Author: Paul Burnett

Winner of the Friesen Prize in Oral History Research

Announcing the Winner of the First Annual Friesen Prize in Oral History Research

Announcing the Winner of the First Annual Friesen Prize in Oral History Research

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library is pleased to announce that the winner of the first Carmel and Howard Friesen Prize in Oral History Research is Ricky Noel, for his paper, “Corporate Imperialist Medicine: Aramco’s Health Care Initiatives in Saudi Arabia 1945–1965.” Mr. Noel is a Berkeley undergraduate majoring in history.

The selection committee read the several submissions for the following criteria: How well oral histories are integrated within and essential to the overall essay; how creatively oral histories are used in the essay; and the overall quality and persuasiveness of the essay. Noel’s essay excelled in all three areas. Particularly notable is the fact that his paper demonstrates how oral history interviews can be a crucial, even transformative, source from which new and enlightening historical interpretations can be drawn. Noel drew upon the interviews of the ARAMCO project, which consists of twenty-one oral histories covering the history of the US-Saudi oil operation founded in the 1930s and then sold to the Saudis in 1980.

We applaud Mr. Noel for digging deep into the archives, reading through long and detailed oral histories, and, in the end, hitting pay dirt in terms of fascinating and consequential archival discoveries, such as the public health dimension to US investment in overseas industrial ventures, as is covered in this essay. In this time of remote research, we encourage all students to explore the 4,000 interviews in the Oral History Center online collection and, like Ricky Noel, produce meaningful original research.

Did Masks Work? — The 1918 Flu Pandemic and the Meaning of Layered Interventions

A large number of recent news items have reflected on our current crisis by looking to the past for comfort, commiseration, and even some answers. My own writing on this is no exception. However, we need to be very careful about how we use history to inform our current context.

“Were masks effective in the 1918 flu?”

I was recently asked this question for an article that just appeared in the Smithsonian Magazine. It’s a fascinating exploration of the politics of masks in California during the 1918 flu, and the fact that Mayor Davie of Oakland was jailed for not wearing a mask in Sacramento. However, my statement at the end of the article, applied historically, is not correct by itself. I’m quoted as saying the gauze masks of 1918, “may not have been much use to the user but did offer protection to those around them.” I had in mind the ultimate public health lessons learned from the 1918 flu way down the line, in a study concluded a little more than ten years ago.

But back in 1918, public health leaders who studied the problem thought that the mask laws and mask use by the public were minimally effective.

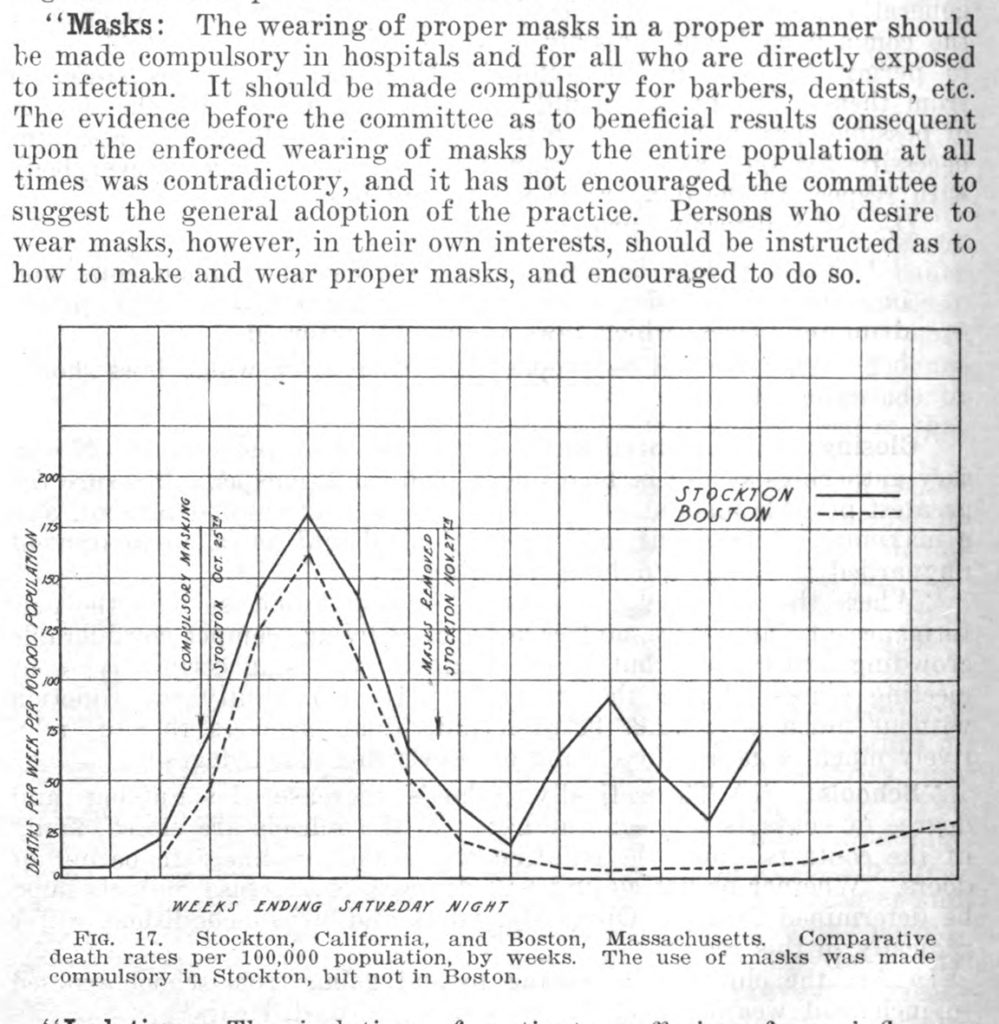

This is from a study published in 1919 by the California State Department of Health. The above graph showed very little difference in death rates between Stockton, which mandated the wearing of masks in public, and Boston, which did not. So, early on, authorities were skeptical of the effectiveness of masks, but they also felt that masks were not used properly.

Part of the disappointment was that medical authorities had advised using medical gauze, which had a tighter weave than what most people understood as “gauze.” Then as now, not everyone had access to the personal protective equipment solutions that were recommended. People were using cheese cloth for masks, with predictable outcomes. The problem was the user. A more pessimistic appraisal of masks came in a study published in 1921 by physician William T. Vaughan:

“One difficulty in the use of the face mask is the failure of cooperation on the part of the public. When, in pneumonia and influence wards, it has been nearly impossible to force the orderlies or even some of the physicians and nurses to wear their masks as prescribed, it is difficult to see how a general measure of this nature could be enforced in the community at large.”

William T. Vaughan, Influenza: An Epidemiologic Study, (Baltimore, MD: American Journal of Hygiene Monographic Series, No.1, 1921) 241.

Mask skepticism was officially sanctioned by the Surgeon General of the US Navy in a 1919 report:

“No evidence was presented which would justify compelling persons at large to wear masks during an epidemic. The mask is designed only to afford protection against a direct spray from the mouth of the carrier of pathogenic microorganisms … Masks of improper design, made of wide-mesh gauze, which rest against the mouth and nose, become wet with saliva, soiled with the fingers, and are changed infrequently, may lead to infection rather than prevent it, especially when worn by persons who have not even a rudimentary knowledge of the modes of transmission of the causative agents of communicable diseases.”

“Epidemiological and Statistical Data, US Navy, 1918,” Reprinted from the Annual Report of the Surgeon General, US Navy, (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1919) 434.

Although the Surgeon General of the US Navy acknowledged that wearing masks by hospital staff was good practice, “the morbidity rate, nevertheless, was very high among those attending the sick,” and may only have prevented infection from a direct, close hit from a cough or sneeze of a patient. The protocols followed in the contagious annex of the US Naval Hospital in Annapolis, MD, were sufficient to prevent cross-contamination of “cerebro-spinal fever” (aka meningitis), diphtheria, measles, mumps, scarlet fever, and German measles. Not so with influenza. In fact, the infection rate of staff was as high in the high-protocol wards as in the improvised hospitals. In one improvised hospital at the Navy Training Station in Great Lakes, IL., the infection rate was higher among those corpsmen and volunteers who wore masks than those who did not!

