Author: Paul Burnett

From the Oral History Center Director: Oral History, Free Speech & Listening

From the Director: Oral History, Free Speech & Listening

For the past five years, the Oral History Center at UC Berkeley has hosted an annual event in which we honor and express our gratitude to those individuals who donated their time and energy by agreeing to be interviewed. Held every spring, we run this event as a commencement ceremony. We read the names of each narrator whose interview was completed over the year (111 in 2016-2017!), we show video clips from selected interviews, and then we offer our sincere congratulations to the “Oral History Class” of that year. This event has been amazingly successful, each year attracting nearly 100 individuals. Campus friends, community partners, donors, and, of course, our interviewees and often their families too. The event is equally special to the wide range of our interviewees, whether that be a retired Berkeley professor who has spent decades on campus or to a woman who worked in the shipyards in World War II and despite living a few miles from Berkeley had never stepped foot on campus before this event.

This year, in spite of invitations mailed and catering secured, the event almost didn’t happen. As luck would have it, another event was booked for the same night as our event: controversial conservative pundit Ann Coulter was set to speak on campus. Chances are you know what follows because the whole imbroglio became national news, but here’s a brief rundown to serve as a reminder: conservative provocateur Milo Yiannopoulos was invited by Berkeley College Republicans to speak on campus on February 1, 2017. In response to this anticipated speech, protesters assembled and, later in the evening, the protests turned violent when anarchists took over and ran roughshod over the university and nearby downtown Berkeley, vandalizing businesses and causing general mayhem. People were injured and the university and city suffered fairly widespread (and expensive) property damage. And Milo was prevented from speaking. The College Republicans, frustrated and humiliated by the events of February 1st, doubled-down and invited Ann Coulter to speak. In the weeks and days before her scheduled appearance, rhetoric from all sides flared, initially sparked by anarchists who vowed to use violent tactics to prevent her from speaking. We waited until the last minute, hoping that cooler heads would prevail, but a few days before the event was to take place the university police recommended that we cancel, suggesting that they couldn’t guarantee security to our staff or our attendees — which spooked us a great deal considering that many of those expected to attend were elderly and unfamiliar with the campus.

I personally found the whole set of events depressing, even disturbing, and I began to think about the relationship between free speech and the power of listening, of hearing — and, thus, of the relationship of each to what we practice in our office: oral history. And while this audience needs no definition of oral history, I think it worth mentioning that all of our interviews are preceded by extensive research, the interviews are recorded on digital video and transcribed in their entirety so that interviewees are given the opportunity to review and approve their interviews prior to their release to the public. That is, in a nutshell, how we practice listening, hearing… oral history.

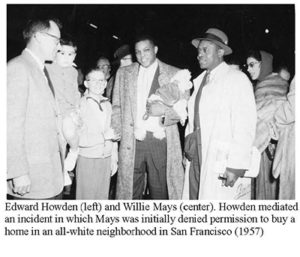

Within a few weeks, we decided to reschedule the event (it was held on June 22nd), and it went off without a hitch! We expected about 60 people to show, but more than 90 people attended, including 98-year old Ed Howden, a legendary civil rights pioneer who staged free speech gatherings on the Berkeley campus when he was a student — in 1940! What follows are the remarks that I prepared for that event and I hope that you find them to be of interest and perhaps inspire you to recognize the importance of the work we do as oral historians in this day and age.

*****

I want to welcome everyone to the Oral History Class of 2017 Commencement Celebration — the fifth annual hosting of this very special event! As you probably know, we needed to reschedule from April because of the anticipated appearance of a controversial speaker on campus, and the threat of violent response by groups of individuals who wanted to prevent that speaker from appearing.

Our event was a casualty of the moment, but one might say that free speech was a casualty too — which is a difficult scenario to watch for someone who relishes in the fact that this university was the birthplace of the Free Speech Movement just over 50 years ago! But, you can breathe a sigh of relief: I’m not going to lecture about that speaker or those who were opposed to her this evening. But I do want to begin this event with a few thoughts about the integral connections between free speech and oral history.

The First Amendment to our Constitution guarantees that “Congress shall make no law … abridging the freedom of speech …” and this has been widely understood to mean that as a people we are granted the right to speak our minds, to pronounce our opinions (popular or unpopular), and even to say things that others might deem obscene or distasteful, so long as these words do not incite violence. As such, our doctrine of free speech is absolutely necessary for the successful practice of oral history — for the practice of recording subjective memories of times past and often opinionated interpretations of the impact of the past on our lives today. Not the interviewer or anyone else can guarantee the right to our narrators to speak freely for that right is granted to them by our most fundamental laws.

Quite happily, our narrators freely invoke their rights and convey stories both mundane and profound, political opinions widely shared and deeply unpopular, accounts of events that hew closely to previously-accepted versions and recollections that depart wildly from what we think we know. As an interviewer, I appreciate — indeed, cherish — everything that comes out in an interview and am always gratified that even in this day and age of perpetual scrutiny of what we say, people still feel a great deal of freedom to speak their minds and share their innermost thoughts. This, I think, is a true strength and contribution of oral history: the creation of a venue for the exercise of the freedom of speech

But there is another element here that I most want to emphasize today — something that is just as necessary and perhaps even more powerful than free speech itself. This is something that we might see as the verso of free speech and this is the call to listen so that all this speech might actually be heard. Indeed, one might argue that we live in a world with too much speech, not nearly enough listening. I think that people tend to speak more loudly and say things that are more extreme not necessarily because they hold true to those beliefs closely but because they feel like they are just not being heard in the first place.

