Author: Shanna Farrell

The Oral History Center is pleased to announce our inaugural UC Graduate Student of Color Fellow, Rudy Mondragón, for Summer 2019!

Mondragón is a doctoral candidate at the University of California, Los Angeles working on a project that looks at the sport of boxing and the ways in which black and brown boxers politically and culturally express themselves via the famous ring entrance. Academically, Mondragón has written reviews of the boxing documentary “Champs” for the Journal of Sports History and Louis Moore’s I Fight for a Living: Boxing and the Battle for Black Manhood, 1880-1915, for the International Review for the Sociology of Sport. He has also written on boxing for Remezcla, We Are Mitú, and L.A. Taco and has been quoted in CNN and Bleacher Report articles and interviewed by ESPN Deportes-Seattle. More recently, he contributed an article and photographs of professional boxers José Carlos Ramírez and Carlos “The Solution” Morales for The Streets Magazine. Mondragón is the recipient of the prestigious University of California Cota Robles Fellowship, NCAA Ethnic Minority Enhancement Postgraduate Award, and Arthur Ashe Jr. Sports-Scholar Award. In the summer of 2017, Mondragón was a Fellow of the Smithsonian Latino Museum Studies Program in Washington DC where he conducted interviews for the Latinos and Baseball Project.

A Word from Mondragón on His Project:

My research advances conversations in the fields of critical sports studies, Chicana/o/x studies, cultural studies, and American studies. I explore the sport of boxing and the ways in which professional fighters deploy expressive culture (music, style, fashion, and entourages) in their ring entrances. I conceptualize the ring entrance as a political site of struggle where boxers communicate new forms of subjectivities and identities, and at times, both overtly and covertly perform dissent and resistance to dominant ideologies and structures of power. Given that boxers navigate a hyper-capitalist and neoliberal sporting industry that is unregulated, I argue that boxers are vulnerable pawns that navigate a shifting sports market as well as the effects of dominant ideologies of race, gender, sexuality, and poverty. For me, the ring entrance has spatial dimensions of infinite possibilities that allows fighters to subtly and creatively reimagine an alternative world and liberation.

All photos by Rudy Mondragón

We recently caught up with Mondragón to ask him about his background, how he became interested in boxing, and who he plans to interview this summer.

Q: Tell us a little bit about yourself. Where do you go to school and what are you studying?

I am in the fifth year of my doctoral studies at the University of California, Los Angeles. I am working on my PhD in Chicana and Chicano Studies. When I first started my studies, I was planning on conducting a 16th century cultural history on indigenous communities in Central Mexico to interrogate race and religious hegemony. That didn’t really work out [chuckle]. I have always been passionate about boxing. A couple of weeks into my first quarter of graduate school, I realized that I had not watched a single boxing match in over a month. Something clicked in my mind and heart. I mentally checked out of the seminar and started writing down my ideas about how boxing could be an area of study that would allow me to interrogate race, history, stories, culture, and athletic-activism. I was excited but also worried that my ideas would not be accepted. That’s when I decided to talk with Dr. Gaye Theresa Johnson. I trust her greatly, so we scheduled a Skype meeting, so I could share my new research vision. I’ll never forget what happened during our talk. As I shared my ideas, Dr. Johnson reached over the table and grabbed a book. She put the book in front of her laptop camera, so I could see the cover. The book was about women and boxing! It was the sign I needed to pursue this area of study. Dr. Johnson is now the chair of my committee.

Q: How did you become interested in researching professional boxing?

My parents got me into watching professional boxing. I was 7 years old in the summer of 1992. This was the year that the Fight of the Century was to take place between Julio Cesar Chavez and Hector “Macho” Camacho. The fight was being advertised everywhere. My mother would always have a Spanish print of the local television listings. I remember the September issue of that print featured both boxers on the front cover. It was my mom who indirectly put me on to boxing. On the night of September 12, 1992, my father took me to my uncle Felipe’s house for the big fight. As a working-class family, the reason we went to his house for the fight was because he had a black box, which was a device designed to gain illegal access to all cable television channels. This meant that pay-per-view events, like this fight in particular, would not cost my uncle a single dime. I remember rooting for Chavez because his Mexican nationality was similar to my father’s. I wanted Chavez to win, but as I watched some of the behind the scenes footage from Camacho’s dressing room, I began to gravitate towards the Puerto Rican fighter. He was flamboyant, flashy, loud, and full of energy. He had a boxing outfit that resembled a Captain America suit. The only difference was that on the back of the red, white, and blue outfit was a huge “M” for Macho. His suit was representative of Captain Puerto Rico or Captain Macho. It was really awesome because it was a proud statement about who he was. As Camacho made his way out his dressing room and towards the tunnel to start his ring walk, the sounds of McFadden and Whitehead’s “Ain’t No Stopping Us Now” blasted inside the Thomas and Mack Center in Las Vegas. I remember seeing Puerto Rican flags in the stands, fans were dancing, and Camacho’s mom had her hands raised in the air as her son danced his way to the ring. I didn’t know it at the time, but that was the moment where my research on professional boxing got started. Since then, I’ve never stopped watching, studying, discussing, and now, writing about and photographing the world of boxing.