But what did all of this mean? Again, a discussion of a specific piece of technology by itself is not enough. This was not simply a question of “mask or no mask,” but of design, construction, supply, and use. The wearer needed to use a well-designed mask properly, and change masks frequently. Therefore, most of the expert complaints about masks around the Spanish Flu pandemic in the US seemed to be about the users and reliable access to steady supplies of properly constructed masks, not the concept of wearing a mask.

Indeed, that’s what the research team led by Howard Markel found when the Pentagon asked them to study the Spanish Flu pandemic. In 2007, they published their report on non-pharmaceutical interventions during epidemics and found that there was a “layered” effect of protection by using multiple techniques together: school closure, bans on public gathering, isolation and quarantine of the infected, limited closure of businesses, transportation restrictions, public risk communications, hygiene education, and wearing of masks.

So the key historical question here is not whether or not masks were useless. The broader, more troubling historical pattern that Erika Mailman revealed in her article is clear: the problem of public trust in public health. Some Americans, then as now, do not like being told what to do.

They especially do not like being instructed by “experts.” Americans arguably had more respect for expert authority during the flu pandemic than they do now, but even then, some would wear masks in public to comply with the law, then remove them when they went indoors, in close quarters with others and with poor air circulation, when they needed protection the most. Mayor Davie’s casual rebellion aside, citizens might grudgingly comply with the letter of the law, but not its scientific spirit. I’m reminded of a recent TikTok video of a woman in Kentucky who entered a store wearing a mask with a long slit around the mouth because it “makes it a lot easier to breathe.” Another problem, then as now, was that the right equipment in a time of crisis was unavailable. So people made masks with what they had available. But a cheesecloth mask was probably worse than no cloth, especially if they touched it frequently and changed it rarely.

A public health technology such as a mask is not just a simple, inanimate object. It’s the care with which it is designed and constructed; it is the infrastructure that can assure a steady, sanitary supply; it’s the use of one technology and practice in conjunction with others, and it is especially the informed users who take responsibility for their own health and those of their fellow Americans. Going back to the graph near the beginning of this blog post, we see that the curve of the death rate was bent by this layering of multiple public health interventions. Masks were not used widely and well enough to make much of a difference, but public health authorities tended to believe in their effectiveness for front line workers exposed to the worst of the flu pandemic. If we invested more in public health research, primary health care, and public health education, we could improve even more the quality and quantity of these layered non-pharmaceutical interventions, which worked together in 1918-19 and which are working now. We can do better with building our communication and trust so that all of these measures can work together. But for these to work together, we have to work together.

From the Oral History Center Director — May 2020

From the OHC Director — May 2020

I’m not the only one who has noticed that days seem to have become indistinguishable from one another — that the everyday cycles of life have become something of a blur. Thankfully there are still reminders of change and growth. At my home in Sonoma County, where I’ve been doing my SIP, we had a peek at summer last week when temperatures jumped unto the upper 80s and where, in my garage, my very first brood of chicks is quickly becoming a gang of unruly teenagers. And while our campus remains closed, another school year is just about wrapped up and with it (remote) celebrations for our graduating seniors. In recent years, we’ve worked with an increasing number of undergrads as employees and as apprentices and this year we commend and congratulate these Golden Bears for their contributions to our campus and achievements in the classroom: Gurshaant Bassi, Emily Keats, Nidah Khalid, Emily Lempko, Devin Lizardi, JD Mireles, Kendall Stevens, and Calvin Tang.

Last month in the April newsletter, I wrote about how the Center’s staff was working to bring our usual face-to-face operations into the Zoom Age by exploring the viability of high-quality online interviewing. Our working group, consisting of Paul Burnett, David Dunham, and Roger Eardley-Pryor, has devoted many hours to considering the possibilities and testing the options. I’m very pleased to report that they have developed a menu of workable options that accommodate the varying technological capabilities of our diverse set of narrators, as well as should meet the high expectations of our partners. I’m also very happy to report that at least one of our partner organizations has agreed to sponsor an online life history interview with a key individual in their organization’s history. As the OHC working group tests and fine-tunes their methods, they are documenting the specific processes and writing instructions. Once we’re confident that we’ve found the best possible process (given our uncertain and changing circumstances) we will happily share this with the oral history community. More than anything, we want to continue to do the important work of documenting lives and recording stories so that vital first person accounts of these remarkable and trying times are not lost to history — and we want you to be able to continue this work too!

Speaking of retrofitting for the ‘new normal,’ we are bringing other initiatives online too. Our Summer Institute this year is going virtual, for one. Registration is now open and keep in touch for more information on how the 2020 Institute is going to be run. Moreover, the May newsletter is usually our opportunity to celebrate and express our gratitude for those we interviewed during the previous year. Every April for the past six years, we’ve hosted an “Oral History Commencement,” that brought these folks together for a joyous event on the Berkeley campus. Alas, we’ve had to cancel the event for 2020 but still want to pay due attention to our narrators from the Oral History Class of 2020! Please come back next month for our virtual celebration of those who contributed their time and stories to the ever-growing Oral History Center collection.

Martin Meeker, Charles B. Faulhaber Director

Dispatch from the OHC Director, April 2020

From the OHC Director, April 2020

I’ve been thinking a great deal of late about what it means to live a life connected or disconnected or perhaps something in between. I suspect I’m not alone in pondering these states of being — a kind of remote engagement that itself feels a little bit like connection.

Oral history is about many things: listening, documenting, questioning, recording, explaining. I think connection is always key to the work that we do as oral historians. But like many other operations, including basically all non-medical research projects that involve humans, our work conducting interviews is largely shut-down while we consider how best to forge ahead.

My colleagues and I have always valued the importance of the in-person, face-to-face interviewing experience. We regularly travel across the country at some considerable expense just so we can be in the same room with the person we are interviewing. We have found this time in close proximity with our narrators to be priceless. Not only does this allow us to shake hands, look eye-to-eye, and gauge body language just before and during the interview, but also these are practices that, until recently, have been second nature — we usually do them without thinking much about it. There really is an unconscious kind of dance that happens, especially when meeting someone for the first time, that in most instances results in a spontaneously choreographed fluidity that can carry the ensuring interview through fond memories and bad. Because of this, up to this point, only when it really was impossible to meet in person have we conducted an interview over the phone or online.

But times change. The current health crisis has profoundly rearranged social relationships, and likely for some time into the future. (Dr. Fauci even suggested that we rethink the practice of shaking hands, which, I’ll admit, makes me sad.) The Oral History Center staff have been scattered now for over a month. But we have endeavored to not lose touch with one another. Thanks to multifarious technological options, we have easily transitioned our weekly staff meetings online. We use either Google Hangouts or Zoom and, so far, everyone has used video, so we get to hear each other’s voices and see faces too. We sometimes have agenda items that require lengthy discussion, at other times we simply check in with each other about work but also about “how things are going.” We live in different settings so people have different challenges and we do our best to touch on those. I also chat every week with each of my colleagues individually and I’m very pleased to know that my colleagues have been meeting with each other, doing their best to push projects forward. The success of these virtual meetings, and, well, the zeitgeist, inspired me to set up virtual happy hours with friends and family. My family lives across the country and it’s been probably four years since we’ve been in the same room together but for the past two weeks we’ve all gathered online to check in, tell stories, have some laughs, get serious and, of course, get photobombed by various kids and dogs. We don’t escape the underlying gravity of the current situation, but this hasn’t stopped connection — in some real ways it has promoted it.

