Author: Timothy Vollmer

Supporting open access book publishing at UC Berkeley: Summer 2021 update

The University of California has taken a multi-faceted approach to supporting open access (OA). For instance, UC’s open access policies ensure that university-affiliated authors can deposit their final, peer-reviewed research articles into eScholarship, our institutional repository, where the articles may be read by anyone for free. The UC has entered into several transformative open access agreements, with the dual goal of enabling universal open access to all UC research and containing the excessively high costs associated with licensing journals. UC also has been supporting new publishing models, such as Berghan Open Anthro’s Subscribe-to-Open.

At the local level, UC Berkeley Library continues to offer the Berkeley Research Impact Initiative (BRII). This program helps UC Berkeley authors defray article processing charges (APCs) that are sometimes required to publish in fully open access journals (note that BRII doesn’t reimburse authors for publishing in “hybrid” journals—that is, subscription journals that simply offer a separate option to pay to make an individual article open access). This past year BRII provided funding for the publication of 83 open access journal articles.

The Office of Scholarly Communication Services is involved in several efforts to help journals change from subscription access to open access, including through Transitioning Society Publication to Open Access (TSPOA), and the Open Access Community Investment Program (OACIP).

Ok, great. But what about books?

The number of open access books continues to grow. As of August 2021, the Directory of Open Access Books indexes 43,793 books. The Open Access Scholarly Publishing Association recently reported that over 1,600 open access books were published by its members in 2020, which represents a growth of over 16% over the previous year.

We know that not all University of California authors are publishing journal articles, and many disciplines—such as arts & humanities and social sciences—focus on the scholarly monograph (in other words, a book) as the preferred mode of publishing. And in contrast with journal articles, books typically cost significantly more to produce. At the systemwide level, the UC is supporting several open access book publishing ventures, including The Open Library of Humanities, which publishes open access scholarship with zero author facing charges, and Knowledge Unlatched, a collection of primarily open access book publishers seeking support from libraries.

So what is UC Berkeley doing to support OA book publishing? Let’s have a look.

Springer open access books partnership

In March 2021, UC Berkeley Library entered into the first-ever institutional open access book agreement with Springer Nature. The partnership provides open access funding to UC Berkeley affiliated authors who have books accepted for publication in Springer, Palgrave, and Apress imprints. This means that these authors can publish their books open access at no direct cost to them. The agreement covers all disciplines published by Springer. It will last for at least three years, and aims to support the publication of four open access books each year. All the books will be published under a Creative Commons Attribution license.

The first book published open access under the UC Berkeley-Springer agreement is Probability in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, written by Jean Walrand, Professor in the department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences at UC Berkeley. It is available as a CC-BY licensed PDF and EPUB.

Professor Walrand wrote in an email about open access and free digital downloads affect how students and other readers interact with the book.

“Digital resources are more convenient than printed material for searching, hyperlinking, frequent updates, and general access. They enable animations, videos, and interactions with the material, its users, and authors. Moreover, availability of code that complements publications is important in our field. Students are used to reading online. In STEM fields, printed materials are becoming obsolete. However, I believe that carefully edited material is valuable and that good publishers have a useful role to play as editors of digital resources. The open access model is a good step to evolve the role of publishers and libraries. This transition is happening quickly and is challenging.”

BRII support for open access books

We already mentioned how the Berkeley Research Impact Initiative helps UC Berkeley authors publish articles in fully open access journals. BRII funding can also be used to help authors pay book processing charges (up to $10,000/book) so that their monographs can be published open access.

BRII funding has helped several UC Berkeley authors make their books immediately available for free under Creative Commons licenses.

In May 2021 Integrative Biology Professor Brent Mishler published What, if anything, are species? The book is available for anyone to freely read and download under the CC-BY-NC license.

Last year, Jordan Gowanlock (UC Berkeley postdoc in the Department of Film and Media) completed Animating Unpredictable Effects: Nonlinearity in Hollywood’s R&D Complex. The open access book was published by Palgrave Macmillan under a CC-BY license.

Chris Hoofnagle, UC Berkeley Law Professor and Faculty Director of the Berkeley Center for Law & Technology, will publish Law and Policy for the Quantum Age in October 2021 through Cambridge University Press. The open access book was co-written with Simson Garfinkel and will be made available under a CC-BY-NC license. In an email, Professor Hoofnagle wrote about the importance of open access and the financial support he received from BRII:

“Publishing open access is critical to the academic success of this work. A book format was necessary to explain the history and nuances of quantum technologies. Open access gives the work the public availability of an article and the room needed to develop a story that can’t be told in an article-length exposition. We are thankful to BRII for this support.”

Open access at the University of California Press

UC Berkeley Library continues to support open access book publishing via Luminos, the OA arm of the University of California Press. The Library membership with Luminos means that UC Berkeley authors who have books accepted for publication through the UC Press can publish their book open access with a heavily discounted book processing charge. When combined with additional funding support through BRII, a UC Berkeley book author could potentially publish an OA book with the costs being covered fully by the Library. Luminos books are published under Creative Commons licenses with free downloads.

What Is a Family? Answers from Early Modern Japan was published by Luminos in 2019, with financial support from BRII. It was co-written by UC Berkeley Department of History Emerita Professor Mary Elizabeth Berry. What Is a Family? is available as an openly licensed ebook in EPUB, MOBI, and PDF formats.

