By Kim Bancroft

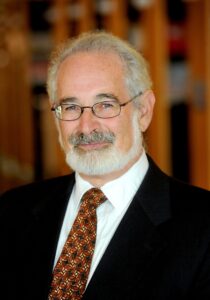

By no means was Malcolm finished. He still had work to do, come the hell of Parkinson’s and the high water threatening to stifle his voice, his mobility, his agility. Yet he forged ahead. Malcolm Margolin, the founder of Heyday Books, writer extraordinaire, and supporter of innumerable Indigenous, environmental, literary, historical, and arts projects for fifty years, passed away on August 20, 2025. Several obituaries have already extolled Malcolm’s wonderful contributions in the Bay Area and across California. Caretaking nature inspired his early works, leading to his creation of Heyday Books in 1974. That press and his lively personality attracted an array of writers, craftspeople, Indigenous culture bearers, environmentalists, and more.

In 2017, The Bancroft Library became a recipient of Malcolm’s archives. He highly respected this temple of literary riches. The respect was mutual: In 2008 Malcolm received the Hubert Howe Bancroft Award for his contributions to California literature and history. Marking those contributions are 75 cartons of Heyday archives, one box and two cartons of Malcolm’s personal archives, and the interviews I did with him for over two years about his life and work.

My friendship with Malcolm was initiated thanks to his daughter Sadie, who attended my English class at Merritt College. Based on my responses to her essays, Malcolm invited me to edit a couple of memoirs that came his way. Eventually I asked when he would write about his own storied life.

“Oh, I don’t have time for that!”

Unacceptable! So I offered to record his tales. I’d long been fascinated by capturing oral histories because of my great-great-grandparents, H.H. and Matilda Bancroft who, in the late 19th century, had eagerly copied down reminiscences of pioneers of the West. In October, 2011, Malcolm began recounting with me his life trajectory, from growing up in Boston where he was born on October 27, 1940, to what it meant to face the end of his time at Heyday in 2014, with many adventures and illustrious people encountered in between. I’ve never claimed to be an oral historian, given the formal training one can undergo to don that title. But Malcolm and I had developed a shared sense of humor and depth that made rambling through a variety of topics easy and intriguing. Those interviews are now available online and lodged at the renowned Oral History Center collection at The Bancroft, titled: ‘Such a goddamn beautiful life,’ Conversations about Heyday Books and Everything Else.

From those interviews came his biography, including passages from forty more interviews with staff, authors, family, and friends. The Heyday of Malcolm Margolin: The Damn Good Times of a Fiercely Independent Publisher came out in 2014 (a Commonwealth Club California Book Award winner that year), in time for Malcolm to celebrate his forty years with Heyday. Meanwhile, Heyday found a perfect new director in Steve Wasserman, a Berkeley native with writing acumen and editorial connections developed at Yale University Press, among others. With Steve’s leadership and ever dedicated staff, Heyday continues to have a remarkable impact on California publishing and support of California Indian culture.

Still driven, Malcolm initiated the California Institute of Culture, Arts, and Nature (Calif I CAN). Malcolm’s old friend and lifelong environmental, peace, and arts activist Claire Greensfelder helped in that effort and then became Calif I CAN’s hardworking executive director. By 2022, with Malcolm’s avid input, even from a bed when he could no longer walk on his own, Calif I CAN had developed multiple and significant ventures, including the annual California Native Ways and Berkeley Bird Festivals in Berkeley, a project to “remap California” in an atlas of original Indigenous names, and a book about West Berkeley’s historic Shellmound and the effort to save it from being built over with an apartment complex.

