Bancroft Library

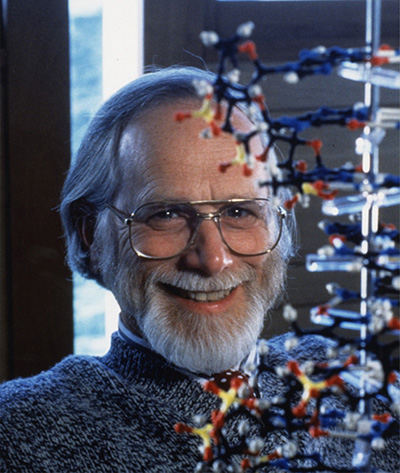

J. Michael Bishop: Scientist, UCSF Chancellor, and Nobel Laureate

This oral history with J. Michael Bishop is one in a series documenting bioscience and biotechnology in Northern California. Selecting Rous sarcoma virus, a cancer-causing retrovirus, after arriving at UCSF in 1968, Bishop was soon joined by Harold E. Varmus with whom he established a partnership legendary for its length and productivity. In a seminal publication of 1976, they established the proto-oncogene as a normal cell component and precursor of oncogenes. In 1989, Bishop and Varmus were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for this research. With some reluctance, Bishop agreed to become UCSF Chancellor in 1998. His highly productive eleven years saw the creation and staffing of the Mission Bay campus and record-breaking fundraising success, among other important events he oversaw. The oral history consists of five interviews conducted in 2016 and 2017, with an introduction by colleagues Bruce Alberts and Harold Varmus.

Bancroft Welcomes Digital Project Archivist

Please join us in welcoming Lucy Hernandez as our new Digital Project Archivist on the NPS-funded Japanese American Confinement Sites (JACS) grant project. Lucy will manage the two-year JACS project to digitize materials from Bancroft collections related to the Japanese American Internment. She will begin her new appointment on Monday, May 15.

Lucy comes to us from her position as the Archivist at The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art in Sarasota, Florida where she worked on processing, digitizing, and providing reference services for archival collections. Prior to that, Lucy worked as the Archivist at the Tom & Ethel Bradley Center, California State University, Northridge for 10 years.

She earned her Bachelor of Arts in Economics and Art History from University of California Santa Cruz and a Masters of Arts in Art History from California State University, Northridge, and she is certified by the Academy of Certified Archivists.

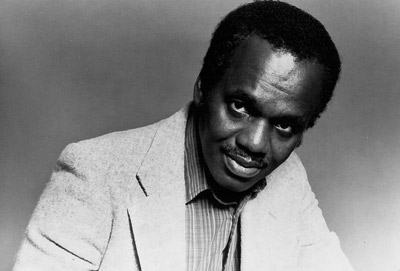

In Memory of Gildo Mahones (1929-2018)

Today we commemorate the life of Gildo Mahones, an inspiring, talented, and powerful bop-based pianist who grew up in Harlem in the 1930s and 40s and played with virtually all the jazz greats during the 1950s and 60s. He passed away last week at the age of 88. His 2015 oral history addresses a plethora of issues surrounding jazz: his childhood in Harlem, the advent of bebop and its luminaries, jazz vocalism, racism, and more.

Mahones was born to Puerto Rican parents in the Spanish section of East Harlem in 1929. Later the family moved to an apartment behind the Apollo Theatre, and in the 1950s, he eventually performed with many of the jazz greats he heard there as a teenager, including Duke Ellington and Count Basie. In a Berkeleyside feature of Mahones, writer Andrew Gilbert describes how the pianist and the piano were not love at first sight; after an unsuccessful first lesson at age seven, it took his mother moving the neighbor’s left-behind piano into their home and a family friend doling out some live tunes on the piano for Mahones to finally warm up to the instrument.

After being hired to perform in 1949 at Minton’s Playhouse in Harlem and then briefly serving in the military, Mahones became the pianist for Lester Young’s band at Birdland. Here, he wrote dozens of songs. On composing, Mahones said in his interview, “Oh, the songs come to me in many ways. […] A dream could blossom into a song.” He goes on to describe Young’s unique style of playing and his friendship with Billie Holiday, whom he dubbed Lady Day and who called Young ‘Prez’.