This is where the unrecognized transformative power and importance of oral history resides: oral historians have spent decades (well, millennia if you go back to Herodotus and Thucydides) perfecting the art, the craft, the scholarly methodology of interviewing, of listening, of actually hearing what our narrators are saying. The good oral historian is not merely a passive sounding board, quietly nodding while making sure the recording equipment is working. Instead, the good oral historian listens deeply to what our narrator is saying, simultaneously comparing it to what we’ve heard others say, and then asks follow-up questions seeking clarification, new information, confirmation or disputation of interpretations. In this way, good oral historians communicate to their narrators that they are being heard, that their ideas are being wrestled with, that their version of events … matters!

By being truly heard in this fashion, our narrators don’t typically feel the need to shout, to defame, to become frustrated. Instead, they rise to the occasion and present their stories almost always in thoughtful and in-depth sentences often replete with new insights. Human discourse is elevated in these settings and, well, I think that we are all better for it. Thus, in oral history we discover not only a place in which the freedom of speech is beautifully enacted, but just as importantly, a place in which the person who goes to the trouble of giving their point of view actually feels heard. And, I want to point out that none of this could be actualized without the thoughtful and engaged work done by our staff of interviewers, editors, and technologists or the generous contributions of you, our interviewees.

This is why I’m so proud of the work that we do at the Oral History Center. This is a unique and valuable place in which we solicit, value, and hear stories from people across all walks of life: people who come to us from different economic, education, racial, ethnic, gender, religious, ideological, and political backgrounds and beliefs. In the class of 2017, our interviewees ranged in age from 27 to 98; they were born in the US and abroad and live in states from New York to Oklahoma to California; they are CEOs and social activists; attorneys and welders; former Fire Chiefs and pioneering linguists; they are Republicans, Democrats, independents or their political affiliation is simply unknown to us. I should add that this profound diversity of narrators demonstrates that Berkeley’s Oral History Center does not discriminate by recording interviews only with those whom we view as heroic or as validating beliefs that we hold personally — we seek to interview and to listen to as many varied individuals as possible. We value all voices and we treat each interviewee the same: we endeavor to truly hear what they — what you — have to say.

Martin Meeker

Charles B. Faulhaber Director

Oral History Center at UC Berkeley

June 2017

Highlights from the Oral History Class of 2017!

Conservation and Craftsmanship: Brian Considine, Senior Conservator of Decorative Arts & Architecture at The J. Paul Getty Museum

As a mere museum-goer I have often longed to touch one of the beautiful artworks on display only to be stayed by a watchful security guard or cordoned off to my appropriate space by a prohibitive velvet rope. It’s in that very moment that a set of questions emerge. Who gets to know these objects on a more intimate scale? Whose hands actually get to touch these works of art? The answer to both these questions is resoundingly the museum’s conservator.

In continuation of the Oral History Center’s ongoing collaboration with The Getty Trust we are pleased to release our interview with the J. Paul Getty Museum’s longtime Senior Conservator of Decorative Arts and Sculpture, Brian Considine.

Considine recently retired from the Getty Museum, but his legacy lives on. In his over twenty years of service, Considine oversaw the creation of the museum’s decorative arts conservation laboratory, consulted on the preservation of King Tut’s tomb in Egypt, ensured the structural integrity of the museum’s many textiles, sculptures and 18th French cabinets, and managed the installation of the Getty Museum’s historical panel rooms.

A furniture maker with professional training in gilding and marquetry, Considine is an expert in the connoisseurship and conservation of 18th century French furniture and decorative arts. In other words, it’s his hands that have gilded countless furniture items from Louis XIV’s reign and felt for the rough unfinished bottoms of authentic period pieces. Conservation and craftsmanship are, after all, incredibly tactile practices.

Drawing from his experience as a furniture maker, Considine describes how he engages with furniture objects:

“You touch it. You rub it. The feel of the wood on the palm of your hand is so important. Any furniture maker will tell you—. Except like Knoll or something. But I mean any hand furniture maker will tell you that rubbing it is just so important. And the smell. The smell is a combination of the wood and the finish, but—. If the finish is a really nasty synthetic lacquer or something, it’s got this sharp, biting smell. Whereas if it’s linseed oil and wax, which is what I used, it’s got this soft, natural, rich smell.”

Considine’s interview is an important addition and resource for anyone interested in 18th century French furniture, the shifting practices of arts conservation, and the larger importance of preserving material culture from around the world. We invite you to watch the following excerpt with Considine talking about the J. Paul Getty Museum’s Ledoux panel room and read his complete oral history at the OHC website.

New Release: Robert Irwin with Jim Duggan on the Getty Central Garden

We are thrilled to release our latest interview in partnership with the Getty Trust: the artist Robert Irwin on his Central Garden for the Getty Museum. Joining Irwin for the second interview session was Jim Duggan, the master gardener who facilitated Irwin’s vision for a garden that has become a living, breathing, evolving piece of sculpture — not to mention one of the most visited and popular pieces of art at the museum.

