Bancroft Library

New Oral History: MaryAnn Graf, “The Life of a Wine Industry Trailblazer”

We are pleased to release our oral history interview with MaryAnn Graf. MaryAnn Graf was the first woman to graduate the University of California Davis in Food Science with a specialization in Enology, which she did in 1965. She went on to work for commercial wine operations such as Gibson and United Vintners before being hired as winemaker for Simi Winery in 1973.

After leaving Simi, she established with Marty Bannister the company Vinquiry, which provided laboratory and wine consulting services to wineries throughout California. She retired from Vinquiry in 2003. In this oral history, Graf discusses her upbringing in California’s Central Valley, her undergraduate education at UC Davis, her early jobs formulating flavored wines, her move into varietal wines at Simi and work with leaders including André Tchelistcheff, and her establishing a consulting wine laboratory. She also discusses her unique position as a woman in the wine industry at a time in which most every job was dominated by men.

This interview with MaryAnn Graf represents just our most recent interview on the California wine industry, which has been a major focus of the Oral History Center for many decades. We are excited to report that more fascinating interviews in this area are currently in production and we are actively seeking partners who might help us by sponsoring more interviews. Please contact OHC director Martin Meeker for more information: mmeeker@library.berkeley.edu

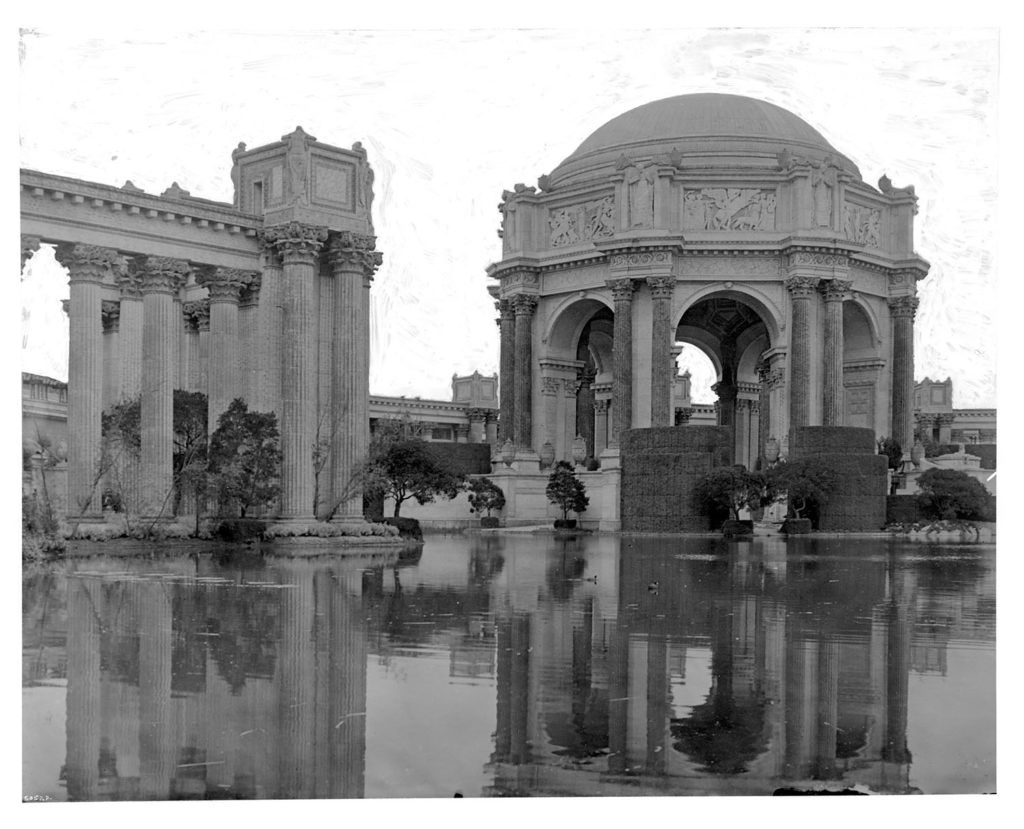

Now Online: Images from Glass Negatives of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition

The Bancroft Pictorial Processing Unit is proud to announce that The Edward A. Rogers collection of Cardinell-Vincent Company and Panama-Pacific International Exposition Photographs has been organized, archivally housed, individually listed, and made (substantially) available online. This work was accomplished over two years, thanks to grant support from the National Endowment for the Humanities and, of course, careful hard work on the part of many library staff.

