Earth Sciences and Map Library

GIS & Mapping Community of Practice meetup on Oct. 17

Join us for the next campus GIS & Mapping Community of Practice meetup on October 17 from 2-3 pm! This month’s meetup will take place virtually on Zoom. Register to receive the link.

This informal meetup offers participants an opportunity to get to know other people using mapping tools and techniques across campus, regardless of discipline. Whether you’re just getting started exploring GIS & Mapping or a seasoned pro (or anywhere in between!), all are welcome to participate in the GIS & Mapping Community of Practice. Bring your questions and get excited to meet fellow mappers!

This informal meetup offers participants an opportunity to get to know other people using mapping tools and techniques across campus, regardless of discipline. Whether you’re just getting started exploring GIS & Mapping or a seasoned pro (or anywhere in between!), all are welcome to participate in the GIS & Mapping Community of Practice. Bring your questions and get excited to meet fellow mappers!

Let us know if you’re interested in sharing this month (or at a future meetup) during our community “show and tell,” and also what topics you’re interested in learning about, by completing the GIS & Mapping Community of Practice Interest Form.

Workshop: Creating Web Maps with ArcGIS Online

Creating Web Maps with ArcGIS Online

Thursday, October 13th, 11:10am – 12:30pm

Online: Register to receive the Zoom link

Susan Powell

Want to make a web map, but not sure where to start? This short workshop will introduce key mapping terms and concepts and give an overview of popular platforms used to create web maps. We’ll explore one of these platforms (ArcGIS Online) in more detail. You’ll get some hands-on practice adding data, changing the basemap, and creating interactive map visualizations. At the end of the workshop you’ll have the basic knowledge needed to create your own simple web maps. Register here

Upcoming Workshops in this Series – Fall 2022:

- The Long Haul: Best Practices for Making Your Digital Project Last

- Copyright and Fair Use for Digital Projects

Please see bit.ly/dp-berk for details.

Escape the Earth Sciences & Map Library!

Last year we challenged undergraduates in the Earth & Planetary Sciences and Geography Departments to “escape” from the library by answering a series of questions related to the library’s platforms and services.

The Virtual Escape Room is back again this fall!

Details

ENTER THE ESCAPE ROOM

The Escape Room is open August 22 – September 15, 2022.

The Escape Room is restricted to UC Berkeley affiliated students, staff and faculty. A “berkeley.edu” email address is required to participate.

History

Following the pandemic closures, the Earth Sciences & Map Library reopened in August of 2021. With the start of that new academic year, the Earth Sciences & Map Library staff wanted to welcome back students and remind them of our available library services and spaces. Read about the creation of the 2021 Escape Room in this blog written by a member of the Earth Sciences & Map Library staff.

Updates & Audience

The 2022 Virtual Escape Room continues last year’s Stranger Things theme with relevant updates to reflect changes in the library catalog as well as staffing and hours updates.

The Escape Room is open to all, but targets undergraduates taking EPS and Geography courses. In order to encourage camaraderie among departments housed within McCone Hall, affiliated students, faculty, and staff are encouraged to participate in the Escape Room’s simultaneous Battle of McCone competition. The main majors–Earth and Planetary Sciences and Geography–with the highest number of players will earn bragging rights as the winner of the friendly competition!

Try it!

Reading about something is never the same as a hands-on experience. Now that you have read all about our virtual escape room try it out for yourself! Only students are eligible for prizes, but all @berkeley affiliates are welcome to participate!

Questions?

We welcome questions and comments about the Earth Sciences & Map Library Virtual Escape Room. Email eart@library.berkeley.edu or tweet us @geolibraryucb

The Man who anchored Ukraine in the West: Mykhailo Hrushevsky and the historical geography of Eastern Europe

I remember sitting in a lecture hall at the University of Hamburg in 1986 during my sophomore year. Friends had told me to come early and I watched as every single seat gradually filled up. There was a lot of chatter.

A middle-aged man stepped onto the podium, Klaus-Detlev Grothusen, a scholar of Eastern European history. Two graduate assistants set up a record player, unrolled a wall map, left a pile of books on his lectern. Grothusen was a man who loved what he was doing. Within the first 20 minutes of his ”Introduction to East European History” he had already fit in extended passages from Gogol’s Dead Souls and played a recording of a Ukrainian children’s song to illustrate his points. The students were laughing.