So, with this in mind, we are exploring the options for bringing our oral history back to life by bringing it online. We’re currently testing out various options for video and audio recording, paying close attention to everything from quality of recording to ease of use (considering that most people we interview don’t fit within the “digital native” demographic). We also are sensitive to the dimension of personal connection, rapport, and understanding, but given recent experiences “at” home and “in” the office, we have reason to be optimistic. The reasons for going online are not only about opportunity, they are much deeper and in some ways quite profound: every day, every month that passes, we lose an opportunity to interview someone who should have had the opportunity to tell their story. In fact, we just learned the very sad news that artist and advocate of Black artists, David Driskell, passed away due to complications from COVID-19. This was a man with a story to be told — and thankfully, with our partners at the Getty Trust, we conducted his oral history last year. We simply cannot wait out this epidemic and let it steal stories along with lives.

The second profound reason is related to something I’ve mentioned rather delicately here in the past: that the Oral History Center is a soft-money institution. What that means is we are basically a non-profit that earns its money (allowing us to do our work) by conducting interviews. The longer we are prevented from conducting oral histories, the more precarious our position becomes. We hope for but do not anticipate relief from the university, the state, or the federal government. All we want is to resume the good work of documenting our shared and individual experiences in times of growth and times of challenge — to continue the work that we’ve done for the past 66 years.

As we consider the path ahead, the Oral History Center staff continues to work vigorously albeit remotely. We’re finishing the production process on dozens of interviews that have been conducted already — that is, writing tables of contents, working with narrators on edits for accuracy and clarity, creating the final transcripts for bound volumes and open access on our websites. We continue to process original audio and video recordings so that they can be uploaded to our online oral history viewer. We’re writing blog posts about oral history and producing podcasts, including our newest and very topical season, Coronavirus Relief. Plus in addition to the regular work, we’re using this opportunity to focus on long desired projects: We’re creating curriculum for high schools; we’re writing abstracts for old interviews that never had them; and we’re using this time to think about new projects and write grant proposals so that when the time comes, we’ll be ready to go full steam ahead.

Check back here next month for more on our efforts to move oral history online. We’ll share our results publicly as many others are venturing into this domain too — and have themselves made important contributions to the conversation (I especially recommend checking out the free Baylor / OHA webinar on “Oral History at a Distance”). Until then, we sincerely hope that everyone this newsletter reaches stays safe, healthy, and able to remain connected to those who are important to you.

Martin Meeker, Charles B. Faulhaber Director, Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library

Dying by Inches: Epidemics and Oral History

Many comparisons have recently been made between COVID-19 and the great Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918-19. There has also been a lot of great research by historians into that pandemic, specifically to discover any lessons that might apply to future pandemics. Historians of medicine Howard Markel and Alexandra Stern at the University of Michigan conducted a large study of the Spanish Flu in the wake of the SARS epidemic in the early 2000s. One of the most important lessons they learned was the difference that social distancing could make. Remember the graph that was in the news early on in the COVID-19 pandemic which showed the differences in case-fatality rates between Philadelphia and St. Louis? This is where the evidence for the concept of “flattening the curve” comes from. The results were published in the Journal of the American Medical Association. Researchers from the same effort then compiled all kinds of information in an online encyclopedia of the Spanish Flu.

We at the Oral History Center at UC Berkeley have our own stories that touch on the Spanish Flu. Using our “Advanced Search” fields in our collection’s search engine, you can search using a number of terms to bring up these oral histories. I found eight for “Spanish Flu,” accounting for duplications. But it’s important to try different search terms. When I searched “flu” and “1918,” I got 591 hits. And when I pull up an oral history in PDF form by clicking “view transcript,” I hit Ctrl-F (or Command-F if you have a Mac), and type a search term into the field. When I hit “Enter,” I’m taken right to each location in the transcript where that word is mentioned, in sequence. A lot of the mentions of flu come from our Rosie the Riveter World War II Homefront Project and a series on Russian immigrants to the US that was conducted by UC Berkeley Professor Richard A. Pierce in the 1960s and 70s.

Usually there is just a brief mention or anecdote about that dreadful year 1918, as these are life histories about much more than that time of crisis. But what’s striking about these narratives is just how much was going on at the time. First of all, there was a world war that had claimed the lives of tens of millions of people. Social order had disintegrated across much of Eurasia; harvests were not attended to; revolution was overturning society in Russia; Russian Jews were being killed and displaced in pogroms, and millions of young men were returning from the Great War to their homes thousands of miles away, in many cases bringing new and unfamiliar germs along with them back to their families and communities. In addition, organized national public health institutions were underdeveloped in many countries, including in the United States. The newly named US Public Health Service was only six years old when the flu struck, and the germ theory of disease had only begun to shape public health policy over the previous few decades. Then, as now, states and municipalities in the US had widely varying responses to the epidemic. Furthermore, no one knew exactly what viruses were at the time. Though much larger bacteria and parasites could be seen under a basic microscope, viruses were defined as undetectable substances that passed through the finest filters they had for measuring particles. So, in addition to a poor understanding of the nature of viruses, part of what made the Spanish Flu so devastating was that human bodies in 1918 were in general more vulnerable to disease at that particular moment because of all of the other factors that tended to cluster around epidemics: war, famine, persecution, and mass refugee migration.

Here Cal professor of business Jacob Marschak reminisces with his sister Frances and historian Richard Pierce about fleeing the Bolsheviks during the Russian Civil War, on a boat to Sevastopol:

Jacob Marschak: That was already after the Armistice, and there were many German prisoners returning. The Spanish flu was then raging, and was quite devastating. Many died of it. On the boat I got a terrible attack of it, and my sister nursed me. One man died of it and we buried him at sea.

Frances Sobotka: On the steamer he was severely ill with Spanish flu; I didn’t get it but he did, and it was very hard on him, because it was already about October, very cold, and he had the highest fever that I ever knew, and we had only places to be on the deck. Then somebody allowed him to go and stay in the machine compartment, which was too hot, and he always had a bottle of cognac with him. He was no more a drunkard than you or I, but somebody told him that it was the best thing against Spanish flu. By the time we reached Sevastopol he could already walk, but he was still very weak, and held my shoulder as if I was his stick.

Jacob Marschak, “Recollections of Kiev and the Northern Caucasus, 1917-18,” conducted by Richard A. Pierce in 1968 (Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 1971) 75.

Fate, chance, and one’s family, social, and financial resources helped determine who lived and died. Mary Prout, one of the narrators for our Rosie the Riveter WWII Home Front Project, describes her aunt’s good fortune when the flu came for her. Here she is from an interview in 2002 with Ben Bicais:

My mother was a housewife, but she became a nurse before my mom and dad got married. An excellent nurse, loved it. But her father didn’t want her to become a nurse because he felt that it was too hard on girls. They had to do all the custodial work and everything. So she said, “Okay, Father, I’ll graduate from high school, and then in three years I’m going to go to become a nurse.” And he said, “That’s fair enough.” So she had a young sister, and in three years, they both went to Mary’s Help [Hospital], both became RNs. Then after— well, it was after the war, I guess, my aunt was just a little gal, and she was getting that virulent flu that they had then, that terrible flu. It was just awful. So my mother knew that she wouldn’t live through it. So Mom tried to get an ambulance, but she couldn’t find one, so she got a hearse, and she went down to the veteran’s hospital in Palo Alto, picked up my aunt and saved her life, really. … Oh, yes, that was terrible. People were dying by the inches.

Mary Hall Prout, “Rosie the Riveter World War II American Home Front Oral History Project” conducted by Ben Bicais in 2002, (Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 2002) 27.

Things were bad enough here in the US, but in Russia, years of war and the Bolshevik Revolution had depleted supplies of food, and people had to barter away the last of their possessions for scraps. Russian émigré Valentina Vernon, whom historian Richard Pierce interviewed in 1980, described her diet in 1918:

Vernon: We ground that horrible stuff, and then used the skins from the potatoes you could get a few of potatoes, they were a sort of luxury. The skins were put in the oven and dried out and made into a powder, and the cakes made out of the dried vegetables were rolled in the black stuff and fried in coco-butter. Awful! There was no butter, but you still could find some coconut. And then the dried fish (seledki) , that was the main supply of food. So naturally we lost some weight. And this was our existence until we left.

