Tag: oral history

Enlisting Humanity by Uplifting the Voices Who Have Gone Unheard: Undergraduate Research in Oral History

Enlisting Humanity by Uplifting the Voices Who Have Gone Unheard

By Emily Nodal

Emily Nodal, UC Berkeley Class of 2022, is a Society and Environment major in the Rausser College of Natural Resources with an emphasis on justice and sustainability while minoring in public policy. In Spring 2021, Emily worked with historian Roger Eardley-Pryor in the Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library and earned academic credits as part of Berkeley’s Undergraduate Research Apprentice Program (URAP). URAP provides opportunities for undergraduates to work closely with Berkeley scholars on research projects for which Berkeley is world-renowned. For her URAP project, Emily used oral history materials to create the video embedded below on “Environmental Justice, Systemic Racism, and Democracy.” She also suggested high school curriculum materials to accompany the video. Below, Emily shares the personal nature of her research.

For my URAP project during the Spring 2021 semester, I had the privilege of developing a high school curriculum on environmental justice utilizing the narratives and perspectives of those interviewed by the Oral History Center. This project was very personal to me because environmental injustice has become increasingly prevalent in my own community.

I grew up in the Inland Empire, an industrialized region in Southern California inhabited predominantly by low-income communities of color, where consistently poor air quality and smoggy days felt like the norm to my peers and me. In recent years, the rapid development of Amazon warehouses and corresponding traffic congestion has exacerbated the environmental vulnerability of my community’s exposure to environmental toxins and their subsequent health hazards.

Efforts in 2020 to expedite delivery services for the online shipping boom wrought by the coronavirus pandemic resulted in dramatic expansion of Amazon’s shipping facilities while further enriching the multi-billion dollar corporation. Amazon’s development efforts have heightened shipping efficiencies and brought new jobs to these predominantly low-income communities of color, while also disproportionately burdening the already polluted region with negative amenities and toxic hazards. According to the Inland Empire-based “People’s Collective for Environmental Justice,” the more than 3,000 warehouses in the Inland Empire are all sited in the highest percentile for toxic emissions in the state and the populations living within a half-mile radius of the warehouses are 85% people of color. As someone who grappled with the realities of environmental inequity directly, I welcomed the chance to expand my environmental justice research into an effective, oral history-based high school curriculum.

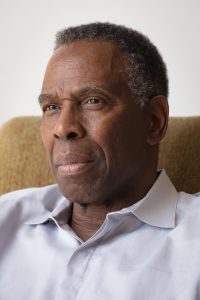

While exploring the array of interviews in the Sierra Club Oral History Project archive, I felt drawn to the narrative of Aaron Mair, a leader in the environmental justice movement and a former president of the Sierra Club. As a prominent Sierra Club leader from the EJ (environmental justice) movement and the first black president of the historically white environmental organization, Mair vividly illustrated how we, as environmental activists, must understand our environmental well-being as linked inextricably to the social, racial, and economic well-being of all others. Mair’s oral history became the basis for the educational video I created.

The ability of Mair and his family to endure the burdens of generational racism while at the same time upholding a connection to the natural world resonated with me and my own family’s experiences. Unlike the predominantly white leaders in the Sierra Club, many of whom began their activism focused on land and wildlife preservation, Mair’s lived experiences enabled him to see the cruciality of equitably uplifting all human and non-human stakeholders in conversations around environmental protection. He explained how his journey into the mainstream environmental movement came from his “family’s sense of home-place and a civil rights struggle, a migration struggle and pressure, dealing with the pressures of racism, while at the same time maintaining human dignity, but also maintaining a connection with their love of the natural beauty and wonders.”

Although I grew up in a low-income household, my family also valued the outdoors and took me camping in nature, which created my deep connection to and reverence for the natural world. However, I found my own experiences vastly different from many of my school peers from similar backgrounds. Environmental scholars like Carolyn Finney and Lauret Savoy have explored why many black and brown kids, from a young age, come to believe that nature and environmentalism isn’t for us. For too many of us, natural places and spaces are financially and even culturally inaccessible.

My engagement with Mair’s oral history narrative, coupled with my own experiences, reinforced how that racial exclusion emerged out of environmentalism’s flawed beginnings. Like many other movements in United States history, campaigns and institutions for wilderness preservation, land conservation, and modern environmentalism have been historically white-dominated. Mair examined this harmful past by reflecting upon his own organization and its founders, including the notoriously racist early UC Berkeley professor Joseph LeConte. As Mair explained in his oral history, LeConte “believed that African-Americans and Native Americans were inferior and separate and distinct races. He believed in his theory of life, which is that whites had a natural order and a higher chain of evolution over all things. He preached a theory of dominion over all things as opposed to stewardship of all things.” The problematic ideologies of early environmental advocates like Joseph LeConte permeated into the early environmental movement’s limited range of diversity and exclusionary land management practices. As described by Mair “it was them imposing upon [the land] their white will.”

In his oral history, Mair also explained how the environmental movement’s history continues to plague 21st century environmentalism in fundamental ways. Mair noted how “othering” marginalized groups historically has created contemporary environmental crises, as exclusion from environmental spaces has prevented those groups from becoming valid stakeholders in land-use decision making. Throughout most of its history, American environmentalism detrimentally established a dichotomy between humanity and nature, therefore requiring all humans not seen as “proper” stewards to be excluded. Mair critiqued this shortcoming in traditional environmental organizations, including in the Sierra Club, as advocating for the exclusion of humanity from nature in order to “save” it.

As Mair explained: “In the ‘saves,’ we create environmental organizations, and we become part of these clubs. And we think that the best way to protect land and nature is at the exclusion of humanity rather than the inclusion of humanity. It’s like building a fine Swiss watch and leaving out a master gear. And so, the ‘save’ organizations and their notion of preservation is missing a critical element, which is humanity, and humanity as a steward within that relationship. We should not be outside of it. Integral to the protection is our harmony with it… To me, that is like the story of the Yosemite Valley, how the First Nations were cleared out of the Yosemite Valley to protect it, even though they lived there for thousands of years… When humanity is relegated to being viewed as dirty or polluted in the eyes of the environment by other men, we lose something. That is indeed a crisis.”

The curriculum I created for this URAP project focused on environmental justice because if people of color remain socially, culturally, and economically disabled from accessing environmental spaces, then we will never be able to meaningfully contribute our widely diverse perspectives, experiences, knowledge, and solutions to the world’s escalating crises of climate change. Again, Aaron Mair articulated the need to expand and democratize marginalized communities’ access to environmental activism by his re-framing of the Sierra Club’s core mission to “enlist humanity.” Mair explained how “fundamentally in the United States as you enlist humanity in the United States, it’s through our democracy. It’s empowering our democracy. It’s empowering our humanity… And this is a huge linking of environmental rights, civil rights, voting rights, linking the fact that environmental [justice] is a function of a healthy democracy in civil society. The … fusion of the civil rights, environmental rights, and labor rights efforts really jived with our efforts to save humanity. Because if we’re going to talk about [how] to enlist humanity to save the planet, we have to tap and show humanity how these things are all connected.” Through his foundations in environmental justice, Mair understood that, to truly combat environmental degradation, the environmental movement must enlist people from historically oppressed, disinvested, and environmentally polluted communities.

