Author: sfarrell

OHC Director’s Column for March 2021 features Guest Contributor Shanna Farrell

The Importance of Rapport

by Shanna Farrell, March 2021 Guest Contributor

A smile. A nod. A set of shoulders relaxing. A story seldom told. A handwritten note expressing gratitude. These are all examples of rapport, the genuine human connection forged between an interviewer and a narrator.

Sometimes, when you’re lucky, it happens naturally. There’s an ease between you and your narrator, a kind of simpatico that makes you feel like you’ve known each other for a long time. But in most cases, rapport needs to be earned, built slowly over time in a myriad of ways. Perhaps you have a shared experience, like growing up around horses. Perhaps you share interests, like a favorite author or movie or hike. Perhaps you went to the same college. Perhaps you have nothing in common, but you listen to each other talk without interrupting. Perhaps you look at each other in the eye, and are always on time, and after a while, you become sympathetic to one another, despite your differences.

Whenever we talk about oral history interviewing, we talk about rapport. It can come in many shapes and sizes. We discuss how to cultivate it during our Introductory Workshop and Advanced Summer Institute, trying to impress upon those who are there to learn from us how it can impact an oral history. Though there are no magic tricks for creating it with someone―aside from treating them as you’d like to be treated―it’s one of the most important elements of an interview. It affects so many things: the stories told; language used to describe something; the openness a narrator feels; how comfortable an interviewer is asking tough questions; the willingness to shed performative layers; the ability to bear witness to a person’s experiences.

I’ve been in situations where I have good rapport with a narrator. It’s something I’ve felt innately, through all of those nonverbal cues. It showed up in the interview, too, evident in the honesty of an answer and inclination to dig a little deeper, reflect a bit further. You can hear it in the recording, read it in the transcript, see in the tears that are shed on camera. These are the moments that I love―the ones filled with a common humanity―and keep me engaged in the oral history process.

And then there are times that I don’t have rapport with a narrator. The times I’ve used a word―like “strategy”―that I think is innocuous, but is loaded for them. Times that I’ve expressed that I, too, lived in Brooklyn, but it’s not enough to bridge our gap. The times that no matter how much I smile or make eye contact or nod that I can’t get them to open up, to lower the walls they’ve built to protect themselves. But I never stop trying. These are the moments that make me want to keep going, keep working.

In the time before COVID-19, it was much easier to read these situations. When I was in the same room as the person whom I was interviewing, I could usually tell if something was or wasn’t working, our interactions not flattened by a screen. But now that we’re a year into the pandemic, cultivating rapport is more difficult. When we’re so physically distant from our narrators. We might meet them first over email or the phone, maybe even through a letter. Our first opportunity to smile at them may come right before the interview begins as we’re double checking the settings on our computers. Or we may never have that chance, particularly when the interview is done over the phone. Silences may be misinterpreted, nods go unnoticed, cues from our bodies unheeded.

To be clear, I think it’s important to keep interviewing during this time. We need to document our experiences and keep reflecting on our lives. It’s also necessary that the minutiae of the current moment be mirrored in the archives, as our relationship with technology and distance change, and that we carry on with this work using the tools we have to get through these difficult times in the best way we know how. To illustrate how oral history and interview dynamics has evolved and adapted, what’s been lost and gained.

I’ve learned to lean more heavily on my pre-interviews, the conversations that I have with narrators in advance of the oral history sessions. These are generally meant to go over logistics, inform someone of their rights, go over topics and themes to address in the interview, and schedule sessions. While all of these usual rules still apply, I have become more sensitive to how this initial contact with them can build rapport from afar. I try to laugh more if I find something funny because they might not be able to see me smile. I’m more forthcoming about myself and the things we have in common because they might not be able to see me nod. I give them space to talk, still careful not to interrupt or cut them off, because they might not understand why I’m silent for a few beats during the interview. Above all, I don’t rush these calls. I talk my time getting to know them, answering their questions, and looking for ways to connect. I mail paperwork or email interview outlines when I say I will, using the little things I can control to build trust.

Remote interviewing may never be the same as sitting down face to face with someone, but rapport remains equally important. It’s in the relationships we build with our narrators that allow us to best honor their lives, making sure their legacy lives on long after they do, in their own words. Human connection means more now than ever before.

Shanna Farrell will be teaching about rapport and interviewing during our Advanced Oral History Institute, August 9–13. As last year, this year’s interactive institute is remote and draws attendees from all over the world.

Announcing Dates for 2021 OHC Educational Programs

The Oral History Center is pleased to announce that applications are now open for the 2021 Introductory Workshop and Advanced Institute!

The Introductory Workshop will held over two days on March 5-6, 2021.

The 2021 Introduction to Oral History Workshop will be held virtually via Zoom over two days on Friday, March 5, from 12–3 p.m. and Saturday, March, 6 from 9 a.m.–1.p.m. Pacific Time. Applications for this workshop are open here and will be accepted through February 16, 2021. Space is limited so apply early to ensure a spot.

will be held virtually via Zoom over two days on Friday, March 5, from 12–3 p.m. and Saturday, March, 6 from 9 a.m.–1.p.m. Pacific Time. Applications for this workshop are open here and will be accepted through February 16, 2021. Space is limited so apply early to ensure a spot.

The two-day day introductory workshop tuition is $200 and is designed for people who are interested in an introduction to the basic practice of oral history. The workshop serves as a companion to our more in-depth Advanced Oral History Summer Institute held in August.

This workshop focuses on the “nuts-and-bolts” of oral history, including methodology and ethics, practice, and recording. It will be taught by our seasoned oral historians and include hands-on practice exercises. Everyone is welcome to attend the workshop. Prior attendees have included community-based historians, teachers, genealogists, public historians, and students in college or graduate school.

The Advanced Institute will be held from August 9-13, 2021.

The OHC is offering an online version of our one-week advanced institute on the methodology, theory, and practice of oral history. This will take place via Zoom from August 9-13, 2021. Applications will be accepted through July 16, 2021. Apply now!

The cost of the Advanced Institute has been adjusted to reflect the online nature of this year’s program. This year’s cost has been adjusted to $550. See below for details about this year’s institute.

The institute is designed for graduate students, postdoctoral fellows, university faculty, independent scholars, and museum and community-based historians who are engaged in oral history work. The goal of the institute is to strengthen the ability of its participants to conduct research-focused interviews and to consider special characteristics of interviews as historical evidence in a rigorous academic environment.

We will devote particular attention to how oral history interviews can broaden and deepen historical interpretation situated within contemporary discussions of history, subjectivity, memory, and memoir.

Overview of the Week

The institute is structured around the life cycle of an interview. Each day will focus on a component of the interview, including foundational aspects of oral history, project conceptualization, the interview itself, analytic and interpretive strategies, and research presentation and dissemination.

