Below are ten graphic narrative illustrations created by artist Emily Ehlen that she drew from stories and themes in the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project, or JAIN project, recorded by the Oral History Center, or OHC.

The OHC’s JAIN project documents and disseminates the ways in which intergenerational trauma and healing occurred after the United States government’s mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. The OHC team interviewed twenty-three Japanese American survivors and descendants of the World War II incarceration to investigate the impacts of healing and trauma, how this informs collective memory, and how these narratives change across generations. Initial interviews in the JAIN project focused on the Manzanar and Topaz prison camps in California and Utah, respectively. The JAIN project began at the OHC in 2021 with funding from the National Park Service’s Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant. The grant provided for 100 hours of new oral history interviews, as well as funding for a new season of The Berkeley Remix podcast and for Emily Ehlen’s unique artwork below, all based on the JAIN project oral histories.

We encourage you to use and share Emily Ehlen’s artwork, along with the JAIN project oral history interviews, especially in classrooms when teaching the history and legacy of the World War II incarceration of Japanese Americans. When using these images, please credit Emily Ehlen as the artist (for example, Fig. 1, Ehlen, Emily, WAVE, digital art, 2023, Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley), and see the OHC website for more on permissions when using our oral histories. To save a digital copy of any illustration below for fair use, right click on the image and select “Save Image As…” The text description that accompanies each illustration below aims to provide accessibility for the visually impaired in lieu of Alt-Text limitations, which does not easily accommodate graphic narrative images. In a separate blog post, you can learn more about the artist Emily Ehlen and her processes while creating these dynamic illustrations drawn from the memories and reflections of JAIN oral history narrators.

Artist’s statement

Emily Ehlen’s illustrations for the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project convey compelling narratives and imagery, with impactful shapes and color, by crafting traditionally and translating images into digital pieces. She uses text and imagery to balance the composition and support storytelling elements. Her work encompasses themes of identity and belonging, intergenerational connections, and healing. The collection navigates the impact and experiences of Japanese American incarceration during World War II and its effects on future generations.

