Author: Amanda Tewes

Chinese-American Identity and Oral History Performance: Rewriting the Script

Miranda Jiang is an Undergraduate Research Apprentice at the Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley. She is a UC Berkeley history major graduating in Spring 2022.

In the fall of 2019, I joined an undergraduate research apprenticeship on oral history performance with Oral History Center interviewers Amanda Tewes and Roger Eardley-Pryor. Though I’d had some previous experiences with oral history, I wasn’t entirely sure what oral history performance was. I had my speculations: I was familiar with The Laramie Project and some other full-length plays which drew from oral histories. But no matter what the form of the performance would be, I understood that the project would take an approach to history that prioritized and shared the voices of ordinary people.

During the first few weeks of the semester, we discussed readings that fleshed out my understanding of oral history, then introduced me to multiple forms of oral history performance. Through readings such as Lynn Abrams’s Oral History Theory and Natalie Fousekis’s “Experiencing History: A Journey from Oral History to Performance,” I learned that the process of creating an oral history involves both the interviewer and the narrator (the person being interviewed). An oral history is a conversation. Both participants contribute to the content and direction of an oral history, and thus how an experience gets told. Oral history performance presents these experiences to the public, and places the experiences of multiple narrators in conversation with each other.

With these readings and assignments in mind, I searched through the Oral History Center’s vast archive of interviews to find sources for my own oral history performance. The only criteria I initially had in mind were that the subject I chose should be a story I knew little about, that I felt was undertold, and was centered in the Bay Area. I read interviews from the Freedom to Marry Project and the Suffragists Oral History Project, ultimately deciding on the Rosie the Riveter Project. It included interviews from people of African American, Chinese, Japanese, indigenous, and other backgrounds, and it was centered around the Bay Area.

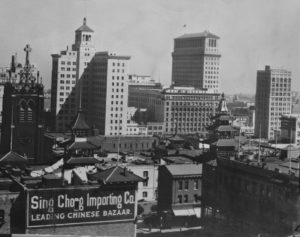

I eventually decided to focus this performance on Chinese-American experiences in the Bay Area. I hoped that by focusing on this one group, I could have more time to flesh out the details of their lives. I do not have my own living grandparents to speak to, so hearing these stories about what young Chinese-American people like me had experienced growing up in California in the 1920s to 1950s made me feel connected to people who lived nearly a century ago. Hearing them also made me realize just how varied our experiences were.

Over the next weeks, I compiled a large annotated bibliography of quotes from relevant interviews, highlighting themes which continuously reemerged. In the spring semester, Amanda, Roger, and I shared many conversations about what it means to create a cohesive script out of direct quotes from oral histories. When we chose which quotes to group together, which to place in conversation with each other, and how we ordered and extracted quotes, we were interpreting each quote’s meaning. We constantly thought about how to assemble a script that highlighted common themes in the experiences of Chinese Americans, without taking narrators’ words out of context or imposing our own interpretations onto the quotes and our audience.

I soon found that by placing quotes of similar subjects next to each other, meaningful similarities and contrasts revealed themselves on their own. For example, many of the interviewers asked if the narrators had experienced teasing as children. Alfred Soo, Dorothy Eng, and Theodore Lee all described growing up in neighborhoods where they were among the only Chinese people there. Soo, who grew up in Berkeley in the 1920s, did not recall any teasing from other children. Lee, who grew up in the 1930s in Stockton, described not being treated any differently, emphasizing the lack of “snobbery” among working-class white people. Eng, who grew up in Emeryville in the 1920s, described being persistently mistreated by kids and teachers throughout grammar school. As a Chinese American who encountered racial insensitivity in school in the early 2000s, I expected that stories of children who grew up in the “age of exclusion” (1882-1943) would easily reinforce my own experiences. And yet, these oral histories showed a more complicated reality than I anticipated.

Another primary goal of this performance is to point the general public towards reading the full transcripts of the interviews. In the final script, there is a quote from Royce Ong, who states that he “just [eats] regular American food.” When I first read this, I was amused and annoyed by how he discounted Chinese food as something strange, when it was his own culture. But reading more of the interview, I found that his comments revealed more about his unique creation of a Chinese-American identity. He discussed “Chinese American” and “Chinese” as very distinct identities, with different political interests. To Ong, he could be a proud Chinese American as someone who didn’t eat Chinese food and who also learned only English as a first language.

Working on this performance made clear that no universal set of criteria comes with identifying as Chinese American. It made me aware of the vast multitude of experiences of other Chinese Americans, which are different from my own and different from each other. The format of the script brought the diversity of Chinese and American life to the forefront, and allowed each narrator to speak about their experiences as they occurred. It was up to the audience to observe and consider the contradictions between quotes.