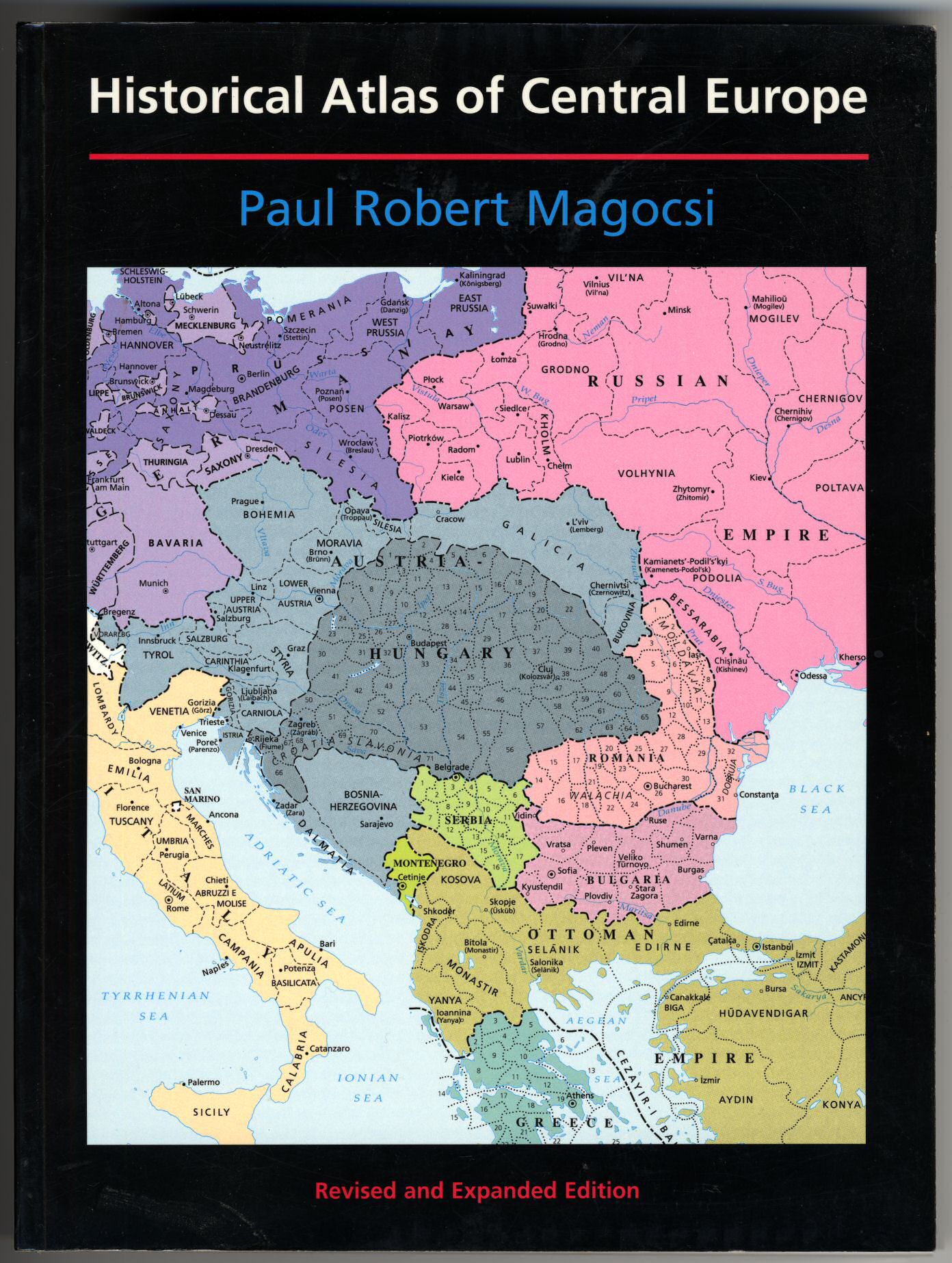

Then Grothusen switched gears and put on his analytical hat. The essential building blocks of East European history, he argued, were the histories of the multiethnic empires that had long dominated the region. Grothusen pointed them out on the wall map. He pointed to the Ottoman Empire which controlled much of the Balkans. Then he looked at the center of the map, focused attention on the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. It was surrounded by three dynastic empires, Tsarist Russia, the Austrian Habsburg Empire, and the Kingdom of Prussia, whose leaders would later construct and dominate the German Empire. The wall map illustrated how those three powers carved up the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in three partitions in the late eighteenth century (1772, 1793, 1795). Grothusen discussed that in some detail.

In Central and Eastern Europe, nation states were latecomers. Many only appeared on the map after the Balkan Wars (1912-1913) and the end of World War I (1918-1919). Some of those East European nation states disappeared again, when the Soviet Union revealed its imperial ambitions. In 1986, Grothusen argued that those imperial ambitions were still very much alive.

Some historical atlases tell this story well. Paul Robert Magocsi, the John Yaremko Chair of Ukrainian Studies at the University of Toronto, authored one of my favorites. The cover illustration of his Historical Atlas of Central Europe , first published in 1993, and now republished in a third edition in 2018 by the University of Toronto Press, gave me pause earlier this week. It shows Central Europe in 1910, on the eve of the Balkan Wars, still dominated by multiethnic empires.

Russian imperial historians, men like Nikolay Karamzin, Sergey Mikhaylovich Solovyov, Vasily Osipovich Klyuchevsky, and Mikhail Petrovich Pogodin, long ago identified the medieval Kyivan Rus’ as the first authentic state of the Eastern Slavs and laid claim to its legacy. The demise of the Kyivan state, they argued, meant that the center of political gravity shifted far to the northeast, away from Kyiv, to the Central Russian Principality of Vladimir-Suzdal. Initially, the rulers of the town of Moscow were just bit players, overshadowed by their more powerful neighbors, first Suzdal, then Vladimir, then Tver. In the 15th century, however, these historians declared, Moscow finally stepped out of the shadows to fulfill its imperial destiny: After the fall of Constantinople in 1453, court scribes proclaimed that the Tsarist autocracy had a valid title to be the successor of the Roman and Byzantine empires. Moscow thus stepped into her new, self-appointed role as the “Third Rome.”

The tsar himself, the embodiment of sovereign authority, stood at the center of Moscow’s autocracy. By the early 18th century, the tsar claimed to be the “Emperor and Autocrat of All the Russias.” And those ”Russias” were carefully enumerated, first and foremost Great Russia (Velikaya Rossiya or Velikorossiya), the territorial core of the Grand Duchy of Moscow; secondly White Russia (Belaya Rossiya), what is still called Belarus today; and finally Little Russia (Malaya Rossiya or Malorossiya), today the independent country of Ukraine.

Vladimir Putin has seized upon this carefully crafted story in his speeches and writings, because it provides a useable national past and seemingly, in his eyes, historical legitimacy for his dangerous and murderous pipedreams of reviving the Russian imperium. According to Putin all Eastern Slavs are essentially Russians, “one people,” a “yedinyi narod.” Fiona Hill eloquently questioned these claims in a recent Politico interview, singling out Putin’s vision of a “Russky Mir” or “Russian World.” Putin and Sergey Lavrov have long argued that Ukraine does not really exist, that its national territory is properly identified as “Novorossiya,” or “New Russia.” Both deny the right to self-determination to Ukrainians.

How do we answer that? Where can we look for an answer? The very idea of what Ukraine represents is wrapped up in another historical narrative, one that was carefully crafted by the leader of the Ukrainian national movement, the historian and statesman Mykhailo Serhiiovych Hrushevsky (1866-1934). As a young scholar, with his published thesis in hand, Hrushevsky was handed a tremendous gift, he was appointed chair of Ukrainian history at Lviv University. This was a newly created position, the very first one of its kind.

Lviv, that great western Ukrainian city, was at that time located in the easternmost reaches of the Habsburg Empire’s province of Galicia. It was the seat of key institutions which spearheaded the Ukrainian cultural revival, the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, the Shevchenko Scientific Society, and also the Prosvita society, founded in 1868 and dedicated to spreading literacy and education in the Ukrainian language.

Lviv was about the only place where Ukrainian national aspirations could be publicly voiced at this time and Hrushevsky seized that chance. In 1897 he was elected president of the Shevchenko Scientific Society, and rebuilt it to function as a Ukrainian Academy of Sciences-in-exile, with popular and scholarly journals, a publishing house, a library, and a museum.