Robert Irwin was born in Long Beach, California, in 1928. As a young man, he worked as a lifeguard and professional swing dancer while creating his early paintings. In the 1950s, he became a pioneer of the “Light and Space” movement popular with a handful of now very influential southern California artists. Later in the 1960s and 1970s he moved away from painting and developed what he called “conditional art,” or art that was created in direct response to various physical, experiential, and situation conditions. In the early 1990s, he was brought in by the Getty Trust to design the new Getty Museum’s garden. Although the museum’s architect, Richard Meier, was not a fan of Irwin’s imaginative creation, the Getty Central Garden has proved to be extremely popular with visitors and is now regarded as a masterpiece of landscape art.

New Release: Cantor Roslyn Jhunever Barak

In partnership with independent interviewer Basya Petnick, the Oral History Center is pleased to make available her interview with renowned Cantor Roslyn Jhunever Barak. By way of introduction to this remarkable interview, we have reprinted excerpts from Ms. Petnick’s interview history below.

An interview history is a little piece of meta-historiography—a history of a history—intended to help the reader understand the interviews more completely. Typically, this piece discloses the purpose of the interviews, the relationship between the participants, and any special circumstances that developed during the interviewing, transcription, and editing processes.

Twenty-five years ago I came to the field of oral history from the worlds of literature, journalism, and creative writing, along with a lifelong interest in religious and spiritual matters. No doubt these interests affected the questions I asked and did not ask in the interviews. Mostly, however, my attention was focused on the task that oral history does so well, and that is to add to the existing record of a subject area, either through topical interviews with a number of people, or through the lens of one person’s full-life history…

Relationship

Like an ethnographer, the oral historian “occupies a position of structural location and observes with a particular angle of vision.” Age, gender, race, insider/outsider position, social status, and other factors are well known to affect the conduct and outcomes of oral history interviews.

Prior to the start of this project, I knew Cantor Barak only in a formal way, as “my cantor,” the senior cantor of Congregation Emanu-El in San Francisco, where I had been a member for twenty years.

We had at once no prior relationship and yet at the same time an extremely important relationship. Hers was the voice that called me to prayer on Shabbat morning and evening and on the High Days. Hers was the voice that chanted the Kaddish for my family members on their yahrzeit year after year; hers was the voice by the bed and gravesides of ill and grief-stricken friends. Hers was the voice on my anshei mitzvah (adult bat mitzvah) study tapes from which I learned the prayers and blessings and, of course, my Torah portion: I knew well Cantor Barak’s every breath and phrasing of our basic Reform Jewish liturgy, which I had learned not just for my ansheit mitzvah but for a lifetime. Her prayers literally had become my prayers and, without specifically intending it, we had entered into a unique relationship that only a cantor/teacher and congregant/student may have: that of praying the liturgy together syllable-by-syllable, breath-by-breath. I was in awe of her vocal ability and had great respect for her as a senior member of the Emanu-El clergy, but because of her congenial personality I felt at home and comfortable with her during the interviews and enjoyed talking together in our profession roles of oral historian and cantor.

Over the years, I had attended many services led by Cantor Barak, and while seated in one or another of Emanu-El’s three sanctuaries, I watched the world around her change. As the decades passed, the popularity of organs, choirs, complex music, and a cantor-dominated service declined, while the contemporary, guitar-led, arms-around-my-neighbor, clapping and communal singing of all the prayers by everyone gained popularity and momentum. In time it became clear that camp-style participatory singing was a fait accompli. Naturally I did what all oral historians must do: take digital recorder in hand, research and write questions, and begin to document significant change.

In the spring of 2013, I invited Cantor to discuss the prospect of recording her oral history. During our luncheon, I talked with her about why I thought her oral history would be valuable to researchers, congregants, Jewish music enthusiasts, and other cantors now and in the years to come. She seemed comfortable with the idea of being interviewed extensively; she asked key questions and attentively listened to responses.

Interviewing

To interview Cantor Barak repeatedly is to be included in the soft whirl of friendly chaos that gently surrounds her life. In her world, there is always someone coming in or going out, someone calling on the house phone or cell phone, or someone at the door. There may be an old New York friend or a temple in Texas calling, but regardless, all Barak household activities are punctuated by barking, or by someone telling the dog to please stop barking. And there are always dogs. In the course of about a year—the time it took to complete the twelve interviews—Figaro, a disturbed Jack Russell terrier mix, and a psycho poodle named Elmo came and went, until finally, Schatzy, a little schnauzer, came to stay.

There was a continual stream of repairs and repairmen that joined our quiet time together. First it was a serious water leak, and then something that involved the garage, and then a crew with chain saws arrived to limb the trees right outside her house. At some point, jackhammers became included in the interviews, as well as tree branches of varying sizes, and pieces of the neighbors’ concrete that had to be removed in an enormous truck with the loudest backup warning sounds I have ever heard. During the interviews, there were instructions to be given, cautions to be issued, and dog walkers and friends to be greeted. There were potential renters and their agents to see the house before Cantor’s impending temporary move to Dallas. There were doorbells ringing and someone stopping by for just a minute. There was often something lost … often something that is “here … someplace.” There was David Olick, her partner, a lawyer working at home. There were iPads and iPhones and a 50” TV screen and laughter and apologies for all of it, and generous offerings of fruit and tea and other lovely gifts. If all this were happening in my quiet, almost monastic life, I might go nuts, but at Cantor’s, I enjoyed it. To her it was normal, and it became normal to me, too. I especially enjoyed her dogs and missed them when they were returned to the dog rescue because they were quirky and refused to be trained.