Instruction will take place online from 8:30 a.m. – 12:30 p.m. Pacific Time, with breaks woven in. There will be three sessions a day: two seminar sessions and a workshop. Seminars will cover oral history theory, legal and ethical issues, project planning, oral history and the audience, anatomy of an interview, editing, fundraising, and analysis and presentation. During workshops, participants will work throughout the week in small groups, led by faculty, to develop and refine their projects.

Participants will be provided with a resource packet that includes a reader, contact information, and supplemental resources. These resources will be made available electronically prior to the Institute, along with the schedule.

Applications and Cost

The cost of the institute is $550. OHC is a soft money research office of the university, and as such receives precious little state funding. Therefore, it is necessary that this educational initiative be a self-funding program. Unfortunately, we are unable to provide financial assistance to participants. We encourage you to check in with your home institutions about financial assistance; in the past we have found that many programs have budgets to help underwrite some of the costs associated with attendance. We will provide receipts and certificates of completion as required for reimbursement.

Read Amanda Tewes’s recap of the 2020 session here.

Read Q&A with Institute Alums Julia Thomas, Alex Vassar, Alec O’Halloran, Kelly Navies, Meagan Gough, Nicole Ranganath, and Marc Robinson.

Questions?

Please contact Shanna Farrell at sfarrell@library.berkeley.edu with any questions.

Oral History Center Staff’s Top Moments of 2020

The year 2020 has been challenging and tumultuous. However, there have been bright spots as the Oral History Center transitioned to working remotely and conducting interviews over Zoom. We wanted to take a moment to reflect on what has brought us joy and given us strength as we leave 2020 behind.

Amanda Tewes, Interviewer/Historian:

This year has certainly created many challenges for me—as an interviewer and as a person—but I’ve been pleasantly surprised by the resiliency and creativity of my colleagues and the field of oral history as a whole. For example, Roger Eardley-Pryor and I worked with UC Berkeley undergraduate Miranda Jiang from 2019 through summer 2020. Miranda spent months researching and writing an original oral history performance for our 2020 Commencement, only to find that the pandemic had eliminated the potential for an in-person event. After regrouping, Miranda spent part of the summer transforming this performance intended for a live audience to a podcast episode on The Berkeley Remix (“Rice All the Time?”) complete with music and sound effects. This was not her original vision for the oral history performance, but she embraced the new media and its potential for reaching wider audiences, and is now working on an article about the challenges and benefits of this transition. We couldn’t be prouder!

Paul Burnett, Interviewer/Historian:

As a consequence of our adjustments to the COVID-19 pandemic, I realized more than ever that we all need to be better informed about the nature of epidemics and the social patterns that are revealed and exacerbated by them. With the help of our communications manager Jill Schlessinger and UDAR students Nika Esmailizadeh, Esther Khan, Corina Chen and Samantha Ready, we published curriculum content and frameworks for grade 11 students on epidemics in history. This curriculum makes use of our collection of interviews with those who confronted the AIDS epidemic in the early 1980s, along with our podcast on this subject. We are fundraising for a second round of interviews on the globalization of the HIV/AIDS pandemic, as well as a new project to develop curriculum materials on California communities and the environment based on our large collection of oral histories. Our collection is a fantastic resource for teachers, but we will continue to curate our content to make it easier to use in the classroom.

Roger Eardley-Pryor, Interviewer/Historian:

With silver bells ringing this holiday season, we search for silver linings amid the turmoil of 2020. My family’s continued health and safety remains that for which I’m most grateful, and both remain atop of our holiday wish list for you and yours. I’m also grateful and privileged to continue working at UC Berkeley’s Oral History Center (OHC). In the spring of 2018, when I began work at the OHC, my daughter was just 4 months old. This December of 2020, she turns three. Back in March of 2020, with heightened fear of the spreading pandemic and just as the Bay Area’s shelter-in-place orders came down, I corresponded with Dr. Samuel Barondes, a medically trained scientist at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) whose research bridged the fields of psychiatry and molecular neuroscience. Sheepishly, I told Sam my transition to working from home in a tiny one-bedroom apartment, which I shared with my wife and our rambunctious two-year old, would delay my work on his oral history that we recorded the prior year. Sam, now in his eighth decade of vibrant life, remembered well living in a one-bedroom apartment in New York City with his own high-energy two-year-old. Ever the optimist and exuding compassion, Sam told me, “Someday, you’ll treasure these memories of this momentous time…As always, everything is an opportunity!” At that time, I had a hard time hearing Sam’s wisdom. Now, having survived 2020, I understand. Nothing was easy this past year, but, already, I cherish my many months at home working while also watching our young daughter learn and grow. And, despite the past year’s chaos, I’m pleased to have finally published my lengthy oral history interviews with Alexis T. Bell, a professor in the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering in UC Berkeley’s College of Chemistry; with Michael Schilling, a chemist and head of Materials Characterization at the Getty Conservation Institute (GCI) in Los Angeles; and with Aaron Mair, a pioneer of environmental justice and the first Black president of the Sierra Club. In the coming year, I look forward to COVID vaccines, a new US President, and to completing additional oral histories long delayed by the pandemic, including Dr. Sam Barondes’s. I miss the intimacy and comradery of in-person meetings, of handshakes and hugs, of shared stories and raw laughter reverberating in a room, not filtered through a silicon chip. I hope to see you on the other side of this pandemic. From my family to all of yours, we wish you a happy, safe, and healthy holiday season, and may you know peace and justice in the new year.

Jill Schlessinger, Communications Manager/Managing Editor:

There were many highlights this year in the areas of communications, oral history production, and process. It’s wonderful to work with my team of student editors, Ashley Sangyou Kim, JD Mireles, Jordan Harris, Lauren Sheehan-Clark, and Ricky Noel; communications assistant Katherine Chen, and research assistant Deborah Qu, and I want to thank them for their high-quality work and professionalism. The editorial team wrote discursive tables of contents and edited frontmatter and interviews for dozens of oral histories this year, among other projects. We contributed to the Berkeley Women 150 celebrations, including a collection guide to 225 oral histories with UC Berkeley women — alumnae, faculty, staff, administrators, and philanthropists; a Berkeley women oral history web page, and four articles highlighting the achievements of Berkeley women by our undergraduate research assistant Deborah Qu, about alumnae Janet Daijogo and Ida Louise Jackson, faculty Natalie Zemon Davis and Elizabeth Malozemoff, and Berkeley’s first dean of women, Lucy Sprague Mitchell. I launched a new project management tool to track our complex production process, with more than 100 steps, and our many other initiatives, making collaboration and tracking easier. The Smithsonian Magazine, KPIX-CBS, NPR, East Bay Yesterday podcast, the San Francisco Chronicle, and the movie, Crip Camp, winner of the Audience Prize for documentary at the Sundance Film Festival, among others, featured our oral histories or interviews with our historians/interviewers. A personal highlight for me was writing the article “Never Forget? UC Berkeley’s Oral History Center documents memories of the Holocaust for researchers and the public,” in observance of the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz.