Q: You’re planning to interview Fernando “El Feroz” Vargas, a two-time light middleweight world champion who boxed from 1997 – 2007. How did you choose him and what topics and themes are you hoping to explore with him in your interview?

I was 17 years old when I first watched Fernando Vargas (AKA El Feroz and The Aztec Warrior). This was in 2002, a year after the September 11 attacks in New York. This match was one of Fernando’s biggest career fights. He was going up against Oscar De La Hoya, a fighter that I was a huge fan of. Seventeen-year-old me was thrilled to watch De La Hoya fight against Vargas. Part of my fandom for De La Hoya was due to my alignment with De La Hoya’s identity performance. Oscar was the definition of the American Dream for some Mexican Americans. He is what the boxing world considers a corporate fighter, which in his case, meant he cultivated his career as a clean-cut corporate friendly fighter who performed a respectability that made him consumable by Mexican American middle-class and usable by corporate brands. It wasn’t until I got older and began to take Chicana and Chicano Studies courses that I realized why Fernando Vargas’s performance of identities was so important. Vargas’s fight with De La Hoya took place in the post-9/11 moment. This was a moment in which Michael Silk describes as a time in history where “dissent was silenced, a time in which it was not possible to fully articulate a sense of being American outside that which was normalized.” It was also a time when US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agency was formed and the number of noncitizens detained in detention centers skyrocketed. Rather than assimilate to the political moment, Vargas entered the ring for his fight against De La Hoya in an unapologetic, courageous, and creative manner. He walked to the ring to live Mexican ranchero music, wore the colors of the Mexican flag, and was sponsored by DADA, a brand that was popular among hip hop communities. The media and fans often described him as a thug because of the way he dressed, his bald head, and his masculine bravado. This unapologetic performance in the post-9/11 moment is why Vargas matters as he can teach us a great deal about the ways in which subtle resistance can be performed within a sports and political context through the deployment of expressive culture. In his case, music and fashion.

As such, some of the themes I hope to explore are Fernando’s autobiography, particularly his childhood when he lived in the agricultural city of Oxnard, California and how he found the sport of boxing. Often, boxing is a sport that recruits people from low-income and poverty. For a select few, boxing serves as a vehicle out of poverty. I also want to explore his relationship with his former trainer, The Big G, who has had a huge impact on Fernando’s life both in and out of the ring. Fernando was also known for his ring entrances that featured the song “No Me Se Rajar” (I do not quit), Aztec pyramid stones that he would punch through to get to the boxing ring, and the use of Mexican and Aztec symbols for his ring attire. By exploring Fernando’s ring entrances, I will be able to explore Fernando’s multiple identities and how those informed the curation of his ring entrances. And finally, I want to center his experience as a boxer who fought in the pre-and post-9/11 moment. In particular, I want to learn more about his claims to dignity and cultural pride during this historical period.

Q: What are you most excited to get out of your fellowship with the OHC?

The timing of being awarded this fellowship was terrific. I just defended my dissertation proposal, making me a doctoral candidate. As I am on the eve of conducting interviews with professional boxers for my dissertation project, this fellowship will allow me to gain necessary guidance from Shanna Farrell. It will also give me a hands-on experience in conducting the longest oral history to date in my career. I am excited about this because I will have experts from the Oral History Center providing me with direction, feedback, and critique that will help refine my current skill set and strengths when it comes to conducting interviews and oral histories. I’m also excited to contribute the first oral history with a professional fighter to be archived at a prestigious research library.