In 1965, Mahones moved to Los Angeles to work with Joe Williams and Harry “Sweets” Edison at the Pied Piper club, also working with vocalists O.C. Smith, Lou Rawls, James Moody, Big Joe Turner, and Lorez Alexandria, with whom he recorded several albums. Throughout the 1970s, he was a popular sideman in clubs across Southern California, and toured Japan and Europe with Benny Carter and with his own band. Mahones has several recordings published with a Japanese company, which unfortunately have not been released in the US. Later on, he and Mary, his wife of 45 years, moved to Oakland so as to be near their daughter and grandson. He practiced often and performed at clubs and galleries around the Bay Area.

You can hear more of Mahones’ reflections in this video excerpt from his oral history.

The Bancroft Library Announces New Head of Technical Services

After an extensive national search, the Bancroft Library is pleased to announce the appointment of Mary Elings as the Head of Bancroft Technical Services and Assistant Director of The Bancroft Library. In this role, Elings will provide leadership for Bancroft’s largest division responsible for technical services operations for rare books, archival, and special collections as well as for the use of advanced technology to establish administrative and intellectual control over Bancroft collections.

Before taking on this role, Elings served as the Interim Head of Bancroft Technical Services from 2016 to 2017. Prior to that, she held the position of Bancroft’s Principal Archivist for Digital Collections and served as Head of the Digital Collections Unit. Elings began her career at Bancroft in 1996 as a pictorial archivist before expanding her expertise in operational support for public services, archival information systems, digital research collections, and born-digital archives. Her leadership in developing digital research collections has not been limited to Bancroft but has also served the University Library, the Berkeley campus, and the University of California system. Her teaching in the field of librarianship, as adjunct faculty for library and information science schools at Catholic University in Washington, D.C., and Syracuse University in New York, has enhanced her leadership in this area. Her current research focus is on developing “research ready” digital archival collections in support of computational research needs and working with faculty and students on collaborative research projects in the digital humanities.

Elings succeeds David de Lorenzo, who served as the Head of Bancroft Technical Services from 2001 until 2016 when he was appointed the Giustina Director of Special Collections and University Archives at the University of Oregon.

Elings can be contacted at melings@berkeley.edu.

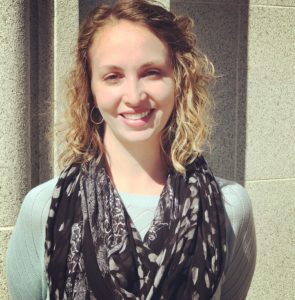

Join Us in Welcoming Amanda Tewes!

We are pleased to welcome Amanda Tewes to the Oral History Center. Amanda joins our team as an Historian/Interviewer.

We wanted to get to know her a little better, so we did what we do best: asked her a few questions.

Q: When did you first encounter oral history?

A: I first encountered oral history almost ten years ago as a graduate student at Cal State Fullerton. Oral history was an important part of the coursework for the public history program. After I completed work on my first exhibit about Marine Corps Air Station El Toro and a changing mid-century Orange County, California,, I realized how much the oral histories featured in the show resonated with visitors; the oral histories made history personal and understandable. Oral history has been part of my historical toolkit ever since.

Q: How did you use oral history in your graduate work?

A: Oral history played a key role in my dissertation. Oral history played a key role in my dissertation, Fantasy Frontier: Old West Theme Parks and Memory in California, which highlighted three Old West theme parks in California. I knew I wanted to study Old West theme parks in California, but the more research I did the more I realized that this was as much as story about memory and regional identity as it was about fictional representations of the past and the history of the parks themselves. Historians often have a hard time explaining why someone did something in the past, but conducting oral histories for this project opened a

window into the deep personal and ongoing connections individuals have to these theme parks, as well as helped answer the why of it all–why these parks were created, why they still exist (or don’t), and why they continue to matter.

Q: Which interviewers have been your biggest influences, either in or out of oral history?

A: I listen to a lot of podcasts and talk radio. I appreciate interviewers who are quickly able to build rapport with their guests and who can think on their feet to ask poignant follow-up questions. I think Terry Gross does this really well. She also has an uncanny ability to put her guests at ease and to elicit honest and personal reactions.

Q: What projects are you most excited to work on at the OHC?

A: I am really looking forward to working on the oral history project in collaboration with the Getty Trust. Not only is this a fascinating organization with a storied past, but the project will also bring me back to my art history roots.

Q: What is your dream oral history project?