Todd Holmes, Interview/Historian:

One of my fondest memories this year at the OHC was our Advanced Summer Institute. Each year we host over 50 participants during this week-long event, teaching the ins and outs of oral history and helping the wide-range of attendees in developing their individual projects. Like so many activities on the Berkeley campus, however, Covid-19 forced us to come up with a safer alternative. Thanks to Shanna Farrell—the office’s longtime Advanced Summer Institute coordinator—we held the institute via Zoom with minimal bumps along the road, allowing us to connect with participants from around the world. Indeed, it was not uncommon to have participants from 3 or 4 different time zones in one meeting. It was an amazing experience, one that highlighted our interconnectedness, as well as what can be achieved with technology and teamwork.

Shanna Farrell, Interview/Historian:

This year has been a doozy. When the shelter-in-place order hit in March, we had to re-learn how to structure our days and focus on work while the world crumbled around us. Many of our projects paused while we collectively tried to regroup and design a path forward. To call this difficult, especially while constantly refreshing my newsfeed, is an understatement. So, I turned to one of my great loves: audio. We launched a series of special episodes of our podcast, The Berkeley Remix, called “Coronavirus Relief.” The intention was to bring stories from the field of oral history, things that had been on our mind, lessons from the past, and interviews that helped us get through, to find small moments of happiness. I served as the producer and editor of these episodes, even writing my own episodes, and worked with Amanda Tewes and Roger Eardley-Pryor, proving that remote collaboration was still possible. Making these seven episodes of The Berkeley Remix was one of my favorite parts of 2020, as it allowed me stay connected to my colleagues, gave me space to think about the value of oral history, and engage our audience during dark days.

Martin Meeker, Director:

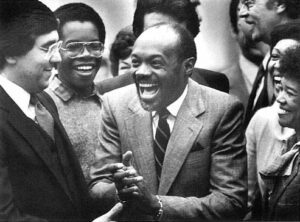

Before joining the Oral History Center in 2003 as a postdoc, I had already read the Center’s interview with Willie Brown about his years as Speaker of the California Assembly. I held this up as the pinnacle of political oral history and resolved that one day I would conduct a follow-up and ask him about his two terms as San Francisco Mayor. In 2015 and 2016 the opportunity arose and I conducted a 10 hour oral history with Mayor Brown and I was thrilled with the results. And, finally, in 2020 the mayor gave his blessing for us to release this second volume of what is now a thorough and fascinating life history.

The Oral History Center Plans to Launch New Project on Contact Tracing

The COVID-19 crisis has ushered in a new era of world history, and continues to have a profound impact on daily life around the world, including the Bay Area. But the fight against this global pandemic also includes a regional public health tool: contact tracing. News outlets and public health officials often say that manual contact tracing is key to protecting the community.

The Oral History Center hopes to launch a project about contact tracing that will document the historic nature of the work, as well as evaluate its effectiveness in this moment as it relates to public health, community, and politics.

Interested in helping to make this project a reality? We are now accepting tax-deductible donations!

Contact tracing, the process of charting the chain of infection to control transmission, has been practiced since the 1930s. It first played a key role in reducing the spread of syphilis among U.S. troops during World War II. Later, public health advisers, referred to as P.H.A.s, used this strategy to control tuberculosis, smallpox, and the 2009 H1N1 Pandemic. Early P.H.A.s were required to have a college degree, preferably in liberal arts, with a variety of work experience that gave them enough emotional intelligence to form connections with anyone from business executives to rural farmers. P.H.A.s have been incredibly successful in reducing the spread of disease and infection, and were responsible for blowing the whistle on the Tuskegee experiment.

The process has shifted since then, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, and experts often cite contact tracing as the key to mitigating the spread of the coronavirus. Job requirements are different, and in San Francisco, furloughed city employees––like librarians, city attorneys, and tax assessors––are filling these roles previously held exclusively by P.H.A.s.

As the COVID-19 crisis continues to reshape all facets of life, it is essential to explore the experiences of public health experts and contact tracers in real time. The OHC hopes to record and archive oral history interviews with contact tracers and others who are fighting COVID-19 by planning health policy, analyzing data, and tracking the human toll of the outbreak. In-depth topical interviews about tracking the spread of the virus will document the current moment and the intensive human work of manual contact tracing.

Help us make this project a reality by making a tax-deductible donation here.

*Note: Please check “This Gift is in the Honor or Memory of Someone” when you make your donation. Please write “Contact” for the first name, and “Tracing” for the last name fields.

Thank you for supporting our work!

Interested in learning more? Contact Shanna Farrell (sfarrell@library.berkeley.edu) or Amanda Tewes (atewes@berkeley.edu).

OHC at the Oral History Association Conference

As with most things this year, the 2020 Oral History Association conference will be held digitally. The theme, “The Quest for Democracy: One Hundred Years of Struggle,” was inspired by the Centennial of the 19th Amendment, which granted women the right to vote, yet excluded Black men and women in the Jim Crow South. In choosing this theme, we hoped to encourage submissions that interrogate the idea of “Democracy,” its inherent assumptions and challenges; submissions of oral history projects that illuminate the ways in which we participate in democracy, who has access to the political process and who has historically struggled to gain such access.

OHC’s own Shanna Farrell and the Smithsonian’s Kelly Navies (who is one of our Advanced Summer Institute alumni!) served as the conference co-chairs and are very excited to kick off what promises to be an engaging and dynamic week of presentations.

If you’re attending next week, we’d love for you to check out sessions from the OHC staff. Here’s the lineup:

- Monday, October 19:

- Amanda Tewes leading “An Oral Historian’s Guide to Public History” workshop from 11am – 2:30pm ET/8 – 11:30am PT

- Wednesday, October 21:

- Paul Burnett will be on the “Educating in High School and University Involves Listening” panel talking about UC Berkeley OHC K16 Outreach Project: The HIV/AIDS Curriculum Pilot at 3:30pm ET/12:30 PT

- Shanna Farrell will be chairing the “Oral History for an Audience: Podcasts, Performance, and Documentaries” session at 3:30pm ET/12:30 PT

- Thursday, October 22:

- Roger Eardley-Pryor will be talking to OHC narrator Aaron Mair for the “Hitched to Everything: Aaron Mair, Environmental Justice, and the Sierra Club” session that will be chaired by Shanna Farrell at 3:30pm ET/12:30 PT

We hope to “see” you there!