The final script I created acknowledges that different Chinese Americans had unique experiences, while also highlighting similar struggles and activities within the ethnic group. Many anecdotes are relatable to me, today, and to other Chinese Americans in 2020. And ultimately, while some narrators leaned more towards embracing American culture, and others more towards also preserving Chinese traditions, all of them expressed the same conflicts with identity as Chinese people living in California.

By mid-March, we had created a final draft of the script after many sessions of cutting, rearranging, and reading out loud. We initially planned to give the eight-minute performance at the April 29th Oral History Commencement in the Morrison Library, with four or five student performers of Chinese-American backgrounds. When the campus closed due to COVID-19, we switched to an online podcast format, with the same script and number of performers.

The podcast version will be available on The Berkeley Remix this summer. I’m excited to be able to share this performance with more people using the magic of the Internet. I hope you’ll stay tuned for more!

Podcast Listening for Social Distancing: Wind of Change

German heavy metal meets Cold War intrigue. If you are looking for a fun listen during shelter-in-place, I highly recommend the podcast Wind of Change!

German heavy metal meets Cold War intrigue. If you are looking for a fun listen during shelter-in-place, I highly recommend the podcast Wind of Change!

Following a rumor that the German band the Scorpions’ 1990 hit song “Wind of Change” was actually written by the CIA as Cold War propaganda, investigative reporter Patrick Radden Keefe turned this long-form piece into an eight-part podcast series documenting the song’s influence on politics and popular culture, as well as its potential connection to American clandestine operations. Throughout, Keefe toys with the tension as to whether or not this kind of CIA involvement in songwriting is likely. After listening, my takeaway is that it’s just wild enough to be true.

While many Americans have not even heard of the Scorpions, this German band that sings in English has diehard fans all over Europe and Asia. Formed in 1965 in Hanover, Germany, three of the five band members have been playing together since 1978. They continue to tour internationally.

And what makes the song “Wind of Change” so fascinating is its resonance with the zeitgeist of 1990. The song was supposedly written after the band played in Moscow in 1989 and was released shortly after the fall of the Berlin Wall. For many, the song represents the “change” happening across Europe that led to the collapse of the Soviet Union. But as Keefe points out, “Wind of Change” isn’t just the soundtrack to the end of the Cold War, but also a song with modern resonance. When he saw the Scorpions live in Kiev, Ukraine, alongside huge crowds, Keefe was reminded that the country was actually still at war with Russia, trying to maintain its post-Cold War independence. For Ukranians at least, “Wind of Change” is not just nostalgia, but a sort of call to arms.

Keefe’s previous work inlcudes his 2019 book Say Nothing: The True Story of Murder and Memory in Northern Ireland, which the Oral History Center chose as its inaugural book club pick. In Say Nothing, Keefe explores the challenges of The Troubles in Northern Ireland, alongside the murder of Jean McConville and the Boston College Belfast Project oral histories. In Wind of Change, Keefe encounters similar challenges working with former spies as he did with former revolutionaries in Ireland: lies and obfuscation.

The delight of listening to this story in a podcast format is the ability to hear the song itself, the enthusiasm from live Scorpions audiences, archival and new interviews, and provide some (but not enough for their taste) anonymity for former clandestine officers. But Wind of Change offers more than just great audio, it also takes the listener on a journey into how to investigate a thirty-year-old story, following oddball leads – even to a G.I. Joe convention – and invites skepticism about what information to actually believe. Indeed, the podcast also questions the nature of storytelling around this rumor and its role in continuing the myth making around the CIA. But Keefe also wonders: how do you uncover something that (if true) was among the top CIA secrets during the Cold War? As an oral historian, I would add that these events have also been diluted by memory and time, and those who can speak to the true origins of “Wind of Change” may no longer be able to do so.

Part cultural history and part investigation into Cold War operation, Wind of Change also documents the CIA’s other attempts at cultural influence. From Louis Armstrong to Nina Simone to Doctor Zhivago, Keefe reiterates the CIA’s long history of using popular culture to convey the principles of Western democracy and undermine communism. Further, Keefe points to the very nature of rock and roll as ripe for use as propaganda: the genre was effectively banned in the USSR, so the act of listening to the music itself was a proxy for political rebellion.

The podcast Wind of Change is not just a fun listen about a campy band and Cold War CIA operations, but also a compelling story and a great distraction. Find out more about Wind of Change, or listen to all eight episodes right now on Spotify.

Storytelling at a Distance: Staying Connected while we are Apart

…we can remain physically distant without social isolation.

There is no doubt we are living through unprecedented times. The threat of COVID-19 and the necessity of social distancing has changed how we work, educate our children, and move through the world. And yet, if there is a silver lining in this public health crisis, it is the opportunity to reconnect and recalibrate our relationships with those we love.