Similarly, for my own community’s fight against environmental racism in the Inland Empire, vast populations of local community members must be mobilized to combat a multi-billion dollar corporation’s toxification of the region. Exploring Mair’s insights helped me realize how efforts in my own community require an intersectional approach of labor justice, environmental justice, and racial justice. Building enough pressure to combat the Inland Empire’s warehousing boom demands solidarity against the leading drivers of inequity and vulnerability. Although local community members will lead the fight, we must also enlist wider populations from a diversity of disciplines, localities, and demographics since the climate implications of Amazon’s warehousing boom also impacts our environment on a much wider scale. Amazon’s 2019 carbon report revealed that the global corporation “emitted 51.17 million metric tons of carbon dioxide last year,” an increase of 15% from 2018. I expect those numbers to rise even further due to the shipping boom brought upon by the global pandemic.

My reading of Aaron Mair’s oral history reiterates how radical change that finally prioritizes the well being of people and the natural world requires a wide range of collaborations between stakeholders on a wide scale. The mainstream environmental movement, the environmental justice movement, the labor justice movement, and the racial justice movement must learn to overcome ideological divisions, embrace their intersectional interests, and take unified action against structural trends that inherently create inequitable and unsustainable conditions. As Mair said, “The mutuality of all of us, depending upon all of us, our survival is dependent upon our neighbors. It’s dependent upon all the creatures, all the things within this planet. But our stewardship of those relationships, we don’t have the luxury to hate our brother, hate our sister. We don’t. And we don’t have the luxury to destroy and deplete all the ecosystems, because at the end of the day it is humanity that’s in the balance.”

I hope my curriculum development for this URAP project will contribute to education that expands minds and inspires change. For too long, people of color have been excluded from meaningful participation in environmental issues that directly impact the health of their children, families, and communities. By empowering and uplifting the voices of people who have often gone unheard, I hope we can more effectively come together as equitable stakeholders and participants in the movement for a more just and sustainable world.

Stars and Scars: A Historian’s Lessons from 9/11

by Christine Shook

Christine Shook is an independent historian with over a decade of experience in oral and public history. She earned her master’s in history from California State University, Fullerton in 2010. Her previous positions include Museum Assistant at Mission San Juan Capistrano, Exhibits and Collections Associate at the Tahoe Maritime Museum, and Historian and Assistant Vice President at Wells Fargo’s Family & Business History Center.

September 11, 2001 was an incredibly surreal day. Never a fan of mornings, I awoke late on the Pacific Coast, turned on the TV, and found some sort of devastation unfurling in the east. I didn’t know what had happened. The newscasters had temporarily moved on from the footage showing the planes hitting the World Trade Center and were instead discussing the rescue efforts and fears that the buildings surrounding the towers might collapse. Terrified and utterly confused, I turned to the Internet for answers and first saw the footage of the second plane hitting the towers, and learned about the four planes that had crashed. I spent the next hour bouncing back and forth between the computer and the tv in an attempt to discover what I missed while staying on top of the latest events. It felt like one of those days when the rest of the world should have paused while this thing worked itself out, but that wasn’t the case. I had to go to work. I tamped down the overwhelming feeling of uncertainty I was experiencing, put on my work uniform, and prepared to face the public.

As a recent high school graduate, I worked the closing shift as an attendant at a swanky hotel spa in Dana Point, California. The spa was relatively empty that day. The only exception was a couple from New York who found themselves stranded in Southern California. Unable to fly home or contact any of their friends and family, they came to the spa hoping to find a much needed distraction from the things they could not control. They didn’t stay long.

Later that night, the rest of the spa staff and I spent the hours until closing in one of those drab back rooms that only hotel staff sees, adjusting the antenna on a radio so that we could hear the latest news. As I sat listening to the radio waiting for updates about these attacks on 9/11, my mind transported me to sixty years in the past to the attack on Pearl Harbor. I began to wonder if Americans in 1941 also experienced this atmosphere of angst, remorse, anger, and uncertainty. The events of December 7, 1941 led to years of war and sacrifice. Was that where we were heading?

I was not the only one pillaging the past in search of answers about an uncertain present. Politicians, pundits, pastors — everyone seemed to be making the same comparison to Pearl Harbor, and deriving strength and certainty from the virtue with which America responded to that particular wrong. A common message seemed to be: History has taught us that America is good, so our response will follow suit. Of course, I knew from the stories of family and friends that things were more complicated than that. My grandfather earned medals for his participation in WWII but no one in my family has them today. The physical and psychological wounds with which he returned inspired him to throw those medals into the Atlantic Ocean upon receipt. As a grad student in history, I read Stud Terkel’s “The Good War” and discovered more stories like my grandfather’s that casted doubt on the flawlessness of the conflict and the glorified way in which Americans remember it. The United States’s response to 9/11, the realities of war, and the uncertainty of government actions have similarly affected people in a variety of ways over the past twenty years. While the exact failings of the response to that day vary according to political parties, few think that the United States has handled things with the storied righteousness with which it started.

My own observations and lessons about 9/11 over the past two decades have been heavily influenced by my work as a historian. For the past six-and-a-half years I helped ultra-high-net-worth families examine their historic roots in search of values and lessons that they could apply to today — using the past to guide future choices and investments. When I first began this work, the message we offered clients was always one of hope: your family not only survived X, it eventually thrived financially. There’s value to that narrative of resilience, of course, but also a danger in overconfidence. In the past few years, I’ve noticed a promising trend where family members — especially those from younger generations — want to know more and more about the hard and uncomfortable truths from their past. They appear to recognize their ancestors as flawed people with cautionary tales that accompany the celebratory.

I can only hope that this willingness to look at cherished personal histories with a critical eye will expand to include the national narrative. Perhaps the next time America faces another crisis like 9/11, the stories of people like my grandfather, who rejected a jingoistic narrative, won’t be overlooked in order to provide quick answers to the question: what now?

9/11: An Oral Historian’s Personal Recollection

by Shanna Farrell

My memories of Tuesday, September 11, 2001 are vivid. I was sitting in my second period senior English class when my teacher, who was known for his sarcasm, delivered the news.

“Hi, everyone,” he said. “I just heard that a plane hit the World Trade Center.” The class began to laugh awkwardly.

“No,” he said. “I’m serious. I don’t have any more information than that.”

A hush fell over us, but we proceeded with class as normal. I’m sure I was distracted but we were discussing books and I love discussing books. Besides, it wasn’t yet real.

When the bell rang, I walked down the hall to my current events class, where our teacher routinely had a TV playing in the back of the room so he could watch the news while he taught. That’s where I first saw the images of the plane crash. Of the burning buildings. Of people falling through the sky. Of endless smoke. Of the clear blue sky. That’s when I realized I needed to call my mother, immediately. The tragedy was now real to me.

Despite the fact that my family’s residence at the time was in upstate New York, in a small mill town built on the banks of the Hudson River that hugged the Vermont border, my mother worked in New York City. She was in educational sales and her territory covered all five boroughs. She often had appointments at Stuyvesant High School, a building that is just blocks away from the World Trade Center. I knew this because even though my birth certificate indicates something different, I was partially raised in the city. My mom would often point out Stuyvesant High School when we would drive down the West Side Highway or walk around TriBeca or buy tickets for Broadway shows in the atrium of the World Trade Center. That morning, she was on her way there.

As soon as I reached the main office of my school, I pleaded with the administrative staff to let me use the phone to call my mother.

“My mom is there. My mom is there,” I repeated. I remember the horror wash over their faces, how one of them picked up the phone and instantly dialed “9” to get me an outside line. Since my mother spent so much time in her car, she had a hard-wired cell phone, cord and all. I punched in her number, but all I got was a busy signal. I did this over and over with the same results. I called my dad and the first thing he said to me was, “I can’t reach her either.” He promised to call me as soon as he heard from my mother. I hung up the phone and turned to see a few others in line behind me waiting their turn to call family or friends who also lived in the city. I didn’t know what else to do but return to class and watch the news on loop.