The Value of Open Space

The Bay Area is beautiful. Its myriad of picturesque beaches, mountains, woods, and lakes is a big part of why it’s such a desirable place to live. And since March, when the California shelter-in-place order was issued to slow the spread of the coronavirus pandemic, the value of these outdoor spaces has never been more clear.

The East Bay Regional Park District has worked to preserve open space since its founding in 1934. Over the years, it has acquired 125,000 acres of land, which spans 73 parks. The public access to nature that the concert of parks provide adds to quality of life here, especially with the parks’ proximity to urban areas (which is detailed in Season 5 of The Berkeley Remix podcast, Hidden Heroes).

There are many people in the district’s network, both those who make up the workforce and those who help it thrive in other ways, like documenting its history, selling their land to them, and advocating for its mission. Since 2017, I’ve had the pleasure of leading the East Bay Regional Park District Parkland Oral History Project, for which I have the opportunity to record the stories of the people who make the district special.

This past year, I interviewed ranchers, activists, a maintenance worker, an artist, the daughter of a historian, and a park planner, all of whom had unique perspectives to share about the legacy of the district. Here are the ways in which each of their stories speak to the value of preserving open space:

Diane Lando grew up in the East Bay on a ranch. She became a writer, drawing inspiration from her childhood. As the Brentwood Poet Laureate, she published The Brentwood Chronicles, which consists of two books. These books express just how important growing up on the ranch had been for her, giving her a sense of independence and self.

Raili Glenn immigrated to the United States from Finland and settled in California as a newly married woman. She had a successful career in real estate and she and her late husband bought a house in Las Trampas, which is now owned by the EBRPD. This house meant a great deal to her —it’s beauty, quiet, and charm helped her find home in the parks.

Roy Peach grew up in the East Bay, spending much of his childhood in Sibley Quarry, which is now owned by the park. Growing up here, he learned about the environment, geology, and himself as he spent as much time as he could outdoors. His love of nature has followed him into adulthood, and camping has continued to be an important pastime.

Ron Batteate is a fourth generation rancher. He grew up in the East Bay, following in the footsteps of the men who came before him. He leases land from the district where he grazes his cattle. His love for open space and his livestock runs deep, evident in the way he talks about the importance of understanding nature with commitment and passion. If I were a cow, I’d want to be in Ron’s herd.

Janet Wright grew up in Kensington with parents who were very involved with their community. Her father, Louis Stein, was a pharmacist by day and a local historian by night. He collected artifacts from around town, which proved to be important in the documentation of local history. The maps, photos, letters, newspapers, ephemera — and horse carriage — that he collected are now archived at both the History Center in Pleasant Hill and with the Contra Costa Historical Society. These materials help tell the story of the importance of the district in many people’s lives.

Glenn Adams is the nephew of Wesley Adams, the district’s first field employee. Wesley was hired in 1937 and had a long career with the district, retiring after decades of service. Glenn fondly remembers his uncle Wes, who he says shaped his life greatly, including passing along his passion for the parks. Glenn has in turn shared his love of the outdoors with his family, who continue to use the parks today.

Mary Lenztner grew up on a ranch in Deer Valley that her parents, who both immigrated from the Azores, bought in 1935. She moved to San Jose with her mother after her father’s death, but returned to the area later as an adult. As her children got older, she became curious about her family’s ranching legacy. She learned about raising cattle, and went on to take over her family’s ranch. She lived there, raising cattle and other livestock, for 25 years before selling it to the district. Her relationship with this land helped her connect with her family and their past, and her interview drives home the importance of place in our lives.

Bev Marshall and Kathy Gleason live in Concord near the Naval Weapon Stations, part of which is now owned by the district . When they were deactivating the base, they both fought to keep it open space. Their work helped them form a lifelong friendship, find community, and a voice in local politics, while successfully limiting development in the area.

Rev. Diana McDaniel is a reverend in Oakland and is the President of Board for the Friends of Port Chicago. She has long been active in educating the public about the Port Chicago tragedy, which her uncle was involved in. She works with the district (and National Park Service) to make sure the story of what happened at Port Chicago isn’t forgotten. Her story illustrates how important parks are not just for open space, but for public history, too.

John Lytle was a maintenance worker at the Concord Naval Weapons Station where he specialized in technology. He found fulfillment in his work there over the years, and his interview demonstrates the careful planning that goes into transitioning a naval base into a public park.

Brian Holt is a longtime EBPRD employee who currently serves as a Chief Planner. He has been involved in many of the district’s initiatives, including acquiring much of its land. He works with community members, trying to understand issues from different perspectives. He cultivates understanding of the nuances of each issue, ultimately informing the district’s involvement in preserving open space.

All of these narrators demonstrate just how important the district is to preserving public space, especially space that is accessible to everyone. Each person illustrates the power the parks and the communities that spring up within them, which is more important than ever during these tumultuous times.

This year, I interviewed:

Diane Lando

Raili Glenn

Glenn Adams

Roy Peach

Mary Lentzner

Beverly Marshall

Kathy Gleason

Janet Wright

Ron Batteate

John Lytle

Brian Holt

Reverend Diana McDaniel

And

Melvin Edwards

Peter Bradley

Both for the GRI African American Artist Initiative, outlined in Amanda Tewes’ blog post

Episode 6 of the Oral History Center’s Special Season of the “Berkeley Remix” Podcast

Shanna Farrell:

Hello and welcome to The Berkeley Remix, a podcast from the Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley. Founded in 1954, the Center records and preserves the history of California, the nation, and our interconnected world.

Lately, things have been challenging and uncertain. We’re enduring an order to shelter-in-place, trying to read the news, but not too much, and prioritize self-care. Like many of you, we’re in need of some relief.

So, we’d like to provide you with some. Episodes in this series, which we’re calling “Coronavirus Relief,” may sound different from those we’ve produced in the past, that tell narrative stories drawing from our collection of oral histories. But like many of you, we at the Oral History Center are in need of a break.

We’ll be adding some new episodes in this Coronavirus Relief series with stories from the field, things that have been on our mind, interviews that have been helping us get through, and find small moments of happiness.

Amanda Tewes:

Hello, everyone! This is Amanda Tewes.

I was an avid podcast listener even before we all started sheltering in place. These days I’ve doubled down. But instead of listening on my commute, I catch up with episodes during my daily walks. And I’ve been sharing some of my favorite podcasts dealing with history, memory, and archival audio on the Oral History Center blog.

Today I’m going to tell you about a new podcast I’ve been listening to called Wind of Change, which was recently featured on the blog. You’re going to want to buckle up for this wild ride.

