Author: Shanna Farrell

From the Archives: Staff Picks

This month, we’re bringing you a special edition of our From the Archives department. Below are interviews, all available in the OHC archives, recommended by each of us. Enjoy digging through the crates!

Martin Meeker’s pick:

Andre Tchelistcheff: Grapes, Wine, and Technology. Some lives in our collection of interviews are just profoundly interesting, and well worth digging into. This might be because of difficulties surmounted, achievements recognized, or simply the quality of the telling. Our 1979 oral history with Andre Tchelistcheff reveals one such life that ticks all of those boxes. From his birth in Russia in 1901, through his harrowing escape during the Revolution, to his years in France studying viticulture, and his decades quite literally remaking California’s wine industry, Tchelistcheff lived a remarkably influential life while remaining rooted in his passions throughout.

Roger Eardley-Pryor’s pick:

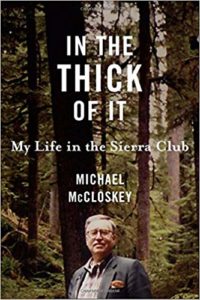

J. Michael McCloskey (Mike McCloskey), “Sierra Club Executive Director and Chairman, 1980s-1990s: A Perspective on Transitions in the Club and the Environmental Movement,” conducted in 1998 and published in 1999, is the second oral history with Mike McCloskey as part of the Sierra Club Oral History Project. Mike, a longtime leader in one of the largest environmental organizations in the United States, discusses the Club’s growing pains associated with an upsurge in membership amid Ronald Reagan’s anti-environmental actions in the early 1980s. Today, in lieu of modern assaults against environmental protections, Mike’s oral history sheds light on ways environmentalists managed those challenges and even expanded their purview to international issues.

Amanda Tewes pick:

Paul Burnett’s pick:

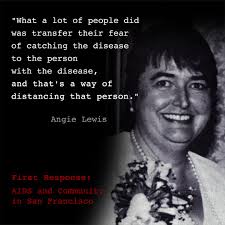

I choose nurse educator and clinical nurse Angie Lewis, who worked at UC San Francisco during the early years of the AIDS crisis. In Lewis’ interview, we really hear what it was like to first learn of this then-unknown disease that was killing gay people in San Francisco in the early 1980s. But we also hear touching stories of the mobilization of community and medical support for those who were suffering from AIDS.

David Dunham’s pick:

David Blackwell: African American Faculty and Senior Staff Oral History Project. Named after an esteemed mathematician and the first African-American tenured professor at Cal, David Blackwell Hall opened this fall to honor Professor Blackwell. Read more about his pioneering life in his oral history, part of our African American and Senior Faculty Oral History Project.

Todd Holmes’ pick:

I’d recommend Francis Mary Albrier: Determined Advocate for Racial Equality. This oral history captures the extraordinary life of one of Berkeley’s most prominent citizens, from her leading role in fighting discriminatory hiring in the City’s schools and businesses to desegregating the famed Richmond Shipyards. Moreover, through her oral history, you get a clear view of the many unsung citizens that organized communities of color to collectively push for change.

Shanna Farrell’s pick:

When I was first learning how to conduct longform interviews, I drew inspiration from Willa Baum, former director of the Oral History Center. She was an amazing interviewer, and her oral history interview provided insight into who she was, what drove her, and how she built the reputation of our office.

From the Director: October 2018

OHC Director Martin Meeker shares his work with the Oral History Association to update its core documents outlining best practices and ethical standards for the field. The committee, which Meeker is a part of, is seeking feedback through which is open for public comment through October 12, 2018.

![]()

Every decade or so, the Oral History Association (OHA) has convened a group of oral historians to examine, reconsider, and, often, redraft its core documents outlining best practices and ethical standards for the field. When Todd Moye assumed the presidency of OHA last fall, he announced that just such a project would be a key feature of his term. Soon a task force of fourteen members, including the excellent chairs Sarah Milligan and Troy Reeves, was established and a series of online meetings commenced. I was honored to be asked to serve on the task force and was very happy to work alongside so many accomplished scholars and dedicated oral historians.

Working fairly intensely for about nine months, the task force ultimately drafted six documents. Of those six, four are key. These include: Core Principles, Statement on Ethics, Best Practices, and what the committee is calling “For Participants in Oral History Interviews.” All of the documents are available for everyone to read online and the comment period remains open until October 12. Members of OHA will have the chance to give an up or down vote on the proposed new documents at the business meeting during upcoming OHA annual meeting on Saturday October 13.

As a member of the task force and as a deeply committed oral historian, I want to encourage everyone to engage with these documents both now and when, presumably, they are adopted. Unlike some previous iterations of these documents, the 2018 editions basically offer a full scale rethinking and rewrite of what came before. While there was much useful and insightful material in the previous versions and they served the organization well for years, many task force members thought that those documents both attempted to do “too much” and “too little.” I think that means that there were some pretty detailed prescriptions that were difficult to apply widely (“too much”) and yet much of what was written was a bit too vague and thus was difficult to implement in specific settings (“too little”). The current task force sought to remedy this, and we certainly hope that readers today agree.

