Author: Shanna Farrell

Paul A. Bissinger, Jr.: Lifelong San Franciscan and Patron of the Arts

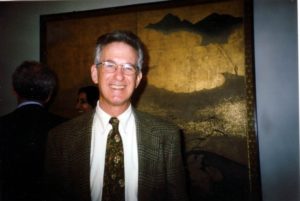

We are pleased to announce the release of our interview with Paul A. Bissinger, Jr. Bissinger was born in San Francisco, California in 1934 to Paul Bissinger and Marjorie Pearl Walter-Bissinger. He was raised on Divisidero Street and attended the Town School. He attended high school at the Phillips Exeter Academy, attended college at Stanford University, and earned a graduate degree from the American Institute for Foreign Trade. He served in the Navy in the 1950s, which took him to Japan, Hong Kong, and Manila. He’s been a life-long patron of the arts, which began as a child. He has a passion for the San Francisco Youth Orchestra, which he has been involved with for many years, and his service was honored by a performance dedicated to him on his 70th birthday.

In his interview, Bissinger discusses his early life, education, time in the Navy, meeting his wife, Kathy, and starting a family, working for his family business, and commitment to the local arts community. He also talks about serving on multiple boards for arts organizations, including for the San Francisco Youth Orchestra and Asian Art Museum.

OHC Announces Summer Fellowship for UC Graduate Student of Color

UC Berkeley’s Oral History Center is offering a $2,000 summer fellowship to a graduate student of color enrolled in the UC system. Aimed at early to mid-career oral historians, this fellowship provides an opportunity to conduct a longform life history interview with a leading figure in the arts or humanities. The selected fellow will conduct a 4-8 hour interview on video, which will be archived at The Bancroft Library. The fellow will see the interview series through from conception to completion and will present on their project at the Oral History Center’s annual Summer Institute.

This fellowship is open to graduate students of color who are enrolled in the UC system. Preference will be given to projects with a U.S. focus, but consideration will be given to international projects that have impact in the U.S.

The fellow will work with OHC Interviewer Shanna Farrell to hone project planning, the structure of the interview, and presentation. Interviewing will take place during June, July, and August. The fellow is expected to be on UC Berkeley’s campus during the Summer Institute, which takes place from August 5-9, 2019. The fellow will have the opportunity to work out of the Doe Library and check books out as needed. Equipment (if needed) and transcription for the interviews will be provided by the Oral History Center.

Applications are open January 14 – February 25, 2019. Award notifications will be send out in late March. Please email Shanna Farrell at sfarrell@library.berkeley.edu with any questions.

OHC Director’s Column: December 2018

The Year in Review

by Martin Meeker

It is no exaggeration to write that 2018 is one for the record books as far as the Oral History Center is concerned. I can write with great pride that this year the Center conducted more hours of interviews than at any other time in our 64 year history. And, while not as easy to quantify, I have listened to and read through enough of our interviews (along with conducting a few myself) to report that they are as illuminating, interesting, and important as any we’ve yet done. As I approached writing this final newsletter column of 2018, it wasn’t the grasping for a story that made me miss my deadline, rather I was stuck on just which stories to tell — and when to find time to do it!

We are thrilled with the opportunities that come with the challenge of working so hard. If you read this column regularly, you’ll know that the Oral History Center is a “soft money” operation of the university, meaning that we need to raise funds to conduct our oral histories and make them available to you. So, all of this work means that foundations, organizations, and individuals like you have invested in this work and given us the honor of conducting these remarkable interviews. We are thrilled that, thanks to you, we are so busy — and, at year’s end, we invite you to help us continue this good work in 2019 by supporting us now with a donation.