For many of us, social distancing has also meant literal separation from those we love. This can create a profound sense of loneliness for all of us, especially older generations. But remember: in this era of user-friendly technology, we can remain physically distant without social isolation. To combat this sense of loneliness, perhaps you are already ramping up the phone calls and video chats to grandparents and others.

California Governor Gavin Newsom has challenged all of us to “meet the moment.” For us at The Oral History Center, that means sharing our expertise as listeners and communicators with you. With our backgrounds in oral history life interviews, we want to offer tips and question prompts so you can have more engaging and meaningful conversations with the important people in your life – even at a distance.

What we’ve learned through our experience as interviewers is that sometimes the simple act of listening can bring a great deal of comfort. Even if your questions illicit the same stories with familiar cadences, we’ve seen how just sharing the story can bring joy to the teller. And there is a possibility that you will learn something new each time! Listen for new words or framing in every telling.

But how to get the conversation started? Here are some major storytelling themes we use to frame oral history life interviews, as well as some example questions to get you started:

- Childhood

- Home and Place

- Examples:

- What was it like growing up in ______ in the 19___s?

- What did your neighborhood look like?

- Examples:

- Childhood Passions

- Examples:

- You trained hard to be a ballet dancer. Can you tell me what that was like?

- Examples:

- Holidays and Traditions

- Examples:

- What did Thanksgiving dinner look like at your house?

- Examples:

- Home and Place

- Education

- Elementary and Secondary

- Vocational or College

- Examples:

- You graduated from college in 19____. What did you do next?

- Examples:

- Etc.

- Career

- Examples:

- What made you choose to become a _____?

- How do you think your background as a ______ impacted your work as a _____?

- Examples:

- Personal Relationships

- Familial

- Examples:

- What do you remember about your grandparents?

- What kind of values did you acquire from your parents?

- Examples:

- Romantic

- Examples:

- How did you meet Grandpa? What did you like about him?

- Where did you go on dates?

- Tell me about your wedding.

- Examples:

- Etc.

- Familial

- Historic Events

- Examples:

- What do you remember about the moonwalk?

- I know you were at Woodstock in 1969. What was that like?

- Examples:

Pro tip: If you hear a new or particularly interesting story, follow up with more questions! For example: I’m not familiar with that term/event. Could you tell me more about what that is?

Pro tip: Be an active listener! Even over the phone or a video call, listen to what your family member is saying and engage with it. You may even listen for what they are not saying. Is there something you think they don’t want to talk about, or a gap in the story you can help fill with another question?

Pro tip: Try parroting their words! For example: You said you had the time of your life. Why was that?

Pro tip: Try to ask open-ended questions! You don’t want to ask a question where the only possible answer is “yes” or “no.” That doesn’t make for very stimulating conversation. Try questions like: Can you tell me about x? Tell me more about y. Can you describe z?

Pro tip: Some of the most rewarding answers follow reflective questions that ask the storyteller to make meaning of their past, sometimes in conjunction with their present. These questions usually come at the end of a discussion around a particular topic or story. For example: What did that mean to you? Or: Wow, you’ve worked so many different places! What connections do you see between these jobs?

We at The Oral History Center value the time and conversations we share with folks in our professional work, and treasure these moments in our personal lives. With these tips and question prompts, we hope you can keep connection and conversation alive in your own lives. After all, storytelling is a great antidote to isolation.

Podcast Listening for Social Distancing: Past Present

Looking for new podcast recommendations as you shelter in place? If you are like me, you are burning through your regular playlist at an alarming speed. To cut through the boredom, I’m sharing one of my favorite podcasts: Past Present.

Past Present is a weekly podcast hosted by a panel of historians who give historical context for a variety of contemporary topics. Fittingly, the show’s motto is “Hindsight is foresight.” Historians Nicole Hemmer, Natalia Mehlman Petrzela, and Neil J. Young cover topics that range from Greta Thunberg and youth climate activism to the appeal of Marie Kondo to the political power of women’s rage. Hosts bring their own academic specialties and personal interests to the discussions, which means I always walk away with different perspectives and new information.

As Past Present pulls inspiration from popular culture and the news of the day, lately the show has been covering topics such as face masks, quarantines, and just this week cabin fever. This is my third week working from home, and I’ve certainly been feeling restless in a way that even daily walks don’t solve. Past Present host Nicole Hemmer validated that indescribable feeling when she said that cabin fever may not be a disease, but it is “a measurable set of symptoms” with “restlessness, sleepiness, and irritation.” Check, check, and check.

The hosts also share that the term “cabin fever” may have started in the early twentieth century, but it was a recognizable concept in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Think ship-bound sailors or people stuck in unelectrified cabins during snowstorms. But Neil Young points out that “as isolated as we are,” the twenty-first century allows for digital connectivity that is unique from all previous eras in “human history.”

