Tag: OHC

Notes from the Field: Videography and New Changes in Oral History

by Todd Holmes

As in so many professions, the evolution of technology continues to add new dynamics to the practice of oral history. Indeed, longtime veterans of the field have witnessed this development firsthand, as audio recorders transformed from the reel-to-reel setups which nearly required an entire tabletop, to digital devices that now can neatly fit in the palm of one’s hand. And with these changes came new dynamics in the interview process. Bulky equipment no longer encumbered the space between interviewer and narrator, nor did concerns about power sources, room size, or running out of tape.

Today, video recording has become standard practice for many in the field of oral history—a technological step that The Oral History Center took almost two decades ago. In some respects, the use of video could be seen as taking a step backwards, reintroducing a few of the same burdens in the interview process that developments in audio had solved. Yet on the other hand, video also opened up new realms of opportunity, enabling one to capture and preserve an interview in its totality and place both an audio and visual recording of the conversation into the historical record. And of course, among the many promising uses of such video recordings is a documentary film.

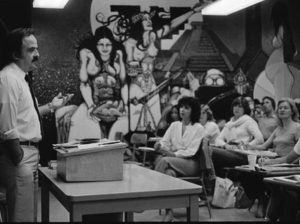

Conducting interviews that will be used in a documentary, however, again ushers new dynamics into the interview process, dynamics I began to experience firsthand. In 2016, I initiated the Chicana/o Studies Oral History Project which sought to document the experience of the first generation of scholars who founded and shaped the academic discipline over the last half century. This past year, we decided to partner with film makers to put those twenty-five interviews into conversation in a documentary, tentatively titled Chicana/o Studies: The Legacy of a Movement and the Forging of a Discipline. Since joining the OHC, I had video recorded scores of interviews, and thus was no stranger to the practice of framing a pretty good shot. I paid attention to lighting, the triangulation of the camera with myself and narrator, and made sure to avoid the cardinal sin of having something in the background seem like it was sprouting out of the narrator’s head. Yet when the prospect of using these recordings in a film became a reality, I quickly realized that I had a responsibility to take much more time and care in the videography. A “pretty decent shot” was no longer good enough to do justice to both the film and the narrators featured in it. I thus began to more closely select the interview space, one that featured the best possible light and, above all, background. In the past I feared inconveniencing my narrators, often settling for a less optimal video shot because it was easier for them. Yet for the film, I now had to become assertive about the recording space. It was no longer out of the ordinary for me to rearrange a corner of someone’s office or living room, and spend 20 minutes or more staging the background using items from around the room, office, or house. In fact, at times I even brought my own staging materials when needed. At first blush, such procedures could be deemed more hassle than benefit—a sentiment I’m sure a fair share narrators likely held. Yet my answer to looks of “is this really necessary” was to reassure them of my simple aim: This is for a film, and I want you to look your very best.

When thinking of best practices for videography, I believe that simple aim stands at the center: To place the narrator in the very best position to represent themselves. Achieving that goal surely takes more time and care than just simply sitting down and pushing record. It requires being assertive about the recording space, taking the time to properly stage that space, and paying attention to the little details that, more times than not, we would all prefer to sidestep. Yet when done correctly, you will have a finished product that does justice to both the overall project and, most importantly, the narrators featured in it.

Oral History Center – From the Archives: Charles H. Warren

Charles H. Warren and California Energy in the “Era of Limits”

Charles H. Warren, “From the California Assembly to the Council on Environmental Quality, 1962-1979: The Evolution of an Environmentalist,” an oral history conducted in 1983 by Sarah Sharp, in Democratic Party Politics and Environmental Issues in California, 1962-1976, Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 1986.

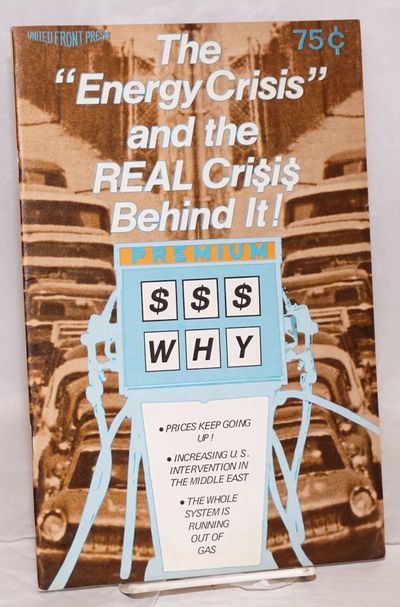

Over the past half-century, California’s electric utility companies have experienced waves of change, challenge, and crisis while producing power and earning profits for their shareholders. Most recently, the San Francisco-based Pacific Gas and Electric Company (PG&E)—one of the largest investor-owned utilities in the United States—began 2019 seeking chapter 11 bankruptcy protections in lieu of deaths and damages from destructive wildfires for which it may be liable. PG&E last declared bankruptcy in 2001 during the California energy crisis under quite different and convoluted circumstances, including the convergence of severe drought, high temperatures, and pricing manipulations derived from poorly designed deregulation of California’s energy markets in the mid-1990s. The energy crisis in the 1970s, however, stands out for its onslaught of economic, environmental, and political overlap, which left many businesses and policy-makers at a loss with how to cope and move forward.

By 1976, fuel shortages and forecasts of rolling blackouts from California’s utilities spurred then Democratic Gubernatorial candidate Jerry Brown to characterize the 1970s as “an era of limits.” From 1962 through that “era of limits,” Charles H. Warren served as a leading Democrat in California’s Assembly. Warren’s legislative response to California’s energy issues in the 1970s gained national recognition and led him, in 1977, to join President Jimmy Carter’s cabinet as chair of the Council on Environmental Quality. Warren addresses all this in his oral history interview, recorded in the early 1980s. Amid new energy challenges facing California’s utilities today, revisiting Warren’s oral history reveals how one legislator in California’s Assembly confronted the 1970s energy crisis, sometimes supporting and other times challenging California’s powerful utility companies.

