Tag: september 2018

2018 Rosie Rally Home Front Festival: Preserving, Remembering, and Celebrating History

Hailie O’Bryan, OHC Student Worker

Hailie O’Bryan, one of the student workers at the OHC, attended the 2018 Rosie Rally Homefront Festival in Richmond, California in August. She tells us her first Rosie Rally, what she learned, and what we can learn.

Hi everybody!

My name is Hailie O’Bryan and I am a student worker at the Oral History Center. My recent experience at the Rosie Rally has undoubtedly been one of the biggest highlights during my time at the OHC.

When I first joined the OHC staff a little over a year ago, I was instantly introduced to the

Rosie the Riveter World War II Home Front Project that was being managed by David Dunham. While for I did very little work that was directly related to that project during my first several months, I heard the project mentioned several times a day. When I began to work on the OHC’s interviews, I was mesmerized by the significance of them, something that I had never truly considered before. These documents took stories straight from the mouths of living legends and immortalized them in the archive. Needless to say, when I was finally brought on the work on the Rosie the Riveter World War II Home Front Project, I was unimaginably excited. I would get to read, listen to, and watch someone give a first hand account of an era I had always held a deep fascination for.

I was not let down. The stories and accounts that I have been exposed to are unlike anything else I have ever experienced. These men and women have such an amazing energy about them that it almost flows from their oral histories. I began to do more work with the Rosie project, namely organizing and taking inventory of the database, syncing audio and video, and indexing and sequencing video interviews, exposing me to many different people with different stories.

When I was given the opportunity to represent the OHC at the 2018 Rosie Rally Home Front Festival in Richmond, CA, I was elated. I dressed up as Rosie the Riveter herself (or, my interpretation because I unfortunately do not own coveralls) and spend the day with my coworkers telling people about the wonderful interviews, including the unveiling of synced video interviews or the entire Rosie the Riveter World War II Home Front Project database which is going to be done by the end of this year.

At one point in the afternoon, the names of surviving Rosies were announced and they came onto a stage. I was awed by the fact that I was looking into the face of living, breathing history. My coworkers shared my sentiment because when I asked OHC student worker Gurshaant Bassi about her opinion of the rally, she said, “The rally brought history into being. It is essential to read the stories of the women who broke down the barriers we all benefit from now.” Aamna Haq, another one of my OHC co-workers, also shared this opinion. “It was a wonderful experience to learn about the importance of the Rosies in the World War II Era and the role they continue to play in the modern women’s empowerment,” she said.

Gurshaant and Haq are absolutely right. Given the progress of women’s rights since the 1940s, it is important to acknowledge and remember that women did not always have the same privilege as they do today. The Rosies laid the groundwork for woman’s role in the workforce. It is of tantamount importance that we remember the challenges they faced as they were doing this, especially as the years go on and we lose more of these amazing people.

I left the rally left feeling an enormous sense of gratitude towards the Rosies. After nearly 80 years, these women remain legends.To see them beyond the poster was an incredible experience for all of us.

Women still have much progress to be made, but by learning about the lives of these brave women we can remember that progress does not come easy. It is challenging but strikingly necessary. The Rosies chose to persevere amidst the pushback they experienced when they entered the workforce. We must do the same. In this way, the stories of the women involved in the Home Front Project are not of the fleeting past, but the stories of every woman having to prove their right to take space. In this way, we can recognize the stories of Rosies as our own. We are all Rosie.

A Conversation with East Bay Yesterday Podcast Host, Liam O’Donoghue

Shanna Farrell, @shanna_farrell

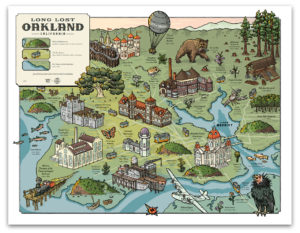

Liam O’Donoghue is the host of the local history podcast, East Bay Yesterday. He tells the story of the region through baseball teams, earthquakes, grizzly bears, martial arts, activism, and music. We caught up with him recently to chat about how the show got its start, why history can help create empathy, and how he hopes to incorporate oral history. If you haven’t listened to the show yet, check it out on iTunes or head to his website.

Q: How did you get your start in podcasting?

My favorite aspect of journalism has always been interviewing people. I started my first ‘zine when I was 15 years old and published interviews with musicians from Chicago’s underground punk scene. Throughout my career as a print and online journalist, it always saddened me that 95 percent of most interviews never make it into the final article. I gravitated toward podcasting because the format allows interviews to really drive the narrative.