Now, I recognize that it is pretty meta that as I shelter in place at home and start to get a little stir crazy, I look to a discussion on the history of cabin fever as a cure. But I find this oddly comforting. Not only is cabin fever not a new phenomenon born in the time of COVID-19, compared to my ancestors, I am sitting pretty with Internet access and the ability to contact the outside world – even though I may not yet know when this physical isolation will end.

And then, of course, there is my favorite Past Present segment, “What’s Making History,” when hosts point to current events and popular culture as historical trends to keep an eye on. This week, come for the cabin fever conversation, stay for Neil Young’s discussion of what’s behind the new teenage trend of “Virginity Rocks” t-shirts. I had no idea, either.

I hope you love Past Present as much as I do. Treat yourself to a few minutes of listening that’s informative, entertaining, and distracting. Enjoy!

What are YOU listening to? Share with us on Twitter: @BerkeleyOHC

Howardena Pindell: Artist, Teacher, and Social Observer

Howardena Pindell is a painter and mixed media artist, as well as a professor at State University of New York at Stony Brook. She earned a BFA from Boston University in 1965 and an MFA from Yale University in 1967. Pindell worked at the Museum of Modern Art from 1967 to 1979, where she held several positions, including exhibit assistant, curatorial assistant, and associate curator. She cofounded the A.I.R. Gallery in 1972. Pindell has taught in the Department of Art at State University of New York at Stony Brook since 1979.

Pindell’s interview is the first in a series of oral histories with prominent African American artists for the Getty Research Institute’s (GRI) African American Art History Initiative. These oral histories complement the GRI’s ongoing work to collect, preserve, and interpret the art and legacies of these artists.

Pindell was born in 1943 and grew up in segregated Philadelphia. Thanks to the support of her parents and her demonstrable talent, Pindell had a great deal of exposure to art early in life. She went on to study at Boston University and Yale University, then moved to New York in the 1960s. In New York Pindell began working at the Museum of Modern Art while also continuing to paint. She recalled, “…I was working five days a week, and I was used to having natural light, and I didn’t have natural light.” As natural light is so important to a painter, and her work schedule cut into daylight hours, Pindell started experimenting with mixed media in these years – a practice she has continued to expand.

Perhaps Pindell’s best-known work is Free, White and 21, a video performance piece from 1980 that is a commentary on her experiences with racism and sexism. Listen to Pindell recount the logistics of creating the piece.

Free, White and 21 also relates to many of Pindell’s ongoing challenges with racism in the women’s movement and the art world at large. Though she was a cofounder of A.I.R. Gallery in 1972 – the first artist-run gallery for women in the United States – as an African American woman, she often felt marginalized in discussions about how to expand opportunities for women artists.

Pindell also spoke at length about her work as a professor of art, and her approach to teaching. Having been academically trained, she worked with many different professors and knew what teaching styles she would and would not emulate. Further, she saw working with students as important to her practice as a working artist. Pindell explained, “I think teaching helps me a lot, just so it keeps me fresh, because I can help the younger students – and in some cases, older students – with their work with formal issues. That keeps me informed about how I should think about my work, as well.”

Pindell’s story highlights the challenges of being a working artist, the importance of teaching others, fighting racism and sexism in the art world and beyond, as well as the long-overdue recognition of African American artists.

To learn more about Howardena Pindell’s life and work, check out her oral history!

“They Got Woken Up”: SLATE and Women’s Activism at UC Berkeley

For students across the country, college is a time of political awakening. And perhaps no other university has earned its reputation for radical student politics quite like UC Berkeley. Indeed, mid-century political activism around civil rights, the Vietnam War, and the Free Speech Movement has shaped how students, faculty, and administrators experience life at Berkeley today.

However, one important part of Berkeley’s political history that often gets left out of the conversation is the New Left student political party SLATE. SLATE — so named because the group backed a slate of candidates who ran on a common platform for ASUC (Associated Students of the University of California) elections — operated between 1958 and 1966, and ignited a passion for politics in the face of looming McCarthyism and what many perceived as the University of California’s encroachment on student rights to free speech. These students translated political theory they learned in the classroom to action, even when it went against University policies. Perhaps SLATE’s most important ideological contribution to Berkeley’s campus and to other social movements is the “lowest significant common denominator.” This concept allowed the group to form a big tent coalition between Marxists, liberal Democrats, and others by only choosing political positions and actions that the whole group could agree on. As a result, the group became involved with civil rights, labor organizing, and anti-war protests on campus and across California. Most notably, in May of 1960, SLATE and other student activists protested the HUAC (House Un-American Activities Committee) hearings at the San Francisco City Hall. In response to the peaceful sit-in, police blasted students with fire hoses and dragged them down stairs before placing them under arrest. This event was emblematic of SLATE’s commitment to activism, even when it came at personal risk.