Surely none of this could happen without one essential ingredient: a remarkable, smart, and hard-working group of colleagues. I could easily write a column on each of my colleagues’ contributions over the past year, which have been nothing short of heroic, so I’ll struggle here with this limited space: Amanda Tewes and Roger Eardley-Pryor each joined us in the spring as historian/interviewers and, in just a matter of months, both have proved themselves essential by conducting excellent interviews and contributing in valuable ways to the life of the office. Todd Holmes, who has been with us since 2016, is a serious scholar and a project development mastermind, serving as the driving force behind several exciting new initiatives. Shanna Farrell, historian and longtime head of our educational initiatives, conducted a remarkable number of individual interviews this year and also took over editing responsibilities for this now-monthly newsletter. Paul Burnett, with us now for five years, eagerly takes on some of the most intellectually challenging and complex oral histories and always excels. And, last but not least, David Dunham, our tech guru, quite literally worked two jobs in 2018: as technical lead and production manager he ensured that everything happened as it must — oh, and he also managed the project that brought you the amazing new search engine launched last month. I must also not forget to pay tribute to our group of student employees — 13 this semester — who do an expanding amount of work and perform an increasingly complex set of duties. Thank you!

So what has this inveterate and skilled, yet innovative and scrappy band of oral historians accomplished over the past year? Here are some of our highlights:

- We continued our partnership with the Getty Trust, conducting a number of interviews with Getty curators and trustees and with influential artists, including a group Latino artists. We’ve already begun a project on African-American artists, which will be a major feature of our 2019 agenda;

- We conducted several interviews for our Chicano Studies oral history project which will culminate in a full-length documentary film produced over the coming years;

- We maintained our commitment to documenting the history of the University of California with a small but fascinating project on the campus political organization SLATE and individual interviews with several faculty leaders, including Berkeley Law Dean Jesse Choper, UC President Mark Yudof, Berkeley provost Paul Gray, and Nobel laureate and UCSF chancellor J. Michael Bishop;

- We resurrected our long-running series on the history of wine in California with two new projects, one capturing the story of Harlan Estate and the other marking the 75th anniversary of Napa Valley Vintners;

- We completed large groups of interviews documenting life in and around the East Bay Regional Park District and the San Francisco Presidio;

- We continued our tradition of interviewing those who have made important contributions and lived memorable lives, including famed herbalist and clothing designer Jeanne Rose, philanthropist Howard Friesen, ACLU attorney Marshall Krause, Judge Patricia Herron, urbanist Anne Halsted, writer and lawyer Willie C. Gordon, professor Michael Teitz, philanthropist and businessman Herb Sandler, patron of the San Francisco arts Paul Bissinger, economist Lester Telser, and many many more;

- And, we have kept up the educational and outreach activities that are essential if we want the skill of quality oral history interviewing and the knowledge of our projects to spread, enhancing knowledge and the quality of public dialog.

I’ve got another oral history to conduct in the morning, so I’ll resist the temptation to go on — there really a great deal more to tell you about, including the fascinating projects already scheduled for 2019. Instead, I’ll humbly ask that you continue to read this newsletter and keep in touch with us: let us know if any of our interviews proved interesting or useful; if there are projects or specific interviews that you think that we should pursue (especially if you have ideas for how to fund them!); or if you have a question about oral history or any of the many topics which we study and attempt to help illuminate through our interviews. So, please keep in touch. Thank you for a wonderful 2018 and I wish everyone the best in the new year.

Martin Meeker

Charles B. Faulhaber Director, The Oral History Center

The Oral History Center Year in Review: Our Favorite Interview Moments

The Oral History Center has had a productive year, and interviewed many people. Here’s some of our favorite moments from our 2018 interviews. We hope you enjoy them as much as we did!

Martin Meeker:

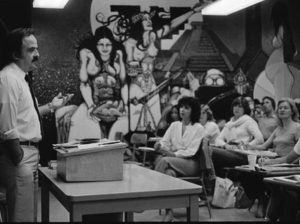

Of the dozens of revelatory, challenging, or even hilarious moments in my interviews this year, I find it difficult to highlight just one. But I keep coming back to this moment in my interview with famed ACLU attorney Marshall Krause. Krause defended a number of individuals charged with obscenity in San Francisco in the 1960s, including Vorpal Gallery owner Muldoon Elder for putting Ron Boise’s erotic Kama Sutra sculptures on display. While recounting the story, Krause mentioned that he had one of the artworks in question, so I asked him to bring it out to show on camera. I then asked him to provide the kind of defense he did in the courtroom in 1964. Krause’s sensitive, insightful, convincing words made it obvious why the jury acquitted Elder of the charges, thus giving Krause and the cause of the freedom of expression a victory.

