Tag: UC Berkeley Oral History Center

David C. Driskell: Life Among the Pines

In April 2019, Dr. Bridget Cooks and I had the privilege of conducting a series of oral history interviews with artist and educator David C. Driskell for the Getty Research Institute’s African American Art History Initiative. David and his wife, Thelma, welcomed us into their home, where we spent hours speaking with David about his singular life and extraordinary contributions to art and African American art history. It was a surreal experience to sit behind the camera and look around at beautiful works of art while David skillfully engaged us with stories from his life and work. In recounting his past, David employed accents and well-timed jokes that had us in stitches. It was a pleasure to watch a gifted storyteller at work.

One year later, I learned from Bridget that this kind, funny, and smart man had passed away from complications due to the coronavirus on April 1, 2020. In a year filled with so much loss and change, David’s passing still hit hard. With David’s passing, the world lost not only a bright personality, but also a brilliant mind who championed the field of African American art history. And despite the uncertainty of these early days of the pandemic, I am happy to say that the Oral History Center was able to expedite the finalization of David’s oral history transcript, which is now available to the public.

Now another April has arrived. At the Oral History Center our work remains remote, but people across the country have been vaccinated against the coronavirus, and there is hope that the end of the pandemic is in sight. It is past time to take stock and reflect on those we have lost and the stories that remain with us. For me, David Driskell’s interview is one such story with staying power.

David C. Driskell was an artist and professor of art. He was born in Georgia in 1931, but mainly grew up in North Carolina. Driskell graduated from Howard University with a degree in painting and art history in 1955, attended the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in 1953, and earned an MFA from Catholic University in 1962, as well as a study certificate in art history from Rijksbureau voor Kunsthistorische Documentatie in 1964. Beginning in 1955, he taught at several colleges, including Talladega College; Howard University; Fisk University; and the University of Maryland, College Park. His influential artwork includes Young Pines Growing, Behold Thy Son, Of Thee I Weep, and Ghetto Wall #2. Driskell has curated important shows highlighting African American art history, including Two Centuries of Black American Art and Hidden Heritage: Afro-American Art, 1800-1950. He also helped establish The David C. Driskell Center for the Study of Visual Arts and Culture of African Americans and the African Diaspora at the University of Maryland, College Park, in 2001. Find this interview and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.

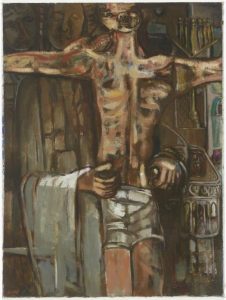

Throughout his many years making art, David experimented with different media and subjects, often with the recurring theme of pine trees. Yet one of his most memorable pieces is Behold Thy Son from 1956, which is now at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. David painted this pietà – a subject in Christian art depicting the Virgin Mary cradling the dead body of Jesus – in response to the 1955 murder of Emmett Till. For many observers, this image captured the zeitgeist of the early Civil Rights movement.

Listen as David speaks about making this important piece:

When Bridget asked how David felt about Behold Thy Son over sixty years after painting it, he replied, “I think it is dated and tied to a time and period, but the fight goes on. It’s also showing you that time hasn’t changed that much. [Eric Garner and] ‘I can’t breathe.’ ” Indeed, the subject of violence against Black bodies remains tragically evergreen.

And yet, in part because of this turmoil for African Americans at midcentury, David found renewed artistic inspiration in the serenity of nature – especially pine trees. Listen as he explains this shift in his work:

David was indeed a talented artist and important educator, as Bridget eulogized so well in her obituary on ArtForum last year. But our oral history interviews with him also highlighted the fact that he was a deeply religious man, one who connected his spirituality and creativity with his passion for gardening. During an interview session after church on Palm Sunday, David said of these links between nature and religion, “From dust and dirt thou came, and so dust to dirt thou goest. I’ve got to be part of that process.”

He further explained:

“So gardening is to me like painting, in a way. It’s a part of the process of this creative spirit that I feel so close to. Can’t wait to get [to the house in Maine] and I often go to the garden before I go to the studio…Gardening is a part of my life. It’s a part of that kind of spiritual regeneration that comes with the natural process. It isn’t for me so much the biblical reference.”

As a further measure of the man, when we were wrapping up our final interview session, we asked David for his concluding thoughts, and he said, “Well, maybe the final say is none of this I could be doing without family.” He went on to praise his wife, Thelma, in particular for supporting his art career when it was just a dream.

To learn more about David C. Driskell’s extraordinary life and work, read his oral history transcript and watch his interview in full here, here, and here. Find this interview and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.

“‘Rice All the Time?’: Chinese Americans in the Bay Area in the Early 20th Century”

Miranda Jiang is an Undergraduate Research Apprentice at the Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley. She is a UC Berkeley history major graduating in Spring 2022.

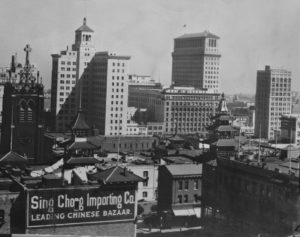

The Bay Area is home to San Francisco Chinatown, the first Chinatown in the United States. By the 1900s, there were second- and third-generation Chinese Americans living here who had spent their entire lives in the US. Interviews in the Oral History Center illuminate the experiences of these Chinese Americans who grew up in the Bay Area, and not just in Chinatown. What were the daily lives like of Chinese American youths living in Berkeley, or Emeryville, in the 1920s, 30s, and 40s? This is “Rice All the Time?”, an oral history performance about their experiences, brought to you in an audio format and performed by five young Chinese Americans.

This episode focuses on the experiences of one ethnic group. While we discuss Chinese American experiences with identity and discrimination, we recognize that this is just one part of a broad history of people of color in the United States. The murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, and countless other Black people, have made it even more evident that systemic bigotry is far from being a relic of history. We hope that after listening, you will engage in further conversation about racism in our nation and the complex experiences of people of color who live in the United States.

“Rice All the Time?” features direct quotes from interviews with Royce Ong, Alfred Soo, Maggie Gee, Theodore B. Lee, Dorothy Eng, Thomas W. Chinn, Young Oy Bo Lee, and Doris Shoong Lee. They describe their experiences with racial discrimination, through schoolyard bullying and housing exclusion. Some describe Chinese food with fondness, some with disdain. You will hear about after-school Chinese classes and the presence, or lack of, a local Chinese community.

This is a culmination of work I began in the fall of 2019 – I wrote a blog post about the process of creating the script.

While creating this performance, I related to some of their experiences, and was also surprised to hear many of them. It’s made me reflect on my conception of Chinese American history and my own identity as a Chinese American. I hope that “Rice All the Time?” fosters similar introspection in you.

