Author: Amanda Tewes

Objectivity and Subjectivity in Oral History: Lessons from Japanese American Incarceration Stories

Sari Morikawa is an intern at the Oral History Center (OHC) of the Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley. She is a Mount Holyoke College history major with a keen interest in American history.

This fall, I had an opportunity to work on the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project (JAIN) with OHC interviewers Amanda Tewes, Shanna Farrell, and Roger Eardley-Pryor. For this project, I identified oral history interviews discussing Japanese American incarceration during World War II in the OHC’s collections. Later, I compiled and constructed an annotated bibliography for the team, as well as for future researchers. At the same time, I engaged with and acquired knowledge of basic oral history theories and methodologies. Through this project, I had a chance to reflect upon the idea of intersubjectivity and contemplate how this concept plays out in a real oral history project. This entire experience caused me to wonder how my own subjectivity—including my background as a Japanese woman and not an American citizen—might influence how I interpret and share these oral history narratives on Japanese American incarceration.

For the first phase of my internship, I engaged with prominent oral historians’ scholarly work and learned basic oral history methodologies and practices. In particular, the idea of intersubjectivity struck me. In oral history, intersubjectivity means that both the interviewer’s and narrator’s subjectivity, or identities and lived experiences, impact their interpretations of memories and shape the interview they co-create. In particular, Kathleen Blee’s article, “Lessons from Oral Histories of the Klan,” was very influential for me. In this article, Blee sheds light on the idea that historians need to grapple with how to tell people’s stories while considering their own social identities and perspectives, especially when they disagree. After briefly discussing the author’s main argument, Amanda asked me a question, “Do you think history can be objective?” This question struck me. At that point, I believed that objectivity in history was important to avoid romanticization of the past. For example, in order to justify the incarceration plan, the U.S. federal government conceptualized Manzanar as a “holiday on ice” and shared this interpretation with the general public. As a result, some of the oral history transcripts demonstrate (particularly white) narrators’ misunderstanding and misinterpretation of Japanese Americans incarceration. Thus, I believed that history should be neutral to prevent romanticization. Yet, my views on objectivity and intersubjectivity changed as I started writing the annotated bibliography and engaged more with oral history theory and methodology.

By the beginning of October, we started working on an extensive annotated bibliography. I identified oral history transcripts which discuss Japanese American imprisonment during World War II. It turned out Japanese Americans’ incarceration experiences were too diverse to generalize. It was wonderful to see that narrators who discussed the incarceration ranged from formerly incarcerated deaf family members to the War Relocation Authority officials to a fisherman who delivered fish to incarceration centers. I recognized how diverse their voices are and realized that the stories that we tell are not objective at all. Thus, history cannot be objective. For example, some formerly incarcerated Japanese Americans expressed their bitter feelings that life in incarceration camps was shocking and traumatizing. Some of them, like Nancy Ikeda Baldwin, even said that these experiences decreased their performance in school after their incarceration. On the other hand, others said that the incarceration camps were enviable experiences. One generation later, Eiko Yasutake confessed, “I was kind of a little jealous when you went to the camps, because that, for kids, was that side of it, that they were all together and kind of had that playtime if you will.” In fact, so many photographs from this time highlight Japanese Americans’ agency. Jack Iwata’s work uncovers Japanese Americans hosting beauty pageants, emphasizing Japanese Americans’ power to make the most out of their circumstances. This wide array of recollections, even among Japanese Americans, confused me. However, it made me contemplate how I would utilize the idea of intersubjectivity to share this nuanced and complex history with people who don’t really know about these incarceration experiences.

The question of how I would interpret these stories and share them with people who are unfamiliar with this topic led me to another question: how my identity as Japanese would impact interpretations of Japanese American incarceration. As a person who partially shares the same heritage and cultural background, I felt a sense of familiarity and interacted with interview transcripts with care. Encountering some of the Japanese words in oral history interview transcripts that don’t quite translate into English, such as ‘gaman‘ and ‘shikataganai,’ I felt a cultural connection to Japanese American prisoners. When someone discusses that formerly incarcerated Japanese Americans are hesitant to talk about their experiences, I recognize how Japanese culture made them react that way. My own subjectivity helped me grapple with these Japanese Americans’ incarceration stories. At the same time, I learned that I should also step back from my own subjectivity. Some of the Chinese and Filipino Americans’ transcripts on this topic allowed me to tackle this idea. Caroline and Frank Gwerder said, “[Filipinos] were fearful of what the Japanese might do.” These interviews reminded me of how Japanese imperialistic and super nationalistic policies and how they implanted fear on other Asian Americans and reshaped U.S. homeland politics. Since then, I felt more cautious about my national identity, in particular as a person coming from a country with this imperialistic past. That adage that “winners write history” nicely illustrates how imperialists write and rewrite history and leave behind the perspectives of marginalized communities. Recognizing this, I became to be more mindful about valuing the stories of incarcerated Japanese Americans.

Throughout this process, I realized that the inner dialogue between my identity, my interpretation of these oral history interviews, and how I would disseminate them to a larger audience is all subjective. Historians cannot avoid being subjective. In order to best reflect these interviews through my annotated bibliography, I would highlight their plight caused by the government’s racially discriminatory plan and Japan’s imperialistic military policy. Yet, more importantly, I would also emphasize incarcerated peoples’ agency and adoption of “gaman.” Utilizing my shared culture and history, as well as acknowledging the imperialistic past that my country made, I will utilize the oral history as bottom-up narratives to overturn the romanticized past.