Amanda Tewes:

My favorite interview moment of 2018 occurred when I interviewed Bay Area herbalist and aromatherapist Jeanne Rose. In the 1960s, Rose was the couturier for bands like Jefferson Airplane and was very plugged into the local rock and roll scene. During one of our sessions together, Rose recounted her experience at the Altamont Speedway Free Festival on December 6, 1969, when an agitated audience of about 300,000 erupted into violence. Rose watched the chaos from above the crowd, but still recalls the strong emotions from that day. Hearing about the event firsthand reinforced how scary and chaotic the events must have been for concert goers. Interestingly, Rose marked this concert as “the end” of rock and roll.

Paul Burnett:

had started an underground called the Werewolves. We spent quite a bit of

time on that for the first few months. I don’t think we ever found any. We

once raided an outfit that were presumably Werewolves. I don’t remember

what happened to them, except that we sort of used movie techniques to make

the raid, coming through the skylights.

Todd Holmes:

My favorite moment this year was interviewing Professor James C. Scott at his farm in Durham, Connecticut. The Sterling Professor of Political Science and Anthropology at Yale University, Scott is widely regarded as one of the most influential thinkers of our time, producing an unparalleled corpus of books over the last 50 years on peasant politics, resistance, and state governance, which today are standard reading across a host of disciplines worldwide. Yet in the interviews, we get a glimpse of the unassuming human being behind the books as Scott discusses the two principles that have always underpinned his approach to academic work – principles he stresses . The first: “Don’t ever be afraid to be an army of one in a crowd of a hundred,” a philosophy of independence he came to embrace during his Quaker education as a young man. The second: “If you’re not having fun, what the hell are you doing?” For those who know Jim Scott, the latter is certainly an oft-quoted remark he has extolled to colleagues and graduate students for decades. Spending the weekend at his farm, I quickly realized that those principles were not just lofty ideals, but words he lived by, and I would be wise to do the same.

Shanna Farrell:

My favorite moment this year was during an interview with WWII Veteran Lawson Sakai, who is in his nineties, for the East Bay Regional Park Parkland Oral History Project. Sakai’s parent immigrated from Japan, making him Nisei, or second generation. He spoke about needing to flee California to avoid internment, and the role that farming in the Central Valley played to rebuild the Japanese community in the aftermath. Driscoll Farms was just getting started and needed help growing strawberries. They recruited Japanese farmers, asked them to farm the land, and split profits with them 50/50. After hearing how Driscoll helped many people get back on their feet after losing everything in the wake of Executive Order 9066, I scoured my food history books and didn’t find any information about this. I felt like I had stumbled upon a hidden historical gem.

Roger Eardley-Pryor:

Interviewing Aaron Mair—the 57th president of the Sierra Club and the Club’s first African-American president—provided my favorite interview moments this year. We conducted Aaron’s initial interview session at the Hagood Mill Historic Site in the upcountry of South Carolina. As his family’s genealogist, Aaron has the 1865 records of his enslaved great, great grandfather Zion McKenzie’s emancipation from the Hagood family. Before interviewing at the Hagood Mill site, Aaron and I visited the humble, un-fenced cemetery of his enslaved ancestors, whose rough, uncut gravestones lay just outside the Hagood family’s iron-fenced grave site with grandiose tombs and Confederate soldier crosses. Later, during his interview, Aaron recounted his ancestors’ remarkable stories from slavery to freedom and their purchase of farm land that remains in Aaron’s family today. His family’s narrative, from human dominion to sustainable stewardship of land, informs Aaron’s ideas on environmental responsibility. And it helped inspire Aaron’s initiatives as Sierra Club president to unify activism for environmental rights with civil rights and labor rights. Aaron takes seriously Sierra Club founder John Muir’s admonition that “When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe.”

Mair and Eardley-Pryor

OHC Commences Project to Commemorate 50th Anniversary of Chicana/o Studies

by Todd Holmes

Today, courses on the Mexican American experience can be found at nearly every college campus across the nation. In an academic environment long entrenched within the mold of Western Europe, such curriculum is nothing short of a miraculous testament to the diversification of American education. Indeed, the subject has its own journals, national organizations, student groups, academic departments, and specialized degrees. Yet fifty years ago, the discipline of Chicana/o Studies—as the field of study became known—was just taking shape and, above all, struggling for legitimacy.