A: Right now my dream oral history project is one that explores politics and activism in California. Political leadership and organizing in California has and continues to have important implications nationally, and I hope to work on a project that expands the Oral History Center’s impressive collection of interviews about politics in the Golden State.

A Valentine’s Day throwback: Love in our letters

In 1922, Firgie Todd wanted to make a shirt for her boyfriend, Charlie Smith. Todd had forgotten to take Smith’s measurements the last time she’d seen him, however, and the two lived far apart, on opposite ends of Humboldt County, California.

But Todd, a clever woman, had a plan.

“I do not suppose you have a tape measure,” wrote Todd in a Dec. 11, 1922 letter. “So I shall enclose a piece of string, and you please cut it off the length of the inside seam.”

The charming correspondence can be found in a box of material on the family of James Samuel Todd — a Presbyterian minister who moved to California in 1868. Firgie Todd was James Todd’s granddaughter, and hers is one of many love letters living in The Bancroft Library.

The letters, which go back to at least 1851, when the California Gold Rush tore many a lover apart, document the quirks and pains of love through war, separation, and cultural strife. In a pre-digital, largely pre-automobile world, the letters show the resolve and resourcefulness of long-distance relationships, kept alive through streams of affection and babble. In many cases, letters traveled between lovers as if on a merry-go-round, coming and going precisely each week.

And so, for the lover in you this Valentine’s Day, here’s some inspiration from lovers past, pulled from the troves of the Bancroft collection. The quotes are grouped by common themes that reflect the sentiments of nearly 120 letters between seven pairs of lovers.

1. It’s always darkest before the dawn

“When I cast my eyes over the much-valued lines of your letters, I can almost imagine that Carrie is near me. I can hear her sweet and gentle voice. It leads me to ask myself how long will it be before I shall have the pleasure of seeing you. O, may the time be as fleeting as the tears of an infant.” — James J. Bxxxx, who signed his name like that, writing from Drayton, Georgia, on March 21, 1856 to a woman named Carrie.

“I am waiting for the day when you will be telling me that there is too much pepper and not enough salt.” — Eva Weintrobe to Morris Davis on March 3, 1938.

Weintrobe worked as a seamstress in Liverpool. The couple wrote back and forth for a year — breaking up once or twice over some hastily written letters — until Weintrobe left her family in England to marry Davis, an American in New York.

“I, who kept on telling you to think of the future whenever the loneliness of the present would sadden you, I feel depressed and disheartened a la folie. … Don’t scold me for it Lily — It is only a passing weakness, and will be short-lived. … [T]here is a balm for my ailment, and that is the very first of your cheering smiles,” wrote Nathan Edelman to future wife Lily Pokvidz on Sept. 7, 1931. Pokvidz, an author and educator, was born in San Francisco and lived in Petaluma during the couple’s courtship. Edelman was studying languages at the time and became an expert in French literature. They often worried that Edelman would be drafted to fight in World War II.

2. Dating without a cellphone could get a little ridiculous

In 1943, a young man named Robinson Jeffers often snuck into the bedroom of Connie Flavin Palms, in Carmel, California. Their secret meetings were arranged on scraps, folded into pieces no larger than a finger, and exchanged at various meeting points:

“I must see you — I must. Nothing can prevent us from having an hour together sometime. I was thinking — if I knew where your room is — I’d climb up and scratch on your window — some night at 3 a.m. — it would only take two hours to walk there — and you’d let me in — so beautiful but a dream. I love you forever. …

“Telephone before 10 p.m. if possible. If someone else answers, ask her to tell me that you saw Pigeon Point light from here — and I’ll look for you at 11. Or, say New Year’s Point light, and I’ll look for you at three. I love you. I love you. I love you.”

3. Distance makes the mind go crazy

3. Distance makes the mind go crazy

“I’ll never be whole till you return to me, I must have you at my side, with me, around me, in me … the present remains incomplete without you; music, which I adore, sounds flat … yes! even Gilbert and Sullivan! — sound frivolous.” — Nathan Edelman to Lily Pokvidz on Sept. 7, 1931.

“Darling, there is no one like you in all the world — every gesture beautiful, and every inflection of your voice and movement of your mind. I think of you every instant — really — day and night — don’t you feel it? It is very hard not to be able to see you, and hear you, and touch you. … The night is wild/With stars but ours/Has not risen yet/Some might it will/— sometime soon —/I hope I don’t go/Mad first.” — Robinson Jeffers to Connie Flavin Palms, 1943 (date unknown).