Pressbooks open book platform

The UC Berkeley Library hosts a version of Pressbooks, an online platform through which the UC Berkeley community can create open access books, open educational resources (OER), and other types of digital scholarship. UC Berkeley authors have published several books via Pressbooks over the last year, including Euripides Scholia, The Discipline of Organizing, The Languages of Berkeley, and Building Legal Literacies for Text Data Mining.

Pressbooks provides for web viewing, as well as ebook downloads in a variety of formats, including PDF and EPUB. Anyone with an @berkeley.edu email can create and publish ebooks on Pressbooks. And, the Office of Scholarly Communication Services continues to offer small grants of up to $5,000 to Berkeley faculty or instructors who wish to create open educational resources or open textbooks that are aimed to be used in instruction.

Investing in the broader OA book publishing community

Back in April we wrote about how the UC Berkeley Library’s Collection Services Council was working to develop local best practices to guide investment in open access products and services. The Library is now working on an implementation plan that embeds the criteria into decision making about whether (and how) to invest in OA resources, memberships, and projects, including OA book publishing initiatives.

We’re starting to kick the tires of the review criteria and process based on requests we’ve already received to invest in new types of open access book support models. For example, the University of Michigan Press is testing a publishing model that asks for upfront investment from the library community in order to support new open access book publishing. Under their Fund to Mission Open Access Monograph Model, if the press meets a specific financial investment goal, they’ll make 50% of their 2022 titles open access. The more investment they receive from the library community, the greater percentage they publish open access from the get go. Libraries are granted term access to their backlist for the duration they are offering support. UC Berkeley Library has evaluated the proposal of the University of Michigan Press Ebook Collection and decided to financially support the initiative for the next three years.

Wrapping up

In this post, we discussed the many ways that the University of California—and specifically UC Berkeley—is supporting scholarly authors to create and share open access books. In addition to providing financial assistance, platforms, and publishing guidance, the Library is committed to promoting the broader OA book publishing ecosystem through strategic investment of our collections budget. We’ll continue to explore a variety of approaches to support the UC Berkeley community (and beyond) who wish to publish books on open access terms.

If you’re interested to learn more about how you can create and publish and open access book, visit our website or send an email to schol-comm@berkeley.edu.

Now available: Open educational resource of Building Legal Literacies for Text Data Mining

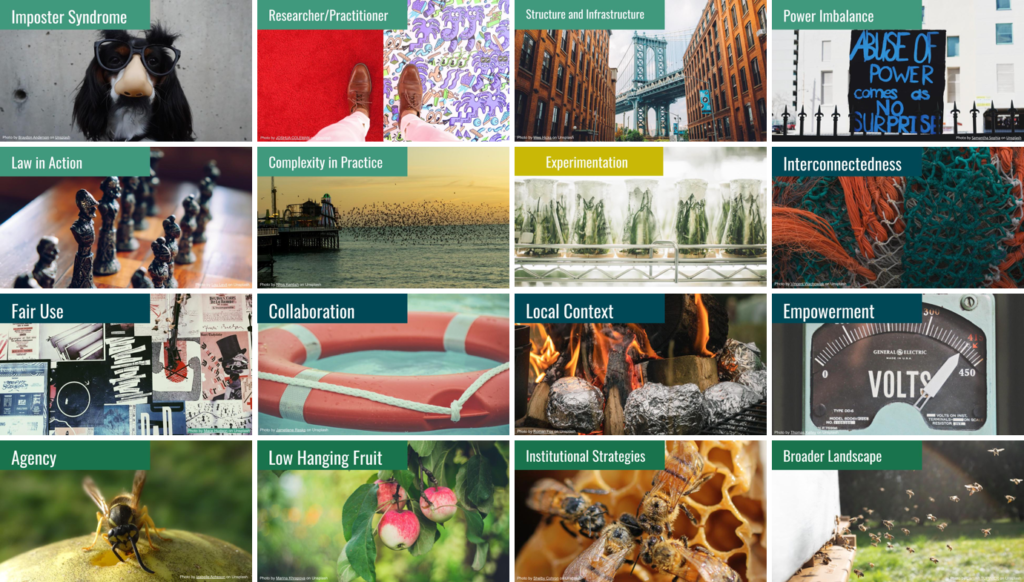

Last summer we hosted the Building Legal Literacies for Text Data Mining institute. We welcomed 32 digital humanities researchers and professionals to the weeklong virtual training, with the goal to empower them to confidently navigate law, policy, ethics, and risk within digital humanities text data mining (TDM) projects. Building Legal Literacies for Text Data Mining (Building LLTDM) was made possible through a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Since the remote institute in June 2020, the participants and project team reconvened in February 2021 to discuss how participants had been thinking about, performing, or supporting TDM in their home institutions and projects with the law and policy literacies in mind.

To maximize the reach and impact of Building LLTDM, we have now published a comprehensive open educational resource (OER) of the contents of the institute. The OER covers copyright (both U.S. and international law), technological protection measures, privacy, and ethical considerations. It also helps other digital humanities professionals and researchers run their own similar institutes by describing in detail how we developed and delivered programming (including our pedagogical reflections and take-aways), and includes ideas for hosting shorter literacy teaching sessions. The resource (available as a web-book or in downloadable formats including PDF and EPUB) is in the public domain under the CC0 Public Domain Dedication, meaning it can be accessed, reused, and repurposed without restriction.

In addition to the OER, we’ve also published a white paper that describes the institute’s origins and goals, project overview and activities, and reflections and possible follow-on actions.