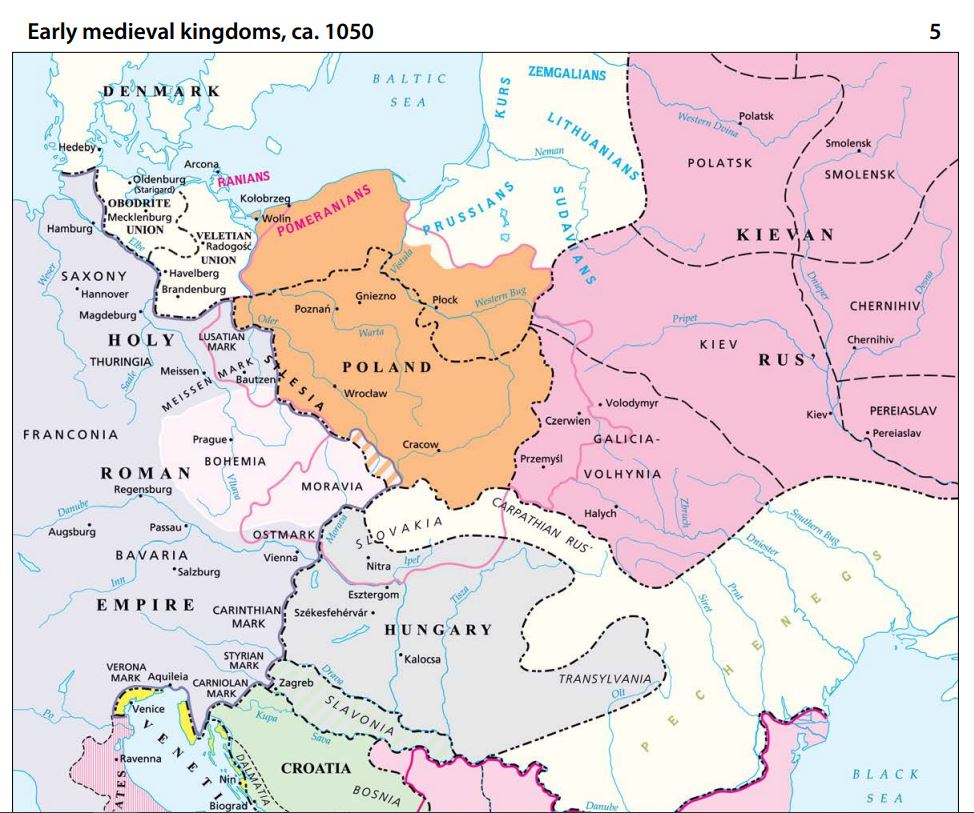

As a historian and ethnographer, Hrushevsky reconstructed the story of Ukraine’s past, most notably in his magisterial ten-volume History of Ukraine-Rus’, the first major synthesis of Ukrainian history. The first volume appeared in 1898, the final one was published posthumously, in 1937. Hrushevsky summarized his key ideas in an article in 1904, “The Traditional Scheme of ‘Rus’ History and the Problem of a Rational Ordering of the History of the Eastern Slavs.” This seminal essay immediately ignited heated debates because Hrushevsky claimed what should have been obvious all along, that the Ukrainians, Belarusians and Russians had distinct identities and histories, which deserved separate historical treatments.

The two principalities of Galicia and Volhynia made up the the westernmost part of the Kyivan Rus’ and were united in 1199 by Grand Prince Roman the Great of Kyiv (Source: Magocsi’s Historical Atlas of Central Europe).

Hrushevsky firmly anchored Ukraine’s history in the West: He showed that the Kyivan Rus’, with its distinct political-administrative structure, socio-economic base, culture and laws, was the creation of southern tribes of the Eastern Slavs. After the disintegration of the Kyivan Rus’, Hrushevsky looked to the southwest and identified a new center of political gravity there. He tied the history of Ukraine to the Principality of Galicia-Volhynia (1199-1253) and the Kingdom of Ruthenia (1253-1349) which emerged out of it. The center of the Ruthenian kingdom, ultimately conquered by Lithuanians and Poles, and absorbed by the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, survived relatively intact as the Ruthenian domain of the Polish Crown, it formed the Ruthenian Voivodeship. Hrushevsky thus tied the history of Ukraine (and likewise the history of Belarus) to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and not to the Tsarist autocracy.

