Tag: OHC

Announcing Dates for 2021 OHC Educational Programs

The Oral History Center is pleased to announce that applications are now open for the 2021 Introductory Workshop and Advanced Institute!

The Introductory Workshop will held over two days on March 5-6, 2021.

The 2021 Introduction to Oral History Workshop will be held virtually via Zoom over two days on Friday, March 5, from 12–3 p.m. and Saturday, March, 6 from 9 a.m.–1.p.m. Pacific Time. Applications for this workshop are open here and will be accepted through February 16, 2021. Space is limited so apply early to ensure a spot.

will be held virtually via Zoom over two days on Friday, March 5, from 12–3 p.m. and Saturday, March, 6 from 9 a.m.–1.p.m. Pacific Time. Applications for this workshop are open here and will be accepted through February 16, 2021. Space is limited so apply early to ensure a spot.

The two-day day introductory workshop tuition is $200 and is designed for people who are interested in an introduction to the basic practice of oral history. The workshop serves as a companion to our more in-depth Advanced Oral History Summer Institute held in August.

This workshop focuses on the “nuts-and-bolts” of oral history, including methodology and ethics, practice, and recording. It will be taught by our seasoned oral historians and include hands-on practice exercises. Everyone is welcome to attend the workshop. Prior attendees have included community-based historians, teachers, genealogists, public historians, and students in college or graduate school.

The Advanced Institute will be held from August 9-13, 2021.

The OHC is offering an online version of our one-week advanced institute on the methodology, theory, and practice of oral history. This will take place via Zoom from August 9-13, 2021. Applications will be accepted through July 16, 2021. Apply now!

The cost of the Advanced Institute has been adjusted to reflect the online nature of this year’s program. This year’s cost has been adjusted to $550. See below for details about this year’s institute.

The institute is designed for graduate students, postdoctoral fellows, university faculty, independent scholars, and museum and community-based historians who are engaged in oral history work. The goal of the institute is to strengthen the ability of its participants to conduct research-focused interviews and to consider special characteristics of interviews as historical evidence in a rigorous academic environment.

We will devote particular attention to how oral history interviews can broaden and deepen historical interpretation situated within contemporary discussions of history, subjectivity, memory, and memoir.

Overview of the Week

The institute is structured around the life cycle of an interview. Each day will focus on a component of the interview, including foundational aspects of oral history, project conceptualization, the interview itself, analytic and interpretive strategies, and research presentation and dissemination.

Instruction will take place online from 8:30 a.m. – 12:30 p.m. Pacific Time, with breaks woven in. There will be three sessions a day: two seminar sessions and a workshop. Seminars will cover oral history theory, legal and ethical issues, project planning, oral history and the audience, anatomy of an interview, editing, fundraising, and analysis and presentation. During workshops, participants will work throughout the week in small groups, led by faculty, to develop and refine their projects.

Participants will be provided with a resource packet that includes a reader, contact information, and supplemental resources. These resources will be made available electronically prior to the Institute, along with the schedule.

Applications and Cost

The cost of the institute is $550. OHC is a soft money research office of the university, and as such receives precious little state funding. Therefore, it is necessary that this educational initiative be a self-funding program. Unfortunately, we are unable to provide financial assistance to participants. We encourage you to check in with your home institutions about financial assistance; in the past we have found that many programs have budgets to help underwrite some of the costs associated with attendance. We will provide receipts and certificates of completion as required for reimbursement.

Read Amanda Tewes’s recap of the 2020 session here.

Read Q&A with Institute Alums Julia Thomas, Alex Vassar, Alec O’Halloran, Kelly Navies, Meagan Gough, Nicole Ranganath, and Marc Robinson.

Questions?

Please contact Shanna Farrell at sfarrell@library.berkeley.edu with any questions.

Oral History Center Staff’s Top Moments of 2020

The year 2020 has been challenging and tumultuous. However, there have been bright spots as the Oral History Center transitioned to working remotely and conducting interviews over Zoom. We wanted to take a moment to reflect on what has brought us joy and given us strength as we leave 2020 behind.

Amanda Tewes, Interviewer/Historian:

This year has certainly created many challenges for me—as an interviewer and as a person—but I’ve been pleasantly surprised by the resiliency and creativity of my colleagues and the field of oral history as a whole. For example, Roger Eardley-Pryor and I worked with UC Berkeley undergraduate Miranda Jiang from 2019 through summer 2020. Miranda spent months researching and writing an original oral history performance for our 2020 Commencement, only to find that the pandemic had eliminated the potential for an in-person event. After regrouping, Miranda spent part of the summer transforming this performance intended for a live audience to a podcast episode on The Berkeley Remix (“Rice All the Time?”) complete with music and sound effects. This was not her original vision for the oral history performance, but she embraced the new media and its potential for reaching wider audiences, and is now working on an article about the challenges and benefits of this transition. We couldn’t be prouder!

Paul Burnett, Interviewer/Historian:

As a consequence of our adjustments to the COVID-19 pandemic, I realized more than ever that we all need to be better informed about the nature of epidemics and the social patterns that are revealed and exacerbated by them. With the help of our communications manager Jill Schlessinger and UDAR students Nika Esmailizadeh, Esther Khan, Corina Chen and Samantha Ready, we published curriculum content and frameworks for grade 11 students on epidemics in history. This curriculum makes use of our collection of interviews with those who confronted the AIDS epidemic in the early 1980s, along with our podcast on this subject. We are fundraising for a second round of interviews on the globalization of the HIV/AIDS pandemic, as well as a new project to develop curriculum materials on California communities and the environment based on our large collection of oral histories. Our collection is a fantastic resource for teachers, but we will continue to curate our content to make it easier to use in the classroom.

Roger Eardley-Pryor, Interviewer/Historian:

With silver bells ringing this holiday season, we search for silver linings amid the turmoil of 2020. My family’s continued health and safety remains that for which I’m most grateful, and both remain atop of our holiday wish list for you and yours. I’m also grateful and privileged to continue working at UC Berkeley’s Oral History Center (OHC). In the spring of 2018, when I began work at the OHC, my daughter was just 4 months old. This December of 2020, she turns three. Back in March of 2020, with heightened fear of the spreading pandemic and just as the Bay Area’s shelter-in-place orders came down, I corresponded with Dr. Samuel Barondes, a medically trained scientist at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) whose research bridged the fields of psychiatry and molecular neuroscience. Sheepishly, I told Sam my transition to working from home in a tiny one-bedroom apartment, which I shared with my wife and our rambunctious two-year old, would delay my work on his oral history that we recorded the prior year. Sam, now in his eighth decade of vibrant life, remembered well living in a one-bedroom apartment in New York City with his own high-energy two-year-old. Ever the optimist and exuding compassion, Sam told me, “Someday, you’ll treasure these memories of this momentous time…As always, everything is an opportunity!” At that time, I had a hard time hearing Sam’s wisdom. Now, having survived 2020, I understand. Nothing was easy this past year, but, already, I cherish my many months at home working while also watching our young daughter learn and grow. And, despite the past year’s chaos, I’m pleased to have finally published my lengthy oral history interviews with Alexis T. Bell, a professor in the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering in UC Berkeley’s College of Chemistry; with Michael Schilling, a chemist and head of Materials Characterization at the Getty Conservation Institute (GCI) in Los Angeles; and with Aaron Mair, a pioneer of environmental justice and the first Black president of the Sierra Club. In the coming year, I look forward to COVID vaccines, a new US President, and to completing additional oral histories long delayed by the pandemic, including Dr. Sam Barondes’s. I miss the intimacy and comradery of in-person meetings, of handshakes and hugs, of shared stories and raw laughter reverberating in a room, not filtered through a silicon chip. I hope to see you on the other side of this pandemic. From my family to all of yours, we wish you a happy, safe, and healthy holiday season, and may you know peace and justice in the new year.