In this blog posting, Project Archivist Lori Hines describes some of the most challenging (and rewarding) work; preserving and providing access to fragile and often damaged glass negatives.

Handling Glass Plate Negatives: A Lesson in Mindfulness

The Rogers collection of Panama Pacific International Exposition photographs, received as a gift in 2014, includes over 2,000 glass negatives. These fragile items required special handling and archival containers with padding. Hardest to work with were approximately 150 oversize glass negatives ranging from 11 x 14 inches to 12 x 20 inches. Antique glass can become brittle and, of course, is heavy. From handling to wheeling the negatives back and forth to the conservation department and the digital lab, one had to be very conscious of every move and step taken.

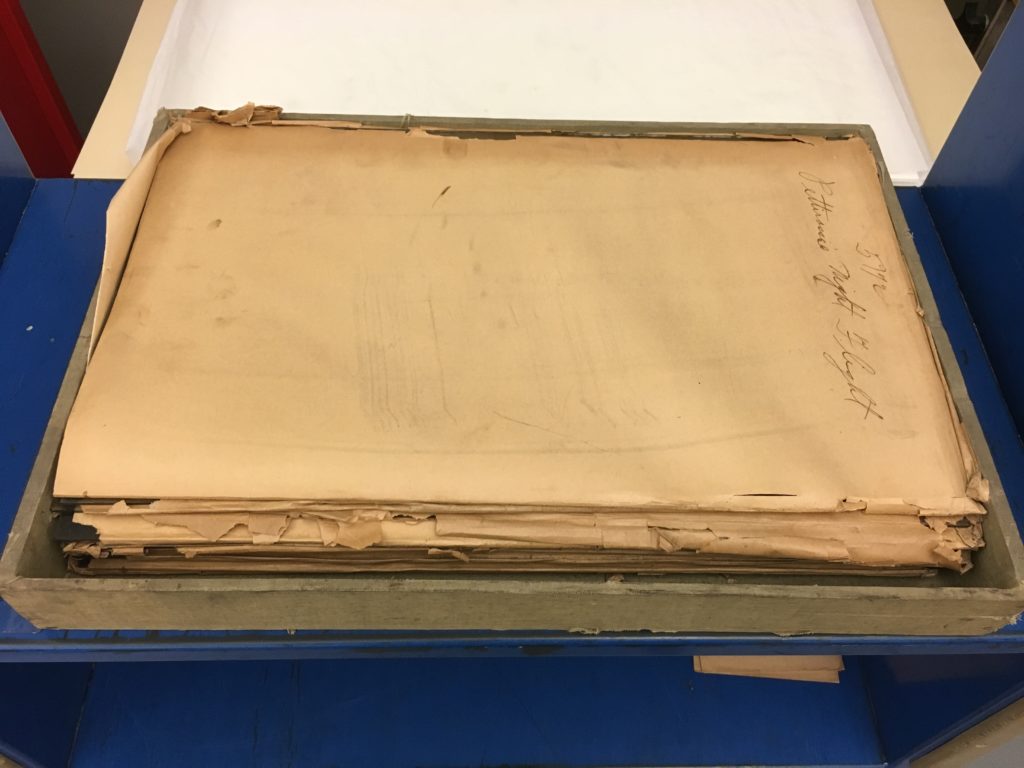

This first photo shows how the negatives were received in the library. Note they have no padding between the plates and there are only original, brittle sleeves to protect them. A stack of ten or fifteen is very heavy and getting your fingers under one, to lift it off the stack, is challenging. The weight of the negatives on top of each other is also a risk — the antique glass can easily crack under the weight.

This photo shows how the negatives have been housed by library staff; vertically with corrugated archival cardboard around each. Our library conservators designed the housing to limit box weight, to provide protective padding, to protect the plates from abrasion as they’re removed, and to make handling safer.

The largest plates, at 12 x 20 inches, needed another housing solution because it was impractical to store them upright, but the weight of one on another was a concern. The Library’s Conservation Department built custom trays to hold each 12 x 20 negative, with just three plates (and their trays) in an archival box that is stored flat on a cabinet shelf.

The negatives are handled on the long side of the glass to offer best support and, during the cleaning, housing, and inventory process, are rested on a piece of thin foam padding to buffer any impact with the work table.