Performed by Maggie Deng, Deborah Qu, Lauren Pong, and Diane Chao. Written and produced by Miranda Jiang. Editing and sound design by Shanna Farrell.

Cantonese readings of Young Oy Bo Lee’s lines accompany the English to reflect the original language of her interview.

Transcript:

Audio: (music)

Shanna Farrell: Hello and welcome to The Berkeley Remix, a podcast from the Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley. Founded in 1954, the Center records and preserves the history of California, the nation, and our interconnected world.

Lately, things have been challenging and uncertain. We’re enduring an order to shelter-in-place, trying to read the news, but not too much, and prioritize self-care. Like many of you, we’re in need of some relief.

So, we’d like to provide you with some. Episodes in this series, which we’re calling “Coronavirus Relief,” may sound different from those we’ve produced in the past, that tell narrative stories drawing from our collection of oral histories. But like many of you, we at the Oral History Center are in need of a break.

We’ll be adding some new episodes in this Coronavirus Relief series with stories from the field, things that have been on our mind, interviews that have been helping us get through, and find small moments of happiness.

Audio: (quotes spoken by performers, layered over each other)

(music)

Miranda Jiang: Hi, I’m Miranda Jiang, a history undergrad at UC Berkeley. You’re about to listen to an oral history performance I created called “‘Rice All the Time?’: Chinese Americans in the Bay Area in the Early 20th Century.” I originally intended for “‘Rice All the Time?” to be performed by a few of my fellow students in front of a live audience. But, of course, because of COVID-19 cancellations, we’re now bringing you this performance in an audio format.

“Rice All the Time?” presents perspectives of multiple Chinese people growing up in the Bay Area in the early 20th century. It places their words into conversation with each other, and it invites you, as listeners, to interpret them.

Before we get to the performance, I’d like to share with you a little background on the history of Chinese people in California.

Chinese immigration to the United States began in the mid-19th century. Thousands came to California as forty-niners during the Gold Rush. Racial resentment among white settlers in the West led to the passing of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which barred the immigration of Chinese laborers to the US. The Act slowed the entrance of Chinese men, and denied entrance to virtually all women except those married to merchants.

Chinese immigration continued despite the Exclusion Act, which was only repealed in 1943, along with other anti-Chinese regulations. The number of Chinese women in the US increased steadily after 1900. Chinese Americans in the Bay Area and elsewhere built vibrant communities.

This performance is made of direct quotes from oral histories in the archival collection of the Oral History Center of the Bancroft Library, here at UC Berkeley. It features the experiences of eight Chinese Americans who lived in the Bay Area from the 1920s to the 1950s. All, except one, were second or third-generation Chinese Americans who had spent all of their lives in the US. Alongside each other, these stories reveal a rich history and diversity of experiences within one ethnic group.

While you’re listening, I have some questions for you to keep in mind.

Think about what you know now of the Chinese American community in the Bay Area. Does hearing these experiences change your perception of their history? If so, how? What can their experiences with discrimination and identity teach us now, during the time of coronavirus and particularly visible racism against Asian people? How do you relate to these stories, many from almost a century ago?

After listening, I want to hear your feedback! Whether they’re answers to the questions I posed or other thoughts, please take a few minutes to fill out the Google form in the show notes. I appreciate any comments you may have, because your feedback will be super helpful to an article I’m working on about this project.

Now, please sit back and enjoy this performance of “Rice All the Time?”

Audio: (music)

Royce Ong (spoken by Diane Chao): There was not another Chinese family in Point Richmond, even a café or anything. Outside of my own relatives, I never had seen another Chinese.

Alfred Soo (spoken by Deborah Qu): … living in Berkeley, there weren’t very many Asians in my area. The Asians living in that area were probably my cousins.

Maggie Gee (spoken by Maggie Deng): It was before the onset of the war that brought in lots of people from elsewheres. Berkeley was integrated, in that sense… There were blacks, whites living in the neighborhood, quite a few Japanese, and some Chinese. More Japanese in my neighborhood than Chinese.

Theodore Lee (spoken by Lauren Pong): We didn’t know any Chinese. We lived in a neighborhood where we were the only Chinese. I went to a school where my family was the only Chinese in the school…

Dorothy Eng (spoken by Maggie Deng): [In Emeryville] there were three families, all Cantonese… It was an all white town. All [my mother] had was me, her children, and her husband whom she hardly knew.

Soo: … fortunately I didn’t experience any [teasing] that I can recall.

Eng: My father was very protective because he had seen the meanness to the Chinese, how they were treated, and he wanted to protect us because we were in a white community.

Theodore Lee: I wasn’t treated any differently because, remember now, these are people who are not snobby people; they’re working-class white, who tend, on the whole, to be friendly people. They’re not overly secure. There’s no snobbery. There’s no snobbery in our neighborhood. There was none.

Eng: … when I was in grammar school I hated it because I was never included, never included. All the years at grammar school I was not included in the classroom, I was not included in the playground. I can remember seeing myself going out during playtime, and I would be just standing there practically invisible. If I would go over to the rings because nobody else was there and start to swing, they would come and gather and push me off. The teachers were not there for you, the kids were just mean to you.

Audio: (sounds of children on a playground)

(music)

Ong: I think it was the Exclusion Act that didn’t allow the Asians to own property…“Asian” especially meant “Chinese…” The Exclusion Act had stopped them from immigrating and stopped them from owning property in the United States, especially California. I think they had their own law that was a little [more] stringent than the United States’ law. They were even segregated in the schools, when you read history.

Gee: I’ve lived around town in Berkeley, and Berkeley was a very difficult town to rent in, for non- whites … We really couldn’t find a place to live [there], because there would be a place available but when we came to see them, the place was rented. It became very discouraging… I sort of gave up. My sister, she’d call ahead of time and say that she was Chinese.

Thomas W. Chinn (spoken by Deborah Qu): We found out when we moved to San Francisco that the only place we could live in was Chinatown, because no one would rent to us or sell us a home outside of Chinatown.

Gee: I was hurt, more than anything else. Many years later I served on a commission on housing discrimination in the city of Berkeley. This was actually before the Rumford bill, and that was in the sixties. You’d think Berkeley, being a university city it’s an enlightened thing –– it’s just like any other city, though. People are frightened. If you allow a minority person to live [there], it would allow all the rest of the other minorities in. It’s really quite stupid… Yes, I was really disappointed in Berkeley.

Chinn: It was not a force of law; it was by word of mouth … no one wanted neighbors whose culture they did not understand or who could not speak to them in their own language.

Audio: (music)

Eng: When we moved to Oakland Chinatown I realized how different our family was from people I met in the church. Culturally, we were very different because we were brought up as a Christian family. We celebrated Christmas, Easter, 4th of July, all of the American holidays, also Thanksgiving. People in Chinatown did not celebrate these holidays. They celebrated the Chinese holidays, a big difference. When I joined the church, I realized this. They were all very curious about me because I was so different.

