(Students examine papyri and ostraca during their class visit. Photo by Lee Anne Titangos.)

Writing History: Undergraduate Research Papers Investigate Ancient Papyri

Leah Packard-Grams, Center for the Tebtunis Papyri

This semester, students enrolled in the writing course “Writing History” (AHMA-R1B) got the chance to work as ancient detectives. As their instructor, I asked them each to write a research paper about one of the various ancient documents held in the Center for the Tebtunis Papyri in The Bancroft Library. After examining their options in a class visit, they each chose a papyrus or ostracon to write about. Students were given modern translations of the papyri and ostraca to read, making the ancient texts accessible.

Students Use Interdisciplinary Approaches

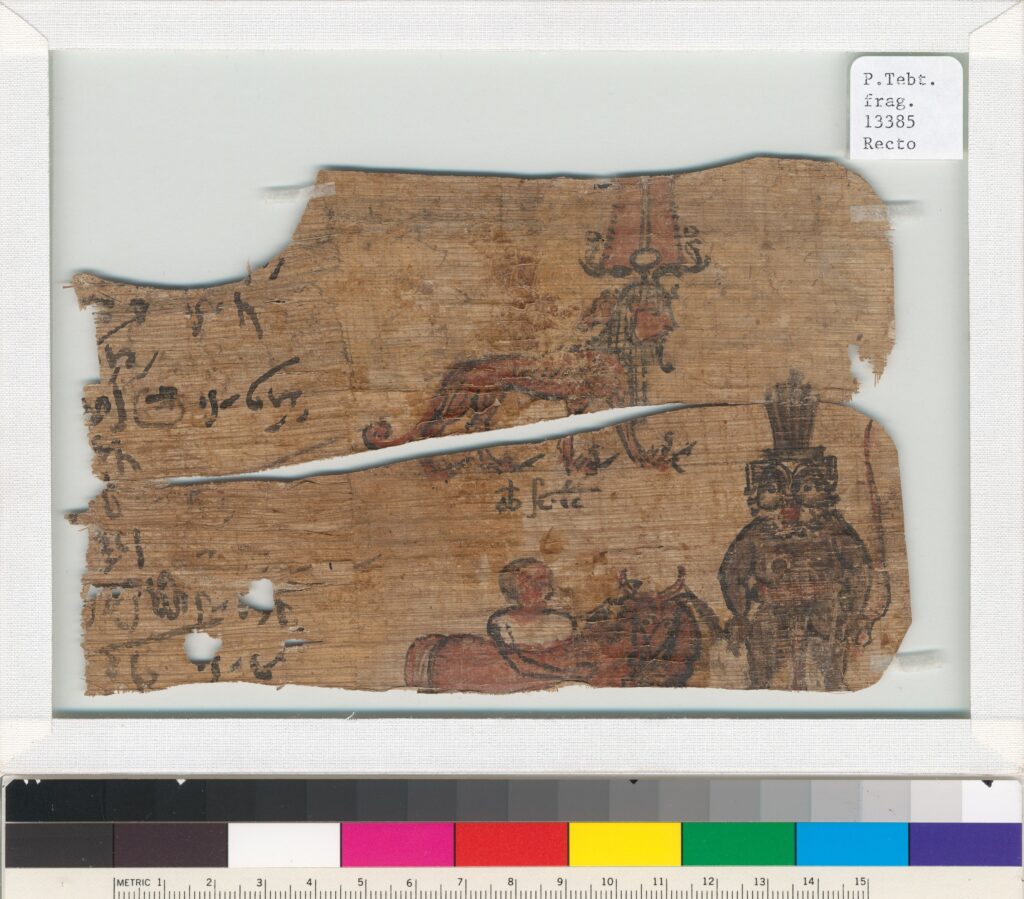

The papyri, ostraca, and artifacts from Tebtunis at UC Berkeley were excavated from the site in 1899-1900, and the material has been an asset for Berkeley’s research and teaching collections for over a century. However, with over 26,000 fragments of papyrus, about two dozen ostraca, and many artifacts in the Hearst Museum, there is still plenty of work to be done! Students noticed new things in these artifacts: senior Chloe Logan, for example, described the painting on the reverse side of an inscribed papyrus for the very first time; it had been ignored by scholars for decades despite several scholarly citations of the text on the other side. P.Tebt.1087 was used as part of mummy cartonnage, a sort of ancient papier-mâché that was painted to decorate the casing of the mummy. Cartonnage was made by gluing together layers of previously-used papyrus and then painting over the gessoed surface. Her paper examines both the painted side of the papyrus as well as the inscribed side. Using an art-historical approach for the painted side and an economic-historical approach to analyze the content of the financial account on the other side, she wrote an interdisciplinary study of the piece that considered both sides of the artifact, and considered this as an example of ancient recycling.

Ian McLendon compared receipts and tags for beer on ostraca in the collection (an ostracon is a broken potsherd reused as a writing surface). His paper examined the ways beer was used in ritual dining in Tebtunis, and compared the types of documents that record the beverage’s use, cost, and delivery. He even examined some ancient coins to see what it would have been like to pay for beer using drachmai and obols, the ancient currency in use in Ptolemaic Egypt.

Mastering Demons

Nicolas Iosifidis was also inspired by an illustration on a papyrus. Tutu, the “master of demons,” was an apotropaic, protective deity in ancient Egypt who defended against forces of chaos who would do harm to humans. In the papyrus, he is depicted as having a human head, a leonine body, and has snakes and knives in his paws– perhaps even in place of his fingers! His headdress and double-plumed crown also contribute to the awe-inspiring effect of this formidable deity. Iosifidis sees Tutu as an opportunity to examine our deeper selves and master our own demons, asking the question, “Is there something else we can acquire from it [the papyrus] as did people back then?” His paper offers an analysis of the exact role of the master of demons, writing that “Tutu doesn’t protect by killing [demons], but rather controlling or taming them.” The god Tutu, for Iosifidis, represents the timeless struggle between “the good and the bad” that exists within us all.