4. Letters were essential, and people got salty over delays

“What made you think I was sore with you about something? If it was because I did not answer sooner, I want you to know that I am not a person of leisure and have not much time for letter writing. … You asked me again why I do not write more sentimental and intimate letters. I am not a poet and cannot express my feelings in black and white and feel I will not be doing justice to my feelings.” — Eva Weintrobe to Morris Davis, April 10, 1936.

“When you will write, I shall feel once more in contact with you — but you must write me all your thoughts and share all your emotions with me; you must let your pen run as if your mind; free and open, were expressing itself without any restraint whatever; I wish to feel you through your letters, and by adoring the Lily I shall divine between the lines, I will find a year’s waiting more bearable.” — Nathan Edelman to Lily Pokvidz, Sept. 7, 1931.

“I’ve read and read your precious letter — it’s the strangest thing how the older we get, the harder I find our separation, no matter of how short duration. To bear, I clutch at every scrap of letter to shorten the gaps and narrow the distances.” — Lily Edelman to Nathan Edelman, Jan. 1, 1943.

“Dear Carrie, I anticipated an epistle from the last mail, but was sadly disappointed. You can not imagine my feelings when I called at the office. … No letter from Carrie, one that I love.” — James J. Bxxxx to Carrie, April 18, 1856.

5. If you liked it then you should’ve bought a house for it

“You don’t know how I long to see you to hold you in my arms and call you my own but I don’t know when that will be again. Money is what I want for I know I have got to have that before I can claim you. … I shall not come until I can offer you a home, and I presume you will be married before that time comes for it will be years before I can do that, and you will get tired of waiting.” — A man named Ralph, writing from Corning, California, to Myrtie on March 9, 1880.

6. Late night letter writing could get a little PG-13

“Never can I forget the ecstatic thrill of thy sweet kiss or the rapture of folding thy lovely form to my bosom.” — Gold miner Alfred to his fiancee, Orpha, on Aug. 7, 1851.

“Well dearest it is now ten o’clock and I must get my bath and get to bed, for tomorrow is another day. If my darling girl was with me tonight ten o clock would be quite early, even two o’clock in the morning was early sometimes.” — William H. Staniels Jr. writing to fiancee Marianna Monkhouse on Sept. 29, 1920. (The couple fell in love in Berkeley, spending most days in nature. They were engaged six weeks after meeting.)

“As much as I should like to travel the world over, like a master of the planet, I could forget that yearning, in your presence. With your hand in mine, and a deep, soulful kiss from you, and with you next to me everywhere, in everything, I would have the bliss of an eternity.” — Nathan Edelman to Lily (Pokvidz) Edelman, early to mid-1900s.

7. Love painted adversity in rose gold

7. Love painted adversity in rose gold

In 1851, a man named Alfred moved to Iowa City, California, to work in the mines during the height of the Gold Rush. Here’s an excerpt from a letter to his fiancee, Orpha, written Aug. 7, 1851:

“Amid all the disappointments and vexations of California life, I have still the same unimpeachable assurance that there is one that loves me. … And my greatest study now is to make myself worthy of that love. Come what may I hope at least to have an honest heart to give in return. …

“I wanted to send you enough to do your little fix me up, but expenses since I have been here have taken all the money I had so I can’t help it without borrowing, and that I dislike. … I must ever admire the expression of yours, about wealth, that the ‘wealth of a cottage is love.’ Well then, Dearest Orpha, we may be wealthy if I should make nothing by this long sojourn in California. But still I believe that I will make a few hundred dollars here. … [T]he boys all say that we will make from five hundred to two thousand here, but how little we know. …

“I believe this letter is the poorest one that I have written in California. My excuse is that I have worked very hard for five weeks past and now my hands are so badly bruised that I can’t hold a pen. But you know one thing, that it comes from one whose heart is yours until death.”

NHPRC Supports Processing Environmental Collections at The Bancroft Library

The Bancroft Library is currently engaged in a two-year project funded by the National Historical Publications and Records Commission to process a range of archival collections relating to environmental movements in the West. A leading repository in documenting U.S. environmental movements, The Bancroft Library is home to the records of many significant environmental organizations and the papers of a range of environmental activists.