About 10% of the negatives arrived broken. To be digitized, we had to re-piece the broken negatives together on a supporting sheet of glass, like a puzzle, then hand it off immediately to the photographer in the Library’s Digital Imaging Lab. The glass sheet with the broken negative on top was then placed on a light table, so it was lit from behind, to be captured by the digital camera. The light table and camera are visible in the background of this image.

The results were often quite satisfying, as can be seen in this example of a badly broken glass negative that was pieced together.

The finding aid describing and listing the entire Rogers collection, with more than 2,000 digital images, may be viewed at the Online Archive of California.

To browse examples of images scanned from broken plates, try searching the finding aid for “negative is broken”, and navigating through the results, or by browsing this Calisphere website search that retrieves just the broken-plate images.

Special thanks go to Christine Huhn and the staff of the Digital Imaging Lab; Hannah Tashjian, Erika Lindensmith, Martha Little, and Emily Ramos of the Conservation Department; staff of the Library Systems Office and the California Digital Library that worked with us to get the material online; to Gawain Weaver Art Conservation (contractors for preservation and scanning of panoramic film negatives), and to the Bancroft Pictorial Unit team that devoted much or their 2016-2018 work life to this effort: Lori Hines, Lu Ann Sleeper, and a crew of student staff.

WILLIAM REESE: A MAN WHO LOVED AMERICANA

by Steven Black, Bancroft Acquisitions

In quick succession, joy followed by tears, June 2nd and 4th, 2018.

At the Annual Meeting of The Friends of The Bancroft Library, Carla A. Fumagalli was introduced as this year’s awardee of the William S. Reese Fellowship in American Bibliography and the History of the Book in the Americas.

For a number of years Bancroft has been favored to host a Reese fellowship, along with other peer institutions, including American Antiquarian Society, the Beinecke library at Yale University, the John Carter Brown library at Brown University, the University of Virginia Library, the Huntington Library, the Bibliographical Society of America, and the Library of Congress .

Two days later news reached us of the passing of William Reese, one of the foremost U.S. antiquarian booksellers and bibliographers of our time.

Celebration, punctuated by grief and mourning, then, hopefully, more celebration (if not stoic acceptance) —is a rhythm we accept without relish. Closer to home, our mortal persistence was tested in February with the passing of eminent Berkeley bookseller, Ian Jackson, who was a familiar presence to many on the UC campus and in bookshops around town.

Bancrofters most recently saw Bill Reese in February at the California International Antiquarian Book Fair in Pasadena.