Pierce: When did you leave?

Vernon: In September, 1918, just 18 days before the birth of my son. I had the Spanish flu, but I didn’t die, and my son didn’t either. Like the doctor here, who says Russian women are awfully tough! But my sister-in-law refused to leave, and they shot her husband. (Vernon, 1980, 15)

Another émigré, Boris Shebeko, describes his experiences during the First World War and the Russian Civil War in his oral history. Since I couldn’t search this PDF – which was just a scan of an old photostat copy – I started scrolling through the transcript for references around the time period of the end of World War One. I quickly became immersed in the stories. He seemed to careen from one life-threatening experience to another: almost being overtaken by singing Cossacks, who rode their horses directly into his machine-gun fire; stepping over giant cracks on a march across the frozen Lake Baikal; or getting into a knife-fight with French sailors in Constantinople. He even suspected his colleague of being a serial killer! The Spanish Flu was just one of his problems in those days.

Boris Shebeko, “Boris Shebeko: Russian Civil War 1918-1922 and Emigration,” conducted by Richard Pierce in 1960. Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 1961.

After reading through these fascinating stories, I was left wondering what influenza meant in those chaotic contexts of war, migration, and near-starvation. In 1918, the global circulation of people was higher than at any time in history. And by some measures, the world was much more interconnected in 1918 than it was even as late as the 1970s. In 2020, we have our own special mix of challenges. We are clearly, obviously much more interconnected on a global scale. In 2018, there were 4.3 billion passengers on flights. Add this incredible daily migration across the globe to our exposure to ecosystems that had until now been isolated from this global community, and we see an increase in our exposure to germs to which we have no natural immunity. We call these new epidemics —SARS, Zika, Ebola, COVID-19—”emerging” diseases for these reasons. Although we know so much more about viruses and how to treat them than we did in 1918, we have not learned as much as we could from previous pandemics. Scarier yet, the knowledge we do have has not guided policy, and in some ways we are still very much flying blind in this pandemic.

What do these oral histories tell us about epidemics? As horrifying and tragic as some of these stories are, they are the stories of survivors, those who were lucky, resourceful, and somehow positioned well enough to help themselves or to help others. As we learned in our First Response podcast, about the early AIDS epidemic in San Francisco, people tend to have two basic reactions in epidemics: fear, which can lead to scapegoating and selfishness; and love, sympathy, and a sense of duty to family, communities and even to complete strangers, which lead to mutual aid, careful planning, adaptation to changing circumstances, and rational action based on the available facts. Let’s allow these histories of resilient survivors to be our guides, now and into the future.

Paul Burnett

OHC Director’s Column – March 2020

From the Director — March 2020

From all of us at the Oral History Center, we are wishing you our best in these challenging times. We hope that you’re doing your best to get through the coming days, and above all, you and your loved ones are staying safe and healthy.

In a recent oral history, George Miller discussed the idea of the dreaded “Black Swan” event that might strike at a moment’s notice, leaving destruction and disruption in its wake. But Miller has artfully crafted a healthy sense of informed detachment and thus always used these events as an opportunity for learning and reflection. Perhaps the greatest lesson from the Black Swan events he experienced in the world of finance was that we always came out the other side — maybe a bit bruised but ready to face another day. So, as many of us sit at home, self-isolating, I invite you to take a break from the constant news feed of what is happening right now and instead spend some time in the past. Delve into the OHC archive of transcripts and recordings and expose yourself, for example, to many individuals who achieved great things in their lives but who each experienced Black Swan events of their own. Trial and turbulence, patience and perseverance.

Perhaps not surprisingly, many of the most remarkable of these stories come from women we’ve interviewed, in particular those women who broke glass ceilings in the workplace and the realm of politics. We’re currently developing a database documenting the hundreds of women we’ve interviewed over the years who were connected to the University of California — as part of the 150 Years of Women at Berkeley celebration. And we continue to contribute to this history with plenty of recent interviews, including female students who were active in the SLATE organization on campus in the 1950s and 60s. And then many more interviews with women who persevered while working in support of the arts (Kathleen Dardes), the environment (Michelle Perrault), and public service (Anne Halsted). You’ll see a handful of those stories referenced in this newsletter but I encourage you to just jump in, browse the collection (our Projects page is the best way to do this), and allow the thousands of life stories we’ve collected give you reassurance, perspective, and company.

Finally, we’ve made the decision to postpone our annual Oral History Commencement in which we invite our interviewees to campus for a lively celebration of oral histories completed in the past year. We still want to express our gratitude to our narrators, so stayed tuned.

Martin Meeker, Charles B. Faulhaber Director of the Oral History Center

OHC Director’s Column – February 2020

From the OHC Director…

Berkeley students and researchers from around the country reach out to us, especially during Black History Month, interested in our oral histories with African Americans. We always point people in the direction of our African American Faculty and Senior Staff oral history project, otherwise known as The Originals. And there is a good reason we do that: this project features seventeen lengthy and substantive oral histories with leading and pioneering UC Berkeley scholars and administrators (more on this below). But limiting our reference to this single project does service neither to OHC’s full collection nor to the amazing and accomplished individuals interviewed for other projects or simply based on their own merits. In preparation for this month’s column, I spent a day digging into our collection in an effort to uncover a host of hidden gems — in this case, interviews with African Americans whose living memories date to the early 20th century (at least) and offer first-person insights into the life of a Tuskegee airman, the contours of the West Coast jazz scene, the role of women in the Black Panthers, and much more.

The migration of African Americans from the American South to the industrial centers of Northern California in World War II changed those who moved, along with the places they moved to. Drawn to jobs in places like the Kaiser Shipyards in Richmond, California, these migrants set down their roots in the Bay Area. In some interviews from the Rosie the Riveter / World War Two Home Front oral history project, Black “Rosies” tell about their lives in Jim Crow South, about the migration north and the hope for a better life, and about their experiences working in wartime industries and experiencing both greater opportunity but still discrimination based on race. Of the 197 Rosie project oral history, about a quarter are with African American women and men. It is likely folly to pull out one interview from this group, but I’m certain people will be interested in the story of Betty Reid Soskin, who not only worked in Richmond during the war but decades later became a ranger with the National Park Service at the Rosie the Riveter National Historic Site. Reid Soskin continues to work at the park today — at the ripe young age of 98!

One chapter in the Second World War that tragically demonstrated the enduring power of racism was the Port Chicago Disaster of 1944. The majority of the 320 killed and 340 injured in this accidental munitions explosion were African American. The eight oral histories of the Port Chicago project were recorded in the late 1970s and early 1980s by UC Berkeley scholar Robert Allen (whose life history interview we will be released this spring).

Our documentation of the African American experience in the Bay Area continues well past World War II. In a few major projects, Black East Bay residents — and their neighbors — offer accounts of not only the transformation during war but the important decades that followed. The On the Waterfront project follows several narrators through these decades. In the Oakland Army Base project, we hear from several African Americans (Charles Snipes, Cleophas Williams, Davetta Thibeaux, Ellen Wyrick-Parkinson, Elois Thornton, George Bolton, George Cobbs, Gordon Coleman, Grant Davis, Leo Robinson, Louis Harris, Margaret Gordon, Michael Thomas, Monsa Nitoto, Queen Thurston, and Robert Taylor) about their interactions with base, whether as a member of the military service, an employee of the Department of Defense, or as a resident of the nearby community of West Oakland.

