Join us on 10/10 for an event with Voice of Witness at UC Berkeley’s Journalism School to celebrate the release of their newest book,

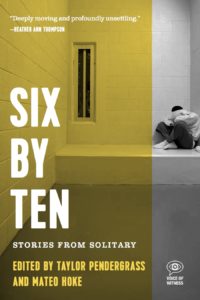

Six by Ten: Stories from Solitary.

The event, which will feature a conversation with editors Mateo Hoke and Taylor Pendergrass (and special guest!) moderated by the OHC’s Shanna Farrell.

We kick off at 6:30pm in the Logan Multimedia Center. There will be complimentary drinks and books for sale.

Editor (and J-School alum) Mateo Hoke took some time to speak with us about this project, his second with Voice of Witness. Hoke and Pendergrass began the project in 2014, which focuses on the experience of incarcerated people who were subjected to solitary confinement, and features twelve narrators. They interviewed some narrators over twenty times, and exchanged emails and letters with other for over two years.

Q: How did you get interested in oral history? When did you start to use it as a method in journalism?

My interest grew out of my reporting work. From early on I was interested in long interviews, and giving people the space to free associate and really tell their story in their own words, in their own way, with their own mannerisms and ways of speaking coming through. The first long interview work I did was in college.

On 9/11, after the towers fell, I went to a fire station and sat with the firefighters. We just sat and watched the news together, while I wrote down what they said. Honestly they didn’t say much. Everyone, including myself, was in shock and pretty quiet. But taking the time to sit with the firefighters, rather than just calling and asking for quotes, offered much more in terms of insight and emotion. It wasn’t oral history work, but it showed me early in my reporting career that spending time with people gave them the chance to settle in and talk more openly. Not long after that I started a reporting project with Cate Malek, who I later co-edited Palestine Speaks with, about the daily lives of undocumented Mexican immigrants living in Boulder. We were just a couple of undergrad j-school cubs but we put in the time and work to show up and really listen. We spent days with people, and would go back and back and back to follow up. The whole thing took eight months to research and write. We didn’t call what we were doing oral history work—it was very much journalistic—but it was planting the seeds for long-form interview based reporting. Later I started doing long-form literary interviews. I’d read an author’s entire body of work, then talk with them for hours about their writing, sometimes recording for the better part of a day. So from all of this interviewing grew an interest in oral history. Once I linked up with Voice of Witness in 2010 is when I really started to go into interviews thinking not just with my journalism training, but with oral history practices in mind too.

Q: How did you become interested in the prison system?

I’ve been friends with Taylor Pendergrass since 2003. And when you’re friends with Taylor, you’re going to hear perhaps more than you want to know about the dehumanization and racism that defines the US prison system. Even before he was out of law school he’d dedicated his life and his work to reshaping the so-called corrections system, so his influence played a role in me wanting to learn more from people first-hand about what goes in in our prisons and jails. Reading and music played a big roles as well. I’ve also spent a lot of time talking with people experiencing homelessness in both my personal and professional life, and the issue of homelessness is directly tied to prisons and punishment in the US, so I was coming at it from multiple routes and wanting to learn as much I could, not just about solitary confinement, but about the lives people lead before they enter the carceral system, then once they’re in the system, what they experience during months and years in isolation.

Q: Prisons can be tough to gain access to as a civilian. How were you able to gain access to the narrators in Six by Ten?

It’s important to note that prisons and jails are designed to be difficult to gain access to. Those in charge do not want stories from inside getting out, so they make it prohibitively difficult to do substantive interviews with people inside. I was able to visit two of our narrators in prison, in Michigan and California, but was not able to conduct quality interviews during these visits, so we wrote to each other, and conducted our ‘oral history’ interviews via writing, which brings up interesting conversations about oral history methodology when people cannot be interviewed in person. We also worked with a law clinic at Yale. The team there conducted powerful interviews with one of their clients who is incarcerated in Connecticut.

Q: How did you build rapport with your narrators? Were there any techniques that you used that were particularly successful in your interviews?

I’d like to think my technique is the same no matter who I’m interviewing. Listen. Be kind. Don’t judge. Open ears. Open heart. Open mind. And a bullshit meter that’s on high alert.

Q: What were some of the common themes that emerged from your interviews?

Two things. The first common theme that haunts me is the trauma that so many of our narrators experienced as kids. There have been studies done that link childhood trauma to incarceration in the US, but I didn’t really understand that relationship in three dimensions until I listened to narrator after narrator describe their childhoods to me in intimate detail. Hearing how so many grew up in abusive environments really brought home how our society fails kids long before they end up in prison. When kids grow up in abusive households, they learn that authority figures can’t be trusted. When young people of color are harassed, or threatened, or assaulted by police, they learn authority structures can’t be trusted. And when kids grow up in communities plagued by violence, they often learn that violence is an inherent way of life, rather than a choice that can perhaps be avoided. So when we fail to keep kids safe in their homes and in our communities, then lock them up in juvenile hall when they naturally repeat these cycles of violence, we’re just pumping generation after generation of young people into systems of aggression and incarceration. Trauma is passed down generationally. Don’t let anyone tell you different. At some point our society must decide to break the cycle, and heal these traumatic wounds, rather than blindly punish those who experience the effects of trauma.

The second common theme is simply the outright brutality of locking human beings in isolation. This book offer a raw and unflinching look at what happens to people when they’re pushed up to and beyond their breaking points. The amount of unnecessary suffering that is happening to people in these dark corners of American prisons and jails is haunting.

Q: This is your second book with Voice of Witness. How did Six by Ten differ from Palestine Speaks?

Six by Ten is a wholly American book. As I say in my introduction, this is a book about America. It’s a window into the soul and psyche of our culture. The process of interviewing and gathering narratives was obviously very different. Less trekking through the desert for this book. No trips to Gaza. But in a way it was more difficult to interview people here than in Palestine. Those who are locked up in the US are difficult to interview. And those who are out of prison do not have it easy. They are often caught in cycles of poverty, homelessness, and re-incarceration, while sometimes simultaneously managing mental illness and/or the traumatic effects of incarceration, including the effects of solitary. They’re struggling to survive in a culture that all but casts them aside. Jobs are especially scarce for the formerly incarcerated. Housing is difficult to obtain and expensive to maintain. Many people go into the system at a young age and come out institutionalized, broke, often unmedicated, and without the resources to get on their feet. If they don’t have family support, they can literally be struggling just to survive. Narrators would disappear, or be incarcerated, and we would spend immense amounts of time and energy to track them down. Each book was challenging in its own way, but this one in a uniquely American way.

Q: What do you hope the impact is of Six by Ten?

We hope that people read it and begin to comprehend the torture and dehumanization that’s happening everyday throughout the US in our prisons and jails, in our juvenile detention centers and immigration facilities. We hope that people realize how damaging this is for our communities when people return from incarceration worse off than when they went in, and then question what they can do to help fix this broken system. We hope they vote in their local elections for candidates that promote prison and sentencing reform, especially in local district attorney and judge races. I’d personally like Jeff Sessions to read it and sit down to an interview with me. I’d like to know he cares enough about this country to actually listen to those inside our prisons and jails, and is brave enough to have a conversation about what he thinks our society gains by continuing to allow the outright torture that’s happening everyday in isolation units throughout this country.