Find out more about the oral histories mentioned here from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.

9/11 and Interviewing around Collective Trauma

“…I very rarely ask questions about 9/11 during oral history interviews, and I’ve been trying to grapple with why that is.”

As we approach the twentieth anniversary of 9/11, I’ve been reflecting on my own memories of that fateful day in September, and its impact on how I interview others about traumatic events. Indeed, I recently realized how deeply intertwined my thoughts about 9/11 are with my oral history practice.

The first time I spoke aloud about 9/11 – aside from discussing breaking news in the days that followed – was in my introductory oral history class with Dr. Natalie Fousekis at California State University, Fullerton in August 2009. This was nearly eight years after the original events, when the terrorist group al-Qaeda coordinated the hijacking of four passenger airplanes with the intent to crash them into major US targets. This led to a tragic loss of life and shook a sense of national security for many Americans.

As an exercise about collective memory, Natalie invited the class (from youngest to oldest) to share recollections of that day. Despite the age differences (approximately early twenties to early forties), as we went around the table, it was striking that roughly twenty different stories aligned so closely, as though we were all reciting the same narrative with slightly different words. With the exception of hearing the news while getting ready for high school, my own memories were much the same. This was, of course, in part due to the media coverage Americans saw of the Twin Towers falling over and over again, which helped create a collective memory of that day. But the similarity in omissions was striking, too. I don’t remember many people discussing the plane that hit the Pentagon or Flight 93, which crashed in the fields of Pennsylvania. Later dubbed Ground Zero, even in 2009, New York City dominated our memories of 9/11.

I also remember that though the mood in the classroom was somber, none of us cried or expressed an overwhelming sense of grief. Looking back, I wonder why there wasn’t more emotion around this discussion of such a traumatic moment. The eighth anniversary of 9/11 was only weeks away, and for those who had been teenagers in 2001, that day and the ensuing War on Terror had indelibly changed our lives. In part, maybe we were already trying to analyze our own experiences as oral historians rather than vulnerable individuals, interpreting what our collective memories meant rather than sitting with their personal heaviness. Or maybe this room of California students felt more removed from the horrors of that day due to physical distance from the sites on the East Coast. But it is also possible that even eight years later, we weren’t yet ready to address these memories as collective trauma.

In the more than a decade since this classroom discussion, I have conducted hundreds of oral history interviews – many of them discussing traumatic moments for individuals and the collective. Yet, I find it strange to reflect on the centrality of 9/11 to my early oral history training, as it has been a major pitfall in my own practice as an interviewer. About three years ago, while preparing an interview outline, I suddenly realized that my narrator’s work documenting and securing collections at a major arts institution coincided with this moment in history. Luckily the narrator agreed to share her memories, and we had a fruitful discussion about the ways in which, for a time, 9/11 impacted all levels of American culture. This experience helped me register that I very rarely ask questions about 9/11 during oral history interviews, and I’ve been trying to grapple with why that is.

One possibility is that I, like many others in the field, struggle with when an event gets to become “history,” and how we choose to memorialize it. To me, 9/11 feels like yesterday, not necessarily an historical moment upon which I need to ask narrators to reflect. And I am certainly guilty of collapsing historical timelines and not concentrating on the recent past, even during long life history interviews.

But I also suspect that my omission of 9/11 in interviews has a great deal to do with the traumatic nature of that day. Like many interviewers, I’ve sometimes been reluctant to introduce topics at particular points of an oral history for fear of creating a trauma narrative where there otherwise wasn’t. And until recent training, I was not even confident in my own skills tackling trauma-informed interviews. This hurdle has a clear solution: I need to prioritize discussing potentially traumatic topics like 9/11 in pre-interviews or introducing them in the co-created interview outline.

What is less clear is how to navigate my own trauma about 9/11. How do my own memories of that day impact my willingness to ask others about it? Am I too close to the subject to be able to speak with narrators about it? Quite possibly. But one complication for all interviewers is that unlike other traumatic events with a beginning and end date, 9/11 is an ongoing reality – even twenty years later. From the recent withdrawal of US troops from Afghanistan to the wide reach of the Department of Homeland Security to heightened airport screenings, we are all still living with the consequences of 9/11, and the trauma has not actually ended.

Twelve years after that classroom exercise around 9/11 and collective memory, I can appreciate Natalie’s methods all the more. I’ve learned over the course of my oral history practice that even deeply personal narratives can include elements of collective memory, and it is important to recognize such common threads in our lives as interviewers, as well.

I often preach that oral history practitioners need to acknowledge our biases so that we can better overcome them or even use them to our advantage. For me, examining my blind spot around 9/11 has also encouraged me to think about incorporating more recent and ongoing historical events into interviews. Not only is this reflection an important addition to the historical record, it is part of our essential work to help narrators make meaning of their lives through oral history. Similarly, evaluating my own blind spot around 9/11 has helped me recognize the blind spots in the collective memory of that day – such as narratives that leave out Flight 93 or the attack at the Pentagon – and encouraged me to think about how oral history can help fill these gaps. As we recognize the twentieth anniversary of 9/11, this work feels more necessary than ever.