The Civil Rights Movement is documented in our collection (though, admittedly, many more oral histories can be found elsewhere, such as at the Library of Congress), particularly as it

manifested in the San Francisco Bay Area in organizations that likely deserve more attention from researchers. Frances Mary Albrier was elected in the 1930s to the local Democratic Party Central Committee (and was welder during the war) and Terea Pittman became a leader of the NAACP (and many other organizations) in the earliest years of the Civil Rights Movement. The Council for Civic Unity, in addition, was established in the 1940s and was an important precursor to the California Fair Employment Practices Commission; Charles Patterson, in his interview, tells about the organization for which he was an intern before becoming a major figure in the foundation world (along with Ira DeVoyd Hall, who was a leader of the San Francisco Foundation). Orville Luster, who was interviewed in 1975, recalled his leadership of the unique Youth for Service organization which taught disadvantaged youth the skills necessary to be successful at work. And there is always a good deal of interest in the interview we hold with Ericka Huggins of the Black Panthers, which was donated to us by Fiona Thompson.

African Americans, not surprisingly, have played key roles in social justice work beyond the 1960s Civil Rights Movement. Henry Clark and Ahmadia Thomas and Carl Anthony were interviewed for their groundbreaking work in the area of environmental justice, while Michael Crawford and John Newsome were interviewed for our large project on Freedom to Marry, or the fight to win marriage equality. For our major project documenting the history of the Disability Rights and Independent Living Movements, we interviewed Chester Finn, Victor Robinson, and others.

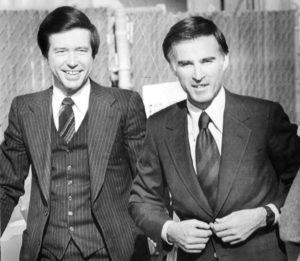

Movement politics and protest is one way to force change, building institutions and running for elected office are other avenues pursued by African Americans we’ve interviewed over the years. I encourage you to read through two very interesting oral histories with three influential elected officials, Oakland Mayor Lionel Wilson and California State Assemblymen William Byron Rumford and Willie Brown (the second part of Brown’s oral history, covering his terms as San Francisco Mayor, will be released this spring). African Americans have made signal contributions to the law, as well: Cecil Poole, the first African American appointed as a United States Attorney in 1961, later became a distinguished federal judge; Allen Broussard rose up through the ranks of city and county courts, eventually joining the California State Supreme Court in 1981 as an associate justice; and to this day, US District Court Judge Thelton Henderson plays an outsized role in the area of law and civil rights.

Law and politics are only two venues in which an individual can make an impact as the ethos of public service runs through many other institutional domains. Born just over 120 years ago, C.L. Dellums led a life of public service through many offices, perhaps most notably as through his decades as Vice President and then President of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. After he had already done important work integrating the department, Robert Demmons was appointed the first African American Chief of the San Francisco Fire Department by Willie Brown in 1996. Everett Brandon might be little remembered today, but as a young man, he was a leader in San Francisco’s War on Poverty programs which brought services and employment to thousands of in the city. In recent decades, Joseph Marshall has continued the work of Brandon and others through his Omega Boys Club / Alive and Free service organization in San Francisco. The spirit of public service thrives in the private sector too. Our interviews with Ron Knox and Amanda Brown reveal how one of the largest private health care providers in the country have fought to improve health outcomes for African Americans.

The Oral History Center has long been committed to documenting our culture well beyond politics, law, and public service — we are deeply interested in the arts and the people who create them. Longtime OHC historian Caroline Crawford held an ongoing interest in documenting African American contributions to the arts, particularly music. Her interviews with Allen Smith (jazz trumpeter), Earl Watkins (jazz drummer), Gildo Mahones (jazz composer and pianist), John Handy (saxophonist, composer, and bandleader), and Jimmy McCracklin (blues singer and pianist).

Finally, I want to bring this back around to education, as this is the root of all good things (dare I say) and I think it is essential for a university to document its role in improving society and creating new possibilities. I very much encourage you to take a deep dive into the African American Faculty and Senior Staff project, perhaps beginning with a 20 minute video we produced a few years back. This project, however, was years in the making and while we refer to this group of early faculty and staff as “the Originals,” the truth is that they weren’t the first. Our interview with Archie Williams is a true hidden gem of the collection. Williams attended Berkeley between 1935 and 1939, which was punctuated by an appearance at the infamous 1936 Olympics in Berlin at which he won a gold medal. Although too old to serve in a combat role in World War II, as a certified pilot he trained the Tuskegee airmen! He went on to a career as a respected educator. Marvin Poston was a student at Berkeley at the same time as Williams and eventually became a widely respected optometrist. In 1958, Robert Gibson was the first African American to earn a doctorate in pharmacy at UCSF, where he became a distinguished member of the faculty. Born in 1920, Emmett Rice earned his doctorate in economics at Berkeley in 1954, before being named to the Federal Reserve Board of Governors in 1979; it is worth noting that Rice’s daughter is Susan Rice, who served as UN Ambassador and National Security Advisor in the Obama Administration. A graduate of San Diego State, Del Anderson Handy had a distinguished career in education, culminating with a term as chancellor of San Francisco City College.

These oral histories represent a meaningful slice of OHC’s interviews with African Americans, but surely not the entirety of the collection. The Oral History Center encourages you to not only explore the interviews listed above, but dig even deeper into our collection, honoring the voices of those African Americans we interviewed by reading their words and absorbing their ideas and experiences.

Martin Meeker, Charles B. Faulhaber Director

Find these interviews and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. You can also find the projects mentioned here on our projects page.

Governor Gray Davis on Governor Jerry Brown

Editor’s note: Gray Davis, the 37th Governor of the State of California, served as chief of staff to Jerry Brown during his first two terms as governor (1975-1981). We asked Gov. Davis to write a foreword to our lengthy oral history with Brown, which we are pleased to share with you below. Click here to see Davis’s essay in the context of Brown’s oral history. See more resources on the Jerry Brown oral history.

*******

Governor Edmund G. (“Jerry”) Brown was the longest serving governor in California history, and one of the most consequential. First elected in 1974, he championed a major solar initiative (first-ever tax incentive for rooftop solar), and signed legislation prohibiting any new nuclear power plants in California until the federal government certified a safe way to dispose of nuclear waste. To this day, the Federal Government has yet to do so and no further nuclear plants have been approved.

Governor Brown also negotiated and signed the California Agricultural Labor Relations Act of 1975, a first of its kind in California and the Nation. Even today, it remains the only law that creates and protects the rights of farmworkers to unionize and collectively bargain. None of the other 49 states has been able to pass similar protections for some of the most vulnerable workers in our country.

In March of 1976, Jerry announced his run for the presidency and won primaries in California, Maryland and Nevada, and accumulated the second highest number of votes going into the convention (2,449,374). His late entry into the 1976 democratic presidential primary precluded him from catching Jimmy Carter, who accumulated the requisite amount of delegates to secure the nomination and become president.

Jerry Brown left office in 1983 and did not return to the governorship until 2011, 28 years later, making him California’s youngest, oldest and longest-serving governor. His third and fourth terms featured a remarkable turnaround in the state’s financial standing. He inherited a $27 billion deficit but left office with a $29 billion surplus ($14.5 budget surplus and a $14.5 billion “rainy-day fund”).

In an effort to restore the State’s fiscal stability, Jerry sponsored and campaigned for the passage of Proposition 30, a voter-approved tax increase that raised $6 billion. Tying his fiscal and environmental stewardship together, in 2012 Jerry signed into law the first in the nation government run cap-and-trade program, creating in excess of $9.3 billion to fund emission reductions and programs that protect the environment and promote public health.

He left the Governor’s office and public life in early 2019, enjoying a higher approval rating than any governor since Ronald Reagan.

