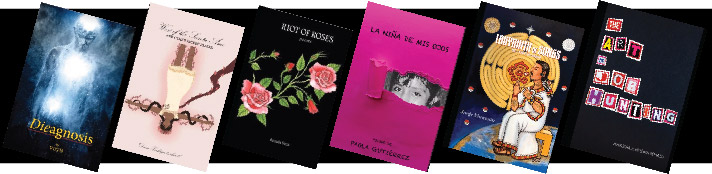

D.T. Robbins founded Rejection Letters Press in 2020. The idea for the press initially grew out of a joke about publishing fictional rejection letters after receiving a bevy of all-too-real letters.[1] Now, in 2025, the press has a selection of a phenomenal photographs and poetry online (see featured image above, captured in December 2025) as well as seven beautiful volumes of poetry and novels.[2]

While this Southern California press is not bound to a specific city, they host literary events in Los Angeles. Alongside book and poetry readings, the House hosts an annual “Rejection Week.” For this second event, their advertisements warned that there was “so much rejection, there [was] blood in the water.”[3] Readers can find out more about their events on their Instagram page.

Books at UC Berkeley Library

More at UC Berkeley Library

You can find access to what we have at UC Berkeley Library through a publisher focus using the US Library Search.

Notes

[1] “About,” Rejection Letters, March 3, 2020, https://rejection-letters.com/about/.

[2] “Rejection Letters,” Asterism Books, accessed December 8, 2025, https://asterismbooks.com/publisher/rejection-letters.

[3] Rejection Week 2025, August 25, 2025, Poster, https://www.instagram.com/rejectionlit/.