(Cantonese translation in the background, spoken by Lauren Pong): “旧金山的唐人街是 一个很好的社区。有好多山,好多缆车。又有中国餐馆、店铺、银行、医院…你需要的都有”

Young Oy Bo Lee (spoken by Miranda Jiang): San Francisco’s Chinatown was a nice community within a nice city. There were a lot of hills and cable cars. There were Chinese restaurants, shops, banks, hospitals and just about any kind of shop you would want. Also, Cantonese was the main dialect spoken so it felt comfortable. There were modern conveniences in all the houses. All of these things made the adjustment to the new country easier. Chinatown was a haven for the Chinese immigrant.

Audio: (sounds of Chinatown, erhu playing)

(Cantonese translation in the background, spoken by Lauren Pong) : 大部分人讲广东话,所以感觉好好。现代化的房屋,先进的设备,舒适的生活环境,新移民很容易过上新的生活

Doris Shoong Lee (spoken by Lauren Pong): At this time everyone in this area spoke Cantonese because most of the people in this area came from Guangdong. That is the one province in China that speaks Cantonese. So San Francisco Chinatown was all Cantonese speaking. It’s only been in the last maybe twenty, thirty years, since there has been a large influx of Chinese from other areas of China, that Mandarin is now spoken fairly commonly.

Chinn: My family hired some Chinese men to teach us how to write and speak Chinese, and how to read. But after spending all day in an American school, and then trying to revert back to a strange language that as children we never knew except for a few words from our parents, it was very hard. We were very poor Chinese scholars. That was one of the deciding factors for my parents––”Our children are getting too Americanized; they have no Chinese friends, they have no Chinese background. We think maybe we’d better move them back to San Francisco where they can live in Chinatown and learn more about their Chinese culture.”

Shoong Lee: I guess at that time there weren’t too many Chinese families that ventured and lived outside of Chinatown… San Francisco Chinatown has always been the very established community. But Oakland Chinatown at that time was rather small. Now it is quite different. It’s large.

Audio: (music)

Soo: I went to Chinese school in Oakland. So we’d take the streetcar to Oakland… In Chinatown. And we’d get there and start at 5:00 and start home at 8:00. That’s a long day.

Audio: (sound of streetcar and bell ring)

Shoong Lee: My dad wanted us to learn Chinese from the time we were in school. So we had tutors all the way through high school, my sister and I. The tutor came in five afternoons a week from four to six and Saturday mornings from ten to twelve…That’s a lot of Chinese…

Gee: When I was young, we used to have a teacher come to our house. It was really for my brother… to know Chinese. The girls got a little bit of Chinese…There used to be a name –– I forget what the word is, a very derogatory name for people who did not speak Chinese in the Chinese community. As I grew up, my mother was ashamed, a little bit. [laughs] Not really, though, but you know, people would always mention “Your children don’t speak Chinese.”

Ong: My mother knew English, but she always wanted to speak Cantonese, but I didn’t. I always answered in English, made her mad.

Gee: … with my generation, you didn’t want to speak Chinese, because you wanted to integrate. Didn’t want to eat with chopsticks, none of that. “Why are we having rice all the time?

Shoong Lee: I always loved my Chinese food… Sundays were always noodles at lunchtime. Those wonderful noodles. I can remember from the time I was maybe eleven, twelve, thirteen, on up, was that Sundays was when the New York Philharmonic came on the air. It was radio at that time, no television. Three o’clock in New York was lunch time in San Francisco. My sister and I would sit on the steps and have our lunch and listen to the New York Philharmonic.

Audio: (music, “Rhapsody in Blue”)

Ong: My mother cooked Chinese food and American food, but I don’t. I just eat regular American food.

Shoong Lee: We had Chinese meals for dinner but western breakfasts and lunch if we were home on the weekends. But dinner was always Chinese food. One of the things that Dad always wanted us to do was be able to name every dish that was on the table at night, and to speak Chinese at the dinner table.

Audio: (music, “Rhapsody in Blue”)

Chinn: We want to produce the concept of a Chinese-American who is striving hard to let people know that the Chinese part of a Chinese-American is something the Chinese are proud of, but at the same time they want to be known more as Americans.

Young Oy Bo Lee: I’m afraid the younger generation won’t understand this –– but holding on to traditions and customs is holding on to part of one’s identity. I hope that more of our young people will try to hold on to their Chinese identity and heritage.

(Cantonese translation in the background, spoken by Lauren Pong): 年轻一代不理解这 一点 —

保持传统同习俗,是坚持自己身份的一部分。我希望更多的年轻人会继续保持自己华人的身份同传统。

Chinn: I think if you are born a Chinese, sooner or later you come to appreciate the background and the culture of things Chinese. I know that among our friends, all our children that are growing up do not have that much interest in Chinese culture, but as they approach middle age and thereafter, then they pick up and want to learn more about their language and background.

Audio: (music)

Jiang: Thank you so much for listening to this oral history performance. I hope that it sparks your interest in the full interviews with each individual featured in the podcast. Many of these interviews include videos in addition to a printed transcript, and you can easily access them through the Oral History Center website and in the show notes.

Audio: (music)

Jiang: I’d like to thank our performers, Maggie Deng, Deborah Qu, Lauren Pong, and Diane Chao, for their wonderful work. I thank my mentors, Amanda Tewes and Roger Eardley-Pryor for making this episode come to fruition. Thanks so much to Shanna Farrell for being our editor and sound designer. And thank you to the people whose interviews were featured in this performance: Royce Ong, Alfred Soo, Maggie Gee, Theodore B. Lee, Dorothy Eng, Thomas W. Chinn, Young Oy Bo Lee, and Doris Shoong Lee.

Once again, don’t forget to send your reactions to this episode! I want to hear your thoughts, however long. There’s a link to a Google form in the show notes that includes a few questions about your listening experience.

Thank you for listening to “‘Rice All the Time?” I hope you enjoyed the performance and that you have a wonderful rest of your day.

Audio: (music)

Farrell: Thanks for listening to The Berkeley Remix. We’ll catch up with you next time. And in the meantime, from all of us here at the Oral History Center, we wish you our best.

The Library Is More Than a Place

by Katherine Y. Chen

When I first began at Cal, I was excited to experience dorm life, take interesting classes, and study with my friends in the library. Before working at the Oral History Center, I viewed the library as merely a physical space to sit and study. However, working at the Oral History Center (OHC) quickly dispelled this false notion.