In recent years, the Oral History Center of the Bancroft Library has conducted a series of interviews with members of SLATE to keep alive memories of the group’s influence on ideology and political infrastructure at UC Berkeley.

An essential part of SLATE’s story is the contributions of its women members. SLATE operated at a time before the women’s movement, but its work became an important introduction to political organizing for a generation of women students at Berkeley. These women were dedicated members of the group, but often felt sidelined in SLATE leadership. And yet, their work helped to change political culture and campus life at Berkeley. Three of these groundbreaking Berkeley women are Cindy Lembcke Kamler, Susan Griffin, and Julianne Morris.

Cindy Lembcke Kamler was just a freshman when she connected with SLATE in the spring of 1958, drawn in by the political ideals of the group dominated by male upperclassmen and graduate students. Susan Griffin and Julianne Morris were among the second generation of SLATE activists and joined the group around the same time in 1960 — after the famous HUAC protest.

All of these women came from politically left families who feared encroaching McCarthyism. Griffin and Morris also had connections to Judaism. These backgrounds helped ignite a political consciousness in these women that led them to SLATE.

Certainly Kamler, Griffin, and Morris’s oral histories contribute to the larger archive of SLATE history, but they also speak specifically to their experiences as women in this group. For instance, Griffin and Morris recalled instances of feeling marginalized and of being left to do what Morris called the “scut work,” like mimeographing fliers and cooking for hungry activists. This work, while essential to maintaining operations, felt to them like gendered tasks. For her part, Kamler doesn’t remember gender discrimination in SLATE. She insisted, “Oh, no, I never made coffee or any of that stuff.” And yet, Griffin recalled that several years later at a meeting of SLATE women in the 1970s,

“We were recounting how there was this prejudice against us and we were never allowed to have leadership positions. And husbands and boyfriends and guys from SLATE showed up at this meeting and started making fun of us and broke the meeting up. They thought that was the end of the story. Little did they know, [laughs] that was just the beginning of the story.”

These tensions came to a head at a 1984 SLATE reunion in which women newly empowered by feminism expressed displeasure with the way they had been treated while working for the campus political group. Many of the men denied there had been discrimination, but others took it to heart and sincerely apologized. Morris explained, “There were a lot of women who were really angry about how it had been. I don’t know that I was angry, in the sense that I really felt it was a different time and one can’t judge one time by another. But there was no question that that’s the way it was, and that’s what kind of was accepted.” Watching these events unfold, Kamler recalled, “I was just sitting there stunned. I didn’t do any of that stuff. I ran for office, I got elected, I was chairperson.”

Indeed, while there may have been invisible barriers for many of the women involved in SLATE, there were still opportunities to grow as individuals and leaders. Kamler ran for second vice president in the spring of 1958 and lost, but ran again for representative-at-large in spring of 1959 and won. She also served as the chair of SLATE for some time, helping to shape the group’s platform and activist agenda. Even Griffin and Morris were encouraged to run for ASUC office in the early 1960s, and had to learn how to campaign and feel confident in public speaking. Morris especially found running for office to be a formative experience. She remembered,

“And that was, for me, a big experience, because as I said, I was shy in terms of speaking out and I didn’t think that I could do it. And Mike Miller kept urging me to do it and saying, ‘You can do this. I’ll help you if you want, but you can do this! You’re going to be able to go to all of these fraternities and talk to them about ROTC. I just know you can do it.’ So I did it, and I really was very frightened about doing it, and I actually did fine. So that was, for me, kind of a breakthrough, that I was able to do something like that, because it wasn’t easy for me at the time.”

But as their lives became less centered around the UC Berkeley campus, these women drifted away from SLATE. Kamler married and left the group after the spring of 1960. Griffin and Morris had decreased their participation in SLATE or left campus entirely by 1964. And yet, as their oral histories reveal, the experiences these women had as Berkeley undergraduates in this student political party shaped their perspectives about politics and activism for years to come. For both Griffin and Morris, this activism took shape as involvement in the women’s movement. Griffin explained, “The guys may not have known it, but they were training feminist activists in all that period.”

Thinking about the longer arc of SLATE’s impact on the lives of its dedicated members, Morris recalled of a reunion in the 1990s:

“One of the things that we did was that we went around as a group and talked about what our lives were like now. And no one in that whole group went into business. Everybody was an organizer, a teacher, a social worker, a psychologist. It was so interesting that this group of people kind of, in some ways, stayed true to what we all went through in college. It really formed our lives.”

But most importantly, what these women learned from their time with SLATE was the importance of building and sustaining community in activist groups. For Morris, joining SLATE helped her find a place where she belonged. Griffin pointed to organizations of politically like-minded individuals as ways to create belonging and “joy” through an almost spiritual experience of protest.

