New oral history release: Michael R. Schilling

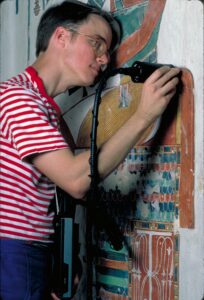

Michael R. Schilling is a chemist and the head of Materials Characterization in the Science Department at the Getty Conservation Institute (GCI), which works internationally to advance conservation practices in the visual arts—broadly interpreted to include objects, collections, architecture, and sites. Since joining the GCI in 1983, Schilling worked on two of the GCI’s flagship world-heritage-site conservation projects: the 3,200-year-old wall paintings in the Tomb of Queen Nefertari in the Valley of the Queens, near Luxor, Egypt; as well as Buddhist paintings in Cave 85 of the Mogao Grottoes located along the ancient Silk Road caravan routes in northwestern China. More recently, Schilling has specialized in developing and teaching new and complex instrumental methods for analyzing the chemistry of materials used by artists and art conservators—from the chemicals in Willem de Kooning’s paints, to the different kinds of plastics in Walt Disney’s animation cels, to the various species of tree saps used in Asian lacquers that were then applied to wood on 18th-century French furniture.

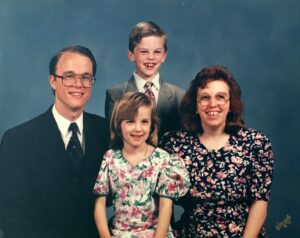

Throughout his oral history, Schilling shared lively stories from his career as a chemist in all three of the GCI’s historic locations while also discussing his family background, his education, the influence of key mentors, as well as the importance of his Christian faith to his marriage and fatherhood of two children. Schilling addressed how he reconciles his Christian faith with his career as a research scientist and rejects the notion of an inherent conflict between science and religion. Schilling’s oral history, which recorded nine hours of dialog across four interview sessions all conducted in April 2019, produced a 234-page transcript that includes an appendix with family photographs and images from Schilling’s work in the GCI.

Michael R. Schilling was born on December 4, 1957 in Los Angeles, California, where he has lived his entire life. Schilling was the first in his family to complete college and earned both his Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees in Chemistry at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona. Schilling married Cherrie Carr in 1982, and they welcomed to the world their children Nicolas and Kate in 1985 and 1988, respectively. In 1983, Schilling began work in the GCI as an Assistant Scientist. He remains the only Getty staff member who worked in all three GCI locations: at the Getty Villa laboratory near Malibu; at the Marina del Rey facility near Venice Beach; and now at the beautiful Getty Center in the Brentwood hills, which includes the GCI’s Materials Characterization laboratory that Schilling now oversees.

In addition to detailing the history of art and its curation for the Getty Trust Oral History Project, Schilling’s interview contributes to the Oral History Center’s vast collection on science and technology. In particular, Schilling described—in accessible layman’s terms—his creative use of pyrolysis–gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (or Py-GC/MS), which rapidly heats a sample to produce small molecules that are then separated and identified by their weight. Schilling outlined a few high-profile examples from his Py-GC/MS process development, including the chemical analysis and therefore improved preservation of aged and peeling Walt Disney animation cels; the analysis of modern paints, particularly those mixed by Dutch-American artist Willem de Kooning for his abstract expressionist works; and especially Schilling’s contributions to new and minimally invasive methods for identifying and analyzing the surprising diversity of tree saps used in Asian lacquers for wood that French furniture-makers adored in the 1700s. The latter project for analyzing Asian lacquers has garnered Schilling and his colleagues international renown from curators and conservation scientists in leading art institutions around the world, from Paris to Beijing.

As a conservation scientist, Schilling discussed the intricate analysis tools he assembled to help interpret Py-GC/MS data for his tripart collaborations with art conservators and with art historians/curators. During his oral history interview, Schilling likened their tripart work in cultural heritage to a three-legged stool:

“Curators and art historians are one leg of the stool. They understand the artist, the environment that he or she was in, attitudes and motives and meanings, the life story of the artist, and traumas that artists go through that affect the art that they make. … What they contribute, then, provides incredible depth and breadth to a study of a particular artist. … [The] Conservator, then, is—they’re artists in their own right, they’re studio artists. They work to preserve, clean, protect works of art. That’s their job. … [They] try out potential cleaning methods, treatment methods, dirt removal—things like that. Then again, they need to know—to do the best job—they need to know the chemistry of what it is that they’re treating. That’s when they come to conservation scientists like me.

Art history, conservation, conservation science—we all work together to understand cultural heritage better. We’re each bringing our own unique backgrounds and perspectives and points of view to bear when we’re sitting in front of a work of art, saying ‘Let’s understand it better.’ … So, understanding the art and how it was created, why it was created, where it was created, for what reason is important. Understanding how it’s changed, what its chemistry is, what’s happening right at the surface where a lot of the conservation treatments happen—that’s necessary in order to come up with and devise a safe and ethical treatment that can be applied to protect it, and restore some of its original appearance, make it more durable, last longer for future generations. You need all of that knowledge to really tell the entire story of an object or an artifact.”

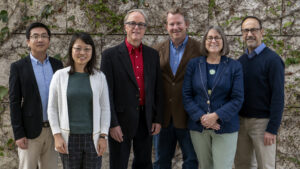

We are very pleased to now publish Michael R. Schilling’s oral history. Many thanks to the J. Paul Getty Trust, which partnered with the Oral History Center in 2015 to establish the ongoing Getty Trust Oral History Project. This joint venture is part of the Getty’s broader mission to expand knowledge and appreciation for art. One of several foci of the Getty Trust Oral History Project features interviews with longtime Getty staff members, art conservators, as well as trustees who made significant contributions to the field and had an impact on the direction of the Getty Trust, often at pivotal moments. Michael Schilling exemplifies a longtime Getty staff member who continues to make significant contributions to his field of conservation science.

You can read Michael Schilling’s interview here:

— Roger Eardley-Pryor, Ph.D.