A curious thing about the interviews I conducted in her home is that she didn’t face me. During the recording sessions, she would sit in her leather recliner, stare into space and talk, while I sat on a nearby couch to the side of her. This meant that no nonverbal clues were possible: I couldn’t see her face and she couldn’t see mine. I couldn’t see her eyes to know the effects of my questions or learn if there were any disconnects between her facial expression and her verbal responses. Further, to redirect the flow of her narrative from that position required that I make a serious verbal incursion into the swift tide of thoughts and memories that formed her responses. I did not try to change this arrangement, however, because she seemed so utterly comfortable with it, and I deeply knew that the interviews would be more fruitful if she were completely comfortable. I report this simply as a description of “what the body did” during the interviews; it goes to the somatic side of the story, the part the reader cannot see.

To continue recounting factors that influenced the interviews: we are both Jews, and therefore, an important influence in our interviews was the prohibition in Jewish life against lashon hara, which might be understood as harmful speech. More than just avoiding gossip, this practice requires not speaking in a harmful way on any occasion. But talking and not talking about people is tricky, because from the start, one’s life is full of people—we cannot even live without being connected to people—but, when mindful of lashon hara, there is often little that can be said about others, as much as we might like to say more. It’s similar to how we use or do not use humor: one wants to tell a joke because it expresses a truth and seems funny, but it might be hurtful to in-laws or the elderly or a certain ethnic group, so we don’t do it: on a good day we resist the impulse.

Another inhibition that slightly constrained the interviews was the “gag order” that had been imposed on Emanu-El clergy by their board of directors during the days when Rabbi Robert Kirschner was stepping down from his position as senior rabbi. While Cantor Barak was deeply affected by his demise, she spoke cautiously about that incident, and I did not probe for more.

Also missing from the interviews are questions about what is like to be a female cantor. Not many women like to be asked what it is like to be a female this or a female that. The question can be unintentionally diminishing, and I could not bring myself to ask it. I had learned at the outset of my research that soon after Cantor Barak began her training at Hebrew Union College, the program filled with female cantorial candidates. As it has been said, “Female cantors are so ubiquitous now that some people are even surprised to see males in the role!” I also knew that during her many years at Emanu-El, she had served on a staff of clergy that included several female rabbis, a female lay cantorial singer, and strong women on the board of a temple where women are notably powerful and gender not a major issue. Of course, it was not always this way. Long before women were invested as cantors, Julie Rosewald, a lay cantorial soloist with a beautiful, classically trained voice, led the prayers and directed the music at Congregation Emanu-El for nine years. Sadly, she has been left out of important histories written about Emanu-El and is not included in the photo history posted on the wall outside of two of the three sanctuaries. From the start, Cantor Barak reminded me to be sure to include Julie Rosewald in this oral history; subsequently, we discussed Rosewald’s contribution in the interviews below.

What I wanted to know and could not find out through either my interviews or research is: what is the effect on the hearer of the female voice as opposed to the male voice? What is the difference in the impact of the sound of the liturgy sung by a female in the soprano/alto range from the impact of the liturgy sung in the male tenor/baritone range? This question is difficult both to formulate and to answer.

Bill Clemens / UC Museum of Paleontology Oral History Project

The Bill Clemens / UCMP oral history project has been several years in the making. Historian Sam Redman first proposed to do a history of members of the University of California Museum of Paleontology in 2011, specifically to interview Dr. William Clemens and a number of his graduate students. The concept behind the project was novel and important: to document with long-form oral history of successive cohorts of students who were advised by a single scholar, while at the same time interviewing the scholar in depth about the evolution of his field, as well as the key transformations in the institutions in which he played significant roles.

UCMP Associate Director Mark Goodwin was the fulcrum in organizing the project, from fundraising to arranging for interviews with Bill’s students from all over the world. My first session with Bill was December 18, 2014, and my last was March 10, 2016. One of the factors contributing to the length of time spanning these sessions was the fact that Bill was caring for his wife Dorothy “Dot” Clemens while she battled cancer. There was some hope that she would live to see the project completed, but she ultimately passed before its completion. After a time, Bill resumed the project, in tribute not only to UCMP, his colleagues, and students, but also to her memory, as Dorothy Clemens was deeply committed to ensuring that Bill’s oral history was documented for the ages.

Several themes are explored in his interview. There is a longstanding concern in the history of science with the ways in which scientists establish and maintain their credibility within and beyond their communities. By the 1950s, the queen of the sciences was physics, and the public was consumed by the promise and peril of high technology, from the splitting of the atom to the electronic consumer items in the shops. In the public mind, paleontology perhaps had more in common with the 19th-century field sciences than with the burgeoning domains of digital computing or molecular biology.

