Digital Collections Unit

530K Primary Resources Now Available Online through The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement: A Digital Archive

The Bancroft Library has recently completed the digitization of nearly 150,000 items related to the confinement of Japanese Americans during World War II as part of a two-year effort to select, prepare, and digitize these primary source records as part of a grant supported by the National Park Service’s Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant Program. This program helps to support the preservation and interpretation of U.S. confinement sites where Japanese Americans were detained during World War II. This recent project, The Japanese American Internment Sites: A Digital Archive, represents our fourth grant from this program, which together have culminated in over 530,000 primary resource materials being made available online.

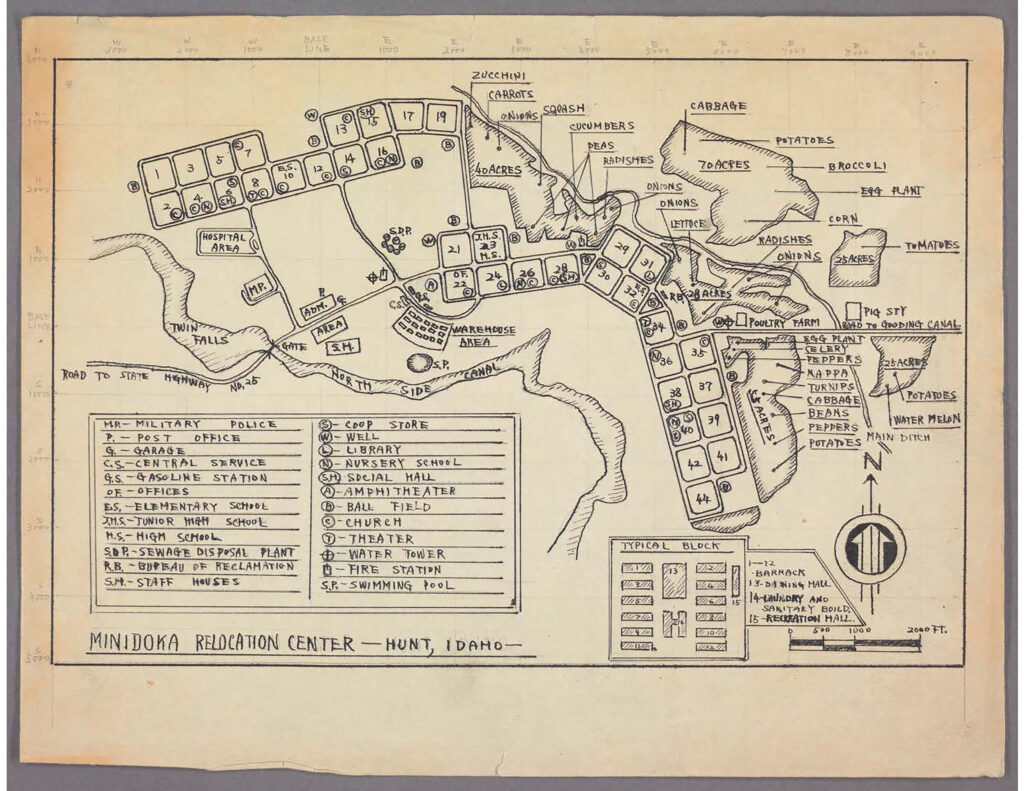

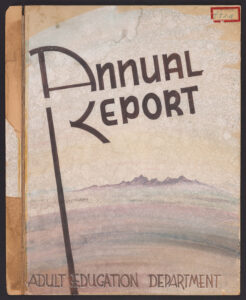

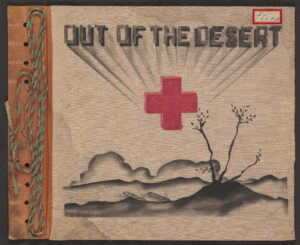

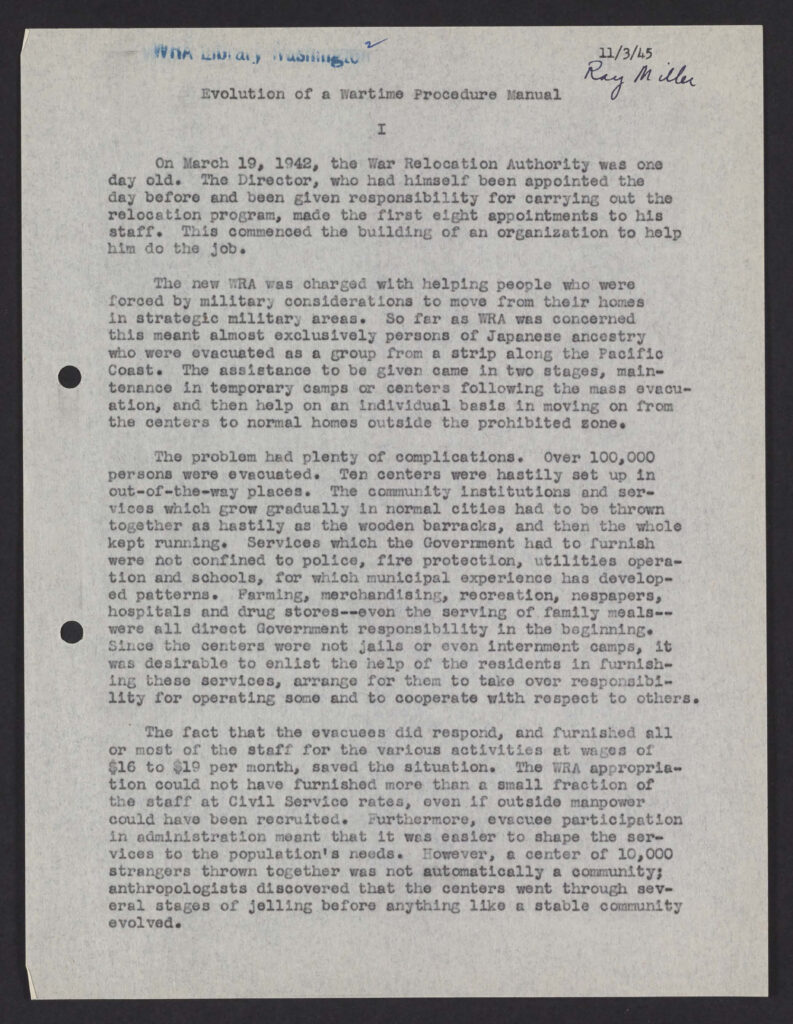

The project focused on the U.S. War Relocation Authority (WRA) files from the Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Records (BANC MSS 67/14 c). The WRA was created in 1942 to assume jurisdiction over the incarceration of Japanese Americans during the war. Between 1942-1946, the agency managed the relocation centers, administered an extensive resettlement program, and oversaw the details of the registration and segregation programs. These newly digitized records from the Washington Office headquarters and the district, field, and regional offices, formally document WRA management of internment of Japanese Americans in “relocation” centers and resettlement of approved individuals under supervision in the eastern states. Digitized materials document the registration of individuals; disturbances such as strikes; policies and attitudes; daily life in the camps including educational and employment programs; correspondences and other writings by evacuees; Japanese American service in the armed forces; and public opinion.