JoAnn Fowler: Building the Foundations of SLATE

The Oral History Center has been conducting a series of interviews about SLATE, a student political party at UC Berkeley from 1958 to 1966 – which means SLATE pre-dates even the Free Speech Movement. The newest addition to this project is an oral history with JoAnn Fowler, who was a founding member of the organization in the late 1950s.

JoAnn Fowler is a retired Spanish language educator and was a founding member of the University of California, Berkeley student political organization SLATE in the late 1950s. Fowler grew up in Los Angeles, California. She attended UC Berkeley from 1955 to 1959, where she became active in SLATE and served in student government through Associated Students of the University of California (ASUC). After completing a master’s degree at Columbia University, she worked as a teacher, mostly in Davis, California. Find this interview and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.

I have previously written about the contributions of women members of SLATE and their sometimes complicated feelings about gender roles in this student political group. Fowler, however, did not feel that being a woman was not an obstacle for her in SLATE, and her interview includes memories of her own role in shaping the organization.

Fowler recalls being an outspoken SLATE member from the start. At her first meeting with the group in the fall of 1957, she recalled being overwhelmed by the advanced political theory many of the group discussed, and by one faction that she perceived “wanted to sit around and talk these things to death and not try to take any kind of action.” She felt that in order to be politically effective, the group had to take another approach:

I’m very verbal, I’m not shy at all, I speak right up, I don’t care, I have nothing to lose here. I say that, “You have to do something within the campus, you have to work within the campus. If you want to get all these things done, you have to get elected and do things on campus.”…So that’s the position I take, and that’s the position that Pat Hallinan takes, and so we win over the majority of these people…

Perhaps Fowler’s greatest contribution to the group was that in the spring of 1958 she ran for and won a position with ASUC on the SLATE ticket. This made Fowler and Mike Gucovsky the first SLATE members to have a voice in student government at UC Berkeley, and being able to affect progressive political change from positions of campus leadership was a key goal of the group. In speaking of her campaign platform, Fowler remembered:

If you were to name anything, we ran on all of it, but not all of that could be addressed during the campaign. Basically, it was: freedom of speech was addressed through [being] against the [House] Un-American Activities Committee and also by the relationship between professors and the students that should be confidential and the anti-Loyalty Oath. Then there was civil liberties in the South; in Berkeley with that housing ordinance that came up for vote; and on the campus that no fraternity or sorority should discriminate.

She continued discussion of that ASUC campaign, saying:

This was encouraged by Mike Miller. I didn’t mind running—that was going to be great—but I did mind speaking to big groups. I hadn’t had a lot of experience doing that, so he encouraged me to do that. I went around only two nights that I remember, and it was only to men—I never spoke to women—and only at the co-ops. That was my background; I’d come out of co-ops. I’d go in at dinnertime and I would speak for two minutes, maybe somebody introduced me and maybe somebody didn’t. I’d speak for two minutes to those very immediate concerns that I thought would be very appealing, and I would have this overwhelming applause. But I felt that anybody, any woman could have stood up there and gotten this overwhelming applause, because that’s the kind of applause I felt it was. I don’t know, maybe that’s just me. I don’t know who else spoke there. I don’t know if men spoke there, if other independents have reached out, I have no idea.

Even after she graduated from UC Berkeley in 1959, the lessons she learned from SLATE stayed with her. While living in Davis, she worked at a Hunt’s tomato factory, where she attempted to organize the office workers. Later, she headed the Davis Teachers Association, supporting a raise in teachers’ salaries. These organizing efforts didn’t always succeed, but Fowler saw them as part of a larger political project she’d been passionate about since her time in college. She explained, “But I did my bit, and so without SLATE, I wouldn’t have…tried, no, I wouldn’t have tried.”

Reflecting on how her involvement with SLATE impacted her life, Fowler observed:

I think it was one of the greatest experiences of my life. I never would have been as politically aware. I didn’t have that background, I didn’t take political science, I didn’t take sociology; I took economics, I took psychology. I never would have been as aware or as active as I was, I wouldn’t have had a group. When I lived in an apartment, I didn’t have a social group or I didn’t have—you were going to come on campus and leave campus because you certainly didn’t meet too many people coming out of that lecture hall of 500 people. I’m glad I have that experience, very much so. It was a good time in my life.

To learn more about JoAnn Fowler’s life and political work, check out her oral history! Find this interview and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.

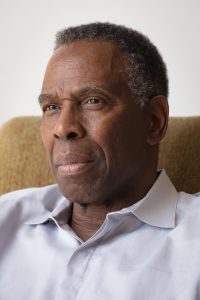

Charles Gaines: The Criticality and Aesthetics of the System

As a continuation of our work for the Getty Research Institute’s African American Art History Initiative, Dr. Bridget Cooks and I conducted a series of oral history interviews with the conceptual artist Charles Gaines. This interview was the first of several exploring the lives and work of Los Angeles-based artists, and celebrates Gaines’s extraordinary artistic contributions.