Thank you to the National Endowment for the Humanities, the project team, institute participants, and staff at the UC Berkeley Library for making Building LLTDM a success.

[Note: this content is cross-posted on the LLTDM blog.]

Reporting back on our ACRL 2021 conference panel: Open access investment at the local level

Last year the UC Berkeley Library’s Collection Services Council charged a working group to develop local best practices to guide investment in open access (OA) products and services. Advancing open access to scholarship is one of the Library’s key goals, and addressing how and when UCB invests in OA resources and materials is one path to supporting this priority. In May 2020 the working group completed its report, recommending key criteria and a workflow for evaluating open access investment opportunities.

Even though the Library is in the early stages of implementing the proposed criteria and review process, we submitted a proposal for the 2021 ACRL Conference to share our work with the broader academic library community and to receive feedback as we develop the process. We also wanted to hear how related projects address open access investments, and understand the challenges (and hopefully, solutions) others have encountered along the way.

Our panel was titled Open access investment at the local level: Sharing diverse tactics to improve access & affordability. We know that many decisions about open access investments take place at administrative or consortial levels, but librarians frequently field requests for access, resources, or partnerships at the local level through their relationships with students, researchers, and faculty. The panel aimed to share real-world examples of where and how academic libraries decide to invest in open access resources, and discuss commonalities and differences in strategies and give attendees examples they can apply in their own roles.

Panelists included:

- Sam Teplitzky, Open Science Librarian, UC Berkeley

- Timothy Vollmer, Scholarly Communication & Copyright Librarian, UC Berkeley

- Sharla Lair, Senior Strategist, Open Access & Scholarly Communication Initiatives at LYRASIS

- Tom Narock, Assistant Professor of Data Science at Goucher College

- Justin Gonder, Senior Product Manager, Publishing, California Digital Library

Tim discussed the findings and recommendations of the UC Berkeley Library Open Access Investment Working Group, including the main criteria and processes by which the Library could evaluate open access investment opportunities. Sharla outlined the Open Access Community Investment Program, a new community-funded OA publishing program launched by LYRASIS and Transitioning Society Publications to Open Access (TSPOA). It aims to match nonprofit publishers who are seeking financial investments with funders looking to support OA publishing projects. Tom and Justin talked about the goals and infrastructure required to support preprint servers such as EarthArXiv, and explained the partnership that EarthArXiv entered into with the California Digital Library. Sam led the group discussion at the end of the panel.

We thank the panelists for their time and engaging conversation, and hope the discussion sparks ideas for open investments beyond Berkeley. You can view the panel presentations and discussion below. If you have questions or comments, please send them to schol-comm@berkeley.edu.

Law & ethics in research and archiving social media of Myanmar resistance

On March 9, 2021, the Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Institute of East Asian Studies, the Institute of South Asia Studies, and the Human Rights Center at UC Berkeley hosted the online symposium Scholar-Activism and the Myanmar Resistance. The event invited scholar-activists to analyze and strategize for resistance to Myanmar’s military coup. The Office of Scholarly Communication Services collaborated with Dr. Hilary Faxon, Ciriacy-Wantrup Postdoctoral Fellow at UC Berkeley, to organize an afternoon workshop to explore the law, ethics, methods, and goals of archiving social media coverage of the coup.

Faxon highlighted that in the months since the military seized power on February 1, the internet has become a key domain of struggle in Myanmar. The military has cut off internet access and (before being banned) used Facebook to disseminate misinformation. Meanwhile, democracy activists have used social media alongside traditional tactics of street protests and general strikes to resist the regime.

The workshop brought together a diverse group of participants from across and beyond campus with perspectives from human rights, research and journalism, including WITNESS and Berkeley’s Human Rights Investigation Lab. Stacy Reardon, Literatures and Digital Humanities Librarian, discussed services and workshops offered by Digital Humanities at Berkeley, as well as tools used to conduct DH research, such as the Wayback Machine, Conifer, 4k download, Adobe Bridge, and others.

The Office of Scholarly Communication Services provided an overview for how to navigate law and policy issues when researchers are scraping, archiving, or text mining third party content, like social media posts, website text or images, or articles from databases. We addressed common issues that arise in research and archiving, including copyright, license agreements and website terms of use, privacy questions, and ethical considerations.

Workshop discussions were centered around a commitment to a shared ethics of care approach to using, sharing, and archiving information social media content related to the coup. The ethics of care framework suggests that what we do as information collectors or analyzers will affect other people, particularly when people have less structural power, and according to the ethics of care, we should care about that. This becomes immediately apparent when deciding whether or how to collect, process, and share potentially sensitive social media posts, images, and videos from the Myanmar coup, especially when doing so could have dire consequences for activists who are the subjects of those posts.

During the workshop, we talked about how the Library has adopted a form of ethics of care in our approach to making decisions about what collection materials we’ll digitize and put online. Our version of ethics of care is framed as a balancing principle: that is, we look to whether the value to researchers, the public, or cultural communities in digitizing and sharing the content outweighs the potential for harm or exploitation of people, resources, or knowledge.

Several takeaways emerged by the end of the workshop discussion:

- Protecting and defending human rights: Archiving material from social media—including videos, photos, and live streams—might help ensure perpetrators of violence are held accountable, but the production and circulation of such materials can also be highly-incriminating for media creators and platform users.