Jill Schlessinger, Communications Manager/Managing Editor:

There were many highlights this year in the areas of communications, oral history production, and process. It’s wonderful to work with my team of student editors, Ashley Sangyou Kim, JD Mireles, Jordan Harris, Lauren Sheehan-Clark, and Ricky Noel; communications assistant Katherine Chen, and research assistant Deborah Qu, and I want to thank them for their high-quality work and professionalism. The editorial team wrote discursive tables of contents and edited frontmatter and interviews for dozens of oral histories this year, among other projects. We contributed to the Berkeley Women 150 celebrations, including a collection guide to 225 oral histories with UC Berkeley women — alumnae, faculty, staff, administrators, and philanthropists; a Berkeley women oral history web page, and four articles highlighting the achievements of Berkeley women by our undergraduate research assistant Deborah Qu, about alumnae Janet Daijogo and Ida Louise Jackson, faculty Natalie Zemon Davis and Elizabeth Malozemoff, and Berkeley’s first dean of women, Lucy Sprague Mitchell. I launched a new project management tool to track our complex production process, with more than 100 steps, and our many other initiatives, making collaboration and tracking easier. The Smithsonian Magazine, KPIX-CBS, NPR, East Bay Yesterday podcast, the San Francisco Chronicle, and the movie, Crip Camp, winner of the Audience Prize for documentary at the Sundance Film Festival, among others, featured our oral histories or interviews with our historians/interviewers. A personal highlight for me was writing the article “Never Forget? UC Berkeley’s Oral History Center documents memories of the Holocaust for researchers and the public,” in observance of the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz.

Todd Holmes, Interview/Historian:

One of my fondest memories this year at the OHC was our Advanced Summer Institute. Each year we host over 50 participants during this week-long event, teaching the ins and outs of oral history and helping the wide-range of attendees in developing their individual projects. Like so many activities on the Berkeley campus, however, Covid-19 forced us to come up with a safer alternative. Thanks to Shanna Farrell—the office’s longtime Advanced Summer Institute coordinator—we held the institute via Zoom with minimal bumps along the road, allowing us to connect with participants from around the world. Indeed, it was not uncommon to have participants from 3 or 4 different time zones in one meeting. It was an amazing experience, one that highlighted our interconnectedness, as well as what can be achieved with technology and teamwork.

Shanna Farrell, Interview/Historian:

This year has been a doozy. When the shelter-in-place order hit in March, we had to re-learn how to structure our days and focus on work while the world crumbled around us. Many of our projects paused while we collectively tried to regroup and design a path forward. To call this difficult, especially while constantly refreshing my newsfeed, is an understatement. So, I turned to one of my great loves: audio. We launched a series of special episodes of our podcast, The Berkeley Remix, called “Coronavirus Relief.” The intention was to bring stories from the field of oral history, things that had been on our mind, lessons from the past, and interviews that helped us get through, to find small moments of happiness. I served as the producer and editor of these episodes, even writing my own episodes, and worked with Amanda Tewes and Roger Eardley-Pryor, proving that remote collaboration was still possible. Making these seven episodes of The Berkeley Remix was one of my favorite parts of 2020, as it allowed me stay connected to my colleagues, gave me space to think about the value of oral history, and engage our audience during dark days.

Martin Meeker, Director:

Before joining the Oral History Center in 2003 as a postdoc, I had already read the Center’s interview with Willie Brown about his years as Speaker of the California Assembly. I held this up as the pinnacle of political oral history and resolved that one day I would conduct a follow-up and ask him about his two terms as San Francisco Mayor. In 2015 and 2016 the opportunity arose and I conducted a 10 hour oral history with Mayor Brown and I was thrilled with the results. And, finally, in 2020 the mayor gave his blessing for us to release this second volume of what is now a thorough and fascinating life history.

The Oral History Center Plans to Launch New Project on Contact Tracing

The COVID-19 crisis has ushered in a new era of world history, and continues to have a profound impact on daily life around the world, including the Bay Area. But the fight against this global pandemic also includes a regional public health tool: contact tracing. News outlets and public health officials often say that manual contact tracing is key to protecting the community.

The Oral History Center hopes to launch a project about contact tracing that will document the historic nature of the work, as well as evaluate its effectiveness in this moment as it relates to public health, community, and politics.

Interested in helping to make this project a reality? We are now accepting tax-deductible donations!

Contact tracing, the process of charting the chain of infection to control transmission, has been practiced since the 1930s. It first played a key role in reducing the spread of syphilis among U.S. troops during World War II. Later, public health advisers, referred to as P.H.A.s, used this strategy to control tuberculosis, smallpox, and the 2009 H1N1 Pandemic. Early P.H.A.s were required to have a college degree, preferably in liberal arts, with a variety of work experience that gave them enough emotional intelligence to form connections with anyone from business executives to rural farmers. P.H.A.s have been incredibly successful in reducing the spread of disease and infection, and were responsible for blowing the whistle on the Tuskegee experiment.

The process has shifted since then, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, and experts often cite contact tracing as the key to mitigating the spread of the coronavirus. Job requirements are different, and in San Francisco, furloughed city employees––like librarians, city attorneys, and tax assessors––are filling these roles previously held exclusively by P.H.A.s.

As the COVID-19 crisis continues to reshape all facets of life, it is essential to explore the experiences of public health experts and contact tracers in real time. The OHC hopes to record and archive oral history interviews with contact tracers and others who are fighting COVID-19 by planning health policy, analyzing data, and tracking the human toll of the outbreak. In-depth topical interviews about tracking the spread of the virus will document the current moment and the intensive human work of manual contact tracing.

Help us make this project a reality by making a tax-deductible donation here.

*Note: Please check “This Gift is in the Honor or Memory of Someone” when you make your donation. Please write “Contact” for the first name, and “Tracing” for the last name fields.

Thank you for supporting our work!

Interested in learning more? Contact Shanna Farrell (sfarrell@library.berkeley.edu) or Amanda Tewes (atewes@berkeley.edu).

OHC at the Oral History Association Conference

As with most things this year, the 2020 Oral History Association conference will be held digitally. The theme, “The Quest for Democracy: One Hundred Years of Struggle,” was inspired by the Centennial of the 19th Amendment, which granted women the right to vote, yet excluded Black men and women in the Jim Crow South. In choosing this theme, we hoped to encourage submissions that interrogate the idea of “Democracy,” its inherent assumptions and challenges; submissions of oral history projects that illuminate the ways in which we participate in democracy, who has access to the political process and who has historically struggled to gain such access.

OHC’s own Shanna Farrell and the Smithsonian’s Kelly Navies (who is one of our Advanced Summer Institute alumni!) served as the conference co-chairs and are very excited to kick off what promises to be an engaging and dynamic week of presentations.

If you’re attending next week, we’d love for you to check out sessions from the OHC staff. Here’s the lineup:

- Monday, October 19:

- Amanda Tewes leading “An Oral Historian’s Guide to Public History” workshop from 11am – 2:30pm ET/8 – 11:30am PT

- Wednesday, October 21:

- Paul Burnett will be on the “Educating in High School and University Involves Listening” panel talking about UC Berkeley OHC K16 Outreach Project: The HIV/AIDS Curriculum Pilot at 3:30pm ET/12:30 PT

- Shanna Farrell will be chairing the “Oral History for an Audience: Podcasts, Performance, and Documentaries” session at 3:30pm ET/12:30 PT

- Thursday, October 22:

- Roger Eardley-Pryor will be talking to OHC narrator Aaron Mair for the “Hitched to Everything: Aaron Mair, Environmental Justice, and the Sierra Club” session that will be chaired by Shanna Farrell at 3:30pm ET/12:30 PT

We hope to “see” you there!

The Value of Open Space

The Bay Area is beautiful. Its myriad of picturesque beaches, mountains, woods, and lakes is a big part of why it’s such a desirable place to live. And since March, when the California shelter-in-place order was issued to slow the spread of the coronavirus pandemic, the value of these outdoor spaces has never been more clear.

