Bancroft Library

Summer Institute Alumni Spotlight: Alex Vassar

As interviewed by Todd Holmes

Alex Vassar attend our Advanced Oral History Summer Institute in 2017. A seasoned civil servant, Alex is no stranger to the circles of California government. In 2007, he served as a Senate Fellow in the state’s upper house, and worked thereafter in both houses before transferring to other departments of state government. Currently, he is the Communications Manager of the California State Library. When he joined us last summer, he had just finished an oral history of former State Senator Denise Ducheny on behalf of the State Archives. This interview was part of a collaborative effort between the State Archives, State Library, Sacramento State, and UC Berkeley’s Oral History Center to revamp the California State Government Oral History Program. That long effort ultimately proved successful, as the program was refunded in the 2018-19 state budget. We caught up with Alex this past month at his office in Sacramento to this victory and see what else he’s been up to since last summer.

Q: Tell us a little bit about your work and how you use oral history.

Vassar: I have always been interested in the political process and how the experiences of the people who run for office impact their thinking and decisions. That was a large part of why I moved to Sacramento in 2007 to participate in the Senate Fellows Program at Sacramento State. In the years since, I have conducted a number of short interviews with current and former state legislators. These interviews formed the crux of my recent book, California Lawmaker: The Men and Women of the California Legislature.

In 2016, I had the opportunity to sit down with former State Senator Denise Moreno Ducheny for a 14-hour interview. This was part of the State Government Oral History Program, housed at the California State Archives since the 1980s. I loved the long format of the oral history interview, spaced between multiple sessions, and how it allowed the interviewee to tell stories and take the time to explore memories.

Q: How did the Summer Institute shape your work?

Vassar: In 2017, I accepted a new role at the California State Library, heading up the Communications Division. Almost immediately after starting the new job, I had the opportunity to participate in the Oral History Center’s Advanced Summer Institute, thanks to the support of State Librarian Greg Lucas. It was an amazing experience and I loved the speakers, my classmates, and the campus. (My mother was working on a Ph.D. at Cal when I was born, but I had never spent more than a few hours on campus.) The Summer Institute gave me new insight into the practice of oral history, knowledge I’m hoping to bring to new interviews in the future, and more importantly, to the oral history-based initiatives we have created at the State Library.

Q: Tell us about these initiatives and what’s next on the horizon for your work in oral history?

Vassar: Recently, I’ve worked with State Librarian Greg Lucas and State Archivist Nancy Lenoil, as well as institutional partners such as the UC Berkeley’s Oral History Center and the Center for California Studies at Sacramento State, to restart the State Government Oral History Program. Created in the 1980s, the program had conducted hundreds of oral history interviews with former lawmakers and civil servants before funding was cut in 2003. My interview with Senator Ducheny was one of the few interviews conducted in recent years, thanks to the Center for California Studies at Sacramento State. I’m happy to report, however, that the efforts of the OHC and Sacramento State proved successful, with refunding of the State Government Oral History Program in the 2018-19 California budget. In addition to this program, we are also currently meeting with academic institutions to establish resources for oral historians to use and share at the State Library.

Curating Oral History in a Museum Setting

by Amanda Tewes

A few years back, I visited the Churchill War Rooms in London, the underground bunker near the Houses of Parliament from which Winston Churchill and his advisers directed British military efforts during World War II. My fellow museum goers and I followed the labyrinth of offices and bunkrooms – including Churchill’s personal quarters – to get a taste of what wartime life was like for Churchill, the war cabinet, and staff in this cramped space with no access to sunlight. These underground rooms were important to the security of the prime minister and his cabinet, as Nazi planes regularly rained down bombs on London during the war. While the physical layout of the Churchill War Rooms tells a compelling story about the difficult business of war, it is the many accompanying oral histories that provide texture to the subterranean world. For instance, former employees recalled feeling claustrophobic working so far underground, especially during air raids, while others spoke about taking their turn at the sunlamps that fought against Vitamin D deficiency. Hearing these personal stories in the space where these narrators lived and worked makes the museum about people and not solely wartime strategy.

Indeed, featuring oral histories in exhibits large and small makes big history personal. And sharing these stories in partnership with museums provides greater accessibility to collections for archives with limited public interaction. However, introducing oral histories into museum galleries raises a new set of challenges for both curators and oral historians.