To understand Jerry’s expansive worldview and insatiable curiosity, it is helpful to take stock of where he has been and what he has done. The son of a Governor, he lived in the Historic Governor’s Mansion, attended parochial high school, studied at Santa Clara University, joined the Sacred Heart Jesuit Novitiate seminary, received his Bachelor’s Degree from UC Berkeley and his law degree from Yale. In addition, Jerry has practiced private law at Tuttle and Taylor, was elected to the Los Angeles Community College Board of Trustees, California Secretary of State, California Attorney General and four times as Governor of California. He has run the State Democratic Party, served as Mayor of Oakland and ran three times for president. He’s traveled the world, studied Buddhism, and worked with Mother Teresa at her Home for the Dying in India.

When I was running for governor, people asked me what does it take to be a successful governor? My answer (in jest) was “rain in the north and a strong economy.” Obviously, the governor cannot affect the weather. As for the economy, state tax incentives can only affect the economy on the margins. In the main, economic expansions and recessions are a result of the business cycle and function largely outside the Governor’s control.

But that is not how the public sees it. They give great credit to a governor when the economy is improving, but hold him fully accountable when the economy is in recession. Every governor from Ronald Reagan has experienced a slowdown or recession of some type. Reagan, Jerry Brown in his first two terms, Deukmejian, Wilson, myself and Schwarzenegger have experienced the ups and downs of the economy.

But when Jerry Brown was inaugurated for the third time in 2011, the economy turned positive and remained positive for his entire eight years.

That was a great relief to the public whom had experienced an unemployment rate of 10%, the loss of thousands of homes to foreclosures and financial downgrades, as conditions deteriorated in California.

This economic rebound was a critical factor in rescuing California from nearly a decade of deficits; however, it took more than good luck to turn California around. Jerry Brown brought the fiscal discipline necessary to turn the corner. He had reached out to almost every legislator as soon as he was elected for the third time, explaining that the path of more borrowing and larger deficits was not sustainable.

Despite hundreds of hours of collaboration with the legislature, their initial budget was a disappointment to him and was clearly not in balance. After much deliberation he decided to do something that has never happened in California: he didn’t just veto parts of the budget as most governors in the past had done, he vetoed the entire budget!

Sacramento was in shock!

After a number of heated meetings, he and the legislature produced a second budget with numerous reductions that was in balance, and put California back on the path back to solvency. As a result of that budget and previous cuts, some 30,000 teachers had been laid off, many classes had been canceled as well as almost all after school programs in California. In his 2012 budget, the governor and legislature restored some, but not all, of the cuts made during the previous three years.

That same year, the Governor gambled that he could persuade voters to pass Prop 30, which generated $6 billion additional dollars that paid for these new teachers and professors and restored many of the classes that had been eliminated in previous years. In fact, the voters believed Jerry Brown when he said California could not cut anymore. They believed him when he said that most of the taxes would fall on the wealthy and that Prop 30 would put California back on the path to greatness.

The voters passed Prop 30 and gave California a fresh start.

A governor without Governor Brown’s discipline and well-known frugality might not have convinced California voters to increase taxes by $6 billion. Without Jerry Brown’s leadership, cooperation of the legislature and the strong economy he inherited, California might still be waist deep in deficits rather than the 5th largest economy in the world. Jerry Brown exited the stage in January 2019. By the time he left, California had new problems, including homelessness and poverty; but he and the legislature solved the problems they inherited by righting California’s finances and helping rebuild its economy.

Frugality and Good Fortune:

Before Governor Brown was inaugurated in 1975, he told me he did not want to be driven in a limousine, but preferred instead a car normally assigned to a legislator or cabinet officer. When I conveyed that message to the director of general services, he told me they had 1974 Plymouths available in three colors: gold, white and blue. I opted for blue, envisioning dark blue or royal blue.

After the Governor delivered a 7-minute inaugural address, we started walking across Capitol Park for our trip to San Francisco. There was only one car waiting for us – and it was not the dark blue Plymouth I anticipated but a powder blue Plymouth! No California governor has ever been a driven around in a powder blue Plymouth. I was beyond embarrassed!

“Is that my car?” Governor Brown asked. “I’m afraid it is,” I replied.

But to the Governor’s great good fortune, the public warmed up to the idea of a powder blue Plymouth; they began to take pride that their Governor had chosen a less expensive and less imposing looking car as his official vehicle. By the end of Jerry’s second term, the blue Plymouth became almost as recognizable as the Governor.

Another example of the governor’s frugality occurred about three months into his administration. We were just finishing our morning meeting, when I mentioned to the governor that I had asked General Services to come over and not replace, but repair a 10-inch hole in the rug adjacent to his desk. “Why would you do that?” he asked. “Because it’s unseemly to have a hole in the governor’s rug.” The Governor answered: “That hole will save the state at least $500 million, because legislators cannot come down and pound on my desk demanding lots of money for their pet programs while looking at a hole in my rug!”

That told me not only was the governor genuinely frugal, but that he also understood the power of his frugality to fight off excessive demands in the budget. It gave him the moral authority to ask for big cuts when the state was $27 billion in debt at the start of his third term, and the courage to veto the entire budget when they did not make those cuts.

Jerry Brown was the best and possibly the only leader who could overcome the challenges that California faced in 2011 and lead the state back to the 5th largest economy in the world.

When he walked out of his office for the last time in January 2019, only the United States, China, Japan and Germany had larger economies than California.

By Governor Gray Davis (Ret.), 37th Governor of California

OHC Director’s Column – January 2020

From the OHC Director:

The staff of the Oral History Center wishes everyone a happy and productive 2020!

After a long winter’s rest for the Berkeley band of oral historians, this year has jumped off to a running — and even wild — start.

For one, we have begun the unveiling of our lengthy life history interview with four-term California Governor Jerry Brown. Done in partnership with KQED Public Media, this oral history also serves as the first interview conducted for the relaunched California State Government Oral History Project, a project of the Secretary of State. Read more about the interview background and context — or the interview itself. Here’s the page that serves as clearing house for all information about and coverage of this important oral history

We are in the final phases of preparing a number of new interviews for release in the coming weeks and months, including new releases for our projects with: the Sierra Club, the East Bay Regional Park District, the Presidio Trust, San Francisco Opera, the founders of Chicano/a Studies, and the Getty Trust African American Artist project.

Along with our usual oral history work, we are preparing for our annual Introductory Workshop (Leap Day! February 29th) and Advanced Summer Institute (August 10–14). Applications for the Introductory Workshop and Advanced Institute are both now open.

Come back in February for a more substantive column from your’s truly. Until then, back to that reservoir of unread emails!

Martin Meeker, Oral History Center Director

New Release Oral History: Jerry Brown: A Life in California Politics

New Release Oral History: Jerry Brown: A Life in California Politics

By Martin Meeker, Charles B. Faulhaber Director, Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library

There are very few individuals who are what might be called a “shoe-in” for an Oral History Center life history interview. Governor Jerry Brown is one who easily qualifies. Brown’s career as an elected official began in Southern California in 1969 when he was elected to the Los Angeles Community College Board of Trustees and then continued for nearly the next fifty years through a succession of high offices. He was elected: in 1970 to serve as California Secretary of State; in 1974 and again in 1978 as California Governor; in 1998 and 2002 as Mayor of Oakland; in 2006 as California Attorney General; and, finally, in 2010 and 2014 as Governor of California, for a third and record fourth term. In the midst of, and in between these offices, he ran three times for President of the United States (1976, 1980, and 1992), he once was the Democratic Party nominee for the U.S. Senate in California (1982), was elected chair of the California Democratic Party (1989), and ran his own nonprofit, populist, quasi-political organization We the People out of a communal living space he custom-built in Oakland, California in the 1990s. For the historians at UC Berkeley’s Oral History Center, the question was not, “Should this interview be done?” but rather, “How might it be done at all?”