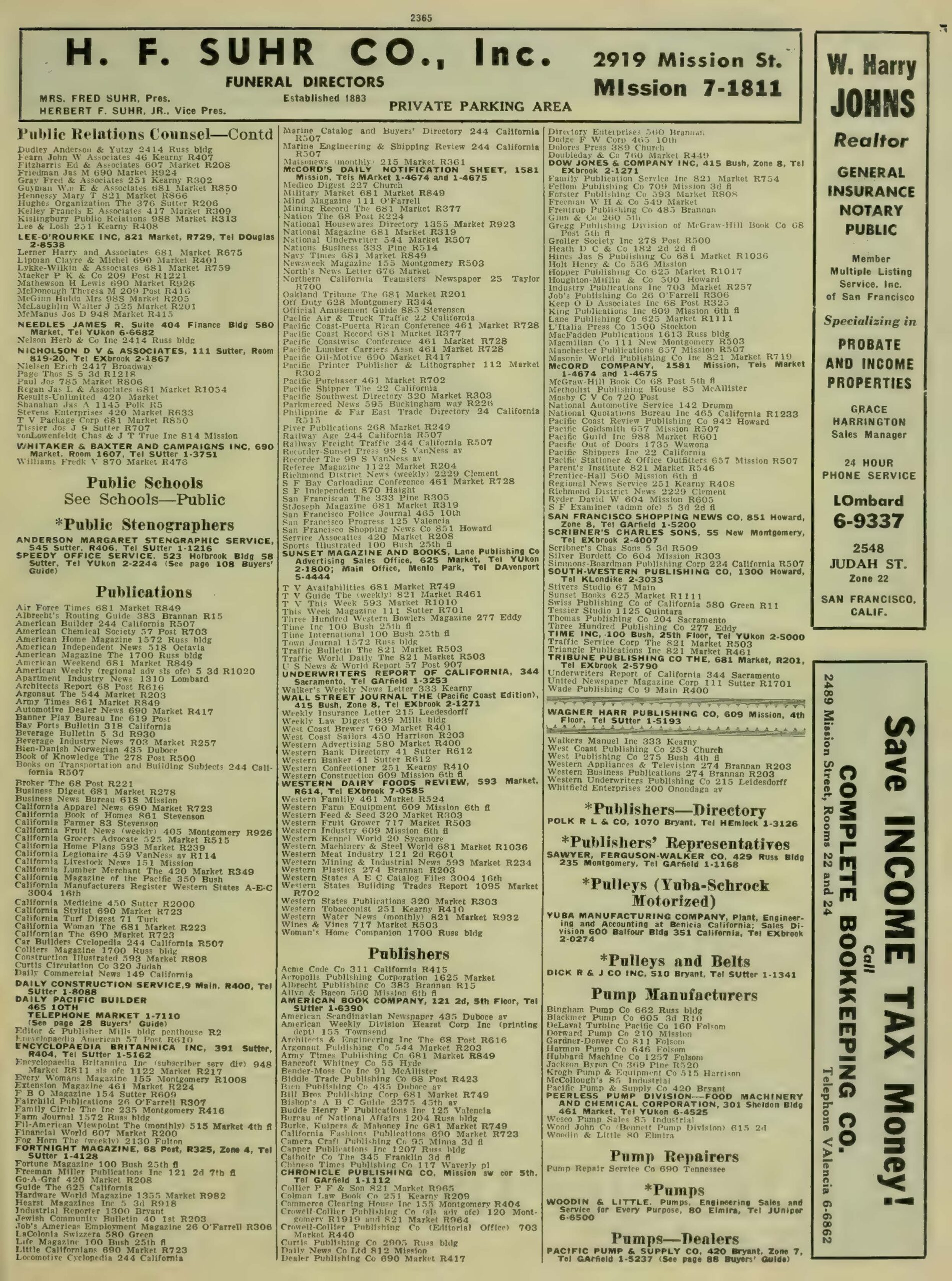

WAVE by Emily Ehlen

This image titled WAVE consists of two panels. The top panel depicts text that relates to the number of generations of Japanese descents surrounding a family portrait using barbed wires as arrows. The text is in romanized Japanese and kanji. It reads: “Issei,” meaning first generation; “Nisei,” meaning second generation; “Sansei,” meaning third generation; “Yonsei,” meaning fourth generation; and “Gosei,” meaning fifth generation. The bottom panel depicts a large wave and guard tower behind barbed wire with text above that reads, “Your generation is just one part of the wave, and you do your best to build what you can for the next generation in your family.”

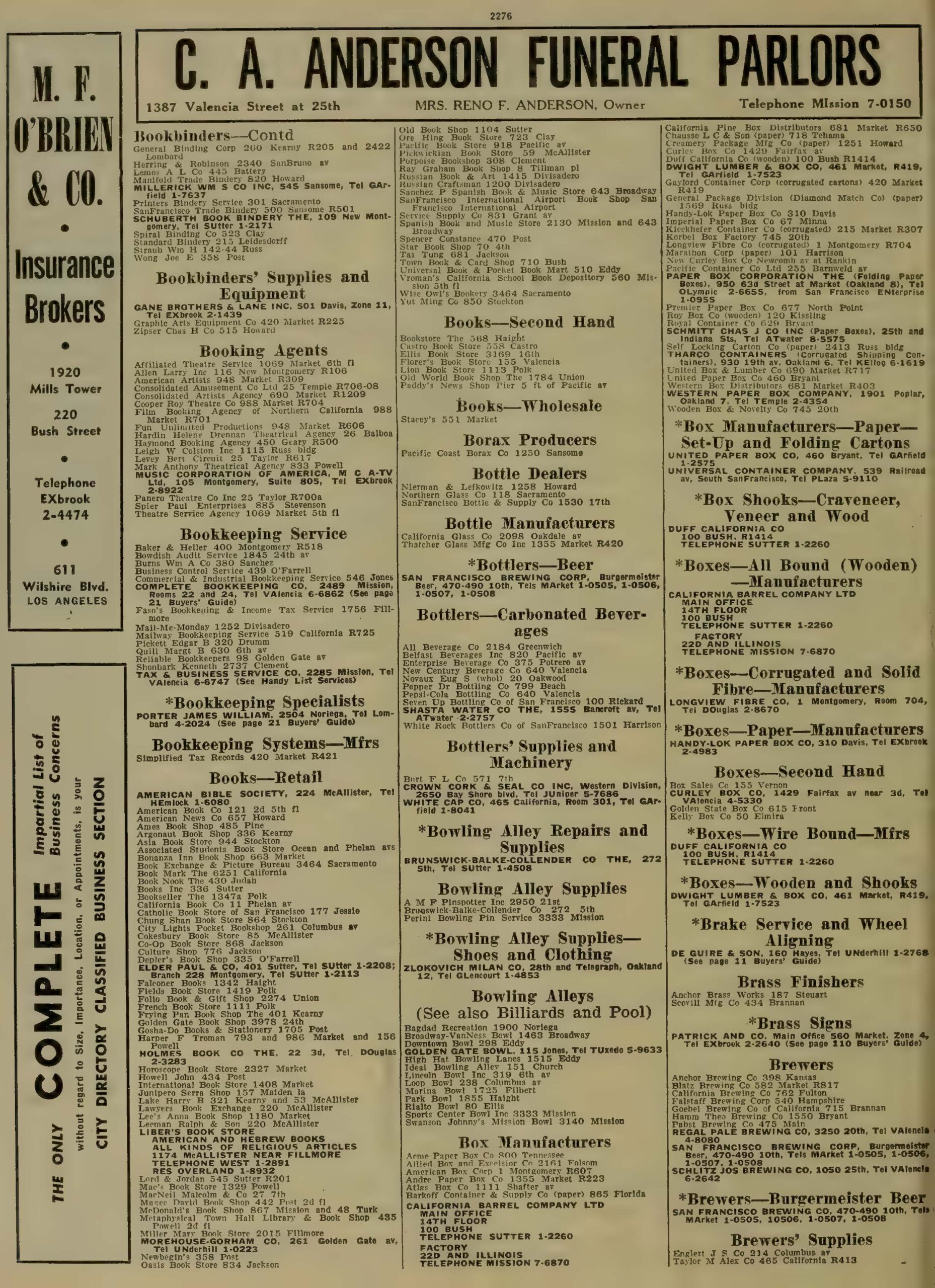

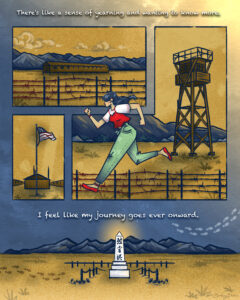

MANZANAR by Emily Ehlen

This image titled MANZANAR consists of four different panels. Each panel depicts a part of an incarceration camp and features barbed wire, the American flag, and the buildings in the camp. Above the top panel there is text that reads, “There’s like a sense of yearning and wanting to know more.” In the middle right panel, a woman in a red top layered over a white T-shirt and green pants runs towards the left of the image. The bottom panel depicts the cemetery monument at Manzanar National Historic Site, with Japanese kanji written on top, which reads, “I REI TO,” or “soul consoling tower.” Below the bottom panel there is text that reads, “I feel like my journey goes ever onward.”

