moral passion.”[3] Early in 1759, Voltaire completed and published the satirical novella Candide, ou l’Optimisme (“Candide, or Optimism”) featured in this entry. In 1762, he published Traité sur la tolerance (“Treatise on Tolerance”), which is considered one of the greatest defenses of religious freedom and human rights ever composed. Soon after its publication, the American and French Revolutions began dismantling the social world of aristocrats and kings that we now refer to as the Ancien Régime.[4]

With Candide in particular, Voltaire is credited with pioneering what is called the conte philosophique, or philosophical tale. Knowing it would scandalize, the story was published anonymously in Geneva, Paris and Amsterdam simultaneously and disguised as a French translation by a fictitious Mr. Le Docteur Ralph. The novella was immediately condemned for its blasphemy and subversion, yet within weeks sold 6,000 copies within Paris alone.[5] Royal censors were unable to keep up with the proliferation of illegal reprints, and it quickly became a bestseller throughout Europe.

Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (1726) is considered one of its clearest precursors in both form and parody. Candide is the name of the naive hero who is tutored by the optimistic philosophy of Pangloss, who claims that “all is for the best in this best of all possible worlds” only to be expulsed in the first few pages from the opulent chateau in which he grew up. The story unfolds as Candide travels the world and encounters unimaginable human suffering and catastrophes. Voltaire’s satirical critique takes aim at religion, authority, and the prevailing philosophy of the time, Leibnizian optimism.

While the classical language of Candide is more than 260 years old, it is easy enough to comprehend today. As the lingua franca across the Continent, French was accessible to a vast French-reading public since gathering strength as a literary language since the 16th century.[6] However, no language stays the same forever and French is no exception. Old French, which is studied by medievalists at Berkeley, covers the period up to 1300. Middle French spans the 14th and 14th centuries and part of the early Renaissance when the study of French language was taken more seriously. Modern French emerged from one of the two major dialects known as langue d’oïl in the middle of the 17th century when efforts to standardize the language were taking shape. It was then that the Académie Française was established in 1635.[7] One of its members, Claude Favre de Vaugelas, published in 1647 the influential volume, Remarques sur la langue françoise, a series of commentaries on points of pronunciation, orthography, vocabulary and syntax.[8]

At UC Berkeley, scholars have been analyzing Candide and other French texts in the original since the university’s founding. The Department of French may have the largest concentration of French speakers on campus, and French remains like German, Spanish, and English one of the principal languages of scholarship in many disciplines. Demand for French publications is great from departments and programs such as African Studies, Anthropology, Art History, Comparative Literature, History, Linguistics, Middle Eastern Studies, Music, Near Eastern Studies, Philosophy, and Political Science. The French collection is also vital to interdisciplinary Designated Emphasis PhD programs in Critical Theory, Film & Media Studies, Folklore, Gender & Women’s Studies, Medieval Studies, and Renaissance & Early Modern Studies.

UC Berkeley’s Bancroft Library is home to the most precious French holdings, including medieval manuscripts such as La chanson de geste de Garin le Loherain (13th c.) and dozens of incunables. More than 90 original first editions by Voltaire can be located in these special collections, including La Henriade (1728), Mémoires secrets pour servir à l’histoire de Perse (1745) Maupertuisiana (1753), L’enfant prodigue: comédie en vers dissillabes (1753) and a Dutch printing of Candide, ou, l’Optimisme (1759). Other noteworthy material from the 18th century overlapping with Voltaire include the Swiss Enlightenment and the French Revolutionary Pamphlet collections.

Contribution by Claude Potts

Librarian for Romance Language Collections, Doe Library

Sources consulted:

- Davidson, Ian. Voltaire. New York: Pegasus Books, 2010. xviii

- Ibid.

- Darnton, Robert. “To Deal With Trump, Look to Voltaire,” New York Times (Dec. 27, 2018).

- Voltaire. Candide or Optimism. Translated by Burton Raffel. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005.

- Davidson, 291.

- Levi, Anthony. Guide to French Literature. Chicago: St. James Press, c1992-c1994.

- Kors, Alan Charles, ed. Encyclopedia of the Enlightenment. Oxford University Press, 2002.

- Ibid.

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Candide, ou L’optimisme (Manuscrit La Vallière)

Title in English: Candide, ou L’optimisme (La Vallière Manuscript)

Author: Voltaire, 1694-1778

Imprint: La Vallière (Louis-César, duc de). Ancien possesseur, 1758.