Through my tenure at the OHC and my experience with research from my classes, I have learned that the library is more than a building in which to study. The library offers a multitude of resources for students — databases encompassing different topics and mediums such as ProQuest for newspaper articles, librarians ready to assist students in planning out papers, and primary sources such as personal interviews. After an informative meeting with a librarian introducing all these resources and more, I quickly began to utilize them in my research. I spoke to a librarian who helped me find multiple sources for my papers; I learned how to navigate the infinite databases accessible to students; and I learned which database to use to find specific types of sources.

Furthermore, my work at the OHC greatly helped me hone my research skills. I learned how to navigate an archive, how to find specific information, and had the opportunity to help fellow students as well. While promoting the Carmel and Howard Friesen Prize in Oral History Research to my peers, I was able to utilize all the skills I had learned. I helped students navigate the OHC’s archive to find interviews, and gave advice on further research.

I became very familiar with the different projects and subject areas the OHC has to offer. My personal favorites are the Women Political Leaders project and the Dreyer’s Grand Ice Cream project. It was gratifying and empowering to read about the impact women had on politics, especially as an Asian American woman who intends to pursue law. Furthermore, ice cream is a favorite treat of mine, and to learn about how Dreyer’s Grand Ice Cream became widely popular was incredibly interesting.

My experience at the OHC exposed me to the many resources the library has to offer. In turn, I aimed to introduce my peers to the wonders of the library. For example, my friend was writing a research paper for her class and was having trouble keeping her sources in one accessible place. Based on what I learned, I recommended the saving grace of my paper to her — Zotero. Zotero is a program used to store and cite sources, and a librarian recommended it to me after I described having the same issue. Once downloading Zotero, my friend had a much easier time with her sources, and citing them was even easier.

Additionally, I recommended an oral history to another friend of mine who needed to find a primary source for their paper. They needed a source from a specific era, and I remembered reading over oral histories that fit what they were looking for. I sent over the link for the AIDS Epidemic in San Francisco Oral History Project. I wanted to show my peers that the library is not just a building to study in, but a plethora of resources right underneath their noses.

To everyone reading, especially Cal students, take the time to learn more about the resources at the library. Take advantage of all the library has to offer, and I guarantee you will be all the better for it.

Katherine Y. Chen just finished her first year at Berkeley. She is majoring in rhetoric with a minor in public policy.

Chinese-American Identity and Oral History Performance: Rewriting the Script

Miranda Jiang is an Undergraduate Research Apprentice at the Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley. She is a UC Berkeley history major graduating in Spring 2022.

In the fall of 2019, I joined an undergraduate research apprenticeship on oral history performance with Oral History Center interviewers Amanda Tewes and Roger Eardley-Pryor. Though I’d had some previous experiences with oral history, I wasn’t entirely sure what oral history performance was. I had my speculations: I was familiar with The Laramie Project and some other full-length plays which drew from oral histories. But no matter what the form of the performance would be, I understood that the project would take an approach to history that prioritized and shared the voices of ordinary people.

During the first few weeks of the semester, we discussed readings that fleshed out my understanding of oral history, then introduced me to multiple forms of oral history performance. Through readings such as Lynn Abrams’s Oral History Theory and Natalie Fousekis’s “Experiencing History: A Journey from Oral History to Performance,” I learned that the process of creating an oral history involves both the interviewer and the narrator (the person being interviewed). An oral history is a conversation. Both participants contribute to the content and direction of an oral history, and thus how an experience gets told. Oral history performance presents these experiences to the public, and places the experiences of multiple narrators in conversation with each other.

With these readings and assignments in mind, I searched through the Oral History Center’s vast archive of interviews to find sources for my own oral history performance. The only criteria I initially had in mind were that the subject I chose should be a story I knew little about, that I felt was undertold, and was centered in the Bay Area. I read interviews from the Freedom to Marry Project and the Suffragists Oral History Project, ultimately deciding on the Rosie the Riveter Project. It included interviews from people of African American, Chinese, Japanese, indigenous, and other backgrounds, and it was centered around the Bay Area.

I eventually decided to focus this performance on Chinese-American experiences in the Bay Area. I hoped that by focusing on this one group, I could have more time to flesh out the details of their lives. I do not have my own living grandparents to speak to, so hearing these stories about what young Chinese-American people like me had experienced growing up in California in the 1920s to 1950s made me feel connected to people who lived nearly a century ago. Hearing them also made me realize just how varied our experiences were.

Over the next weeks, I compiled a large annotated bibliography of quotes from relevant interviews, highlighting themes which continuously reemerged. In the spring semester, Amanda, Roger, and I shared many conversations about what it means to create a cohesive script out of direct quotes from oral histories. When we chose which quotes to group together, which to place in conversation with each other, and how we ordered and extracted quotes, we were interpreting each quote’s meaning. We constantly thought about how to assemble a script that highlighted common themes in the experiences of Chinese Americans, without taking narrators’ words out of context or imposing our own interpretations onto the quotes and our audience.

I soon found that by placing quotes of similar subjects next to each other, meaningful similarities and contrasts revealed themselves on their own. For example, many of the interviewers asked if the narrators had experienced teasing as children. Alfred Soo, Dorothy Eng, and Theodore Lee all described growing up in neighborhoods where they were among the only Chinese people there. Soo, who grew up in Berkeley in the 1920s, did not recall any teasing from other children. Lee, who grew up in the 1930s in Stockton, described not being treated any differently, emphasizing the lack of “snobbery” among working-class white people. Eng, who grew up in Emeryville in the 1920s, described being persistently mistreated by kids and teachers throughout grammar school. As a Chinese American who encountered racial insensitivity in school in the early 2000s, I expected that stories of children who grew up in the “age of exclusion” (1882-1943) would easily reinforce my own experiences. And yet, these oral histories showed a more complicated reality than I anticipated.

Another primary goal of this performance is to point the general public towards reading the full transcripts of the interviews. In the final script, there is a quote from Royce Ong, who states that he “just [eats] regular American food.” When I first read this, I was amused and annoyed by how he discounted Chinese food as something strange, when it was his own culture. But reading more of the interview, I found that his comments revealed more about his unique creation of a Chinese-American identity. He discussed “Chinese American” and “Chinese” as very distinct identities, with different political interests. To Ong, he could be a proud Chinese American as someone who didn’t eat Chinese food and who also learned only English as a first language.

Working on this performance made clear that no universal set of criteria comes with identifying as Chinese American. It made me aware of the vast multitude of experiences of other Chinese Americans, which are different from my own and different from each other. The format of the script brought the diversity of Chinese and American life to the forefront, and allowed each narrator to speak about their experiences as they occurred. It was up to the audience to observe and consider the contradictions between quotes.