STORIES by Emily Ehlen

This image titled STORIES consists of four panels. The top panel depicts a growing boy talking to his mother. An incarceration camp appears behind the mother. Above this top panel, the text reads, “My mom would not speak of things in camp. Maybe she didn’t want to or couldn’t at the time. It wasn’t ’til I was older did she begin telling me stories of camp.” Under this top panel, the text reads, “I got to know more about my mom, about a part of her life when I wasn’t there.” Two middle panels follow, depicting a green puzzle piece and crying eyes behind barbed wire. The text between these panels reads, “The missing piece she kept. The sadness she concealed.” In the bottom panel, tears from the eyes above fall into a plant on the ground that is growing. The text on this panel reads, “Talking about it didn’t make the pain disappear, but letting her experiences come to light brought a place for healing.”

TEACHER by Emily Ehlen

This image titled TEACHER consists of four panels. The top left panel shows a male teacher next to a chalkboard. The text on the chalkboard reads, “In middle school, we were learning about the Holocaust, and our teacher was telling the whole class like, ‘Well, Jewish people were put in camps…'” The top right panel depicts a raised hand with text that reads, “And I was like, ‘Wait, my grandmother was put in a camp.’ So I raised my hand.” The middle panel depicts a girl sitting at a desk, a male teacher standing, and a large crack between them. On the left of the panel, the girl says, “My grandparents were put in a camp, but they were put in a camp by America.” The text in the large crack reads, “And there was this awkward silence.” The teacher responds, “Well, we didn’t kill people.” The word “kill” has a red strikethrough on it. The bottom panel depicts the girl at the desk alone in the dark. The text reads, “I remember that as the first time I felt like my experience was disparaged or put down, but I was too young to really understand that.” Text on the bottom left indicates these quotations are from Miko Charbonneau’s oral history for the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project.

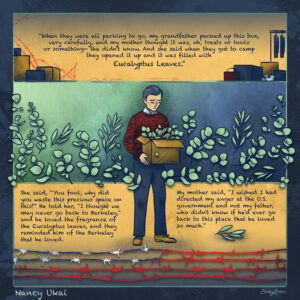

EUCALYPTUS by Emily Ehlen

This image titled EUCALYPTUS consists of three panels. The top panel depicts suitcases and boxes of various sizes, and includes text which reads, “When they were all packing to go, my grandfather packed up this box, very carefully, and my mother thought it was, oh, treats or tools, or something—she didn’t know. And she said when they got to camp and opened it up and it was filled with Eucalyptus Leaves.” The words “eucalyptus leaves” are larger than the other words. In the center, the grandfather stands in front of all of the panels with a box of eucalyptus leaves. He is looking down with a sad expression. The bottom panel depicts some eucalyptus leaves as well as barbed wire that mimics the red, white, and blue of an American flag. This panel includes text which reads, “She said, ‘You fool, why did you waste this precious space on this?’ He told her, ‘I thought we may never go back to Berkeley,’ and he loved the fragrance of the Eucalyptus leaves, and they reminded him of the Berkeley he loved. My mother said, ‘I wished I had directed my anger at the U.S. government and not my father, who didn’t know if he’d ever go back to this place that he loved so much.'” Text on the bottom left indicates these quotations are from Nancy Ukai’s oral history for the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project.

SPLASH by Emily Ehlen

This image titled SPLASH consists of two panels on the top and two on the bottom. The top left panel depicts a younger woman and an older woman in a boat. Text above the top two panels reads, “The U.S. Government told my mother, ‘It is advisable that you move as far away from California as you can. Stay away from other Japanese. Try to become even more American than you think you are, than you already are.'” The top right panel depicts the two women holding hands and standing in the boat. The text below these panels reads,”‘Just quietly go about your business even though this horribly unconstitutional thing has just happened to you and you’ve suffered all this trauma. But try to be American. Try to fit in.'” The bottom left panel depicts a close-up of the women holding hands above the boat and a ripple in the water. Beneath the hands, the text reads, “We were told, ‘Don’t rock the boat, do not make waves.” Beneath the boat, the text reads, “Nonsense. Let’s go make a Big Splash!” The bottom right panel depicts the two women holding hands and jumping into a sea of waves. Text on the bottom left indicates these quotations are from Jean Hibino’s oral history for the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project.

TOPAZ by Emily Ehlen

This image titled TOPAZ consists of four panels. The top panel depicts white stars behind barbed wire in red and blue that mimics the American flag, as well as a guard tower. The next panel depicts footsteps with plants sprouting from the final four steps. To the right of the footsteps, a white paper crane rests on soil. Red and blue barbed wire appears in the background. Text at the bottom of this panel reads, “The path we make will help us and others heal.” The bottom two panels depict barbed wire at the top and bottom, which frame a group of people all holding hands walking to the right. The group of people, which includes a range of ages, spans both panels. The individuals have glowing lights over their hearts. Plants sprout from the bottom of this panel.