I’d felt fear watching major events unfold in the past, like six years earlier when a terrorist blew up a truck bomb in front of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. That had scared me. But this fear, the type I felt while waiting to find out if my mother was alive or dead, was something entirely different. It was panicked and unrelenting. Time seemed to stand still. I could have moved from room to room or stayed in the same seat. (I do, however, remember relocating to the cafeteria at some point where TVs had been wheeled in so we could watch the media coverage.) And then I heard my name over the PA system. I had a phone call and needed to report to the office.

“She’s okay,” my dad said. “She called me from a payphone. She was in Brooklyn.”

In the days that followed I would learn that my mother was headed to Manhattan from Brooklyn that morning, but got stuck on the Brooklyn Queens Expressway while she was en route. Traffic moved slowly, if at all, and she ended up snaking her way to the part of the expressway that is just under the Brooklyn Heights Promenade, a place known for its iconic view of the lower Manhattan skyline. From there, she watched with hundreds of others as the towers burned and debris floated across the harbor as the wind blew southeast. She was eventually able to make it to Queens, where she pulled over and found a payphone. I would later watch her struggle with what she had seen that day, hear her plead with me not to get on a plane in the coming weeks for a college visit, listen to her talk to colleagues and discover she knew people on the plane that crashed into the Pentagon.

The trauma of the event was lasting for her, for me, and for us as a family. We visited Ground Zero many times and I have memories of the smoldering ashes fading into piles of debris and later becoming a gaping hole in the ground. I remember the photos of the missing people stapled to the fence surrounding the site. I remember the tone of the city and the feeling of community. I remember being so happy that my mother was alive, and so sad that others hadn’t been as lucky. I remember how filled with grief each anniversary of the attacks were each year.

In September 2011, I was starting a master’s program in oral history at Columbia University. The Columbia Center for Oral History Research had started a massive interviewing project ten years earlier, the same day the towers fell. Interviewers–staff, student, and volunteers alike– recorded hundreds of life histories with a wide range of people who were affected by the attacks. They interviewed anyone who wanted to participate and returned to many months later to interview them again. I still consider this to be an innovative model for an oral history project, especially in a field that is constantly asking itself “how soon is too soon?” (For more on this, check out Amanda Tewes’s piece on interviewing around collective trauma.)

This project served as much of the foundation of the Columbia program and the interviews became the basis for a book, After the Fall: New Yorkers Remember September 11, 2001 and the Years that Followed, which was published as I began the Master’s program. As graduate students, we read through transcripts, listened to interviews, engaged with theory related to memory and trauma-informed narratives, learned methodology for approaching sensitive interviews, and expanded our studies into other topics, like genocide and mass-incarceration. We even watched a professor interview a paramedic who had been at Ground Zero that day, live in class, offering us the opportunity to practice our question-asking skills.

It was intense. But it made me into an interviewer who isn’t afraid to shy away from difficult topics. My training also gave me space to process my own grief around the 9/11 attacks. I found myself asking my parents more about that day and how they felt in the years that followed. It gave me a concrete example around which to center my work as an oral historian and how I should approach trauma in my own interviews. How would I want to be asked about these things? How would I feel if I cried in an interview? How would my tone, pace, and velocity of speech change when a difficult subject came up? What were my boundaries and how would I express them to an interviewer? Which of my memories were solid and which were porous?

In the conversations that I had with my parents after the tenth anniversary of the tragedy, I realized that many of my memories, no matter how vividly I remember that day, were not quite accurate. My mother explained that she hasn’t actually been heading to Stuyvesant High School. Instead, she was trying to get to a school on W 33rd Street through the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel, which enters Manhattan just south of the World Trade Center. This had been part of my narrative for years. My memory wasn’t perfect.

Now, twenty years later, I’m still using these experiences as the basis for how I approach trauma-centered narratives, and, for that matter, any interview where a sensitive subject comes up. It’s remarkable how much I use the same techniques that I learned in grad school, honing them over the past ten years. My pace, my tone, my body language, my ability to pause and give someone space, my interest in putting my feelings aside to privilege a narrator’s story all matters. As oral historians, we often take the life history approach, which can dredge up painful memories from the past, no matter how much we prepare in the pre-interview and planning process. I have to be ready to handle a narrator’s emotions about a troubled relationship with a parent, a divorce that proved formative to a career, a bad review in a newspaper, and yes, a terror attack.

It’s also made me mindful of people’s memories, especially around trauma. Though the historical facts of how I remember 9/11 remain static for me, the details of my mother’s experience were fuzzy. But it’s relevant to how we memorialize events, how we talk about them with our own communities, and what gets documented in the historical record. It’s also made me consider what gets left out of the left out of the story, perhaps because it happened too long ago, was repressed, or doesn’t feel as significant. For example, in talking to my mother about this very article that you’re reading, she told me that I was interviewed by the local newspaper shortly after September 11, 2001 about my experiences that day. I had my picture taken. I said that 9/11 had “changed my life.” Yet, I have no memory of being interviewed until or having my picture taken. And I have no idea why. I only vaguely remember hearing my parents talk about the article. In many of the oral history interviews that I’ve conducted over the last ten years, narrators often say to me, “I can’t remember the last time I thought about this.” That’s exactly how I felt when my mom told me about that newspaper article.

9/11 shaped me in countless ways. That cloudless Tuesday and its aftermath continue to be present in my life, following me from high school to graduate school to my work at the OHC. It’s informed the way I think about life pre-9/11 and over the past twenty years. I’m not sure my memories will ever be less vivid or more pliable, but the impact, personally and professionally, will persist.

9/11 and Interviewing around Collective Trauma

“…I very rarely ask questions about 9/11 during oral history interviews, and I’ve been trying to grapple with why that is.”

As we approach the twentieth anniversary of 9/11, I’ve been reflecting on my own memories of that fateful day in September, and its impact on how I interview others about traumatic events. Indeed, I recently realized how deeply intertwined my thoughts about 9/11 are with my oral history practice.

The first time I spoke aloud about 9/11 – aside from discussing breaking news in the days that followed – was in my introductory oral history class with Dr. Natalie Fousekis at California State University, Fullerton in August 2009. This was nearly eight years after the original events, when the terrorist group al-Qaeda coordinated the hijacking of four passenger airplanes with the intent to crash them into major US targets. This led to a tragic loss of life and shook a sense of national security for many Americans.

As an exercise about collective memory, Natalie invited the class (from youngest to oldest) to share recollections of that day. Despite the age differences (approximately early twenties to early forties), as we went around the table, it was striking that roughly twenty different stories aligned so closely, as though we were all reciting the same narrative with slightly different words. With the exception of hearing the news while getting ready for high school, my own memories were much the same. This was, of course, in part due to the media coverage Americans saw of the Twin Towers falling over and over again, which helped create a collective memory of that day. But the similarity in omissions was striking, too. I don’t remember many people discussing the plane that hit the Pentagon or Flight 93, which crashed in the fields of Pennsylvania. Later dubbed Ground Zero, even in 2009, New York City dominated our memories of 9/11.

I also remember that though the mood in the classroom was somber, none of us cried or expressed an overwhelming sense of grief. Looking back, I wonder why there wasn’t more emotion around this discussion of such a traumatic moment. The eighth anniversary of 9/11 was only weeks away, and for those who had been teenagers in 2001, that day and the ensuing War on Terror had indelibly changed our lives. In part, maybe we were already trying to analyze our own experiences as oral historians rather than vulnerable individuals, interpreting what our collective memories meant rather than sitting with their personal heaviness. Or maybe this room of California students felt more removed from the horrors of that day due to physical distance from the sites on the East Coast. But it is also possible that even eight years later, we weren’t yet ready to address these memories as collective trauma.