Edition: 1st edition

Language: French

Language Family: Indo-European, Romance

Source: Gallica (Bibliothèque nationale de France, Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, 3160)

URL: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b520001724

Other online editions:

- Candide, ou l’Optimisme , traduit de l’allemand de M. le docteur Ralph. Paris: Lambert, 1759. (Gallica)

- Candide, ou l’Optimisme. Première Partie 1. Édition revue, corrigée et augmentée par l’auteur. Aux Delices, 1763.(Gallica)

- Candide, ou l’Optimisme, traduit de l’allemand de M. le docteur Ralph. Seconde partie. Aux Delices, 1761. (Gallica)

- Candide ou L’optimisme. Préface de Francisque Sarcey; illustrations de Adrien Moreau. Paris: G. Boudet, 1893. (Gallica)

- Candide, ou, L’optimisme. Illustré de trente-six compositions dessinées et gravées sur bois par Gérard Cochet. Paris: Les Editions G. Crès et Cie, 1921. (HathiTrust)

- Candide, or Optimism. Translated into English by Burton Raffel. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005. (ebrary-UCB access only)

- Candide / Voltaire. [United States]: Tantor Audio: Made available through hoopla, 2006. ebook and audiobook (OverDrive-UCB access only)

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Candide, ou, l’Optimisme / traduit de l’allemand de Mr. le docteur Ralph. Amsterdam: Marc-Michel Rey, MDCCLIX [1759].

- Candide, ou, L’optimisme. Édition présentée, établie et annotée par Frédéric Deloffre. Paris: Gallimard, 2003.

- Candide. [Graphic novel] Interventions graphiques de Joann Sfar. Rosny: Éditions Bréal, 2003.

- Candide, or Optimism. Translated and edited by Theo Cuffe with an introduction by Michael Wood. New York : Penguin Books, 2005.

- Candide, ou L’optimiste. [Graphic novel] Scénario, Gorian Delpâture & Michel Dufranne; dessin, Vujadin Radovanovic; couleur, Christophe Araldi & Xavier Basset. Paris: Delcourt, 2013.

- Candide or, Optimism: The Robert M. Adams Translation, Backgrounds, Criticism. Edited by Nicholas Cronk. New York : W. W. Norton & Company, 2016.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

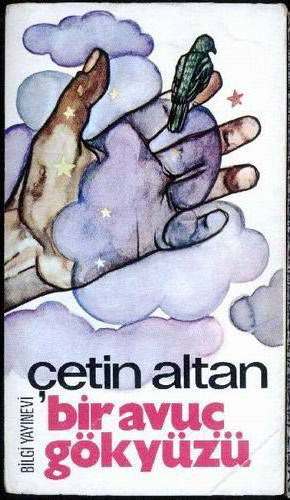

Turkish

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

The Turkish writer Çetin Altan (1927-2015) was a politician, author, journalist, columnist, playwright, and poet. From 1965 to 1969, he was deputy for the left-wing Workers Party of Turkey—the first socialist party in the country to gain representation in the national parliament. He was sentenced to prison several times on charges of spreading communist propaganda through his articles. He wrote numerous columns, plays, works of fiction (including science fiction), political studies, historical studies, essays, satire, travel books, memoirs, anthologies, and biographical stories.[1]

His novel Bir Avuç Gökyüzü (A Handful of Sky), was published in 1974 and takes place in Istanbul. A 41-year-old politically indicted married man spends two years in prison and then is released. Several months later he is called into the police station where the deputy commissioner has him sign a notification from the public prosecutor’s office. This time, the man will serve three more years and he has a week to surrender to the courthouse. The novel chronicles the week of this man’s life before he serves his extended sentence. Suddenly, an old classmate with thick-rimmed glasses appears with the pretense to help. The classmate convinces the main character to petition his sentence and have it postponed for four months so that he can make the necessary arrangements to support his family. Unsurprisingly, the petition is rejected on the grounds of the severity of the purported offense that led to conviction. His classmate then urges the protagonist to take a freighter and flee the country, but instead he turns himself in. From the prison ward’s iron-barred windows he can only see a handful of sky.[2] The protagonist experiences lovemaking with his mistress mainly as a metaphor for freedom lost; the awkward and clumsy sex he has with his wife, on the other hand, seems an apt metaphor for the emotionally inert life he leads both in and outside of prison.[3]

Çetin Altan was well aware of language’s power and wrote articles on the Turkish language in the newspapers where he was employed as a journalist. At the age of 82 and during his acceptance speech at the Presidential Culture and Arts Grand Awards in 2009, Mr. Altan said, “İnsan kendi dilinin lezzetini sevdiği kadar vatanını sever’’ (A person loves the homeland as much as he loves the flavor of his own language). He loved Turkish and wrote with that love. In his works, as he put it, he “never betrayed the language and the writing.”[4]