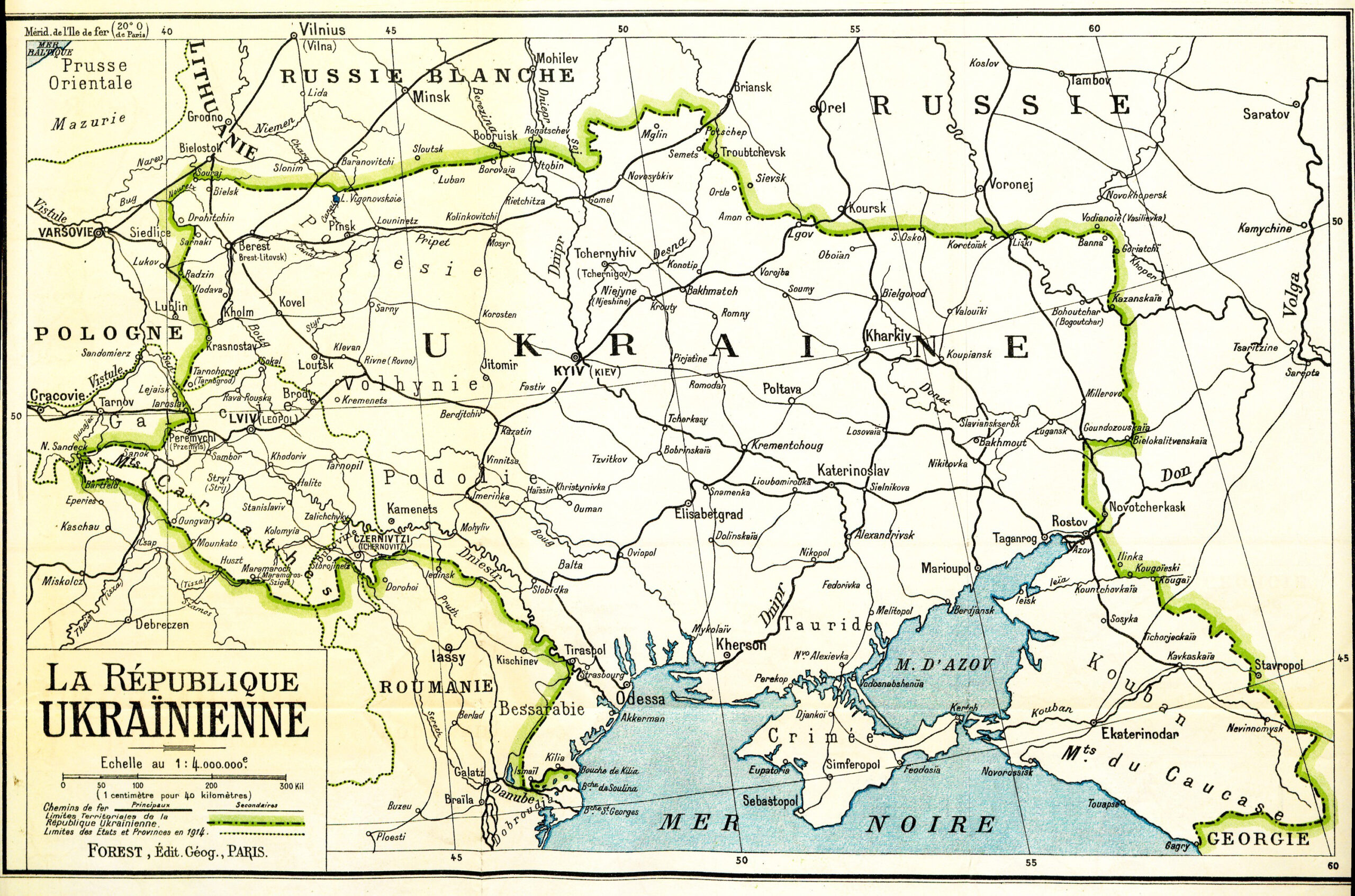

The unraveling of Tsarist power during the February Revolution, the first stage of the Russian Revolution in 1917, opened new possibilities. The Tsentralna Rada (Ukrainian Central Council) in Kyiv, the All-Ukrainian council (soviet) of the Ukrainian People’s Republic, elected Hrushevsky as chairperson. Under his direction, this body soon became the revolutionary parliament of Ukraine. Hrushevsky joined the newly formed Ukrainian Party of Socialist Revolutionaries, the majority party. In June 1917, the Ukrainian People’s Republic declared its autonomy and was recognized by the Prime Minister of the Russian Provisional government, Alexander Kerensky. In January 1918, after the Bolsheviks took control in Russia, the Rada proclaimed Ukraine an independent and sovereign state. Three weeks later, the New York Times published excerpts from Hrushevsky’s “Ukraine’s Struggle for Self-Government” and introduced him as “one of the new republic’s most eminent men.” As a radical democrat Hrushevsky successfully opposed a Bolshevik takeover and in April 1918 he was elected president, after the Rada adopted a Ukrainian constitution. But Hrushevsky was soon overthrown in a coup d’état by conservative power brokers. The Ukrainian Bolsheviks decamped for Kharkiv, Ukraine’s second-largest city, and established a rival government there, the Ukrainian Soviet Republic, aided by the bayonets of the Red Army. In the end, the Ukrainian War of Independence (1917-1921) ended disastrously for Ukrainians, their country was divided by Poland and the new Bolshevik regime.

Map of Ukraine, showing the country’ proposed borders. Prepared for the Paris Peace Conference at the end of World War I, 1918.

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, also known as Soviet Ukraine, was one of the constituent republics of the Soviet Union. In 1923, its All-Ukrainian Academy of Sciences elected Hrushevsky as full member and he returned to Kyiv. He held the chair of Modern Ukrainian History and edited the journal Ukraïna from 1924 to 1930, the official publication of the historical section of the All-Ukrainian Academy of Sciences. By 1929, with the power of Stalinist operatives on the rise, attacks on Hrushevsky increased, for not adopting official Soviet Marxist interpretations. He was arrested in March 1931, subjected to constant surveillance, and forced to live in Moscow. Like many other Ukrainian intellectuals, most of his students and co-workers were arrested and repressed. Many subsequently died, murdered by the Stalinist regime. Hrushevsky himself died in suspicious circumstances, after what should have been minor surgery, in 1934.

I thought of Klaus-Detlev Grothusen several times these last weeks, how his eyes lit up when he played music composed by Tchaikovsky, or when he read poetry from Taras Shevchenko’s Kobzar, one of the seminal works of Ukrainian literature. But I also remember Grothusen’s discussion of the Stalinist system. He quoted Stalin himself, who tried to legitimize his methods by saying darkly that “Russians need a tsar.”

Stalin and Putin share the belief that coercion and autocracy are essential tools in their tool chest. Ukraine, a country that was brutally repressed by Stalin, is now attacked by Putin who seems determined to liquidate its independence. Ukraine is a viable nation state, Europe’s second-largest country, with 44 million Ukrainian citizens. Let’s all help to make sure Ukraine endures and flourishes.

Can you escape? Virtually reaching out to students through an online escape room

Why an escape room?

Covid-19 altered the lives of people across the world. For the UC Berkeley campus, the virus forced the university to close its doors to students in March of 2020 and almost all of its services went virtual overnight. Today, things on campus are returning to a new normal and students have eagerly returned to campus with instruction shifted to mostly in person. With the start of the new academic year, the Earth Sciences & Map Library staff wanted to welcome back students and remind them of our available library services and spaces. This year was the first time that nearly all of the incoming freshman and sophomore students would be on campus for the first time so the orientation needed to be extra special. Staff decided that one of the best ways to reach out was by creating a virtual library escape room. To incentivize student participation, a gift card drawing was added for contestants. In order to foster a connection between the physical library and students, the escape room used photographs of different locations in the Earth Sciences & Map Library for its background images.

Creation

After a few meetings and discussions, the Earth Sciences & Map Library staff decided that they wanted the escape room to be focused on introducing undergraduate students to the library. Questions were geared towards undergraduates and they were the only contenders entered into the gift card drawing. However, in order to encourage camaraderie with departments in the same building housing the Earth Sciences & Map Library (McCone Hall), graduate students, faculty, and staff were encouraged to participate in the escape room’s simultaneous Battle of McCone competition. The friendly battle involved the two majors located in the McCone Hall building, Earth and Planetary Sciences and Geography. Whichever major had the highest number of players would be dubbed the winner of McCone Hall and receive all bragging rights.

The majority of undergraduate students are Generation Z and library staff wanted to pick a theme for the escape room that would be popular with this generation. They decided on using for their theme the show Stranger Things which is very popular with Gen Z. The script for the escape room started off with the story that the Earth Sciences & Map Library contained a portal to a horrible parallel dimension called the Upside Down Library. In the scenario, students accidentally entered the portal to the Upside Down Library and the only way to escape back to the Earth Sciences & Map Library was to solve all clues in all rooms.

The escape room actually consisted of three separate virtual rooms each containing two clues. The two clues could be found by clicking on an image in the virtual escape room which would then direct the students to a page on the Google Site detailing the clue. In total, students had to enter 6 clues in order to “escape” and make it safely back to the Earth Sciences & Map Library. Each of the clues were based on a resource available either through the greater UC Berkeley Library or at the Earth Sciences & Map Library. The whole escape room was created with a mix of Google products: Google Slides, Sites, and Forms. Google Sites served as the home base and structure for the escape room. Google Slides were used to create different “rooms.” The Students entered answers for the clues in the Google Form.

In order to increase accessibility the font for all text was set at 14 points Arial. Images were checked with the Google Chrome extension Colorblindly for issues that could be encountered by the visually impaired. Each image had ALT text added and content was structured with appropriate headers.

Reception

Promotion of the escape room started on the first day of classes August 25, 2021. Library staff emailed department emails, student groups, and outreach coordinators within the Earth & Planetary Sciences and Geography departments. In addition, they created flyers with short urls and QR codes to post around the library. The virtual escape room was open for roughly 2 weeks and had 63 undergraduate student participants. There was an overwhelming number of Geography students that completed the escape room with 54 undergraduate student players compared to only 9 Earth & Planetary Sciences undergraduate students. Later, staff learned that the reason for the large gap between the undergraduate students in the two majors was from an instructor who assigned the escape room to her class. This was a pleasant surprise!

At the conclusion of the escape room, three students were randomly selected as winners for the gift card drawing. In addition, winning students received a library tote bag. On the same day winners were notified of their gift card, all participants were sent an email survey to gauge their experience with the escape room.

Try it!

Reading about something is never the same as a hands-on experience. Now that you have read all about our virtual escape room try it out for yourself!

Design your own

While this library escape room was geared towards specific majors, the images and questions can be easily altered in order to create other escape room variations. If you have questions/comments about the escape room created by the Earth Sciences & Map Library please email erican@berkeley.edu.

Much inspiration for this escape room came from the numerous libraries that have developed virtual escape rooms. In particular, the University of Toronto Engineering & Computer Science Library and the Cleveland State University virtual escape rooms energized the Earth Sciences & Map Library staff to create their own.

Other virtual escape rooms to motivate you:

Lines of Latitude: German Army Map of Spain 1:50,000 (1940-1944)

Beginning in 1936, a newly-formed German military mapping agency produced a large number of topographic map series covering all parts of Europe at various scales, as well as much of northern Africa and the Middle East.