- Collecting is collaborative: Usage of archives is bound up with the intentions of those creating material, and so archiving requires an ongoing, bi-directional conversation between those creating content and those doing the archiving.

- Circumstances change: Both ethical and organizational approaches should be discussed and decided in advance of archiving. But expect situations to change – what is safe and straightforward to keep today may be more risky tomorrow.

- Capturing versus sharing: These are different processes, and “archiving” does not necessarily have to entail both. The benefits and risks associated with collecting data are distinct from those associated with sharing data or making it publicly available, so these processes should be considered separately.

- Law and ethics: Regardless of what is allowed under U.S. copyright law, there may be other contracts and terms of service that restrict what you can do with materials. Moreover, collecting voluntarily-released data may not violate legal privacy rights, but may present ethical questions.

- Data security: Develop a Data Management Plan that addresses organization and protection both during archiving, and after the project is completed. Consider a special purpose account for collaborations and data sharing.

- Data hygiene: Don’t collect more than you need.

- Practical strategies: Tools may depend on the specific goals of a researcher and the scale of the project. It is important to ask what, precisely, you mean when you say “archiving,” and what the purpose of creating your archive might be.

- Seek out a community of practice to support and situate your efforts.

We hope the workshop helped researchers to better understand the legal and ethical considerations in collecting, processing, and sharing potentially sensitive social media content of events like the Myanmar resistance. The Library and a broad community of supporters are here to help scholars address these challenges and equip them to proceed with confidence, care, and sound practices.

Springer Nature and UC Berkeley Library sign new open access book partnership

Cross-posted at Springer Nature.

Agreement to publish open access books across all subject areas will increase the reach and impact of future publications.

Berkeley | Heidelberg | London, 23 March 2021

Springer Nature has signed its first ever institutional open access (OA) book agreement with the University of California, Berkeley Library. The agreement will cover a broad range of book titles across all disciplines — from humanities and social sciences to sciences, technology, medicine and mathematics and, starting in 2021 and running for at least three years, will provide open access funding to UC Berkeley affiliated authors. The open access book titles will publish under the Springer, Palgrave, and Apress imprints, with initial titles set to publish later this year.

This agreement with UC Berkeley Library follows the UC systemwide landmark transformative agreement with Springer Nature announced last year to enable UC authors to publish research articles open access in over 2700 Springer Nature journals. While the transformative deal covers the publication of journal articles, books are the common or expected publishing format in some disciplines. The need to account for a variety of scholarly outputs prompted UC Berkeley Library to sign a new agreement providing direct assistance to book-publishing authors.

The books will be published under a CC BY licence and readers around the world will have free access to the books via Springer Nature’s content platform SpringerLink. With research showing that open access books are downloaded ten times more often and cited 2.4 times more, this important agreement will significantly enhance the visibility, dissemination and impact of important academic research.

Niels Peter Thomas, Managing Director Books, Springer Nature, said:

“We are delighted to be partnering with UC Berkeley Library in what is our first ever institutional partnership for open access books and our first US agreement for open access books. This represents a big step towards ensuring access to funding for book authors. By utilising our experience as the largest academic book publisher and expertise in enabling the transition to open access, we look forward to increasing the impact and reach of book authors at UC Berkeley and their research.”

Jo Anne Newyear-Ramirez, UC Berkeley Library’s Associate University Librarian for Scholarly Resources, said:

“UC Berkeley Library has been working with publishers to create sustainable and inclusive paths to open access, for both scholarly articles and books. For the past several years, through our Berkeley Research Impact Initiative, we have covered a significant portion of book processing charges for any open access book our authors publish, but this agreement with Springer Nature takes an even bigger leap forward. Under this agreement, we will cover 100% of standard publishing costs for open access books that UC Berkeley authors publish with Springer Nature for at least the next three years. This will help yield important progress on our journey to advance knowledge by making more UC Berkeley-authored books open to the world. We’re equally thrilled to be pioneers among U.S. academic institutions in entering into this type of agreement with Springer Nature.”

END

About UC Berkeley Library

The UC Berkeley Library is an internationally renowned research and teaching facility at one of the nation’s premier public universities. With 24 distinct destinations, including Doe and Moffitt libraries, The Bancroft Library, the C. V. Starr East Asian Library, and an array of subject specialty libraries, the UC Berkeley Library offers services and materials that span the disciplines. The Library holds paintings, lithographs, papyri, audio and video recordings, and books, and offers robust services that connect users with these remarkable resources — and more — to inform their research and advance their understanding of the world.

About Springer Nature

For over 175 years Springer Nature has been advancing discovery by providing the best possible service to the whole research community. We help researchers uncover new ideas, make sure all the research we publish is significant, robust and stands up to objective scrutiny, that it reaches all relevant audiences in the best possible format, and can be discovered, accessed, used, re-used and shared. We support librarians and institutions with innovations in technology and data; and provide quality publishing support to societies.

As a research publisher, Springer Nature is home to trusted brands including Springer, Nature Research, BMC, Palgrave Macmillan and Scientific American. For more information, please visit springernature.com and @SpringerNature

Contact

UC Berkeley Library: With questions about this agreement, please contact UC Berkeley Library’s Office of Scholarly Communication Services: schol-comm@berkeley.edu.

Springer Nature: Felicitas Behrendt | Communications Manager | Felicitas.behrendt@springernature.com | T +49 (0) 6221 487 9901

UC’s new copyright ownership policy: What does it mean for campus?