When Bill Clemens started his undergraduate work UC Berkeley Department of Paleontology at the beginning of the 1950s, the modern evolutionary synthesis in biology, which linked laboratory research in genetics to field studies, statistical analysis, paleontology, and a revitalized Darwinian theory of evolution, had only just been worked out before the war. The helical structure of DNA was announced in Bill’s junior year. In other words, Bill began his career at the beginning of a new common cause in science — a better understanding of relationships between genetic variation and distribution in changing environments over geologic time — with cascades of new questions to follow in the decades to come.

This project allows us to look at how the synthesis unfolds in the 20th century in terms of relationships among and across disciplines, the deployment of new techniques and technologies, and in terms of the social and historical context of scientific knowledge production.

Front: Mark Goodwin, Cathy Engdahl, Mike Greenwald, Lowell Dingus

Rear: Jane, Bob, and Duane Engdahl (Skinner Award honorees), Bill, Dave Archibald

Photograph courtesy of Mark Goodwin

The drama of paleontology is often heightened by the public and romantic interest in the gigantic specimens. Owing in part to the Evolutionary Synthesis, the paleontologists of Bill’s cohort were interested, not just in the structures of fossil specimens themselves, but in where and how they lived in relation to one another. To get at some of these ecological questions, these students turned for example to the very small microvertebrates which could be found with a new technique of screenwashing, basically sifting for tiny fossils. What they found in the Lance Formation in Wyoming in one season equaled the number of fossils of their kind ever discovered up to that point. The field branched away from the romance of the big dinosaurs and toward a more detailed understanding of evolutionary relationships among specimens and of the developmental characteristics that might tell the scientists something about how the creatures lived.

There is a lot of research in the history of science devoted to what historian of science Rob Kohler called the lab/field border. The basic question is this: given the growing disparity in prestige and resources between the field sciences and the bench sciences in the early 20th century, how did field scientists struggle for recognition, authority, and scarce resources, when the best scientific practice was increasingly defined as the controlled laboratory experiment?

Field scientists brought techniques and instrumentation into the field to increase the precision and quantity of data collected; and they also brought back from the field new questions to lab scientists and theorists about the complexity, messiness, and porosity of the data. This project shows that this process is part of the ongoing fulfillment of the evolutionary synthesis: a harmonization of the basic questions across the life sciences, with the kind of cross-fertilization that we saw in Charles Darwin’s education and work practice. We see new hybrids of paleontology and other life sciences emerging, such that some practitioners could be viewed from a distance as statisticians, or labcoat-wearing experimentalists working with the vast collections of specimens collected by Bill and others. The other piece of the lab/field border concept is that the field is also a complex social and political place. This is one of many of Bill’s soft skills that students talk about over and again in the history. How does one maintain good relationships with the property owners who are stewards of the places in which the paleontologists work?

For all of these reasons and more, place is important in the field sciences. But in few sciences is the precise meaning of place as important as paleontology, where a few feet of geological strata contain millions of years of data. Here is Bill Clemens on the trickiness of pinning down a fossil to a place, and therefore a time.

It’s important not to understate the importance of this scale and extent of fossil collection. The organized work of Clemens’ generation and the one that followed made possible newer types of data-intensive computerized research on paleontology, evolutionary biology, and climate change.

Here is Marisol Montellano on the importance of Bill’s efforts in fossil collection and characterization.

In fact, it is not uncommon for doctoral students today to conduct their research entirely with collected specimens in a laboratory, although Bill might not recommend this exclusive a course of study.

Here is Bill’s last student, Greg Wilson, on what Bill was like as teacher and a mentor.

Bill Clemens’ Students

It is here that we come to a really special aspect of this history, the second volume of this project: the thirteen interviews with Bill’s graduate students and the current Curator and leader of the UC Museum of Paleontology, Charles Marshall. Bill and his students are witnesses to the changes in the field of paleontology, the increasing use of computing to process large quantities of data, and the field’s increasing involvement in the most pressing questions of the last four decades: the resilience of species, the interdependence of organisms, and the consequences of a changing climate on the abilities of organisms to adapt to both sudden and gradual changes. Here is Bill’s former student Jessica Theodor on Reconciling Molecular and Morphological Data.

These questions are also a reflection of my initial theme about credibility in science. Through these interviews, we see how paleontology has adapted itself to a changing scientific climate, contending with the introduction of new species of ideas such as the asteroid-impact hypothesis for the extinction of most dinosaur species at the end of the Cretaceous, or through the adoption of sophisticated mathematical analyses of the surface structure of mammalian teeth to answer questions about the evolution of a particular species’ diet millions of years ago.

Here is Lowell Dingus on how he dealt with the approach of physicists Walter and Luis Alvarez to the question of the extinction of many species at the end of the Cretaceous Period.

Scientists struggle for credibility, and one way of doing so is to hybridize their research techniques and programs with the dominant sciences of the day, such as molecular and structural biology. The Department of Paleontology’s integration with the Department of Integrative Biology at UC Berkeley was part of a larger effort to cross-fertilize ideas and techniques from related disciplines that focus on evolutionary processes. “Interdisciplinarity” had an early home here at Berkeley and especially at UCMP, long before Integrative Biology was founded in the 1990s. One result of this integration is that the UC Museum of Paleontology has once again assumed a worldwide leadership role in the conduct of cutting-edge research, though it has long led the field of mammalian paleontology.