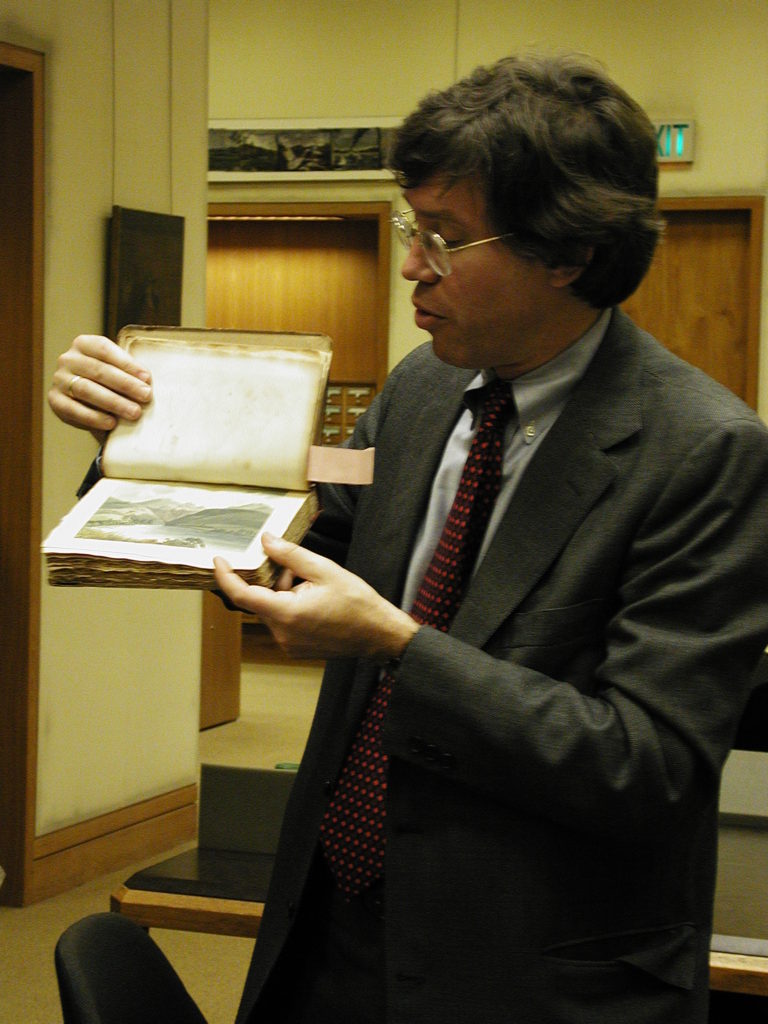

Looking back on decades of our working together to build the Bancroft Collection of Western Americana, brought to mind a special visit he made to the Library in February 2001. His talk was about major and minor colorplate travel and exploration books on the American West, using a small selection assembled for display on that occasion.

Here are some pictures of this informal exhibition, after hours in Bancroft’s Edward Hellman Heller Reading Room.

Join Us in Welcoming Roger Eardley-Pryor!

We are pleased to welcome Roger Eardley-Pryor to the Oral History Center. Roger joins our team as an Historian/Interviewer.

We wanted to get to know him better, so we gave him our Q&A treatment. For more, follow him on Twitter @Roger_E_P.

Welcome, Roger!

Roger Eardley-Pryor

Q: When did you first encounter oral history?

I first encountered oral history in the Spring of 2011 at the Science History Institute (formerly Chemical Heritage Foundation) when doing archival research there as a graduate student. Rows and rows of hard-bound transcripts from their oral histories with leading chemists lined the shelves of their library in Philadelphia’s historic Old City. At that time, I focused on the dusty boxes pulled from their traditional archives. But those oral history interviews sparked my curiosity. Years later, after completing my PhD at the University of California Santa Barbara, I accepted a post-doctoral fellowship in the Science History Institute’s Center for Oral History. I conducted oral histories for their collection that, I hope, spark the interests of future researchers there.

Q: How did you use oral history in your graduate work?

While writing my dissertation, I drew from oral history interviews conducted by the United Nations Intellectual History Project (UNIHP) based out of the Ralph Bunche Institute for International Studies at CUNY. My dissertation analyzed the “global environmental moment” created by the 1972 United Nations Conference on the Human Environment, held in Stockholm, Sweden. The clashes between ecological scientists, international diplomats, and environmental activists in that moment laid the foundations for what later became sustainable development. But those clashes also entrenched the political patterns that still hamstring today’s efforts to solve global environmental challenges like climate change. The seventy-nine oral history interviews from the UNIHP offered first-hand accounts from UN diplomats, some who attended the Stockholm Conference and others who later defined the concept of sustainable development.

Q: Which interviewers have been your biggest influences, either in or out of oral history?

I love Terry Gross’s interviews on NPR’s Fresh Air. Even before I lived in Philadelphia, where Terry Gross lives, I’ve considered her an American treasure! In addition to solid research before her interviews, she has a knack for personal rapport with her narrator and her listeners. She goes beyond the particulars of past events and encourages narrators to share their feelings about those events, often in light of the narrator’s earlier family experiences. She, her narrators, and her listeners all seem to enjoy and learn something new from her interviews.

Q: What projects are you most excited to work on at the OHC?

I’m super excited to work on a renewed Sierra Club project at the OHC! I’m also co-developing with Shanna Farrell an oral history project about the intersecting communities surrounding EPA Superfund sites. And I’m keen to work with Paul Burnett on a project exploring Gender and Diversity in Silicon Valley.

Q: What is your dream oral history project?

An oral history project commemorating the first Earth Day would be dreamy! Earth Day was a nation-wide environmental teach-in held on April 22, 1970, which celebrates its 50th anniversary in 2020. Part protest and part celebration, Earth Day 1970 saw an estimated 20 million Americans at roughly 1500 colleges and 10,00 primary and secondary schools across the country organize their own particular Earth Day teach-ins and demonstrations. This unprecedented activity proved transformational for life-trajectories of many Earth Day participants and significantly effected legislative policies at local, state, and federal levels. In my wildest dreams, I imagine an Earth Day oral history project that reflects the original organization of Earth Day. I envision oral historians and institutions partnering to conduct interviews all across the nation but focused on the Earth Day stories and environmental legacies of their particular locations. I imagine high schools and colleges hosting 50th Anniversary Earth Day meet-ups for original participants to gather and record their own memories of Earth Day, which could be uploaded and digitally archived at a central organizing institution, perhaps through the Bancroft Library’s Oral History Center! I imagine hosting more formal and polished “Oral History Live” events where project interviewers re-create/re-visit some of the most interesting stories from interviews on stage with their narrators, which would be live-streamed online. At these live events, narrators could share their perspective on Earth Day’s legacies, reflect on changes since, and address new or unresolved environmental issues that demand attention and action.