Charles Gaines is an artist specializing in conceptual art, as well as a professor of art at California Institute of the Arts. Gaines was born in South Carolina in 1944, but grew up in Newark, New Jersey. He attended Arts High School in Newark, graduated from Jersey City State College in 1966, and earned an MFA from the School of Art and Design at the Rochester Institute of Technology in 1967. Beginning in 1967, he taught at several colleges, including Mississippi Valley State College, Fresno State University, and California Institute of the Arts. Gaines has written several academic texts, including “Theater of Refusal: Black Art and Mainstream Criticism” in 1993 and “Reconsidering Metaphor/Metonymy: Art and the Suppression of Thought” in 2009. His influential artwork includes Manifesto Series, Numbers and Trees, and Sound Text; and he exhibited at the Venice Biennale in 2007 and 2015. Gaines is the recipient of several awards, including Guggenheim Fellowship in 2013 and REDCAT Award in 2018. Find this interview and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.

Hearing about Charles Gaines’s upbringing was especially helpful in framing his approaches to art. For example, he spoke about his mother’s influence on his life–particularly her musical inclinations. Though Gaines concentrated his early artistic studies on the visual arts, he also had a passion for music, eventually becoming a professional drummer. This connection to musicality and music theory features prominently in his conceptual works like Snake River and Manifestos. Indeed, in his Manifestos Series, Gaines turned the text of political manifestos into musical compositions based on a system he devised. He recalled, “Unconsciously, I began thinking about music as a kind of mathematics and this connection with text and language; I began to see the connection to language and systems.”

speakers, hanging speaker shelves. Photograph by Frederik Nilsen.

Further, Gaines shared about his exploration of conceptual work in the 1970s, and his consequential transition from an abstract painter to a conceptual artist:

Well as I said, those big abstraction paintings turned into these process-oriented works, and so that work demonstrated an interest in a systematic approach. It was a part of my research. I was looking for an alternate way of making work that was not based upon the creative imagination, was not based upon subjective expression.

This transition period also coincided with an eighteen-month sabbatical from teaching at Fresno State University from 1974 to 1975, when Gaines, his wife, and infant son moved to New York to explore his professional art practice. He recalled of the conceptual artists he met there:

But I did at that time, during that time in New York, become much more familiar with conceptualists, with what the conceptualists were doing. At that time, it provided a context for me. It was just before I started working with numbers but I was working with systems already, and so I felt that it’s true that, of anybody, my work, the language of my work fits best with those conceptualists.

Another major theme in Gaines’s interviews was his many years teaching art at colleges across the country, including the challenges of teaching at what he deemed conservative institutions. Despite these challenges, Gaines always looked for ways to mentor his students by not only helping them improve the quality of their work, but also by sharing his own insights into how to navigate the art world. He explained:

The thing I would always give my students advice about is that you can’t control career. That’s something that you shouldn’t even be thinking about. You should only think about the work, and you should also think about exhibiting the work, which I think is different from a career. You need to show people the work, so you make the work and try to get people to see it. In that process, something might happen, you can’t make it happen. In almost every story about how careers get kicked off, it’s because you happen to be at a right place at the right time, and somebody who matters notices something, and then things sort of roll into place…Ultimately, it’s the work that’s going to get you the exposure.

In addition to his own works and teaching career, Gaines has also made many important contributions to the art world through his theoretical writing and curation of exhibitions. In 1993, he co-curated Theater of Refusal: Black Art and Mainstream Criticism with Catherine Lord at the University of California, Irvine in 1993. This show, and Gaines’s catalog piece, explored racism in the art world by displaying Black artists’ work alongside reviews from (largely white) art critics, and questioned how and why they misread this work. Of this important exhibition, Gaines explained:

Well, I chose artists who were actively producing in the art world, and known to people. In a couple of cases, I showed a couple of people who were at an early part of their career, like Renée Green, for example, just started her career. But there were other people like Lorna Simpson and Fred Wilson, Adrian Piper, were completely well-known. The fact that they’re well-known artists was important to me because it allowed me to underscore this point that I was making: that is that there’s not much writing on the work of artists, even if they’re well known. The writing that there is [is] marginalized around the idea of race. The writers who wrote about [them] often thought they were writing positively about the work. They didn’t think that the way they approached the work was, in fact, marginalizing.

To learn more about Charles Gaines’s life and work, check out his oral history interview! Find this interview and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.

OHC Director’s Column for May 2021 features Guest Contributor Amanda Tewes

Looking to the Future of Oral History Work

by Amanda Tewes, May 2021 Guest Contributor

At this point, it is almost a cliche to point out that COVID-19 has indelibly reshaped our lives and work. But for many oral history operations, last year was for coping with the upheaval; this year is for rebuilding the practice. For us at the Oral History Center and for oral history practitioners around the world, this has also meant a fundamental change in how we conduct interviews—namely, going remote.

Even as we see bright spots in COVID-19 case reductions, oral history practitioners are starting to game out what interviewing best practices may be in the future, especially in regards to recording technologies. Many, like myself, are calling to embrace this moment, when so many individuals of all generations have become more familiar with remote interview platforms like Zoom; the potential seems great to record even more interviews that could not be completed before. Still others are champing at the bit to return to in-person interviews and yearn to leave remote ones behind.