The final script I created acknowledges that different Chinese Americans had unique experiences, while also highlighting similar struggles and activities within the ethnic group. Many anecdotes are relatable to me, today, and to other Chinese Americans in 2020. And ultimately, while some narrators leaned more towards embracing American culture, and others more towards also preserving Chinese traditions, all of them expressed the same conflicts with identity as Chinese people living in California.

By mid-March, we had created a final draft of the script after many sessions of cutting, rearranging, and reading out loud. We initially planned to give the eight-minute performance at the April 29th Oral History Commencement in the Morrison Library, with four or five student performers of Chinese-American backgrounds. When the campus closed due to COVID-19, we switched to an online podcast format, with the same script and number of performers.

The podcast version will be available on The Berkeley Remix this summer. I’m excited to be able to share this performance with more people using the magic of the Internet. I hope you’ll stay tuned for more!

Kathleen Dardes and the Global Impact of the Getty Conservation Institute

The Getty Oral History Project includes interviews with individuals across the spectrum of the Getty Trust, including the Getty Conservation Institute (GCI), which does international work to advance the field of art conservation. Of the four programs in the Getty Trust, the GCI stands out both for its scientific collaboration with other Getty entities, and its dedication to sharing conservation information worldwide. Kathleen Dardes’ lengthy career working in various GCI training programs is emblematic of this mission.

Kathleen Dardes is the head of Collections at the Getty Conservation Institute. She studied art history and classics at Temple University in the 1970s, and then went on to study art conservation at the Courtauld Institute of Art in the 1980s, specializing in textile conservation. Dardes then worked as a conservator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine, and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. She joined the GCI in 1988 as the senior coordinator for the Training Program.

When Dardes joined the GCI in 1988, this Getty program was only three years old and trying to establish itself in the field. Dardes recalls working to build credibility as an international art conservation organization, and struggling against “skepticism” about this new Getty entity:

“I think part of it had to do with the fact that we were so darn rich, and we could buy pretty much anything we wanted and could do anything we wanted, and we weren’t beholden to anyone except our trustees. That gave us a certain freedom, which I think was sometimes resented in the broader field. So we had to prove ourselves.”

Part of the way the GCI proved itself was investing heavily in the international training programs Dardes helped create to share conservation best practices worldwide. These included the idea of preventive conservation, or delaying the deterioration of objects through procedures like managing collections environments. Dardes explained the need for this training, saying,

“In the field, you’d hear these funny stories about people making all sorts of elaborate measures to control environments in a gallery space or storage area, but the roof was leaking [laughs] or there was a pest issue or something. So we were looking at the small details, and not the larger system that the museum is.”

In recent years, the GCI has undertaken a project called MEPPI or Middle East Photograph Preservation Initiative. Dardes explained that the GCI and several partners worked hard to establish much-needed photograph preservation courses throughout the Middle East to help institutions protect these collections. This project included many challenges, not the least of which is political instability. In her interview Dardes shared the inspirational story of one MEPPI participant’s dedication to conservation, even in the midst of the Syrian Civil War:

“When we arranged a follow-up course in Lebanon, which was open to people from throughout the region, one of the participants in Syria, at great personal risk, got on a bus with her father, who was there to protect her, and took a bus from Syria to Beirut. Took her two days to do that, a trip that normally takes half a day. Couldn’t fly because it was too difficult to go to the airport, too risky, but came to Beirut to be with her old colleagues and take a course—which we all found absolutely stunning. But that’s how committed she was, not only to the course itself, to the collections she was in charge of, but also to the network that was forming. She wanted to see her old colleagues and be involved in this thing called MEPPI. So it sounds very pollyannaish, but it was a wonderful thing. People who don’t often have the opportunity to be involved in projects like this don’t take them for granted. It was something that we all thought was remarkable.”

Though she has not explicitly used her skills as a textile conservator while at the GCI, Dardes has found opportunities to engage with the larger implications of cultural heritage around the world. Indeed, being a part of the Getty Trust has opened global opportunities for her—and the GCI—to share and teach conservation best practices on an incredible scale.

To learn more about her work with the Getty Conservation Institute, check out Kathleen Dardes’ oral history!

From the Archives: Irvin Shiosee

By Miranda Jiang

Miranda Jiang is an Undergraduate Research Apprentice at the Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley. She is a UC Berkeley history major graduating in Spring 2022.

“I just can’t go out there with my Indian costume, because when I do that they might think, you know, oh, here comes a savage Indian.” — Irvin Shiosee

In 1942, Irvin Shiosee, a member of the Laguna Pueblo of the Southwest, moved with his family to Richmond’s boxcar village. Along with many members of the Acoma Pueblo, members of the Laguna Pueblo moved to this village (often referred to both as the Santa Fe Indian Village and the Richmond Indian Village) beginning in the 1920s. This migration followed a verbal agreement with the Santa Fe Railroad in California, which promised them employment in railroad maintenance and construction.

As part of the “Rosie the Riveter” project, the Oral History Center has conducted over 250 interviews with individuals who lived in the Bay Area during World War II, including people who lived in Richmond’s boxcar village. In his 2005 interview, Shiosee recalls his childhood there: he describes rows of around sixty boxcars placed along the railway, each housing one or more families. The children’s playground was a small “swamp” where they would take makeshift rafts and search for tadpoles. Among other anecdotes, Shiosee describes how his father built his family an oven to make sure they didn’t “lose any of [their] traditional food,” such as sweet “Indian pudding” made in the oven overnight.

Shiosee’s life within the village often seemed like a separate world from life outside and public school. Whereas day school at his old reservation was with other members of his tribe, at Peres Elementary School, there were Richmond-area children of many ethnicities. He had to learn English through Dick and Jane, and indigenous students were only allowed to speak English. He describes how students would “squeal on [them]” if they heard Shiosee or other Pueblo kids speaking Keresan. Subsequent punishments included standing against the wall or completing chores such as wood-chopping and cleaning the bathroom.

Shiosee also encountered stereotypical perceptions of indigenous people through his interactions with other children. On the first day of school, the teacher couldn’t pronounce his last name while introducing him to the class. He could see the surprise on his classmates’ faces upon hearing that he was an “American Indian boy.” The media only represented people like him in stories of “cowboys versus Indians,” so to these American children, indigenous people were the enemy.

“So that’s how they saw me,” he says, “as a savage Indian, I guess.”

Neither did the administration show much support. Children viewed him as a figure from fables and histories, and they would come up to pat him. When he whacked their hands away, teachers would send Shiosee to the principal’s office where he would be disciplined for fighting.

As Shiosee grew older, he became more and more aware of two separate realms. In his life outside the village, he knew he would face hostility if he showed his Pueblo identity. He describes walking to junior high school in the morning:

“I had to take off my Indian costume and hang it on this fence that I had to go through, and then put on my street clothes… ”

Yet despite going to school in an English-speaking environment and being pressured to assimilate, Shiosee remained closely connected with his culture and language. At the end of the interview, Shiosee describes his relationship with English and Keresan:

“English language to me is like I’m copying somebody. It’s not my natural language. The language that I speak comes from my heart on to you, you know. But to imitate somebody is not really from the heart. It’s coming from the mouth.”