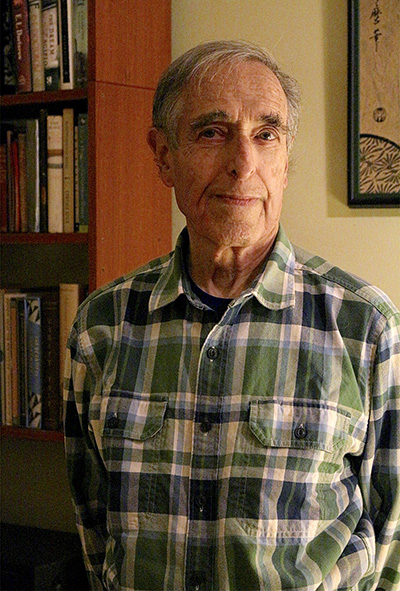

Michael B. Teitz: Fifty Years of Planning and Policy, from U.C. Berkeley to the Public Policy Institute of California

Michael B. Teitz is Professor Emeritus of City and Regional Planning at the University of California, Berkeley. He is also a Senior Fellow and Director of Economy at the Public Policy Institute of California, which he helped establish. In addition to a distinguished, thirty-five year career at UC Berkeley, and policy work that still continues at PPIC that still continues, he has served as a consultant to local, state, and national governments, both in the United States and Internationally. In this interview he discusses growing up in London during and after World War II; Coming to the United States for graduate school; the various events and changes he experienced at UC Berkeley between 1962 and 1998; developments in the fields of Planning and Regional Science; his consulting work for local and state governments in the U.S. and Saudi Arabia; and leaving Berkeley to establish PPIC and serving as its founding Research Director.

Out from the Archives: Rosalind Wiener Wyman

Out from the Archives: Rosalind Wiener Wyman

“They couldn’t believe that I could win,” Rosalind Wiener Wyman remembered about her unexpected election to the Los Angeles City Council in 1953. Over the course of several interviews in 1977 and 1978, Wiener Wyman shared her personal and political triumphs and losses, which culminated in her oral history, “It’s a Girl”: Three Terms on the Los Angeles City Council, 1953-1965; Three Decades in the Democratic Party, 1948-1978. Wiener Wyman’s memories as a woman politician at midcentury are part of the Oral History Center’s California Women Political Leaders Oral History Project, which documented “California women who became active in politics during the years between the passage of the women’s suffrage amendment and the…feminist movement.”

Wiener Wyman came by her passion for politics honestly. Speaking of her parents, she reflected, “I always felt their activities and interest in politics was steeped in me. In my baby book, at two, I’m looking up at a picture of FDR [Franklin Delano Roosevelt]. Most kids in their baby book are not looking at posters of FDR.”

While a student at the University of Southern California, Wiener Wyman and the campus Democratic Club worked on Harry Truman’s 1948 campaign. But her political work began in earnest when she met her “heroine,” Helen Gahagan Douglas, then a member of Congress representing California and running an ultimately unsuccessful campaign for Senate in 1950. Wiener Wyman was disappointed in Gahagan Douglas’s showing on the campaign trail and confronted her about it. Gahagan Douglas replied, “ ‘If you know so much about a campaign, here, here’s a card. Come see this lady and get into my campaign.’ ” Wiener Wyman took up the challenge and threw herself into this work, hanging posters and driving Gahagan Douglas to her campaign stops. Laughing, Wiener Wyman recalled, “I remember once changing my hose in the car with her in a parade. She took mine and I took hers. Crazy things a woman candidate worries about.”

Wiener Wyman began her own political career fresh out of college. In 1953, she ran a grassroots campaign for Los Angeles City Council that relied solely upon door-to-door conversations with her constituents, without the benefit of media coverage or traditional advertising. Her victory over established, male candidates was such a surprise that she recalls from the night of the election:

As the bulletins were handed to [Joe] Micchice, [a local radio announcer], he said, “I’m sure that the votes are on the wrong name.” So, he, during the night, would give my vote to Nash. Finally he put his hand over the mike–we have this on a record which is so wonderful–and he said, “Is this bulletin right?” Or, “Who the hell is Wiener?”