And yet, the political work of Cindy Lembcke Kamler, Susan Griffin, and Julianne Morris wasn’t just personally fulfilling. For these individuals and generations of other women students, their political activism at UC Berkeley left an indelible mark on the campus. In thinking of this legacy, Morris reflected, “…it was one of the first…of the Left student movements. And I think it influenced a lot of people in that regard…I’m not at all sure that the Free Speech Movement would have happened without SLATE.” She concluded, “I think we were very successful in those years. We got a lot of people elected to the campus political organization, and I think people started thinking, at Cal, a little differently. They got woken up in a way that perhaps they would not have been.”

To learn more about these activist women at Berkeley and the history of this early student political party, check out the Oral History Center’s SLATE Oral History Project.

Kathleen Dardes and the Global Impact of the Getty Conservation Institute

The Getty Oral History Project includes interviews with individuals across the spectrum of the Getty Trust, including the Getty Conservation Institute (GCI), which does international work to advance the field of art conservation. Of the four programs in the Getty Trust, the GCI stands out both for its scientific collaboration with other Getty entities, and its dedication to sharing conservation information worldwide. Kathleen Dardes’ lengthy career working in various GCI training programs is emblematic of this mission.

Kathleen Dardes is the head of Collections at the Getty Conservation Institute. She studied art history and classics at Temple University in the 1970s, and then went on to study art conservation at the Courtauld Institute of Art in the 1980s, specializing in textile conservation. Dardes then worked as a conservator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine, and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. She joined the GCI in 1988 as the senior coordinator for the Training Program.

When Dardes joined the GCI in 1988, this Getty program was only three years old and trying to establish itself in the field. Dardes recalls working to build credibility as an international art conservation organization, and struggling against “skepticism” about this new Getty entity:

“I think part of it had to do with the fact that we were so darn rich, and we could buy pretty much anything we wanted and could do anything we wanted, and we weren’t beholden to anyone except our trustees. That gave us a certain freedom, which I think was sometimes resented in the broader field. So we had to prove ourselves.”

Part of the way the GCI proved itself was investing heavily in the international training programs Dardes helped create to share conservation best practices worldwide. These included the idea of preventive conservation, or delaying the deterioration of objects through procedures like managing collections environments. Dardes explained the need for this training, saying,

“In the field, you’d hear these funny stories about people making all sorts of elaborate measures to control environments in a gallery space or storage area, but the roof was leaking [laughs] or there was a pest issue or something. So we were looking at the small details, and not the larger system that the museum is.”

In recent years, the GCI has undertaken a project called MEPPI or Middle East Photograph Preservation Initiative. Dardes explained that the GCI and several partners worked hard to establish much-needed photograph preservation courses throughout the Middle East to help institutions protect these collections. This project included many challenges, not the least of which is political instability. In her interview Dardes shared the inspirational story of one MEPPI participant’s dedication to conservation, even in the midst of the Syrian Civil War:

“When we arranged a follow-up course in Lebanon, which was open to people from throughout the region, one of the participants in Syria, at great personal risk, got on a bus with her father, who was there to protect her, and took a bus from Syria to Beirut. Took her two days to do that, a trip that normally takes half a day. Couldn’t fly because it was too difficult to go to the airport, too risky, but came to Beirut to be with her old colleagues and take a course—which we all found absolutely stunning. But that’s how committed she was, not only to the course itself, to the collections she was in charge of, but also to the network that was forming. She wanted to see her old colleagues and be involved in this thing called MEPPI. So it sounds very pollyannaish, but it was a wonderful thing. People who don’t often have the opportunity to be involved in projects like this don’t take them for granted. It was something that we all thought was remarkable.”

Though she has not explicitly used her skills as a textile conservator while at the GCI, Dardes has found opportunities to engage with the larger implications of cultural heritage around the world. Indeed, being a part of the Getty Trust has opened global opportunities for her—and the GCI—to share and teach conservation best practices on an incredible scale.

To learn more about her work with the Getty Conservation Institute, check out Kathleen Dardes’ oral history!

From the Archives: Irvin Shiosee

By Miranda Jiang

Miranda Jiang is an Undergraduate Research Apprentice at the Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley. She is a UC Berkeley history major graduating in Spring 2022.

“I just can’t go out there with my Indian costume, because when I do that they might think, you know, oh, here comes a savage Indian.” — Irvin Shiosee

In 1942, Irvin Shiosee, a member of the Laguna Pueblo of the Southwest, moved with his family to Richmond’s boxcar village. Along with many members of the Acoma Pueblo, members of the Laguna Pueblo moved to this village (often referred to both as the Santa Fe Indian Village and the Richmond Indian Village) beginning in the 1920s. This migration followed a verbal agreement with the Santa Fe Railroad in California, which promised them employment in railroad maintenance and construction.