In 1982, the Santa Fe Railroad shut off the power to the village. Although Richmond’s boxcar village was populated for around 60 years, it is now a relatively little known piece of Bay Area history. It has been documented in a number of writings, including essays by emeritus Oregon State University professor Kurt Peters (see “Boxcar Babies: The Santa Fe Railroad Village at Richmond, California, 1940-1945”). An event at Richmond’s Native Wellness Center in 2009 included three former inhabitants of the village as speakers, two of whom have interviews with the Oral History Center.

The boxcar village no longer exists physically, nor does it seem present in the Bay Area’s public consciousness. Although the inhabitants of the village attended local schools and events, and were spatially near other Bay Area neighborhoods, the Pueblo people preserved their culture and ways of life within the Richmond boxcar village. Ensuring knowledge of the Pueblo’s long history in the Bay Area is an important step towards recognizing what Shiosee already states in his interview: that rather than being faraway relics of history, he and his people are part of the present.

As a first step to learning more about the lives of Laguna and Acoma Pueblo people at this remarkable settlement, I encourage you to view the Rosie project’s compilation of interview segments related to the village. I further recommend reading and watching the full interviews, such as Irvin Shiosee’s interview.

Never Forget? UC Berkeley’s Oral History Center documents memories of the Holocaust for researchers and the public

“It’s too late now because there’s nobody I can ask.”

— Katalin Pecsi, child of Auschwitz survivor

The 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz is on January 27 of this year and 41% of Americans don’t know what Auschwitz is — including a whopping two-thirds of millennials. A recent survey found a stunning lack of basic knowledge in the United States about the Holocaust — defined by the US Holocaust museum as “the systematic, state-sponsored persecution and murder of six million Jews” that decimated the Jewish population in Europe. Almost one million Jews were killed in Auschwitz alone, the largest and most infamous of the death camps. With fewer and fewer Jews who experienced the Holocaust first-hand alive to tell their stories — the youngest survivors with memories of the camps are in their eighties and nineties today — the cry of Holocaust remembrance not to forget depends on a clear historical record.

Throughout the Oral History Center’s vast collection of interviews are more than 200 that reference the Holocaust. While there is no specific Oral History Center (OHC) project dedicated to documenting the Holocaust, interviews can be found within projects about food and wine, arts and letters, industry and labor, philanthropy, and more. Furthermore, our oral history collections about the history of UC Berkeley include memories of the Holocaust and its impact, including projects about the Free Speech Movement, the student political party SLATE, and faculty interviews. These oral histories document memories of the Holocaust from a multiplicity of perspectives, from the first-hand experiences of Jewish refugees who fled from Europe before it was too late, to Americans who first heard about the atrocities after the liberation of the camps. The Jewish narrators in particular talk about how the Holocaust was the driving factor in their careers, philanthropy, Israel advocacy, and political activism. These oral histories may be particularly interesting to scholars as they provide a different lens for looking at the Holocaust, capturing the histories of those who were being interviewed for other reasons, but nonetheless spoke about the impact of the Holocaust on their lives.

There are oral histories in the collection that preserve the experiences of Jewish refugees who managed to flee Europe before it was too late and build new lives for themselves in the United States. Alfred Fromm fled Germany for the US in 1936 and went on to build a successful wine distribution business; he became a philanthropist supporting numerous educational, cultural, and Jewish organizations, including UC Berkeley’s Magnes Museum. In 1939, violinist Sandor Salgo had a sponsor in the United States but was denied a visa from the US consul in Hungary, who said the Hungarian quota was filled until 1984. In tears, Salgo told a patroness that he would probably die in a concentration camp and she was able to intervene on his behalf; his brother died in Auschwitz. Berkeley Mechanical Engineering professor and dean George Leitmann escaped Nazi-occupied Austria in 1940 at the age of 15, a few years later to return to Europe during WWII as a US Army combat engineer. He was in the second wave of soldiers who liberated Landsberg Concentration Camp, and later served as a translator during the Nuremberg War Crime Trials. All these experiences influenced his scientific area of study in control theory — measuring risk, probability, and how to avoid catastrophe.

“We certainly got there in time to see the smoldering bodies they were trying to burn and the skeletons. That probably hit me more than it hit the rest of the guys, because here my father was still missing. I still had hopes to see him among the DPs [displaced persons].” — George Leitmann on the liberation of Landsberg concentration camp. His father did not survive.

The one collection of interviews that addresses the Holocaust in the most detail is that of the the San Francisco Jewish Community Federation Leadership. Here can be found the oral history of William Lowenberg, a Holocaust survivor, number 145382 of the Auschwitz-Birkenau killing complex. His interview details how as a teenager luck, good health, and his own survival strategies enabled him to survive his harrowing journey through extermination camps, the Warsaw Ghetto aftermath, and a death march, until he was liberated from Dachau concentration camp at the age of 18. After an attempt to go home (like so many, his house had been taken over), Lowenberg eventually settled in San Francisco, where the Jewish Family Services Agency helped him secure a job collecting rent for a realty company. He went on to become a major figure in industrial real estate in the city. Lowenberg gave back to the agency later, serving on the same committee that helped him, in the 1970s finding jobs for Jewish refugees from the Soviet Union. Of his life dedicated to philanthropic and political activism on behalf of the Jewish community and Israel, Lowenberg reflected, “I feel that Jewish survival depends on the Jews.”

“I was young, healthy, and I kept clean. I kept as clean as I could all of the time.” — William Lowenberg on his survival strategies

The OHC collection also includes interviews of those who were present for the liberation, like Berkeley History Professor Emeritus Richard Herr, who was serving in the Signal Intelligence Corps and visited Buchenwald shortly after the liberation. He describes the displaced persons wandering the streets, survivors in their striped pajamas, the pile of dead bodies. “I was told they’d died after the liberation. They’d just been in such poor shape. They were just skin and bones. It was terrible.”

The collection also includes interviews of those who didn’t directly experience the Holocaust, but heard about it through family, friends, teachers, even work acquaintances. Oral histories are unique in that they can include off-hand comments and asides that illuminate an era. Six million — two thirds of Europe’s Jews perished — but three million survived and many dispersed to other countries including the United States. Narrators would encounter these survivors, the tales of depravity would sear in their memories, and the narrators would sometimes make offhand remarks. Other narrators provide more details about the many facets of the Holocaust — resistance and the underground, escapes, refugees and displaced persons, concentration camps, the murder of entire families — such as the oral histories of Laurette Goldberg, who taught music at UC Berkeley; Berkeley MBA Ronald Kaufman; wine writer Mike Weiss; winery manager Morris Katz; economist Lester Telser; poet Carl Rakosi, and Berkeley student activist Daniel Goldstine.