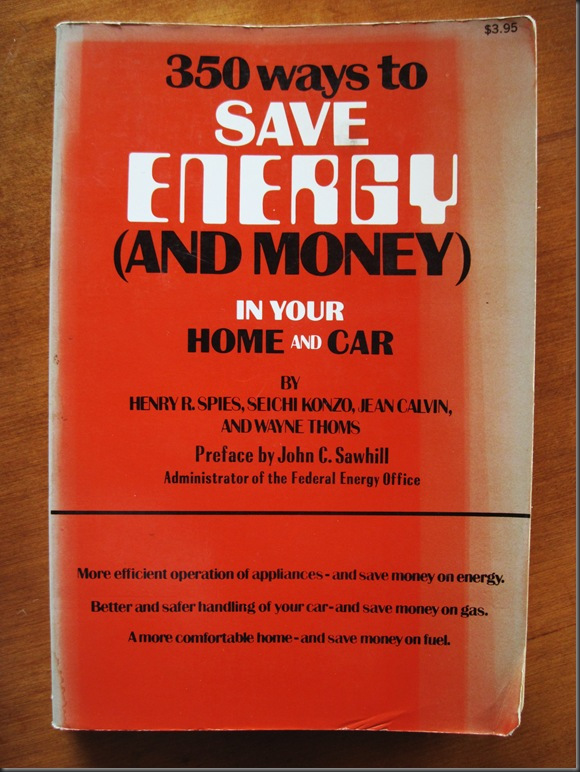

Most memories of energy in the “era of limits” trace back to October 1973 when Saudi Arabia and other Arab nations in OPEC—the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries—halted exports of crude oil to the United States and its allies. Arab members of OPEC initiated their embargo as punishment for American military support of Israel after Syria and Egypt launched a surprise attack against the the Jewish state on Yom Kippur. OPEC’s oil embargo lasted only from October 1973 through the spring of 1974, but it sent shock waves throughout the industrialized world. For one, the price of oil suddenly quadrupled. The U.S. economy contracted, throwing millions of Americans out of work, while those who kept their jobs saw minuscule progress on wages. As a member of California’s assembly, Charlie Warren played an outsized role in drafting California’s legislative and regulatory responses to the 1970s energy crisis. Yet in his 1983 oral history interview, Warren explained how California’s utilities expected critical energy shortages much sooner than you might expect.

A few years before the OPEC oil embargo, California’s electric utility companies warned state legislators of a separate impending energy crisis. Warren recalled, “during 1971, the major electric utilities in California, PG&E, Southern California Edison, and San Diego Gas and Electric, advised legislative leaders that unless the state took certain action, in the foreseeable future there would be shortages of electricity with resulting brownouts and blackouts of indefinite duration.” The problem, according to the utilities, was that regional and local governments in California made it increasingly difficult to site new and necessary power stations, particularly new nuclear plants fueled by uranium. In response, the utilities succeeded in passing legislation through the California Senate that would preempt the jurisdiction of local governments and regional agencies for siting new power stations. In the Assembly, that legislation came to the Planning and Land Use Committee on which Charlie Warren served. Warren and fellow committee-members feared the utilities’ energy forecasts but felt reluctant to approve legislation that removed local control for locating power plants and put it the hands of a new state agency, as requested by California’s utilities. The committee decided the issue required deeper investigation.

Warren found himself chairing a new subcommittee on energy that contracted with the Rand Corporation in Santa Monica to evaluate California’s electrical energy system and the utilities’ anticipated crisis. The Rand Corporation had, until that time, exclusive contracts with the U.S. military for complex systems analyses, especially scenarios involving global nuclear war. Yet Rand began expanding their research into the non-military policy area, and this contract with California’s state government afforded an early opportunities to do so. Warren’s subcommittee received the Rand report in October 1972, and as he recalled, “I was so startled by its findings that my life was changed.” Warren’s responses to this report reshaped regulation of California’s energy landscape and catapulted him to national attention as a legislative expert on energy issues.

The Rand report substantiated the utilities’ anticipated energy crisis. According to Rand’s analysis, California’s annual demand for energy was growing so rapidly—and was forecast to expand at similar rates over the next twenty years—that avoiding projected blackouts would require all of California’s then-existent electricity production to double every ten years. That is, the entire capacity of California’s electric output would need to completely replace itself every decade, all while maintaining its existing output. To make matters worse, the Rand report also noted how the traditional means of generating electricity with natural gas and low-sulfur crude oil were becoming increasingly scarce and more expensive (even before the OPEC embargo restricted the availability of crude oil and quadrupled its price!) Rand further reported that, in response to these anticipated challenges, California’s utilities planned to generate this additional energy with scores of new nuclear power plants. The utilities projected that, by the year 2000, an additional one hundred large power plants would be required throughout California, at least eighty of which they imagined would run on nuclear fuel.

Before deregulation of California’s energy markets in the 1990s, utilities operated as profitable, state-sanctioned monopolies. For California’s investor-owned utilities like PG&E and SoCal Edison, a surge of newly constructed power plants would not just meet the state’s rapidly growing energy needs, it would substantially boost the utilities’ bottom line. At the time, most Americans had limited knowledge or concern about nuclear energy. Indeed, most Americans in the early 1970s still believed nuclear power would provide energy too cheap to meter and do so without significant consequences. However, the Rand report expressed considerable apprehensions both about nuclear generator technologies and reliance on nuclear energy to the extent California utilities thought necessary.

In the spring of 1973, Warren initiated a series of California Assembly hearings on the findings in the Rand report. The hearings, Warren recalled, “were lengthy, time consuming, and adversarial.” But as a result, Warren learned a great deal on the deep economic, environmental, and political complexities involved in energy production and use. Among other things, Warren realized “it would be imprudent to rely on nuclear to the extent the utilities then planned.” Rather than endlessly construct new nuclear stations or build new power plants that ran on dirty and increasingly expensive fuels, Warren imagined a program of increased efficiency through energy conservation and efforts for alternative energy. Warren also realized, however, that the combined influence of California’s utilities and the public’s limited knowledge on nuclear issues made it “politically impossible to make a case against nuclear in order to justify a program of energy conservation and energy alternatives development.”