In the more than a decade since this classroom discussion, I have conducted hundreds of oral history interviews – many of them discussing traumatic moments for individuals and the collective. Yet, I find it strange to reflect on the centrality of 9/11 to my early oral history training, as it has been a major pitfall in my own practice as an interviewer. About three years ago, while preparing an interview outline, I suddenly realized that my narrator’s work documenting and securing collections at a major arts institution coincided with this moment in history. Luckily the narrator agreed to share her memories, and we had a fruitful discussion about the ways in which, for a time, 9/11 impacted all levels of American culture. This experience helped me register that I very rarely ask questions about 9/11 during oral history interviews, and I’ve been trying to grapple with why that is.

One possibility is that I, like many others in the field, struggle with when an event gets to become “history,” and how we choose to memorialize it. To me, 9/11 feels like yesterday, not necessarily an historical moment upon which I need to ask narrators to reflect. And I am certainly guilty of collapsing historical timelines and not concentrating on the recent past, even during long life history interviews.

But I also suspect that my omission of 9/11 in interviews has a great deal to do with the traumatic nature of that day. Like many interviewers, I’ve sometimes been reluctant to introduce topics at particular points of an oral history for fear of creating a trauma narrative where there otherwise wasn’t. And until recent training, I was not even confident in my own skills tackling trauma-informed interviews. This hurdle has a clear solution: I need to prioritize discussing potentially traumatic topics like 9/11 in pre-interviews or introducing them in the co-created interview outline.

What is less clear is how to navigate my own trauma about 9/11. How do my own memories of that day impact my willingness to ask others about it? Am I too close to the subject to be able to speak with narrators about it? Quite possibly. But one complication for all interviewers is that unlike other traumatic events with a beginning and end date, 9/11 is an ongoing reality – even twenty years later. From the recent withdrawal of US troops from Afghanistan to the wide reach of the Department of Homeland Security to heightened airport screenings, we are all still living with the consequences of 9/11, and the trauma has not actually ended.

Twelve years after that classroom exercise around 9/11 and collective memory, I can appreciate Natalie’s methods all the more. I’ve learned over the course of my oral history practice that even deeply personal narratives can include elements of collective memory, and it is important to recognize such common threads in our lives as interviewers, as well.

I often preach that oral history practitioners need to acknowledge our biases so that we can better overcome them or even use them to our advantage. For me, examining my blind spot around 9/11 has also encouraged me to think about incorporating more recent and ongoing historical events into interviews. Not only is this reflection an important addition to the historical record, it is part of our essential work to help narrators make meaning of their lives through oral history. Similarly, evaluating my own blind spot around 9/11 has helped me recognize the blind spots in the collective memory of that day – such as narratives that leave out Flight 93 or the attack at the Pentagon – and encouraged me to think about how oral history can help fill these gaps. As we recognize the twentieth anniversary of 9/11, this work feels more necessary than ever.

Request for Proposals: New Oral History Symposium

Assessing the Role of Race and Power in Oral History Theory and Practice Symposium

Call for Proposals, EXTENDED DEADLINE of November 1, 2021.

Convened by the Ad Hoc Group for Transformative Oral History Practice in collaboration with the Oral History Association and the Oral History Center at UC Berkeley

It has been just over one year since a White police officer murdered George Floyd, sparking the largest call for racial justice in this country in a generation. Support for Black Lives Matter reached an all-time high in June 2020, with nearly 70 percent of U.S. adults holding a favorable opinion of the movement, and support spilling over to all corners of the globe. White Americans also helped take down Confederate monuments and bought books on antiracism in record numbers while corporations pledged millions of dollars to social justice organizations and causes. One year later, however, commemorations of Floyd’s life and legacy asked: “What’s changed since?”

We acknowledge that “Assessing the Role of Race and Power in Oral History Theory and Practice” is taking place amid revitalized demands for understanding – and changing – the systemic racism that enabled a White police officer to murder a Black citizen in daylight without seeming fear of repercussions. But it is also taking place at a time of fierce backlash to any understanding of the oppressive forces that enabled Floyd’s murder. At the time of this writing, some state legislatures have passed laws banning the teaching of critical race theory, even as a majority of states seek to suppress the Black vote and overturn our elections. Recent events such as these are causing many to evaluate the role of structural racism and White supremacy in the arts and humanities, including the practice of oral history.

Building on an enthusiastically received panel that asked “Is Oral History White?” at the 2020 Oral History Association annual meeting, participants in that session (calling ourselves the Ad Hoc Group for Transformative Oral History Practice), in collaboration with the Oral History Association and the Oral History Center at UC Berkeley, are convening a symposium that will define, identify, analyze, assess, and imagine alternatives to conventional practices, prevailing ideologies, and institutional structures of oral history in the United States and Canada, as they pertain to historic and current forms of systemic racial discrimination. In essence, the symposium is moving beyond the question the 2020 panel asked – “Is Oral History White?” – to interrogate broader structures and dynamics of race and racialized thinking in oral history.

We are inviting proposals from oral historians and others involved in fieldwork-related interviewing practices, as well as critical race and Whiteness theorists, to submit proposals for symposium papers that pose major questions and offer precise assessments of racial constructs as a factor in all phases of oral history work: project design, research processes, financial and budgetary matters, fieldwork and community relations, interviewing, archival practices, and public presentation and interpretation of narrative materials.

The “Assessing the Role of Race and Power in Oral History Theory and Practice” symposium will take place via Zoom Webinar over a three-day period in June 2022. We expect to convene approximately thirty-five presenters, spread over six to eight sessions of two hours each. With the assistance of a moderator and/or one or more discussants, session presenters will summarize and discuss pre-circulated papers posted on a conference website, which will have also been made available to registered attendees in advance of the symposium. Symposium sessions will allow time for audience questions and comments, vetted and synthesized via the Zoom Webinar “Q&A” function by the session moderator. This format will allow for especially robust and probing discussion during sessions.

This symposium should present a significant opportunity for audience members to reflect personally upon the charged subject of race in oral history in a pedagogically constructive way. Discussions of racialized experience and representations in our field will raise not only important insights but also strong emotions. We expect our audience to have a vast range of racial identities and relationships – including but not limited to Whiteness and Blackness – and varying degrees of experience reflecting upon that. We therefore plan to set shared expectations for constructive conversation rooted in mindful awareness, good faith engagement, and emotional maturity at the very beginning of the symposium and to create opportunities for small-group discussion and individually tailored self-reflection over the duration of the symposium. We hope that the symposium’s virtual nature, with participants in the relative privacy and comfort of their own homes, will contribute to this aspect of the symposium experience. Above all, we plan to keep discussion focused on practical applications of whatever theoretical and conceptual insights into race in oral history our symposium may furnish.

Intended outcomes include publication of revised versions of selected conference papers in an edited volume and a white paper assessing OHA’s racialized history, practices, and programs, to be developed by symposium organizers. Organizers, in cooperation with OHA’s Equity Task Force and Diversity Committee, will also create and promulgate guidelines for racial equity in oral history.

Pending receipt of grant monies, we hope to provide honoraria for symposium presenters.

Proposal Information

Each proposal should include a title, an abstract of no more than 500 words, and a short biographical statement of no more than 300 words. Include your name, institutional affiliation if relevant, mailing address, email address, and phone number. The abstract must outline the research that you either have conducted or intend to conduct in support of your proposed presentation, the sources that you have consulted or will consult, and the collections in which you have conducted or will conduct research. While we anticipate that most proposals will be for a single paper, we welcome proposals for full sessions, also – to include 3-5 papers, moderator and discussant/s. We also welcome inquiries from individuals interested in serving as a session moderator or discussant to include a brief statement of interest and a short summary of work in oral history. Proposals are due October 1, 2021. (See below for more information.)