Among these are the oral histories of children of Holocaust survivors, including Berkeley History Professor Emerita Paula Fass, Paula Kornell, and Katalin Pecsi. All of them attributed their careers to their parents’ experiences. Growing up in Hungary, Katalin Pecsi knew her father had survived Auschwitz, her uncle Buchenwald, and her paternal grandmother Dachau; but had been told they were political prisoners because of their affiliation with the Communist Party. She later learned that she was Jewish, that her mother’s entire family had been killed in the Holocaust, and began to question what she had been told. “When I was a child I was told that they were political prisoners because they never told me that we were Jewish… but I’m not sure that’s true that they arrived as political prisoners. I don’t know, it’s too late now because there’s nobody I can ask.” Learning about her Jewish heritage combined with her longing to know about her own family propelled Pecsi into a career in Holocaust remembrance, becoming the director of education at the Budapest Holocaust Memorial Center.

“My parents were both survivors of the concentration camps. They had lost families. Not just their parents and siblings, but in fact, husbands, wives and children. They were married to other people, and my mother had a son who was taken from her when he was three. My father had four children who were all taken away and died in Auschwitz. One of the things that’s very, very clear is that I became a historian because of it. I became a historian because history was always around.” — Berkeley Professor Paula Fass

“What the concentration camp [Dachau] instilled in my father was just the beauty of life, and I think he helped to instill…was the beauty of a vineyard or of a vine growing, or beauty of your garden or the beauty of winemaking.” — Paula Kornell, winemaker

The OHC collection includes numerous oral histories that touch on narrators’ reactions to learning about the Holocaust. Interviewers for the Rosie the Riveter World War II Homefront Collection, for example, frequently asked narrators, who came from many walks of life, when did they first learn about the Holocaust and what was their reaction. Like Beatrice Rudney and Bud Figueroa, narrators interviewed for the Rosie the Riveter collection generally responded that they learned about the horrors of the genocide after the war, sometimes mentioning newsreels (films of piles of naked corpses, survivors of skin and bones). Other narrators, sitting for longer life-history interviews, addressed this issue when talking about their childhoods. Oral histories of Jewish narrators reveal more knowledge about what was happening during the war itself, particularly those whose families housed refugees, or who received letters from family with news of mass killings — 13 family members gone — or whose letters from family in Europe just stopped one day, such as former Dean of Berkeley Law School Jesse Choper, Professor Emeritus of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Howard Schachman, Laurette Goldberg, Lester Telser, as well as Quaker activist Gerda Isenberg. Schachman observed, “I was certainly aware of what was going on to the Jews in Europe…. I doubted those people who claimed they weren’t aware of the Holocaust — it wasn’t called the Holocaust then.”

“I understood it during the war. There were always leaks of information of what was happening. Some people would escape from the concentration camps and come back and tell it.” — Jesse Choper, Dean Emeritus of Berkeley Law

The oral histories provide researchers with information about the range of feelings people had when they learned about the atrocities in the camps. Many of these are short responses to a direct question, such as in the Rosie the Riveter collection. Daniel Levin recalled a “sickening feeling;” DeMaurice Moses described being “inured to savagery by that time;” and as David Dibble remembered it, “You have to sort of genuflect and say, true, it was the worst thing that ever happened. And it was.” Some narrators recalled how other people talked about the Holocaust, and these interactions were indelible moments for them. Berkeley alumna and student activist Susan Griffin recalled an incident about four years after the war where her fellow Girl Scout Brownie troop members were laughing, saying Heil Hitler, and making the Nazi salute. She recalled the driver pulled over, emotional, and scolded that they must never do so again; and her grandparents, whom she described as “passive anti-Semites,” explained to the six-year-old “what an evil man Hitler was.” Berkeley History Professor Emeritus Larry Levine recalled being “shocked” when he was an undergraduate five years after the war ended, and an English professor told the class, “Don’t let the Jews tell you they are the only ones who have suffered.”

Some of the oral histories provide a glimpse into how the Holocaust affected Jewish Americans in the Baby Boom generation, living in its shadow. Berkeley alumna and student activist Julianne Morris, Adrienne Asch, and Wayne Feinstein recall how the Holocaust was something they always knew about, part of the culture. As Feinstein put it, “The first twenty or thirty years after the Second World War I think the Jewish community was in shock. And I grew up in that environment.” He described the Holocaust as “the primary motivation” for his lifelong dedication to Jewish education, cultural programs, and support for Israel.

“You couldn’t be a Jew in post-Holocaust America without knowing about the Holocaust. I mean, you grew up, you knew about the Holocaust, you knew about Israel.” — Adrienne Asch, disability rights activist and professor of bioethics

Finally, at least a few oral histories describe how narrators reacted upon visiting death camps as tourists years, even decades, after the end of the war. Through visiting these camps in person, these narrators came face to face with the scope of the horrors. Berkeley Economics Professor Emeritus and past director of the Institute of Industrial Relations, Lloyd Ulman, along with Marty Morgenstern, past director of Berkeley’s Center for Labor Research and Education, were taken to Auschwitz on a work trip to Poland. Ulman recalls how Morgenstern went outside and “put his head between his legs. He thought he was going to throw up or faint.” Ulman recalls “terrible things like seeing a whole collection of false teeth” [taken from the dead for their gold fillings] and feeling the “horror” that General Eisenhower had felt upon seeing the camps. Annette Dobbs also lived through the war but the enormity of the Holocaust really hit her when she visited Mauthausen Concentration Camp outside of Vienna in 1971. Expressing the sentiment of many of the narrators who spoke about the Holocaust, she said, “That day I made my own personal commitment to spend the rest of my life to see that nothing like that would ever happen to my people again.”

January 27, the date of the liberation of Auschwitz, is International Holocaust Remembrance Day.

Find these and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.

Women of SLATE: Susan Griffin and Julianne Morris

The Oral History Center has been conducting a series of interviews about SLATE, a student political party at UC Berkeley from 1958 to 1966 – which means SLATE pre-dates even the Free Speech Movement. The newest additions to this project include two women who joined SLATE in the early 1960s at a tumultuous time at UC Berkeley: Susan Griffin and Julianne Morris.

Susan Griffin is an accomplished writer, and was a member of the UC Berkeley student political organization SLATE in the early 1960s. Griffin grew up in Los Angeles, California. She attended UC Berkeley, where she became active in SLATE, attending protests and engaging in political discussions. Griffin left Berkeley in 1963, but continued to work as a writer in the San Francisco Bay Area, producing many works, including Woman and Nature: The Roaring Inside Her. Over the years, Griffin remained active in causes of social justice, including the women’s movement and anti war protests.