The task force wrestled with a number of other questions that are either new or have become newly important over the past decade (the current version was adopted in October 2009). Not surprisingly, technology is at the top of the list. One way in which we attempted to deal with continuous technological innovation was to think about the universal questions and issues that the new innovations have summoned. In other words, we avoided getting into the weeds and writing specific instructions for the situation today because we know things will continue to evolve, and at a rapid rate. Although oral historians have long been aware of the potential challenges and needs that come with interviewing across lines of difference, there is certainly a greater sensitivity to “privilege” today, and the task force kept these concerns foremost when doing our work. But as with technology, we attempted to be open and not write the document so that it speaks only to one type of difference, privilege, or associated challenge, and instead provided guidelines and insight into the best way to handle sensitive relationships in a variety of situations.

When you read the documents, I encourage you to read first Sherna Berger Gluck’s “Introduction,” which provides a useful and tidy history of these documents over the decades, thus putting the newest versions in context. I think I can speak for my fellow task members in saying that we hope the work that we’ve done is received well and is seen as useful and valuable for, perhaps, the next 10 years.

Martin Meeker

Charles B. Faulhaber Director

Field Notes: More on Interviewing Around Trauma

by Shanna Farrell

@shanna_farrell

Trauma comes in many forms. So does the way we process this trauma, and the way we express it. For me, as an oral historian, this translates to how I conduct interviews and how I prepare for them. For the next couple of months, I’ll be reflecting on this for the OHC’s Field Notes section of our blog. I began this discussion in September, talking about a project that I’m working on with the Presidio Trust, a former U.S. Army base-turned National Park on the northern edge of San Francisco near the Golden Gate Bridge. We’re interviewing people who were involved in, or related to, the Presidio 27 mutiny that occured on October 14, 1968. Events in honor of the 50th anniversary will take place the weekend of October 13th and 14th at the Presidio.

Special care needs to be given to interviews that focus on trauma, as do the pre-interviews. The same rules do not apply for trauma-centric pre-interviews and the process must be flexible. Even just the idea of sitting down for an interview to recount these memories can be anxiety producing. It’s important for the interviewer to keep this in mind and be willing to adapt, or even abandon, their normal practices.

I was confronted with this recently for an upcoming interview. The narrator, who has been interviewed before for a book, agreed to participate in our project. During our first pre-interview, which I conducted with Presidio Historian, Barbara Berglund Sokolov, he expressed uncertainty about his memory and his ability to recall certain events. He was upfront about an illness that he lives with and the impact it has had on his life. He was specific about areas that he did not want discuss, which we noted and will respect.

He viewed this pre-interview, which lasted for about two hours, as the first of several. He requested that we put the interview outline together and mail it to him. Once he reviewed it, we would meet again to talk about the content. This is not normally how I operate. I usually have one meeting with a narrator wherein I schedule the interview. But, I needed to be flexible here, especially if I wanted to build rapport, create trust, and help cultivate a setting where he feels comfortable sharing his story. So we agreed to his request for multiple meetings before the actual interview.

Barbara and I put together interview outlines shortly after the first pre-interview meeting and mailed it off to the narrator. A couple of months passed until we met again. This time around, he seemed much more relaxed and comfortable. Though it was clear he hadn’t read the outline, we took no offense. We understood that he needed to read it in the company of others to discuss these memories and become more comfortable with doing the interview. This meeting lasted for another couple of hours, at the end of which he expressed his desire for more time. We agreed, because we wanted to ensure that he felt agency in the process.

Before the oral history interview, the three of us will have met at least three times. There will be more time spent doing pre-interviews than the actual interview. And this is okay. It may not be what I’m used to, but it feels right to allow the narrator his space to share his story on his terms. This is another form of shared authority, one of the many reasons that I feel so compelled by oral history. Our flexibility in the process will not only strengthen the interview, but hopefully it will allow the narrator the most support.

OHC Event with UCB J-School and Voice of Witness for “Six by Ten,” and a Q&A with author Mateo Hoke

Join us on 10/10 for an event with Voice of Witness at UC Berkeley’s Journalism School to celebrate the release of their newest book,

Six by Ten: Stories from Solitary.

The event, which will feature a conversation with editors Mateo Hoke and Taylor Pendergrass (and special guest!) moderated by the OHC’s Shanna Farrell.

We kick off at 6:30pm in the Logan Multimedia Center. There will be complimentary drinks and books for sale.

Editor (and J-School alum) Mateo Hoke took some time to speak with us about this project, his second with Voice of Witness. Hoke and Pendergrass began the project in 2014, which focuses on the experience of incarcerated people who were subjected to solitary confinement, and features twelve narrators. They interviewed some narrators over twenty times, and exchanged emails and letters with other for over two years.

Q: How did you get interested in oral history? When did you start to use it as a method in journalism?

My interest grew out of my reporting work. From early on I was interested in long interviews, and giving people the space to free associate and really tell their story in their own words, in their own way, with their own mannerisms and ways of speaking coming through. The first long interview work I did was in college.