OHC Director’s Column, April 2019

Documenting the history of the University of California is an endeavor that we take very seriously at the Oral History Center. As a result of our work over the past sixty-five years, we have conducted hundreds of in-depth interviews in which some key facet, influential individual, or impactful event of the university is narrated and explained. Hundreds more interviews (1,995 according to our search tool) at least mention the university in passing, providing anecdotes that further expand the archive of first-personal testimony about the university. The University of California’s history is among the best documented in the world because these numerous and diverse voices were recorded by the Oral History Center and archived at the Bancroft Library.

All the more remarkable is that we have done this work with very little dedicated university support. Certainly we have received occasional funding from the UC Office of the President, this or that college or department, or a benefactor who wants to underwrite a specific interview. These type donations, in fact, are responsible for the vast majority of University of California oral histories that we’ve done, and we are grateful for the continued support of those who recognize a need for an interview and work with us to make it happen.

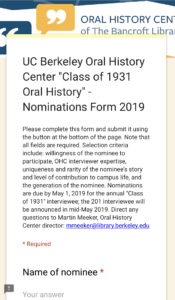

This works well enough, except in those instances in which we identify a key individual who needs to be interviewed but for whom there is no clear benefactor, or for documenting groups of people who have been left out of the mainstream historical narrative. In order to capture these oral histories, we have devoted the funds of one of our endowments to support an annual oral history in university history. The “Class of 1931” annual interview about university history is selected through a nomination process. Nominees are selected based on willingness of the nominee to participate, OHC interviewer expertise, uniqueness and rarity of the nominee’s story and level of contribution to campus life, and the generation of the nominee. Since we began this initiative, we have interviewed Laura Nader, Susan Ervin-Tripp, and others.

If you know of an individual who has made an important contribution to the campus (as a staff, faculty, or administrator) and has not been adequately recognized for their work, please consider nominating that person for the “Class of 1931” annual interview in university history. Nominations are due by May 1, 2019.

Martin Meeker

Charles B. Faulhaber Director

Oral History Center

In Memory of Willie C. Gordon

It is with great sadness that we share the news that Willie C. Gordon, lawyer, noir writer, and library supporter, passed away on March 17, 2019. We conducted an oral history interview with him in 2017 and 2018.

Gordon was born and raised in Los Angeles, California and attended college at the University of California, Berkeley. He earned his law degree at the University of California, Hastings College of Law. He worked as a lawyer in San Francisco for many years before becoming a mystery writer. He was the author of six books, including The Chinese Jars, King of the Bottom, and The Halls of Power, among others. He was also an enthusiastic supporter of libraries, and has made significant contributions to the Whittier High Library and to The Bancroft Library for their burgeoning California Detective Fiction Collection. OHC Interviewer Shanna Farrell interviewed Gordon about his early life growing up in Los Angeles, his affinity for libraries, education and career in the Bay Area, and becoming a writer in his retirement.

Nominations Open for Oral History Center’s Class of ’31 Narrators

We are excited to announce that nominations for our Class of ’31 interviews are now open. These interviews are intended to document the life and contributions of a person who has participated in and contributed to UC Berkeley’s campus life.

Selection criteria for nominees include: willingness of the nominee to participate, OHC interviewer expertise, uniqueness and rarity of the nominee’s story and level of contribution to campus life, and the generation of the nominee. Past nominees have included Patricia Pelfrey and Susan Ervin-Tripp.

Nominations are due by May 1, 2019 for the annual “Class of 1931” interviewee; the 2019 interviewee will be announced in mid-May 2019. Direct any questions to Martin Meeker, Oral History Center director: mmeeker@library.berkeley.edu

OHC Director’s Column, March 2019

by Martin Meeker; @MartinDMeeker

How do thoughtful, articulate, quiet people who have something to say get heard? In this day and age in which the loudest voices, the most outlandish ideas, and the most shocking stories get the greatest attention, is there even room for the longform, deep-dive oral histories that the Oral History Center produces? We certainly think that there is — actually, we’re pretty sure that not only is there a place for these interviews, but there is a real need for them. This leaves us with the question: how do we spread word of the remarkable interviews that we conduct? What’s the best way for people who could benefit from our work to learn about it and thus use it?