The East Bay Regional Park District has worked to preserve open space since its founding in 1934. Over the years, it has acquired 125,000 acres of land, which spans 73 parks. The public access to nature that the concert of parks provide adds to quality of life here, especially with the parks’ proximity to urban areas (which is detailed in Season 5 of The Berkeley Remix podcast, Hidden Heroes).

There are many people in the district’s network, both those who make up the workforce and those who help it thrive in other ways, like documenting its history, selling their land to them, and advocating for its mission. Since 2017, I’ve had the pleasure of leading the East Bay Regional Park District Parkland Oral History Project, for which I have the opportunity to record the stories of the people who make the district special.

This past year, I interviewed ranchers, activists, a maintenance worker, an artist, the daughter of a historian, and a park planner, all of whom had unique perspectives to share about the legacy of the district. Here are the ways in which each of their stories speak to the value of preserving open space:

Diane Lando grew up in the East Bay on a ranch. She became a writer, drawing inspiration from her childhood. As the Brentwood Poet Laureate, she published The Brentwood Chronicles, which consists of two books. These books express just how important growing up on the ranch had been for her, giving her a sense of independence and self.

Raili Glenn immigrated to the United States from Finland and settled in California as a newly married woman. She had a successful career in real estate and she and her late husband bought a house in Las Trampas, which is now owned by the EBRPD. This house meant a great deal to her —it’s beauty, quiet, and charm helped her find home in the parks.

Roy Peach grew up in the East Bay, spending much of his childhood in Sibley Quarry, which is now owned by the park. Growing up here, he learned about the environment, geology, and himself as he spent as much time as he could outdoors. His love of nature has followed him into adulthood, and camping has continued to be an important pastime.

Ron Batteate is a fourth generation rancher. He grew up in the East Bay, following in the footsteps of the men who came before him. He leases land from the district where he grazes his cattle. His love for open space and his livestock runs deep, evident in the way he talks about the importance of understanding nature with commitment and passion. If I were a cow, I’d want to be in Ron’s herd.

Janet Wright grew up in Kensington with parents who were very involved with their community. Her father, Louis Stein, was a pharmacist by day and a local historian by night. He collected artifacts from around town, which proved to be important in the documentation of local history. The maps, photos, letters, newspapers, ephemera — and horse carriage — that he collected are now archived at both the History Center in Pleasant Hill and with the Contra Costa Historical Society. These materials help tell the story of the importance of the district in many people’s lives.

Glenn Adams is the nephew of Wesley Adams, the district’s first field employee. Wesley was hired in 1937 and had a long career with the district, retiring after decades of service. Glenn fondly remembers his uncle Wes, who he says shaped his life greatly, including passing along his passion for the parks. Glenn has in turn shared his love of the outdoors with his family, who continue to use the parks today.

Mary Lenztner grew up on a ranch in Deer Valley that her parents, who both immigrated from the Azores, bought in 1935. She moved to San Jose with her mother after her father’s death, but returned to the area later as an adult. As her children got older, she became curious about her family’s ranching legacy. She learned about raising cattle, and went on to take over her family’s ranch. She lived there, raising cattle and other livestock, for 25 years before selling it to the district. Her relationship with this land helped her connect with her family and their past, and her interview drives home the importance of place in our lives.

Bev Marshall and Kathy Gleason live in Concord near the Naval Weapon Stations, part of which is now owned by the district . When they were deactivating the base, they both fought to keep it open space. Their work helped them form a lifelong friendship, find community, and a voice in local politics, while successfully limiting development in the area.

Rev. Diana McDaniel is a reverend in Oakland and is the President of Board for the Friends of Port Chicago. She has long been active in educating the public about the Port Chicago tragedy, which her uncle was involved in. She works with the district (and National Park Service) to make sure the story of what happened at Port Chicago isn’t forgotten. Her story illustrates how important parks are not just for open space, but for public history, too.

John Lytle was a maintenance worker at the Concord Naval Weapons Station where he specialized in technology. He found fulfillment in his work there over the years, and his interview demonstrates the careful planning that goes into transitioning a naval base into a public park.

Brian Holt is a longtime EBPRD employee who currently serves as a Chief Planner. He has been involved in many of the district’s initiatives, including acquiring much of its land. He works with community members, trying to understand issues from different perspectives. He cultivates understanding of the nuances of each issue, ultimately informing the district’s involvement in preserving open space.

All of these narrators demonstrate just how important the district is to preserving public space, especially space that is accessible to everyone. Each person illustrates the power the parks and the communities that spring up within them, which is more important than ever during these tumultuous times.

This year, I interviewed:

Diane Lando

Raili Glenn

Glenn Adams

Roy Peach

Mary Lentzner

Beverly Marshall

Kathy Gleason

Janet Wright

Ron Batteate

John Lytle

Brian Holt

Reverend Diana McDaniel

And

Melvin Edwards

Peter Bradley

Both for the GRI African American Artist Initiative, outlined in Amanda Tewes’ blog post

You’re Invited to the Summer Edition of the OHC Book Club

Oral History, Literature, and the June OHC Book Club Selection

When the shelter-in-place order was issued in mid-March by California Governor Gavin Newsom, many thoughts ran through my head. One of the milder ones — the kind that comes from the part of me that tries to find a silver lining in bad situations — was that I might have more time to read. I’ve always been an avid reader, mostly of fiction and narrative non-fiction, and often find myself counting down the hours until I can return to my book.

But in those early days of the global COVID-19 pandemic, I couldn’t concentrate on many things other than the news. My working hours bled into my free time as I tried my best to knock projects off my to-do list and remain productive as the world crumbled around us.

And then one day I found myself staring at my bookshelf, the myriad of colorful spines calling to me. A soft pink cover caught my eye. I pulled Severance, a post-apocalyptic book by Ling Ma, off the shelf and cracked it open. The novel follows Candace Chen as a flu pandemic hits modern-day New York City. As a native New Yorker, It hit close to home, and was strangely cathartic. (It didn’t hurt that the book is beautifully written and Ma’s prose was absorbing.) It allowed me to escape in a way that was right for the limits of my focus at the time.

Next I read Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel, another post-apocalyptic novel about a global flu pandemic. This one split the timeline between when the pandemic hit Toronto, Canada, and twenty years in the future. In it, the author uses oral history as a device to connect the timelines. Every time I encounter the term “oral history” in literature – be it fiction or non-fiction – my heart quickens, never knowing if it’s being misused.

As I read the fictional oral history interview transcript interspersed throughout the second half of Station Eleven, I was delighted, and deeply impressed, that Mandel seemed to understand that oral history is a type of long-form, recorded interview. This deepened my appreciation for both the writer and the book, discovering that there are people out there who don’t blur the lines between a clearly-defined methodology (about which I’ve mused on this very blog), taking the time to do their due diligence before employing a term they’ve heard about in passing.

Ever since I read World War Z: An Oral History of the Zombie Apocalypse by Max Brooks, I’ve loved when authors use fictional oral history interviews to tell a story. I find the interviewer and narrator exchange, the chorus of voices, and the details from the past an engaging way to draw the reader in. Many times, I feel like I’m in the room with them.

My colleague, Amanda Tewes agrees. “I like that the familiarity of oral history draws me into a story (almost as if it was real) and allows the author to toy with memory in a way that is difficult when juggling many characters,” she says.

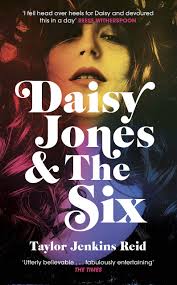

This brings us to our next OHC Oral History Book Club selection, picked by Tewes, which embraces the trend of oral history as a literary device in fiction. We’ll be reading Daisy Jones & the Six, by Taylor Jenkins Reid, which the New York Times calls “a gripping novel about the whirlwind rise of an iconic 1970s rock group and their beautiful lead singer, revealing the mystery behind their infamous breakup.”