I started teaching myself basic digital recording and audio editing skills in spring of 2016 — mostly by watching tutorials on YouTube and reading “how to” articles on sites like Transom.org. I launched the first episode of East Bay Yesterday in September 2016 and have published nearly 40 episodes since then.

Q: What got you interested in East Bay history?

I started noticing a pattern: whenever I would talk to a longtime East Bay resident, they would always tell me incredible stories that I’d previously been completely unaware of. It made me realize the need to capture, share and celebrate these histories. Because of the rapid displacement of elders and people of color in the East Bay, I felt a huge urgency to devote myself to this project. The kinds of stories I want to collect are slipping away every day.

At the same time, there’s a big influx of newcomers to the East Bay, so I felt it would be useful to present local history in an accessible way. One of the effects of gentrification can be the erasure of previously existing cultures, so a goal of the podcast is to educate recently-arrived residents about what was here before they arrived.

A rather sad and ironic complaint I’ve often heard from longtime Oaklanders is that their new neighbors look at them like they — the Oakland “natives” — don’t belong. For example, I interviewed a Black man who had been using his front yard as a place to practice his martial arts for several decades. After white people started moving onto his block, somebody called the police on him and said he was “threatening.” My hope is that newcomers will have more empathy for longtime Oaklanders if they get to know them better, which is something the stories on my podcast strongly encourage.

Q: What are some of the reoccuring themes that you’re finding in your research?

The old cliche about “history repeating itself” is so true. There have been so many times that I’ve read old newspaper articles that feel like they could’ve been written yesterday. For example, the kind of language that’s being used to describe Oakland’s current boom is eerily similar to predictions about Oakland’s economic destiny in articles from the early 1900s or World War II or the first dot-com bubble, etc. Of course, most of these grandiose predictions fizzled out, which leads to some interesting conclusions when considering the outcome of this current cycle.

Another common theme is longtime residents’ apprehension about newcomers. The racial and socioeconomic dynamics vary, but any time there’s a large influx of people, the locals usually aren’t very thrilled. Some of this is attributable to racism, like when thousands of African Americans moved to Oakland seeking jobs during the World War II industrial boom. However, white “Okies” fleeing the Dust Bowl during the Great Depression were also vilified by many Oaklanders.

Q: How have you developed your podcast production process?

It’s an ongoing learning experience! I’m constantly trying to improve my craft by listening to shows like How Sound, a podcast about “radio storytelling,” reading books like Out on the Wire: Storytelling Secrets of the New Masters of Radio, and hanging out with other people in the Bay Area’s extremely friendly and supportive world of audio/radio producers. Getting to co-produce a story with the nationally-syndicated NPR program Snap Judgement was a big help because it finally allowed me to see “how the professionals do it.” It was my first time recording in a real studio instead of my bedroom.

Q: What kinds of archival material have you used?

My shows are usually built around original interviews, but I’m always really excited when I get to incorporate archival audio, because it adds a whole different vibe to the story— like the listener is really travelling back in time. Here are a few examples:

-In the episode about how living in Berkeley was one of the most transformative times in the life of Richard Pryor, I incorporated clips from his (short-lived) KPFA radio show and from his local standup comedy routines.

-In the episode about the Cypress Freeway collapse in West Oakland, I used audio from the California Highway Patrol’s radio communications describing the post-earthquake conditions, calling for emergency backup, etc.

-In an episode about the Oakland Community School, which was established and run by the Black Panther Party, I used a short clip from a 1977 TV documentary featuring this quote from Huey Newton: “They used to serve cookies at the primary school, but if you didn’t have money, you had to put your head on your desk until the other kids were done. I thought that was a problem. At the Oakland Community School, everybody eats.”

Q: Have you used any oral history interviews? How do you plan to incorporate oral history as you move forward?

There’s been surprisingly little coverage of Berkeley’s status as “America’s first sanctuary city.” For my research on that topic, I relied heavily on oral history interviews conducted by Eileen M. Purcell for the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley. Specifically her interviews with Rev. Gus Schultz and Bob Fitch, who were both pivotal figures in this movement are now deceased.

More recently, I used interviews conducted by Sue Mark, a local artist and historian (although she prefers the term “cultural researcher”), for an oral history project about Oakland’s Golden Gate neighborhood. She used these interviews to produce a short documentary a few years ago, but most of what she recorded had never been shared. I was honored and excited that she gave me her tape and transcripts to create an episode of East Bay Yesterday based on these interviews.