Among the library’s environmental holdings are the records of the Sierra Club, including correspondence of naturalist and Club founder John Muir, the records of the Save-the-Redwoods League, and the records of Save the Bay. Among the collections already made available to researchers in this current NHPRC-funded project are the records of the Coalition for Alternatives to Pesticides, the records of the Small Wilderness Area Preservation group, the papers of environmental lawyer Thomas J. Graff, and the records of California-based Trustees for Conservation. Collections scheduled to be processed in the next eighteen months include the records of such major environmental organizations as Friends of the River, Friends of the Earth, the Rainforest Action Network, and the Earth Island Institute.

The Berkeley Remix: Season 3 of the Oral History Center’s Podcast

Listen to Season 3 Episode 1 of our podcast now known as The Berkeley Remix.

This podcast is about the politics of the first encounters with the AIDS epidemic in San Francisco. The six episodes draw from the thirty-five interviews that Sally Smith Hughes conducted in the 1990s. A historian of science at UC Berkeley’s Oral History Office, Sally interviewed doctors, nurses, researchers, public health officials and community-health practitioners to learn about the unique ways that people responded to the epidemic. Although these interviews cover a wide range of topics, including the isolation of the virus HIV and the search for treatments, the interviews we selected for this podcast are more focused on public health, community engagement, and nursing care. Most of the following podcast episodes are about the period from early 1981, when the first reports emerged of an unknown disease that was killing gay men in San Francisco, to 1984 and the development of a new way of caring for people in a hospital setting.

Episode 1 explores what it was like to be gay in San Francisco in the 1960s and 70s, before people became aware of the epidemic.

Visit The Berkeley Remix for release of Episodes 2-6 each Wednesday.

Remembering Gene Brucker (1924-2017) and the Department of History Oral History Project

Remembering Gene Brucker (1924-2017) and the Department of History Oral History Project

We note with sorrow the passing in July of Professor Emeritus Gene Brucker, historian of Renaissance Florence, one of our esteemed oral history narrators, and the instigator and longtime supporter of our oral history series on the Department of History at Berkeley.

The oral history series had its beginning in 1995, when Gene was designated as the Faculty Research Lecturer. Instead of focusing his lecture on Renaissance Florence, he turned his historian’s eye on Berkeley, on his own department, where he had arrived in 1954 in time to participate in its postwar flowering into one of the most distinguished history programs in the US. In his research he found few remaining written records; surprisingly, the department had discarded a great deal of its own history. He turned to informal interviews with his colleagues to develop his lecture. Later discussion with his friend Carroll Brentano, historian of the University of California and wife of Gene’s colleague, Robert Brentano, led to the idea for an oral history project under the auspices of the Regional Oral History Office, predecessor to OHC. I was fortunate to work with them as the project director and interviewer. For over a decade Gene and Carroll served as project advisors. They convinced their colleagues to themselves become subjects of historical research, and they facilitated the funding that made the project possible.

Among our wealth of oral histories on the University of California, OHC’s series on the Department of History at Berkeley stands out. With lengthy biographical oral histories of nineteen professors of European, American, and Asian history, and one faculty wife, all of whom came to Berkeley in the late 1940s to the early 1970s, it the most extensive of our several series on university departments. And thanks in great part to the vision of Gene Brucker, the interviews are extensive in scope as well: along with a deep dive into the personal background, education, and scholarly trajectories of each narrator, they discuss postwar departmental history in some detail, including governance, key hiring and promotion decisions, curriculum and teaching. And they examine Berkeley’s academic culture, the informal and formal associations and interactions that invariably affect scholarship. They also explore the involvement, often intense in this postwar generation, in broader campus governance and major campus controversies from the loyalty oath, free speech, and antiwar protests to the belated hiring of women faculty in the 1970s.

Having contributed so much to the project, Gene Brucker, a man who really did not like to talk about himself, finally agreed, reluctantly, to record an oral history in 2002. I met with him for eleven sessions, documenting his journey from farm boy in Cropsey, Illinois—via the University of Illinois, Oxford, Princeton, and the Florentine archives—to a career as a distinguished historian of Florence and preeminent citizen of the Berkeley campus. Like others in the series, it is replete with insights into academic culture, the historians’ craft, and the postwar years of growth and tumult on the Berkeley campus. Gene’s oral history and others in the Department of History project. See also “In Memoriam: Gene Adam Brucker”

Ann Lage, interviewer emeritus, October 24, 2017.