On 9/11, after the towers fell, I went to a fire station and sat with the firefighters. We just sat and watched the news together, while I wrote down what they said. Honestly they didn’t say much. Everyone, including myself, was in shock and pretty quiet. But taking the time to sit with the firefighters, rather than just calling and asking for quotes, offered much more in terms of insight and emotion. It wasn’t oral history work, but it showed me early in my reporting career that spending time with people gave them the chance to settle in and talk more openly. Not long after that I started a reporting project with Cate Malek, who I later co-edited Palestine Speaks with, about the daily lives of undocumented Mexican immigrants living in Boulder. We were just a couple of undergrad j-school cubs but we put in the time and work to show up and really listen. We spent days with people, and would go back and back and back to follow up. The whole thing took eight months to research and write. We didn’t call what we were doing oral history work—it was very much journalistic—but it was planting the seeds for long-form interview based reporting. Later I started doing long-form literary interviews. I’d read an author’s entire body of work, then talk with them for hours about their writing, sometimes recording for the better part of a day. So from all of this interviewing grew an interest in oral history. Once I linked up with Voice of Witness in 2010 is when I really started to go into interviews thinking not just with my journalism training, but with oral history practices in mind too.

Q: How did you become interested in the prison system?

I’ve been friends with Taylor Pendergrass since 2003. And when you’re friends with Taylor, you’re going to hear perhaps more than you want to know about the dehumanization and racism that defines the US prison system. Even before he was out of law school he’d dedicated his life and his work to reshaping the so-called corrections system, so his influence played a role in me wanting to learn more from people first-hand about what goes in in our prisons and jails. Reading and music played a big roles as well. I’ve also spent a lot of time talking with people experiencing homelessness in both my personal and professional life, and the issue of homelessness is directly tied to prisons and punishment in the US, so I was coming at it from multiple routes and wanting to learn as much I could, not just about solitary confinement, but about the lives people lead before they enter the carceral system, then once they’re in the system, what they experience during months and years in isolation.

Q: Prisons can be tough to gain access to as a civilian. How were you able to gain access to the narrators in Six by Ten?

It’s important to note that prisons and jails are designed to be difficult to gain access to. Those in charge do not want stories from inside getting out, so they make it prohibitively difficult to do substantive interviews with people inside. I was able to visit two of our narrators in prison, in Michigan and California, but was not able to conduct quality interviews during these visits, so we wrote to each other, and conducted our ‘oral history’ interviews via writing, which brings up interesting conversations about oral history methodology when people cannot be interviewed in person. We also worked with a law clinic at Yale. The team there conducted powerful interviews with one of their clients who is incarcerated in Connecticut.

Q: How did you build rapport with your narrators? Were there any techniques that you used that were particularly successful in your interviews?

I’d like to think my technique is the same no matter who I’m interviewing. Listen. Be kind. Don’t judge. Open ears. Open heart. Open mind. And a bullshit meter that’s on high alert.

Q: What were some of the common themes that emerged from your interviews?

Two things. The first common theme that haunts me is the trauma that so many of our narrators experienced as kids. There have been studies done that link childhood trauma to incarceration in the US, but I didn’t really understand that relationship in three dimensions until I listened to narrator after narrator describe their childhoods to me in intimate detail. Hearing how so many grew up in abusive environments really brought home how our society fails kids long before they end up in prison. When kids grow up in abusive households, they learn that authority figures can’t be trusted. When young people of color are harassed, or threatened, or assaulted by police, they learn authority structures can’t be trusted. And when kids grow up in communities plagued by violence, they often learn that violence is an inherent way of life, rather than a choice that can perhaps be avoided. So when we fail to keep kids safe in their homes and in our communities, then lock them up in juvenile hall when they naturally repeat these cycles of violence, we’re just pumping generation after generation of young people into systems of aggression and incarceration. Trauma is passed down generationally. Don’t let anyone tell you different. At some point our society must decide to break the cycle, and heal these traumatic wounds, rather than blindly punish those who experience the effects of trauma.

The second common theme is simply the outright brutality of locking human beings in isolation. This book offer a raw and unflinching look at what happens to people when they’re pushed up to and beyond their breaking points. The amount of unnecessary suffering that is happening to people in these dark corners of American prisons and jails is haunting.

Q: This is your second book with Voice of Witness. How did Six by Ten differ from Palestine Speaks?

Six by Ten is a wholly American book. As I say in my introduction, this is a book about America. It’s a window into the soul and psyche of our culture. The process of interviewing and gathering narratives was obviously very different. Less trekking through the desert for this book. No trips to Gaza. But in a way it was more difficult to interview people here than in Palestine. Those who are locked up in the US are difficult to interview. And those who are out of prison do not have it easy. They are often caught in cycles of poverty, homelessness, and re-incarceration, while sometimes simultaneously managing mental illness and/or the traumatic effects of incarceration, including the effects of solitary. They’re struggling to survive in a culture that all but casts them aside. Jobs are especially scarce for the formerly incarcerated. Housing is difficult to obtain and expensive to maintain. Many people go into the system at a young age and come out institutionalized, broke, often unmedicated, and without the resources to get on their feet. If they don’t have family support, they can literally be struggling just to survive. Narrators would disappear, or be incarcerated, and we would spend immense amounts of time and energy to track them down. Each book was challenging in its own way, but this one in a uniquely American way.

Q: What do you hope the impact is of Six by Ten?