Some questions and themes we expect symposium participants may address include:

(Please note that we are open to other related questions and explorations.)

Whiteness and White Supremacy

- How should Whiteness be defined, and how do the deep structures and conventions of our practice reflect Whiteness, structural racism, and White supremacy?

- How might an interrogation of unexamined Whiteness be brought to bear on work in oral history? This might be done by assessing a past project or the curation of an existing collection or by considering the planning and implementation of a project currently under development. (Note: While we welcome case studies that audit specific projects, we would also like to see papers go beyond that.)

- How has work that has drawn upon existing collections reproduced racialized assumptions?

- What are some examples of projects that handled or represented racial dynamics, including Whiteness, in a creative, antiracist, or otherwise generative way?

Non-Western perspectives and approaches

- What has oral history learned from Indigenous, African American and other perspectives and approaches that fall outside the dominant Western paradigm?

- What patterns do we see in our own work that can be traced to BIPOC origins and models? What do these BIPOC origins and models have to teach us about the pitfalls of Whiteness and White Supremacy?

- How might specific insights, both theoretical and methodological, generated by the field of Critical Race Studies, help guide practical approaches to oral history?

- How and in what circumstances has oral history operated against the grain of prevailing racial assumptions?

- What can oral historians learn about power dynamics and reflexivity from research in the field of trauma studies?

Invisible Architecture

- How have the institutional and organizational structures underlying work in oral history been racialized? How has the way oral history has been funded and otherwise supported contributed to unintentional racial bias? How has the “history from below” approach perpetuated these biases? And how do White interviewers themselves perpetuate bias?

- Over its fifty-plus year history, how has the work of the Oral History Association been racialized or reflective of broader patterns of White supremacy? In what ways and to what effect has the association functioned as a gatekeeper for oral history and oral historians, including some practitioners, practices, and work, excluding others, through its various products and programs such as the Principles and Best Practices, annual meeting, and publication of the Oral History Review? How has the association addressed racial issues over time, to what effect?

- When and where is it appropriate for oral historians to think beyond our individual projects and consider the role of the institutions we work for in order to tackle structural racism?

Oral history and current events

- How are oral historians and the institutions and organizations with which we are affiliated responding to the current political moment? How might we respond more effectively?

- Oral history is by its nature a civic enterprise and a medium for public engagement. How can oral history mobilize anti-racist constituencies, create dialogue around difficult issues, and/or influence public opinion or policy?

- What are the limits of oral history in combating structural racism?

The deadline for proposal submissions is October 1, 2021.

Notification of acceptance: On or about November 15.

Submit proposals to:

In the subject line of your email, please write, “Last Name Symposium Proposal Submission” and send to: TRANSFORMATIVEORALHISTORY@GMAIL.COM. Proposals should be sent as an attachment in Word or PDF formats and not in the body of the email. Please include a cover page with your name, contact information, and brief bio.

Questions may be directed to:

TRANSFORMATIVEORALHISTORY@GMAIL.COM

Final papers should be submitted no later than April 15, 2022 in order to post them on the conference website for distribution to conference attendants by May 1, 2022.

Final papers should be between 5,000 and 7,000 words and include a bibliography.

Submit final papers to:

In the subject line of your email, please write, “Last Name Symposium Paper Submission” and send to: TRANSFORMATIVEORALHISTORY@GMAIL.COM. Proposals should be sent as an attachment in Word or PDF formats and not in the body of the email. Please include a cover page with your name, contact information, and brief bio.

*The Ad Hoc Group for Transformative Oral History is composed to date of the five panelists who contributed to the OHA’s 2020 conference session, “Is Oral History White?” – Benji de la Piedra, Jessica Douglas, Kelly E. Navies, Linda Shopes and Holly Werner-Thomas.

From the Oral History Center Director — July 2021

From the Oral History Center Director — July 2021

I recently had the pleasure of watching a new documentary film, The Sparks Brothers (2021), which details the solidly unconventional musical career of Ron and Russell Mael, lifetime stalwarts of the band Sparks. This film has everything one might want from a rock and roll documentary: rare footage of live performances, insightful commentary from artists influenced by the band (Beck, Bjork, Weird Al), and a narrative charting several artistic ups and downs. You might watch it and think that you caught an episode of “Behind the Music” (without the cliche visits to Betty Ford) or This is Spinal Tap (the new wave remix). But the thing about this film that really caught my attention — and got me thinking about our work at OHC — is how revealing and edifying a full life history can be (as is done with The Sparks Brothers as well as with many of our oral histories).

Growing up in California in the early 1980s, Sparks originally came to me as another hip, ironic, proudly nerdy Los Angeles new wave band. Surely the first song of theirs I heard was “Cool Places,” an absurdly upbeat synthpop song performed with and co-written by Jane Weidlin of the Go-Go’s. I saved my pennies and soon purchased the album (Sparks in Outer Space) and loved most every song. I followed their career through another few albums then, as teenagers do, moved on to other bands and sounds. To me Sparks remained in my memory as a genre-band — a very good one, but still one of a particular type.

Watching this full-life documentary, however, upset my own memories of this band. It revealed parts of their lives (including telling moments of their childhood) that were unknown to me. It showcased their early years as a Zappa-like freak band, their move to England where they earned fans as glam-rockers, their burgeoning interest in synthesizers and ultimately their collaboration with synth-god Giorgio Moroder, and finally their return to Los Angeles and reincarnation as a new wave band. The film also details the years since the 1980s, which took the pair in even more esoteric musical directions while continuing to win new fans, garner critical accolades, and stage frankly amazing artistic achievements. After watching this video, I am now eager to dig deeper into their music and thus discover bits of pop music past that thus far had been hidden to me. New music need not emanate from this day and age after all.

This is one of the reasons that I think the life history interviews we do at the Oral History Center are so incredibly valuable. When we conduct this type of oral history (ten hours or more with a single individual) we not only have the opportunity to ask the obvious questions (“tell me about the research that led to your Nobel Prize?” “What was it like to win at the Supreme Court?”), we are afforded the freedom to explore the lesser known aspects of a narrator’s life. With the additional hours of interviewing, we can document the narrator’s family background, upbringing, and education. We can detail early career moves that maybe didn’t amount to much but which taught crucial life lessons. We can document failures as well as successes. In my interview with Herb Donaldson, the first gay man appointed as a judge in California, I also learned about his side job as a coffee importer and roaster who gave key advice to a certain coffee shop getting started in Seattle (yes, Starbucks). With former Kaiser Permanente CEO George Halvorson, I got a fascinating account of his establishing a new health system in rural Uganda. And in my in-progress interview with famed Newsweek and Vanity Fair reporter Maureen Orth, there’s a lengthy description of her two years in the Peace Corps. While perhaps not what these people are best known for, these “other projects” not only provide great insight into the individual but often offer useful insights into historical events. Sometimes you think you know the whole story, or at least the most important part of that story. But when you read — or conduct — life history interviews, you soon learn that all parts are important and those less regarded can be the most surprising.

In this spirit of uncovering less known accomplishments, I want to pay tribute to Bancroft staff who recently retired. At the end of June we witnessed the departures of Bancroft Director Elaine Tennant (also a renowned scholar of German literature and culture), Deputy Director Peter Hanff (also a recognized expert in all things Wizard of Oz, which he detailed in his oral history), finance manager Meilin Huang (also the savior of the Oral History Center on many occasions), and photographic curator Jack von Euw (also an excellent curator of many Bancroft exhibits). We bid farewell to these four esteemed colleagues. We hope that retirement adds several new and interesting chapters to already very accomplished lives.