The story unfolds through a series of fictional oral histories. The format is the kind we often find on the pages of Entertainment Weekly or Vanity Fair, inspired by the hallmark oral history book Edie about Edie Sedgewick. The book is a best-seller, a Reese Witherspoon Book Club pick, and is the basis for a new mini-series from Witherspoon’s production company.

We’re inviting you to join us for the June installment of our book club. On June 15, we’ll be holding a virtual meeting. We’ll be discussing the book, the use of oral history in literature and pop culture, and more.

RSVP to sfarrell@library.berkeley.edu if you’d like to join us for our book club via Zoom on Monday, June 15 at 11am PST/2pm EST.

Until then, happy reading and stay safe!

Episode 4 of the Oral History Center’s Special Season of the “Berkeley Remix” Podcast

Lately, things have been challenging and uncertain. We’re enduring an order to shelter-in-place, trying to read the news, but not too much, and prioritize self-care. Like many of you, we here at the Oral History Center are in need of some relief.

So, we’d like to provide you with some. Episodes in this series, which we’re calling “Coronavirus Relief,” may sound different from those we’ve produced in the past, that tell narrative stories drawing from our collection of oral histories. But like many of you, we, too, are in need of a break.

The Berkeley Remix, a podcast from the Oral History Center of the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley. Founded in 1954, the Center records and preserves the history of California, the nation, and our interconnected world.

We’ll be adding some new episodes in this Coronavirus Relief series with stories from the field, things that have been on our mind, interviews that have been helping us get through, and finding small moments of happiness.

Our fourth episode is from Roger Eardley-Pryor.

This is Roger Eardley-Pryor. I’m am an interviewer and historian of science, technology, and the environment at Berkeley’s Oral History Center. For this episode of Coronavirus Relief, I want to share stories with you about the very first Earth Day in 1970, which just celebrated its 50th anniversary.

Mercy, mercy me! Earth Day turned 50 in April 2020. A half-century ago, on April 22, 1970, environmental awareness and concern exploded in a nationwide outpouring of celebrations and protests during the world’s first Earth Day. That first Earth Day drew an estimated twenty million participants across the United States—roughly a tenth of the national population—with involvement from over ten thousand schools and two thousand colleges and universities. That first Earth Day, on April 22, became the then-largest single-day public protest in U.S. history. The actual numbers of participants were even higher. Several universities, notably the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, organized massive Earth Day teach-ins, some of which they held in the weeks before April 22nd to avoid overlapping with their final exams. From New York City to San Francisco, from Cincinnati to Santa Barbara, from Birmingham to Ann Arbor—millions of Americans gathered on campuses, met in classrooms, visited parks and public lands together, participated in local clean-ups, and marched in the streets for greater environmental awareness and to demand greater environmental protections. Even Wisconsin Senator Gaylord Nelson was surprised. And it was Senator Nelson who, in the fall of 1969, first promoted the idea for nation-wide teach-ins about the environment. He called Earth Day in 1970 a “truly astonishing grass-roots explosion.” In the fifty-years since, Earth Day events have spread globally to nearly 200 nations, making it the world’s largest secular holiday celebrated by more than a billion people each year.

But this past April, despite years of planning for Earth Day’s fiftieth anniversary, the novel coronavirus—itself a world-wide environmental event—disrupted Earth Day 2020 plans across the planet. We were not able to celebrate Earth Day’s golden anniversary as previously planned. Instead, we can commemorate it with recollections—and lessons learned—by those who attended and organized the first Earth Day events in 1970. The Oral History Center’s archives list over seventy interviews that mention Earth Day.

I’ve selected here a few memories of the first Earth Day from our Sierra Club Oral History Project, a collaboration between the Sierra Club and Berkeley’s Oral History Center, that was initiated soon after that first Earth Day. These Earth Day memories from Sierra Club members begin with experiences in the streets of New York City, they include memories at the forefront of environmental law, and they conclude with a Sierra Club member who was inspired to activism at the University of Michigan’s first-ever Earth Day teach-in.

We’ll begin with Michele Perrault, who in the 1980s and 1990s was twice elected as president of the Sierra Club. Back in 1970, Michele Perrault lived and worked in New York City as an elementary-school science teacher. New York City was the site the nation’s largest celebrations of Earth Day, which captured nationwide media attention given that NBC, CBS, ABC, The New York Times, Newsweek, and Time Magazine were all headquartered in Manhattan. Perrault, who was then twenty-eight years old, taught in the demonstration school at the Bank Street College of Education. Bank Street College was founded more than 50 years earlier, in 1916, by a women named Lucy Sprague Mitchell, a child education reformer and, before that, Berkeley’s first Dean of Women. The Oral History Center has a great interview with her, too. But back to Michele Perrault.

For her part, Perrault told me—during her oral history—how she organized “a Bank Street program out in the street for Earth Day in New York City.” … “we had our own booth, and I had the kids there … Mostly we sang songs and danced around and had some visuals and books that people could read or get, and we had some pamphlets from the [Bank Street] College that talked about it.” In the process, Perrault and her students joined hundreds of thousands of other Earth Day participants in the streets of Manhattan. John Lindsay, the Republican mayor of New York, had closed traffic on Fifth Avenue for Earth Day, and he made Central Park available for gigantic crowds to march and celebrate together. The New York Times estimated over 100,000 people visited New York’s Union Square throughout Earth Day.

Earlier in 1970, Michele Perrault joined student teachers to plan Earth Day teach-ins in New York. That’s when Perrault met René Dubos—a famous microbiologist, an optimistic environmentalist, and a Pulitzer-Prize-winning author who first coined the phrase “Think Globally, Act Locally.” At that time, Michele Perrault served as education chair for the Sierra Club’s Atlantic Chapter in New York, for whom she had recently started a newsletter called Right Now!—a monthly publication full of ideas for environmental educators. Two copies of Right Now! are included in the appendix to Michele Perrault’s printed oral history, which is available online, like all of the Oral History Center’s interviews. In one edition of Right Now!, Perrault recalled René Dubos’s advice for the upcoming first Earth Day.

Dubos “stressed the importance and need for people to take time to reevaluate what is needed for quality of life, to sift and sort alternatives—perhaps not in existence now, to look in a new way at what the future could be like, and then devise plans for making it so.” Perrault added this: “We, as teachers, need to ask new questions about our own values, about our own social and economic systems and their relationship to the environment, so as to enrich the present and potential environment for children.”

In 1971, less than a year after Earth Day, Perrault organized at Bank Street College an education conference titled “Environment and Children.” She invited René Dubos as the keynote speaker, and she remembered: Dubos called for stimulating environments for children that offered “the ability to choose, to have variety, to not just be in one place where everything was static around them and where they weren’t in control. [He] had a big paper on this whole issue of free will and being able to make choices, and how the environment would influence them.” Years later, after moving to California, Perrault took her own children on annual backpacking trips deep into the High Sierra Nevada mountains where they could run wild and free, stimulated by natural wilderness.

Michele Perrault was recruited to the Sierra Club shortly before Earth Day by a guy named David Sive, a pioneer of environmental law in New York, whose children Perrault taught in her science classroom. The Sierra Club Oral History Project includes a great interview with David Sive from 1982. Another Sierra Club member and trailblazer of environmental law is James Moorman, Moorman shared his own memories of the first Earth Day during his oral history in 1984. Back in 1970, Moorman had then recently joined the newly created Center for Law and Social Policy, or CLASP. CLASP is an influential public-interest law firm in Washington, DC. In the late 1960s, Jim Moorman was a young trial lawyer who brought two cases that became landmarks in environmental law. The first was a petition to the US Department of Agriculture to de-register the pesticide DDT. The second was a suit against the US Department of the Interior challenging construction of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline. For the pipeline case, Moorman pioneered use of the National Environmental Policy Act (or NEPA), which had just been enacted in January 1970. Based on NEPA, Moorman demanded from the Interior Department a detailed Environmental Impact Statement for the pipeline project.