Instead, Warren drafted new legislation for substantial changes to state energy policies that, without mentioning nuclear power, relied on significant land use and water requirements for the siting and operating of new power plants. Overcoming his initial hesitations for a new state entity, Warren’s legislation proposed a new energy agency that would adopt conservation measures in all electricity consuming sectors; it would encourage the development of alternative energy resources, specifically solar and geothermal; and it would conduct independent energy forecasts for electricity similar to what the Rand report did. After some additional amendments, Warren’s legislation passed both the California Assembly and Senate.

By early Autumn in 1973, Warren’s legislation arrived on the desk of California Governor Ronald Reagan, who vetoed the bill. Within a few weeks, however, the OPEC oil embargo suddenly made energy a serious political concern. Reagan’s staff realized Warren’s bill had merit and regretted its hasty veto. The governor’s office soon contacted Warren to create a new policy together that would confront the energy crisis—a crisis that California’s utilities had in some ways anticipated. Over a period of several weeks, Warren began “extended negotiations with the governor’s staff, and with the governor personally,” as well as intense meetings with utility representatives, legislative staff, and state agency officials. Together, they produced what became known as the Warren-Alquist State Energy Resources Conservation and Development Act, or Assembly Bill 1575, which was markedly similar to Warren’s earlier bill that Reagan first vetoed.

California’s utilities disliked AB1575, but they supported it at Reagan’s insistence. “The governor’s support,” Warren remembered, “was at some political cost to himself. I recall a staff person who had been given responsibility for energy policy resigned and Lieutenant Governor Ed Reinecke who was campaigning for governor publicly announced his opposition. But Reagan kept his word.” With the governor’s aid, AB1575 moved through California’s Assembly and, by a margin of one vote, it found approval Senate in 1974. This time Reagan signed it, marking the nation’s first substantial legislative effort to confront the 1970s energy crisis—not through inefficient if profitable new power plants for utility monopolies, but through energy conservation, increased analyses, and pursuit of alternative energy sources.

The enactment of the Warren-Alquist Act in 1974 strengthened California’s leadership in the management and production of power. Among other things, the bill created the California Energy Commission, formally the Energy Resources Conservation and Development Commission, which remains California’s primary energy policy and planning agency. It set forth state policies concerning the generation, transmission, and consumption of electrical energy and established a comprehensive administrative procedure for review, evaluation, and certification of power plant sites proposed to meet forecasted power demands. According to Warren, the bill was also “the first to challenge the policies of energy inefficiency of the utilities and to point out that energy planning by the utilities was devoted more to maximizing profits than to the public’s interest in a rational and reasonable energy program. It did this by establishing a state energy agency [the California Energy Commission] responsible for energy demand by forecasting, energy conservation and efficiency standards, development of alternative energy supply systems, and simplifying and shortening the process for siting power plants.”

Charles Warren’s oral history continues to outline his additional experiences drafting formative policies in the 1970s that reordered the ways utility producers and energy-consumers conduct business and use resources in California. In 1975, Warren helped draft the Utilities Lifeline Act, by which each residential user of electricity and gas in California would receive a minimal supply of energy at a discounted price but would pay a higher price for energy taken in excess of that minimum. In 1976, Warren drafted the Nuclear Safeguards Act, which still prohibits new nuclear plants from being built in California until the federal government establishes a permanent storage for high-level radioactive waste. Also in 1976, Warren drafted the California Coastal Act, which made permanent the California Coastal Commission’s mandate to enhance public access to the shoreline, protect coastal natural resources, and balance both development and conservation. Today, as California’s utilities struggle to adapt to climate change and to increasingly dynamic markets for energy production, reading Warren’s oral history unveils how one California legislator sought expansive solutions to energy issues and resource challenges during the 1970s “era of limits.”

by Roger Eardley-Pryor, PhD

Oral History Center of the Bancroft Library

Charles H. Warren, “From the California Assembly to the Council on Environmental Quality, 1962-1979: The Evolution of an Environmentalist,” an oral history conducted in 1983 by Sarah Sharp, in Democratic Party Politics and Environmental Issues in California, 1962-1976, Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 1986.

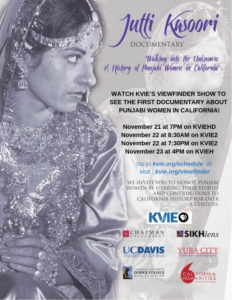

Cal Alum Makes PBS documentary on California’s Punjabi Community

OHC Advanced Oral History Alum Spotlight: A Q&A with Nicole Ranganath

Cal alum Nicole Ranganath’s documentary on California’s Punjabi community recently premiered on PBS. Currently an Assistant Adjunct Professor of Middle East/South Asia Studies at UC Davis, Ranganath joined the Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library at our annual Advanced Oral History Summer Institute in 2015. She was working on a project about women in California’s Punjabi community, and looking to deepen her interviewing skills. Since then, her project grew into a documentary film, Walking into the Unknown, which features 24 life stories of women from this community. We caught up with her to discuss her use of oral history, the film, working with students on the interviews, and why the time was right to do this project.

Q: You joined us in 2015 for the Advanced Oral History Summer Institute. What initially brought you to the Summer Institute?

Raganath: As a Cal alum who worked at Bancroft library as an undergrad, I was already familiar with the great work at the Oral History Center. When I started planning my ambitious project documenting the history of California’s Punjabi community, I found the Summer Institute online and signed up!

Q: You were working on an oral history project about women in California’s Punjabi community. Tell us a little bit about the project.

Raganath: This is the first documentary that focuses exclusively on the untold stories of women in the Punjabi American community of northern California over the last 110 years. Walking into the Unknown features interviews with Punjabi women from diverse backgrounds about their lives, including growing up in India, marriage and family, journeys to the US, and their professional careers. Their extensive contributions to the Punjabi American community and the broader American society have remained invisible. The women also offer compelling eyewitness accounts of major historical events, such as the 1947 Partition, in which over 14 million people were displaced and over one million murdered in religious violence. The project is funded by a grant from the California Humanities, as well as support from UC Davis, Sikhlens and the Punjabi-American community.