The University of California has released an updated copyright ownership policy (and accompanying FAQ). This is the policy across all of the UC campuses that governs who (as between the University or the author) owns copyright in scholarly and aesthetic works created by faculty, staff, and students. The copyright ownership policy was last revised in 1992. The Library submitted comments on the draft policy in December 2019, and many of our proposed suggestions and clarifications have been included.

But what does the updated copyright policy mean for different groups and individuals around campus? This post will break down some of the changes in the new policy.

What types of works are eligible for copyright ownership?

Quick Answer: Any copyrightable works created by Academic Authors within the scope of their employment as part of their teaching, research, or scholarship are eligible for copyright ownership. This includes (but is not limited to) journal articles, textbooks, course materials, and more. And now, Academic Authors are eligible to own copyright in software they create.

Read More: The revised copyright ownership policy includes a new definition: Scholarly & Aesthetic Works. These are “copyrightable works authored by Academic Authors within the scope of their employment as part of or in connection with their teaching, research, or scholarship.” Academic Authors hold copyright in these works when they are created without direct assignment or supervision by the University. The policy provides a non-exhaustive list of works that will be considered Scholarly & Aesthetic Works, such as journal articles, books, case examples, course materials, and visual works of art. Importantly, the updated policy includes software as a category in which Academic Authors may hold copyright (although the UC continues to own the patent rights created in software).

When do authors own their copyrights?

Quick Answer: Now, any employee who has a “general obligation to create copyrightable scholarly or aesthetic works” gets to keep their copyright in those works. Note that students always hold copyright in anything they create while at the UC, unless certain conditions apply (e.g. the student created a copyrightable work in the scope of their employment, it was part of a sponsored grant project, etc.).

Read More: Under U.S. copyright law, the copyright in a work prepared by an employee in the course of their employment typically resides with the employer. The revised copyright ownership policy continues the practice whereby the University transfers any copyrights it may own in Scholarly & Aesthetic Works to the Academic Authors who prepared those works.

The updated copyright ownership policy expands the definition of “Academic Authors” eligible to own copyrights. Now, Academic Authors means “employees who have a general obligation to create copyrightable scholarly or aesthetic works.” Sometimes it’s relatively clear which employees have a general obligation to create copyrightable works, such as Senate faculty when they conduct and publish research. And represented librarians bear a “general obligation” to produce scholarly works because, under their labor contract and review criteria, creating scholarship is a factor affecting career advancement.

But what about other campus employees whose job descriptions are less clear and who have no clarifying labor contract? To help you figure out whether you have a “general obligation” to create scholarly works, you can consult copyright ownership policy FAQ #9, which basically says that there is likely some document in writing—whether a contract or written job description or documentation—that would suggest that creating scholarly works is part of your job. In instances where it’s not clear from that documentation, employees may want to consult with their supervisors to discuss the matter.

One other note on collective bargaining agreements. The revised copyright ownership policy contains a provision that if there’s a conflict between it and a union agreement governing copyright ownership by represented employees, then the union agreement prevails.

Note that students (as opposed to employees) always hold copyright in anything they create while studying at the UC, unless certain conditions apply (e.g. the student created a work in the scope of their employment, it was part of a sponsored grant project, etc.) The new copyright ownership policy also clarifies that works created by graduate students (such as theses, dissertations, etc.) are considered “Student Works,” thus under most circumstances the copyright resides with the graduate student.

When does the University (rather than the author) own copyrights?

Quick Answer: The University holds the copyright for works created by employees who do not have a “general obligation” to create scholarly works, for most grant-sponsored or commissioned works, and for works that require “Significant University Resources” in the creation of the work.

Read More: There are several common situations in which the University owns the copyright in works created by employees:

- When the work is created by an employee who does not have a “general obligation to create scholarly and aesthetic works”: This remains largely unchanged from the previous policy.

- When the work is a sponsored or commissioned work: Sponsored or commissioned works are typically situations in which the University has entered into a separate written agreement with the employee, such as for certain grants or special projects. But the definition of “sponsored works” has been clarified in the new policy so that it’s clear that Academic Authors retain copyright in scholarly articles or other works created based on the underlying findings or deliverables of the sponsored project.

- When the work was created with significant university resources: Under the old policy, the University could claim copyright ownership to the works produced by Academic Authors if the author leveraged any “University Resources” while creating the material. The revised copyright ownership policy further limits the cases where this would apply. Now, the University may not claim copyright ownership unless “Significant University Resources” were used to facilitate creation of the work. For something to be considered significant, it must be “beyond the usual support provided by the University and generally available to similarly situated Academic Authors.” And the policy clarifies that support such as customary administrative assistance, library facilities, office space, personal computers, network access, and salary are considered usual support and will not be deemed “significant.” FAQs #14-17 provide more information on “Significant University Resources.”

In sum, the new copyright ownership policy provides some useful clarity for authors to understand when they hold the copyright. And in a few important ways, it expands and strengthens the ability for these authors to hold copyright in works they produce at the UC.

If you have any questions, please contact schol-comm@berkeley.edu.

Spring 2021 workshops from the Office of Scholarly Communication Services

Once again this semester the Office of Scholarly Communication Services will offer workshops as part of the Library’s Digital Publishing Series. Here’s what’s coming up over the next few months.