Since you’re reading this newsletter, you’re already in the loop and engaged with what we do (and we thank you for paying attention!). But we are also constantly examining the ways in which we attempt to connect and considering potential new avenues for outreach. Like most every organization today, we have a pretty robust social media presence. We use our feeds (twitter, facebook, instagram, youtube, and soundcloud) to announce the completion of new oral histories, to pay tribute to narrators who’ve achieved something or sadly passed away, or just to share things reasonably related to oral history which might interest our community. Have you engaged with us on social media? Are you interested in what we have to say? Do you think we might use it better? We want to know.

We try to extend our reach by hosting educational seminars and institutes, by speaking to classes and community groups, and by simply answering our emails (but we get a lot, so apologies in advance if I take a few days to get back to you!). We recognize that a 300-page oral history transcript is sometimes a difficult nut to crack, so we produce brief clips introducing folks to some main themes or interesting moments drawn from the interviews, and share these as widely as possible. We have begun producing podcasts and, soon, longer format videos to show ways in which the original recordings of our interviews can be used to create engaging and informative analytic pieces — and thus encouraging others to use our oral histories in similar ways. And, of course our transcripts continue to provide extraordinarily valuable, irreplaceable evidentiary bases to mountains of books, articles, and theses. What are other options that we might use to spread word of the remarkable interviews? How might the transcripts and recordings be used in novel and enlightening ways?

The big questions posed above are now being addressed head-on by our newly refurbished and expanded production/operations/communications team at the Oral History Center. As a result of a recent search to fulfill our “Communications Specialist III” vacancy, we hired two immensely qualified individuals. David Dunham, who has been on our staff for many years in other capacities, has assumed the new role of Operations Manager; Jill Schlessinger, who came to us from UCB Student Affairs, has joined us as Communications Manager. In addition to working as a team to make sure we continue our successful production of dozens of oral histories every year, Jill and David are tackling these very thorny questions focused on how to raise our collective voice so that the voices of narrators are heard and the content of their oral histories is widely known. Expect to hear more from us in the coming months as all of this comes to fruition. As always, we welcome your input and we’re happy to listen — you might say that’s something we do rather well!

Martin Meeker

Charles B. Faulhaber Director

Meet Jill Schlessinger, the Oral History Center’s New Communications Manager

The Oral History Center is pleased to announce our newest staff member, Jill Schlessigner. She joins our team as Communications Manager. We caught up with her recently to chat about her background in history, interest in oral history, and the projects that she’s most excited to embark on with the OHC.

Q: When did you first encounter oral history?

Schlessinger: As an undergraduate at UC Berkeley, I chose a senior thesis research course that was about oral history. I studied the field of oral history interviewing and research methodology and wrote an oral history thesis. I studied female college students’ attitudes towards abortion from the 1950s to 1980s. Interviewing people from different backgrounds and perspectives taught me a lot about the importance of solid preparation, not making assumptions, and keeping an open mind.

Q: You recently joined our team as a Communications Manager. What were you doing before the OHC?

Schlessinger: Before joining the Oral History Center, I was a content strategist in Student Affairs Communications at UC Berkeley. I’ve had the opportunity to work in a number of fields in my career — higher education, health care, human resources, technology — and I find working in education to be especially fulfilling.

Q: You have a PhD from UCB in History. What did you study?

Schlessinger: I studied US History at the turn of the century, with a focus on social history and women’s history. My dissertation, “Such Inhuman Treatment”: Family Violence in the Chicago Middle Class, 1871–1920, was an analysis of changing power dynamics and community intervention in middle-class families. Something interesting I learned was that many Chicago residents, without anywhere else to turn, pressured the local Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals to address cases of child cruelty, and the Society ultimately changed its mission and name. The Illinois Humane Society became a pioneering child-saving organization. This is something that happened in cities across the country, and numerous animal protection agencies also expanded to protect children and other vulnerable people from physical cruelty.

Q: Which of the OHC interviews do you feel the most connection to, either because of your PhD or current interests?

Schlessinger: It’s challenging to choose just one project because the Oral History Center’s interviews touch on so many of our society’s most pressing issues. However, I would say I feel a connection to the interviews from the Rosie the Riveter World War II American Home Front collection. The Rosies are an important part of women’s history, the history of World War II, and our local history here in the East Bay, and I’ve always found their stories inspiring. On a fun note, I helped break the Guinness world record for the most people dressed as Rosie the Riveter in one place! It’s wonderful that the Oral History Center is instrumental in preserving these voices.