What made the project even more poignant is that there was a very narrow window of time in which we could give women a platform for sharing their life experiences. In December 2017, we completed 24 life history interviews on film in Yuba City, Sacramento, Davis, San Francisco, Fremont, and San Jose in just SIX DAYS! Over the last year, the health of three of the elderly ladies was declined so rapidly that they would no longer be able to be interviewed, and sadly one woman passed just away last month.

Q: What did you learn at the Summer Institute that helped you develop the project?

Raganath: The Summer Institute offered a holistic approach to thinking through and planning every aspect of my oral history research. Two aspects of the SI stood out — [OHC Director] Martin Meeker’s help thinking through the agreement process between UC Davis and the partner community organizations, and brainstorming with other participants about their projects. I learned so much from my colleagues.

Q: The project grew into a documentary, Walking Into the Unknown, which features in-depth life stories of 24 women that were interviewed. What was it like to turn these interviews into a film?

Raganath: When I embarked on the oral history research, I didn’t initially intend to create a documentary. With the tremendous support of Sikhlens and the Punjabi community, I got the courage to try to create a documentary film. I’m partnering with the UC History/Social Science Project to integrate the film into K-12 classrooms throughout the state. I encourage other oral history researchers to harness the power of the film medium to share these compelling stories with the general public. I’m very passionate about informing the general public about the Punjabi community’s presence in our state since the 1890s. Most people think South Asians arrived recently in California since the 1970s, but this vibrant community helped build our agriculture, our economy, our railroads, and have contributed to every aspect of our public life. For instance, Dalip Singh Saund was the first Asian American, the first Indian American, and the first Punjabi Sikh to be elected to the US Congress (1956).

Q: How did you adapt the interviews for film?

Raganath: One of the greatest pleasures of this project was creating a summer seminar with 10 students (mostly female Punjabi undergraduates at UC Davis), but also a masters student and a high school student. The students helped translate and transcribe the interviews and within one month they created 800 pages of single-spaced transcriptions of the interviews. We also met each week during the summer to discuss our responses to the often highly emotional interviews with the women. The student feedback greatly influenced my editing process. I was very concerned with capturing the diverse experiences of older pioneer women while also engaging young people to take interest in this history. Editing all of the footage to a short program that is 26 minutes and 43 seconds was not easy! I also greatly benefited from feedback from the other Punjabi women on the planning team who grew up in Yuba City and who were the daughters of some of the pioneer women interviewed in the film — Raji Tumber, Sharon Singh, and Davinder Deol. In short, the editing experience wasn’t easy but the community collaboration and engaging students in the process really helped. The editing team at Sikhlens, especially Hansjeet Duggal, was wonderful to work with as well. The KVIE team also provided invaluable feedback, including Michael Sanford, David Hosley and Alice Yu.

Q: The film premiered at Sikhlens Film Festival in LA in November. What was the reception? Did any of the audience members discuss the use of oral history?

Raganath: The reception at the Sikhlens Film Festival was incredibly positive. Nearly 40 community members, including one of the key pioneer women (Mrs Harbhajan Kaur Takher) attended the premiere. I brought the women involved in the project on stage to honor them. Mrs Takher received a standing ovation.

On November 21, 2018, Walking into the Unknown was broadcast on our local PBS station, KVIE, on their Viewfinder show. You can watch it at kvie.org/viewfinder. The program will rebroadcast on KVIE in April and will be uplinked to other PBS stations nationally later this year. There will be a community screening at the Yuba City Sikh Temple on Sunday, March 17 at 2 pm on Tierra Buena Road. The film will also be screened at the UC Davis South Asia Film Festival on Saturday, May 4 at the International House in Davis. It was very touching to see these courageous women get publicly acknowledged.

Q: What’s next for you? How do you hope to continue using oral history in your work?

Raganath: For this project, I’m finishing part two. We’re in the middle of creating a “women’s gallery” on the existing UC Davis Pioneering Punjabis Digital Archive (pioneeringpunjabis.ucdavis.edu). These women’s stories, including video and audio clips, will be ready by June 2019 for anyone in the world to watch and enjoy. I’m also submitting an article about this project for publication. After that, I’m continuing my oral history work on a book about Sikhs who served in the British colonial administration in Punjab, Fiji, and Africa but then later settled in Yuba City, CA.

The Oral History Center Year in Review: Our Favorite Interview Moments

The Oral History Center has had a productive year, and interviewed many people. Here’s some of our favorite moments from our 2018 interviews. We hope you enjoy them as much as we did!

Martin Meeker:

Of the dozens of revelatory, challenging, or even hilarious moments in my interviews this year, I find it difficult to highlight just one. But I keep coming back to this moment in my interview with famed ACLU attorney Marshall Krause. Krause defended a number of individuals charged with obscenity in San Francisco in the 1960s, including Vorpal Gallery owner Muldoon Elder for putting Ron Boise’s erotic Kama Sutra sculptures on display. While recounting the story, Krause mentioned that he had one of the artworks in question, so I asked him to bring it out to show on camera. I then asked him to provide the kind of defense he did in the courtroom in 1964. Krause’s sensitive, insightful, convincing words made it obvious why the jury acquitted Elder of the charges, thus giving Krause and the cause of the freedom of expression a victory.

Amanda Tewes:

My favorite interview moment of 2018 occurred when I interviewed Bay Area herbalist and aromatherapist Jeanne Rose. In the 1960s, Rose was the couturier for bands like Jefferson Airplane and was very plugged into the local rock and roll scene. During one of our sessions together, Rose recounted her experience at the Altamont Speedway Free Festival on December 6, 1969, when an agitated audience of about 300,000 erupted into violence. Rose watched the chaos from above the crowd, but still recalls the strong emotions from that day. Hearing about the event firsthand reinforced how scary and chaotic the events must have been for concert goers. Interestingly, Rose marked this concert as “the end” of rock and roll.