German heavy metal meets Cold War intrigue. If you’re looking for a fun listen during shelter-in-place, I highly recommend the podcast Wind of Change!

Following a rumor that the German band the Scorpions’ 1990 hit song “Wind of Change” was actually written by the CIA as Cold War propaganda, investigative reporter Patrick Radden Keefe turned this long-form piece into an eight-part podcast series documenting the song’s influence on politics and popular culture, as well as its potential connection to American clandestine operations. Throughout, Keefe toys with the tension as to whether or not this kind of CIA involvement in songwriting is likely. After listening, my takeaway is that it’s just wild enough to be true.

Many Americans haven’t even heard of the Scorpions. And if you’ve heard of them at all, it’s due to their song “Rock You Like a Hurricane.” You know the one.

But this German band that sings in English has diehard fans all over Europe and Asia. Formed in 1965 in Hanover, Germany, three of the five band members have been playing together since 1978. And they continue to tour internationally.

And what makes the song “Wind of Change” so fascinating is its resonance with the zeitgeist of 1990. The song was supposedly written after the band played in Moscow in 1989 and was released shortly after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

For many, the song represents the “change” happening across Europe that led to the collapse of the Soviet Union. But as Keefe points out, “Wind of Change” isn’t just the soundtrack to the end of the Cold War, but also a song with modern resonance. When he saw the Scorpions live in Kiev, Ukraine, alongside huge crowds, Keefe was reminded that the country was actually still at war with Russia, trying to maintain its post-Cold War independence.

For Ukranians at least, “Wind of Change” is not just nostalgia, but a sort of call to arms.

Keefe’s previous work inlcudes his 2019 book Say Nothing: The True Story of Murder and Memory in Northern Ireland, which the Oral History Center chose as its inaugural book club pick. (Make sure to check out that conversation!) In Say Nothing, Keefe explores the challenges of The Troubles in Northern Ireland, alongside the murder of Jean McConville and the Boston College Belfast Project oral histories. In Wind of Change, Keefe encounters similar challenges working with former spies as he did with former revolutionaries in Ireland: lies and obfuscation.

The delight of listening to this story in a podcast format is the ability to hear the song itself, the enthusiasm from live Scorpions audiences, archival and new interviews, and to provide some (but not enough for their taste) anonymity for former clandestine officers. But Wind of Change offers more than just great audio, it also takes the listener on a journey into how to investigate a thirty-year-old story, following oddball leads – even to a G.I. Joe convention – and invites skepticism about what information to actually believe. Indeed, the podcast also questions the nature of storytelling around this rumor and its own role in continuing the myth making around the CIA. But Keefe also wonders: how do you uncover something that (if true) was among the top CIA secrets during the Cold War? As an oral historian, I would add that these events have also been diluted by memory and time, and those who can speak to the true origins of “Wind of Change” may no longer be able to do so.

Part cultural history and part investigation into Cold War operation, Wind of Change also documents the CIA’s other attempts at cultural influence. From Louis Armstrong to Nina Simone to Doctor Zhivago, Keefe reiterates the CIA’s long history of using popular culture to convey the principles of Western democracy and undermine communism. Further, Keefe points to the very nature of rock and roll as ripe for use as propaganda: the genre was effectively banned in the USSR, so the act of listening to the music itself was a proxy for political rebellion.

The podcast Wind of Change is not just a fun listen about a campy band and Cold War CIA operations, but also a compelling story and a great distraction. Listen to all eight episodes of Wind of Change right now on Spotify.

You’ve got the song stuck in your head now, don’t you?

Stay safe, everyone. Until next time!

Farrell:

Thanks for listening to The Berkeley Remix. We’ll catch up with you next time. And in the meantime, from all of us here at the Oral History Center, we wish you our best.

This episode includes music by the Scorpions and Paul Burnett.

Episode 5 of the Oral History Center’s Special Season of the “Berkeley Remix” Podcast

Lately, things have been challenging and uncertain. We’re enduring an order to shelter-in-place, trying to read the news, but not too much, and prioritize self-care. Like many of you, we here at the Oral History Center are in need of some relief.

So, we’d like to provide you with some. Episodes in this series, which we’re calling “Coronavirus Relief,” may sound different from those we’ve produced in the past, that tell narrative stories drawing from our collection of oral histories. But like many of you, we, too, are in need of a break.

The Berkeley Remix, a podcast from the Oral History Center of the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley. Founded in 1954, the Center records and preserves the history of California, the nation, and our interconnected world.

We’ll be adding some new episodes in this Coronavirus Relief series with stories from the field, things that have been on our mind, interviews that have been helping us get through, and finding small moments of happiness.

Our fifth episode is from Shanna Farrell.

When the shelter-in-place order was issued in mid-March by California Governor Gavin Newsom, many thoughts ran through my head. One of the milder ones — the kind that comes from the part of me that tries to find a silver lining in bad situations — was that I might have more time to read. I’ve always been an avid reader, mostly of fiction and narrative non-fiction, and often find myself counting down the hours until I can return to my book.

But in those early days of the global COVID-19 pandemic, I couldn’t concentrate on many things other than the news. My working hours bled into my free time as I tried my best to knock projects off my to-do list and remain productive as the world crumbled around us.

And then one day I found myself staring at my bookshelf, the myriad of colorful spines calling to me. A soft pink cover caught my eye. I pulled Severance, a post-apocalyptic book by Ling Ma, off the shelf and cracked it open. The novel follows Candace Chen as a flu pandemic hits modern-day New York City. I call New York home, so it hit close, and was strangely cathartic. It didn’t hurt that the book is beautifully written and Ma’s prose is absorbing. It allowed me to escape in a way that worked with my limited focus.

Back in the groove, I next read Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel, another post-apocalyptic novel about a global flu pandemic. This one split the timeline between when the pandemic hit Toronto, Canada, and twenty years in the future. In it, the author uses oral history as a device to connect the timelines. Every time I encounter the term “oral history” in literature – be it fiction or non-fiction – my heart quickens, never knowing if it’s being misused.

As I read the fictional oral history interview transcript interspersed throughout the second half of Station Eleven, I was delighted, and deeply impressed, that Mandel seemed to understand that oral history is a type of long-form, recorded interview. This deepened my appreciation for both the writer and the book, discovering that there are people out there who don’t blur the lines between a clearly-defined methodology (about which I’ve mused on the OHC’s blog), taking the time to do their due diligence before employing a term they’ve heard about in passing.

Ever since I read World War Z: An Oral History of the Zombie Apocalypse by Max Brooks, I’ve loved when authors use fictional oral history interviews to tell a story. I find the interviewer and narrator exchange, the chorus of voices, and the details from the past an engaging way to draw the reader in. Many times, I feel like I’m in the room with them.