In Memory of Ruth Bancroft 9/2/1908 – 11/26/2017

UC Berkeley alumna Ruth Petersson Bancroft, founder of The Ruth Bancroft Garden in Walnut Creek and well-known expert in dry gardening, passed away at the age of 109 on Nov. 26. Her oral history, The Ruth Bancroft Garden in Walnut Creek, California: Creation in 1971 and Conservation, conducted in 1991 and 1992, is described by interviewer Suzanne B. Riess as “…the amazing chronicle of the growth of a passionate gardener, from her childhood recollections of spring wildflowers on the hills of an earlier, bucolic Berkeley, to her current triumphs, and the tribulations of stewardship of a garden more or less in the public trust.”

The daughter of first-generation Swedish immigrants, Ruth Petersson was born in Massachusetts, but moved to Berkeley, California when her father landed a professorship at UC Berkeley. Of her childhood, she said, “I spent a lot of time wandering around and also over into Wildcat Canyon, just looking at the wildflowers and I think that’s what started me in the interest of wildflowers…” Although Ruth originally studied architecture as one of the only women in the program at UC Berkeley, the Great Depression hit and so for the sake of job security, she switched her career to education. It was during her time as a teacher of home economics in Merced that she met Philip Bancroft, Jr., the grandson of Hubert Howe Bancroft, whose 60,000-volume book collection began the Bancroft Library. After they married, the couple moved onto the Bancroft Farm in the East Bay. The Bancroft family sold much of their land to the city of Walnut Creek as it expanded over the years. Later, in 1971, Philip Bancroft, Jr. gave the last 3-acre plot of walnut orchards to his wife in order to house her extensive collection of succulents.

Though The Ruth Bancroft Garden now boasts a beautiful display of water-conserving plants, the garden was not without its hardships at the beginning. Just a few months after Bancroft began her garden, a severe freeze in December killed nearly all that she had planted. Still, she persevered. “Well, I started again the next year… I figured it doesn’t happen that often, and you can’t just not replant those same things, because they might have another twenty years before they’d be killed again. So I’m just replanting. Have to start over again.” To this, Riess queried, “You didn’t think in some way you had been given a message?” Bancroft laughed and replied, “No.”

A long-time friend of Bancroft and former manager at the UC Berkeley Botanical Garden, Wayne Roderick said, “I would classify Ruth as a genuine dirt gardener. She’s out there doing things with her bare hands. She would be out in the garden by seven at the latest, and for the first hour she was weeding the path of the little spotted spurge, hand-weeding those paths until her knees would get so sore from the rocks, the gravel. That’s what I mean by a genuine dirt gardener.” In addition to Bancroft’s hands-on style of working, she also kept meticulous records as she created her garden. An invaluable addition to her oral history is the transcription of the entirety of her handwritten notes on the garden’s first year, cataloguing every trial and triumph. Riess urges in her introduction to the oral history, “Any gardener will do well to read that year of Ruth’s journal, to see the value of a journal, as well as the work involved in realizing a dream, and the necessity of being willing to weed!”

Over the years, Bancroft also had many helpers that contributed to the development of her impressive creation, such as Lester Hawkins, who created the original design of the garden, and her husband Philip. Roderick recalls, “Phil Bancroft just adored Ruth, and he wanted her to have anything she wanted. He did everything he could to help her. I don’t think Phil thought about the garden continuing, but he certainly was there to make sure she got what she wanted for the place. He was a farmer-type, but he enjoyed seeing the garden, and he was willing to get in and help.” Later, her garden would inspire fellow gardener Francis Cabot to create the Garden Conservancy, of which the Ruth Bancroft Garden became the first of many private gardens to be preserved for the public.

Still, through all of the international recognition and acclaim she received, Bancroft maintained a simple and genuine love for gardening: “You never know just what’s going to bloom when, during the summer. And a lot of the bloom just lasts a day, or possibly two days. It’s interesting to see what there is, and catch it before it’s gone.” When asked whether she had had a mission for the garden, she replied, “I just started it for the fun of it, and the enjoyment of it. I had no idea that people would be looking at it, no idea at all.“

Maggie Deng

Oral History Center Student Assistant