Moorman recalled: “the preliminary injunction hearing for the Trans-Alaska Pipeline was originally set for Earth Day. … when the judge first set the hearing, I said, ‘Holy cow! He set the hearing for this on Earth Day and he doesn’t know it, and the oil companies don’t know it. I’m going to get to make my argument on Earth Day. That’s fantastic!’ But then there was a postponement, and the argument didn’t occur until two weeks later. But it was wonderful anyway.” Jim Moorman won his case. But Congress directly intervened to approve the pipeline by law. Nonetheless, Moorman’s injunction forced the oil companies to spend more than three years and a small fortune on engineering, analysis, and documentation for the project. The final Environmental Impact Statement for the Trans-Alaska Pipeline stretched to nine volumes! Moorman’s legal intervention helped produce a safer pipeline that, today, is still considered a wonder of engineering.

In the year following the first Earth Day, Moorman accepted a new job as the founding Executive Director of the Sierra Club Legal Defense Fund, now known as Earthjustice. It was one of the nation’s earliest and remains one of the most influential public-interest environmental law organizations. Moorman directed the Sierra Club Legal Defense Fund through 1974, and he worked as a staff attorney with the organization through 1977. That was when he became Assistant Attorney General for Land and Natural Resources under President Jimmy Carter. But in his 1984 oral history, Jim Moorman reflected on the importance of the first Earth Day for environmental law: “The fact is Earth Day came rather early in all this [environmental law] movement. We’ve been living on the energy created by Earth Day ever since.” Mike McCloskey—also a lawyer—couldn’t agree more.

Back in 1970, Mike McCloskey was still getting used to his new his role as Executive Director of the Sierra Club, a position McCloskey took up in the wake of David Brower and held through 1985. In the first of Mike McCloskey’s two oral histories—that first one from 1981—McCloskey recalled the Earth-Day-era as “a very exciting time in terms of developing new theories [of environmental law]. Our spirits were charged up. The courts were anxious to make law in the field of the environment. There were judges who were reading, and they were stimulated by the prospect. They were eager to get environmental cases.”… “what became clear over the next few years [after Earth Day] were that dozens of, if not hundreds, of laws were passed and agencies brought into existence.” He’s right. A few months after the first Earth Day, President Nixon established the Environmental Protection Agency. Over the next few years, Congress passed a suite of landmark environmental statutes—including an amended Clean Air Act; the Clean Water Act; the Safe Drinking Water Act; the Endangered Species Act; the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act; the Toxic Substances and Control Act and many others … all of which—thus far—have avoided extinction.

Mike McCloskey remembered the first Earth Day in 1970 as an explosion of the environmental consciousness that had grown steadily throughout the late 1960s. In 1968, not long before Earth Day, conservationists like McCloskey thought the best of times had already happened. The creation of Redwood National Park in California, North Cascades National Park in Washington state, and the passage of both the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act and the National Trails System Act, all occurred in that revolutionary year of 1968. McCloskey recalled, “We, at that moment, thought this was some high point in conservation history and wondered whether much would happen thereafter.” In January 1969, President Richard Nixon came into office. McCloskey and other Sierra Club leaders remembered: we felt “very defensive and threatened, not realizing that we were on a threshold of an explosion into a period of our greatest growth and influence.” By 1970, instead of a plateau or even a decline in environmental efforts, Sierra Club leaders saw the American environmental movement experience what McCloskey described as “a tremendous take-off in terms of the overall quantity of activity, enthusiasm, and support with Earth Day. … it was just an eruption of activity on every front.”

But much to his surprise, with Earth Day in 1970, McCloskey also saw how many traditional leaders of the conservation movement were quickly regarded as “old hat and out of step with the times.” In their place, he witnessed how people “emerged at the student level, literally from nowhere, who were inventing new standards for what was right and what should be done and whole new theories overnight. For instance, I remember hostesses who were suddenly saying, ‘I can’t serve paper napkins anymore. I’ve got to have cloth napkins.’ Someone had written that paper napkins were terribly wrong—and colored toilet paper was regarded as a sin. But all sorts of people from different backgrounds coalesced in the environmental movement. People who were interested in public health suddenly emerged and very strongly.” One such person was Doris Cellarius.

In 1970, Doris Cellarius lived in Ann Arbor, Michigan, with her children and husband, Dick Cellarius, a professor of botany who was then teaching at the University of Michigan. According to Doris, she and Dick were both members of the Sierra Club in 1970, but mostly for hiking and social engagement, less for activism. The extraordinary events surrounding Earth Day in Ann Arbor changed everything. As Doris explained: “Earth Day came as a great shock to me because it had never occurred to me that the environment didn’t clean itself. I thought that water that flows along in a creek was purified by sunlight, and I guess I didn’t know a lot about where pollution came from. When I learned at the time of Earth Day how much pollution there was and how bad pesticides were, I instantly became very active in the pollution area of the environment.”

In the wake of Earth Day, Doris Cellarius drew upon her master’s degree in biology from Columbia University to become a leading grassroots activist and environmental organizer, especially against the use of pesticides and other toxic chemicals. Within the Sierra Club, she became head of several local and national committees that focused on empowering people in campaigns for hazardous waste clean-up and solid waste management. In her oral history interview from 2002, Doris Cellarius reflected on the impetus behind her decades of environmental activism: “I learned at Earth Day there was pollution. So, I think, having learned there was pollution, I decided that people should find out ways to stop creating that pollution.” Doris Cellarius wasn’t the only person whose life was changed by the events of Earth Day in Ann Arbor.

As a graduate student in forestry, a young Sierra Club member named Doug Scott co-organized the nation’s very first Earth Day teach-in at the University of Michigan. Their teach-in included the cast from the musical Hair, the governor of Michigan, several US Senators, as well as a public trial of the American car, which the students convicted of murder and sentenced to death by sledgehammer! I strongly encourage you to read the Sierra Club oral history of Doug Scott, who not only witnessed these events, but helped make them happen.

Fifty years ago, in 1970, the dynamic events surrounding the first Earth Day reflected how environmental issues could rapidly mobilize new publics for radical reform and institutional action. Indeed, the small organization created to nationally coordinate the first Earth Day took the name Environmental Action. Denis Hayes, the then-twenty-five-year-old national coordinator for Environmental Action, announced on Earth Day, “We are building a movement … a movement that values people more than technology, people more than political boundaries and political ideologies, people more than profit.” This exuberance for a new kind of environmental movement, according to historian John McNeill, arose “in a context of countercultural critique of any and all established orthodoxies.” But, at its root, Earth Day—and the flowering of concern for Spaceship Earth and all travelers on it—constituted “a complaint against economic orthodoxy.” According to John McNeil, “It was a critique of the faith of economists and engineers, and their programs to improve life on earth.” For new adherents to this ecological insight, the popularity of Earth Day’s events contributed collectively to “a general sense that things were out of whack and business as usual was responsible.” That all sounds terribly familiar today.

This year, on the golden anniversary of Earth Day, life all across the planet is out of whack and business as usual has come to a sudden stop. From climate change to the novel coronavirus to the deteriorating condition of American politics, a slew of increasingly complex and interconnected problems affect us all. But perhaps, this moment—like the one in 1970—offers a unique opportunity to think how we might begin things anew. Perhaps, as René Dubos advised on the first Earth Day in April 1970, we in 2020 can “take time to reevaluate what is needed for quality of life, to sift and sort alternatives … to look in a new way at what the future could be like, and then devise plans for making it so.” May it be so. May you help make it so.

Episode 3 of the Oral History Center’s Special Season of the “Berkeley Remix” Podcast

Lately, things have been challenging and uncertain. We’re enduring an order to shelter-in-place, trying to read the news, but not too much, and prioritize self-care. Like many of you, we here at the Oral History Center are in need of some relief.