My colleague, Amanda Tewes agrees. “I like that the familiarity of oral history draws me into a story (almost as if it was real) and allows the author to toy with memory in a way that is difficult when juggling many characters,” she’s told me.

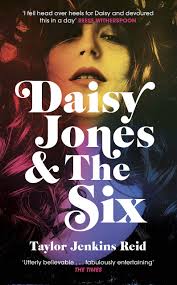

This brings us to our next OHC Oral History Book Club selection, picked by Amanda, which embraces the trend of oral history as a literary device in fiction. We’ll be reading Daisy Jones & the Six, by Taylor Jenkins Reid, which the New York Times calls “a gripping novel about the whirlwind rise of an iconic 1970s rock group and their beautiful lead singer, revealing the mystery behind their infamous breakup.”

The story unfolds through a series of fictional oral histories. The format is the kind we often find on the pages of Entertainment Weekly or Vanity Fair, inspired by the hallmark oral history book Edie about Edie Sedgewick. Daisy Jones & the Six is a best-seller, a Reese Witherspoon Book Club pick, and is the basis for a new mini-series from Witherspoon’s production company.

This time around, we’re inviting you to join us for the June installment of our book club. On June 15, we’ll be holding a virtual meeting. We’ll be discussing the book, the use of oral history in literature and pop culture, and more. Please join us for a bit of escape during these deeply difficult, challenging times.

We’ll be meeting on Zoom on Monday, June 15 at 11am PST/2pm EST. Please send me, Shanna Farrell, as RSVP via email if you’d like to join us. My email is sfarrell@library.berkeley.edu, which you can also find on the OHC’s website.

Until then, happy reading and stay safe!

You’re Invited to the Summer Edition of the OHC Book Club

Oral History, Literature, and the June OHC Book Club Selection

When the shelter-in-place order was issued in mid-March by California Governor Gavin Newsom, many thoughts ran through my head. One of the milder ones — the kind that comes from the part of me that tries to find a silver lining in bad situations — was that I might have more time to read. I’ve always been an avid reader, mostly of fiction and narrative non-fiction, and often find myself counting down the hours until I can return to my book.

But in those early days of the global COVID-19 pandemic, I couldn’t concentrate on many things other than the news. My working hours bled into my free time as I tried my best to knock projects off my to-do list and remain productive as the world crumbled around us.

And then one day I found myself staring at my bookshelf, the myriad of colorful spines calling to me. A soft pink cover caught my eye. I pulled Severance, a post-apocalyptic book by Ling Ma, off the shelf and cracked it open. The novel follows Candace Chen as a flu pandemic hits modern-day New York City. As a native New Yorker, It hit close to home, and was strangely cathartic. (It didn’t hurt that the book is beautifully written and Ma’s prose was absorbing.) It allowed me to escape in a way that was right for the limits of my focus at the time.

Next I read Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel, another post-apocalyptic novel about a global flu pandemic. This one split the timeline between when the pandemic hit Toronto, Canada, and twenty years in the future. In it, the author uses oral history as a device to connect the timelines. Every time I encounter the term “oral history” in literature – be it fiction or non-fiction – my heart quickens, never knowing if it’s being misused.

As I read the fictional oral history interview transcript interspersed throughout the second half of Station Eleven, I was delighted, and deeply impressed, that Mandel seemed to understand that oral history is a type of long-form, recorded interview. This deepened my appreciation for both the writer and the book, discovering that there are people out there who don’t blur the lines between a clearly-defined methodology (about which I’ve mused on this very blog), taking the time to do their due diligence before employing a term they’ve heard about in passing.

Ever since I read World War Z: An Oral History of the Zombie Apocalypse by Max Brooks, I’ve loved when authors use fictional oral history interviews to tell a story. I find the interviewer and narrator exchange, the chorus of voices, and the details from the past an engaging way to draw the reader in. Many times, I feel like I’m in the room with them.

My colleague, Amanda Tewes agrees. “I like that the familiarity of oral history draws me into a story (almost as if it was real) and allows the author to toy with memory in a way that is difficult when juggling many characters,” she says.

This brings us to our next OHC Oral History Book Club selection, picked by Tewes, which embraces the trend of oral history as a literary device in fiction. We’ll be reading Daisy Jones & the Six, by Taylor Jenkins Reid, which the New York Times calls “a gripping novel about the whirlwind rise of an iconic 1970s rock group and their beautiful lead singer, revealing the mystery behind their infamous breakup.”

The story unfolds through a series of fictional oral histories. The format is the kind we often find on the pages of Entertainment Weekly or Vanity Fair, inspired by the hallmark oral history book Edie about Edie Sedgewick. The book is a best-seller, a Reese Witherspoon Book Club pick, and is the basis for a new mini-series from Witherspoon’s production company.

We’re inviting you to join us for the June installment of our book club. On June 15, we’ll be holding a virtual meeting. We’ll be discussing the book, the use of oral history in literature and pop culture, and more.

RSVP to sfarrell@library.berkeley.edu if you’d like to join us for our book club via Zoom on Monday, June 15 at 11am PST/2pm EST.

Until then, happy reading and stay safe!

Episode 4 of the Oral History Center’s Special Season of the “Berkeley Remix” Podcast

Lately, things have been challenging and uncertain. We’re enduring an order to shelter-in-place, trying to read the news, but not too much, and prioritize self-care. Like many of you, we here at the Oral History Center are in need of some relief.

So, we’d like to provide you with some. Episodes in this series, which we’re calling “Coronavirus Relief,” may sound different from those we’ve produced in the past, that tell narrative stories drawing from our collection of oral histories. But like many of you, we, too, are in need of a break.

The Berkeley Remix, a podcast from the Oral History Center of the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley. Founded in 1954, the Center records and preserves the history of California, the nation, and our interconnected world.

We’ll be adding some new episodes in this Coronavirus Relief series with stories from the field, things that have been on our mind, interviews that have been helping us get through, and finding small moments of happiness.

Our fourth episode is from Roger Eardley-Pryor.

This is Roger Eardley-Pryor. I’m am an interviewer and historian of science, technology, and the environment at Berkeley’s Oral History Center. For this episode of Coronavirus Relief, I want to share stories with you about the very first Earth Day in 1970, which just celebrated its 50th anniversary.