Q: What projects are most excited to be working on?

Schlessinger: The team at the Oral History Center produces an enormous amount of important work. There are the oral history interviews, of course, which delve into the thinking of some of California’s — and the world’s — greatest pioneers and influencers. And the podcasts based on these interviews bring to life the experiences of our narrators and the causes they championed. The Center also conducts a number of educational programs, which reach beyond academics to support journalists, public historians, independent scholars, and others to deepen their interviewing and research skills. We also employ a small army of students who help us with video and transcript production, research, communications, and more. Without them, our historians wouldn’t be able to conduct so many interviews, and it’s wonderful that in turn we are also able to give our students meaningful research and work opportunities. I’m excited to develop a communications plan that helps the Oral History Center share all of this marvelous work, so that people are able to take advantage of everything we have to offer.

Q: How do we get in touch with you?

Schlessinger: You can reach me at jill.schlessinger@berkeley.edu. I’d love to hear from anyone who is interested in helping us share the stories of our narrators and the Center.

Oral History Center Leads Introductory Workshop

by Shanna Farrell; @shanna_farrell

When Spring rains shower the Bay Area, saturating the ground and greying the skies, we know it’s time for our annual Introductory Oral History Workshop. On Saturday, March 2nd, as raindrops beat against our stained-glass windows, we welcomed a group of forty to campus, where they they learned the nuts and bolts of doing oral history . They braved the wet weather to join us from all over Northern California , and even as far as North Carolina.

The oral history project topics of attendees varied from burlesque to the Third World Liberation Front, and from the mining industry to environmental conservation. However, we design our introductory seminars to be applicable for everyone. OHC Director Martin Meeker gave an overview of what makes oral history oral history. Paul Burnett and Roger Eardley-Pryor discussed the intricacies of project planning. Amanda Tewes and Shanna Farrell led a discussion on interviewing techniques. Burnett and Meeker shared recording tips and tricks, and Tewes and Todd Holmes shared potential uses of oral history drawing from a cadre of past projects.

The workshop also featured a live interview exercise led by Farrell. One of the workshop participants, Trisha Pritikin, volunteered to be interviewed by Farrell so other attendees could see an oral history unfold in real time. Eardley-Pryor then engaged Farrell, Pritikin, and workshop participants in a group discussion. Attendees shared their observations, asked Farrell about certain lines of questioning , and inquired how Pritikin felt sitting in the “hotseat.”

These workshops always prove inspiring for OHC interviewers, staff, and student supporters because we interact with attendees who share our passion for oral history.

Thanks to all of you who made the workshop so great! And if you missed it this year, we’ll see you next Spring in 2020!

Want more oral history training? Check out our Advanced Oral History Summer Institute. Email Shanna Farrell (sfarrell@library.berkeley.edu) with questions.

Notes from the Field: Videography and New Changes in Oral History

by Todd Holmes

As in so many professions, the evolution of technology continues to add new dynamics to the practice of oral history. Indeed, longtime veterans of the field have witnessed this development firsthand, as audio recorders transformed from the reel-to-reel setups which nearly required an entire tabletop, to digital devices that now can neatly fit in the palm of one’s hand. And with these changes came new dynamics in the interview process. Bulky equipment no longer encumbered the space between interviewer and narrator, nor did concerns about power sources, room size, or running out of tape.

Today, video recording has become standard practice for many in the field of oral history—a technological step that The Oral History Center took almost two decades ago. In some respects, the use of video could be seen as taking a step backwards, reintroducing a few of the same burdens in the interview process that developments in audio had solved. Yet on the other hand, video also opened up new realms of opportunity, enabling one to capture and preserve an interview in its totality and place both an audio and visual recording of the conversation into the historical record. And of course, among the many promising uses of such video recordings is a documentary film.