Julianne Morris is a former social worker and mediator, and was a member of the UC Berkeley student political organization SLATE in the early 1960s. Morris grew up in Compton, California, and attended UC Los Angeles, where she helped found the student political group PLATFORM based on discussions with SLATE members. She then transferred to UC Berkeley, where she became active in SLATE, attending protests and running for ASUC student representative. Morris stayed at UC Berkeley to earn her master’s in social work. She then moved to New York City in 1964 and was a social worker for many years, where she helped start women’s centers, rape crisis programs, and became a part of the women’s movement. She returned to Berkeley in the early nineties and reconnected with former SLATE friends through reunions and an ongoing political discussion group.

Griffin and Morris were among the second generation of SLATE activists and joined the group around the same time in 1960 – after the famous HUAC protest in May of 1960 and before the Free Speech Movement in 1964. They also have similar upbringings in Jewish (adoptive family, in Griffin’s case) and politically left families who feared encroaching McCarthyism. These backgrounds helped ignite a political consciousness in both women that led them to SLATE.

Griffin and Morris’s oral histories build on an archive of SLATE history, but they also speak specifically to their experiences as women in this group. Both recount instances of feeling marginalized as women, of being left to do the “scut work” like mimeographing and cooking for hungry activists. They even recount tensions at a 1984 SLATE reunion in which those newly empowered by feminism expressed displeasure with the way they had been treated; many of the men denied this discrimination, but others took it to heart and sincerely apologized. And yet, Griffin and Morris both were encouraged to run for ASUC office in the early 1960s, campaigning on the SLATE platform and often pushing their own boundaries of what they thought was possible. Despite the challenges of being a woman in this campus political group, there were still opportunities to grow as individuals and as leaders.

Listen as Susan Griffin and Julianne Morris share their memories of running for ASUC on the SLATE ticket at UC Berkeley:

Even though both Griffin and Morris had decreased participation in SLATE or left campus by 1964, their experiences in the organization clearly shaped their perspectives about politics and activism, particularly as they both became involved with the women’s movement. Griffin explained, “The guys may not have known it, but they were training feminist activists in all that period.”

Most importantly, by recalling their times with SLATE and later political work, both Griffin and Morris emphasized the importance of building and sustaining community in activist groups. For Morris, joining SLATE helped her find a place where she belonged. Griffin pointed to organizations of politically like-minded individuals as ways to create belonging and “joy” through an almost spiritual experience of protest.

Listen as Julianne Morris reflects on SLATE’s impact on the Free Speech Movement:

Come learn more about SLATE, and explore the oral histories of Susan Griffin and Julianne Morris!

New Release: Rick Laubscher – San Francisco Journalist, PR Executive, and Founder of Market Street Railway

Tod ay we are excited to release the oral history interview of Rick Laubscher. Born in 1949, Rick came of age amid the bustle of Market Street at the family’s business, Laubschers’ Delicatessen. It was in these early years that he developed a fascination in transportation, and a special love of streetcars; the “iron monsters” that rumbled through the streets of San Francisco and past the family’s delicatessen. He spent countless hours as a child drawing city maps (to scale) for his collection of Matchbox trams and buses. And during the age of lava lamps and flower power, his dorm room walls at U.C. Santa Cruz were adorned with transportation maps. Indeed, Rick had what he called “the transportation bug,” a condition that would only grow in time.

ay we are excited to release the oral history interview of Rick Laubscher. Born in 1949, Rick came of age amid the bustle of Market Street at the family’s business, Laubschers’ Delicatessen. It was in these early years that he developed a fascination in transportation, and a special love of streetcars; the “iron monsters” that rumbled through the streets of San Francisco and past the family’s delicatessen. He spent countless hours as a child drawing city maps (to scale) for his collection of Matchbox trams and buses. And during the age of lava lamps and flower power, his dorm room walls at U.C. Santa Cruz were adorned with transportation maps. Indeed, Rick had what he called “the transportation bug,” a condition that would only grow in time.

On the campus of U.C. Santa Cruz, however, Rick also developed an interest in journalism. He created the University’s first radio station, albeit unregistered with the FCC, and upon graduation headed to New York to study at the Columbia School of Journalism, where he was awarded the Pulitzer Fellowship. Returning to California, he started his career as a broadcast journalist with KGTV in San Diego. Here he helped pioneer live reporting in the Southern California market, and won two “Golden Mike” awards for his work. In 1977, Rick returned home to San Francisco as a reporter for KRON-TV. If Herb Caen was the voice of San Francisco, Rick Laubscher was certainly seen by some as the dandy of the city’s television news. Immaculately dressed in a three-piece suit, Rick reported on a number of historic events, most notably the assassination of Mayor George Moscone and Supervisor Harvey Milk. Rick knew both the victims and the killer, and his coverage of the tragedy won him an Emmy Award.

In 1980, Rick left broadcast journalism to embark on a new career as a public-relations executive with the Bechtel Group in San Francisco. Over the next two decades, he worked around the world on behalf of Bechtel, crafting communication programs for both the company and their international clients. In the process, he helped mend relations between San Francisco and its business community, fostering a network of associates that would open the door for a dual career in civic service.

Rick’s affinity for streetcars is matched only by his love for San Francisco. And for nearly forty years, while working for Bechtel and later in private practice, he undertook numerous projects to give back to the City by the Bay. He served on the executive boards of the Chamber of Commerce, SPUR, and the JASON Foundation for Education, and was the founding Chairman of the City Club of San Francisco, one of the first fully open business and civic organizations in the City’s financial district. Above all, he revamped Market Street Railway, the nonprofit that brought vintage streetcars back to San Francisco. What started with an idea among likeminded enthusiasts—Rick calls it a “Mickey Rooney / Julie Garland Moment” of “Why don’t we get the kids together and put on a show”—finally took root in the summer of 1983 with San Francisco’s Historic Trolley Festival. Its popularity and international acclaim quickly made the festival an annual event. And by 1995, streetcars once again became permanent fixtures on the City streets. As President and CEO of Market Street Railway, Rick guided this effort with unrelenting energy. He assembled a diverse cast of supporters, searched around the world to secure additional streetcars, and skillfully navigated the city bureaucracy to make his vision of permanent streetcar lines to San Francisco a reality. For the fourth-generation San Franciscan who excitedly watched the “iron monsters” rumble down Market Street as a kid, it was simply a labor of love.

This oral history offers a look at San Francisco through the eyes of one of its remarkable residents. From journalism to business and an astonishing array of civic endeavors, Rick Laubscher helped shape the city he called home.