One of these challenges is that of spacial design. How should the public engage with this oral history content: through a touch-screen video monitor, an audio-only listening station, or block quotes on the wall? In galleries where visitors expect to briefly browse images and short labels on the wall, how can curators entice them to stand still and watch/listen to several minutes of content? Curators may have to introduce oral histories at the earliest exhibition planning stages in order to best incorporate them into the space and the larger story.

Curators must also grapple with how to use oral history to question official narratives about a subject or event. Should these personal recollections compliment the exhibit’s narrative or challenge it? Further, sometimes oral history is the only way marginalized communities gain representation and historical acknowledgement in museum spaces. Therefore, what can curators do to not just feature oral histories, but also privilege the stories they reveal, particularly if these narratives do not exist in the museum’s artifact or image collections?

Finally, what is the responsibility of oral historians in developing content for museum exhibitions? Knowing that an oral history might become part of a museum exhibit, how should interviewers reframe these conversations? If museums need fresh content to tell their historical narratives, this provides opportunities for curators and oral historians to collaborate on projects that reveal new information or unique points of view.

Oral history practitioners should be asking not only what museums discuss, but also how they display it, and how oral history can affect these narratives. As an oral historian who formerly worked in a museum setting, these ideas were always on my mind when I pitched oral history content to curators. In our Summer Institute this August, I will be discussing these questions and conflicts with seasoned curators Erendina Delgadillo of the Oakland Museum of California; Christine Shook of the Wells Fargo Family History Center; and Margie Brown-Coronel of California State University, Fullerton. I look forward to exploring some of these questions with them and how they approach curating oral history. If you curate oral history or work in a museum setting, we’d love to hear how you think about these issues!

atewes@berkeley.edu

From the OHC Director, August 2018

by Martin Meeker

Since 2002, the Oral History Center has hosted a week-long advanced institute on oral history theory and methodology every August. We’ve welcomed over 500 people from across the country and around the globe, with another 30 about to join us this year. As my colleagues and I prepare for this year’s program, I wanted to reflect on where we’ve been and where we’d like to take this most worthwhile endeavor.

The first institute in which I participated was the second, in 2003. I had recently come to what was then known as the Regional Oral History Office, or ROHO, as a postdoc working with then-director Richard Candida-Smith. That first year (and, frankly, several that followed) are now nothing more than a blur: the experience was definitely one of those “drinking from a firehose” situations. Although I was soon to join ROHO as an interviewer, I now look back and see myself as a real oral history novice. I had read the requisite articles (Portelli!) and conducted a number of interviews, but my experiences were relatively few and not very diverse. The Summer Institute opened my eyes to many aspects of the interview that I had never really considered in any depth. I remember one session taught by guest faculty Jeff Friedman about movement and the performative aspects of oral history. Not that I needed any encouragement to feel more self-conscious in an interview setting, but this got me thinking more about the complexities of self-presentation, body language, and the dreaded yawn that sometimes escapes the mouth of an interviewer.

Subsequent years saw a number of interesting guest faculty appearances along with a revolving roster of OHC interviewers, but for the first dozen institute, the stalwart was Lisa Rubens, who curated and ran the institute. Lisa and I recently met for coffee and we discussed how the institute has changed in interesting and productive ways over the years, but one thing has been true since the beginning: the week is always invigorating (if exhausting) and one can always expect a slightly euphoric afterglow. With so many new relationships forged, so many opportunities to learn and share knowledge, the experience always is worth it.

On August 6th we’ll welcome our next group of summer institute participants. Shanna Farrell, who has led the institute since 2014, has planned what promises to be yet another always fascinating, and sometimes challenging, week of presentations, roundtables, and workshops. I’ll be presenting a updated version of my legal and ethics talk, which is inspired in part by my recent work on the committee revising the Oral History Associations documents on ethics and best practices. We are hosting another Tuesday evening presentation, free and open to the public. This year Erin Riggs will discuss the 1947 Partition Archive, which documents the troubled split of India and Pakistan. In addition to this, I’m especially looking forward to a panel on the final day of the event created by our two newest interviewers at OHC, Amanda Tewes and Roger Eardley-Pryor. They’ll not only discuss the performative aspects of oral history, they’ll…well, I don’t want to give away the surprise, do I?

Every year after the conclusion the institute, the faculty read very carefully the feedback provided by participants, and we take what they have to say seriously, often incorporating participant ideas into next year’s program. So, this institute has become a continuous learning experience for all of at OHC, which is what we hope it is for the participants too.