Paul Burnett:

had started an underground called the Werewolves. We spent quite a bit of

time on that for the first few months. I don’t think we ever found any. We

once raided an outfit that were presumably Werewolves. I don’t remember

what happened to them, except that we sort of used movie techniques to make

the raid, coming through the skylights.

Todd Holmes:

My favorite moment this year was interviewing Professor James C. Scott at his farm in Durham, Connecticut. The Sterling Professor of Political Science and Anthropology at Yale University, Scott is widely regarded as one of the most influential thinkers of our time, producing an unparalleled corpus of books over the last 50 years on peasant politics, resistance, and state governance, which today are standard reading across a host of disciplines worldwide. Yet in the interviews, we get a glimpse of the unassuming human being behind the books as Scott discusses the two principles that have always underpinned his approach to academic work – principles he stresses . The first: “Don’t ever be afraid to be an army of one in a crowd of a hundred,” a philosophy of independence he came to embrace during his Quaker education as a young man. The second: “If you’re not having fun, what the hell are you doing?” For those who know Jim Scott, the latter is certainly an oft-quoted remark he has extolled to colleagues and graduate students for decades. Spending the weekend at his farm, I quickly realized that those principles were not just lofty ideals, but words he lived by, and I would be wise to do the same.

Shanna Farrell:

My favorite moment this year was during an interview with WWII Veteran Lawson Sakai, who is in his nineties, for the East Bay Regional Park Parkland Oral History Project. Sakai’s parent immigrated from Japan, making him Nisei, or second generation. He spoke about needing to flee California to avoid internment, and the role that farming in the Central Valley played to rebuild the Japanese community in the aftermath. Driscoll Farms was just getting started and needed help growing strawberries. They recruited Japanese farmers, asked them to farm the land, and split profits with them 50/50. After hearing how Driscoll helped many people get back on their feet after losing everything in the wake of Executive Order 9066, I scoured my food history books and didn’t find any information about this. I felt like I had stumbled upon a hidden historical gem.

Roger Eardley-Pryor:

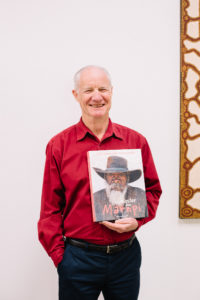

Interviewing Aaron Mair—the 57th president of the Sierra Club and the Club’s first African-American president—provided my favorite interview moments this year. We conducted Aaron’s initial interview session at the Hagood Mill Historic Site in the upcountry of South Carolina. As his family’s genealogist, Aaron has the 1865 records of his enslaved great, great grandfather Zion McKenzie’s emancipation from the Hagood family. Before interviewing at the Hagood Mill site, Aaron and I visited the humble, un-fenced cemetery of his enslaved ancestors, whose rough, uncut gravestones lay just outside the Hagood family’s iron-fenced grave site with grandiose tombs and Confederate soldier crosses. Later, during his interview, Aaron recounted his ancestors’ remarkable stories from slavery to freedom and their purchase of farm land that remains in Aaron’s family today. His family’s narrative, from human dominion to sustainable stewardship of land, informs Aaron’s ideas on environmental responsibility. And it helped inspire Aaron’s initiatives as Sierra Club president to unify activism for environmental rights with civil rights and labor rights. Aaron takes seriously Sierra Club founder John Muir’s admonition that “When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe.”

Mair and Eardley-Pryor

OHC Commences Project to Commemorate 50th Anniversary of Chicana/o Studies

by Todd Holmes

Today, courses on the Mexican American experience can be found at nearly every college campus across the nation. In an academic environment long entrenched within the mold of Western Europe, such curriculum is nothing short of a miraculous testament to the diversification of American education. Indeed, the subject has its own journals, national organizations, student groups, academic departments, and specialized degrees. Yet fifty years ago, the discipline of Chicana/o Studies—as the field of study became known—was just taking shape and, above all, struggling for legitimacy.

To commemorate the 50th anniversary of the discipline, the OHC initiated the Chicana/o Studies Oral History Project. Led by Todd Holmes, the project documents the historical development of the field through in-depth interviews with the first generation of scholars who shaped it. Holmes began working on the project in the fall of 2016 with the initial step of putting together an advisory council composed of Chicana/o scholars from around the country. Based on the council’s recommendations, over 25 prominent scholars were selected to be interviewed—scholars whose pioneering research and innovative work played a significant role in building the discipline over the last five decades. Holmes then commenced an ambitious fundraising campaign, going directly to the home universities of the featured scholars. To date, the project has received generous support from a host of academic institutions, including the University of California Office of the President, California State University Office of the Chancellor, Stanford University, Arizona State University, and the University of Texas at Austin.

The interviews will offer an important look at the formation of Chicana/o Studies, as well as the experiences of those who built it. Such areas of discussion include their family background, undergraduate and graduate experiences, and academic career as faculty members. With most—if not all—of these scholars standing as the first in the families to attend college, and certainly among the first cohort of Mexican American graduate students and faculty, their experiences highlight the evolution of the field, the diversification of higher education, and the long struggle that underpinned both. Moreover, the interviews trace significant shifts within the field of Chicana/o Studies over the decades, and how the field expanded from college campuses in California and Texas to a nationally recognized discipline of study.

All interviews are slated to be completed by the summer of 2019. When done, they will be featured on a dedicated page of the Center’s website. Moreover, the oral histories will form the heart of a documentary film, tentatively titled, Chicana/o Studies: The Legacy of A Movement and the Forging of A Discipline. The OHC is thrilled to make this foray into film and collaborate with veteran producer Ray Telles and others in this exciting effort. Stay tuned for further updates in 2019!