However, oral history as a practice has always been adaptable, especially when it comes to technology. Early, heavy equipment like reel-to-reel machines gave way to cassette recorders, and later to light-weight digital cameras and recorders. And of course, today oral historians have embraced phone calls and Zoom as a way to continue interviewing narrators while social distancing—not to mention simply reaching narrators who live far away. And like today, adoption of these various technologies in oral histories has always mirrored cultural moments and the needs of the interview.

And yet, some still lament that the current technological expansion of oral history into remote interviews due to COVID-19 has forced us to lose important elements of rapport with our narrators, as well as the opportunity to physically and emotionally connect to particular places that have resonance in the interviews themselves. (For instance, I interviewed several individuals about their experiences with certain theme parks in the parks themselves, and the location of these interviews undoubtedly had an impact on their content.)

Indeed, there are tradeoffs to this new remote approach: do narrators have access to a computer and reliable Internet? How will Zoom fatigue impact interviews? And how does the inability to hug for joy or comfort influence rapport between interviewers and narrators? But I’m not so sure that in this switch to remote interviews we have lost more than we have gained.

Since shelter-in-place began for us in the San Francisco Bay Area in March of 2020, my interview schedule has been busier than ever—sometimes with multiple interviews on the same day. Thanks to Zoom, I have been able to interview narrators living across the country, all from the comfort of their own homes. And frankly, like other interviewers, I have still been able to build rapport with narrators by centering discussions of our mutual pandemic experiences. I have found that exaggerating my facial expressions during interviews translates well over the computer screen, and communicates to narrators not only that I am listening, but that I am still responding to the content of their words, despite our distance. In my experience, remote interviewing has not eliminated the emphasis on the human interaction between interviewer and narrator.

Moving forward, oral history practitioners may find themselves retaining at least a partial reliance on remote interviewing possibilities such as Zoom in order to allow for flexible schedules not reliant on cross-country interviewer travel, to keep project costs low that otherwise might have required extensive travel or expensive equipment, to ensure safety of narrators and interviewers in a world in which the spread of COVID variants remain uncertain, to maintain accessibility for individuals with mobility challenges, and the list goes on.

And while I do mourn the (hopefully momentary) loss of in-person interviews, I continue to see possibilities in remote oral history work. No matter the changing health landscapes, I believe remote interviewing will remain an important component of oral historians’ toolkits moving forward.

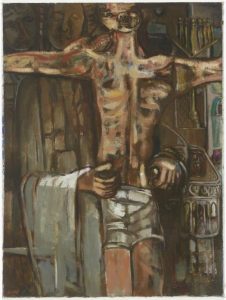

David C. Driskell: Life Among the Pines

In April 2019, Dr. Bridget Cooks and I had the privilege of conducting a series of oral history interviews with artist and educator David C. Driskell for the Getty Research Institute’s African American Art History Initiative. David and his wife, Thelma, welcomed us into their home, where we spent hours speaking with David about his singular life and extraordinary contributions to art and African American art history. It was a surreal experience to sit behind the camera and look around at beautiful works of art while David skillfully engaged us with stories from his life and work. In recounting his past, David employed accents and well-timed jokes that had us in stitches. It was a pleasure to watch a gifted storyteller at work.

One year later, I learned from Bridget that this kind, funny, and smart man had passed away from complications due to the coronavirus on April 1, 2020. In a year filled with so much loss and change, David’s passing still hit hard. With David’s passing, the world lost not only a bright personality, but also a brilliant mind who championed the field of African American art history. And despite the uncertainty of these early days of the pandemic, I am happy to say that the Oral History Center was able to expedite the finalization of David’s oral history transcript, which is now available to the public.

Now another April has arrived. At the Oral History Center our work remains remote, but people across the country have been vaccinated against the coronavirus, and there is hope that the end of the pandemic is in sight. It is past time to take stock and reflect on those we have lost and the stories that remain with us. For me, David Driskell’s interview is one such story with staying power.

David C. Driskell was an artist and professor of art. He was born in Georgia in 1931, but mainly grew up in North Carolina. Driskell graduated from Howard University with a degree in painting and art history in 1955, attended the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in 1953, and earned an MFA from Catholic University in 1962, as well as a study certificate in art history from Rijksbureau voor Kunsthistorische Documentatie in 1964. Beginning in 1955, he taught at several colleges, including Talladega College; Howard University; Fisk University; and the University of Maryland, College Park. His influential artwork includes Young Pines Growing, Behold Thy Son, Of Thee I Weep, and Ghetto Wall #2. Driskell has curated important shows highlighting African American art history, including Two Centuries of Black American Art and Hidden Heritage: Afro-American Art, 1800-1950. He also helped establish The David C. Driskell Center for the Study of Visual Arts and Culture of African Americans and the African Diaspora at the University of Maryland, College Park, in 2001. Find this interview and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.

Throughout his many years making art, David experimented with different media and subjects, often with the recurring theme of pine trees. Yet one of his most memorable pieces is Behold Thy Son from 1956, which is now at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. David painted this pietà – a subject in Christian art depicting the Virgin Mary cradling the dead body of Jesus – in response to the 1955 murder of Emmett Till. For many observers, this image captured the zeitgeist of the early Civil Rights movement.