An argument can easily be made to study Turkish. There are 80 million people who speak Turkish as their first language, making it one of the world’s 15 most widely spoken first languages. Another 15 million people speak Turkish as a second language. For example there are over 116,000 Turkish speakers in the United States, and Turkish is the second most widely spoken language in Germany. Studying Turkish also lays a solid foundation for learning other modern Turkic languages, like Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Tatar, Uzbek, and Uighur. The different Turkic languages are closely related and some of them are even mutually intelligible. Many of these languages are spoken in regions of vital strategic importance, like the Caucasus, the Balkans, China, and the former Soviet Union. Mastery of Turkish grammar makes learning other Turkic languages exponentially easier.[5]

Turkish is not related to other major European or Middle Eastern languages but rather distantly related to Finnish and Hungarian. Turkish is an agglutinative language, which means suffixes can be added to a root-word so that a single word can convey what a complete sentence does in English. For example, the English sentence “We are not coming” is a single word in Turkish: “come” is the root word, and elements meaning “not,” “-ing,” “we,” and “are” are all suffixed to it: gelmiyoruz. The regularity and predictability in Turkish of how these suffixes are added make agglutination much easier to internalize.[5] [6] At UC Berkeley, modern Turkish language courses are offered through Department of Near Eastern Studies.[7]

When I was asked to write a short essay about the Turkish language based on a book, I was pleasantly surprised to discover that the UC Berkeley Library has many of Çetin Altan’s books in their original language. While he was my favorite author when I was in high school and in college in Turkey during the 1970s and 1980s, my move to the United States and life in general caused these memories to fade away. Now I am excited and feel privileged with the prospect of reading his books in Turkish again and rediscovering them after all these years.

Contribution by Neil Gali

Administrative Associate, Center for Middle Eastern Studies

Sources consulted:

- http://www.turkishculture.org/whoiswho/memorial/cetin-altan-953.htm (accessed 3/10/20)

- https://www.evvelcevap.com/bir-avuc-gokyuzu-kitap-ozeti (accessed 3/10/20)

- “İnsan kendi dilinin lezzetini sevdiği kadar vatanı sever,” (October 21, 2017) P24: Ağimsiz Gazetecilik Platformu = Platform for Independent Journalism. http://platform24.org/p24blog/yazi/2492/-insan-kendi-dilinin-lezzetini-sevdigi-kadar-vatani-sever (accessed 3/10/20)

- İrvin Cemil Schick, “Representation of Gender and Sexuality in Ottoman and Turkish Erotic Literature,” The Turkish Studies Association Journal, Vol. 28, No. 1/2 (2004), pp. 81-103, https://www.jstor.org/stable/43383697 (accessed 3/10/20)

- https://names.mongabay.com/languages/Turkish.html (accessed 3/10/20)

- https://www.bu.edu/wll/home/why-study-turkish (accessed 3/10/20)

- http://guide.berkeley.edu/courses/turkish (accessed 3/10/20)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Bir Avuç Gökyüzü

Title in English: A Handful of Heaven

Author: Altan, Çetin, 1927-2015

Imprint: Kavaklıdere, Ankara : Bilgi Yayınevi, 1974.

Edition: 1st edition

Language: Turkish

Language Family: Turkish, Turkic

Recommended Online Resource:

“İnsan kendi dilinin lezzetini sevdiği kadar vatanı sever,” (October 21, 2017) P24: Ağimsiz Gazetecilik Platformu = Platform for Independent Journalism. Blog post of tribute to the writer with photos, videos, etc.

http://platform24.org/p24blog/yazi/2492/-insan-kendi-dilinin-lezzetini-sevdigi-kadar-vatani-sever (accessed 3/10/20)

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Give Big to Languages at Berkeley

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

Support research, teaching, and learning of diverse non-English languages at UC Berkeley today. #CalBigGive

Support research, teaching, and learning of diverse non-English languages at UC Berkeley today. #CalBigGive

Art History/Classics Library Fund

University Library

East Asian Library Fund

University Library

South/Southeast Asian Library Fund

University Library

Library Collections Fund

University Library

Berkeley Language Center Fund

College of Letters & Science

Visit biggive.berkeley.edu for other library fundraising programs.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

http://ucblib.link/languages

Breton

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

“Lec’h ma vije ‘r zorserienn hag ar zorserezed;

Hag a diskas d’in ‘r secret ewit gwalla ann ed.”