We hope that people read it and begin to comprehend the torture and dehumanization that’s happening everyday throughout the US in our prisons and jails, in our juvenile detention centers and immigration facilities. We hope that people realize how damaging this is for our communities when people return from incarceration worse off than when they went in, and then question what they can do to help fix this broken system. We hope they vote in their local elections for candidates that promote prison and sentencing reform, especially in local district attorney and judge races. I’d personally like Jeff Sessions to read it and sit down to an interview with me. I’d like to know he cares enough about this country to actually listen to those inside our prisons and jails, and is brave enough to have a conversation about what he thinks our society gains by continuing to allow the outright torture that’s happening everyday in isolation units throughout this country.

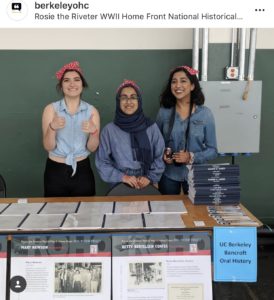

2018 Rosie Rally Home Front Festival: Preserving, Remembering, and Celebrating History

Hailie O’Bryan, OHC Student Worker

Hailie O’Bryan, one of the student workers at the OHC, attended the 2018 Rosie Rally Homefront Festival in Richmond, California in August. She tells us her first Rosie Rally, what she learned, and what we can learn.

Hi everybody!

My name is Hailie O’Bryan and I am a student worker at the Oral History Center. My recent experience at the Rosie Rally has undoubtedly been one of the biggest highlights during my time at the OHC.

When I first joined the OHC staff a little over a year ago, I was instantly introduced to the

Rosie the Riveter World War II Home Front Project that was being managed by David Dunham. While for I did very little work that was directly related to that project during my first several months, I heard the project mentioned several times a day. When I began to work on the OHC’s interviews, I was mesmerized by the significance of them, something that I had never truly considered before. These documents took stories straight from the mouths of living legends and immortalized them in the archive. Needless to say, when I was finally brought on the work on the Rosie the Riveter World War II Home Front Project, I was unimaginably excited. I would get to read, listen to, and watch someone give a first hand account of an era I had always held a deep fascination for.

I was not let down. The stories and accounts that I have been exposed to are unlike anything else I have ever experienced. These men and women have such an amazing energy about them that it almost flows from their oral histories. I began to do more work with the Rosie project, namely organizing and taking inventory of the database, syncing audio and video, and indexing and sequencing video interviews, exposing me to many different people with different stories.

When I was given the opportunity to represent the OHC at the 2018 Rosie Rally Home Front Festival in Richmond, CA, I was elated. I dressed up as Rosie the Riveter herself (or, my interpretation because I unfortunately do not own coveralls) and spend the day with my coworkers telling people about the wonderful interviews, including the unveiling of synced video interviews or the entire Rosie the Riveter World War II Home Front Project database which is going to be done by the end of this year.

At one point in the afternoon, the names of surviving Rosies were announced and they came onto a stage. I was awed by the fact that I was looking into the face of living, breathing history. My coworkers shared my sentiment because when I asked OHC student worker Gurshaant Bassi about her opinion of the rally, she said, “The rally brought history into being. It is essential to read the stories of the women who broke down the barriers we all benefit from now.” Aamna Haq, another one of my OHC co-workers, also shared this opinion. “It was a wonderful experience to learn about the importance of the Rosies in the World War II Era and the role they continue to play in the modern women’s empowerment,” she said.

Gurshaant and Haq are absolutely right. Given the progress of women’s rights since the 1940s, it is important to acknowledge and remember that women did not always have the same privilege as they do today. The Rosies laid the groundwork for woman’s role in the workforce. It is of tantamount importance that we remember the challenges they faced as they were doing this, especially as the years go on and we lose more of these amazing people.

I left the rally left feeling an enormous sense of gratitude towards the Rosies. After nearly 80 years, these women remain legends.To see them beyond the poster was an incredible experience for all of us.

Women still have much progress to be made, but by learning about the lives of these brave women we can remember that progress does not come easy. It is challenging but strikingly necessary. The Rosies chose to persevere amidst the pushback they experienced when they entered the workforce. We must do the same. In this way, the stories of the women involved in the Home Front Project are not of the fleeting past, but the stories of every woman having to prove their right to take space. In this way, we can recognize the stories of Rosies as our own. We are all Rosie.

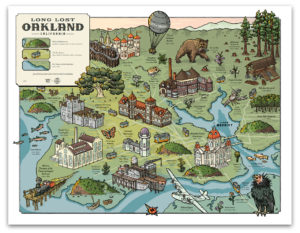

A Conversation with East Bay Yesterday Podcast Host, Liam O’Donoghue

Shanna Farrell, @shanna_farrell

Liam O’Donoghue is the host of the local history podcast, East Bay Yesterday. He tells the story of the region through baseball teams, earthquakes, grizzly bears, martial arts, activism, and music. We caught up with him recently to chat about how the show got its start, why history can help create empathy, and how he hopes to incorporate oral history. If you haven’t listened to the show yet, check it out on iTunes or head to his website.

Q: How did you get your start in podcasting?

My favorite aspect of journalism has always been interviewing people. I started my first ‘zine when I was 15 years old and published interviews with musicians from Chicago’s underground punk scene. Throughout my career as a print and online journalist, it always saddened me that 95 percent of most interviews never make it into the final article. I gravitated toward podcasting because the format allows interviews to really drive the narrative.

I started teaching myself basic digital recording and audio editing skills in spring of 2016 — mostly by watching tutorials on YouTube and reading “how to” articles on sites like Transom.org. I launched the first episode of East Bay Yesterday in September 2016 and have published nearly 40 episodes since then.