Reading Between the Lines

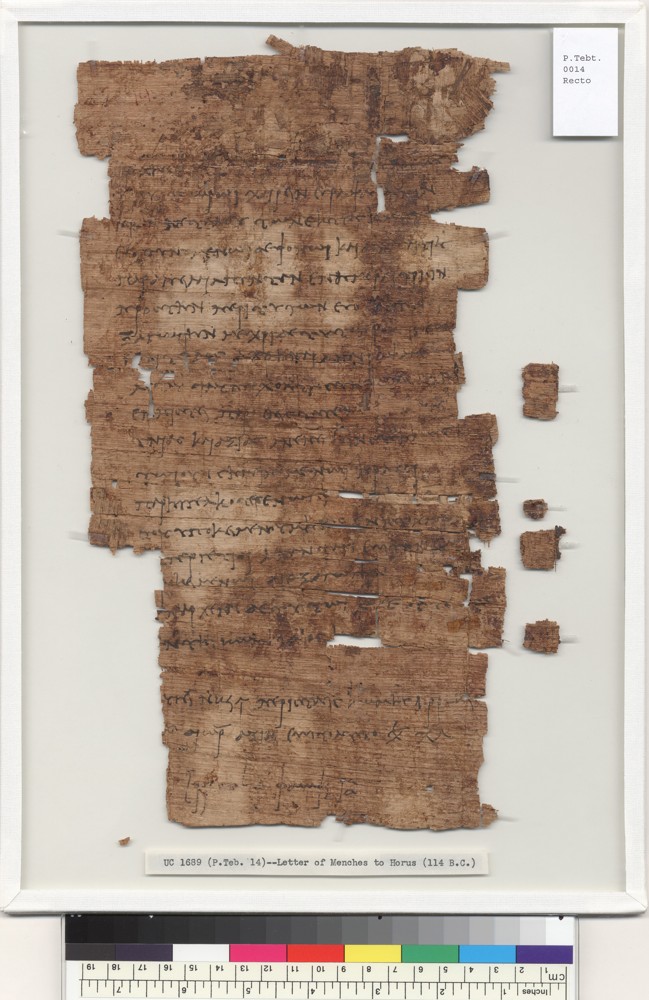

Reading their papers, I was struck in particular by the students’ enthusiastic comments on the significance of these papyri to broader human history. Alex Moyer chose a papyrus that dealt with the investigation into a murder that occurred in 114 BCE, observing that despite the unfortunate universality of homicide throughout human history, “What distinguishes each society from any other is their approach to investigating and handling murders.” His papyrus, P.Tebt. 1.14, is a letter from a village scribe that offers insight into the process of confiscating the property of an accused person until he can be tried and sentenced. Instead of apprehending him, the village scribe was instructed to “arrange for [his property] to be placed on bond” (lines 9-10). Moyer writes about the value of this papyrus as comparative evidence: “Due to the fair condition and legibility of the papyrus, it is able to act as a figurative time capsule, allowing us to compare and contrast with other societies, including our own, and view how human civilization’s attitude and handling of murders have changed over time.”

Victor Flores decided to write about the same papyrus, and was surprised at how this papyrus challenges our perception of the job of an “ancient scribe.” He writes, “These village scribes are not your ordinary scribes, but rather carry a distinct number of tasks like arranging for the bond in order for somebody to confiscate valuables along with carrying out a wide variety of administrative tasks for the government beyond simply writing.” The “village scribe” wasn’t simply a copyist or secretary as one might suppose, and this papyrus is good evidence that allows us to ascertain the roles of scribes!

Student Perspectives

Working with the papyri in The Bancroft Library, I have found that there is a feeling, almost indescribable, when you look at an ancient artifact and really take the time to appreciate what lies before you. Staring up at you is a ghost– a physical echo– that reverberates across the millennia. The artifact before you has survived by sheer luck, and we are fortunate that it remains at all. I tried to convey this to my students, and in their papers, I found that students wanted to write about what it was like to study the papyri up close. This was unprompted by me, and I was astounded at the care and reflection they undertook to share their own perspectives:

Chloe Logan (class of 2024, writing about the cartonnage fragment): “I must remark how fortunate we are to have an incredible artifact in such good condition as a window to the distant past. I hope we will have more research on the verso side of this astonishing relic.” [Indeed, it is being studied by a scholar in Europe for publication soon!]

Ethan Schiffman (class of 2027): “I enjoyed visiting the Bancroft Library and seeing the large Tebtunis Papyrus collection. I can now better appreciate the magnitude of the time-consuming task of the care involved in preserving the fragile papyri and the difficulties in translating and editing these texts.”

John Soejoto (class of 2027): “By exploring each papyrus, even if only a vague or unproven hypothesis is formed, historians increase the existing body of knowledge and give the future academic community further means to discover the history of bygone ages.”

Wilder Brix Burke (class of 2027): “[Seeing the papyrus in person after studying it for so long] brought a new perspective, a real understanding of the physical lengths such a text had gone to simply exist before me, 2000 years (and some change) later. It also speaks to the impressive ability of UC Berkeley as a whole that undergraduate students get to observe the most unique and fascinating parts of campus. I am grateful for the opportunity to see history before my eyes. These are the moments that remind me why I am a CAL student. Go bears!”