Conducting interviews that will be used in a documentary, however, again ushers new dynamics into the interview process, dynamics I began to experience firsthand. In 2016, I initiated the Chicana/o Studies Oral History Project which sought to document the experience of the first generation of scholars who founded and shaped the academic discipline over the last half century. This past year, we decided to partner with film makers to put those twenty-five interviews into conversation in a documentary, tentatively titled Chicana/o Studies: The Legacy of a Movement and the Forging of a Discipline. Since joining the OHC, I had video recorded scores of interviews, and thus was no stranger to the practice of framing a pretty good shot. I paid attention to lighting, the triangulation of the camera with myself and narrator, and made sure to avoid the cardinal sin of having something in the background seem like it was sprouting out of the narrator’s head. Yet when the prospect of using these recordings in a film became a reality, I quickly realized that I had a responsibility to take much more time and care in the videography. A “pretty decent shot” was no longer good enough to do justice to both the film and the narrators featured in it. I thus began to more closely select the interview space, one that featured the best possible light and, above all, background. In the past I feared inconveniencing my narrators, often settling for a less optimal video shot because it was easier for them. Yet for the film, I now had to become assertive about the recording space. It was no longer out of the ordinary for me to rearrange a corner of someone’s office or living room, and spend 20 minutes or more staging the background using items from around the room, office, or house. In fact, at times I even brought my own staging materials when needed. At first blush, such procedures could be deemed more hassle than benefit—a sentiment I’m sure a fair share narrators likely held. Yet my answer to looks of “is this really necessary” was to reassure them of my simple aim: This is for a film, and I want you to look your very best.

When thinking of best practices for videography, I believe that simple aim stands at the center: To place the narrator in the very best position to represent themselves. Achieving that goal surely takes more time and care than just simply sitting down and pushing record. It requires being assertive about the recording space, taking the time to properly stage that space, and paying attention to the little details that, more times than not, we would all prefer to sidestep. Yet when done correctly, you will have a finished product that does justice to both the overall project and, most importantly, the narrators featured in it.

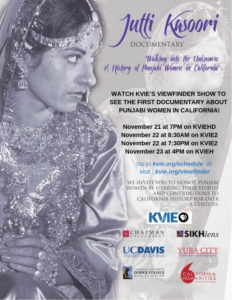

Cal Alum Makes PBS documentary on California’s Punjabi Community

OHC Advanced Oral History Alum Spotlight: A Q&A with Nicole Ranganath

Cal alum Nicole Ranganath’s documentary on California’s Punjabi community recently premiered on PBS. Currently an Assistant Adjunct Professor of Middle East/South Asia Studies at UC Davis, Ranganath joined the Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library at our annual Advanced Oral History Summer Institute in 2015. She was working on a project about women in California’s Punjabi community, and looking to deepen her interviewing skills. Since then, her project grew into a documentary film, Walking into the Unknown, which features 24 life stories of women from this community. We caught up with her to discuss her use of oral history, the film, working with students on the interviews, and why the time was right to do this project.

Q: You joined us in 2015 for the Advanced Oral History Summer Institute. What initially brought you to the Summer Institute?

Raganath: As a Cal alum who worked at Bancroft library as an undergrad, I was already familiar with the great work at the Oral History Center. When I started planning my ambitious project documenting the history of California’s Punjabi community, I found the Summer Institute online and signed up!

Q: You were working on an oral history project about women in California’s Punjabi community. Tell us a little bit about the project.

Raganath: This is the first documentary that focuses exclusively on the untold stories of women in the Punjabi American community of northern California over the last 110 years. Walking into the Unknown features interviews with Punjabi women from diverse backgrounds about their lives, including growing up in India, marriage and family, journeys to the US, and their professional careers. Their extensive contributions to the Punjabi American community and the broader American society have remained invisible. The women also offer compelling eyewitness accounts of major historical events, such as the 1947 Partition, in which over 14 million people were displaced and over one million murdered in religious violence. The project is funded by a grant from the California Humanities, as well as support from UC Davis, Sikhlens and the Punjabi-American community.

What made the project even more poignant is that there was a very narrow window of time in which we could give women a platform for sharing their life experiences. In December 2017, we completed 24 life history interviews on film in Yuba City, Sacramento, Davis, San Francisco, Fremont, and San Jose in just SIX DAYS! Over the last year, the health of three of the elderly ladies was declined so rapidly that they would no longer be able to be interviewed, and sadly one woman passed just away last month.

Q: What did you learn at the Summer Institute that helped you develop the project?

Raganath: The Summer Institute offered a holistic approach to thinking through and planning every aspect of my oral history research. Two aspects of the SI stood out — [OHC Director] Martin Meeker’s help thinking through the agreement process between UC Davis and the partner community organizations, and brainstorming with other participants about their projects. I learned so much from my colleagues.