Despite all that activity, Malcolm still had plenty of time to muse while at his nursing facility, dependent on others for mobility. His ever-present and self-described “dreaminess” now led him to envision unearthing gems from his archives and those of Heyday to find more material for publishing, especially in order to highlight the many captivating people he had come to know through Heyday. Ironically, in 2008 when the Heyday staff was preparing to move from the Koerber Building on University Avenue to its next location, the fate of the Heyday archives was in question. Patricia Wakida, then on the staff, recounted arriving on a Monday morning to learn of Malcolm’s “purge” of their file cabinets. Patricia asked, “How was your weekend?” Malcolm replied, “Oh, I just threw out all my s—.” Meaning he had thrown boxes of Heyday papers into the dumpster out back. “What?!” she cried, in shock. “Shouldn’t you be putting it in The Bancroft Library or somewhere?” Apparently, Malcolm just laughed and said, “Yeah, I think Kevin Starr is going to be really mad at me.” Historian Kevin Starr, Malcolm’s friend, was also the California State Librarian.

Fortunately, Malcolm hadn’t thrown out all the files that documented Heyday’s history of its collaborations with writers and their manuscripts, letters, and more. In 2017, The Bancroft Library received that treasure trove of creativity in many remaining archives. Ever creative, curious and ambitious, Malcolm sought in the last two years of his life to make something from that cache of papers. Because he depended on others for mobility in those last years, “Malcolm had more time to think about his legacy,” Claire noted. He engaged Pam Michael to help sort his papers into meaningful files, and Claire Greensfelder worked assiduously with him at the Library itself as Malcolm sifted through boxes and cartons in search of the next book project, and the next.

I accompanied Malcolm on an early trip to The Bancroft to create an inventory of his papers, which included items from his early writing forays in the 1960s on: college papers, notebooks, manuscript drafts, poetry, random essays. I’d extract a file, type a description of its contents, and sometimes read aloud an amusing title and a few sentences. Malcolm would laugh, then share a tidbit of the memory just pulled from his past. Some examples: “A Hundred Thousand Orgasms 1968-1969 (more innocent than it sounded),” “The Education of a Seattle Cabbie 1969” (as harrowing as could be anticipated), and “The Wilderness Beneath the Slash Pile 1970” (showing his ever-environmentalist connections to the earth).

Malcolm was able to continue his explorations at The Bancroft, along with other projects around Berkeley and beyond, because of the superior support he received from family and friends, especially from his caregiver David Scortino and writing assistant Pam Michael. David gently maneuvered Malcolm in and out of his wheelchair and navigated him everywhere, including into The Bancroft Library’s small conference room where he, Claire, and Malcolm worked twice a month for two years. After their two hours of research, they’d have lunch on campus, either at the Free Speech Movement Café or the Faculty Club, often arranging to meet someone with whom Malcolm wanted to exchange news and ideas. David made movement and meals “seamless,” according to Claire. Of his time with Malcolm at the library, David wrote, “The Bancroft wasn’t just a building or connection that made Malcolm’s work more enjoyable. It was a village that made it possible.” Claire also sang the praises of The Bancroft Library staff who welcomed these archival archaeologists with great warmth. One book has already come from the archives, an anthology of Malcolm’s writing about his encounters with Native peoples: Deep Hanging Out: Wanderings and Wonderment in Native California (Heyday, 2021).

More scintillating writing shall be revealed. Said Claire, “Malcolm knew a gold mine lay in all those letters with authors who had become part of Heyday, along with their writing, photos, and other intriguing ephemera, like event posters. It made Malcolm incredibly happy to revisit those forty years with Heyday. “Also, going there allowed him to get out of his bed and room at Piedmont Gardens, where he was treated well but felt so limited compared to what his life had been.” Now he could see himself again in the role of a professional culture bearer. “He was so grateful for that opportunity, and for the support of the staff at the Library.”

The work remains of digitizing all of Malcolm’s archives and those of Heyday, not to mention additional records compiled by Calif I CAN, requiring the raising of funds. Over the summer, an intern named Robert West helped scan some of the multitudinous communications in the archives, with Malcolm’s ultimate hope of publishing a book of key correspondence. Said Claire, “Looking at the letters exchanged between Heyday staff, Malcolm, and writers, you get a sense of their breadth of knowledge and networking, their delight in their work. What a phenomenal influence Heyday has had across the state and beyond!”

I like to think of Malcolm Margolin’s laughter still ringing out from the small conference room and pouring into the Reading Room at The Bancroft Library where his words and deeds will live on, as we cherish all kinds of archives preserved there.