This organization started out as a back room department of the German Army General Staff, focused on military contingency mapping. But, given the murderous goals of the Nazi regime, it quickly morphed into something else, a military mapping agency which provided planning tools for the Nazi leadership to wage a war of conquest, marked by atrocities and unspeakable crimes.

Berkeley’s Earth Sciences and Map Library owns 20,000 German topographic sheet maps produced by the German Army General Staff’s mapping agency, the Directorate for War Maps and Surveying [= Abteilung für Kriegskarten- und Vermessungswesen]. The Berkeley Library obtained this historically significant collection by participating in the World War II Captured Maps depository program of the U.S. Army Map Service.

A presentation by Wolfgang Scharfe, a geography professor at the Free University of Berlin, at the International Cartographic Conference in Durban in 2003, sheds light on the history of these military map series published by the Directorate for War Maps and Surveying. Scharfe looked at one particular topographic map series covering Spain, published in 2 editions between 1940 and 1944, Spanien 1:50 000.

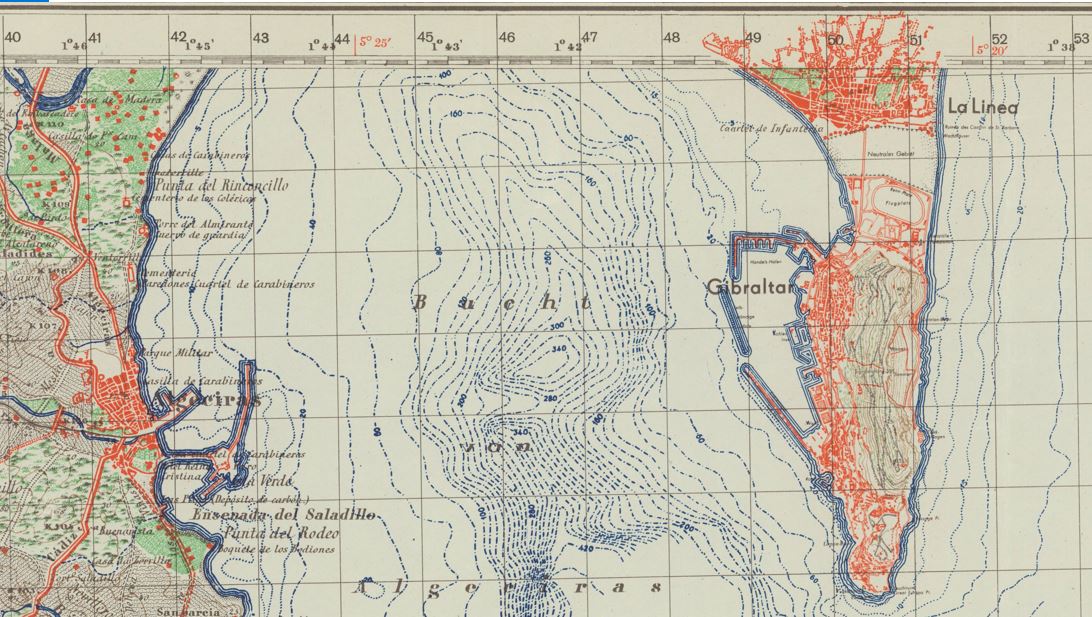

German military cartographers mapped Spain at different scales. The Nazis saw Spanish dictator Francisco Franco’s fascist regime as an ally, but Franco wisely remained neutral during World War II. Initially, the German military mapping of Spain can be seen as part of an effort to bring the Franco dictatorship into the Second World War as a German ally. One goal was the capture of the important British base at Gibraltar, at the entrance to the Mediterranean Sea.

The Bay of Gibraltar, also known as Gibraltar Bay and Bay of Algeciras, identified on the German sheet La Linea-Gibraltar as Bucht von Algeciras. It is located at the southern end of the Iberian Peninsula, near where the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea meet. The sheet is overprinted with the Spanish Lambert Grid, obtained by German military cartographers in an undercover intelligence operation.

The Berkeley Library set of the German Army Map of Spain 1:50,000 consists of 901 sheet maps, accompanied by 3 index maps. It includes two editions of many topographic sheets which cover specific areas of Spain. First Special edition [= Sonderausgabe] sheets were issued between 1940 and 1944, while the second Sonderausgabe sheets were chiefly issued in 1941.

The source map data for the German military maps came from a Spanish map series, the Mapa topográfico de España en escala de 1:50,000 issued by the Direccion general del Instituto Geográfico Catastral y de Estadı́stica.

Scharfe explains that map specialists of the Army Planning Chamber [= Heeresplankammer], the Berlin-based production platform of the Directorate for War Maps and Surveying, copied the Spanish map data. The first edition of this map series (895 published sheets) only contained the Spanish map data. The maps show drainage, roads and trails, railways, vegetation, and other physical and cultural features.

Sheets of the second edition (612 sheets), however, were overprinted with the Spanish Lambert Grid, a geodetic grid which would allow German troops to use the maps to accurately rain down middle and long-range artillery fire on precise locations.

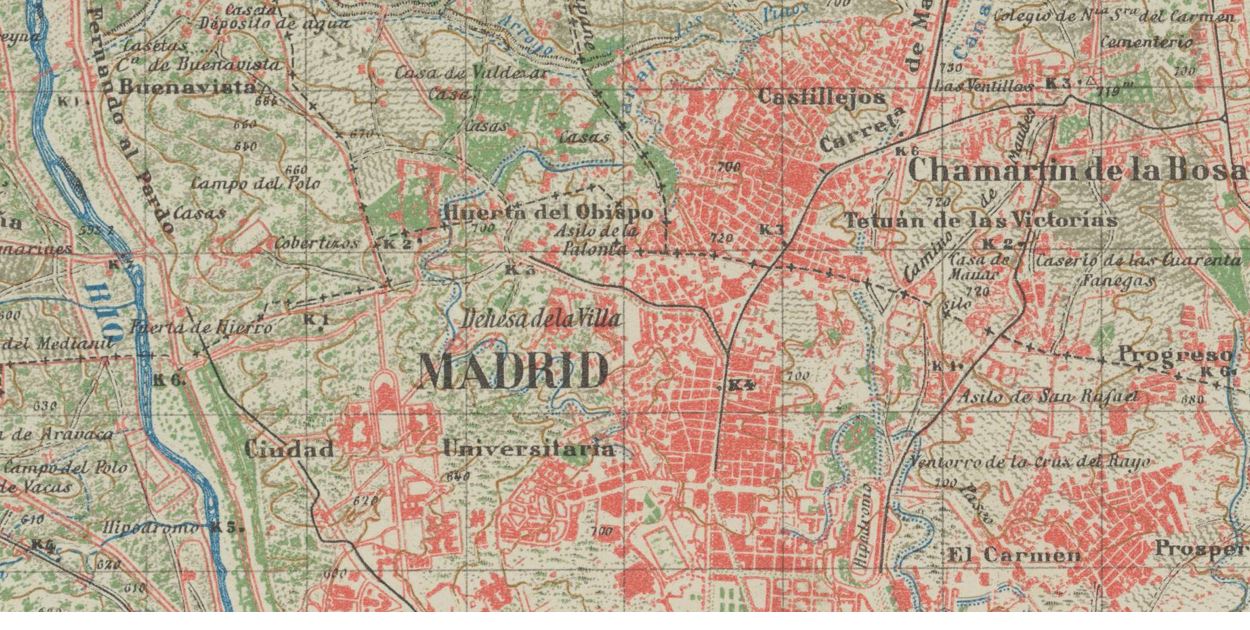

Detail from the Madrid sheet of the German military topographic map series Spanien 1:50 000, published by the Directorate for War Maps and Surveying, a military mapping agency administratively subordinated to the German Army General Staff.