Q: The project grew into a documentary, Walking Into the Unknown, which features in-depth life stories of 24 women that were interviewed. What was it like to turn these interviews into a film?

Raganath: When I embarked on the oral history research, I didn’t initially intend to create a documentary. With the tremendous support of Sikhlens and the Punjabi community, I got the courage to try to create a documentary film. I’m partnering with the UC History/Social Science Project to integrate the film into K-12 classrooms throughout the state. I encourage other oral history researchers to harness the power of the film medium to share these compelling stories with the general public. I’m very passionate about informing the general public about the Punjabi community’s presence in our state since the 1890s. Most people think South Asians arrived recently in California since the 1970s, but this vibrant community helped build our agriculture, our economy, our railroads, and have contributed to every aspect of our public life. For instance, Dalip Singh Saund was the first Asian American, the first Indian American, and the first Punjabi Sikh to be elected to the US Congress (1956).

Q: How did you adapt the interviews for film?

Raganath: One of the greatest pleasures of this project was creating a summer seminar with 10 students (mostly female Punjabi undergraduates at UC Davis), but also a masters student and a high school student. The students helped translate and transcribe the interviews and within one month they created 800 pages of single-spaced transcriptions of the interviews. We also met each week during the summer to discuss our responses to the often highly emotional interviews with the women. The student feedback greatly influenced my editing process. I was very concerned with capturing the diverse experiences of older pioneer women while also engaging young people to take interest in this history. Editing all of the footage to a short program that is 26 minutes and 43 seconds was not easy! I also greatly benefited from feedback from the other Punjabi women on the planning team who grew up in Yuba City and who were the daughters of some of the pioneer women interviewed in the film — Raji Tumber, Sharon Singh, and Davinder Deol. In short, the editing experience wasn’t easy but the community collaboration and engaging students in the process really helped. The editing team at Sikhlens, especially Hansjeet Duggal, was wonderful to work with as well. The KVIE team also provided invaluable feedback, including Michael Sanford, David Hosley and Alice Yu.

Q: The film premiered at Sikhlens Film Festival in LA in November. What was the reception? Did any of the audience members discuss the use of oral history?

Raganath: The reception at the Sikhlens Film Festival was incredibly positive. Nearly 40 community members, including one of the key pioneer women (Mrs Harbhajan Kaur Takher) attended the premiere. I brought the women involved in the project on stage to honor them. Mrs Takher received a standing ovation.

On November 21, 2018, Walking into the Unknown was broadcast on our local PBS station, KVIE, on their Viewfinder show. You can watch it at kvie.org/viewfinder. The program will rebroadcast on KVIE in April and will be uplinked to other PBS stations nationally later this year. There will be a community screening at the Yuba City Sikh Temple on Sunday, March 17 at 2 pm on Tierra Buena Road. The film will also be screened at the UC Davis South Asia Film Festival on Saturday, May 4 at the International House in Davis. It was very touching to see these courageous women get publicly acknowledged.

Q: What’s next for you? How do you hope to continue using oral history in your work?

Raganath: For this project, I’m finishing part two. We’re in the middle of creating a “women’s gallery” on the existing UC Davis Pioneering Punjabis Digital Archive (pioneeringpunjabis.ucdavis.edu). These women’s stories, including video and audio clips, will be ready by June 2019 for anyone in the world to watch and enjoy. I’m also submitting an article about this project for publication. After that, I’m continuing my oral history work on a book about Sikhs who served in the British colonial administration in Punjab, Fiji, and Africa but then later settled in Yuba City, CA.

William C. Gordon: A Life in Libraries, the Law, and Literary Noir

Image by Ana Portnoy, 2017

We are excited to announce the release of our oral history interview will William C. Gordon, lawyer, noir writer, and library supporter. He was born and raised in Los Angeles, California and attended college at the University of California, Berkeley. He earned his law degree at the University of California, Hastings College of Law. He worked as a lawyer in San Francisco for many years before becoming a mystery writer. He is the author of six books, including The Chinese Jars, King of the Bottom, and The Halls of Power, among others. He is also an enthusiastic supporter of libraries, and has made significant contributions to the Whittier High Library and to The Bancroft Library for their burgeoning California Detective Fiction Collection.

OHC Interviewer Shanna Farrell sat down with Gordon in 2017 to discuss his early life growing up in Los Angeles, his affinity for libraries, education and career in the Bay Area, and becoming a writer in his retirement.