Martin Meeker

Charles B. Faulhaber Director

July 27, 2018

Where We’re Hanging Out: Saturday, August 11, 2018

by David Dunham

On Saturday August 11th, we’ll be in Richmond, California for the 2018 Rosie Rally 2018 Home Front Festival! at the Rosie the Riveter / World War II American Home Front National Historical Park. Join us!

This year’s annual event celebrates the spirit of Rosie the Riveter by encouraging dress in five costume categories: Best Traditional Rosie; Best Non-Rosie Home Front Worker; Best Parent/Child; Best Authentic 40’s Period Costume; or Most Creative Interpretation of Home Front History.

We look forward to seeing many of our past interviewees, including 96 year old Park Ranger Betty Reid Soskin, whose autobiography Sign My Name to Freedom was edited from her very own blog and our oral histories with her.

This past weekend we attended the Port Chicago Naval Magazine Memorial to honor those who passed on July 17, 1944 in the tragic explosion. Also in collaboration with NPS, we have conducted oral histories with survivors and others with connections to Port Chicago. Later this year we will be sharing online Dr. Robert Allen’s definitive audio oral histories and transcripts with members of the Port Chicago 50, the interviews that were the basis for his book The Port Chicago Mutiny.

This year the Friends of Port Chicago honored our dear NPS colleague Raphael Allen with the Port Chicago Commemorative Hero’s Award. Allen was a passionate storyteller, historian, researcher, and educator. His shoes can not be filled, but each of us whose lives he touched are inspired to work harder to tell the many important stories and lessons of Port Chicago and the World War II Home Front.

The Oral History Center has collaborated with the National Park Service on over 250 oral histories. Sign up for our eNewsletter for updates this fall when we update our website with enhanced search and a pilot of full video oral histories synced to the transcripts.

JOIN US on 8/7 for a Talk with Erin Riggs, Citizen Historian for the 1947 Partition Archives!

In Memory of Susan O’Hara

by Ann Lage

Susan O’Hara, our former colleague at OHC (back in ROHO days) and the prime mover in Bancroft’s acclaimed Disability Rights and Independent Living Movement (DRILM) project, passed away on July 1. We will remember her for her many fine personal qualities, among them a wonderful sense of humor, a gift for friendship, quiet yet strong leadership skills, and a keen historical sensibility. All of these came into play in bringing DRILM into being.

Susan was a 1971 participant in a groundbreaking experiment at Berkeley. A decade earlier UC Berkeley had opened a floor in the campus hospital to house students with significant physical disabilities, most of them then confined to nursing homes or to their parents’ care with little hope of accessing higher education. Attending Cal at a time of free speech and anti-war movements, the students found their voices, reveled in the zeitgeist of the sixties and the freedom of motorized wheelchairs, and became politically active. Over the next decade they founded on campus one of the first programs for students with disabilities in the nation. They next turned their attention to the broader community, founding the Center for Independent Living, which became the model for similar organizations across the nation. A host of spin-off organizations for people with disabilities grew out of CIL; many of the primary leaders of the battle for the Americans with Disabilities Act and other campaigns for disability rights and independent living came out of these initiatives. In 1975, Susan was hired as Berkeley’s coordinator of the residence program for students with disabilities, assisting students in the transition to independent living as the campus made residence halls accessible and closed down the Cowell Hospital unit.

In 1982 Susan approached Willa Baum, ROHO’s director, and made a compelling case that something of great historical moment had happened and was continuing to happen on campus and beyond. “This has got to be documented,” she urged. Willa immediately agreed and the long struggle to find funding for an oral history project ensued. It was difficult going. Susan and Willa’s understanding was ahead of their times; the Society for Disability Studies was just then coming into being, as a section of the Western Social Studies Association; the Disability History Association was far in the future. The Americans with Disabilities Act did not pass until 1990. Only a very few historians or social scientists recognized disability studies as a fruitful field of study and there were apparently no oral history projects underway. The NEH turned down the ROHO grant application three times, and we did no better with other grantors, although Willa was able to find a modest sum from Cal’s Prytanean alumnae to fund two pilot interviews.