On a more human level, you will find in these pages, that the engines of research and innovation are fueled by human virtues as much as intellect. Bill and Dot’s patience and empathy for Bill’s students as they navigated the challenges of graduate school and the dust and heat of the field is well documented, as is Bill’s curiosity, meticulousness, patience and care with which he draws his scientific conclusions. It is surely a mark of his influence that his students have taken up the charge by using new techniques evidence, carefully tested, to gradually move their respective fields forward increment by increment.

Paul Burnett

Berkeley, CA, 2017

New Release: Edward Howden, California Civil Rights Advocate

Today we release a very special oral history interview: Edward Howden, a pioneering advocate for civil rights and social justice in community-based organizations and early governmental civil rights institutions. Howden, who attended UC Berkeley from 1936 to 1940, was 98 years when we completed his interview earlier this year. To introduce this oral history, we’ve reprinted the interview’s “Foreword” by San Francisco State University Professor Emeritus of History Bob Cherny:

“Today San Francisco and, perhaps with some exceptions, California have reputations for diversity and for inclusion without regard to ethnicity, religion, or gender. California was the first state to elect women to both of its U.S. Senate seats. Currently, the speaker of the state Assembly and the president pro tempore of the Senate are both Latinos. The Chief Justice of the California Supreme Court is a Filipina American. The last six mayors of San Francisco have included a woman, an African American (in a city where African Americans make up less than eight percent of the population), and a Chinese American. Many similar examples could be cited.

One might be tempted to conclude that this level of political inclusion has arisen naturally from a diverse population, but there are other parts of the country where diversity has not automatically brought inclusion. A study by sociologists in 1970 suggested that San Francisco had a “culture of civility” based on tolerance for what they called, in the sociological jargon of that time, “deviants.” However, their explanation for this tolerance is unconvincing, focusing on an alleged “Latin heritage,” a “libertarian and politically sophisticated” working class, and a high proportion of unmarried adults.

Such an analysis leaves out a great deal, both in understanding the development of widespread tolerance of difference, and such tolerance does not automatically lead to inclusion into the social, economic, or political mainstream. There is a difference between tolerating difference and celebrating diversity, and neither itself produces inclusion. Inclusion of diverse groups and individuals into the mainstream has resulted from long-term struggles against both outright racism and more subtle forms of discrimination. In recent decades, historical scholarship has often focused on the ways that various groups have organized themselves to seek equality and inclusion.

The history of efforts to create a more inclusive society involves more than the efforts of excluded groups to organize themselves and demand inclusion. Equally important have been the historical battles that reformers—not themselves members of a discriminated against group— have waged against outright racism and more subtle forms of discrimination and in favor of inclusion. This oral history provides essential documentation to this aspect of the history of California. Throughout his professional lifetime, Ed Howden promoted such goals by campaigning for what he prefers to call human rights: first, in advocating that San Franciscans become more inclusive, then in using the authority of the State of California to bring greater inclusion in employment, and finally as a mediator, seeking to resolve community problems over rights.

I first met Ed at Alma Via, an assisted-living facility where my mother was a resident. Ed often sat at her table during breakfast, and we got to know each other over that breakfast table. I had known a bit about Ed’s work through my research and writing about California history and politics in the mid- to late 20th century. Meeting him in person over breakfast jogged my memory about some parts of his history and reading this oral history has told me a great deal more.

As you will discover from this account, Ed was involved throughout his long career in the struggle for what he defines as human rights. In the pages that follow, he relates how some of his experiences as a student at the University of California, Berkeley, in the 1930s and in the army during World War II led him in 1946 to accept the position of director of the Council for Civic Unity (CCU). Prominent members of San Francisco’s Catholic, Jewish, Protestant, and African American communities had established the CCU, and, as director, Ed worked to develop an awareness of discrimination and to advocate solutions. He utilized public meetings at the Commonwealth Club, radio and later television programs, the city’s four daily newspapers, presentations to the Board of Supervisors, and individual contact with the city’s movers and shakers. He was centrally involved behind the scenes in 1957 in the resolution of the imbroglio over the attempt by Willie Mays, a star player on the recently arrived San Francisco Giants, to buy a house in an all-white neighborhood. Ed also took the lead in writing and publishing A Civil Rights Inventory of San Francisco (1958) that detailed discriminatory employment and housing practices.

In 1959, Ed moved from what would today be called an advocacy organization, the CCU, to a governmental position. The year before, in 1958, Edmund G. “Pat” Brown, who had been the California Attorney General and before that the San Francisco District Attorney, was elected governor. As governor, Brown worked with the Democratic leadership in the legislature to create the state Fair Employment Practices Commission (FEPC). Brown appointed Ed as the first director of that agency, and Ed remained in that position for more than seven years, until Ronald Reagan became governor. After leaving the FEPC, in early 1967, he joined the Community Relations Service, a federal agency established within the Department of Justice under the Civil Rights Act of 1964. He began western regional director and then became a Senior Conciliation Specialist. He retired in 1986. In that agency, he sought to mediate community problems involving human rights. Much of his work in that agency is covered in a separate oral history, done in 1999, but in this oral history Ed reflects on his central involvement in bringing a peaceful resolution to the 1973 stand-off at Wounded Knee between the FBI and American Indian Movement activists.