Find these and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.

Martin Meeker, Charles B. Faulhaber Director, Oral History Center

Charles Gaines: The Criticality and Aesthetics of the System

As a continuation of our work for the Getty Research Institute’s African American Art History Initiative, Dr. Bridget Cooks and I conducted a series of oral history interviews with the conceptual artist Charles Gaines. This interview was the first of several exploring the lives and work of Los Angeles-based artists, and celebrates Gaines’s extraordinary artistic contributions.

Charles Gaines is an artist specializing in conceptual art, as well as a professor of art at California Institute of the Arts. Gaines was born in South Carolina in 1944, but grew up in Newark, New Jersey. He attended Arts High School in Newark, graduated from Jersey City State College in 1966, and earned an MFA from the School of Art and Design at the Rochester Institute of Technology in 1967. Beginning in 1967, he taught at several colleges, including Mississippi Valley State College, Fresno State University, and California Institute of the Arts. Gaines has written several academic texts, including “Theater of Refusal: Black Art and Mainstream Criticism” in 1993 and “Reconsidering Metaphor/Metonymy: Art and the Suppression of Thought” in 2009. His influential artwork includes Manifesto Series, Numbers and Trees, and Sound Text; and he exhibited at the Venice Biennale in 2007 and 2015. Gaines is the recipient of several awards, including Guggenheim Fellowship in 2013 and REDCAT Award in 2018. Find this interview and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.

Hearing about Charles Gaines’s upbringing was especially helpful in framing his approaches to art. For example, he spoke about his mother’s influence on his life–particularly her musical inclinations. Though Gaines concentrated his early artistic studies on the visual arts, he also had a passion for music, eventually becoming a professional drummer. This connection to musicality and music theory features prominently in his conceptual works like Snake River and Manifestos. Indeed, in his Manifestos Series, Gaines turned the text of political manifestos into musical compositions based on a system he devised. He recalled, “Unconsciously, I began thinking about music as a kind of mathematics and this connection with text and language; I began to see the connection to language and systems.”

speakers, hanging speaker shelves. Photograph by Frederik Nilsen.

Further, Gaines shared about his exploration of conceptual work in the 1970s, and his consequential transition from an abstract painter to a conceptual artist:

Well as I said, those big abstraction paintings turned into these process-oriented works, and so that work demonstrated an interest in a systematic approach. It was a part of my research. I was looking for an alternate way of making work that was not based upon the creative imagination, was not based upon subjective expression.

This transition period also coincided with an eighteen-month sabbatical from teaching at Fresno State University from 1974 to 1975, when Gaines, his wife, and infant son moved to New York to explore his professional art practice. He recalled of the conceptual artists he met there:

But I did at that time, during that time in New York, become much more familiar with conceptualists, with what the conceptualists were doing. At that time, it provided a context for me. It was just before I started working with numbers but I was working with systems already, and so I felt that it’s true that, of anybody, my work, the language of my work fits best with those conceptualists.

Another major theme in Gaines’s interviews was his many years teaching art at colleges across the country, including the challenges of teaching at what he deemed conservative institutions. Despite these challenges, Gaines always looked for ways to mentor his students by not only helping them improve the quality of their work, but also by sharing his own insights into how to navigate the art world. He explained:

The thing I would always give my students advice about is that you can’t control career. That’s something that you shouldn’t even be thinking about. You should only think about the work, and you should also think about exhibiting the work, which I think is different from a career. You need to show people the work, so you make the work and try to get people to see it. In that process, something might happen, you can’t make it happen. In almost every story about how careers get kicked off, it’s because you happen to be at a right place at the right time, and somebody who matters notices something, and then things sort of roll into place…Ultimately, it’s the work that’s going to get you the exposure.

In addition to his own works and teaching career, Gaines has also made many important contributions to the art world through his theoretical writing and curation of exhibitions. In 1993, he co-curated Theater of Refusal: Black Art and Mainstream Criticism with Catherine Lord at the University of California, Irvine in 1993. This show, and Gaines’s catalog piece, explored racism in the art world by displaying Black artists’ work alongside reviews from (largely white) art critics, and questioned how and why they misread this work. Of this important exhibition, Gaines explained:

Well, I chose artists who were actively producing in the art world, and known to people. In a couple of cases, I showed a couple of people who were at an early part of their career, like Renée Green, for example, just started her career. But there were other people like Lorna Simpson and Fred Wilson, Adrian Piper, were completely well-known. The fact that they’re well-known artists was important to me because it allowed me to underscore this point that I was making: that is that there’s not much writing on the work of artists, even if they’re well known. The writing that there is [is] marginalized around the idea of race. The writers who wrote about [them] often thought they were writing positively about the work. They didn’t think that the way they approached the work was, in fact, marginalizing.

To learn more about Charles Gaines’s life and work, check out his oral history interview! Find this interview and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.

From the OHC Archives: Zona Roberts and Learning to Walk Backwards

by Annabelle Long

Annabelle Long is an Undergraduate Research Apprentice at the Oral History Center. She worked with Shanna Farrell during the Spring ’21 semester. Annabelle is a third-year History and Creative Writing student from Sacramento. She works as a conduct caseworker in the Student Advocate’s Office and enjoys going on long walks in Berkeley. You can find her on Twitter @annabelllekl.

The pocket of Berkeley bounded by Telegraph and Shattuck avenues is generally considered to be quiet and uneventful. Colorful Victorian houses line the blocks, gray apartment complexes full of Cal students loom over sidewalks, and telephone lines crisscross over each other, dividing the sky into irregularly sized rectangles and diamonds. I spend a lot of time in this part of Berkeley. I have my favorite houses, my favorite trees, my favorite views in every direction. I have my favorite alleys and blocks and moments in its history. I can’t pick a single favorite former resident, but Zona Roberts is high on the list.

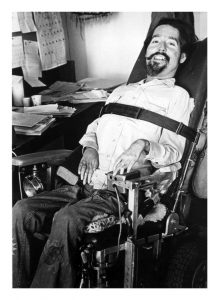

Zona existed in Berkeley as a mother before she existed here as a student. She lived with her sons Ed, Ron, Mark, and Randy in a pale green house she rented on Ward Street, a few blocks west of the hustle and bustle of Telegraph Avenue and a few blocks east of Shattuck. I often walk by her old house. It’s blue now, with red front steps, and it sits unassumingly behind a fence overgrown with flowers in the springtime. When Zona moved in, she had a ramp installed in the back to allow Ed to get inside. Ed Roberts, Zona’s eldest son and a political science major at UC Berkeley, was the first wheelchair user ever admitted to the school, and virtually nothing in the city was wheelchair accessible when he arrived on campus in 1962, including his mother’s home.

Ed Roberts

The green house, as it came to be known, acted as a sort of safe haven for the Roberts family and their friends. It was a family home for the community, not just Zona and her sons.

“It was a neighborhood of older families who’d lived there, a neighborhood of single-family homes, mostly, or two flats,” Zona said of the area, “The neighborhood was just changing as some of the older folks were dying off and some were moving away. A few younger people were moving in, but it was more or less an established neighborhood. But because of the racial composition and students in Berkeley, no one cared who went in and out of my house. The kids who came in or the Black students who visited and some lived, for a while, with me. There was no threat to their lives. There were none of those issues. It was just like a breath of fresh air to me. It was so nice not to have to worry about what might happen. I remember that vividly.”

Roberts Family

Zona, by all accounts, was an unflappable person. When she and her sons came to Berkeley, she was a recent widow, and had been Ed’s primary caretaker since he contracted polio and became a quadriplegic in 1953. She was a fierce advocate for all her sons and their needs and disliked being told what to do—she, as a learned expert in their likes and needs, felt that she knew best.