The German military cartographers were able to acquire this secret Spanish military grid data for their own sheets, before that data even appeared on Spanish military maps. This was the result of a German undercover intelligence operation. German agents were able to draw on contacts established when the Nazis aided the fascist Franco dictatorship during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) by sending German troops to Spain, the so-called Legion Condor.

But the story does not end there: Scharfe relates that in 1943, irregular Spanish soldiers raided a German Army depot in Nazi-occupied southern France. They removed sheets of the German Army Map of Spain 1:50,000 with the secret Spanish military grid data. Spanish officials started an official inquiry which undoubtedly further undermined trust between the fascist Franco regime and the Nazis. Spanish diplomatic demands for explanations registered in Berlin proved unsuccessful.

Map Contest 2021 Winners! @ the Earth Sciences & Map Library!

The Earth Sciences and Map Library held our 2nd annual Mapping the Bay Contest! We received a total of 45 map entries from students in Kindergarten through College from around the Bay Area. We doubled our votes; 845 people voted this year for their favorite map! Check out our website and find out which student entry won in each grade category and all of the entries. Thank you to all contestants and to those who voted on the amazing maps!

Find out more about Earth Sciences & Map Library virtual events on twitter!

Lines of Latitude: Martha Krug-Genthe, pioneering woman geographer and author of Valley Towns of Connecticut (1907)

In December 1904, American geographers gathered in Philadelphia to launch a new professional society, the Association of American Geographers (AAG). Geography was a new discipline in the United States. The first geography department had just been established one year earlier, at the University of Chicago. Up to this point, no forum existed for the regular exchange of ideas among professional geographers. The only publication devoted to the dissemination of scholarly geographical research was the Bulletin of the American Geographical Society.

The Association of American Geographers did not serve women geographers well: For much of its early history, the AAG organized male college and university geographers. Standard program features of AAG meetings, for example the prominent “smoker” social, made clear that the presence of women was not always welcome. At the 1915 annual meeting of the AAG, discussions of geographic education were cancelled altogether, to avoid both the topic and having “prim schoolmarms” at the smoker.

Only two women were among the 48 AAG charter members, Ellen Churchill Semple and Martha Krug-Genthe. Semple’s story is well documented, she has become a reference point in the pantheon of American geography, the representative pioneer woman geographer. In contrast, Krug-Genthe’s life has remained largely unexamined, in part because she was an immigrant woman and a sojourner who only spent a decade in the United States. Her professional endeavors are nevertheless illuminating:

Martha Krug-Genthe was the only one of the AAG founders in attendance in Philadelphia with a doctoral degree in geography. A recent transplant from Germany, Krug-Genthe had earned her doctorate at the University of Heidelberg in 1901 under the supervision of Alfred Hettner, a rising star in the profession. Martha’s dissertation examined how hydrographic charts had been used to map ocean currents. She analyzed the Gulf Stream and its northeastward extension, the North American Current, to map the expanding knowledge in the field of oceanography.

Martha Krug-Genthe and her spouse Karl Wilhelm Genthe represented something new, two young married research scientists who both insisted on pursuing professional careers. Karl had first arrived in the U.S. in 1897, after earning his Ph.D. in zoology at the University of Leipzig. In 1901, he transferred to Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut, and ultimately was appointed assistant professor of Natural History. With his professional future somewhat assured, Karl returned to Germany to marry Martha.

Initially, Martha was able to leverage her German credentials. In 1901, just after her arrival in the United States, National Geographic Magazine published her 14-page article surveying the German geography scene. She was able to gain a teaching position at Beacon School in Hartford, a secondary school for young women.

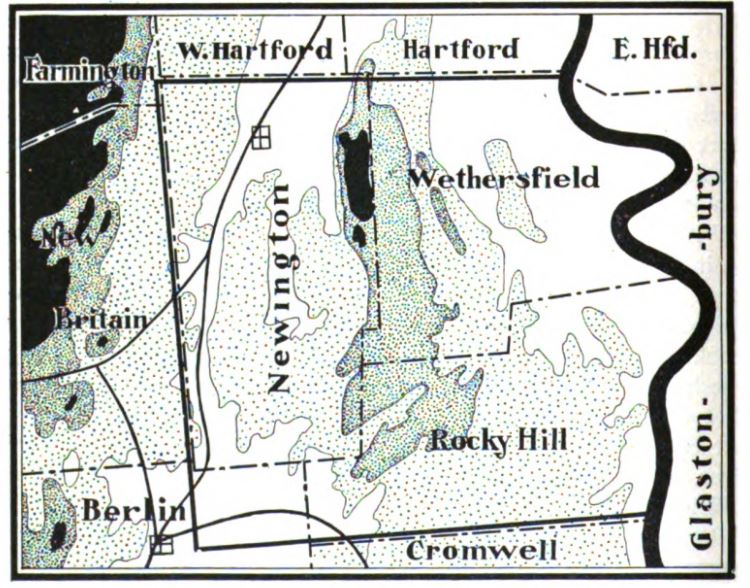

Connecticut’s geography emerged as a particular focus of Krug-Genthe’s research, the natural outgrowth of her work as a secondary school geography teacher. In 1907 the Bulletin of the American Geographical Society published her well-received Valley Towns of Connecticut, the work for which she is most remembered today.

Topography of Newington region, Connecticut River Valley, from Krug-Genthe’s Valley Towns of Connecticut.

This was regional geography, a study of the economic factors driving the evolution of an urban system. Martha used historical sources but also location analysis to explain the rise of Hartford as the pre-eminent center of the Connecticut River Valley.

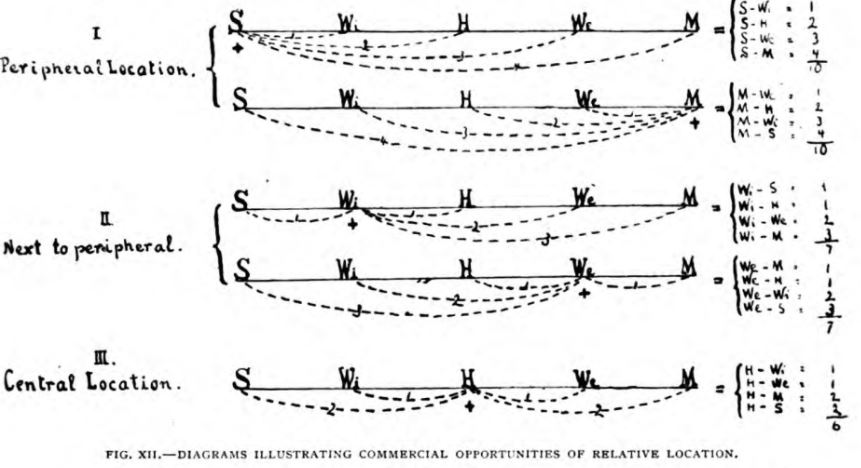

Location analysis diagram from Valley Towns of Connecticut, illustrating Krug-Genthe’s argument how its central location in the Connecticut River Valley favored Hartford (H).