Mercy, mercy me! Earth Day turned 50 in April 2020. A half-century ago, on April 22, 1970, environmental awareness and concern exploded in a nationwide outpouring of celebrations and protests during the world’s first Earth Day. That first Earth Day drew an estimated twenty million participants across the United States—roughly a tenth of the national population—with involvement from over ten thousand schools and two thousand colleges and universities. That first Earth Day, on April 22, became the then-largest single-day public protest in U.S. history. The actual numbers of participants were even higher. Several universities, notably the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, organized massive Earth Day teach-ins, some of which they held in the weeks before April 22nd to avoid overlapping with their final exams. From New York City to San Francisco, from Cincinnati to Santa Barbara, from Birmingham to Ann Arbor—millions of Americans gathered on campuses, met in classrooms, visited parks and public lands together, participated in local clean-ups, and marched in the streets for greater environmental awareness and to demand greater environmental protections. Even Wisconsin Senator Gaylord Nelson was surprised. And it was Senator Nelson who, in the fall of 1969, first promoted the idea for nation-wide teach-ins about the environment. He called Earth Day in 1970 a “truly astonishing grass-roots explosion.” In the fifty-years since, Earth Day events have spread globally to nearly 200 nations, making it the world’s largest secular holiday celebrated by more than a billion people each year.

But this past April, despite years of planning for Earth Day’s fiftieth anniversary, the novel coronavirus—itself a world-wide environmental event—disrupted Earth Day 2020 plans across the planet. We were not able to celebrate Earth Day’s golden anniversary as previously planned. Instead, we can commemorate it with recollections—and lessons learned—by those who attended and organized the first Earth Day events in 1970. The Oral History Center’s archives list over seventy interviews that mention Earth Day.

I’ve selected here a few memories of the first Earth Day from our Sierra Club Oral History Project, a collaboration between the Sierra Club and Berkeley’s Oral History Center, that was initiated soon after that first Earth Day. These Earth Day memories from Sierra Club members begin with experiences in the streets of New York City, they include memories at the forefront of environmental law, and they conclude with a Sierra Club member who was inspired to activism at the University of Michigan’s first-ever Earth Day teach-in.

We’ll begin with Michele Perrault, who in the 1980s and 1990s was twice elected as president of the Sierra Club. Back in 1970, Michele Perrault lived and worked in New York City as an elementary-school science teacher. New York City was the site the nation’s largest celebrations of Earth Day, which captured nationwide media attention given that NBC, CBS, ABC, The New York Times, Newsweek, and Time Magazine were all headquartered in Manhattan. Perrault, who was then twenty-eight years old, taught in the demonstration school at the Bank Street College of Education. Bank Street College was founded more than 50 years earlier, in 1916, by a women named Lucy Sprague Mitchell, a child education reformer and, before that, Berkeley’s first Dean of Women. The Oral History Center has a great interview with her, too. But back to Michele Perrault.

For her part, Perrault told me—during her oral history—how she organized “a Bank Street program out in the street for Earth Day in New York City.” … “we had our own booth, and I had the kids there … Mostly we sang songs and danced around and had some visuals and books that people could read or get, and we had some pamphlets from the [Bank Street] College that talked about it.” In the process, Perrault and her students joined hundreds of thousands of other Earth Day participants in the streets of Manhattan. John Lindsay, the Republican mayor of New York, had closed traffic on Fifth Avenue for Earth Day, and he made Central Park available for gigantic crowds to march and celebrate together. The New York Times estimated over 100,000 people visited New York’s Union Square throughout Earth Day.

Earlier in 1970, Michele Perrault joined student teachers to plan Earth Day teach-ins in New York. That’s when Perrault met René Dubos—a famous microbiologist, an optimistic environmentalist, and a Pulitzer-Prize-winning author who first coined the phrase “Think Globally, Act Locally.” At that time, Michele Perrault served as education chair for the Sierra Club’s Atlantic Chapter in New York, for whom she had recently started a newsletter called Right Now!—a monthly publication full of ideas for environmental educators. Two copies of Right Now! are included in the appendix to Michele Perrault’s printed oral history, which is available online, like all of the Oral History Center’s interviews. In one edition of Right Now!, Perrault recalled René Dubos’s advice for the upcoming first Earth Day.

Dubos “stressed the importance and need for people to take time to reevaluate what is needed for quality of life, to sift and sort alternatives—perhaps not in existence now, to look in a new way at what the future could be like, and then devise plans for making it so.” Perrault added this: “We, as teachers, need to ask new questions about our own values, about our own social and economic systems and their relationship to the environment, so as to enrich the present and potential environment for children.”

In 1971, less than a year after Earth Day, Perrault organized at Bank Street College an education conference titled “Environment and Children.” She invited René Dubos as the keynote speaker, and she remembered: Dubos called for stimulating environments for children that offered “the ability to choose, to have variety, to not just be in one place where everything was static around them and where they weren’t in control. [He] had a big paper on this whole issue of free will and being able to make choices, and how the environment would influence them.” Years later, after moving to California, Perrault took her own children on annual backpacking trips deep into the High Sierra Nevada mountains where they could run wild and free, stimulated by natural wilderness.

Michele Perrault was recruited to the Sierra Club shortly before Earth Day by a guy named David Sive, a pioneer of environmental law in New York, whose children Perrault taught in her science classroom. The Sierra Club Oral History Project includes a great interview with David Sive from 1982. Another Sierra Club member and trailblazer of environmental law is James Moorman, Moorman shared his own memories of the first Earth Day during his oral history in 1984. Back in 1970, Moorman had then recently joined the newly created Center for Law and Social Policy, or CLASP. CLASP is an influential public-interest law firm in Washington, DC. In the late 1960s, Jim Moorman was a young trial lawyer who brought two cases that became landmarks in environmental law. The first was a petition to the US Department of Agriculture to de-register the pesticide DDT. The second was a suit against the US Department of the Interior challenging construction of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline. For the pipeline case, Moorman pioneered use of the National Environmental Policy Act (or NEPA), which had just been enacted in January 1970. Based on NEPA, Moorman demanded from the Interior Department a detailed Environmental Impact Statement for the pipeline project.

Moorman recalled: “the preliminary injunction hearing for the Trans-Alaska Pipeline was originally set for Earth Day. … when the judge first set the hearing, I said, ‘Holy cow! He set the hearing for this on Earth Day and he doesn’t know it, and the oil companies don’t know it. I’m going to get to make my argument on Earth Day. That’s fantastic!’ But then there was a postponement, and the argument didn’t occur until two weeks later. But it was wonderful anyway.” Jim Moorman won his case. But Congress directly intervened to approve the pipeline by law. Nonetheless, Moorman’s injunction forced the oil companies to spend more than three years and a small fortune on engineering, analysis, and documentation for the project. The final Environmental Impact Statement for the Trans-Alaska Pipeline stretched to nine volumes! Moorman’s legal intervention helped produce a safer pipeline that, today, is still considered a wonder of engineering.