Upcoming Workshops

Publish Digital Books and Open Educational Resources with Pressbooks

Tuesday, February 9, 2021

2:00–3:30pm

Online: Register to receive the Zoom link

If you’re looking to self-publish work of any length and want an easy-to-use tool that offers a high degree of customization, allows flexibility with publishing formats (EPUB, MOBI, PDF), and provides web-hosting options, Pressbooks may be great for you. Pressbooks is often the tool of choice for academics creating digital books, open textbooks, and open educational resources, since you can license your materials for reuse however you desire. Learn why and how to use Pressbooks for publishing your original books or course materials. You’ll leave the workshop with a project already under way.

Text Data Mining and Publishing

Tuesday, March 16th, 2021

11:00am–12:30pm

Online: Register to receive the Zoom link

If you are working on a computational text analysis project and have wondered how to legally acquire, use, and publish text and data, this workshop is for you! We will teach you 5 legal literacies (copyright, contracts, privacy, ethics, and special use cases) that will empower you to make well-informed decisions about compiling, using, and sharing your corpus. By the end of this workshop, and with a useful checklist in hand, you will be able to confidently design lawful text analysis projects or be well positioned to help others design such projects.

Other ways we can help

In addition to the workshops, we’re here to help answer a variety of questions you might have on intellectual property, digital publishing, and information policy.

- Check out our website for information on issues such as copyright and fair use, the scholarly publishing lifecycle and sharing research data, UC’s Open Access Policy.

- Interested in publishing your research Open Access? UCB Library can help defray the costs of an article processing charge (up to $2,500) or book processing charge (up to $10,000). See the Berkeley Research Impact Initiative (BRII) for more information.

- Do you want to create an open digital textbook? Take a look at UC Berkeley’s Open Book Publishing platform (anyone with a @berkeley.edu email can signup for a free account), and get in touch with us about our Open Educational Resources (OER) grant program.

- Keep an eye on our events calendar for more workshops and trainings.

- Follow our blog and social media.

Want help or more information? Send us an email. We can provide individualized support and personal consultations, online class instruction, presentations and workshops for small or large groups & classes, and customized support and training for departments and disciplines.

Upcoming workshop on how to share and publish data

Are you unsure about how you can use or reuse other people’s data in your teaching or research, and what the terms and conditions are? Do you want to share your data with other researchers or license it for reuse but are wondering how and if that’s allowed? Do you have questions about university or granting agency data ownership and sharing policies, rights, and obligations? We will provide clear guidance on all of these questions and more in this interactive webinar on the ins-and-outs of data sharing and publishing.

Join the Library’s Office of Scholarly Communication Services and the Research Data Management Program as we:

- Explore venues and platforms for sharing and publishing data

- Unpack the terms of contracts and licenses affecting data reuse, sharing, and publishing

- Help you understand how copyright does (and does not) affect what you can do with the data you create or wish to use from other people

- Consider how to license your data for maximum downstream impact and reuse

- Demystify data ownership and publishing rights and obligations under university and grant policies

Intended audiences include faculty, grad students, post-docs, instructors, and academic support staff, but anyone interested is welcome to attend.

Fall workshops on copyright and publishing

Welcome back to a strange semester. While we can’t meet up together on campus, the Office of Scholarly Communication Services will continue to offer a full slate of online workshops to help students and early career researchers confidently steer their way through the waters of copyright and publishing. Here is what’s in store for the coming few months.

Upcoming Workshops

Publish Digital Books and Open Educational Resources with Pressbooks

September 15, 2020

10:00–11:30am

If you’re looking to self-publish work of any length and want an easy-to-use tool that offers a high degree of customization, allows flexibility with publishing formats (EPUB, MOBI, PDF), and provides web-hosting options, Pressbooks may be great for you. Pressbooks is often the tool of choice for academics creating digital books, open textbooks, and open educational resources, since you can license your materials for reuse however you desire. Learn why and how to use Pressbooks for publishing your original books or course materials. You’ll leave the workshop with a project already under way! Signup at the link below and the Zoom login details will be emailed to you.

Copyright and Your Dissertation

October 19, 2020

1:00–2:30pm

This workshop will provide you with a practical guidance for navigating copyright questions and other legal considerations for your dissertation or thesis. Whether you’re just starting to write or you’re getting ready to file, you can use our tips and workflow to figure out what you can use, what rights you have as an author, and what it means to share your dissertation online.

Managing and Maximizing Your Scholarly Impact

October 20, 2020

1:00–2:30pm

This workshop will provide you with practical strategies and tips for promoting your scholarship, increasing your citations, and monitoring your success. You’ll also learn how to understand metrics, use scholarly networking tools, evaluate journals and publishing options, and take advantage of funding opportunities for Open Access scholarship.

From Dissertation to Book: Navigating the Publication Process

October 22, 2020

1:00–2:30pm

Hear from a panel of experts—an acquisitions editor, a first-time book author, and an author rights expert—about the process of turning your dissertation into a book. You’ll come away from this panel discussion with practical advice about revising your dissertation, writing a book proposal, approaching editors, signing your first contract, and navigating the peer review and publication process.

Copyright and Fair Use for Digital Projects

November 10, 2020

11:00am–12:30pm

This training will help you navigate the copyright, fair use, and usage rights of including third-party content in your digital project. Whether you seek to embed video from other sources for analysis, post material you scanned from a visit to the archives, add images, upload documents, or more, understanding the basics of copyright and discovering a workflow for answering copyright-related digital scholarship questions will make you more confident in your publication. We will also provide an overview of your intellectual property rights as a creator and ways to license your own work.