Moving forward, I’m extremely interested in incorporating interviews from the Oral History Center into future episodes of East Bay Yesterday. I’m a bit intimidated by the vast scope of your archives, but I’ve got a few ideas that I’m starting to explore…

Q: What’s your favorite thing about digging into East Bay history?

I love meeting people that I probably never would have met if I wasn’t making this podcast. For example, I was recently invited into the clubhouse of the East Bay Dragons, one of the world’s oldest Black motorcycle clubs. Getting the opportunity to sit down and have a long, emotional, enlightening conversation with a few of their members was an incredible experience.

Q: What are the top three episodes that you recommend for a new listener?

Besides the episodes I’ve already mentioned, these three are a few of my favorites:

- “The queen of the West Coast blues”: Sugar Pie DeSanto serves up sweet & spicy stories

- “This strange monument”: The story behind one of Oakland’s most prominent abandoned buildings

- Lenn Keller and the roots of the East Bay’s lesbian of color community

Q: What podcasts are you listening to?

- Scene on Radio

- The Bay (KQED’s daily news show)

- Longform

- Reveal

- 99% Invisible

- Wokeland

- Bay Curious

Notes from the Field

From the Summer Institute to the Presidio

Shanna Farrell, @shanna_farrell

Every year, as the sun burns bright over our quiet campus, we welcome a new cohort of Advanced Oral History Summer Institute participants, eager to spend a week immersed in all things oral history. August is an exciting time of year for us at the OHC. We get swept up in the enthusiasm of those who join us to learn; we love hearing people discuss their projects, make connections, and talk through issues they face.

The questions that the crowd ask throughout the week, each day building from the previous, are always thoughtful and make me think deeply about how to push my own work forward. These conversations take many forms and cover many topics. This year, there were many projects about events in the recent past, or that focus on issues that never seem to fade, like mass violence and marginalized communities. The questions that drive these projects are important to think about, research, record, archive, and preserve, and seep into the heart of my own interviews.

I found particular inspiration in the topics relating to trauma narratives because of a currently project that I’m working on with the Presidio Trust of San Francisco. For the past several months, I’ve been collaborating with their historian, Barbara Berglund Sokolov, on a series of interviews with people who have spent time at the Presidio in one capacity or another. Most recently, we have been focusing on the Presidio 27, a group of twenty-seven men—all of whom went AWOL during the Vietnam War and were incarcerated in the Ft. Scott stockade after being caught—who staged a mutiny on October 14, 1968 after one of their fellow inmates was fatally shot by an Army guard.

The project is ongoing, and we’re aiming to interview as many people as possible, including mutineers, guards, lawyers, media, protestors, and prisoners who arrived at the stockade in the wake of the mutinee. Many of the narrators who we’ve interviewed so far were traumatized by their involvement, and this requires careful consideration about best practices, and self-care. I’ve had to think through how best to support our narrators so as not to re-traumatize them, or Sokolov, or myself, in an environment that doesn’t feel threatening.

In preparation for these interviews, I spoke with the Director of the Presidio’s Veterans Program, who generously talked with me through the project and some red flags to be aware of, many of which he suggested that I could glean from the pre-interviews. Did the narrator mention a social or support network present in their lives? Did they seem responsive to the interview process? Were they overly emotional or withdrawn? Another issue was the interview setting. Several of the narrators had been imprisoned in tiny cement cells with no access to the outdoors for days at a time. Conducting the interviews in a basement conference room without windows was a bad idea, while holding them in open room with big windows facing the water pointing toward the North Bay was a better option. Transparency with our interview process, outline of questions, and final goals of the project felt more important here than other projects because the stakes felt higher. We also had to make sure that we asked questions that weren’t triggering and built in time for self-care after the interview.

While I was only just beginning this project when the Summer Institute kicked off last month, it gave me the opportunity to ponder the cornerstones of our work as oral historians, with a responsibility to our narrators, and ourselves. I heard our participants pose questions about their interviews involving trauma, and how they might approach this. I learned a lot from them, and feel lucky to have been privy to their thoughtfulness.

I’ll be writing more about this project–particularly about the interview arc and self-care, over the coming months, with new questions, considerations, and reflections. Stayed tuned.