Susan did not give up. By the mid-1990s, the time was right. Susan was alerted to a new program at the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research in the Department of Education that might be interested in our project. Susan and Mary Lou Breslin, another disability advocate with a strong sense of history, joined with ROHO to convince Bancroft Library curators of the project’s value. Their meeting resulted in a successful 3-year grant for an oral history program focusing on California leaders and behind-the-scenes activists, and including an additional component for Bancroft to acquire, preserve, and make accessible personal papers and records of activists and their organizations. Four years later, with a second NIDRR grant, the project moved nationwide, recording interviews and collecting historical papers of leaders of the movement in Massachusetts, New York, Washington DC, Texas, and other centers of activity.

Susan played a key role at every step as the project got underway. I was the project manager/coordinator for ROHO so I know better than most how important she was. Under the guise of her position as “historical consultant,” she advised on every aspect of the project. She helped us realize how important it would be to staff the project with interviewers from the disability community, who would have the trust of interviewees and organizational leaders whose memories and papers we were to collect. This trust was essential to study a movement with the watchwords “Nothing about us without us.” With her help, we hired an outstanding group of interviewers whose personal experiences, historical studies, and training in oral history methodology made them ideally suited to the project. Susan helped us navigate the difficult task of selecting interviewees, some of them recognized leaders and founders of organizations, some of them less well-known builders and sustainers of the movement or well-placed observers of key events.

Susan was a skilled interviewer; she conducted fourteen invaluable oral histories for the project. She was also a graceful writer and keen editor, who had a hand in all the project grant-writing, publicity, and website materials. Her lasting legacy in all these areas can be found on the project website at http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/collections/drilm/index.html. You will also find there a record of Susan’s many other contributions to the disability movement in her own oral history, Susan O’Hara, Director of UC Berkeley’s Disabled Students’ Program, 1988-1992; Coordinator of Residence Program for Disabled Students, 1975-1988.

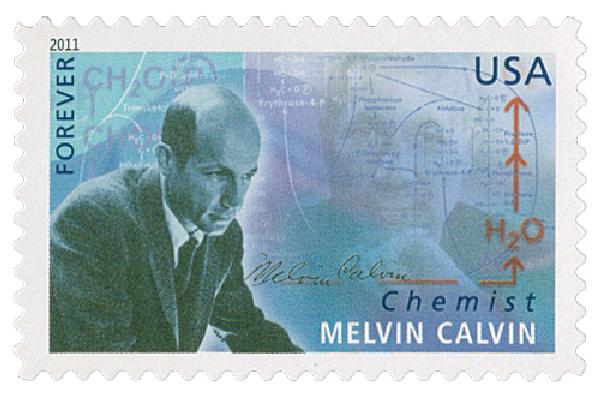

From the Archives: The Making of Mr. Photosynthesis

by Roger Eardley-Pryor In 1926, Melvin Calvin’s high school science teacher told him, “You’ll never make a scientist because you guess too much.” At the time, Calvin was an introverted, yet inquisitive, senior at Detroit Central High School. After skipping two grades in grammar school, he was younger and smaller than his classmates. Rather than nurse young Calvin’s curiosity, his science teacher scolded, “Be quiet. You don’t know what you’re talking about, you haven’t listened to the data.” But the precocious boy never stopped asking questions, and later, the data he produced made him famous.

In 1926, Melvin Calvin’s high school science teacher told him, “You’ll never make a scientist because you guess too much.” At the time, Calvin was an introverted, yet inquisitive, senior at Detroit Central High School. After skipping two grades in grammar school, he was younger and smaller than his classmates. Rather than nurse young Calvin’s curiosity, his science teacher scolded, “Be quiet. You don’t know what you’re talking about, you haven’t listened to the data.” But the precocious boy never stopped asking questions, and later, the data he produced made him famous.

“I tell you,” Calvin recalled in his oral history interview, “the instructor in physics really turned me off, not on. He was one of these people, [as] I remember him, who thought of science as the gathering of data and the drawing of conclusions. And guessing didn’t play any role in the development of science.” But, as Calvin remembered it, “I was a great guesser! He would ask questions and I would guess at the answers. I was wrong half the time,” Calvin admitted, “and he simply put me down.” Thirty-five years after those put-downs, TIME magazine named Melvin Calvin ‘Mr. Photosynthesis’ for his pioneering research unveiling the way plants wrangle sunlight, water, and air to make their food and, ultimately, power the planet. In 1961, Calvin’s search for answers to his endless questions earned him a Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

Melvin Calvin’s oral history interview addressed, in great detail, aspects of his renowned scientific career, from his postdoctoral work with Michael Polanyi in England, to joining Berkeley’s College of Chemistry in 1937, through his efforts in the Manhattan Project, to his pioneering research on photosynthesis. But the power of Calvin’s oral history resides in the unexpected, unscientific, and personal stories that appear nowhere else. Oral histories with scientists like Melvin Calvin reveal the human and emotional side to scientific processes that, from the outside, might appear purely rational or apolitical. Much of Calvin’s oral history delved into the political and interpersonal aspects of his scientific career, including his Nobel-winning research on the biochemical pathways of plants. Yet Calvin’s earlier stories—those from before his professional life took root—shine a light on the making of Mr. Photosynthesis.