Listen as David speaks about making this important piece:

When Bridget asked how David felt about Behold Thy Son over sixty years after painting it, he replied, “I think it is dated and tied to a time and period, but the fight goes on. It’s also showing you that time hasn’t changed that much. [Eric Garner and] ‘I can’t breathe.’ ” Indeed, the subject of violence against Black bodies remains tragically evergreen.

And yet, in part because of this turmoil for African Americans at midcentury, David found renewed artistic inspiration in the serenity of nature – especially pine trees. Listen as he explains this shift in his work:

David was indeed a talented artist and important educator, as Bridget eulogized so well in her obituary on ArtForum last year. But our oral history interviews with him also highlighted the fact that he was a deeply religious man, one who connected his spirituality and creativity with his passion for gardening. During an interview session after church on Palm Sunday, David said of these links between nature and religion, “From dust and dirt thou came, and so dust to dirt thou goest. I’ve got to be part of that process.”

He further explained:

“So gardening is to me like painting, in a way. It’s a part of the process of this creative spirit that I feel so close to. Can’t wait to get [to the house in Maine] and I often go to the garden before I go to the studio…Gardening is a part of my life. It’s a part of that kind of spiritual regeneration that comes with the natural process. It isn’t for me so much the biblical reference.”

As a further measure of the man, when we were wrapping up our final interview session, we asked David for his concluding thoughts, and he said, “Well, maybe the final say is none of this I could be doing without family.” He went on to praise his wife, Thelma, in particular for supporting his art career when it was just a dream.

To learn more about David C. Driskell’s extraordinary life and work, read his oral history transcript and watch his interview in full here, here, and here. Find this interview and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.

Kenneth Hamma: Antiquities and Technology at the Getty

Kenneth Hamma is a former employee of the J. Paul Getty Trust, where he held several positions, including associate curator of Antiquities and executive director of Digital Policy and Initiatives. He attended Stanford University and Princeton University, specializing in art and archaeology. Hamma taught at the University of Southern California, and became associate curator of Antiquities at the Getty Museum in 1987. He then held several positions in information technology at the Getty from 1997 to 2008 before consulting in the same field.

Hamma’s oral history is part of an ongoing series of interviews for the J. Paul Getty Oral History Project. As Hamma worked in many positions in various parts of the Getty Trust for over twenty years, he had a unique perspective about the growth of the institution and its various challenges.

Hamma began his professional career in academia, teaching archaeology and art history at the University of Southern California while also participating in a years-long dig of the ancient city of Marion in Cyprus. Yet, he made connections with the Getty Museum while teaching in the Los Angeles area, and pursued a position as associate curator in the Antiquities Department in 1987, where he worked for ten years. During this time, Hamma helped grow the Getty’s antiquities collection through acquisitions, and even managed a program that brought classical Greek theater like The Odyssey to life at the Getty Villa.

But eventually, Hamma felt it was time to move on and to pursue his interests in information technology. Listen to Hamma describe this professional transition at the Getty:

Hamma’s work in information technology led to him several positions at the Getty: head of Collections Information Planning at the J. Paul Getty Museum (1997-1999); assistant director for Collection Information at the J. Paul Getty Museum (1999-2004); senior advisor for Information Policy at the J. Paul Getty Trust (2002-2004); and executive director of Digital Policy and Initiatives at the J. Paul Getty Trust (2004-2008). In these positions, Hamma fought to create a more cohesive approach to technology and systems Trust-wide at the Getty, as well as for open access to information about its collections. Part of these challenges included changing the Getty’s approach to copyright management. Hamma sometimes faced pushback in allowing more open licensing for the Getty’s collection, but he explained,

“I was always of the opinion that the more open the Museum was, the better…what that meant to me changed over time, partly as I thought about it more but partly also as technology provided opportunities to be more open and more fluid with information. It seemed to me that it was the responsibility of the Museum to take advantage of those in every way that it possibly could.”

Hamma retired in 2008, and worked as an independent consultant for a decade, extending the ideas about information technology management he developed at the Getty to other arts institutions around the country. During his more than twenty years at the Getty, Hamma brought new ideas and changing technologies to the forefront of the Getty’s work, building the foundations for the institution’s current embrace of open content for arts education and research.

To learn more about Kenneth Hamma’s work at the Getty, check out his oral history!

Tradition and Innovation in the J. Paul Getty Trust Paintings Conservation Department

One of the pleasures of interviewing for an ongoing project such as the J. Paul Getty Trust Oral History Project is being able to draw connections between ideas and moments in time, and to the individuals who helped shape them. The Paintings Conservation Department at the Getty Trust is one such example. The development of this department mirrors the growth of the Getty from a small museum perched above the Malibu coast to its current iteration as a large organization with international reach. Over the last several years, I have been delighted to interview three people who not only saw this transformation and its impact on the Paintings Conservation Department, but helped build it up: Yvonne Szafran, Mark Leonard, and Joyce Hill Stoner.