To commemorate the 50th anniversary of the discipline, the OHC initiated the Chicana/o Studies Oral History Project. Led by Todd Holmes, the project documents the historical development of the field through in-depth interviews with the first generation of scholars who shaped it. Holmes began working on the project in the fall of 2016 with the initial step of putting together an advisory council composed of Chicana/o scholars from around the country. Based on the council’s recommendations, over 25 prominent scholars were selected to be interviewed—scholars whose pioneering research and innovative work played a significant role in building the discipline over the last five decades. Holmes then commenced an ambitious fundraising campaign, going directly to the home universities of the featured scholars. To date, the project has received generous support from a host of academic institutions, including the University of California Office of the President, California State University Office of the Chancellor, Stanford University, Arizona State University, and the University of Texas at Austin.

The interviews will offer an important look at the formation of Chicana/o Studies, as well as the experiences of those who built it. Such areas of discussion include their family background, undergraduate and graduate experiences, and academic career as faculty members. With most—if not all—of these scholars standing as the first in the families to attend college, and certainly among the first cohort of Mexican American graduate students and faculty, their experiences highlight the evolution of the field, the diversification of higher education, and the long struggle that underpinned both. Moreover, the interviews trace significant shifts within the field of Chicana/o Studies over the decades, and how the field expanded from college campuses in California and Texas to a nationally recognized discipline of study.

All interviews are slated to be completed by the summer of 2019. When done, they will be featured on a dedicated page of the Center’s website. Moreover, the oral histories will form the heart of a documentary film, tentatively titled, Chicana/o Studies: The Legacy of A Movement and the Forging of A Discipline. The OHC is thrilled to make this foray into film and collaborate with veteran producer Ray Telles and others in this exciting effort. Stay tuned for further updates in 2019!

First Generation Scholars

Norma Alarcón (UC Berkeley)

Tomás Almaguer (San Francisco State)

Rudy Acuňa (CSU Northridge)

Mario Barrera (UC Berkeley)

Albert Camarillo (Stanford)

Martha Cotera (UT Austin)

Antonia Castaňeda (St. Mary’s College)

Edward Escobar (Arizona State)

Juan Gómez-Quiňones (UCLA)

Mario T. García (UC Santa Barbara)

Deena González (Loyola Marymount)

Richard Griswold Castillo (San Diego State)

Ramón Guitierrez (University of Chicago)

José E. Limón (UT Austin)

David Montejano (UC Berkeley)

Emma Pérez (University of Arizona)

Ricardo Romo (UT San Antonio)

Raquel Rubio-Goldsmith (University of Arizona)

Vicki Ruiz (UC Irvine)

Ramón Saldivar (Stanford)

Rita Sanchez (San Diego State)

Rosaura Sánchez (UC San Diego)

Carlos Vélez-Ibáňez (Arizona State)

Emilio Zamora (UT Austin)

Patricia Zavella (UC Santa Cruz)

For more information on the project, its participants, and to view the film’s trailer, visit the project page..

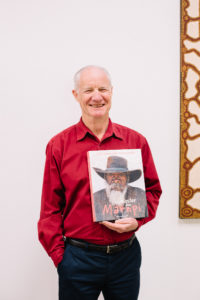

OHC Advanced Oral History Summer Institute Alumni Spotlight: Alec O’Halloran

We recently caught up with one of our Advanced Oral History Summer Institute alums, Alec O’Halloran, who recently published a book that was influenced by his work with us. His book, The Master from Marnpi, is based on oral history interviews. O’Halloran reflects on his work, his time with us, and the release on his book.

(Applications are open now for the 2019 Summer Institute from August 5-9. Apply now!)

Q: How did you first come to oral history?

I don’t have a ‘first’ recollection. I’ve always been interested in stories and in the 1990s (in my forties) I was drawn to the larger story of Aboriginal art and history in Australia, which I knew very little about. This led to reading autobiographies and biographies of Indigenous people, as well as attending art exhibitions etc. Oral history interviews were often quoted in stories about Aboriginal artists, particularly older people from remote parts of Australia that most of our population knew very little about.