“Where were the wizards and witches,

for they are are the ones who taught me how to spoil the wheat.”

from “Janedik ar zorseres” in Gwerziou Breiz-Izel: Chants populaires de la Basse-Bretagne

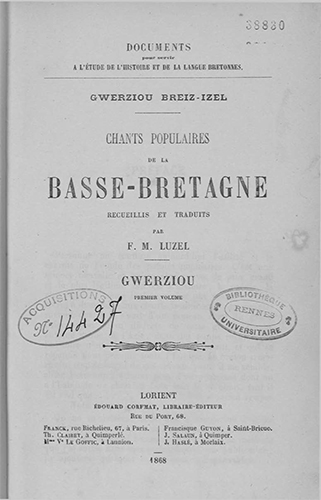

François-Marie Luzel (1821-1895) was a French folklorist and Breton-language poet who assumed a rigorous approach to documenting the Breton oral tradition. After publishing a book which included some of his own poetry in 1865 entitled Bepred Breizad (Always Breton), he published a selection of the texts that he collected in the two-volume set Chants et chansons populaires de la Basse-Bretagne (Melodies and Songs from Low-Brittany) in 1868. It is this latter work that is featured here and offers a parallel translation in French with the intent of making the corpus of songs available to as wide a readership as possible. Throughout the 19th century, Celtic revivalists such as the controversial Théodore Hersart de la Villemarqué undertook an equally ambitious project to collect, preserve, and disseminate folk songs and stories. According to Stephen May, “The modern Breton nationalist movement draws heavily on the persistence of Breton traditions, myths memories and symbols (including language) which have survived in various forms, throughout the period of French domination since 1532.”[1]

Of the many minority languages spoken in France today, Breton (Brezhoneg) is the only one of the Celtic branch of the Indo-European family. Its history can be traced to the Brythonic or Brittonic language community that once extended from Great Britain to Armorica (present-day Brittany) and as far as northwestern Spain beginning in the 9th century. It was the language of the upper classes until the 12th century, after which it became the language of commoners in Lower Brittany as the nobility adopted French. Because of the predilection for French and Latin in the early modern and modern periods, there exists a limited tradition of Breton literature. After the revolution of 1789 when French became the official language, regional languages and dialects became viewed as anti-democratic and hence prohibited in commercial and workplace communications. The Loi Deixonne of 1951 opened the doors grudgingly for the teaching of Breton in France together with Basque, Catalan and Occitan. There has since been some expansion to roughly 5% of the school population.[2] Despite a flowering of literary production since the 1940s, Breton has been classified as “severely endangered” with approximately 250,000 native speakers.[3] Since 1911, Breton has been a core language taught in UC Berkeley’s Celtic Studies program, the oldest of its kind in the country.[4]

Contribution by Claude Potts

Librarian for Romance Language Collections, Doe Library

Sources consulted:

- May, Stephen. Language and Minority Rights: Ethnicity, Nationalism and the Politics of Language. 2nd New York: Routledge, 2012.

- Price, Glanville. Encyclopedia of the Languages of Europe. Oxford, UK: Blackwell, 1998.

- UNESCO Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger, http://www.unesco.org/languages-atlas.

- History of Celtic Studies at UC Berkeley, http://celtic.berkeley.edu/celtic-studies-at-berkeley

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Gwerziou Breiz-Izel: Chants populaires de la Basse-Bretagne, recueillis et traduits par F.M. Luzel

Title in English: Gwerziou Breiz-Izel: Melodies and Songs from Low-Brittany

Author: Luzel, François-Marie, 1821-1895.

Imprint: Lorient, É. Corfmat; [etc., etc.] 1868-74.

Edition: 1st edition

Language: Breton

Language Family: Indo-European, Celtic

Source: Université de Rennes 2

URL: http://bibnum.univ-rennes2.fr/items/show/321

Other online editions:

- HathiTrust Digital Library: Luzel, François-Marie, 1821-1895. Gwerziou Breiz-Izel: Chants populaires de la Basse-Bretagne. vols. 1-2. Lorient: É. Corfmat; [etc., etc.], 1868-74.

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Luzel, François-Marie, 1821-1895. Gwerziou Breiz-Izel: Chants populaires de la Basse-Bretagne. vols. 1-2. Lorient: É. Corfmat; [etc., etc.], 1868-74.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

![The Languages of Berkeley [fan]](https://update.lib.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/fan_languages-450px.jpg)