Q: What got you interested in East Bay history?

I started noticing a pattern: whenever I would talk to a longtime East Bay resident, they would always tell me incredible stories that I’d previously been completely unaware of. It made me realize the need to capture, share and celebrate these histories. Because of the rapid displacement of elders and people of color in the East Bay, I felt a huge urgency to devote myself to this project. The kinds of stories I want to collect are slipping away every day.

At the same time, there’s a big influx of newcomers to the East Bay, so I felt it would be useful to present local history in an accessible way. One of the effects of gentrification can be the erasure of previously existing cultures, so a goal of the podcast is to educate recently-arrived residents about what was here before they arrived.

A rather sad and ironic complaint I’ve often heard from longtime Oaklanders is that their new neighbors look at them like they — the Oakland “natives” — don’t belong. For example, I interviewed a Black man who had been using his front yard as a place to practice his martial arts for several decades. After white people started moving onto his block, somebody called the police on him and said he was “threatening.” My hope is that newcomers will have more empathy for longtime Oaklanders if they get to know them better, which is something the stories on my podcast strongly encourage.

Q: What are some of the reoccuring themes that you’re finding in your research?

The old cliche about “history repeating itself” is so true. There have been so many times that I’ve read old newspaper articles that feel like they could’ve been written yesterday. For example, the kind of language that’s being used to describe Oakland’s current boom is eerily similar to predictions about Oakland’s economic destiny in articles from the early 1900s or World War II or the first dot-com bubble, etc. Of course, most of these grandiose predictions fizzled out, which leads to some interesting conclusions when considering the outcome of this current cycle.

Another common theme is longtime residents’ apprehension about newcomers. The racial and socioeconomic dynamics vary, but any time there’s a large influx of people, the locals usually aren’t very thrilled. Some of this is attributable to racism, like when thousands of African Americans moved to Oakland seeking jobs during the World War II industrial boom. However, white “Okies” fleeing the Dust Bowl during the Great Depression were also vilified by many Oaklanders.

Q: How have you developed your podcast production process?

It’s an ongoing learning experience! I’m constantly trying to improve my craft by listening to shows like How Sound, a podcast about “radio storytelling,” reading books like Out on the Wire: Storytelling Secrets of the New Masters of Radio, and hanging out with other people in the Bay Area’s extremely friendly and supportive world of audio/radio producers. Getting to co-produce a story with the nationally-syndicated NPR program Snap Judgement was a big help because it finally allowed me to see “how the professionals do it.” It was my first time recording in a real studio instead of my bedroom.

Q: What kinds of archival material have you used?

My shows are usually built around original interviews, but I’m always really excited when I get to incorporate archival audio, because it adds a whole different vibe to the story— like the listener is really travelling back in time. Here are a few examples:

-In the episode about how living in Berkeley was one of the most transformative times in the life of Richard Pryor, I incorporated clips from his (short-lived) KPFA radio show and from his local standup comedy routines.

-In the episode about the Cypress Freeway collapse in West Oakland, I used audio from the California Highway Patrol’s radio communications describing the post-earthquake conditions, calling for emergency backup, etc.

-In an episode about the Oakland Community School, which was established and run by the Black Panther Party, I used a short clip from a 1977 TV documentary featuring this quote from Huey Newton: “They used to serve cookies at the primary school, but if you didn’t have money, you had to put your head on your desk until the other kids were done. I thought that was a problem. At the Oakland Community School, everybody eats.”

Q: Have you used any oral history interviews? How do you plan to incorporate oral history as you move forward?

There’s been surprisingly little coverage of Berkeley’s status as “America’s first sanctuary city.” For my research on that topic, I relied heavily on oral history interviews conducted by Eileen M. Purcell for the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley. Specifically her interviews with Rev. Gus Schultz and Bob Fitch, who were both pivotal figures in this movement are now deceased.

More recently, I used interviews conducted by Sue Mark, a local artist and historian (although she prefers the term “cultural researcher”), for an oral history project about Oakland’s Golden Gate neighborhood. She used these interviews to produce a short documentary a few years ago, but most of what she recorded had never been shared. I was honored and excited that she gave me her tape and transcripts to create an episode of East Bay Yesterday based on these interviews.

Moving forward, I’m extremely interested in incorporating interviews from the Oral History Center into future episodes of East Bay Yesterday. I’m a bit intimidated by the vast scope of your archives, but I’ve got a few ideas that I’m starting to explore…

Q: What’s your favorite thing about digging into East Bay history?

I love meeting people that I probably never would have met if I wasn’t making this podcast. For example, I was recently invited into the clubhouse of the East Bay Dragons, one of the world’s oldest Black motorcycle clubs. Getting the opportunity to sit down and have a long, emotional, enlightening conversation with a few of their members was an incredible experience.

Q: What are the top three episodes that you recommend for a new listener?

Besides the episodes I’ve already mentioned, these three are a few of my favorites:

- “The queen of the West Coast blues”: Sugar Pie DeSanto serves up sweet & spicy stories

- “This strange monument”: The story behind one of Oakland’s most prominent abandoned buildings

- Lenn Keller and the roots of the East Bay’s lesbian of color community

Q: What podcasts are you listening to?