When I began researching the life of an artist whose work I admired, Mick Namarari Tjapaltjarri, I found out he had done two recorded interviews in his language, Pintupi, a decade before he passed away (1998). I found those interviews – or their translated transcriptions – fascinating! What a life he had led… so different to mine. Those interviews motivated me to look around for more oral history work that engaged with Aboriginal artists in particular.

Q: Tell us a little bit about the project you were working on when you attended the Advanced Oral History Summer Institute.

I attended the Institute in 2010, in part with support of a travel grant from my institution, The Australian National University in Canberra, where I was undertaking a doctoral program in Interdisciplinary Studies. My thesis project was the life and art of Mick Namarari Tjapaltjarri. I had a rough draft of his life story by that stage, and I was mostly preoccupied with assembling the chronology of events, rather than comprehending his character.

Q: How did your work benefit from the Summer Institute?

One thing I still remember from one of the guest lecturers was about ‘listening and hearing’ when working with recorded interviews. And with so many conversations with fellow participants about each other’s projects, I realised I was not fully engaging with the materials I had at hand. So, I when I returned home to Sydney I took a more rigorous approach.

I went back to the original recordings of Namarari (one audio, one video), and the transcripts, and tasked myself to see and hear more than I had before. To not only track events and incidents and the chronology of his life story, but to look beneath and between the lines and sounds for character and personality traits, for nuanced references to culture, to allusions to relationships with other people. I said to myself, ‘These two interviews are like gold, I need to use them to the fullest’. So the Institute motivated me to be much more dedicated to the oral history component of the biographical research about Namarari’s life and art. This certainly improved the quality of my writing when I was integrating Namarari’s voice into a wider story that involved multiple voices and archival sources.

Another outcome too. Oral history as a data-making history-creating method became more important to me. I don’t think I was an expert practitioner, so I tried to improve the quality of my interviewing work. This involved better planning of interviews and better conduct as the interviewer. Also, I saw that I had an opportunity to contribute to the field in a meaningful way.

The region where Namarari lived is called the Western Desert. It occupies a vast swathe of Central Australia. (Bigger than Texas!) My field work took me to that region, first by air to Alice Springs, and then by four-wheel drive (essential for the outback gravel roads). I realised I could do additional oral history work outside my specific research project as part of my travels. During 2011-13 I was awarded two oral history grants by the Northern Territory Government, which I applied to producing two community oral history reports: for the desert communities of Mount Liebig and Kintore. I interviewed some twenty Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people and submitted a report, and deposited the interviews with the Northern Territory Archives Service in Darwin. I hope that one day a community member or researcher will come along who wants to write a local history of those places and find those interviews… they can then serve a good purpose. Importantly, but sadly, some of the people I interviewed have passed away.

Q: What’s the status of your project now?

My project, to produce an authorised biography on the life and art career of Mick Namarari Tjapaltjarri, is complete! The master from Marnpi was released on 7 September 2018.

See my website for more information www.alecohalloran.com

Q: How did your biography, The Master from Marnpi, benefit from the use of oral history?

Namarari passed away in 1998, before I started my research, so I never met him and I could not interview him. This contrasts sharply with the majority of Aboriginal artist’s biographies in recent decades in Australia – they are invariably deep collaborations between the author and subject.

My narration of Namarari’s life story is based on his testimony: two interviews recorded in Pintupi, in 1989 and 1992, each conducted in the Western Desert by non-Aboriginal researchers who had travelled there for that purpose (and to interview other Aboriginal people of the area).

Thus it is his (translated and transcribed) voice that runs through the chapters. The many gaps are filled, where possible, with other oral history interviews I did with his relatives, and with art advisers who worked with him across his art career (1971-1998). I also drew on other oral histories, both my original interviews and from the archives, to enrich the narrative, applying more details to local histories of place, and shining a light on prevailing attitudes and circumstances that Namarari and his Aboriginal countrymen found themselves in. Where possible, I added salient photographs from a wide range of archives to illustrate what was referred to in the text by people who were ‘there at the time’.

Q: You have some visual components in the book, like maps. How did you weave visual elements with oral history?

The non-text items are: maps (of Australia, and the Western Desert region where Namarari lived), diagrams (eg, the Aboriginal kinship system), tables (eg, Namarari’s annual art output from 1971 to 1998), photographs of people, places (eg, desert scenes, Namarari’s house), and art (primarily his paintings).