Calvin remembered the moment he decided to become a chemist. It was that same year of high school, from 1926 to 1927, and Calvin stood in the grocery store that his father strained to keep solvent. Calvin’s working-class family didn’t always make ends meet. The 1920s may have been “roaring” for some, but like today, a great and growing gap separated rich from poor. Calvin’s family was the latter. “He was struggling,” Calvin explained of his father, “and I worked in that store with him.” At the age of sixteen, Calvin recalled, “I looked around and I saw that everything in that store depended in some way on chemists, from the labels on the cans to the food inside, the ink, the paper, everything involved chemistry.” His father’s struggle for security shaped young Melvin Calvin. “I wasn’t going to do that,” he deduced. “I was going to have something that was interesting to do and would make me a living at the same time.” Like his high school teacher’s rebukes, Calvin wanted no guessing whether or not he’d have a job.

Chemistry would become Calvin’s career, but he craved more than mere science. Sports never suited him, so in high school, he joined the debate team, and he was “in the plays, you know, dramatic things. … We put on a ‘Midsummer Night’s Dream’ and I was [Nick] Bottom.” At that time, Calvin confessed, “I was round, you know … so I played Bottom for obvious reasons!” Bottom’s asinine metamorphosis brings comedy to Shakespeare’s play, but more fitting for Calvin, the part also attunes the audience to meaningful themes like the relationship between reality and imagination. Bottom’s down-to-earth character, more than any other in the play, delves deep into the forest where he transcends his working-class identity to experience nature’s magic, enchant a fairy queen, and return having had “a most rare vision … a dream, past the wit of man.” Calvin’s continual wonderment in nature’s mysteries eventually made him one of the world’s leading biochemists.

In an era that lamented growing gaps between the humanities and science, young Melvin Calvin built bridges. Upon completing high school at age 16, Calvin began engineering courses at the Michigan College of Mining and Technology on the state’s remote Upper Peninsula. “I knew my opportunities there were limited,” Calvin disclosed, “because it was what it was, an engineering school.” After his first two years there, his family’s faltering finances forced his return to Detroit. “By that time,” Calvin recalled, “I already began to realize I needed intellectual exploration … I needed some broadening.” In the evenings Calvin worked in a Detroit brass factory chemically testing metal tailings, and during the day he took classes. “After two years in engineering school I went to Wayne State [then Detroit City College] and I didn’t touch an engineering subject. I didn’t go near one. I took history and art and psychology … That was a deliberate choice.”

Calvin continued his “broadening” in both science and humanities while completing his degree at Michigan Tech, earning his PhD from the University of Minnesota, and completing a postdoctoral fellowship in Manchester, England. Inside the laboratory, Calvin analyzed radioactive elements with varied half-lives. But outside the laboratory, rather than read scientific literature, he “preferred books that had a long lifetime.” He read creative classics like Don Quixote, Anna Karenina, and War and Peace. “These were novels to live in,” he remembered fondly, “you don’t live in the technical literature.” While reading War and Peace, for example, “I didn’t go to work, I didn’t do anything for about 10 days, you know, I read that book. I just got up and read it, had my lunch and read it, had my dinner, went to sleep. … I didn’t go to work. I read the whole thing in one sitting. It didn’t help much in terms of time, but I can remember doing that. I lived in that thing. … [T]hat was a very powerful experience.”

The memories Calvin explored in his oral history interview inspired a realization his scientific publications never revealed. After bringing his curiosity and creativity to Berkeley’s College of Chemistry in 1937, Calvin’s research with radioactive particles in plants earned a Nobel Prize in 1961. More than a decade after that award, Calvin reflected on the high school science teacher who told him to stop asking so many questions. “The more I learn about science in the ensuing forty years, the more I realize that guessing is the really creative part of science. That the gathering of data and the drawing of conclusions is really a computer operation. The part of it that isn’t a computer operation is the really creative part, and that’s the guessing.” Melvin Calvin’s oral history interview shows the human side of science—how the elemental and the imaginative, in conjunction, advance our knowledge of nature. The memories and insights in Mr. Photosynthesis’s interview reveal how a scientist, and how science itself, can grow.