UC Berkeley promised a new world of opportunity for both her and Ed, when previously, his disability had meant neither of them was optimistic about what the future would hold, and her role as mother and caretaker left little room for imagining a life outside their home. But Berkeley was different; here, Ed was a student and leader, and eventually, so was she. In her oral history, when the conversation veered away from her time in Berkeley, she’d direct it back with references to the green house. The landscape of her college experience seemed to define it. She became acquainted with Berkeley alongside and behind Ed.

“One of the first days when I had taken Ed across and through campus, he was in a pushchair those days. He was quite tall and quite thin. We were going down into Faculty Glade and I had a hold of the back of his chair. It began to slip a little bit and I ran into a tree sort of deliberately to stop the chair, just the side of it, into this tree because I felt I was going to lose it. I don’t know whether my hands were sweaty, or the place was wet or what was happening. I think I finally learned how to do it backwards, where I’d walk down the hill backwards. I had better control.”

This anecdote, in my mind, speaks to the essence of Zona Roberts: ever present and adaptable to the needs of her son, caring and thoughtful, in the heart of Berkeley.

“In my senior year, I’d visit Ed up at Cowell. I remember one of the first times I walked through campus carrying my books, walked by Strawberry Creek, walking up to Cowell instead of coming in the station wagon from home or coming over to visit them. Here I was walking across campus on my way between classes and going up to visit and smiling a broad smile that I was now a student at Berkeley, also, and very proud of myself, and loving the campus and Strawberry Creek coming down through the middle of it. There’s some beauty in that Berkeley campus,” she said.

This feeling of reverence for Berkeley—for the atmosphere of casual intellectualism, for the exciting possibilities of being a student, for the sometimes-unbelievable natural beauty of the campus—is one I am intimately familiar with. I can only imagine how those feelings would be magnified for Zona, who, as a middle-aged widow and mother of four, never thought she’d live in Berkeley or become a student.

Zona was immensely proud to be a Berkeley student and to be Ed’s mother. She encouraged his involvement in activism and saw herself as an important backer of the disability rights movement; she saw herself as, first and foremost, an important backer of Ed.

“I saw my role at the office [UC Berkeley’s Center for Independent Living] as it became known as I did in Ed’s life, pushing Ed in front and being behind him,” she said of her involvement, “This was a place for people with visible disabilities to be visible, to be out in front. I found myself being in a supporting role, seeing that the office functions were going as smoothly as possible, seeing that there was food and heat and counseling and open doors and open access to information from us to the university and from the university to us. But somehow, we were in this together and it was a part of a wonderful movement. The time had come, and we were in the forefront of the movement and we were told this from all over the world. That was a glorious feeling. Hard work and glorious feeling.”

Zona Roberts

Zona Roberts worked hard to be the best mother she could be. Eventually, that meant becoming an integral part of a movement that was so much larger than any of them individually. If Ed Roberts was the father of the disability rights movement, Zona was the grandmother. She worked in the Center for Independent Living for years after its founding, and remains active in disability rights activism today, years after Ed’s death and well into her one hundred and first year of life.

I imagine the learning process of her activism was similar to learning to walk down the hill next to the Faculty Glade backwards, or modifying the old green house on Ward Street to make it accessible: sometimes slow-going, and certainly not without error, but always more than worth the trouble.

Crip Camp and Judy Heumann: Studies in Movement Snapshots

by Annabelle Long

Annabelle Long is an Undergraduate Research Apprentice at the Oral History Center. She worked with Shanna Farrell during the Spring ’21 semester. Annabelle is a third-year History and Creative Writing student from Sacramento. She works as a conduct caseworker in the Student Advocate’s Office and enjoys going on long walks in Berkeley. You can find her on Twitter @annabelllekl.

I watched the 2020 documentary Crip Camp to get a sense of Judy Heumann, the disability rights icon and architect of a movement that created a more accessible world. I had only recently read her oral history, conducted by UC Berkeley’s Oral History Center, and I was eager to learn more about the woman behind the words on the page. When she is first shown in the film, she is doing what I’ve learned that she does best: leading a group. She has a big voice and a bigger grin, and talks campers through their options for dinner later in the week. She’s already thought it through—she considered veal parmesan, but found the veal to be too expensive, so next on her list is lasagna, the suggestion of which elicits both cheers and groans from the crowd. She offers everyone a chance to make their case, and then takes a vote. Lasagna wins—barely. This vote, in its consequences, probably meant very little to Judy and very little to everyone else. But in my mind, it makes one thing clear: Judy didn’t make any decisions without considering and consulting the group. She cared what people had to say, and she listened. And so campers had lasagna, and eventually, thanks to her activism, disabled Americans had laws to protect them.

Crimp Camp provides a snapshot of the disability rights movement through the lens of Camp Jened, a summer camp for disabled children and teenagers that opened in upstate New York in 1951. Each summer, about 120 campers moved in for four to eight weeks. The camp, despite often being credited with changing the lives of its campers, had immense financial struggles and closed its doors in 1977, leaving its legacy in the hands of the many campers who passed through. Judy contracted polio and became paralyzed at 18 months old, and for every summer from ages 9 to 18, she was one of those campers. She credited her time at Jened with shaping her approach to activism and life generally.

Jened resembles the woodsy summer camps of my childhood, but it had more of a Summer of Love aura about it—the rec room was boisterous and the softball games were passionately played, but at Jened, counselors were hippies, campers fell in love, and the bunkrooms and mess halls overflowed with eager conversations about the state of disability rights and the world. It was in those conversations, Judy would go on to say, that she learned to listen to a group, lead a group, and speak as a part of a group. To Judy and the other campers, Jened was more than a camp: it was a place to be fully and truly oneself, a place to try out new politics, and often, a place to meet close friends and lovers (Judy even said she never dated outside of camp). It almost seemed sacred.

Jened is both a moment and an enduring feature in the history of the disability rights movement, and Crip Camp seeks to understand it as both: as a physical place, where people gathered and grew, and as a concept, a memory and idea that endured well beyond the summers it operated. Oral history, as a practice, seeks to accomplish something similar. It draws on memories of particular moments, the feelings that make something worth remembering, and unites those memories with broader historical narratives to give a complete picture of a life and a time. But I can’t help but wonder—what does it mean when a story continues after the taping is done? When the end of the recorded narrative turns out to be the midpoint of a real and full life?

Judy Heumann’s oral history focuses on her time UC Berkeley, where she received her master’s in Public Health, and the 504 sit-in of 1977, which she was critical in organizing. For 25 days, Judy and well over 100 disabled people occupied the San Francisco office of the United States Department of Health, Education, and Welfare and demanded enforcement of Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, which stated that no institution receiving federal funding could exclude people on the basis of their disability. Judy’s activism in 1972 was critical to getting Section 504 written in the first place, and she and other disabled people were tired of it being completely unenforced—schools, cities, and buildings were still inaccessible despite the law’s promise. Schools lacked elevators to allow disabled students to get to their classrooms; sidewalks lacked defined dips in the corners and thus often forced wheelchair users to take inconvenient, circuitous routes to their destinations or left them stranded. In response, disabled people occupied government buildings across the country in protest. The San Francisco demonstration was the longest lasting and arguably the most successful, largely thanks to the motivating force that was Judy Heumann.

Judy Heumann

In Crip Camp, Corbett O’Toole, a disabled activist and one of Judy’s contemporaries at the Center for Independent Living at UC Berkeley, said that “we were more scared of disappointing Judy Heumann than we ever were of the FBI or police department arresting us.” This was because Judy served as the central organizing force of the occupation—she held down the fort, ensured people’s needs were met (no easy task when many occupiers required around-the-clock physical assistance), and negotiated with government figures to advance the cause. I’d be scared to disappoint her, too.