In October 1903 Martha authored an article about geography textbooks for the Geography Teacher. This was the first of a long series of articles written by Krug-Genthe which discussed aspects of geography education in the United States and appeared in German and U.S. geography and science education journals.

The 1904 meeting of the International Geographical Congress Washington, D.C. was the high point of Martha Krug-Genthe’s professional career. Martha was selected to deliver the “Hommage,” an address commemorating Friedrich Ratzel, the pre-eminent cultural geographer of this time. She also presented a paper on “School geography in the United States” in the section on geography and education.

Issues of geographical education had historically been the one gateway open to women geographers who presented at International Geographical Congresses, beginning with a report by Clémence Royer at the Paris Congress in 1875. This was still true for the Washington Congress of 1904: Four of the five women listed in the congress program presented on pedagogical topics.

Martha Krug-Genthe was ultimately appointed associate editor of the Bulletin of the American Geographical Society. That affiliation bolstered her professional credentials, it was her one remaining secure foothold in the world of academic geography. Not surprisingly, the position appears in the author directory of the Encyclopedia Americana next to her name. It legitimized her role as expert.

But excluded from teaching positions at colleges and universities, Martha Krug-Genthe, just like other professional women geographers, increasingly relied on alternate professional networks which consisted of women geographers teaching at normal schools and secondary schools.

A large number of geography teachers in American secondary schools in the early 20th century were women. Professional women geographers were also well-represented among the geography instructors at the normal schools who trained these teachers. By the 1910s, normal schools hired more specialists in geography education, a process that gained momentum as the number and range of geography course offerings increased.

In 1917, shortly after the founding of the National Council of Geography Teachers, its membership roster boasted the names of 645 women, more than two-thirds of the organization’s members. The American Society of Professional Geographers likewise was able to recruit a larger number of women members.

So why did the AAG fail Martha Krug-Genthe and American women geographers? In her 2004 presidential address to the Association of American Geographers Janice Monk provides the answer: “For academic men, including geographers, aspirations for professional standing, research credentials, and disciplinary prestige meant building masculine preserves, the practice and sometimes articulation of values that placed women and men in different places and in places of unequal power.” The male AAG leadership had consciously constructed an exclusionary business model which relegated women geographers to the sidelines.

Lines of Latitude: The Long Shadow of Vienna’s Militärgeographisches Institut (1818-1918)

Beginning in the 1840s, the Kaiserliches und Königliches Militärgeographisches Institut [= Imperial and Royal Military Geographical Institute] of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy published many thousands of quality topographic sheets covering much of Central and Eastern Europe, areas where the Habsburg empire had strategic interests. These sheets did not just survey the territory of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, they also provided solid coverage for neighboring parts of the Ottoman and Tsarist empires.

Building of the Militärgeographisches Institut, parade grounds, Josefstädter Glacis, Vienna, Austria, 1860.

The quality of the Habsburg mapping operation was greatly aided by its adaption of the Bessel ellipsoid which fits especially well to the geoid curvature of Europe. The ellipsoid data published by Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel, a professor of astronomy at the University of Königsberg, in 1841 were then the best and most modern data mapping the figure of the Earth. Because of the recognized high quality of their work, Austrian triangulation parties were admitted into neighboring countries. That work was reflected on Austrian topographic maps covering these areas.

Globe on the roof of the building which housed the Militärgeographisches Institut until 1918.

Globe on the roof of the building which housed the Militärgeographisches Institut until 1918.

The Militärgeographisches Institut issued a number of iconic map series, including the Spezialkarte der Österreichisch-Ungarischen Monarchie im Masse 1:75 000. Eventually, 752 quadrangles of this legendary map series were produced, starting in 1873. After the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire at the end of World War I Austria’s Kartographisches Institut, and Hungarian, Czechoslovak, and German mapping agencies continued to issue updated sheets.

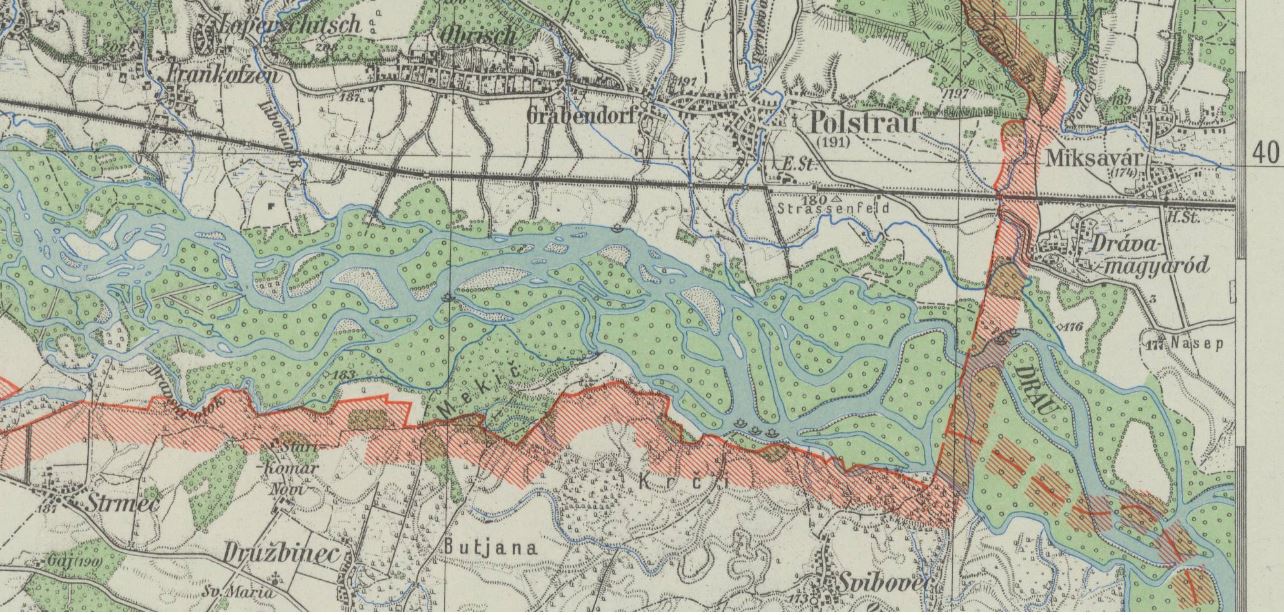

Spezialkarte 1:75 000, sheet # 5456 Pettau shows parts of the Drava river valley, with the borders of Nazi Germany, Hungary, and Croatia, last updated 1943 by a regional survey office of Germany’s civilian mapping agency Reichsamt für Landesaufnahme.