Ed’s story is that of one who has worked tirelessly, sometimes prominently but often behind the scenes, to eliminate practices that discriminated on the basis of race and thereby to promote inclusion. At the center of his work stands his belief that respect for human rights is the basis for decent relations among all the groups that make up a diverse society.”

New Release: Wayne Feinstein, Former Executive Director, Jewish Community Federation of San Francisco, the Peninsula, Marin and Sonoma Counties, 1991-2000

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library is pleased to announce the release of a new life history interview with Wayne Feinstein, who served as Executive Director of the Jewish Community Federation of San Francisco, the Peninsula, Marin and Sonoma Counties from 1991 to 2000.

Wayne Feinstein was born Albany, New York, in 1952 and raised largely in Columbus, Ohio. He was active in his local Jewish congregation as a teenager and seriously considered the idea of attending seminary. He took an undergraduate degree from Colgate College and after graduation went to work for a series of Jewish community nonprofits, including: the United Jewish Appeal, the Jewish Welfare Federation in San Francisco, and the Council of Jewish Federations in New York. His first leadership role was as executive director of the Jewish Federation of Metropolitan Detroit, which was followed by years heading up the Los Angeles Jewish Federation and the San Francisco Jewish Community Federation, where he was executive director from 1991 to 2000. In 2000, he switched careers, going into the private sector, eventually becoming a vice president at the Capital Group. In this interview, Feinstein discusses his childhood, education, and experiences formative in the development of his decision to serve the Jewish community for roughly three decades. He surveys the landscape of Jewish communal organizations and describes how the roles played by those organizations changed over the last quarter of the 20th century. Feinstein details, in particular, the three federations for which he served as staff executive, focusing on the fundraising and service functions of those organizations.

Mr. Feinstein’s interview adds yet another voice to our long-running interest in documenting Jewish philanthropy and community life in the San Francisco Bay Area, particularly through our “Jewish Community Leaders” oral history project. Other significant interviews from that project include: Annette Dobbs; Peter Haas, Samuel Ladar; William Lowenberg; Brian Lurie; Roselyn Swig; and many more.

Freedom to Marry Oral History Project

The Freedom to Marry Oral History Project

In the historically swift span of roughly twenty years, support for the freedom to marry for same-sex couples went from an idea a small portion of Americans agreed with to a cause supported by virtually all segments of the population. In 1996, when Gallup conducted its first poll on the question, a seemingly insurmountable 68% of Americans opposed the extension of marriage rights. In a historic reversal, fewer than twenty years later several polls found that over 60% of Americans had come to support the freedom to marry nationwide. The rapid increase in support mirrored the progress in securing the right to marry coast to coast. Before 2004, no state issued marriage licenses to same-sex couples. By spring 2015, thirty-seven states affirmed the freedom to marry for same-sex couples, with a number of states extending marriage through votes in state legislatures or at the ballot box. The discriminatory federal Defense of Marriage Act, passed in 1996, denied legally married same-sex couples the federal protections and responsibilities afforded married different-sex couples—a double-standard corrected when a core portion of the act was overturned by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2013 in United States v. Windsor. The full national resolution came in June 2015 when, in Obergefell v. Hodges, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the Constitution’s guarantee of the fundamental right to marry applies equally to same-sex couples.

The Oral History Center is thrilled to release to the public the first major oral history project documenting the vast shift in public opinion about marriage, the consequential reconsideration of our nation’s laws governing marriage, and the actions of individuals and organizations largely responsible for these changes. The Freedom to Marry Oral History Project produced 23 interviews totaling nearly 100 hours of recordings. Interviewees include: Evan Wolfson, founder of Freedom to Marry; Kate Kendell, executive director of the National Center for Lesbian Rights; James Esseks, director of the ACLU’s LGBT & HIV project; and Thalia Zepatos, the movement’s “message guru” who worked at Freedom to Marry as director of research and messaging. Read on for video clips of the interviews and links to complete interview transcripts.

At the center of the effort to change hearts and minds, prevail in the courts and legislatures, win at the ballot, and win at the Supreme Court was Freedom to Marry, the national campaign launched by Harvard-trained attorney Evan Wolfson in 2003. Freedom to Marry’s national strategy focused from the beginning on setting the stage for a nationwide victory at the Supreme Court. Working with national and state organizations and allied individuals and organizations, Freedom to Marry succeeded in building a critical mass of states where same-sex couples could marry and a critical mass of public support in favor of the freedom to marry. This oral history project focuses on the pivotal role played by Freedom to Marry and their closest state and national organizational partners, as they drove the winning strategy and inspired, grew, and leveraged the work of a multitudinous movement.

Freedom to Marry Oral History Project Interview Transcripts:

Barbara Cox, “Barbara Cox on Marriage Law and the Governance of Freedom to Marry.”

Michael Crawford, “Michael Crawford on the Digital Campaign at Freedom to Marry.”

Scott Davenport, “Scott Davenport on Administration and Operations at Freedom to Marry.”

Jo Deutsch, “Jo Deutsch and the Federal Campaign.”

Sean Eldridge, “Sean Eldridge on Politics, Communications, and the Freedom to Marry.”