After a runoff election, Wiener Wyman came out on top. Of this dark horse winner, the Los Angeles Times declared, “It’s a girl!”

Wiener Wyman stood out as the youngest member and only woman on the Los Angeles City Council from 1953 to 1965. Notably, Wiener Wyman did not see herself as a victim of gender discrimination; rather, she saw her break with other council members in terms of age and experience. This, despite the fact that other city council members voted to not allow her personal leave to enjoy her honeymoon. Additionally, Wiener Wyman had to contend with the fact that “the only toilet was off the council chambers and that was for the men.” She recalled, “That became an incredible issue that got around town. Where was I going to go to the bathroom? I thought I would die over that!”

During her time in office, Wiener Wyman famously led the charge to entice the Brooklyn Dodgers to Los Angeles, making it the first Major League Baseball team west of the Mississippi River. Although the displacement of Mexican American families from Chavez Ravine and the building of Dodgers Stadium was controversial then and now, Wiener Wyman defended her support for this civic boosterism and the prestige it brought to Los Angeles. However, she conceded of her leadership on this fight: “it probably cost me some of my popularity.”

Beyond her twelve years in elected office, Wiener Wyman’s political legacy perhaps best lies in her fundraising efforts for other Democratic candidates. During one memorable event in the backyard of her Los Angeles home, Wiener Wyman and her husband, Eugene Wyman, hosted a dinner for Democratic congressional candidates and charged $5,000 a couple, an unthinkable sum in 1972.

Rosalind Wiener Wyman’s life and career point to the many ways in which California women have and continue to engage in political life, as well as the rich collection of political history at the Oral History Center. As we approach the hundredth anniversary of women’s suffrage, documenting the experiences of these women political leaders will become all the more important.

Amanda Tewes, Interviewer/Historian

From the Director: Oral History and the Berkeley Tradition

From the Director: Oral History and the Berkeley Tradition

On the evening of Thursday April 26th, the staff of the Oral History Center hosted our annual event in which we take the opportunity to express our gratitude to our remarkable narrators and our generous sponsors. I’ll also usually say a few words about the center and provide an overview of the scale of the work that we do for the benefit of those who might only know it just from the vantage point of being interviewed. Preparing my remarks was easy this year because 2018 happens to be a pretty special year at Berkeley: it marks the 150th anniversary of the founding of the university! What follows is an edited version of my remarks:

This evening I want to spend a few minutes sharing my thoughts on the essential role that this oral history program has played in this history of this university. See, the University of California was founded on March 23, 1868, just a little over 150 years ago. And while what we now know and love as the Oral History Center wasn’t established for another 90 years, in some very important ways, this program has been with the university since the beginning: it has been with the university through the first and second-hand experiences of those who built the university into what it is today, transmitted over the past 64 years through recordings now archived in the Bancroft Library.

Physicist Raymond Thayer Birge, from an interview completed in 1960, conveys his knowledge of the university’s earliest years from his departmental perch: “The Department of Physics is very old. It goes back to John Le Conte, the first man appointed to the faculty of the original University. He was appointed professor of physics, he was also acting president for those first two or three years. Then later on, I after we had had two or three presidents; he was president, I think for five years, Then he got fired, although that doesn’t appear on the public record, but he actually did. [But] he remained [on faculty] until I think 1891, when he died; and he was the first member of the original faculty to die, as well as being the first one to be appointed.”

The Faculty Club, designed by famed architect Bernard Maybeck, is a treasured institution on campus. In our 1962 interview with Leon Richardson, we get a first-hand account of its founding: “Well, I was one of the founders of the Faculty Club, and I can tell you just how it began. Three or four of us saw a little (tumbled down … unoccupied) cottage on the southern rim of the campus and we said among ourselves, ‘Couldn’t we rent one of those cottages, maybe for $5 a month and then hire a caterer to come and give a luncheon to us five days a week?’ Anyway, we hired the cottage and got the caterer and it went well. From that we began to expand and expanded until the day came when we got the regents to build us a clubhouse on the campus with Maybeck as the architect.” In another passage from the Richardson interview, we learn Jane Sather gave a considerable sum to pay for the bells of Sather Tower but when money was left over, the decision was made to build the structure that has welcomed visitors to campus since 1910, now called “Sather Gate.”