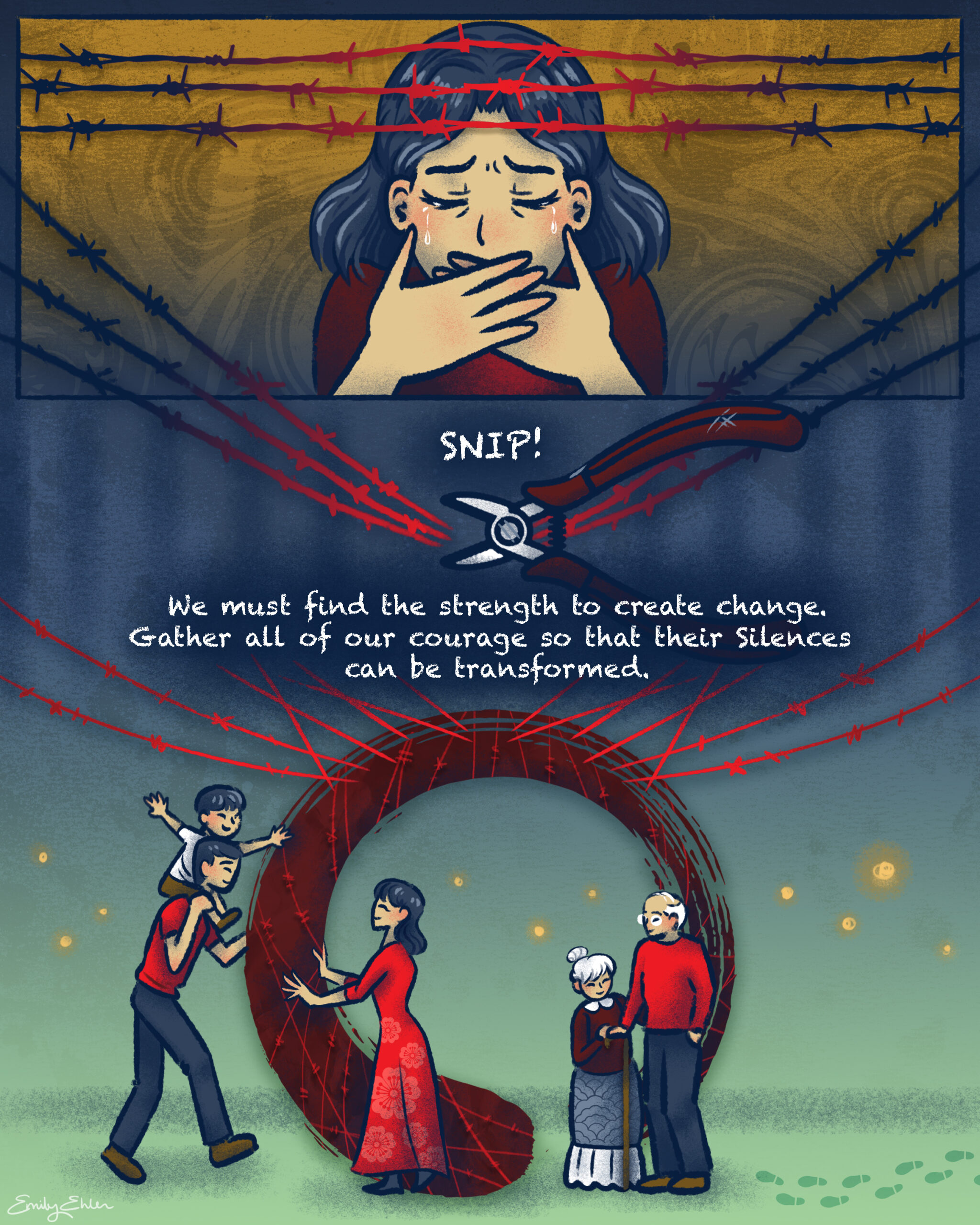

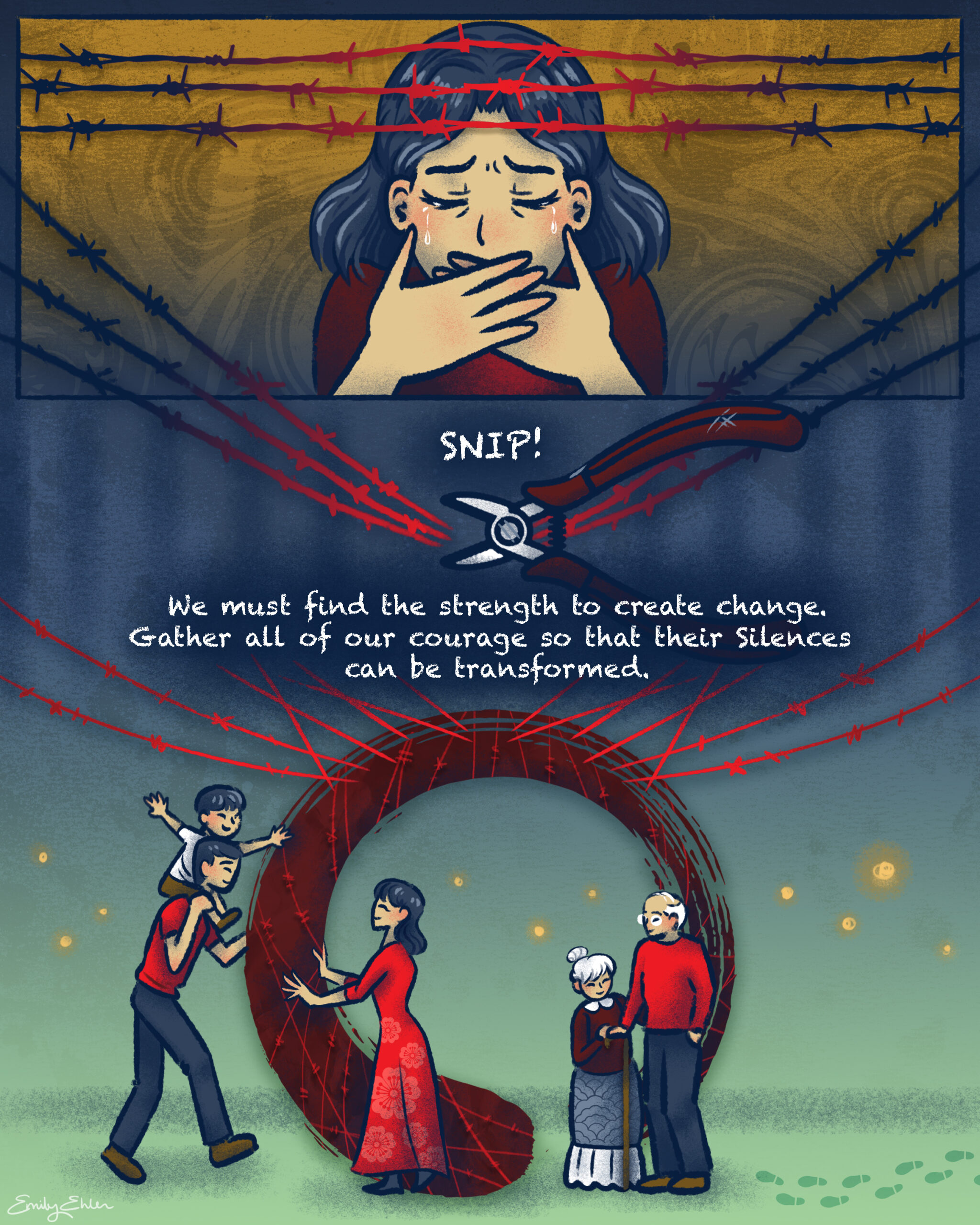

SILENCES by Emily Ehlen

This image titled SILENCES consists of two panels. In the top panel, a woman cries while framed by red barbed wire. The bottom panel depicts wire cutters snipping the red barbed wire. Text reads, “SNIP!” Beneath the barbed wire is text that reads, “We must find the strength to create change. Gather all of our courage so that their silences can be transformed.” Beneath this text is a scene depicting a man with a child on his shoulders moving toward a woman with open arms. To the right of them are an elderly woman and man. Behind the group of people, there is a large, red circular ensō formed from the barbed wire. Glowing lights also appear in the background.