As part of the “Rosie the Riveter” project, the Oral History Center has conducted over 250 interviews with individuals who lived in the Bay Area during World War II, including people who lived in Richmond’s boxcar village. In his 2005 interview, Shiosee recalls his childhood there: he describes rows of around sixty boxcars placed along the railway, each housing one or more families. The children’s playground was a small “swamp” where they would take makeshift rafts and search for tadpoles. Among other anecdotes, Shiosee describes how his father built his family an oven to make sure they didn’t “lose any of [their] traditional food,” such as sweet “Indian pudding” made in the oven overnight.

Shiosee’s life within the village often seemed like a separate world from life outside and public school. Whereas day school at his old reservation was with other members of his tribe, at Peres Elementary School, there were Richmond-area children of many ethnicities. He had to learn English through Dick and Jane, and indigenous students were only allowed to speak English. He describes how students would “squeal on [them]” if they heard Shiosee or other Pueblo kids speaking Keresan. Subsequent punishments included standing against the wall or completing chores such as wood-chopping and cleaning the bathroom.

Shiosee also encountered stereotypical perceptions of indigenous people through his interactions with other children. On the first day of school, the teacher couldn’t pronounce his last name while introducing him to the class. He could see the surprise on his classmates’ faces upon hearing that he was an “American Indian boy.” The media only represented people like him in stories of “cowboys versus Indians,” so to these American children, indigenous people were the enemy.

“So that’s how they saw me,” he says, “as a savage Indian, I guess.”

Neither did the administration show much support. Children viewed him as a figure from fables and histories, and they would come up to pat him. When he whacked their hands away, teachers would send Shiosee to the principal’s office where he would be disciplined for fighting.

As Shiosee grew older, he became more and more aware of two separate realms. In his life outside the village, he knew he would face hostility if he showed his Pueblo identity. He describes walking to junior high school in the morning:

“I had to take off my Indian costume and hang it on this fence that I had to go through, and then put on my street clothes… ”

Yet despite going to school in an English-speaking environment and being pressured to assimilate, Shiosee remained closely connected with his culture and language. At the end of the interview, Shiosee describes his relationship with English and Keresan:

“English language to me is like I’m copying somebody. It’s not my natural language. The language that I speak comes from my heart on to you, you know. But to imitate somebody is not really from the heart. It’s coming from the mouth.”

In 1982, the Santa Fe Railroad shut off the power to the village. Although Richmond’s boxcar village was populated for around 60 years, it is now a relatively little known piece of Bay Area history. It has been documented in a number of writings, including essays by emeritus Oregon State University professor Kurt Peters (see “Boxcar Babies: The Santa Fe Railroad Village at Richmond, California, 1940-1945”). An event at Richmond’s Native Wellness Center in 2009 included three former inhabitants of the village as speakers, two of whom have interviews with the Oral History Center.

The boxcar village no longer exists physically, nor does it seem present in the Bay Area’s public consciousness. Although the inhabitants of the village attended local schools and events, and were spatially near other Bay Area neighborhoods, the Pueblo people preserved their culture and ways of life within the Richmond boxcar village. Ensuring knowledge of the Pueblo’s long history in the Bay Area is an important step towards recognizing what Shiosee already states in his interview: that rather than being faraway relics of history, he and his people are part of the present.

As a first step to learning more about the lives of Laguna and Acoma Pueblo people at this remarkable settlement, I encourage you to view the Rosie project’s compilation of interview segments related to the village. I further recommend reading and watching the full interviews, such as Irvin Shiosee’s interview.

2019 Oral History Association Conference Review

This year’s annual meeting of the Oral History Association (OHA) was hosted in Salt Lake City, Utah, where we caught just a glimpse of the region’s famed winter season, but were kept warm by invigorating discussion of oral history best practices and challenges.

This year’s annual meeting of the Oral History Association (OHA) was hosted in Salt Lake City, Utah, where we caught just a glimpse of the region’s famed winter season, but were kept warm by invigorating discussion of oral history best practices and challenges.

At the OHA conference I was especially impressed by the number of panels on doing oral history with indigenous people. In the roundtable session “Native American Stories of Peoplehood,” panelists grappled with how they incorporated oral tradition from their indigenous communities into oral history. It left me with a good reminder: narrators’ histories do not necessarily begin at birth, and their ancestors may play a large role in how they frame their own lives. One audience question from this session also asked when and how to include proprietary information about tribes in oral histories (i.e.: sacred stories, songs, ceremonies). One panelist remarked that this complicated area is something to review with both narrators and tribal elders. And yet, even when not interviewing in indigenous communities, it is important to discuss parameters for interviews long before pressing record!