Archived Recordings

We hosted a few workshops over the summer that might be of interest to you.

Copyright in Course Design & Digital Learning Environments

Video Recording

Slides

If you’re wondering what you can or can’t upload and distribute in your online courses, we’re here to help with answers and best practices. We will cover copyright, fair use, and contractual issues that emerge in online course design. The goal of the webinar is for attendees to gain a deeper understanding of the legal considerations in creating digital courses, and to feel more confident in their content design decisions to support student learning. This webinar is appropriate both for instructors and staff supporting online courses.

Can We Digitize This? Understanding Law, Policy, & Ethics in Bringing our Collections to Digital Life

Video Recording

Slides

As part of the Digital Lifecycle Program, the UC Berkeley Library aims to digitize 200 million items from its special collections (rare books, manuscripts, photographs, archives, and ephemera) for the world to discover and use. But before we can digitize and publish them online for worldwide access, we have to sort out legal and ethical questions. We’ve created and released “responsible access workflows” that will benefit not only our Library’s digitization efforts, but also those of cultural heritage institutions such as museums, archives, and libraries throughout the nation.

Building Legal Literacies for Text Data Mining Institute

Video Recordings

Transcripts + Slides

In June, we welcomed 32 digital humanities (DH) researchers and professionals to the Building Legal Literacies for Text Data Mining (Building LLTDM) Institute. Our goal was to empower DH researchers, librarians, and professional staff to confidently navigate law, policy, ethics, and risk within digital humanities text data mining (TDM) projects—so they can more easily engage in this type of research and contribute to the further advancement of knowledge.

Other ways we can help

In addition to the workshops, we’re here to help answer a variety of questions you might have on intellectual property, digital publishing, and information policy.

- Check out our website for information on issues such as copyright and fair use, the scholarly publishing lifecycle and sharing research data, UC’s Open Access Policy.

- Interested in publishing your research Open Access? UCB Library can help defray the costs of an article processing charge (up to $2,500) or book processing charge (up to $10,000). See the Berkeley Research Impact Initiative (BRII) for more information.

- Do you want to create an open digital textbook? Take a look at UC Berkeley’s Open Book Publishing platform (anyone with a @berkeley.edu email can signup for a free account), and get in touch with us about our Open Educational Resources (OER) grant program.

- Keep an eye on our events calendar for more workshops and trainings.

- Follow our blog and social media.

Want help or more information? Send us an email. We can provide individualized support and personal consultations, online class instruction, presentations and workshops for small or large groups & classes, and customized support and training for departments and disciplines.

What happened at the Building LLTDM Institute

This update is cross-posted from the Building LLTDM blog.

On June 23-26, we welcomed 32 digital humanities (DH) researchers and professionals to the Building Legal Literacies for Text Data Mining (Building LLTDM) Institute. Our goal was to empower DH researchers, librarians, and professional staff to confidently navigate law, policy, ethics, and risk within digital humanities text data mining (TDM) projects—so they can more easily engage in this type of research and contribute to the further advancement of knowledge. We were joined by a stellar group of faculty to teach and mentor participants. Building LLTDM is supported by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Why was the Institute needed?

Until now, humanities researchers conducting text data mining in the U.S. have had to maneuver through a thicket of legal issues without much guidance or assistance. As an example, take a researcher scraping content about Egyptian artifacts from online sites or databases, or downloading videos about Egyptian tomb excavations, in order to conduct automated analysis about religion or philosophy. The researcher then shares these content-rich data sets with others to encourage research reproducibility or enable other researchers to query the data sets with new questions. This kind of work can raise issues of copyright, contract, and privacy law. It can also raise concerns around ethics, for example, if there are plausible risks of exploitation of people, natural or cultural resources, or indigenous knowledge.

Potential law and policy hurdles do not just deter text data mining research: They also bias it toward particular topics and sources of data. In response to confusion over copyright, website terms of use, and other perceived legal roadblocks, some digital humanities researchers have gravitated to low-friction research questions and texts to avoid making decisions about rights-protected data. When researchers limit their research to such sources, it is inevitably skewed, leaving important questions unanswered, and rendering resulting findings less broadly applicable.

Moving an interactive, design-thinking Institute online

After months of preparation, we had been looking forward to working and learning together at UC Berkeley, but the world had other plans for our Institute. Due to the global health crisis, we had to transform our planned in-person, intensive workshop into an interactive and relevant remote experience.

How did we do this? The pandemic meant we had to transition everything online, which of course presents challenges for a design-thinking framework. We are thrilled that our approach to interactive remote pedagogy was successful! (You can check out the schedule and framework in our Participant Packet.) The substantive content was pre-recorded and delivered in a flipped classroom model. Faculty created a series of short videos, and shared readings relevant to the legal literacies. We also provided the video transcripts and slides to participants to promote accessibility and accommodate multiple learning styles.