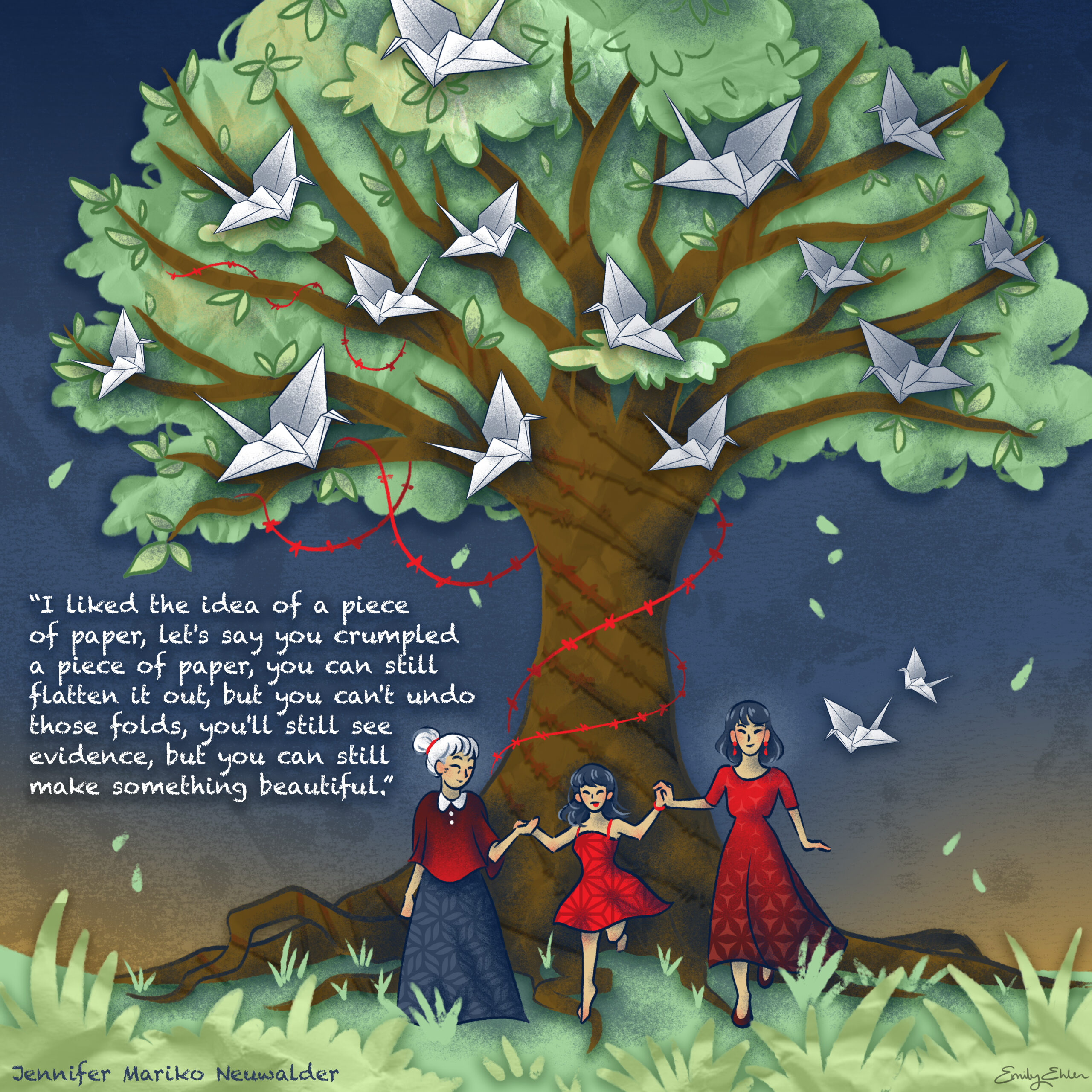

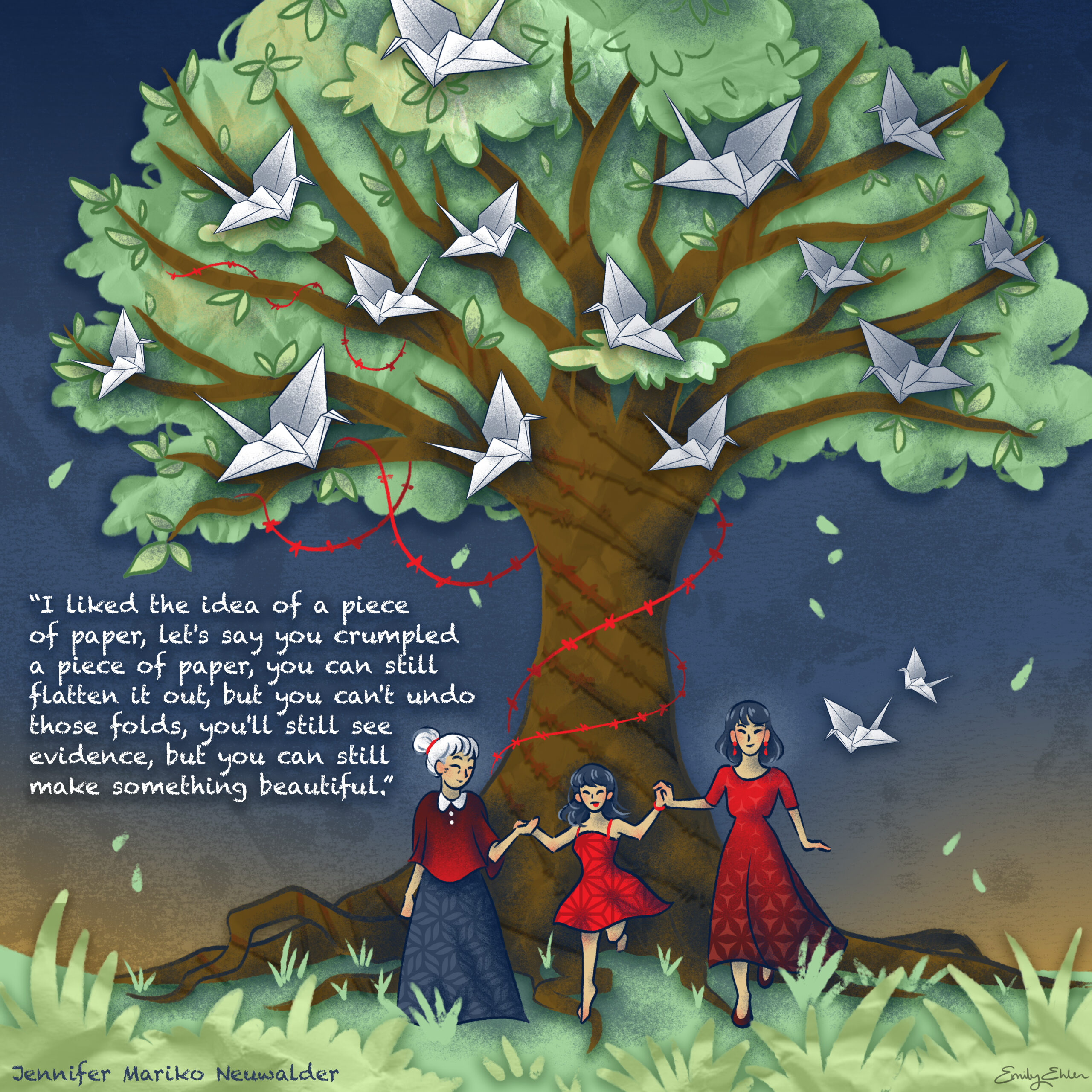

TREE by Emily Ehlen

This image titled TREE consists of one panel, depicting three women of different generations holding hands in front of a large tree wrapped in red barbed wire and filled with white paper cranes. This image includes text which reads, “‘I liked the idea of a piece of paper, let’s say you crumpled a piece of paper, you can still flatten it out, but you can’t undo those folds, you’ll still see evidence, but you can still make something beautiful.” Text on the bottom left indicates these quotations are from Jennifer Mariko Neuwalder’s oral history for the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project.