Another highlight was the keynote speaker Isabel Wilkerson. The session was standing room only as Wilkerson spoke about her 2010 book, The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration. Wilkerson walked the audience through her process of finding and interviewing individuals whose life experiences humanized the stories of the twentieth-century Great Migration of African Americans from the South to the North, Midwest, and West. I groaned in sympathy as she recalled difficulties in finding narrators. But most importantly, I was drawn to Wilkerson’s understanding that oral histories are precious and time-sensitive products that often need to be prioritized over extensive archival research. I, too, have lost narrators before being able to interview them, and I have often wondered what stories they could have told to change the historical record as we know it. In short, Wilkerson validated the work of oral history, and reminded us that the most important work oral historians do is to help others tell their stories, especially when they change how we view the past.

After attending sessions on making oral history a sustainable career, I walked away from this year’s meeting with an even greater sense of the importance of building a community of oral historians beyond the academy and formalized training programs. Often it is the practitioners on the ground who best connect to under acknowledged individuals with important stories to share. So, as an interviewer with a seat of privilege, my questions to other practitioners are: how do we support oral historians working in the field? How do we further democratize oral history? I look forward to continuing these discussions next year in Baltimore!

Women of SLATE: Susan Griffin and Julianne Morris

The Oral History Center has been conducting a series of interviews about SLATE, a student political party at UC Berkeley from 1958 to 1966 – which means SLATE pre-dates even the Free Speech Movement. The newest additions to this project include two women who joined SLATE in the early 1960s at a tumultuous time at UC Berkeley: Susan Griffin and Julianne Morris.

Susan Griffin is an accomplished writer, and was a member of the UC Berkeley student political organization SLATE in the early 1960s. Griffin grew up in Los Angeles, California. She attended UC Berkeley, where she became active in SLATE, attending protests and engaging in political discussions. Griffin left Berkeley in 1963, but continued to work as a writer in the San Francisco Bay Area, producing many works, including Woman and Nature: The Roaring Inside Her. Over the years, Griffin remained active in causes of social justice, including the women’s movement and anti war protests.

Julianne Morris is a former social worker and mediator, and was a member of the UC Berkeley student political organization SLATE in the early 1960s. Morris grew up in Compton, California, and attended UC Los Angeles, where she helped found the student political group PLATFORM based on discussions with SLATE members. She then transferred to UC Berkeley, where she became active in SLATE, attending protests and running for ASUC student representative. Morris stayed at UC Berkeley to earn her master’s in social work. She then moved to New York City in 1964 and was a social worker for many years, where she helped start women’s centers, rape crisis programs, and became a part of the women’s movement. She returned to Berkeley in the early nineties and reconnected with former SLATE friends through reunions and an ongoing political discussion group.

Griffin and Morris were among the second generation of SLATE activists and joined the group around the same time in 1960 – after the famous HUAC protest in May of 1960 and before the Free Speech Movement in 1964. They also have similar upbringings in Jewish (adoptive family, in Griffin’s case) and politically left families who feared encroaching McCarthyism. These backgrounds helped ignite a political consciousness in both women that led them to SLATE.

Griffin and Morris’s oral histories build on an archive of SLATE history, but they also speak specifically to their experiences as women in this group. Both recount instances of feeling marginalized as women, of being left to do the “scut work” like mimeographing and cooking for hungry activists. They even recount tensions at a 1984 SLATE reunion in which those newly empowered by feminism expressed displeasure with the way they had been treated; many of the men denied this discrimination, but others took it to heart and sincerely apologized. And yet, Griffin and Morris both were encouraged to run for ASUC office in the early 1960s, campaigning on the SLATE platform and often pushing their own boundaries of what they thought was possible. Despite the challenges of being a woman in this campus political group, there were still opportunities to grow as individuals and as leaders.

Listen as Susan Griffin and Julianne Morris share their memories of running for ASUC on the SLATE ticket at UC Berkeley:

Even though both Griffin and Morris had decreased participation in SLATE or left campus by 1964, their experiences in the organization clearly shaped their perspectives about politics and activism, particularly as they both became involved with the women’s movement. Griffin explained, “The guys may not have known it, but they were training feminist activists in all that period.”

Most importantly, by recalling their times with SLATE and later political work, both Griffin and Morris emphasized the importance of building and sustaining community in activist groups. For Morris, joining SLATE helped her find a place where she belonged. Griffin pointed to organizations of politically like-minded individuals as ways to create belonging and “joy” through an almost spiritual experience of protest.

Listen as Julianne Morris reflects on SLATE’s impact on the Free Speech Movement:

Come learn more about SLATE, and explore the oral histories of Susan Griffin and Julianne Morris!