So, we’d like to provide you with some. Episodes in this series, which we’re calling “Coronavirus Relief,” may sound different from those we’ve produced in the past, that tell narrative stories drawing from our collection of oral histories. But like many of you, we, too, are in need of a break.

The Berkeley Remix, a podcast from the Oral History Center of the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley. Founded in 1954, the Center records and preserves the history of California, the nation, and our interconnected world.

We’ll be adding some new episodes in this Coronavirus Relief series with stories from the field, things that have been on our mind, interviews that have been helping us get through, and finding small moments of happiness.

Our third episode is from Amanda Tewes.

Greetings, everyone. This is Amanda Tewes.

As we are all still hunkering down at home, I wanted to share with you a few selections from Robert Putnam’s classic book, Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. Now, I can’t say that this book is a personal favorite of mine – in fact, it brings up some not-so-fun memories of cramming for my doctoral exams in American history – but it has been on my mind lately, especially in thinking about our shifting social obligations to one another in times of crisis, like the 1918 Influenza Epidemic or the heady days after 9/11.

Putnam published Bowling Alone in 2000, following decades of what he saw as degenerating American social connections, and much of the book reads like a lament of a changing American character.

In the context of our current moment, the following passages stood out to me:

……………………………………………………………………………………………………….

The Charity League of Dallas had met every Friday morning for fifty-seven years to sew, knit, and visit, but on April 30, 1999, they held their last meeting; the average age of the group had risen to eighty, the last new member had joined two years earlier, and president Pat Dilbeck said ruefully, “I feel like this is a sinking ship.” Precisely three days later and 1,200 miles to the northeast, the Vassar alumnae of Washington, D.C., closed down their fifty-first – and last – annual book sale. Even though they aimed to sell more than one hundred thousand books to benefit college scholarship in the 1999 event, co-chair Alix Myerson explained, the volunteers who ran the program “are in their sixties, seventies, and eighties. They’re dying, and they’re not replaceable.” Meanwhile, as Tewksbury Memorial High School (TMHS), just north of Boston, opened in the fall of 1999, forty brand-new royal blue uniforms newly purchased for the marching band remained in storage, since only four students signed up to play. Roger Whittlesey, TMHS band director, recalled that twenty years earlier the band numbered more than eighty, but participation had waned ever since. Somehow in the last several decades of the twentieth century all these community groups and tens of thousands like them across America began to fade.

It wasn’t so much that old members dropped out – at least not any more rapidly than age and the accidents of life had always meant. But community organizations were no longer continuously revitalized, as they had been in the past, by freshets of new members. Organizational leaders were flummoxed. For years they assumed that their problem must have local roots or at least that it was peculiar to their organization, so they commissioned dozens of studies to recommend reforms. The slowdown was puzzling because for as long as anyone could remember, membership rolls and activity lists had lengthened steadily.

In the 1960s, in fact, community groups across America had seemed to stand on the threshold of a new era of expanded involvement. Except for the civic drought induced by the Great Depression, their activity had shot up year after year, cultivated by assiduous civic gardeners and watered by increasing affluence and education. Each annual report registered rising membership. Churches and synagogues were packed, as more Americans worshipped together than only a few decades earlier, perhaps more than ever in American history.

Moreover, Americans seemed to have time on their hands. A 1958 study under the auspices of the newly inaugurated Center for the Study of Leisure at the University of Chicago fretted that “the most dangerous threat hanging over American society is the threat of leisure,” a startling claim in the decade in which the Soviets got the bomb. Life magazine echoed the warning about the new challenge of free time: “Americans now face a glut of leisure,” ran a headline in February 1964. “The task ahead: how to take life easy.” …

…For the first two-thirds of the twentieth century a powerful tide bore Americans into ever deeper engagement in the life of their communities, but a few decades ago – silently, without warning – that tide reversed and we were overtaken by a treacherous rip current. Without at first noticing, we have been pulled apart from one another and from our communities over the last third of the century.

Before October 29, 1997, John Lambert and Andy Boschma knew each other only through their local bowling league at the Ypsi-Arbor Lanes in Ypsilanti, Michigan. Lambert, a sixty-four-year-old retired employee of the University of Michigan hospital, had been on a kidney transplant waiting list for three years when Boschma, a thirty-three-year-old accountant, learned casually of Lambert’s need and unexpectedly approached him to offer to donate one of his own kidneys.

“Andy saw something in me that others didn’t,” said Lambert. “When we were in the hospital Andy said to me, ‘John, I really like you and have a lot of respect for you. I wouldn’t hesitate to do this all over again.’ I got choked up.” Boschma returned the feeling: “I obviously feel a kinship [with Lambert]. I cared about him before, but now I’m really rooting for him.” This moving story speaks for itself, but the photograph that accompanied this report in the Ann Arbor News reveals that in addition to their differences in profession and generation, Boschma is white and Lambert is African American. That they bowled together made all the difference. In small ways like this – and in larger ways, too – we Americans need to reconnect with one another. That is the simple argument of this book.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………….

There is a lot to find discouraging these days, but I actually have been heartened to see the ways in which Americans – and individuals the world over – have been committing and recommitting to each other and to their communities. Citing a “now more than ever” argument, folks are setting up local pop-up pantries with food, household supplies, and books; some are reaching out to their neighbors for the first time; and of course, we are practicing social distancing not just to keep ourselves safe, but also our communities.

Witnessing these acts, I have to wonder if Putnam’s argument about a decline in social obligations and connectivity was just one moment in American history and not a full picture. What will the historical narrative about this time be? Are we now experiencing a blip in social relations, or is this a great turning point? I’m hoping for the latter.

Stay safe, everyone. Until next time!

Episode 2 of the Oral History Center’s Special Season of the “Berkeley Remix” Podcast

Lately, things have been challenging and uncertain. We’re enduring an order to shelter-in-place, trying to read the news, but not too much, and prioritize self-care. Like many of you, we here at the Oral History Center are in need of some relief.

So, we’d like to provide you with some. Episodes in this series, which we’re calling “Coronavirus Relief,” may sound different from those we’ve produced in the past, that tell narrative stories drawing from our collection of oral histories. But like many of you, we, too, are in need of a break.

The Berkeley Remix, a podcast from the Oral History Center of the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley. Founded in 1954, the Center records and preserves the history of California, the nation, and our interconnected world.

We’ll be adding some new episodes in this Coronavirus Relief series with stories from the field, things that have been on our mind, interviews that have been helping us get through, and finding small moments of happiness.

Our second episode is from Shanna Farrell.

These are strange, challenging times that we’re living through. As we shelter in place near and far, trying to reduce our chances of contracting the coronavirus, each day brings news of something else, the dust barely settled from the day before. It’s forced us to adapt quicker than we thought possible. Or maybe that’s just me.

As the fallout from this global pandemic unfolds, I’ve been watching as an industry I love – food and beverage – has begun to collapse. Bars and restaurants all over the world, including in the Bay Area, have closed their doors indefinitely. There are over half a million restaurant workers in San Francisco alone, many of whom are scrambling to stay on their feet. My partner, who manages a bar in the heart of a thriving neighborhood, was temporarily laid off, along with over 1,000 other employees in his company alone. But as their income and health insurance evaporated, people in the service industry have banded together, creating fundraisers and support groups. Maybe there is hope in the dark.

This community-driven spirit is one of the reasons why I cherish the food and beverage industry. It’s also made me think about Rebecca Solnit’s 2009 book, Paradise Built in Hell: The Extraordinary Communities That Arise in Disaster. Solnit chronicles how people pull together in times of crisis from the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake to 9/11. As a realist who tries my best to be optimistic, I’m hoping that we can all take a page out of this book – restaurant industry and beyond – and emerge from this pandemic stronger than when it found us.

Here’s an excerpt from the beginning of Paradise Built in Hell, a chapter called “The Mizpah Cafe” about the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake.