- Scene on Radio

- The Bay (KQED’s daily news show)

- Longform

- Reveal

- 99% Invisible

- Wokeland

- Bay Curious

Notes from the Field

From the Summer Institute to the Presidio

Shanna Farrell, @shanna_farrell

Every year, as the sun burns bright over our quiet campus, we welcome a new cohort of Advanced Oral History Summer Institute participants, eager to spend a week immersed in all things oral history. August is an exciting time of year for us at the OHC. We get swept up in the enthusiasm of those who join us to learn; we love hearing people discuss their projects, make connections, and talk through issues they face.

The questions that the crowd ask throughout the week, each day building from the previous, are always thoughtful and make me think deeply about how to push my own work forward. These conversations take many forms and cover many topics. This year, there were many projects about events in the recent past, or that focus on issues that never seem to fade, like mass violence and marginalized communities. The questions that drive these projects are important to think about, research, record, archive, and preserve, and seep into the heart of my own interviews.

I found particular inspiration in the topics relating to trauma narratives because of a currently project that I’m working on with the Presidio Trust of San Francisco. For the past several months, I’ve been collaborating with their historian, Barbara Berglund Sokolov, on a series of interviews with people who have spent time at the Presidio in one capacity or another. Most recently, we have been focusing on the Presidio 27, a group of twenty-seven men—all of whom went AWOL during the Vietnam War and were incarcerated in the Ft. Scott stockade after being caught—who staged a mutiny on October 14, 1968 after one of their fellow inmates was fatally shot by an Army guard.

The project is ongoing, and we’re aiming to interview as many people as possible, including mutineers, guards, lawyers, media, protestors, and prisoners who arrived at the stockade in the wake of the mutinee. Many of the narrators who we’ve interviewed so far were traumatized by their involvement, and this requires careful consideration about best practices, and self-care. I’ve had to think through how best to support our narrators so as not to re-traumatize them, or Sokolov, or myself, in an environment that doesn’t feel threatening.

In preparation for these interviews, I spoke with the Director of the Presidio’s Veterans Program, who generously talked with me through the project and some red flags to be aware of, many of which he suggested that I could glean from the pre-interviews. Did the narrator mention a social or support network present in their lives? Did they seem responsive to the interview process? Were they overly emotional or withdrawn? Another issue was the interview setting. Several of the narrators had been imprisoned in tiny cement cells with no access to the outdoors for days at a time. Conducting the interviews in a basement conference room without windows was a bad idea, while holding them in open room with big windows facing the water pointing toward the North Bay was a better option. Transparency with our interview process, outline of questions, and final goals of the project felt more important here than other projects because the stakes felt higher. We also had to make sure that we asked questions that weren’t triggering and built in time for self-care after the interview.

While I was only just beginning this project when the Summer Institute kicked off last month, it gave me the opportunity to ponder the cornerstones of our work as oral historians, with a responsibility to our narrators, and ourselves. I heard our participants pose questions about their interviews involving trauma, and how they might approach this. I learned a lot from them, and feel lucky to have been privy to their thoughtfulness.

I’ll be writing more about this project–particularly about the interview arc and self-care, over the coming months, with new questions, considerations, and reflections. Stayed tuned.

ICYMI: From the Archives: Rosalind Wiener Wyman

From the Archives: Rosalind Wiener Wyman

Amanda Tewes, Interviewer/Historian

“They couldn’t believe that I could win,” Rosalind Wiener Wyman remembered about her unexpected election to the Los Angeles City Council in 1953. Over the course of several interviews in 1977 and 1978, Wiener Wyman shared her personal and political triumphs and losses, which culminated in her oral history, “It’s a Girl”: Three Terms on the Los Angeles City Council, 1953-1965; Three Decades in the Democratic Party, 1948-1978. Wiener Wyman’s memories as a woman politician at midcentury are part of the Oral History Center’s California Women Political Leaders Oral History Project, which documented “California women who became active in politics during the years between the passage of the women’s suffrage amendment and the…feminist movement.”

Wiener Wyman came by her passion for politics honestly. Speaking of her parents, she reflected, “I always felt their activities and interest in politics was steeped in me. In my baby book, at two, I’m looking up at a picture of FDR [Franklin Delano Roosevelt]. Most kids in their baby book are not looking at posters of FDR.”

While a student at the University of Southern California, Wiener Wyman and the campus Democratic Club worked on Harry Truman’s 1948 campaign. But her political work began in earnest when she met her “heroine,” Helen Gahagan Douglas, then a member of Congress representing California and running an ultimately unsuccessful campaign for Senate in 1950. Wiener Wyman was disappointed in Gahagan Douglas’s showing on the campaign trail and confronted her about it. Gahagan Douglas replied, “ ‘If you know so much about a campaign, here, here’s a card. Come see this lady and get into my campaign.’ ” Wiener Wyman took up the challenge and threw herself into this work, hanging posters and driving Gahagan Douglas to her campaign stops. Laughing, Wiener Wyman recalled, “I remember once changing my hose in the car with her in a parade. She took mine and I took hers. Crazy things a woman candidate worries about.”