Edmund Gerald “Jerry” Brown Jr. was born April 7, 1938, in San Francisco, California. At the time of his birth, his father, Edmund Brown Sr., whom everyone knew as ‘Pat,’ already was deeply involved in the law and politics of San Francisco. He had a thriving law practice and had run for San Francisco District Attorney, with assistance from local players including William Newsom Sr., grandfather to the state’s current governor. After initial failures, Brown Sr. was elected district attorney (1943), then California Attorney General (in 1950 and 1954), and finally Governor of California in 1958 and 1962; he attempted to win a third term, but lost to Ronald Reagan in the watershed 1966 state election.

Pat Brown married Bernice Layne in 1930. Smart and educated at UC Berkeley, Bernice Layne Brown gave up an anticipated career in teaching for the roles of wife, mother, and homemaker, and was a forceful presence in the family and in the life of her only son, Jerry. Jerry Brown described his youth as a world apart from that of adults, not concerned with big issues or the problems of the day. Despite this, or perhaps because of it, he developed a yearning for something more meaningful in his life as he grew into a young adult. He was educated at Catholic parochial schools and after high school choose to attend Santa Clara College (now University), a Jesuit school, before abandoning that route in favor of a life in the Catholic priesthood. He lived for three years at the Sacred Heart Jesuit Novitiate seminary before then wanting a deeper engagement with the world around him, which led him to UC Berkeley in 1960. He graduated from Berkeley in 1961 and immediately was accepted to Yale Law School, which he completed in 1964. Jerry Brown clerked for California State Supreme Court Justice Mathew Tobriner while he studied for the California Bar Exam, at the time living in the California governor’s mansion near the end of his father’s second term. Approaching the age of thirty, Jerry Brown moved to Los Angeles, where he joined the Tuttle & Taylor law firm and would soon make the initial steps beginning his career in politics.

The Oral History Project

Working as an interviewer with the Oral History Center (OHC) since 2004, I was long aware that Jerry Brown had not yet sat for an oral history and that it would eventually need to be done — I might say that it was one of the interviews I personally wanted to work on and see to fruition. Then, in 2018, with the end of Jerry Brown’s fourth term as governor in sight, the OHC began the planning process, yet still without the necessary financial resources in place to make it happen. Because the University of California does not underwrite the Center’s oral history projects, we worked to secure funding for this interview, which clearly was going to be longer than most. In this context came a call from Scott Shafer, the senior politics editor with San Francisco’s KQED. Shafer inquired if OHC had begun “the governor’s” oral history. Shafer and I arranged to speak, during which he shared his hope of producing a multi-episode podcast series documenting Brown’s political life. I was intrigued with the notion of partnering with KQED and, especially, with a political reporter whose work I greatly admired. I recognized that adding additional people and institutions to the mix might complicate the process and potentially change the outcomes, but Shafer and I decided that a partnership might be mutually advantageous from several angles, so we drafted a working plan.

First off, we assembled a project team, the core members of which would be myself, Scott Shafer, KQED politics reporter Guy Marzorati, and OHC political historian Todd Holmes. Additional KQED staff, most notably Queena Kim, would participate by managing the recording of the interviews; OHC staff, most centrally Jill Schlessinger and David Dunham with the capable assistance of Berkeley undergraduate JD Mireles managed the production of the final transcript and the preservation of the recordings. The project team agreed to schedule all meetings and interview sessions at the convenience of the governor with the mutual agreement of all interviewers. OHC pledged to manage the paperwork, transcription, editing, reviewing, and finalization of the complete interview transcript. OHC, as a research unit within The Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley, would also preserve, archive, and provide public access to the transcript and audio recordings. It is worth noting that OHC typically video records its oral histories, but in a planning meeting with the governor in January 2018, he made it clear that this was to be an audio-only “oral” history. Because KQED needed broadcast-quality recordings for their podcast series, KQED assumed responsibility for that portion of the work.

The project team recognized that a great deal of preparation and background research were going to be essential for a successful oral history. OHC oral historians and KQED staff agreed to collaborate to develop an overview interview outline at the commencement of the project and then, as the project unfolded, interview outlines in advance of each interview session. This exchange helped the interviewers establish not only a shared agenda, but also a unique method in which two, three, and sometimes even four people were asking questions of the governor. Still, we recognized from early on that collaboration was key. While one interviewer might take the lead in one portion of the interview or another, overall the research and interviewing responsibilities were shared.

With a general plan in place, the final piece required was the formal agreement of the governor to participate in what we anticipated would be multiple recording sessions resulting in roughly a forty hour interview. In fall 2018, Shafer and Marzorati worked closely with Evan Westrup, then press secretary to the governor, to present our plan. With Brown’s tentative consent to participate, Shafer, Marzorati, Holmes and I met the governor in the historic mansion on what was one of his final days in office. The governor’s schedule was packed with nonstop exit interviews but he took the time to meet with us, during which we discovered that, while interested, he was not yet quite sold on the idea. He asked several tough questions about the process, our agenda, and the anticipated outcomes. He was keenly aware that his father had done a life history interview with OHC (then the Regional Oral History Office) which was released in 1982 — and he later told us that the existence of that oral history was key in his decision to participate in one himself. In the months leading up to the end of his term, Brown proved reluctant to discuss his “legacy,” but he ultimately agreed to do the oral history.

This oral history is appropriately the first interview of the newly relaunched California State Government Oral History Program. At the same time the Brown interview was in the planning stages, we were working with the Center for California Studies at Sacramento State, the California State Archives, and the California State Librarian to get the state legislature to renew funding for this program. The program first was established in 1985 with a vote of the state legislature. The law said, “The Secretary of State shall conduct under the administration of the State Archives a regular governmental history documentation program to provide through the use of oral history a continuing documentation of state policy development as reflected in California’s legislative and executive history.” The program was initiated in 1986 and in the ensuing decades scores of elected officials, appointees, and key government staff were interviewed. The program continued until 2003, when funding was pulled due to the state financial crisis that year and was not immediately restored when the state budget returned to balance. For the fiscal year 2018–2019 state budget, Alex Padilla, California Secretary of State, secured funds to relaunch the program administered by the State Archives. The reinvestment in the California State Government Oral History Program was essential in getting this interview completed and now available as a benefit to the public.

The formal interview sessions began on February 4, 2019, at the Mountain House III, Jerry Brown’s historic ranch in Colusa County, California, which is where all interview sessions would be recorded. A total of twenty interview sessions were conducted between February and October 2, 2019, when the final session was completed. Sessions ran between, roughly, ninety minutes and three hours; on some days two sessions were recorded, one in the morning and the other in the afternoon. Typically, the project team convened at the Mountain House on Monday mornings, interviewed throughout the day, and then spent the night in the nearby town of Williams; we would then record another one or two sessions on Tuesday before returning home that afternoon.

The original plans for the interview called for each main interviewer to focus on distinct chapters in the long biography. While this did take place to a certain degree, a variety of factors led to a more improvisational structure. Todd Holmes was set to play the lead role for OHC, while Shafer was to be the lead interviewer on the KQED team. However, in June 2019, Holmes was forced to attend to an ongoing family medical emergency, so his role, unfortunately, became more limited in subsequent sessions; while Holmes contributed significantly to the research and questioning in the first several sessions, and continued to make important contributions to background research, he was unable to attend a number of interview sessions in which he was to play a lead role. When Holmes had to step away, fortunately Shafer was able and willing to fill in any gaps. My planned role as interviewer for this project was to focus on certain specific issues such as Brown’s engagement with new ideas and unconventional thinkers, his fiscal policies and approaches to taxation, his years relatively out of the spotlight between 1983 and 1998, and then his terms as Mayor of Oakland and California Attorney General. Shafer thus became the lead interviewer for this project, asking the majority of questions, pushing the governor on issues from election strategy to his relationship with singer Linda Rondstadt. Shafer brought his in-depth and on-the-ground knowledge of California politics, particularly of the players, the issues, and the trends to this project. Although working largely behind the scenes, the role of Guy Marzorati deserves attention: alongside myself and Holmes, Marzorati contributed greatly to the extensive research dossiers and interview outlines that guided this project. He also conducted numerous background interviews with Brown associates which both informed our questions as well as contributed to the KQED podcast series (we anticipate including these interviews in the OHC collection at a later date). Readers of the transcript will also see occasional contributions from Marzorati as well as Queena Kim and Evan Westrup. I also want to acknowledge the good fortune of having Miriam Pawel’s then-just published group biography of the Brown family, The Browns of California (2018), as a key resource.