Yvonne Szafran was the head of the Paintings Conservation Department from 2010 until her retirement in 2018. She joined the Getty Museum in 1976 through a work-study program in the Antiquities Conservation Department. In 1978, she became a conservator in the Paintings Conservation Department. (Yvonne Szafran: Forty Years of Paintings Conservation at the J. Paul Getty Museum)

Mark Leonard was the head of the Paintings Conservation Department from 1998 until his retirement in 2010. He worked as an assistant conservator of paintings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art before joining the Getty as an associate conservator of paintings in 1983. (Mark Leonard: Building New Traditions in Paintings Conservation at the Getty, 1983-2010)

Joyce Hill Stoner is a professor of material culture at the University of Delaware, Director of the University of Delaware Preservation Studies Doctoral Program, and painting conservator for the Winterthur/UD Program in Art Conservation. Dr. Stoner has a long history with the J. Paul Getty Trust, including as a visiting scholar to and traveling with the Paintings Conservation Department in the 1980s, working as the managing editor of Art and Archaeology Technical Abstracts, and serving on committees with the Getty Conservation Institute (GCI). (Joyce Hill Stoner: My Life in Art Conservation and Intersections with the Getty)

Through memories that span four decades, these interviews help illuminate the passion, skill, and vision that conservators at the Getty Trust have used to treat some of the world’s finest paintings, and to grow the Paintings Conservation Department into a world-renowned operation.

The years after Mr. Getty’s 1976 passing and the subsequent money his will provided his namesake museum proved to be a heady time to be at the Getty. Szafran recalled that the new capital offered unique opportunities for conservators that they might not have found elsewhere. She explained,

“They were the times at the Getty when the money finally came, acquisitions started rolling in, shall we say. It was such an exciting time to be at the Getty because new paintings were being acquired frequently. So as the youngest member of the Department, I was given great things to work on, just because we were so busy.”

Certainly money opened doors for the Paintings Conservation Department, but in thinking about what made it unique amongst its counterparts at other museums, Szafran, Leonard, and Stoner all spoke about its philosophical approach to conservation—one which differed from the “objective” way many taught art conservation in the mid-century United States. Listen as Leonard explains this subjective approach,

This approach to art conservation started to take shape in the mid-century United States, thanks in part to the influence of European practitioners like John Brealey at the Metropolitan Museum of Art—who also happened to be Leonard’s mentor. This style was also reinforced by Andrea Rothe, the former head of the Getty Paintings Conservation Department (1981-1998).

Another experience all three narrators shared was joining the Department for research trips that Rothe planned to Italy in the late 1980s. Stoner, who was already working at Winterthur, joined Rothe, Szafran, Leonard, and longtime Getty conservator Elisabeth Mention on one of these trips. Listen as Stoner recalls these trips that Rothe arranged:

Stoner and the others observed firsthand the differing conservation styles in Italy and engaged in conversation about what approach worked best for not only the Getty, but also for new students in the field. Stoner was actively teaching at Winterthur at the time, and discussed returning to the Getty for specialty training a few years later, videotaping the sessions in order to share them with her students. This willingness to invite non-staff conservators to such events indicates the importance of the Getty in fostering continuing education among its own staff and disseminating these ideas into the rest of the field.

These research trips to Italy also demonstrate that the Getty had an interest in cultivating talent, especially in the Paintings Conservation Department. This may be why a core group of four conservators—Rothe, Szafran, Leonard, and Mention—stayed together for around twenty years.

One thing that became apparent in the course of these interviews is that not all museums have in-house paintings conservation departments. And the fact that the Getty has supported this department from the beginning points to a dedication to succeeding in the field and to support the growing paintings collection in the Getty Museum.

During his tenure as head of the Department (1998-2010), Leonard continued to think about how to build public support for this work and expand international partnerships, especially in the wake of the fall of the Berlin Wall and the new access to museums and art collections to the West. His solution was to establish the Paintings Conservation Council. Listen as Leonard discusses his decision to create the Council,

Before joining the Getty Trust Oral History Project, my understanding of art conservation was limited. But in the course of interviewing Szafran, Leonard, and Stoner, I learned not only about treatment and techniques, but also about the important role the Paintings Conservation Department plays in the Getty Trust. Further, an in-depth look at this department underscores the transformation of the Getty into an international arts organization, as well as the people, talent, and innovation that pushed it forward.

To learn more about the Paintings Conservation Department at the Getty Museum, check out oral history interviews with Yvonne Szafran, Mark Leonard, and Joyce Hill Stoner!

Oral History and Political Organizing

By Eleanor Naiman

In 2020 Eleanor Naiman was a Biden-Harris campaign field organizer for the Nebraska Second Congressional District, working remotely to gain an electoral vote for Democrats. She is a recent graduate of Swarthmore College and completed an internship for the Bay Area Women in Politics Project with the Oral History Center in summer 2019.

Each of the 4,150 phone calls I made as a field organizer with the Biden-Harris campaign had a clear and stated purpose: to establish a voter’s support of Democratic candidates and to convince them to volunteer at a virtual phone bank. A detailed script drafted by the Biden HQ provided the framework for each conversation. Designed to maximize efficiency and recruitment shifts, the script encouraged organizers to get to a “hard ask” as quickly as possible: “We have phone banks at 4:30pm Central every day this week,” I’d explain. “Can I put you down for Monday and Wednesday?”

The direct nature of our recruitment script initially threw me off. My summer as an intern for the Oral History Center’s Bay Area Women in Politics Project taught me to take a subtler approach to questioning. I learned to ask open-ended questions that allowed narrators to tell their stories with authenticity and autonomy. I knew to prioritize the needs of my narrator over my own research objectives, working collaboratively to construct a life story that felt true to both history and memory.