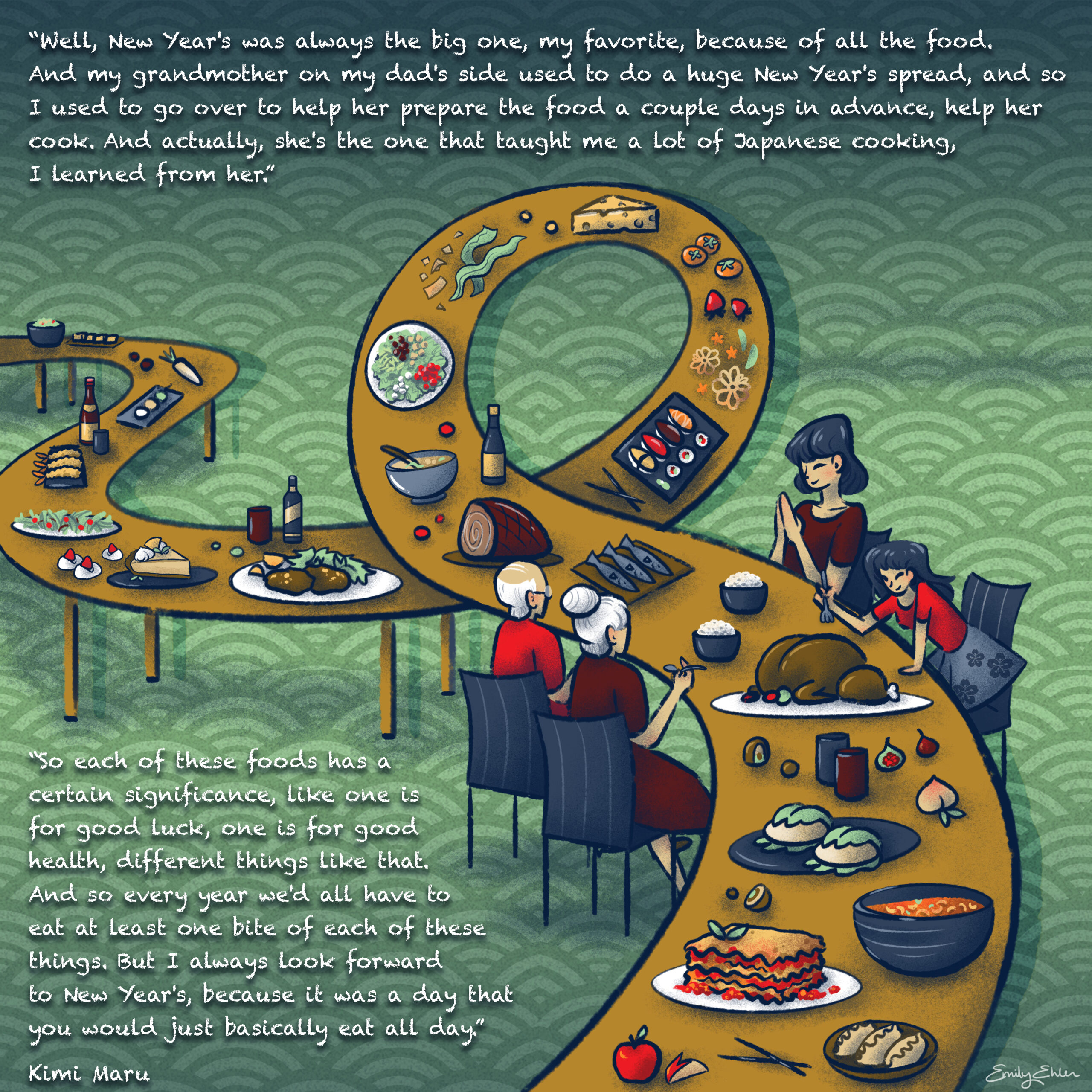

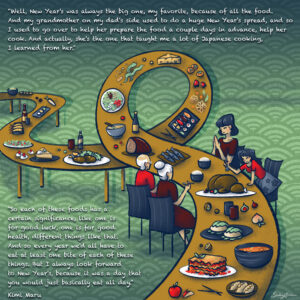

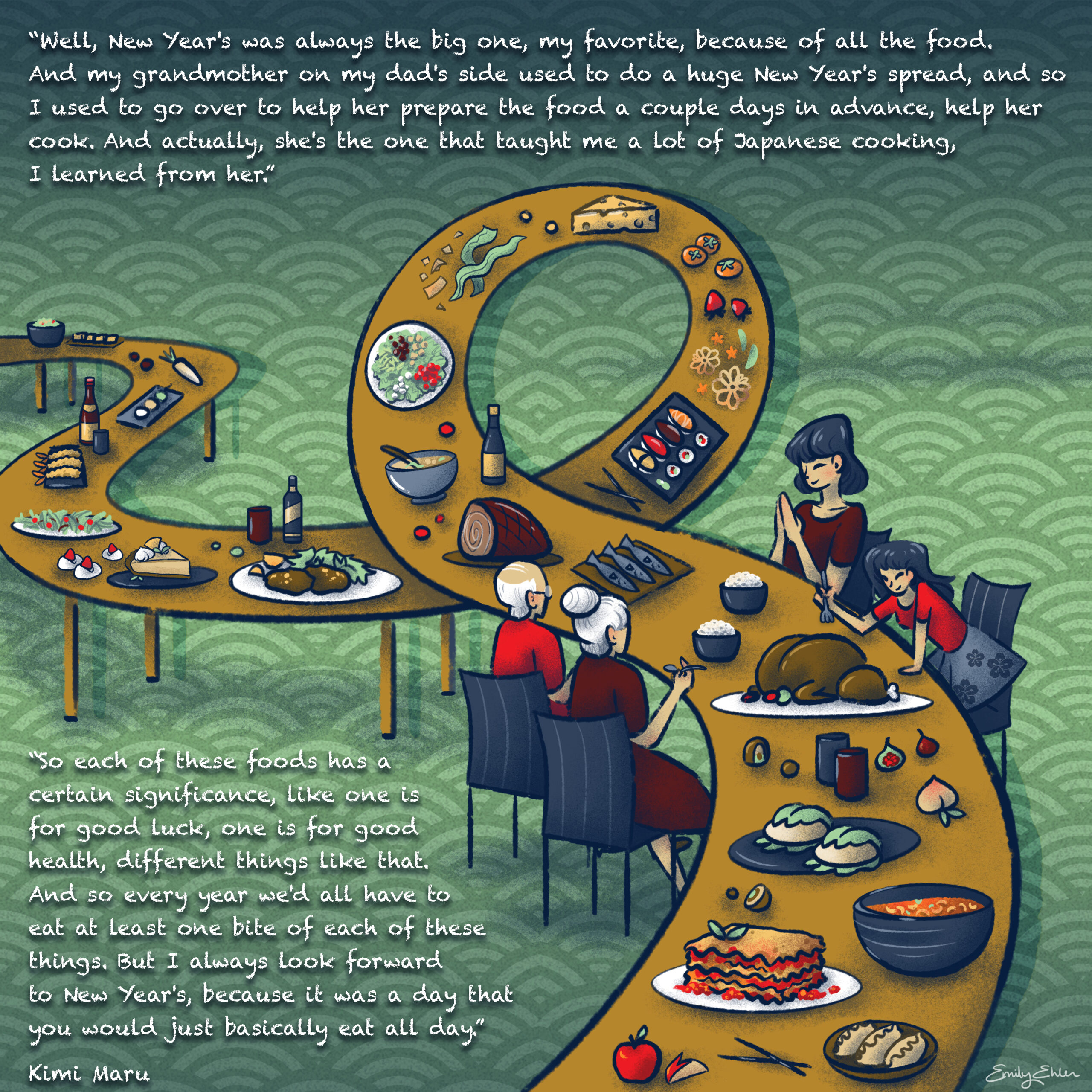

FEAST by Emily Ehlen

This image titled FEAST consists of one panel that depicts a long table that stretches from the left side to the bottom right which loops before reaching four people of different generations eating. The food on the table includes a variety of foods like sushi, lasagna, salad, turkey, and dumplings. Text at the top of the image reads, “‘Well, New Year’s was always the big one, my favorite, because of all the food. And my grandmother on my dad’s side used to do a huge New Year’s spread, and so I used to go over to help her prepare the food a couple days in advance, help her cook. And actually, she’s the one that taught me a lot of Japanese cooking, I learned from her.'” Text on the bottom left of the image reads,, “‘So each of these foods has a certain significance, like one is for good luck, one is for good health, different things like that. And so every year we’d all have to eat at least one bite of each of these things. But I always look forward to New Year’s, because it was a day that you would just basically eat all day.'” Text on the bottom left indicates these quotations are from Kimi Maru’s oral history for the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project.

Explore the oral history interviews in the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project, listen to The Berkeley Remix podcast season “’From Generation to Generation’: The Legacy of Japanese American Incarceration,” and discover related resources on the Oral History Center website.

Acknowledgments for the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project

This project was funded, in part, by a grant from the U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant Program. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government.

This material received federal financial assistance for the preservation and interpretation of U.S. confinement sites where Japanese Americans were detained during World War II. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and the Age Discrimination Act of 1975, as amended, the U.S. Department of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, disability or age in its federally funded assisted projects. If you believe you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility as described above, or if you desire further information, please write to:

Office of Equal Opportunity

National Park Service

1201 Eye Street, NW (2740)

Washington, DC 20005

ABOUT THE ORAL HISTORY CENTER

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. You can find our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

Please consider making a tax-deductible donation to the Oral History Center if you’d like to see more work like this conducted and made freely available online. The Oral History Center is a predominantly self-funded research unit of The Bancroft Library. As such, we must raise the funds to cover the cost of all the work we do, including each oral history. You can give online, or contact us at ohc@berkeley.edu for more information about our funding needs for present and future projects.