ICYMI: From the Archives: Rosalind Wiener Wyman

From the Archives: Rosalind Wiener Wyman

Amanda Tewes, Interviewer/Historian

“They couldn’t believe that I could win,” Rosalind Wiener Wyman remembered about her unexpected election to the Los Angeles City Council in 1953. Over the course of several interviews in 1977 and 1978, Wiener Wyman shared her personal and political triumphs and losses, which culminated in her oral history, “It’s a Girl”: Three Terms on the Los Angeles City Council, 1953-1965; Three Decades in the Democratic Party, 1948-1978. Wiener Wyman’s memories as a woman politician at midcentury are part of the Oral History Center’s California Women Political Leaders Oral History Project, which documented “California women who became active in politics during the years between the passage of the women’s suffrage amendment and the…feminist movement.”

Wiener Wyman came by her passion for politics honestly. Speaking of her parents, she reflected, “I always felt their activities and interest in politics was steeped in me. In my baby book, at two, I’m looking up at a picture of FDR [Franklin Delano Roosevelt]. Most kids in their baby book are not looking at posters of FDR.”

While a student at the University of Southern California, Wiener Wyman and the campus Democratic Club worked on Harry Truman’s 1948 campaign. But her political work began in earnest when she met her “heroine,” Helen Gahagan Douglas, then a member of Congress representing California and running an ultimately unsuccessful campaign for Senate in 1950. Wiener Wyman was disappointed in Gahagan Douglas’s showing on the campaign trail and confronted her about it. Gahagan Douglas replied, “ ‘If you know so much about a campaign, here, here’s a card. Come see this lady and get into my campaign.’ ” Wiener Wyman took up the challenge and threw herself into this work, hanging posters and driving Gahagan Douglas to her campaign stops. Laughing, Wiener Wyman recalled, “I remember once changing my hose in the car with her in a parade. She took mine and I took hers. Crazy things a woman candidate worries about.”

Wiener Wyman began her own political career fresh out of college. In 1953, she ran a grassroots campaign for Los Angeles City Council that relied solely upon door-to-door conversations with her constituents, without the benefit of media coverage or traditional advertising. Her victory over established, male candidates was such a surprise that she recalls from the night of the election:

As the bulletins were handed to [Joe] Micchice, [a local radio announcer], he said, “I’m sure that the votes are on the wrong name.” So, he, during the night, would give my vote to Nash. Finally he put his hand over the mike – we have this on a record which is so wonderful – and he said, “Is this bulletin right?” Or, “Who the hell is Wiener?”

After a runoff election, Wiener Wyman came out on top. Of this dark horse winner, the Los Angeles Times declared, “It’s a girl!”

Wiener Wyman stood out as the youngest member and only woman on the Los Angeles City Council from 1953 to 1965. Notably, Wiener Wyman did not see herself as a victim of gender discrimination; rather, she saw her break with other council members in terms of age and experience. This, despite the fact that other city council members voted to not allow her personal leave to enjoy her honeymoon. Additionally, Wiener Wyman had to contend with the fact that “the only toilet was off the council chambers and that was for the men.” She recalled, “That became an incredible issue that got around town. Where was I going to go to the bathroom? I thought I would die over that!”

During her time in office, Wiener Wyman famously led the charge to entice the Brooklyn Dodgers to Los Angeles, making it the first Major League Baseball team west of the Mississippi River. Although the displacement of Mexican American families from Chavez Ravine and the building of Dodgers Stadium was controversial then and now, Wiener Wyman defended her support for this civic boosterism and the prestige it brought to Los Angeles. However, she conceded of her leadership on this fight: “it probably cost me some of my popularity.”

Beyond her twelve years in elected office, Wiener Wyman’s political legacy perhaps best lies in her fundraising efforts for other Democratic candidates. During one memorable event in the backyard of her Los Angeles home, Wiener Wyman and her husband, Eugene Wyman, hosted a dinner for Democratic congressional candidates. They charged $5,000 a couple, an unthinkable sum in 1972.

Rosalind Wiener Wyman’s life and career point to the many ways in which California women have and continue to engage in political life, as well as the rich collection of political history at the Oral History Center.

As we approach the hundredth anniversary of women’s suffrage, documenting the experiences of these women political leaders will become all the more important. Here at the Oral History Center, we hope to celebrate this anniversary by supporting an oral history project to document the contributions of women activists and politicians in the Bay Area. Recording the contributions of these impressive local women – political fundraisers, organizers, and elected officials – will help shape the national narrative about women’s historic, current, and future roles in American political life.For more information, please contact Amanda Tewes at atewes@berkeley.edu