The visual components serve to show the reader something of what the story-teller (eg, Namarari or his relatives) was talking about. If it was an important water-source location from his childhood in the 1930s, I would include a photograph. If it was a settlement where he lived in the 1950s, I would look for appropriate pictures from that era. Unsurprisingly there are many more useful photographs from the 1990s than the 1950s.

I applied a policy of sorts to the inclusion of images: it had to illuminate something in the text, rather than being a decorative piece to fill a space. I sometimes juxtaposed images to make a point, such as two artworks that had a subtle feature in common.

Q: What kind of projects do you draw inspiration from?

I have really been preoccupied with my book for several years, so I haven’t been looking for extra inspiration. When I was doing the biographical research I drew inspiration (and understanding) from reading Indigenous autobiographies… they often had the raw truth of historical circumstance from the mouths of those who experienced events and situations and policies.

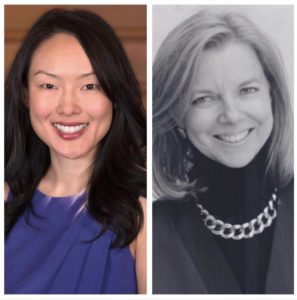

Women in Politics Panel Discussion with Jane Kim and Mary Hughes Event Recap

By Amanda Tewes, OHC interviewer

In last month’s midterms elections, a wave of diverse women swept into political office across America. From local school boards to Congressional and gubernatorial races, women showed up this November. While many may point to this result as the culmination of women’s dedicated activism since 2016, in places like the Bay Area, well-established political organization helped pull women candidates over the finish line.

On Tuesday, November 13th, one week after the polls closed, OHC staff and local political buffs met at The Ruby to discuss the historical and contemporary role of political women in the Bay Area and to help kick off the Women in Bay Area Politics Oral History Project. The event featured a panel discussion with political consultant and Close the Gap California founder Mary Hughes and San Francisco Supervisor Jane Kim. From their combined years of experience, Hughes and Kim shared insight into what it’s like being a woman in Bay Area politics.

One great question from the audience asked the panelists about how women balance family obligations and political careers. Hughes recalled overhearing a recent conversation in which a woman was praised for waiting to run for office until her children were older. Hughes was dismayed to realize these double standards still existed for women in 2018, and noted that men do not face similar criticism. Similarly, Kim explained that her office is full of working mothers, and that while this was a challenge to balance at first, it also has helped productivity during normal work hours.

Hughes also reminded the audience that while women’s campaign successes are nearly on par with that of men, the struggle often occurs when trying to convince women to run for office in the first place. Even when they are extremely qualified, some women need to be asked more than once. Hughes praised Kim for continuing to run and participate in politics, even after setbacks. She explained that dusting yourself off and trying again is important in order to push toward gender equality in political office.

The stories Hughes and Kim shared reinforced the need to document the histories of Bay Area political women in order to get a clearer picture of the breadth of political work women have been doing on the ground and behind the scenes. Now is the time to undertake this endeavor to celebrate and learn from Bay Area women who have shaped local and national politics.

Please help us out by suggesting women narrators whose political work has been unsung! Which stories about women in politics aren’t making it into the historical record?

To support the Bay Area Women in Politics Project, visit ucblib.link/givetoOHC. Please note under special instructions: “For the Bay Area Women in Politics Oral History Project.”

If you would like to learn more about the project, please contact Amanda Tewes at atewes@berkeley.edu.

11/13 Event: Women in Bay Area Politics Panel and Discussion

By Amanda Tewes, OHC interviewer

Join us on November 13, 2018, 6-8 PM at The Ruby, a women’s creative working space in San Francisco! The festivities feature a panel discussion with Supervisor Jane Kim and Close the Gap California founder Mary Hughes.

1992 has been dubbed “The Year of the Woman,” a phenomenon in which a wave of women candidates swept local and national races for public office. California led this charge by becoming the first state in American history to be represented by two women senators—Barbara Boxer and Dianne Feinstein.

And yet, 1992 was not the beginning of women’s political activism, but rather the culmination of decades of organization encouraging women to get involved and run for office. For generations, Bay Area women have built the foundations of political activism that span neighborhood organizations to support networks. And their stories inform our present.