Melvin Calvin’s oral history interview was recorded over several sessions between October 1974 and March 1978, as part of a series dealing with the development of nuclear research at Berkeley. The Oral History Center recently digitized the printed transcript of Calvin’s interview, previously available only at the Bancroft Library. The Oral History Center and archivists at the Bancroft Library are currently working to digitize the reel-to-reel audio recording of Calvin’s interview.

What We’re Listening To

What I’m Listening To: Presidential Podcast

By Amanda Tewes

Chances are that if you remember anything about William Henry Harrison, the ninth President of the United States, it’s that he did not wear a coat to his inauguration on a bitterly cold day in 1841, caught pneumonia, and died a month into office, making his presidency the shortest in American history. Unfortunately, this memorable story about Harrison’s brief presidency is not true. His March 1841 inauguration day was not that cold, and modern physicians think that typhoid fever–thanks to a contaminated White House water supply–was the real culprit in laying Harrison low. So why have Americans perpetuated this myth about Harrison? This is just one of the many questions posed by Lillian Cunningham on the Presidential podcast, which she hosts.

Cunningham began Presidential, a forty-four episode (one for each president) podcast series, during the run-up to the 2016 presidential election, which critics felt was historically divisive, even during primary races. Drawing from her experiences writing about leadership for the Washington Post, Cunningham took a different approach to the election. She uses Presidential to explore each American president as a way to understand which character traits and historical circumstances made for effective leadership. In short, how do we define a successful presidency and why?

The series is a fresh take on not only American history, but also on modern American politics. Cunningham creates memorable narratives about each leader, humanizing even the “forgotten presidents.” In examining each president’s personality, she also asks guest historians what listeners would have been able to expect on a blind date with these men (pro tip: don’t let your friends set you up with James K. Polk!). This informative and witty approach makes Presidential a not-so-guilty pleasure.

Listening to this podcast two years after it aired is an odd experience. In many ways, Presidential captured the spirit of the 2016 election, but it is also a good reminder that no political outcome is inevitable. William Henry Harrison certainly did not foresee the untimely end to his month-long presidency.

As an oral historian, Presidential has me wondering: when do contemporary politics become history? This podcast has made me more aware than ever how, as an interviewer, I help shape narratives about the past. I will be thinking about my impact on oral history, from which questions I ask to how I ask them, as I conduct my interviews in the future.

Summer Institute Alumni Spotlight

Summer Institute Alum Spotlight: Julia Thomas

Julia Thomas attended our Advanced Oral History Summer Institute in 2016. When she joined us, she was studying history and environmental analysis at Scripps College. She’s now working as a freelance journalist, traveling the world to document grassroots media, as a Thomas J. Watson Fellow. We caught up with her recently to find out what she’s been up to since, and how oral history informs her work as a freelance journalist.

Q: Tell us a little bit about your work, and how you use oral history.

Thomas: I’m a freelance journalist, just beginning my work after studying history and environmental analysis at Scripps College. My current research is supported by a year-long Thomas J. Watson Fellowship, during which I’ve been learning about and documenting grassroots media from the ground up in Nepal, India, Zimbabwe, South Africa, Spain, and Ecuador. I’ve been spending time in the field, working alongside, and interviewing journalists as they report on current stories in progress and the methods they use to present people’s voices on a mix of platforms.

Oral history has played a major role in this project and I’m continually adjusting the ways I use it. Sometimes, and especially in my most recent work in South Africa, I’ve used oral history in more formalized interviews about the organizing and establishment of a community newspaper under Apartheid, the housing crisis in Durban and Cape Town, and community radio practices. At other times, I’ve engaged with oral history as it’s being produced in the moment, in the form of podcasts and radio, by journalists in-country.