In those early days of campaign work, I longed for the opportunity to sit down with each voter, as I had at the OHC, equipped with pages of notes of background research and confident in the strength of the relationship we’d built over pre-interviews and email correspondence. I missed the warmth and familiarity of in-person conversation; due to the nature of field organizing in a pandemic, the entirety of my conversations with voters took place over the phone or on Zoom. My conversations with voters seemed unpredictable and somewhat chaotic. Parents answered as they shuttled their kids to school, retirees picked up with the afternoon news blaring on a nearby TV, wives declined on behalf of husbands on the farm and in the field. I never knew where a conversation with a voter would take me. Would they hang up abruptly, perhaps after a quick jab at my candidates or an angry request that I take them off the list? Or would they linger on the phone, desperate for some form of human connection after months of pandemic-imposed isolation?

The conversations that fell somewhere between those two poles posed the greatest challenge. Somehow, in the five minutes allotted for each conversation, I needed to transform a weary voter into an eager volunteer. I found myself increasingly relying on oral history methodology to quell my anxiety about cold calls and hard asks. After all, I reminded myself, despite their obvious differences in form and purpose, an oral history interview and a voter outreach call posed the same basic problem: how to build trust through dialogue. I found myself listening as diligently as I had at the Oral History Center, noting and adopting the tone and lilt of a voter’s voice, sometimes even subconsciously, in an attempt to build rapport before my voter’s interest waned and I lost a potential volunteer. This meant performing in a matter of seconds the careful assessment of intersubjectivity I’d studied as an OHC intern. How did the voter perceive me? How did I see them? I knew that each conversation would require a balance of give and take, leaving both of us changed by its end. To a grandmother, alone in an assisted living facility, I became a granddaughter, or perhaps a memory of the political organizing and idealism of her youth. To a young voter, I became a friend and peer, commiserating about classwork and college stress. I reminded myself to that even on this small scale, the quality of my listening mattered just as much as the efficiency of my hard ask. Returning over and over to the tools and practices of oral history, I built relationships with voters whose dedication to change and hope for the future fueled my long nights and countless hours on Zoom. Together, we formed a community that ultimately flipped Nebraska’s second congressional district.

I came to appreciate the constant thrill of this sort of speed-interview. By November, I had learned to love catching a voter in motion, getting a peek into homes far from my own, and hearing anecdotes of daily struggle, loss, and hope that consistently reinforced the importance of this work. As I sat at my desk in my pandemic office, cut off from the world yet never closer to it, I felt an immense gratitude for the thousands of people who had let me into their lives. It was the same sense of awe and of appreciation that made me fall in love with oral history in the first place.

2020 Advanced Summer Institute Recap

In early August 2020, OHC staff gathered once more for a weeklong event: our annual Advanced Summer Institute, where we teach the methodology, theory, and practice of oral history to other practitioners. In 2020, however, COVID-19 upended our best intentions for an in-person event, and the OHC made the bold decision to turn this weeklong seminar – from lectures to small group discussions to interview exercises – into an all-digital experience. Certainly this was a sharp left turn for our office and required retooling. Nonetheless, we had a record number of applicants and 50 participants from around the world, which proves that the demand for oral history education remains strong even during a global pandemic. Despite changes for this year’s Advanced Summer Institute, I am now better able to appreciate what remains constant about the practice of oral history.

One way in which this all-digital format changed the Advanced Summer Institute was in increasing its international draw. In previous years, we have welcomed a smattering of participants from around the world. Admittedly, however, the additional cost for traveling internationally to Berkeley is something that has kept these numbers relatively low. In 2020, our all-digital format not only eliminated the cost of this travel, it also created a space for participants from several continents and timezones to join us for stimulating discussions – even in the wee hours of the morning – and share a variety of perspectives about interviewing across different cultures. Especially during a time when we are socially distancing from even our closest friends and neighbors, it was a joy to see people from around the world gather together in this way.

What did not change in our 2020 Advanced Summer Institute was the OHC’s emphasis on teaching oral history best practice through both practical experience and shared knowledge. Indeed, we doubled down on connecting participants to one another through an expanded interview exercise, wherein paired individuals planned a pre-interview and then engaged in 30-minute oral histories. They then switched roles so both could experience conducting an oral history and participating in one. From initial feedback, participants found this a valuable activity because it taught them how to ask better questions and to empathize with narrators. We also made sure to continue our small group discussions in the digital format so that participants could present their individual projects and ask for feedback in a smaller setting. This, too, proved important to sustain.

Despite these many successes, it is still important to acknowledge what we lost in this new digital format for the 2020 Advanced Summer Institute: the conversations in between sessions or during lunch that lead to meaningful connections, hands-on help with recording equipment, a distraction-free week of learning, and a sense of place near our offices at UC Berkeley. And yet, participating in this seminar – and indeed working as oral historians in the era of COVID-19 – seems to have encouraged all of us to examine the role of storytelling and documentation in this challenging moment. The resounding chorus I heard at the Advanced Summer Institute was that now more than ever we need oral history to help humanize the past and record the present. Personally, this experience reinforced my desire to connect with people – even over long distances – especially the narrators I interview in my own oral history practice.