As engaged citizens, we need to know more about these women who helped create a space for themselves in Bay Area political life. What drives women to run for elected office, to fight for affordable housing and environmental regulations, to fundraise for women candidates? What challenges and successes have women encountered in politics?

In order to document these stories, I am developing the Bay Area Women in Politics Oral History Project to record the history of these local women and their impact on and journeys through politics. The Oral History Center continues to preserve stories about California politicians, but this project is unique in that it focuses on women in one geographic region in order to get a clearer picture of the breadth of political work women have been doing on the ground and behind the scenes.

This topic is both historical and part of a contemporary conversation about the role of women in American politics. Given this surge of women in politics and the upcoming hundredth anniversary of women’s suffrage, now is the time to undertake this endeavor to celebrate and learn from Bay Area women who have shaped local and national politics.

Join us to kickoff this the Bay Area Women in Politics Oral History Project with an event on November 13, 2018, 6-8 PM at The Ruby, a women’s creative working space in San Francisco! The festivities feature a panel discussion with Supervisor Jane Kim and Close the Gap California founder Mary Hughes.

Advanced Oral History Summer Institute Alum Spotlight: Kelly Navies

We recently caught up with Kelly Navies, who joined us in 2013 for our Summer Institute. She is now the Museum Specialist in Oral History at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, where she coordinates their Oral History program. We talked to her about how she came to oral history, what she learned at the Institute, and her current work with the Smithsonian.

Q: How did you first come to oral history?

A: I first came to oral history, while I was an undergraduate at UC Berkeley in the African American Studies Department back in the early 1990s. In the Fall semester of my senior year, I took two courses which had a profound impact on my life; African American Poetry with the late June Jordan, and Images of Black Women in Literature with the late Barbara Christian. Prof. Christian assigned an optional paper to write about a maternal ancestor who’d lived during the 19th century. At the same time, June ( she preferred to be called, June), assigned a poem about mothers. Receiving these two assignments at the same time, inspired me to decide to pursue a research project on a maternal ancestor my mother had been telling me about all my life, but whom she actually knew very little about. All she knew was that she had been enslaved in Asheville, NC and had lived over 100 years into the 1950s, when my youthful mother had actually met her. At the time, all 6 of my grandmother’s siblings were still living ( she was deceased), so I embarked upon an oral history project to interview them all about their grandmother. Through a combination of genealogical research and oral history interviews, I eventually learned that she was named, Elizabeth Gudger Stevens, had indeed been born into slavery in Asheville, NC and had lived until 1956, when she was either 102 or 106, depending on who you believe ( no birth records, of course). It must be added that the only reason I knew “oral history” was a thing at all was because of a 7th grade English assignment and being introduced to Zora Neale Hurston at an early age.

Q: You attended the Advanced Oral History Summer Institute in 2013. What project were working on?

A: When I came to the Advanced Oral History Summer Institute in 2013, I was working as a Special Collections Librarian and Oral Historian for the Washington DC Public Library System. I had received an MLIS grant to pursue the “U Street Oral History Project.” The U Street corridor was the thriving heart of the African American business and cultural community in Washington, DC up until 1968, when many of the businesses were destroyed during the urban upheaval that followed the assassination of Dr. King. In fact, it remained a central location for Black life in Washington, DC up until the recent demographic transformation that has marked the city. For this project, I conducted over a dozen audio interviews that are now available from the DC Public library website: (dclibrary.org) Three audio clips from this project have been made into podcasts that are also available from the DC Public Library website. I also held a public program at the Busboys and Poets restaurant on 14th St., right off of the historic U Street corridor, where I invited interviewees to participate. Finally, I shared the research project on a radio program at WPFW.

Q: How did your work benefit from the Summer Institute?

A: The Summer Institute introduced me to the work of other oral historians from around the world working in a variety of disciplines from academia to independent scholars and artists. I have kept in touch with several, in fact. It also brought me up to speed on the technological and theoretical state of the field. Finally, I really enjoyed learning about Robin Nagle’s oral history work with sanitation workers.

Q: You now work with the Smithsonian. What’s the role of oral history at the museum?