In March 1938 Nazi Germany annexed Austria. This was an important stepping stone in Adolf Hitler’s plans for waging a war of aggression. In Vienna the Nazi regime gained access to important resources and capabilities. German civilian and military mapping agencies moved quickly to incorporate Austrian government institutions active in the fields of surveying and cartography. The new Vienna office of Germany’s civilian Reichsamt für Landesaufnahme absorbed Austria’s well-regarded Kartographisches Institut. The German military incorporated the Austrian Army’s survey office.

Rather than reinvent the wheel German World War II military planners pragmatically worked within an established Austrian framework when they mapped parts of central and southeastern Europe. They continued to issue a number of Austrian map series with a long publishing history which reached far back into the 19th century. The Militärgeographisches Institut, defunct since 1918, cast a very long shadow.

A German military map series with more limited geographical coverage, the Spezialkarte von Österreich, von Ungarn, und der Tschechoslowakei 1:75 000, was published between 1935 and 1944. It was based on 1:75,000 source maps issued 1924-1939 by various Central European mapping agencies. During World War II, Spezialkarte sheets also provided the source map data for various other German military map series which covered large parts of central and southeastern Europe at a scale of 1:50,000.

The UC Berkeley Library acquired 420 sheets of this German military map series through the depository program of the U.S. Army Map Service (AMS) in the 1950s. U.S. Army military intelligence had collected these maps in Germany between October 1944 and September 1945, in the final months of World War II. Today these maps are part of UC Berkeley’s German World War II Captured Maps collection.

Lines of Latitude: German military map series Norwegen/Finnland 1:50 000 (1943-1944)

In 1961 University of California map librarian Sheila T. Dowd took stock: In an article published in the Special Library Association’s Geography and Map Division Bulletin she analyzed the growth of Berkeley’s map collection. Since 1917 its size had quadrupled. Growth came especially in the years following World War II.

Dowd found that the primary driver of that increase in size was Berkeley’s participation in the depository programs of the U.S. Army Map Service (AMS). And she highlighted the impact of the AMS World War II Captured Maps depository program. Ultimately 22,000 German and Japanese World War II maps found their way into Berkeley’s map collection. Most were topographic quadrangles published as part of military map series issued by Axis military mapping agencies.

Sometimes local German military bodies played important roles: Armee-Kartenstelle (mot.) 464 [= Army Maps Post (motorized) 464], served as mapping unit of the 20th German Mountain Army in Lapland during World War II. This area, northernmost Norway and Finland and adjacent areas of the Soviet Union, consisted of forbidding terrain, largely permafrost tundra.

A.K.St. (mot.) 464 produced the German military map series Norwegen/Finnland 1:50 000 to support German mountain troops fighting on the Eastern Front against the Soviet Red Army. One important challenge for the German military mapmakers was the need to document Arctic tundra freeze-thaw cycles. Winters north of the Arctic Circle are long and summers are short. The active layer of permafrost, the topmost layer of soil, thaws in the summer and freezes in the winter. This, of course, greatly affects military operations.

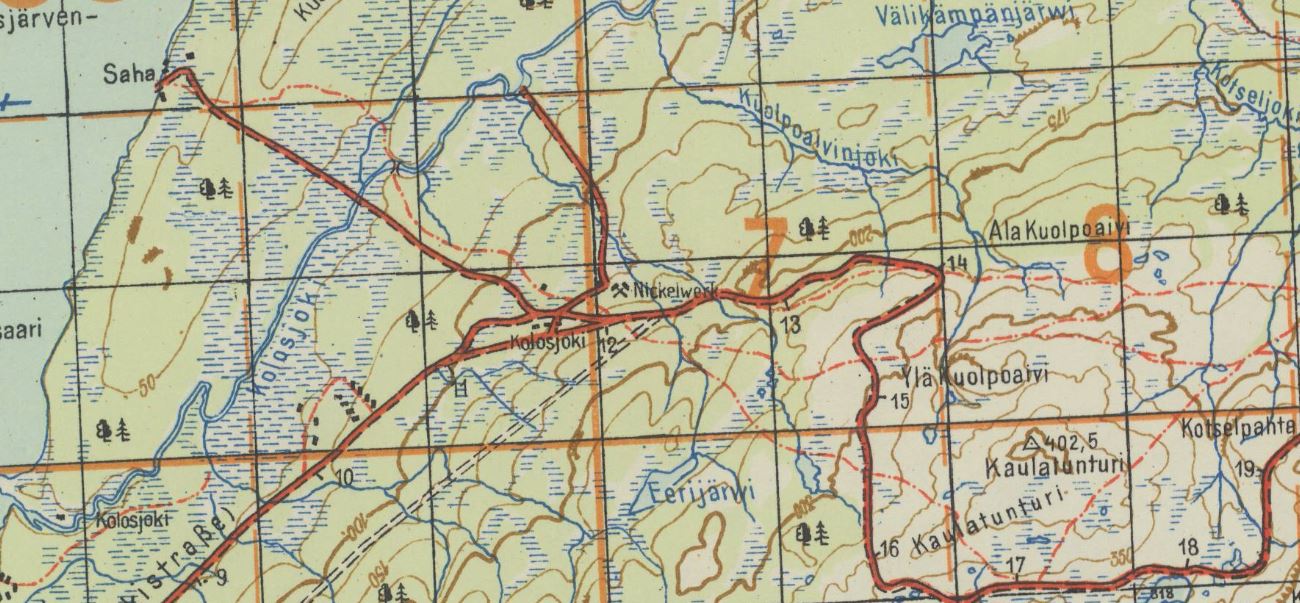

Kolosjoki quadrangle with 2 German military grids, Deutsches Heeresgitter [= German Army Grid], and Heeresmeldenetz [= Army Messaging Web] overprinted in orange. Shows “Nickelwerk,” a mine where nickel, a rare metal used as steel hardener, was extracted. The nickel deposits of northern Finland were important to the German war effort in World War II. This sheet was produced in October 1943.

Kolosjoki quadrangle with 2 German military grids, Deutsches Heeresgitter [= German Army Grid], and Heeresmeldenetz [= Army Messaging Web] overprinted in orange. Shows “Nickelwerk,” a mine where nickel, a rare metal used as steel hardener, was extracted. The nickel deposits of northern Finland were important to the German war effort in World War II. This sheet was produced in October 1943.

In 1942, Armee-Kartenstelle (mot.) 464 had a staff of 53. The unit compiled maps utilizing Finnish, Norwegian and Soviet source map data, aerial photographs of the Luftwaffe, and by performing field checks. It was motorized and equipped with trucks and half a trailer with the mapping and map printing equipment installed. Maps were chiefly printed in color.

A.K.St. (mot.) 464 established a base at Lager Neuer Kolonnenhof, a military camp of about 60-70 barracks, in Rovaniemi, Finland, in January 1942. The unit occupied a headquarters building, two garages for trucks, a workshop, a gas station and other barracks. As the frontlines approached in October 1944 German troops burned down the camp, and also much of the city of Rovaniemi, a war crime, and retreated to northernmost Norway.