The Mizpah Cafe

The Gathering Place

The outlines of this particular disaster are familiar. At 5:12 in the morning on April 18, 1906, about a minute of seismic shaking tore up San Francisco, toppling buildings, particularly those on landfill and swampy ground, cracking and shifting others, collapsing chimneys, breaking water mains and gas lines, twisting streetcar tracks, even tipping headstones in the cemeteries. It was a major earthquake, centered right off the coast of peninsular city, and the damage it did was considerable. Afterward came the fires, both those caused by broken gas mains and chimneys and those caused and augmented by the misguided policy of trying to blast firebreaks ahead of the flames and preventing citizens from firefighting in their own homes and neighborhoods. The way the authorities handled the fires was a major reason why so much of the city–nearly five square miles, more than twenty-eight thousand structures–was incinerated in one of history’s biggest urban infernos before aerial warfare. Nearly every municipal building was destroyed, and so were many of the downtown businesses, along with mansions, slums, middle-class neighborhoods, the dense residential-commercial district of Chinatown, newspaper offices, and warehouses.

The response of the citizens is less familiar. Here is one. Mrs. Anna Amelia Holshouser, whom a local newspaper described as a “women of middle age, buxom and comely,” woke up on the floor of her bedroom on Sacramento Street, where the earthquake had thrown her. She took time to dress herself while the ground and her home were still shaking, in that era when getting dressed was no simple matter of throwing on clothes. “Powder, paint, jewelry, hair switch, all were on when I started my flight down one hundred twenty stairs to the street,” she recalled. The house in western San Francisco was slightly damaged, her downtown place of business–she was a beautician and masseuse–was “a total wreck,” and so she salvaged what she could and moved on with a friend, Mr. Paulson. They camped out in Union Square downtown until the fires came close and soldiers drove them onward. Like thousands of others, they ended up trudging with their bundles to Golden Gate Park, the thousand-acre park that runs all the way west to the Pacific Ocean. There they spread an old quilt “and lay down…not to sleep, but to shiver with cold from fog and mist and watch the flames of the burning city, whose blaze shone far above the trees.” On their third day in the park, she stitched together blankets, carpets, and sheets to make a tent that sheltered twenty-two people, including thirteen children. And Holshouser started a tiny soup kitchen with one tin can to drink from and one pie plate to eat from. All over the city stoves were hauled out of damaged buildings–fire was forbidden indoors, since many standing homes had gas leaks or damaged flues or chimneys–or primitive stoves were built out of rubble, and people commenced to cook for each other, for strangers, for anyone in need. Her generosity was typical, even if her initiative was exceptional.

Holshouser got funds to buy eating utensils across the bay in Oakland. The kitchen began to grow, and she was soon feeding two to three hundred people a day, not a victim of the disaster but a victor over it and the hostess of a popular social center–her brothers’ and sisters’ keeper. Some visitors from Oakland liked her makeshift dining camp so well they put up a sign– “Palace Hotel” –naming it after the burned-out downtown luxury establishment that was reputedly once the largest hotel in the world. Humorous signs were common around the camps and street-side shelters. Nearby on Oak Street a few women ran “The Oyster Loaf” and the “Chat Noir”–two little shacks with their names in fancy cursive. A shack in Jefferson Square was titled “The House of Mirth,” with additional signs jokingly offering rooms for rent with steam heat and elevators. The inscription on the side of “Hoffman’s Cafe,” another little street-side shack, read “Cheers up, have one on me…come in and spend a quiet evening.” A menu chalked on the door of “Camp Necessity,” a tiny shack, included the items “fleas eyes raw, 98 cents, pickled eels, nails fried, 13 cents, flies legs on toast, 9 cents, crab’s tongues, stewed,” ending with “rain water fritter with umbrella sauce, $9.10.” “The Appetite Killery” may be the most ironic name, but the most famous inscription read, “Eat, drink, and be merry, for tomorrow we may have to go to Oakland.” Many had already gone there or to hospitable Berkeley, and the railroads carried many much farther away for free.

About three thousand people had died, at least half the city was homeless, families were shattered, the commercial district was smoldering ashes, and the army from the military base at the city’s north end was terrorizing many citizens. As soon as the newspapers resumed printing, they began to publish long lists of missing people and of the new locations at which displaced citizens and sundered families could be found. Despite or perhaps because of this, the people were for the most part calm and cheerful, and many survived the earthquake with gratitude and generosity. Edwin Emerson recalled that after the quake, “when the tents of the refugees, and the funny street kitchens, improvised from doors and shutters and pieces of roofing, overspread all the city, such merriment became an accepted thing. Everywhere, during those long moonlit evenings, one could hear the tinkle of guitars and mandolins, from among the tents. Or, passing the grotesque rows of curbstone kitchens, one became dimly aware of the low murmurings of couples who had sought refuge in those dark recesses as in bowers of love. It was at this time that the droll signs and inscriptions began to appear on walls and tent flaps, which soon became one of the familiar sights of reconstructing San Francisco. The overworked marriage license clerk had deposed that the fees collected by him for issuing such licenses during April and May 1906 far exceeded the totals for the same months of any preceding years in San Francisco.” Emerson had rushed to the scene of the disaster from New York, pausing to telegraph a marriage proposal of his own to a young woman in San Francisco, who wrote a letter of rejection that was still in the mail when she met her suitor in person amid the wreckage and accepted. They were married a few weeks later.

Disaster requires an ability to embrace contradiction in both the minds of those undergoing it and those trying to understand it from afar. In each disaster, there is suffering, there are psychic scars that will be felt most when the emergency is over, there are deaths and losses. Satisfactions, newborn social bonds, and liberations are often also profound. Of course, one factor in the gap between the usual accounts of disaster and actual experience is that those accounts focus on the small percentage of people who are wounded, killed, orphaned, and otherwise devastated, often at the epicenter of the disaster, along with the officials involved. Surrounding them, often in the same city or even neighborhood, is a periphery of many more who are largely undamaged but profoundly disrupted–and it is the disruptive power of disaster that matters here, the ability of disasters to topple the old orders and open new possibilities. This broader effect is what disaster does to society. In the moment of disaster, the old order no longer exists and people improvise rescues, shelters, and communities. Thereafter, a struggle takes place over whether the old order with all its shortcomings and injustices will be reimposed or a new one, perhaps more oppressive or perhaps more just and free, like the disaster utopia, will arise.

Of course people who are deeply and devastatingly affected may yet find something redemptive in their experience, while those who are largely unaffected may be so rattled they are immune to the other possibilities (curiously, people farther from the epicenter of a disaster are often more frightened, but this seems to be because what you imagine as overwhelming or terrifying while at leisure becomes something you can cope with when you must–there is no time for fear). There are no simple rules for the emotions. We speak mostly of happy and sad emotions, a divide that suggests a certain comic lightness to the one side and pure negativity to the other, but perhaps we would navigate our experiences better by thinking in terms of deep and shallow, rich and poor. The very depth of emotion, the connecting to the core of one’s being, the calling into play one’s strongest feelings and abilities, can be rich, or even on deathbeds, in wars and emergencies, while what is often assumed to be the circumstance of happiness sometimes is only insulation from the depths, or so the plagues of ennui and angst among the comfortable suggest.

Next door to Holshouser’s kitchen, an aid team from the mining boomtown of Tonopah, Nevada, set up and began to deliver wagonloads of supplies to the back of Holshouser’s tent. The Nevadans got on so well with impromptu cook and hostess they gave her a guest register whose inscription read in part: “in cordial appreciation of her prompt, philanthropic, and efficient service to the people in general, and particularly to the Tonopah Board of Trade Relief Committee…May her good deeds never be forgotten.” Thinking that the place’s “Palace Hotel” sign might cause confusion, they rebaptized it the Mizpah Cafe after the Mizpah Saloon in Tonopah, and a new sign was installed. The ornamental letters spelled out above the name “One Touch of Nature Makes the Whole World Kin” and those below “Established April 23, 1906.” The Hebrew word mizpah, says one encyclopedia, “is an emotional bond between those who are separated (either physically or by death).” Another says it was the Old Testament watchtower “where the people were accustomed to meet in great national emergencies.” Another source describes it as “symbolizing a sanctuary and place of hopeful anticipation.” The ramshackle material reality of Holshouser’s improvised kitchen seemed to matter not at all in comparison with its shining social role. It ran through June of 1906, when Holshouser wrote her memoir of the earthquake. Her piece is remarkable for what it doesn’t say: it doesn’t speak of fear, enemies, conflict, chaos, crime, despondency, or trauma.