William Dennes, who arrived on campus as a junior professor of philosophy in 1915, many decades later recalls what he found: “The campus was mostly like a neglected ranch: foxtail and other dried grass in August, when the term then began, ragged and for the most part not gardened, [but there was] an ivy bed around California Hall. And Benjamin Ide Wheeler was very concerned that the boys and girls shouldn’t make paths across his ivy bed!”

Although the International House movement began in New York City, Berkeley established the second house in the country and our I-House remains a lively center of intercultural exchange today. In a 1969 oral history, Harry Edmonds offers his recollections: “One frosty morning in September, 1909, I was going up the steps of the Columbia Library … when I met a Chinese student coming down. I said, ‘Good morning. ‘ As I passed on, I noticed out of the corner of my eye that he had stopped. So I stopped and went back to him. He said, ‘Thank you for speaking to me. I’ve been in New York three weeks, and you are the first person who has spoken to me’ … I went on about my errand but had no sooner gotten around back of the library that I realized something extraordinary had happened. Here was a fellow, this student, who had come from the other side of the world, … he had been here for three weeks, and no one had spoken to him. What a tragedy. I retraced my steps to find him to see if I could be of some help, but he had vanished in the crowd. That evening when I went home, I told my wife of my experience. She asked if I couldn’t ‘do something about it.’” Before too long, Edmonds played an instrumental role in founding the International House movement.

I could go on quoting from interviews describing the rise of the Free Speech Movement and Ethnic Studies on campus, examinations of the Loyalty Oath and the creation of the several new campuses of the UC System, and, yes, there is a very good account of the founding of the Oral History Center, but I’ll stop here. These quotes were drawn from much longer oral histories which are just an exceedingly small sample of the 4000 interviews in our collection that document not only the history of this university but also the region, the state, and frankly, the world.

So what is to be gained from these interviews? Are they just colorful anecdotes or do they offer something greater?

If you get the chance to listen to the interviews, the cadence of the speech found in the oral histories is strikingly different today, as often is the vocabulary. We are in the process of digitizing these interviews, so in the years to come you’ll be able to listen to their words, how they spoke those words, and begin to explore how we might gain new understandings through voice and affect. These interviews also provide information not readily available in the public record, as hinted at in Birge’s recollection of John LeConte’s career challenges. Moreover, they offer detailed accounts of everyday life — the kinds of things that provide texture to our understanding of the past but might be ephemeral and thus exist only in our memories, otherwise disappearing when we do too and not documented in writing. They reveal the moments of inspiration behind the ideas, institutions, and innovations of the university; they reveal origins often shrouded in the mystery of epiphany and immediate experience. These interviews give experts the opportunity to share their ideas, discoveries, and challenges in everyday language, thus giving non-experts the opportunity to learn about complex and fascinating things outside of jargon-filled publications, for example. And, finally, they tell us just how Sather Gate came to be!

In 2018, 150 years since the University of California was established, I encourage you to dig into our collections and read the first person accounts of how and why Berkeley became one of the greatest universities in the world.

Martin Meeker, Charles B. Faulhaber Director of the Oral History Center

Checking in with Summer Institute Alum Marc Robinson

Checking-in with Summer Institute Alum Marc Robinson

When Marc Robinson traveled from Spokane, Washington to Berkeley, California in August 2017, it was in the name of narrative history. He came to the Advanced Oral History Summer Institute to work on his project about black student activism in the late 1960s, which was somewhere between dissertation and manuscript. He had done some interviews while earning a PhD in American Studies from Washington State University, but felt like he was just scratching the surface. Like many who understand the value of oral history in doing contemporary history, he wanted to talk to more people, get a broader range of narratives, and explore the way that some of the stories he was recording contradicted archival documents.

Robinson’s doctoral research was about student activism on campuses in the Northwest, particularly around those who were in the Black Student Union during a time of social and political unrest in the 1960s. He focused on two campuses, one urban — the University of Washington — and one rural — Washington State University. After doing several interviews with students who were active there, Robinson wanted to broaden his cohort of narrators to include not only black students, but their allies and the larger community of people connected to the Black Student Union, but were not students themselves.

He came to the Summer Institute looking for more training in longform life history interviews and left the program thinking deeply about what this type of interview can really provide to a researcher. “Narratives aren’t really telling the Truth, but their recollection of what happened as it pertains to them,” he says. He found that some of the narratives that he had collected challenged the materials he had found in the archives, which made him see interviewing as an opportunity to understand the complexity of memories. The program taught him to expect this complexity and see oral history as having transformative power. Another takeaway? The importance of the tech side of interviewing. “It made me think more about headphones, mics, the quality of sound, and knowing your equipment,” he says.