The KQED team uploaded digital audio files for each interview session and those were shared with OHC. OHC then oversaw the transcription of each interview session. Draft transcripts were edited by myself and Todd Holmes. When editing the transcript, we kept the governor’s words unchanged in most every instance, making only minor edits to fix errors or improve clarity if our task was clear. We did edit the transcripts in two more substantive ways: first, the governor would sometimes appear to finish a response at which point a question would be asked, but then he resumed his original answer; this created a number of unnecessary disjunctures in the transcript which were easily resolved with the removal of the out-of-place questions (which were subsequently asked, usually verbatim). The second substantive edits came with removing “off the record” content or other extraneous conversation: the KQED audio engineer would begin the recordings prior to the official beginning of the interview and thus captured some material that was not intended for public release, so this was cut; similarly, the interview was sometimes interrupted by external sounds (phones ringing, dogs barking, guests arriving), so these were deleted from the final transcript as well.

Edited transcripts then were provided to the governor for review and to approve. Evan Westrup took the lead on ensuring the timely and thorough review of these transcripts. The governor made very few edits throughout the roughly 800 pages of transcripts. OHC staff then prepared a final transcript, which entailed entering Brown’s edits, preparing a discursive table of contents, and assembling the additional material included in this document. Former Governor Gray Davis, who served as Brown’s chief of staff between 1975 and 1981, generously contributed a thoughtful and thorough Foreword to this oral history. Shortly after the release of this transcript, it will be cataloged and archived by The Bancroft Library. It is available on the website of the Oral History Center and the University of California Berkeley’s online library catalog. We anticipate by late spring 2020, the complete audio recordings of the interview (edited to conform to the lightly edited transcript) will be available for users to listen to on the OHC website. Moreover, the recordings will be synchronized with the transcript to enable users to search full text content in this time-based media. All of the oral history materials (recordings and transcripts) will be deposited with the California State Archives and available to users through their website as well.

Considerations of the Interview

A question often heard by oral historians is: what is the difference between journalism and oral history? It is not the easiest question, but there are a few points upon which there is some agreement. Oral history interviews are, by definition, recorded, preserved, and made accessible, in some fashion and at some date, to the public — to researchers who may wish to quote from the interviews and from other researchers who want to confirm the use and context of those quotes. Many oral historians provide the interviewee, or the “narrator,” the opportunity to review the interview (recording and/or transcript) prior to its deposit in an archive or release to the public. This arrangement allows for candor in an often long-format interview because the narrator knows she or he will be able to edit, seal, or otherwise prevent material from public release. This is not standard operating procedure for journalists. Although simplifying the matter, journalists let those whom they are interviewing know if the conversation is “on the record” or “off the record;” rarely are interviewees given the opportunity to review and change quotes made “on the record.” This posed a challenge to the project team at the onset, but an easy compromise was made early on: the governor would in fact be given the opportunity to review and correct the final transcript, but everything on the recording that was deemed “on the record” would stay “on the record” and thus would be available for KQED to use in their podcast production. This created the potential for tricky moments down the road if the governor made substantial edits or embargoed portions of his interview. Fortunately, Brown is experienced, to say the least, with media engagement and understood that everything recorded was the on record. While he chose his words carefully, electing to discuss some issues obliquely or not at all, he remained engaged, thoughtful, and largely candid throughout the long interview process.

One additional way in which oral history methodology and radio journalism ran up against each other is the issue of silence. Oral historians are taught time and again to allow potentially awkward silence to happen in an interview. We are told: don’t immediately jump to a new question after the narrator finishes their response. As a void, silence likes to be filled and it is often productive to allow the narrator to fill that silence. Something new, unique, or thoughtful might be added. I’ve used this technique many times and it does tend to produce results. Silence for radio journalists, however, is the enemy: questions are asked quickly to keep the audience engaged and the interviewee talking and, perhaps, a little off balance. Moreover, this oral history featured two and often three interviewers. As a result, Jerry Brown’s oral history was in some ways more like a lengthy but still rapid-fire radio interview than the kind of collaborative and slowly-paced interviews oral historians typically create. So this interview, this transcript is very much a hybrid document that resides at the boundaries of radio journalism and oral history.

As much as the circumstances of this project proved unique for oral history, the narrator himself was far out of the ordinary as well. We are fortunate to have a nearly forty-hour interview providing ample evidence of the uniqueness of this subject, but I’ll venture a few observations here. Jerry Brown, I found, to be a man with a largely unwavering set of core values and principles who sometimes appears to choose contradictory ways in which to express those drives. I am not the first to observe his belief in the value of frugality and in the virtue of austerity. And sure enough, these twin strands are woven throughout this story, from entering the seminary, to refusing the usual trappings of office when he became governor (such as limousines), to even rejecting (and vetoing) his own party’s budget when he considered it profligate. Brown recognizes at a profound level that we live in a world with limits and therefore it is virtuous to learn to live with those limits, making the most of the precious resources, opportunities, and time that we have. There is a very neat intersection then between his Catholicism and his interest in and real engagement with Zen Buddhism, which came to a real meeting point in Japan in the 1980s when he met with Father Lassalle, Jesuit, and Yamada Roshi, a Zen Buddhist leader. At the same time, points that might be considered contradictions appear in his narrative. For example, Brown himself has expressed great distrust of major social institutions. I think the long-running distrust between Brown and the faculty and administration of the University of California system comes down to the former’s skepticism about the value and fear of the doctrinaire aspects of formal education (along with his suspicion that university professors fail to appreciate the value of austerity). Why then would a man so critical of large social institutions spend his life seeking to lead them? Brown offers answers to this critical question throughout the oral history. Perhaps most important among these is that Brown seems truly comfortable inhabiting these apparent contradictions.

I have conducted hundreds of oral histories, but engaging with Jerry Brown was a new experience for me. Partly this was due to the fact that there were often three interviewers in the room; partly it was Jerry Brown himself. As a lifelong politician, Brown has ample reason to be suspicious of journalists and, based on his wrangling with professors, he feels largely ambivalent about academics as well. So while Brown already knew Scott Shafer and he knew of the Oral History Center through his father’s interview, the interviewing team was still regarded as “the journalists and the academics.” As will be evident when reading the interview, Brown sees journalists as reducers and simplifiers while academics are mired in their concepts and jargon; neither group has a great track record of explaining the world — especially the world of politics as it really is. For example, in session eleven, I made the observation to the governor, “You certainly had a domestic policy through line in your first two terms of governor.” He responds quickly and dismissively, “Wait, let me just back up to your through line—that’s another one of your metaphors.” Yet, then proceeds to offer a very thoughtful answer of the question. This type of interplay marked the entire interview process: sometimes it was productive and interesting, while at other times it became a little trying. But I think all recognized that this was the way in which Brown has always thought and engaged with others, friend and foe alike: not satisfied with pablum or fuzzy thinking, vigorous discussion and pointed debate were necessary to push any project forward. That spirit certainly reigned in this oral history interview.

Contributions of this Oral History

The purpose of oral history interviews is to create, preserve, and make accessible first-person accounts of lived history. Although Oral History Center staff regularly offer interpretations and analyses of their interviews, the prime goal in this center is to create documents (recordings and transcripts) that are not beholden to a single historian’s research objectives but rather attempt to seek information and ideas on a wide range of topics relevant to their narrator’s interests and expertise. To the extent that this is possible, we like to project and consider things that future generations might be interested in, and then ask our narrators to respond. So, any consideration of the contributions of a single oral history will be limited knowing its likely contributions today.