James Esseks, “James Esseks on the Legal Strategy, the ACLU, and LGBT Legal Organizations.”

Harry Knox, “Harry Knox on the Early Years of Freedom to Marry.”

Matt McTighe, “Matt McTighe on the Marriage Campaigns in Massachusetts and Maine.”

Amy Mello, “Amy Mello and Field Organizing in Freedom to Marry.” (forthcoming)

John Newsome, “John Newsome on And Marriage for All.”

Kevin Nix, “Kevin Nix on Media and Public Relations in the Freedom to Marry Movement.”

Bill Smith, “Bill Smith on Political Operations in the Fight to Win the Freedom to Marry.”

Marc Solomon, “Marc Solomon on Politics and Political Organizing in the Freedom to Marry Movement.” (forthcoming)

Tim Sweeney, “Tim Sweeney on Foundations and the Freedom to Marry Movement.”

Cameron Tolle, “Cameron Tolle on the Digital Campaign at Freedom to Marry.”

Thomas Wheatley, “Thomas Wheatley on Field Organizing with Freedom to Marry.”

Evan Wolfson, “Evan Wolfson on the Leadership of the Freedom to Marry Movement.”

Thalia Zepatos, “Thalia Zepatos on Research and Messaging in Freedom to Marry.”

Spring Oral History Workshop

We are thrilled to continue to offer our expanded educational programs through our one-day introductory workshop. On February 25, 2017, the OHC hosted our third annual Spring Workshop at the MLK Student Union. Designed for anyone interested in learning more about how to bring oral history to their work, the workshop provides participants with the tools to plan their own oral history projects, conduct and record interviews and preserve and share their interviews. This year, our Spring Workshop participants included independent researchers, journalists, representatives from the California Association of Highway Patrolmen, undergraduate and graduate students, genealogists, and professors from across the United States.

The OHC staff led the day’s various sessions, which mirrored the cycle of an oral history project. Martin Meeker started the day with an overview of oral history and was followed by Paul Burnett on project planning and Shanna Farrell’s incisive dissection of the interview process. The day also included a session by David Dunham on recording techniques and a new presentation by Todd Holmes and Cristina Kim on the various ways to share oral history interviews with a wider audience. The OHC staff was, as always, excited to share their skills to expand the field of oral history practitioners and to learn about the innovative projects workshop participants proposed.

The OHC is committed to the University of California’s teaching mission and as such, we are always striving to improve our workshop. Each year we provide our participants with evaluations, which we take very seriously. This year we are happy to report that all of our participants stated that they felt ready to start conducting their own oral history interviews upon completing the workshop. As one participant triumphantly wrote in her evaluation, “I feel like I have much more clarity on my project, know what questions to ask myself and how to proceed.”

The OHC staff is already looking forward to next year’s Spring Workshop. However, until then, we are keeping busy and already deep in the throes of planning the Advanced Oral History Summer Institute.

Although we currently have a waiting list for the 2017 Summer Institute, it is never too late to ask yourself: Did you miss us this past February and want to learn more about oral history? Do you want to workshop your project with other oral history scholars? Do you have a research project that could benefit from the application of oral history methods?

If you answered yes to any of these questions, think about adding your name to the waitlist for the 2017 Advanced Oral History Summer Institute, or set a reminder to apply for the 2018 Summer Institute! For more information on our week-long oral history intensive course visit our website. Applications are online and available here. We hope to see you this summer!

Oral Histories with Women at Berkeley

One of the great joys of being an oral historian is getting to speak with many different people. We have the privilege of asking them about their lives and allowing them to put their experiences in the context of larger historical trends. We get this chance every year when we interview people for our “Class of ’31” series in university history, which is funded through a small endowment.

We have used the “Class of ‘31” series over the past four years to increase the representation of women interviewed because such a small percentage of Berkeley oral histories historically have been with women. So, in 2013, we interviewed Anthropology Professor Laura Nader. In 2014, we interviewed Pacific Film Archive Director Emeritus Edith Kramer. In 2015, we interviewed higher education scholar Patricia Pelfrey (her interview is forthcoming). And, most recently, we interviewed Psychology Professor Susan Ervin-Tripp as our 2016 honoree. Ervin-Tripp’s numerous nominations were among the strongest we’ve had. Her nominations conveyed a resounding eagerness to document her work in academics and equity, knowing that we could all benefit from learning about her efforts as a trailblazer.

Now, just as we celebrate the appointment of Berkeley’s first female Chancellor in the person of Carol Christ, we hope to expand our documentation of women’s contributions to UC Berkeley through a new initiative called “Women Leaders at Berkeley.” Although just in its infancy, this new initiative promises to highlight the work of the many female leaders on campus who have added much to their respective fields of study. In many cases, they have also helped advance equity on campus and in higher education more broadly. If you want to see more interviews like those with Nader and Kramer, Pelfrey and Ervin-Tripp, we encourage you to support the “Women Leaders at Berkeley” fund.

Check back with us in the coming months – and years – to see the progress that we hope to make in increasing the representation of UC Berkeley women in the Oral History Center collection and, by extension, in documenting the important, indeed pivotal, contributions women have made to make Berkeley what it is today.

Shanna Farrell, Interviewer