Throughout this project, one of my hopes is to incorporate oral history sensibilities into any conversation I have, regardless of whether the recorder is on, or the topic is related to journalism. Oral history requires slower and more deliberate attention to questions to allow people to open up and share. I’ve sought to use oral history as a means of understanding new places and explore its possibilities. How far can the discipline of oral history stretch? What recitations of sound fall under its umbrella? I’ve developed a habit of recording the atmosphere of places, such as buses or streets, and protests or songs performed at community gatherings. I do this both as a means to viscerally return later and capture the sounds around every day movement and life. I believe that this is oral history in a way, too, and that preservation of how an environment sounds unprompted – who is allowed to be heard or what kind of voices dominate – is just as important as difficult questions posed in conversation.

Playing with oral history in conjunction with understanding journalists’ work and how best to preserve it, is a lot of fun and a consistent challenge. The questions stay the same for a while, perhaps shaped by current happenings in place, and then they change drastically depending especially, of course, on lingual context and whether or not I can understand or communicate. Much of the time, I haven’t been able to do interviews in the first language of vernacular language journalists, so the practice of oral history becomes dependent on recorded sound and my own observations of context.

This then raises the question: how much can one truly translate or take away from such a listening experience? I am still figuring out how to present and connect the many stories this exploration has led to, but my hope is to create a collection of transcribed interviews, a podcast that brings community journalists focused on similar issues in different contexts into conversation, and a longer form written project that connects the media landscapes and current stories in the countries I’ve visited.

Q: What is the state of the project that you workshopped at the Summer Institute?

Thomas: The project I workshopped eventually grew into my undergraduate thesis, which traced the use of buses as a space in social movements throughout the twentieth century in Mexico and the United States. It also became a condensed long form piece, published in the Los Angeles Review of Books, that examined contemporary examples of buses as a site of protest and state control – such as phenomena of “busing” protestors in the wake of the 2016 election and attendance at the 2017 presidential inauguration as measured by number of bus permits secured. Both of these projects are more literature heavy than I anticipated when I went to the Summer Institute, largely because my workshop group helped me to think about this research on buses as a larger and longer term focus than what I could have accomplished in an single undergraduate academic year. My workshop group very much influenced my thinking about positionally, potential angles, and people to interview. Funnily enough, I am actually answering these Q&A questions while riding on a bus in Spain!

Q: What kinds of oral history techniques do you use in your work as a journalist?

Thomas: Whenever possible, I try to think about interviews as opportunities for oral histories and ask questions that bring out a longer history beyond the topic at hand. My hope is to make interviewees comfortable enough to open up in sharing their own stories. When I’m doing an interview in a journalistic capacity, I try ask more open-ended questions and step back rather than steering the interview according to a particular angle for a story. Staying focused on the individual narrative, rather than thinking of them as a certain voice that will speak a particular perspective, is a technique I always try to use. In journalism, it can be easy to ask questions oriented around a certain topic and shut off the opportunity to go deeper into someone’s story, but oral history makes you step back, take more time, and see each conversation as an opportunity.

Something I’ve started to ask people is, what kind of story would you like to tell or feel should be told about your situation, this particular movement, etc.? Oral history gives agency and power back to the person sharing stories from memory, in their own words and lived experiences. It also inherently requires more of an emphasis on context and an individual’s position within the issue being discussed, which journalism can always use more of. I try to think about my interviews as oral histories a chance to gain a deeper understanding about situational context as much as possible.

Q: How did the Summer Institute shape your work?

Thomas: Attending the Summer Institute was a very inspiring experience for me, particularly as an undergraduate student with a strong interest in oral history but no formal training in its methodologies. I developed a lot of new ideas and gained eye opening insights from fellow attendees. The people in our 2016 cohort came from such a wide variety of places and this in and of itself was exciting to see how academics, journalists, architects, activists, policy makers, teachers, were curious about using oral history in their unique applications. I learned a great deal about the logistics of carrying out an oral history projects as a freelancer though the mock interviews and techniques that were presented. At the time of the Institute, I was actually preparing my application for the Watson Fellowship and had a general idea of my project but couldn’t quite articulate what it was that I wanted to explore. On one of the last days of the Institute, it became clear to me that the practice of asking questions and capturing people’s voices is what really fascinated me. I remember it suddenly clicking in my head after a few days of being immersed in discussions of oral history that I knew this was what I wanted to learn more about in other parts of the world.

Q: How do you hope to grow your work in the future?