Wiener Wyman began her own political career fresh out of college. In 1953, she ran a grassroots campaign for Los Angeles City Council that relied solely upon door-to-door conversations with her constituents, without the benefit of media coverage or traditional advertising. Her victory over established, male candidates was such a surprise that she recalls from the night of the election:

As the bulletins were handed to [Joe] Micchice, [a local radio announcer], he said, “I’m sure that the votes are on the wrong name.” So, he, during the night, would give my vote to Nash. Finally he put his hand over the mike – we have this on a record which is so wonderful – and he said, “Is this bulletin right?” Or, “Who the hell is Wiener?”

After a runoff election, Wiener Wyman came out on top. Of this dark horse winner, the Los Angeles Times declared, “It’s a girl!”

Wiener Wyman stood out as the youngest member and only woman on the Los Angeles City Council from 1953 to 1965. Notably, Wiener Wyman did not see herself as a victim of gender discrimination; rather, she saw her break with other council members in terms of age and experience. This, despite the fact that other city council members voted to not allow her personal leave to enjoy her honeymoon. Additionally, Wiener Wyman had to contend with the fact that “the only toilet was off the council chambers and that was for the men.” She recalled, “That became an incredible issue that got around town. Where was I going to go to the bathroom? I thought I would die over that!”

During her time in office, Wiener Wyman famously led the charge to entice the Brooklyn Dodgers to Los Angeles, making it the first Major League Baseball team west of the Mississippi River. Although the displacement of Mexican American families from Chavez Ravine and the building of Dodgers Stadium was controversial then and now, Wiener Wyman defended her support for this civic boosterism and the prestige it brought to Los Angeles. However, she conceded of her leadership on this fight: “it probably cost me some of my popularity.”

Beyond her twelve years in elected office, Wiener Wyman’s political legacy perhaps best lies in her fundraising efforts for other Democratic candidates. During one memorable event in the backyard of her Los Angeles home, Wiener Wyman and her husband, Eugene Wyman, hosted a dinner for Democratic congressional candidates. They charged $5,000 a couple, an unthinkable sum in 1972.

Rosalind Wiener Wyman’s life and career point to the many ways in which California women have and continue to engage in political life, as well as the rich collection of political history at the Oral History Center.

As we approach the hundredth anniversary of women’s suffrage, documenting the experiences of these women political leaders will become all the more important. Here at the Oral History Center, we hope to celebrate this anniversary by supporting an oral history project to document the contributions of women activists and politicians in the Bay Area. Recording the contributions of these impressive local women – political fundraisers, organizers, and elected officials – will help shape the national narrative about women’s historic, current, and future roles in American political life.For more information, please contact Amanda Tewes at atewes@berkeley.edu

OHC Director’s Column, September 2018

How Soon is Now?

Martin Meeker, @MartinDMeeker

Charles B. Faulhaber Director

Recently I was greeted with the unfortunate news that one of my narrators had passed away. My sadness was tempered by the fact that this man, Ed Howden, lived a very long life (he died just shy of 100 years) that was filled with many good accomplishments. He was a stalwart advocate of civil rights from his years heading up the Council for Civic Unity in 1940s and 50s San Francisco through his service as the first staff director of the California Fair Employment Practices Commission in the 1950s and 60s, and later, while working for the US Department of Justice.

There was plenty to talk about when I interviewed him in late 2016 and early 2017. But, by that time he was in his late 90s and many of the events we discussed had happened decades earlier. This experience got me thinking deeply about the “when” of oral history interviewing: when is the optimal time to interview someone? Is there a point when the time has passed?

First off, I feel it important to say I was honored to have the opportunity to interview Howden and, if you read his transcript, I’m sure you’ll agree that it is packed full of fascinating insights and first person accounts of transformative moments and trends in California. But there are also moments of forgetfulness and lack of precision, which was understandable. I had originally invited Howden for an interview in 2005, shortly after I arrived at Berkeley and having been awarded a small grant for a project about human rights commissions. Howden, as it turns out, was caring for his ailing wife at the time, so the interview was delayed by over 10 years. How would the interview have been different had I got to interview him then, or even years before? Howden was 97 when we began our recordings, and his was a valuable interview, I think.

Conversely, is an individual ever “too young” to be interviewed? I know of one project in which oral historians interviewed children, which must have been interesting! While I doubt the OHC will take on that demographic anytime soon, I have interviewed people substantially younger than me (I’m on the mature side of my 40s) and while a long (12+ hour) life history might better be done down the road, all of those interviews were interesting and strong on detail. What is potentially missing in terms of long range historical perspective is compensated for by quickness of recollection, ease with specifics, and strength in accuracy. Those interviews were shorter (typically 2 hours) and highly focused, but I think that they will prove exceedingly useful for scholars and others who are looking for more factual accounts on the topics at hand.

So, there may be no firm rule of thumb on the matter. If you are about to embark on a project in which you anticipate interviewing people of a certain age, it is a good idea to inform yourself of the potential limitations you could encounter on either end of the spectrum. If you plan on asking questions about events decades in the past, know that your narrator might remember little or misremember specifics: know that you’ll get a present perspective on past events, informed by decades of life experience. Also be aware of the potential for cognitive issues to crop up that, in extreme circumstances, might result in confusion, frustration, or other difficult moments for the narrator. Take care to recognize these signs and slow or end the interview if necessary. Memory is a fleeting thing.