A: As Museum Specialist in Oral History here at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC), I coordinate the oral history program, which involves planning, budgeting, developing projects in collaboration with curators, and yes, interviewing. All of our interviews are filmed. However, I don’t conduct all of the interviews- in some cases, I conduct the research, help develop the questions, and handle the logistics. I also do trainings for classes and community groups.

Q: How do you get the public to engage with oral history?

A: Our oral history collection is cataloged along with other artifacts and are available for use in exhibitions for as long as we preserve them. Most recently, we conducted interviews for the Poor People’s Campaign Exhibition, City of Hope, and clips from those interviews were included in the exhibition. Visitors to the museum will also find oral history interviews located throughout the museum. For example, in our community galleries on the third floor, there is a clip of an interview I conducted with Mr. Frank Wright about his family’s generational involvement in oyster fishing on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. The oral history program also includes thousands of recordings captured in our Reflections Booths which are located in the history galleries. Here, visitors choose a question and record their answers in two minutes or less on a built-in camera. They then can choose to email it to themselves and/or share it with us.

The Community Curation Project is sponsored by the Smith Fund. Also, the full name of the Poor People’s Campaign exhibition is: City of Hope: Resurrection City & the 1968 Poor People’s Campaign. It is curated by Aaron Bryant and is on view at the National Museum of American History.

Q: What do you hope the public takes away from the oral histories in the Smithsonian’s collection?

A: When visitors encounter oral history in the museum, I hope they understand that history is a living breathing thing and not just something you read about in books. I hope it increases their awareness and interest in the stories of their elders and others around them.

Q: What kind of projects do you draw inspiration from?

A: I find all of my projects/interviews inspirational. The oral histories of African Americans reveal deep truths about America and about the human condition, overall. Each story I capture reminds me that there are so many other stories. oral history is a passion that is endlessly gratifying. Most recently, I had an experience that speaks to the significance of recording these stories. I interviewed a woman who knew that she wouldn’t be with us much longer-a black woman who had accomplished much in her life, and yet was still worried that her work might be forgotten-her narrative was profound and reflective. She passed away not long after and her family asked me to share some of what I had learned about her life at the memorial service. I truly consider the work we do, as oral historians, to be a sacred honor. We facilitate and capture heroic stories of ordinary individuals that are often relegated to the margins.

OHC Director’s Column, November 2018

The Oral History Center is excited to announce that we have joined forces with local public radio station KQED on a significant new partnership. The occasion for this collaboration is a new oral history of four-term California governor Jerry Brown. The project is expected to encompass at least 30 hours of conversations with Brown, taking place over a series of months, beginning later this year. The interviews will span most of Brown’s adult life, including his time in the seminary, lessons learned from his father’s governorship, his terms as secretary of state, attorney general and governor of California, and mayor of Oakland, and three presidential bids. They will address a life lived in and out of the public eye, and a long and extraordinary career devoted to public service.

Research and interview duties will be shared by my colleague, Todd Holmes, and I. We’ll be joined by Scott Shafer, senior editor for KQED’s Politics and Government Desk and co-host of the weekly radio program and podcast Political Breakdown. “Jerry Brown is a singularly important figure in California political history,” Shafer says. “His long and remarkable time in and out of public life in California, including his personal reflections and insights, should be documented for posterity, and we’re delighted to be a part of doing just that.”

The final interviews will join our collection of political oral histories, which include major interview projects on four earlier California governors, including Jerry’s father Pat Brown, who was elected in 1958 and again in 1962. Transcripts and audio and video of the Brown interviews will be made available on our website. We are thrilled to partner with KQED to see that Governor Brown’s oral history is completed and made available to everyone — and we are humbled to be the ones with the honor of making sure that this history is recorded and preserved.

Like all Oral History Center projects, we are obliged to raise funding to help support this endeavor as neither the state or the university will provide funding this extraordinarily important project. We are happy to accept donations large and small for those who agree that this oral history needs to be recorded and that we cannot miss this window of opportunity to get it done. Please contact me directly (mmeeker@berkeley.edu or 510-643-9733) with questions or think about making a donation online: http://ucblib.link/givetoOHC

Martin Meeker, @MartinDMeeker

Charles B. Faulhaber Director

Oral History Center