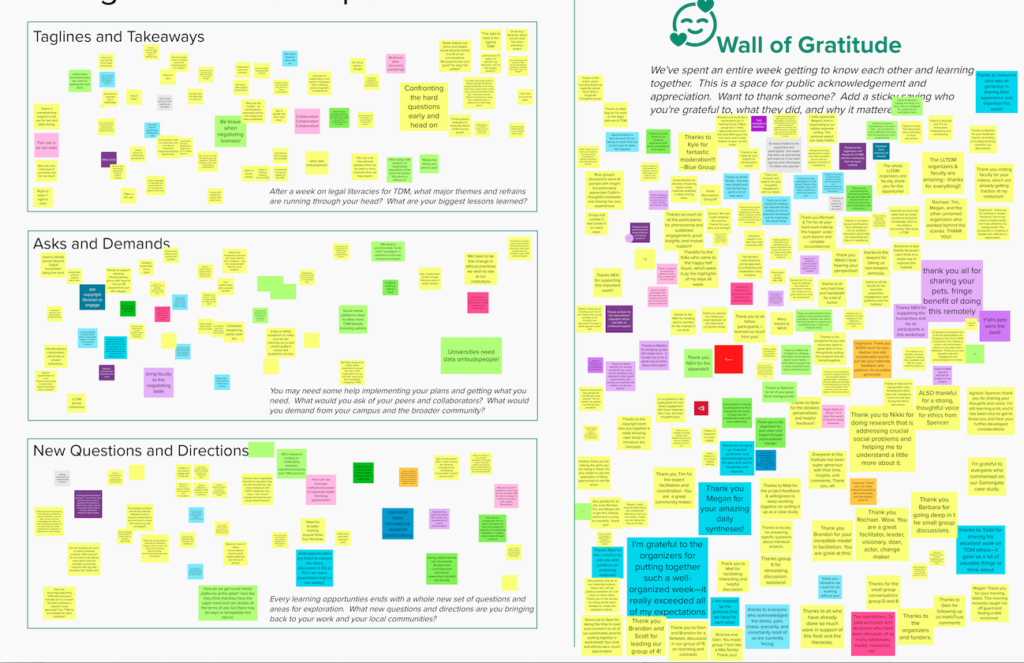

We used Zoom to meet synchronously for discussion in groups of various sizes. We used Slack for asynchronous communication, and interactive tools such as Mural for design thinking exercises like journey mapping so that everyone could live edit and collaborate. We capped each day with a “happy half hour” on Zoom as an informal way to get to know each other a little better, even from afar.

We also relied on an institute moderator and daily writing exercises to reinforce the design-thinking stages and learning outcomes. Each night, we reviewed the participants’ free-writes and began the next morning by reflecting back to the participants the themes from what they had shared.

Reflections on goals: social justice & effective empowerment

One of our priorities for the Institute was to invite a diverse pool of participants, including those involved in social justice research, in order to maximize the public value impact of Building LLTDM. We looked for demonstrated commitments to diversity and equity but could hardly have imagined the breadth and depth of experiences that applicants were willing to share. The selected participants research everything from understanding “place” data from community histories of historic African American settlements to the development of AIDS activist networks in communities of color; to portrayals of autism in literature; and more. Others demonstrated a commitment to bringing back the skills they learn to expand TDM opportunities for students and communities who have traditionally been marginalized or under-resourced. They also came from a variety of institution types, from research advising and support experience, professional roles, levels of experience with TDM, career stages, and disciplinary perspectives.

We are also moved by the participants’ own reflections on the experience. One of the last interactive exercises we hosted during the online Institute was a collective week-in-review discussion, and gratitude wall. We asked the participants to share what they were thankful for, highlighting other participants where possible. So many of the participants wrote about how valuable the learning experience was and how thoughtfully it was put together and delivered.

We can’t express the transformational impact of the week better than the participants, themselves. In Institute evaluation forms, they shared feelings like:

- “This is by far the best organized event that I have ever attended. The content was by far the most substantive. The faculty were by far the most engaged. A+ across the board.”

- “I am so grateful to have had the opportunity to engage with a diverse group of scholars (researchers and professionals)… The deliberately thought through breakdown and mix fostered incredibly valuable discussions and I would hope this kind of framework is used as a best practice for future DH institutes of all kinds going forward. Also, thank you for such an amazing virtual experience which I can only imagine took a tremendous amount of work to coordinate and plan with limited time to shift to an entirely different format–I was overjoyed to critically engage with complex subjects…”

- “This has been phenomenal. I don’t want to qualify it (by adding something like “…for having to be moved online”), because it’s been so, so good: well organized, thoughtful, and human throughout.”

- “There was clearly so much thought, care, and planning that went into the preparation of this institute, and it was an amazing opportunity to learn from a group of people — organizers, faculty, and participants — who all have such deep expertise. The video and readings lists alone are a huge resource, but to be able to process and reflect on that material together with a diverse group of people was really wonderful.”

Next steps, and our own gratitude

What’s next for Building LLTDM? The “Institute” is not over yet; only the 1-week training is complete. The cohort will be meeting again virtually in February 2021 to discuss how implementation of the literacies into our local communities and practices has gone. In the meantime, as the participants bring back the law and policy literacies they’ve learned to their home institutions, we are excited to see several cohort members already organizing their own post-Institute research subgroups, such as those whose TDM work relies heavily on social media content, and others who are exploring how to disseminate the Building LLTDM literacies within other instructional formats and frameworks.

As part of the grant, the project team will also be aggregating the resources from the Institute and developing supplementary material for an Open Educational Resource (OER). We know there is a large community of TDM researchers and professionals who may be interested in or who can benefit from these materials, and the OER will be made available for broad reuse in the public domain.

Thank you to all the participants for their insights and contributions, willingness to share, and flexibility in transitioning to a fully-remote Institute. Thank you to all the faculty for their unmatched legal and policy expertise, ongoing commitment to mentorship, and adaptability in content creation and delivery. And thank you again to the NEH for making such a meaningful experience possible.