Since his time in Berkeley, Robinson was hired for a tenure track faculty job in the History Department at Cal State University San Bernardino (congratulations, Marc!), where he’ll start in the fall of 2018. He plans to continue working on his project and is interested in getting his students involved in the interviewing process. “It can be a really valuable teaching tool,” he says. He hopes to get his students involved in projects that illuminate local history, current events, and the community, something that Cal State San Bernardino has a track record of.

Please join us in congratulating Robinson on his new job! Look out for his book, which is on track to be out by 2020. We’re excited to see what he learns from his next round of interviews and what they can teach us about the times we are living in now.

Interested in learning more about Robinson? About the SI or joining us in 2018?

Follow him on Twitter @MarcARobinson1, and apply for the SI here.

Lester Telser: Beyond Conventions in Economics

Now online, An Oral History with Lester Telser: Beyond Conventions in Economics

Lester Telser is Professor of Economics Emeritus at the University of Chicago. A student at Chicago in the 1950s, Dr. Telser was first a professor in the Graduate School of Business until 1964. Dr. Telser’s life work is the theory of the core, a variant of game theory that involves coalitions of agents as opposed to individuals working to maximize their advantage. He used sophisticated mathematics to study why and how certain forms of markets are organized without appeals to more established concepts in economics. As both a student and colleague at the Chicago economics department, and as a fellow at both the Cowles Commission and the Cowles Foundation, Telser is a key witness to the transformation of the field of economics after World War II.

The impact of economics in our society is hard to overstate. Economics structures government policy, guides decision-making in firms both small and large, and indirectly shapes the larger political discourses in our society.

To enrich the understanding of the influence and sources of powerful economic ideas, the Becker Friedman Institute for Research in Economics at the University of Chicago set out in 2015 to capture oral histories of selected economists associated with Chicago economics. The aim was to preserve the experiences, views, and voices of influential economists and to document the historical origins of important economic ideas for the benefit of researchers, educators, and the broader public. This oral history with Lester Telser, conducted in ten sessions in Chicago, IL, from July to October 2017, is the third interview for the project.

Economist Life Stories is more than a collection of life histories; it chronicles the history of a scholarly community and institutions at the University of Chicago, such as the Graduate School of Business, the Cowles Commission, and the Department of Economics. It also reflects the achievements of faculty and students in the domains of economic policymaking and private enterprise around the world. Although this project focuses on the leaders and students of the University of Chicago Department of Economics, the Graduate School of Business, and the Law School, we hope to add more stories from economists around the world as the project expands.

Acknowledgments

Hodson Thornber and Paul Burnett organized the project with Toni Shears and Amy Boonstra of the Becker Friedman Institute, with important support from an advisory group of historians and economists.

Financial support for this work was provided by Hodson Thornber, a member of the Becker Friedman Institute Council, whose contribution is gratefully acknowledged.

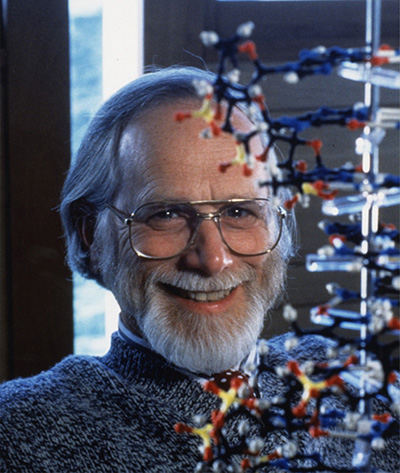

J. Michael Bishop: Scientist, UCSF Chancellor, and Nobel Laureate

This oral history with J. Michael Bishop is one in a series documenting bioscience and biotechnology in Northern California. Selecting Rous sarcoma virus, a cancer-causing retrovirus, after arriving at UCSF in 1968, Bishop was soon joined by Harold E. Varmus with whom he established a partnership legendary for its length and productivity. In a seminal publication of 1976, they established the proto-oncogene as a normal cell component and precursor of oncogenes. In 1989, Bishop and Varmus were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for this research. With some reluctance, Bishop agreed to become UCSF Chancellor in 1998. His highly productive eleven years saw the creation and staffing of the Mission Bay campus and record-breaking fundraising success, among other important events he oversaw. The oral history consists of five interviews conducted in 2016 and 2017, with an introduction by colleagues Bruce Alberts and Harold Varmus.