First Generation Scholars

Norma Alarcón (UC Berkeley)

Tomás Almaguer (San Francisco State)

Rudy Acuňa (CSU Northridge)

Mario Barrera (UC Berkeley)

Albert Camarillo (Stanford)

Martha Cotera (UT Austin)

Antonia Castaňeda (St. Mary’s College)

Edward Escobar (Arizona State)

Juan Gómez-Quiňones (UCLA)

Mario T. García (UC Santa Barbara)

Deena González (Loyola Marymount)

Richard Griswold Castillo (San Diego State)

Ramón Guitierrez (University of Chicago)

José E. Limón (UT Austin)

David Montejano (UC Berkeley)

Emma Pérez (University of Arizona)

Ricardo Romo (UT San Antonio)

Raquel Rubio-Goldsmith (University of Arizona)

Vicki Ruiz (UC Irvine)

Ramón Saldivar (Stanford)

Rita Sanchez (San Diego State)

Rosaura Sánchez (UC San Diego)

Carlos Vélez-Ibáňez (Arizona State)

Emilio Zamora (UT Austin)

Patricia Zavella (UC Santa Cruz)

For more information on the project, its participants, and to view the film’s trailer, visit the project page..

OHC Advanced Oral History Summer Institute Alumni Spotlight: Alec O’Halloran

We recently caught up with one of our Advanced Oral History Summer Institute alums, Alec O’Halloran, who recently published a book that was influenced by his work with us. His book, The Master from Marnpi, is based on oral history interviews. O’Halloran reflects on his work, his time with us, and the release on his book.

(Applications are open now for the 2019 Summer Institute from August 5-9. Apply now!)

Q: How did you first come to oral history?

I don’t have a ‘first’ recollection. I’ve always been interested in stories and in the 1990s (in my forties) I was drawn to the larger story of Aboriginal art and history in Australia, which I knew very little about. This led to reading autobiographies and biographies of Indigenous people, as well as attending art exhibitions etc. Oral history interviews were often quoted in stories about Aboriginal artists, particularly older people from remote parts of Australia that most of our population knew very little about.

When I began researching the life of an artist whose work I admired, Mick Namarari Tjapaltjarri, I found out he had done two recorded interviews in his language, Pintupi, a decade before he passed away (1998). I found those interviews – or their translated transcriptions – fascinating! What a life he had led… so different to mine. Those interviews motivated me to look around for more oral history work that engaged with Aboriginal artists in particular.

Q: Tell us a little bit about the project you were working on when you attended the Advanced Oral History Summer Institute.

I attended the Institute in 2010, in part with support of a travel grant from my institution, The Australian National University in Canberra, where I was undertaking a doctoral program in Interdisciplinary Studies. My thesis project was the life and art of Mick Namarari Tjapaltjarri. I had a rough draft of his life story by that stage, and I was mostly preoccupied with assembling the chronology of events, rather than comprehending his character.

Q: How did your work benefit from the Summer Institute?

One thing I still remember from one of the guest lecturers was about ‘listening and hearing’ when working with recorded interviews. And with so many conversations with fellow participants about each other’s projects, I realised I was not fully engaging with the materials I had at hand. So, I when I returned home to Sydney I took a more rigorous approach.

I went back to the original recordings of Namarari (one audio, one video), and the transcripts, and tasked myself to see and hear more than I had before. To not only track events and incidents and the chronology of his life story, but to look beneath and between the lines and sounds for character and personality traits, for nuanced references to culture, to allusions to relationships with other people. I said to myself, ‘These two interviews are like gold, I need to use them to the fullest’. So the Institute motivated me to be much more dedicated to the oral history component of the biographical research about Namarari’s life and art. This certainly improved the quality of my writing when I was integrating Namarari’s voice into a wider story that involved multiple voices and archival sources.

Another outcome too. Oral history as a data-making history-creating method became more important to me. I don’t think I was an expert practitioner, so I tried to improve the quality of my interviewing work. This involved better planning of interviews and better conduct as the interviewer. Also, I saw that I had an opportunity to contribute to the field in a meaningful way.

The region where Namarari lived is called the Western Desert. It occupies a vast swathe of Central Australia. (Bigger than Texas!) My field work took me to that region, first by air to Alice Springs, and then by four-wheel drive (essential for the outback gravel roads). I realised I could do additional oral history work outside my specific research project as part of my travels. During 2011-13 I was awarded two oral history grants by the Northern Territory Government, which I applied to producing two community oral history reports: for the desert communities of Mount Liebig and Kintore. I interviewed some twenty Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people and submitted a report, and deposited the interviews with the Northern Territory Archives Service in Darwin. I hope that one day a community member or researcher will come along who wants to write a local history of those places and find those interviews… they can then serve a good purpose. Importantly, but sadly, some of the people I interviewed have passed away.

Q: What’s the status of your project now?

My project, to produce an authorised biography on the life and art career of Mick Namarari Tjapaltjarri, is complete! The master from Marnpi was released on 7 September 2018.

See my website for more information www.alecohalloran.com

Q: How did your biography, The Master from Marnpi, benefit from the use of oral history?

Namarari passed away in 1998, before I started my research, so I never met him and I could not interview him. This contrasts sharply with the majority of Aboriginal artist’s biographies in recent decades in Australia – they are invariably deep collaborations between the author and subject.

My narration of Namarari’s life story is based on his testimony: two interviews recorded in Pintupi, in 1989 and 1992, each conducted in the Western Desert by non-Aboriginal researchers who had travelled there for that purpose (and to interview other Aboriginal people of the area).

Thus it is his (translated and transcribed) voice that runs through the chapters. The many gaps are filled, where possible, with other oral history interviews I did with his relatives, and with art advisers who worked with him across his art career (1971-1998). I also drew on other oral histories, both my original interviews and from the archives, to enrich the narrative, applying more details to local histories of place, and shining a light on prevailing attitudes and circumstances that Namarari and his Aboriginal countrymen found themselves in. Where possible, I added salient photographs from a wide range of archives to illustrate what was referred to in the text by people who were ‘there at the time’.

Q: You have some visual components in the book, like maps. How did you weave visual elements with oral history?

The non-text items are: maps (of Australia, and the Western Desert region where Namarari lived), diagrams (eg, the Aboriginal kinship system), tables (eg, Namarari’s annual art output from 1971 to 1998), photographs of people, places (eg, desert scenes, Namarari’s house), and art (primarily his paintings).

The visual components serve to show the reader something of what the story-teller (eg, Namarari or his relatives) was talking about. If it was an important water-source location from his childhood in the 1930s, I would include a photograph. If it was a settlement where he lived in the 1950s, I would look for appropriate pictures from that era. Unsurprisingly there are many more useful photographs from the 1990s than the 1950s.