There’s no debate about her status as an organizing powerhouse. In the early days of the disability rights movement, everyone in her orbit seemed to recognize that she had a knack for getting people together, getting people to listen, and perhaps most crucially, getting people to act. Mary Lester, a staff member at the Center for Independent Living spoke about Judy in her own oral history and credited her with the movement’s expansion.

“Judy was the one who brought in deaf services and was the one who always wanted to expand the population we were serving. She was pushing us in those directions to broaden the coalition. She was a networker supreme,” she said, “Judy wanted to push CIL as far as it could go in terms of being a model and being a pioneer and bringing all of the different disability factions, if you will, together.”

Judy was meticulous and thoughtful in her activism; no stone went unturned, no idea went unexplored, and no voice went unheard.

“We had the civil rights aura, but we had the facts,” she said of the Independent Living Movement, which she helped develop in Berkeley, “I mean, I think the civil rights aura without the facts actually doesn’t get you where you need to be. But the facts without the civil rights perspective doesn’t necessarily get you there either.”

Berkeley, as a city and community center, played a critical role in shaping the 504 sit-ins and the disability rights movement more broadly.

“Well, you know Berkeley is a small community, period. And many of the people certainly at that time were activists. And you lived on the same block with somebody, or a couple of blocks away,” she said, starting to laugh, “And that’s just the way it is. It’s a town.”

UC Berkeley was to Judy and her friends what Jened had been to them in their youth. Crip Camp gets at this: many of Judy’s friends from her camp days eventually made the same westward journey that she did, and ended up in and around the UC Berkeley community. There, they took the community they’d built in upstate New York and turned to activism. Jened taught them the importance of their community; Berkeley taught them how to fight for it.

Judy Heumann recorded her oral history with UC Berkeley’s Oral History Center in 2007, decades after her time at Camp Jened and some of her most well-known organizing efforts. Since then, she’s lived nearly another decade and a half—enough time to feature in an Oscar-nominated documentary, host a podcast, produce a research paper on improving media representation of disabled people, publish a memoir, and work on advancing disability rights internationally as a special advisor to President Obama in the State Department.

She spoke about her international ambitions and hopes for the disability rights movement in her oral history, before Barack Obama was even the Democratic nominee for president; before there was even an inkling that her role as his special advisor on international disability rights would ever exist. In this way, oral history provides us with a window into her mind, a snapshot of a moment in the unfinished history of the disability rights movement. This, perhaps, is part of the value of an oral history conducted before the end of someone’s life—it reveals the in the moment motivations and thoughts behind future actions, and is definitionally more than just temporally distanced reflection or speculation about how and why something occurred.

Judy Heumann at the 2021 Academy Awards

In the same way that Crip Camp sought to capture multiple dimensions of Camp Jened and its legacy, looking at Judy Heumann’s oral history in light of the more recent years of her life allows for a complex and interesting portrait of her and her accomplishments. As a history major, the people I study often never lived to see the worlds that they created, so it is especially wonderful to know that Judy Heumann saw the disability rights movement from its inception to a piece of storied history behind the world as we know it now.

“But you know, you walk up Telegraph Avenue, you go to Rasputin’s, and you see this history of the disability movement, and the owner of the store proudly displaying history of the disability rights movement on a building,” she said in her oral history, “You see, I go into a restaurant yesterday and there are two young disabled people coming in from Berkeley sitting down and having lunch together. The waiter’s moving the chairs out, and I’m like, oh, I guess two people in chairs are coming. And these things are natural now, because there is such a large number of people here that the community itself has become more accepting. It’s normal.”

I am a student at UC Berkeley and I live a block from Telegraph Avenue; between me and Judy’s tangible legacy sits a sidewalk that slopes down at the corners for wheelchair access. The world is not perfectly accessible, and there is still much to be done to ensure that disabled people’s rights are protected, but I like to think about how my normal is the product of Judy’s life’s work.

From the OHC Archives: Linda Perotti, Apolitical Advocate

By Annabelle Long

Annabelle Long is an Undergraduate Research Apprentice at the Oral History Center. She worked with Shanna Farrell during the Spring ’21 semester. Annabelle is a third-year History and Creative Writing student from Sacramento. She works as a conduct caseworker in the Student Advocate’s Office and enjoys going on long walks in Berkeley. You can find her on Twitter @annabelllekl.

Linda Perotti didn’t mean to join a movement. She arrived in Berkeley a year after the Free Speech Movement got its raucous start on the steps of Sproul Hall, the university’s now-famous administrative building on the southern edge of campus, and she was more concerned with keeping up with her coursework than with any of the growing number of antiwar and civil rights movements that would come to characterize Berkeley in the late 60s.

“[T]he thing I remember most is the Sproul steps, just sitting there and watching people go by,” she said of her freshman year. She regarded herself as an observer, never a participant. But as these things tend to happen, a movement found Linda anyway.

As a freshman at Cal, Linda was surrounded by the energy of the movements unfolding across campus. Sproul Plaza seemed perpetually occupied by someone giving an impassioned speech about any number of political issues to a crowd of eager students, her male friends constantly fretted about being drafted, and sometimes, police vans and teargas would descend on campus, their motivations largely unbeknownst to her. On any given day, her Sproul people-watching might have included a lecture on the value of political speech on college campuses, a demonstration against the Vietnam War, or a march down Telegraph Avenue, which led from campus into the city. UC Berkeley, to her, was a thrilling, semi-utopic reprieve from a culturally homogenous childhood spent in Michigan and the San Fernando Valley; a place where everyone and everything could be reached on foot; a place where she could be an individual; a place where everyone was intellectually serious, but no one took themselves too seriously.

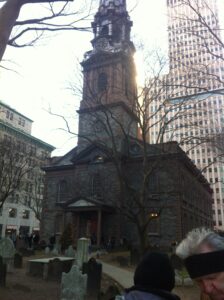

Sproul Plaza during the Free Speech Movement

Linda remained uninvolved in campus politics for her first two years at Cal, but that doesn’t mean she wasn’t paying attention to things happening around her.

“I remember one of the eeriest sights, when I really became aware of what a political hotbed Berkeley was,” she said of witnessing a stand-off outside her freshman dorm, just south of campus, “What turned out to be a SWAT team. They were all cops, just gathering, with shields and helmets and batons. I had never seen anything like that. It was extremely scary. Now if you saw that, you might just shrug and say, ‘Oh, something’s going on.’ But in 1965, it was a real phenomenon.” She didn’t have to be involved in a movement to understand that they were everywhere in Berkeley.

She moved to a new apartment on Ward Street at the beginning of the summer of ‘68—the summer of Robert Kennedy’s assassination, the Poor People’s Campaign, and Nixon’s nomination—and soon found herself spending a lot of time with the Roberts family, whose comings and goings via van and motorcycle she’d observed for weeks before discovering that one of the motorcyclists was her acquaintance, Mark Roberts. The small, green Roberts house was a peculiar one for a college town, and Linda was drawn to the fact that the Roberts family actually acted as a family unit. Linda had many friends, but they were just as independent as she; she didn’t yet have a family in Berkeley.

Zona Roberts and her sons were different. Zona zipped off to class on her motorcycle each morning, and there seemed to be a constant rotation of young people cycling in and out of the house.

“The whole family—they’re a very friendly family. Very, very friendly people. And just very unassuming. At the time, Zona was a student at Berkeley herself. Her husband had died a few years earlier. I don’t know how she did it financially. She was always on the edge, but somehow she managed,” Linda recalled.