In the year following the first Earth Day, Moorman accepted a new job as the founding Executive Director of the Sierra Club Legal Defense Fund, now known as Earthjustice. It was one of the nation’s earliest and remains one of the most influential public-interest environmental law organizations. Moorman directed the Sierra Club Legal Defense Fund through 1974, and he worked as a staff attorney with the organization through 1977. That was when he became Assistant Attorney General for Land and Natural Resources under President Jimmy Carter. But in his 1984 oral history, Jim Moorman reflected on the importance of the first Earth Day for environmental law: “The fact is Earth Day came rather early in all this [environmental law] movement. We’ve been living on the energy created by Earth Day ever since.” Mike McCloskey—also a lawyer—couldn’t agree more.

Back in 1970, Mike McCloskey was still getting used to his new his role as Executive Director of the Sierra Club, a position McCloskey took up in the wake of David Brower and held through 1985. In the first of Mike McCloskey’s two oral histories—that first one from 1981—McCloskey recalled the Earth-Day-era as “a very exciting time in terms of developing new theories [of environmental law]. Our spirits were charged up. The courts were anxious to make law in the field of the environment. There were judges who were reading, and they were stimulated by the prospect. They were eager to get environmental cases.”… “what became clear over the next few years [after Earth Day] were that dozens of, if not hundreds, of laws were passed and agencies brought into existence.” He’s right. A few months after the first Earth Day, President Nixon established the Environmental Protection Agency. Over the next few years, Congress passed a suite of landmark environmental statutes—including an amended Clean Air Act; the Clean Water Act; the Safe Drinking Water Act; the Endangered Species Act; the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act; the Toxic Substances and Control Act and many others … all of which—thus far—have avoided extinction.

Mike McCloskey remembered the first Earth Day in 1970 as an explosion of the environmental consciousness that had grown steadily throughout the late 1960s. In 1968, not long before Earth Day, conservationists like McCloskey thought the best of times had already happened. The creation of Redwood National Park in California, North Cascades National Park in Washington state, and the passage of both the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act and the National Trails System Act, all occurred in that revolutionary year of 1968. McCloskey recalled, “We, at that moment, thought this was some high point in conservation history and wondered whether much would happen thereafter.” In January 1969, President Richard Nixon came into office. McCloskey and other Sierra Club leaders remembered: we felt “very defensive and threatened, not realizing that we were on a threshold of an explosion into a period of our greatest growth and influence.” By 1970, instead of a plateau or even a decline in environmental efforts, Sierra Club leaders saw the American environmental movement experience what McCloskey described as “a tremendous take-off in terms of the overall quantity of activity, enthusiasm, and support with Earth Day. … it was just an eruption of activity on every front.”

But much to his surprise, with Earth Day in 1970, McCloskey also saw how many traditional leaders of the conservation movement were quickly regarded as “old hat and out of step with the times.” In their place, he witnessed how people “emerged at the student level, literally from nowhere, who were inventing new standards for what was right and what should be done and whole new theories overnight. For instance, I remember hostesses who were suddenly saying, ‘I can’t serve paper napkins anymore. I’ve got to have cloth napkins.’ Someone had written that paper napkins were terribly wrong—and colored toilet paper was regarded as a sin. But all sorts of people from different backgrounds coalesced in the environmental movement. People who were interested in public health suddenly emerged and very strongly.” One such person was Doris Cellarius.

In 1970, Doris Cellarius lived in Ann Arbor, Michigan, with her children and husband, Dick Cellarius, a professor of botany who was then teaching at the University of Michigan. According to Doris, she and Dick were both members of the Sierra Club in 1970, but mostly for hiking and social engagement, less for activism. The extraordinary events surrounding Earth Day in Ann Arbor changed everything. As Doris explained: “Earth Day came as a great shock to me because it had never occurred to me that the environment didn’t clean itself. I thought that water that flows along in a creek was purified by sunlight, and I guess I didn’t know a lot about where pollution came from. When I learned at the time of Earth Day how much pollution there was and how bad pesticides were, I instantly became very active in the pollution area of the environment.”

In the wake of Earth Day, Doris Cellarius drew upon her master’s degree in biology from Columbia University to become a leading grassroots activist and environmental organizer, especially against the use of pesticides and other toxic chemicals. Within the Sierra Club, she became head of several local and national committees that focused on empowering people in campaigns for hazardous waste clean-up and solid waste management. In her oral history interview from 2002, Doris Cellarius reflected on the impetus behind her decades of environmental activism: “I learned at Earth Day there was pollution. So, I think, having learned there was pollution, I decided that people should find out ways to stop creating that pollution.” Doris Cellarius wasn’t the only person whose life was changed by the events of Earth Day in Ann Arbor.

As a graduate student in forestry, a young Sierra Club member named Doug Scott co-organized the nation’s very first Earth Day teach-in at the University of Michigan. Their teach-in included the cast from the musical Hair, the governor of Michigan, several US Senators, as well as a public trial of the American car, which the students convicted of murder and sentenced to death by sledgehammer! I strongly encourage you to read the Sierra Club oral history of Doug Scott, who not only witnessed these events, but helped make them happen.

Fifty years ago, in 1970, the dynamic events surrounding the first Earth Day reflected how environmental issues could rapidly mobilize new publics for radical reform and institutional action. Indeed, the small organization created to nationally coordinate the first Earth Day took the name Environmental Action. Denis Hayes, the then-twenty-five-year-old national coordinator for Environmental Action, announced on Earth Day, “We are building a movement … a movement that values people more than technology, people more than political boundaries and political ideologies, people more than profit.” This exuberance for a new kind of environmental movement, according to historian John McNeill, arose “in a context of countercultural critique of any and all established orthodoxies.” But, at its root, Earth Day—and the flowering of concern for Spaceship Earth and all travelers on it—constituted “a complaint against economic orthodoxy.” According to John McNeil, “It was a critique of the faith of economists and engineers, and their programs to improve life on earth.” For new adherents to this ecological insight, the popularity of Earth Day’s events contributed collectively to “a general sense that things were out of whack and business as usual was responsible.” That all sounds terribly familiar today.

This year, on the golden anniversary of Earth Day, life all across the planet is out of whack and business as usual has come to a sudden stop. From climate change to the novel coronavirus to the deteriorating condition of American politics, a slew of increasingly complex and interconnected problems affect us all. But perhaps, this moment—like the one in 1970—offers a unique opportunity to think how we might begin things anew. Perhaps, as René Dubos advised on the first Earth Day in April 1970, we in 2020 can “take time to reevaluate what is needed for quality of life, to sift and sort alternatives … to look in a new way at what the future could be like, and then devise plans for making it so.” May it be so. May you help make it so.