We practice a pretty rigorous version of oral history at Berkeley, asking often probing questions and hitting back with follow-up questions that require additional reflective thought. This kind of intense interviewing might not be appropriate for some potential narrators because of health, age, or a combination thereof. On occasion, we turn down an oral history opportunity and instead recommend that the individual participate in a life-review interview: a type of interview best done by someone who knows the narrator well and gently guides that person through stories that they have told before. Oral historians, like other researchers who work with “human subjects,” are obliged to “do no harm” when going about their work.

Several interesting oral history projects have shown that our memories of events change, modulate, or even disappear not solely because of the wear and tear of time or illness but because we think anew about old events and we tend rewrite our own interpretations of things — if not the very facts period. Given how we create and recreate memory as we live, maybe the “when” question doesn’t matter too much? This is worth more thought, I bet.

Clearly there is a lot to think about and much more to be said on this matter. The best first step is to try to get to know your narrator a bit before beginning the interview to determine if that person would not only contribute to existing knowledge but would get something out of the oral history process too.

As always, we at the OHC are thinking and rethinking our methodology and welcome your thoughts and feedback.

The Talk Offstage: The Importance of Unrecorded Conversation in Oral History Interviewing

The Talk Offstage: The Importance of Unrecorded Conversation in Oral History Interviewing

by Paul Burnett

I pressed the red button at the top of my camera, which stopped the recording, with my eyes wide open, and sat back. The narrator stared into space and said, “I’ve never told that to anyone before.”

I’ll come back to this scene in a moment, but first I want to address the context that produced it. Here at the Oral History Center, we engage in a classic oral history best practice: an unrecorded, preliminary interview prior to an actual recording session. The reasons for doing so are fairly common-sense: to build a relationship of trust with the narrator, to review the narrator’s rights and the interviewer’s responsibilities, and to cover any technical aspects of the recording, such as signaling to mind the microphone or even to take a bathroom break. Beyond this list of basics, however, there is a whole world of communication between narrator and interviewer that surrounds the words that are ultimately recorded for posterity.

In my experience, narrators want to know who the interviewer is. It’s only fair. I’m asking them to narrate details about their personal and professional lives. Who is this person who is asking them all of these personal, probing questions? There is an imbalance there that can be mitigated if interviewers at least show they are willing to share details about themselves.

Oral historians are not therapists; there is no professional obligation not to share one’s own views, although there is a certain formality and distance that is appropriate during the performance of the interview. Outside of the interview context, however, we are perhaps more like producers or recording engineers for musicians. We are there to get the highest-resolution document of who narrators think they have been throughout their lives, what they have witnessed, and what they believe. To do that well, the interviewer needs to have a clear understanding of the context in which narrators have lived their lives, to imagine future audiences for what the narrators have to say, and to understand what the narrator wants to convey, and how they best hope to do so. For their part, narrators often want to know something, maybe a fair bit, about their interviewers: their backgrounds, their understanding of the history to be explored, and their goals for the project they are engaged in together.

But there is a deeper level of engagement with the narrator outside of the interview context, “offstage” as it were, that can sometimes lead to these revelatory moments on camera. If you can make it happen, there are few substitutes for breaking bread together. Even a snack on a break between sessions is an opportunity to share something about yourself, and it gives them a rest from talking on record, which is often quite tiring for most people. I always learn in these moments more about their passions or pastimes that might not be planned as part of the interview.

In one instance, a conversation about food over lunch ended up as the seed for an important discussion on camera about the relationship between diet, social policy, and governance. The more you know about the person you are interviewing, the more successful you’ll be in shaping the direction of the recorded discussion and the more rewardingly candid the conversations are likely to be. Careful planning of interviews is always important, but casual conversations can lead to fruitful and spontaneous explorations when it comes time to record.

To this day, it’s not exactly clear to me what led the narrator who I mentioned earlier to disclose this story with such candor. The story concerned a university-based scientist whose external support was withdrawn when the sponsor did not like the results of the research. We talked at length about the themes of the oral history project, and about the political dimensions of some of the work he was doing. But we also spent a lot of time talking about music, family, and personal challenges. I had not planned to go in the direction he suggested. In fact, the existing historical literature on the subject suggested that the story I expected would be very different form the one he ended up telling. It was a privilege to hear such important historical detail, which served to complicate our conventional understanding of a subject, and it had everything to do with the mutual trust between the narrator and the interviewer.

It’s important to stress that this talk offstage is not a calculation on my part. I don’t set out to cultivate a relationship with a narrator in order to get fuller disclosures than they would otherwise make. I owe it to my narrators to keep a formal tone in the interviews, to signal continually that, yes, they are being recorded. Professionally, your eyes should always be on helping narrators tell the richest stories they can about themselves and the world in which they’ve lived. The conversations offstage help narrators get comfortable with recorded communication beyond their own expectations of what they think an audience, however they define it, might want to hear. Of course, there isn’t always the luxury of time to build such a relationship with a narrator. But it is possible to develop rapport and learn helpful information in as little as five minutes. In fact, it’s in those constrained moments when I get peppered with the most rapid-fire personal questions. “We don’t have much time here, so who the heck are you?” By keeping in mind the boundaries the narrators have set for what they wish to discuss. And, by being open, vulnerable, and genuine, I can be a better partner in the process. It’s this trust that allows narrators to tell fuller stories when the red light is on and the recording device is rolling.

Scenes from an Interview