I applied a policy of sorts to the inclusion of images: it had to illuminate something in the text, rather than being a decorative piece to fill a space. I sometimes juxtaposed images to make a point, such as two artworks that had a subtle feature in common.

Q: What kind of projects do you draw inspiration from?

I have really been preoccupied with my book for several years, so I haven’t been looking for extra inspiration. When I was doing the biographical research I drew inspiration (and understanding) from reading Indigenous autobiographies… they often had the raw truth of historical circumstance from the mouths of those who experienced events and situations and policies.

Women in Politics Panel Discussion with Jane Kim and Mary Hughes Event Recap

By Amanda Tewes, OHC interviewer

In last month’s midterms elections, a wave of diverse women swept into political office across America. From local school boards to Congressional and gubernatorial races, women showed up this November. While many may point to this result as the culmination of women’s dedicated activism since 2016, in places like the Bay Area, well-established political organization helped pull women candidates over the finish line.

On Tuesday, November 13th, one week after the polls closed, OHC staff and local political buffs met at The Ruby to discuss the historical and contemporary role of political women in the Bay Area and to help kick off the Women in Bay Area Politics Oral History Project. The event featured a panel discussion with political consultant and Close the Gap California founder Mary Hughes and San Francisco Supervisor Jane Kim. From their combined years of experience, Hughes and Kim shared insight into what it’s like being a woman in Bay Area politics.

One great question from the audience asked the panelists about how women balance family obligations and political careers. Hughes recalled overhearing a recent conversation in which a woman was praised for waiting to run for office until her children were older. Hughes was dismayed to realize these double standards still existed for women in 2018, and noted that men do not face similar criticism. Similarly, Kim explained that her office is full of working mothers, and that while this was a challenge to balance at first, it also has helped productivity during normal work hours.

Hughes also reminded the audience that while women’s campaign successes are nearly on par with that of men, the struggle often occurs when trying to convince women to run for office in the first place. Even when they are extremely qualified, some women need to be asked more than once. Hughes praised Kim for continuing to run and participate in politics, even after setbacks. She explained that dusting yourself off and trying again is important in order to push toward gender equality in political office.

The stories Hughes and Kim shared reinforced the need to document the histories of Bay Area political women in order to get a clearer picture of the breadth of political work women have been doing on the ground and behind the scenes. Now is the time to undertake this endeavor to celebrate and learn from Bay Area women who have shaped local and national politics.

Please help us out by suggesting women narrators whose political work has been unsung! Which stories about women in politics aren’t making it into the historical record?

To support the Bay Area Women in Politics Project, visit ucblib.link/givetoOHC. Please note under special instructions: “For the Bay Area Women in Politics Oral History Project.”

If you would like to learn more about the project, please contact Amanda Tewes at atewes@berkeley.edu.

From the Archives: Staff Picks

This month, we’re bringing you a special edition of our From the Archives department. Below are interviews, all available in the OHC archives, recommended by each of us. Enjoy digging through the crates!

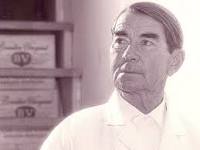

Martin Meeker’s pick:

Andre Tchelistcheff: Grapes, Wine, and Technology. Some lives in our collection of interviews are just profoundly interesting, and well worth digging into. This might be because of difficulties surmounted, achievements recognized, or simply the quality of the telling. Our 1979 oral history with Andre Tchelistcheff reveals one such life that ticks all of those boxes. From his birth in Russia in 1901, through his harrowing escape during the Revolution, to his years in France studying viticulture, and his decades quite literally remaking California’s wine industry, Tchelistcheff lived a remarkably influential life while remaining rooted in his passions throughout.

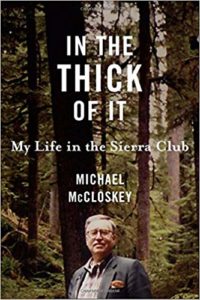

Roger Eardley-Pryor’s pick:

J. Michael McCloskey (Mike McCloskey), “Sierra Club Executive Director and Chairman, 1980s-1990s: A Perspective on Transitions in the Club and the Environmental Movement,” conducted in 1998 and published in 1999, is the second oral history with Mike McCloskey as part of the Sierra Club Oral History Project. Mike, a longtime leader in one of the largest environmental organizations in the United States, discusses the Club’s growing pains associated with an upsurge in membership amid Ronald Reagan’s anti-environmental actions in the early 1980s. Today, in lieu of modern assaults against environmental protections, Mike’s oral history sheds light on ways environmentalists managed those challenges and even expanded their purview to international issues.

Amanda Tewes pick:

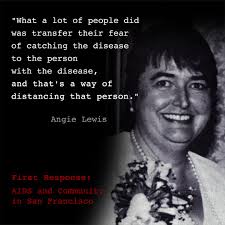

Paul Burnett’s pick:

I choose nurse educator and clinical nurse Angie Lewis, who worked at UC San Francisco during the early years of the AIDS crisis. In Lewis’ interview, we really hear what it was like to first learn of this then-unknown disease that was killing gay people in San Francisco in the early 1980s. But we also hear touching stories of the mobilization of community and medical support for those who were suffering from AIDS.

David Dunham’s pick:

David Blackwell: African American Faculty and Senior Staff Oral History Project. Named after an esteemed mathematician and the first African-American tenured professor at Cal, David Blackwell Hall opened this fall to honor Professor Blackwell. Read more about his pioneering life in his oral history, part of our African American and Senior Faculty Oral History Project.

Todd Holmes’ pick:

I’d recommend Francis Mary Albrier: Determined Advocate for Racial Equality. This oral history captures the extraordinary life of one of Berkeley’s most prominent citizens, from her leading role in fighting discriminatory hiring in the City’s schools and businesses to desegregating the famed Richmond Shipyards. Moreover, through her oral history, you get a clear view of the many unsung citizens that organized communities of color to collectively push for change.