Thomas: I’m planning to spend the next couple of years working as a freelancer, and hope that the year following this fellowship will be spent writing long-form feature pieces about what I encountered in each place, and continue to report (hopefully abroad!). I’d love to return to the topic of buses and do some oral histories with transport unions and workers, activists, organizers of solidarity caravans, etc., particularly in Mexico. This year has also piqued my interest in radio programming and podcasting, so I’d love to break into that. Some broad topics of interest as of right now are individual experiences and social movements related to elections, land and housing rights, and music composition and performance. Graduate school of some sort is definitely in the future at some point, but until then, my hope is to keep learning, interviewing, experimenting, collaborating. We’ll see what happens from there!

For more from Julia, follow her on Twitter: @juliathomas317 and Instagram: @jthom317

From the Archives: Sauntering in the Sierra

Sauntering in the Sierra

by Roger Eardley-Pryor, PhD

@Roger_E_P

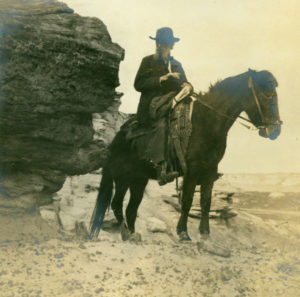

Deep into Sequoia National Park, a thin, wiry rider climbed a mountain trail atop a dusty white horse. He wore a dark business suit, per his backcountry custom, and from under his black felt hat, a bushy white beard spilled forth. Up the Kern River Canyon, a group of young Sierra Club members trekked through the high country. As the rider approached them, his piercing blue eyes surveyed the group from under his shadowy hat.

“Where are you going?” the rider inquired.

“We’re just hiking in to camp,” the hikers replied.

“Hiking is a vile word,” the rider returned. “You are going right past one the finest views in the Sierra. Now stop and look at it.”

It was the summer of 1908, and the young Sierra Club members heeded his command. For they knew the thin, dark rider was John Muir, famed mountaineer and co-founder of the Sierra Club.

“You know,” Muir said, “when the pilgrims were going from England to the Holy Land, the French would ask them ‘Where are you going?’ They did not speak French very well, but they would say ‘Santa Terre’ (Holy Land). That is where we get our word ‘saunter.’ And you should saunter through the Sierra, because this is a holy land, if ever there was one.”

When John Muir preached this parable of wilderness-appreciation in 1908, he left an indelible mark in the mind of C. Nelson Hackett, who recalled the encounter in a 1972 oral history interview. Hackett was born in the City of Napa in 1888. He joined the Sierra Club during high school and later earned degrees from the University of California, Berkeley and Harvard Law School. After a stint in the U.S. Army, Hackett worked at the Bank of California (now MUFG Union Bank) where he became vice president and headed its trust department. When interviewed at eighty-three years old, Hackett recalled, “I don’t know of anything in my life that has been more delightful than those Sierra Club outings.” In 1908, during Hackett’s outing, Sierra Club membership had just reached 1000. Today, with three million members and supporters, Sierra Club is the largest and most influential grassroots environmental organization in the United States.

Hackett’s memory of Muir comes from Sierra Club Reminiscences II, 1900s-1960s, part of the Oral History Center’s extensive collection of interviews with Sierra Club leaders and longtime members. The roots of the Oral History Center’s relationship with the Sierra Club stems, in part, from a chance encounter on a long bus trip from San Francisco north to the dedication of the newly established Redwood National Park in August 1969. On that bus trip, Phillip Berry, then recently elected as the Sierra Club’s youngest president, sat next to Amelia Fry, an oral historian from the Bancroft Library. Fry had interviewed former National Park Service directors Horrace M. Albright and Newton Drury, and many others associated with natural resources and politics. While riding to Redwood National Park, Fry convinced Berry about the value of preserving the Sierra Club’s unwritten stories through oral history interviews. In May 1970, the club’s board of directors authorized the Sierra Club History Committee, which partnered with the Oral History Center to begin recording reminiscences of longtime club members in 1971. This interview series continued until the mid-2000s, during which the Oral History Center collected nearly one hundred Sierra Club interviews with former presidents and directors, including Ansel Adams, Edgar Wayburn (two interviews), David Brower (two interviews), Michael McCloskey (two interviews), and Carl Pope. Funding challenges brought a halt to the project, but the Sierra Club oral histories remain available online and preserved at The Bancroft Library. Today, the Oral History Center is planning to revive the series in conjunction with the club’s William E. Colby Memorial Library.

If you want to donate to this important project , please contact oral history interviewer Roger Eardley-Pryor at rogerep@berkeley.edu.