Just as her kitchen was one of many spontaneously launched community centers and relief projects, so her resilient resourcefulness represents the ordinary response in many disasters. In them, strangers become friends and collaborators, goods are shared freely, people improvise new roles for themselves. Imagine a society where money plays little or no role, where people rescue each other and then care for each other, where food is given away, where life is mostly out of doors in public, where the old divides between people seem to have fallen away, and the fate that faces them, no matter how grim, is far less so for being shared, where much once considered impossible, both good and bad, is now possible or present, and where the moment is so pressing that old complaints and worries fall away, where people feel important, purposeful, at the center of the world. It is by its very nature unsustainable and evanescent, but like a lightning flash it illuminates ordinary life, and like lightning it sometimes shatters the old forms. It is utopia itself for many people, though it is only a brief moment during terrible times. And at the time they manage to hold both irreconcilable experiences, the joy and the grief.

——

Thanks for listening to The Berkeley Remix. We’ll catch up with next time, and in the meantime, from all of here at the Oral History Center, we wish you our best.

New Special Season of the Oral History Center’s “Berkeley Remix” Podcast

Lately, things have been challenging and uncertain. We’re enduring an order to shelter-in-place, trying to read the news, but not too much, and prioritize self-care. Like many of you, we here at the Oral History Center are in need of some relief.

So, we’d like to provide you with some. Episodes in this series, which we’re calling “Coronavirus Relief,” may sound different from those we’ve produced in the past, that tell narrative stories drawing from our collection of oral histories. But like many of you, we, too, are in need of a break.

The Berkeley Remix, a podcast from the Oral History Center of the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley. Founded in 1954, the Center records and preserves the history of California, the nation, and our interconnected world.

We’ll be adding some new episodes in this Coronavirus Relief series with stories from the field, things that have been on our mind, interviews that have been helping us get through, and finding small moments of happiness.

Our first episode is from Amanda Tewes.

Hello, everyone. This is Amanda Tewes, and I am an interviewer with The Oral History Center. The State of California, including my home in Contra Costa County, is under orders to shelter in place for the foreseeable future, so I am coming to you today from the inside of my closet.

This is a trying time for everyone, but I’ve had the opportunity to stand back and acknowledge my incredible privilege in being able to work from home, in being confident that I can afford my next rent payment, in knowing that I have quality health insurance. I can comfortably practice social distancing because I am not on the frontlines of this pandemic, offering medical care or even trying to feed the hungry and newly-unemployed. In fact, I have friends in these fields, and thanks to them I have a front row seat to how COVID-19 is exacerbating the social problems we ignore every day.

As a historian, living in the time of COVID-19 is a bit surreal. I am constantly thinking about what to record about this moment. What will be important for future generations to know? How will we talk to children about something that could become their first and most formative memories? What moments will prove most monumental? Will we even recognize a turning point when it comes?

I don’t yet know the answers to these questions. I do know that I feel a bit like a boiling frog. Every day — no, every hour — brings new and distressing information, and restrictions that seemed incremental have landed us in a situation I couldn’t even have imagined two weeks ago.

What I can tell you is that even while I am social distancing at home and trying to find ways to reduce anxiety, I am also trying hard to stay connected with the world around me, to absorb all the news — good and bad — and to reach out to those I care about. This is a moment to share our various vulnerabilities and to connect with our neighbors — even virtually.

In that spirit, I want to share with you some of my vulnerabilities as an oral historian in a behind-the-scenes look at a recent interview. As interviewers, I think we push some of the human experience out of our minds when it comes to producing oral histories, because we are — rightly — focused on documenting the stories we record with narrators, and on the historical nature of our work. But, “this is a people business,” as my colleague, Todd Holmes, likes to say, and both the interviewer and narrator bring a lot of baggage into each situation. Sometimes literally.

In November 2019, I traveled to Delaware for an oral history with a woman I was very excited to interview. But even though I’ve lived in Massachusetts, I’m never enthusiastic about traveling during the winter. I’m a California girl through and through.

So with reluctance, I packed my recording equipment and winter coat — the real one, not my NorCal one — and flew across the country.

I have a checkered record in winter air travel, so I’m always nervous about this. But traveling with recording equipment is doubly stressful. I carry on my purse with my computer, as well as my camera and microphones and SD cards. However, I have to check my camera tripod stand and the stand for my portable light. The light itself I try to gently squish into my suitcase, which is difficult when you need to pack bulky sweaters.

You’ve probably guessed where this is going. I flew from Oakland to Philadelphia, but my suitcase did not. I looked around the empty luggage carousel and thought, So I guess this is happening.

True, I was lucky that my tripod bag arrived. This meant that at the very least, I could put my camera on the tripod and conduct an interview. But what about my interview outline nestled safely in my suitcase? What about the carefully-curated professional winter wardrobe I packed for the two days of interview sessions? Oh, those were long gone, the airline company told me. If I was lucky, I would be reunited with them before I left the East Coast.

After racing to the rental car location, I had to find an open store at 10:30 at night. I was woefully unprepared to complete this mission in rural Pennsylvania — or was I in Delaware already? I bought emergency hygiene products and the first sweater I saw that wouldn’t interfere with my lavalier mic.

Before falling into a fretful sleep, I texted my narrator about the situation and the potential for delays for our first session, depending on any lingering issues I faced in the morning. It was fine, she assured me, all would be well.

The next morning after I drove to the interview location in rural Delaware, I parked at the top of a hill and lugged my equipment what felt like a mile in the cold. In fact, my rental car was kind enough to warn me that conditions were freezing.

When I extended my hand in greeting, my narrator started coughing up a storm. Oh God, I thought, is she even going to be able to sit for these interviews? Was the baggage situation an omen? No, she assured me, she had brought supplies like cough syrup and tea. She could make it through.

After two sessions separated by a short lunch, it was apparent that the cough medicine wasn’t working. My narrator was truly sick and soldiering her way through my questions — sometimes forgetting her train of thought. I was also distracted by the outline I printed with a hotel printer clearly in need of new toner. On top of which, I felt so unprofessional in my travel jeans and ill-fitting, new sweater that I found it difficult to feel “authoritative.” All in all, we were a miserable bunch.

I left that interview and drove directly to the airport to the luggage I was assured was waiting for me — maybe, probably, depending on the service personnel who answered the phone. After a two-hour round trip to the airport and my recovered suitcase in hand, I figured the situation could only improve.

But then I woke up the next day to a text from my narrator. Her car wouldn’t start, and she would be late because she needed to pick up a rental car. Why couldn’t we catch a break here?!

When we finally met up, my narrator and I coughed and sputtered our way through the final interview session, hoping that we hit upon the most historically-salient points of her life and work.

I think it’s safe to say this was not my most technically proficient oral history interview. To make matters worse, my narrator was herself a practitioner of oral history. But when I reviewed the transcript from this interview just a month or two later, instead of feeling utterly horrified from a barrage of bad memories, I kept laughing to myself and actually took stock of what I learned from this experience.

I learned to be patient in the face of unexpected and even frustrating interview circumstances. But most importantly, I learned to be patient with myself. Even though I am a professional oral historian, I am also human. Life happens. I don’t always get to be perfect.

And even though this was far from my best oral history interview, it was an accurate snapshot of a moment in both of our lives that influenced the way the story was recorded and how it will be remembered.