Shanna Farrell’s pick:

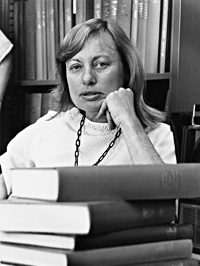

When I was first learning how to conduct longform interviews, I drew inspiration from Willa Baum, former director of the Oral History Center. She was an amazing interviewer, and her oral history interview provided insight into who she was, what drove her, and how she built the reputation of our office.

From the Director: October 2018

OHC Director Martin Meeker shares his work with the Oral History Association to update its core documents outlining best practices and ethical standards for the field. The committee, which Meeker is a part of, is seeking feedback through which is open for public comment through October 12, 2018.

![]()

Every decade or so, the Oral History Association (OHA) has convened a group of oral historians to examine, reconsider, and, often, redraft its core documents outlining best practices and ethical standards for the field. When Todd Moye assumed the presidency of OHA last fall, he announced that just such a project would be a key feature of his term. Soon a task force of fourteen members, including the excellent chairs Sarah Milligan and Troy Reeves, was established and a series of online meetings commenced. I was honored to be asked to serve on the task force and was very happy to work alongside so many accomplished scholars and dedicated oral historians.

Working fairly intensely for about nine months, the task force ultimately drafted six documents. Of those six, four are key. These include: Core Principles, Statement on Ethics, Best Practices, and what the committee is calling “For Participants in Oral History Interviews.” All of the documents are available for everyone to read online and the comment period remains open until October 12. Members of OHA will have the chance to give an up or down vote on the proposed new documents at the business meeting during upcoming OHA annual meeting on Saturday October 13.

As a member of the task force and as a deeply committed oral historian, I want to encourage everyone to engage with these documents both now and when, presumably, they are adopted. Unlike some previous iterations of these documents, the 2018 editions basically offer a full scale rethinking and rewrite of what came before. While there was much useful and insightful material in the previous versions and they served the organization well for years, many task force members thought that those documents both attempted to do “too much” and “too little.” I think that means that there were some pretty detailed prescriptions that were difficult to apply widely (“too much”) and yet much of what was written was a bit too vague and thus was difficult to implement in specific settings (“too little”). The current task force sought to remedy this, and we certainly hope that readers today agree.

The task force wrestled with a number of other questions that are either new or have become newly important over the past decade (the current version was adopted in October 2009). Not surprisingly, technology is at the top of the list. One way in which we attempted to deal with continuous technological innovation was to think about the universal questions and issues that the new innovations have summoned. In other words, we avoided getting into the weeds and writing specific instructions for the situation today because we know things will continue to evolve, and at a rapid rate. Although oral historians have long been aware of the potential challenges and needs that come with interviewing across lines of difference, there is certainly a greater sensitivity to “privilege” today, and the task force kept these concerns foremost when doing our work. But as with technology, we attempted to be open and not write the document so that it speaks only to one type of difference, privilege, or associated challenge, and instead provided guidelines and insight into the best way to handle sensitive relationships in a variety of situations.

When you read the documents, I encourage you to read first Sherna Berger Gluck’s “Introduction,” which provides a useful and tidy history of these documents over the decades, thus putting the newest versions in context. I think I can speak for my fellow task members in saying that we hope the work that we’ve done is received well and is seen as useful and valuable for, perhaps, the next 10 years.

Martin Meeker

Charles B. Faulhaber Director

Field Notes: More on Interviewing Around Trauma

by Shanna Farrell

@shanna_farrell

Trauma comes in many forms. So does the way we process this trauma, and the way we express it. For me, as an oral historian, this translates to how I conduct interviews and how I prepare for them. For the next couple of months, I’ll be reflecting on this for the OHC’s Field Notes section of our blog. I began this discussion in September, talking about a project that I’m working on with the Presidio Trust, a former U.S. Army base-turned National Park on the northern edge of San Francisco near the Golden Gate Bridge. We’re interviewing people who were involved in, or related to, the Presidio 27 mutiny that occured on October 14, 1968. Events in honor of the 50th anniversary will take place the weekend of October 13th and 14th at the Presidio.

Special care needs to be given to interviews that focus on trauma, as do the pre-interviews. The same rules do not apply for trauma-centric pre-interviews and the process must be flexible. Even just the idea of sitting down for an interview to recount these memories can be anxiety producing. It’s important for the interviewer to keep this in mind and be willing to adapt, or even abandon, their normal practices.

I was confronted with this recently for an upcoming interview. The narrator, who has been interviewed before for a book, agreed to participate in our project. During our first pre-interview, which I conducted with Presidio Historian, Barbara Berglund Sokolov, he expressed uncertainty about his memory and his ability to recall certain events. He was upfront about an illness that he lives with and the impact it has had on his life. He was specific about areas that he did not want discuss, which we noted and will respect.

He viewed this pre-interview, which lasted for about two hours, as the first of several. He requested that we put the interview outline together and mail it to him. Once he reviewed it, we would meet again to talk about the content. This is not normally how I operate. I usually have one meeting with a narrator wherein I schedule the interview. But, I needed to be flexible here, especially if I wanted to build rapport, create trust, and help cultivate a setting where he feels comfortable sharing his story. So we agreed to his request for multiple meetings before the actual interview.

Barbara and I put together interview outlines shortly after the first pre-interview meeting and mailed it off to the narrator. A couple of months passed until we met again. This time around, he seemed much more relaxed and comfortable. Though it was clear he hadn’t read the outline, we took no offense. We understood that he needed to read it in the company of others to discuss these memories and become more comfortable with doing the interview. This meeting lasted for another couple of hours, at the end of which he expressed his desire for more time. We agreed, because we wanted to ensure that he felt agency in the process.

Before the oral history interview, the three of us will have met at least three times. There will be more time spent doing pre-interviews than the actual interview. And this is okay. It may not be what I’m used to, but it feels right to allow the narrator his space to share his story on his terms. This is another form of shared authority, one of the many reasons that I feel so compelled by oral history. Our flexibility in the process will not only strengthen the interview, but hopefully it will allow the narrator the most support.