Since 2011, the Bancroft has been awarded four grants from the National Park Service’s Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant Program. The previous grants have digitized records from the Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study and archival collections selected from individual internee’s personal papers, photographs, maps, artworks, and audiovisual materials. The Bancroft’s Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement: A Digital Archive website (http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/collections/jacs) brings together all the digitized content and the recently published LibGuide (https://guides.lible.berkeley.edu/internment) that explains how to use and access these collection resources.

As we now embark on our recently awarded fifth grant from this program, we look forward to bringing even more collections online to support researcher access. We are honored and grateful to be able to make these important resources available to help interpret this period in American history and to preserve them for future generations.

The project was led by digital project archivist Lucy Hernandez and principal investigator Mary Elings, Assistant Director of Bancroft and Head of Technical Services. Special thanks to Julie Musson, digital collections archivist at Bancroft and Jennafer Prongos, BackStage Library Works technician for their work on this project, as well as support from Theresa Salazar, Bancroft curator of Western Americana. Many thanks to the Library Information Technology group at the University Library for their work in managing the files, maintaining the information systems used in the project, and ensuring the publication and long term preservation of the digitized collections through our partnership with the California Digital Library.

————

This project was funded, in part, by a grant from the U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant Program. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Department of the Interior.

Dr. Robert Allen’s Port Chicago and Civil Rights Archive and Oral History Collection

By Julie Musson and Lisa Monhoff

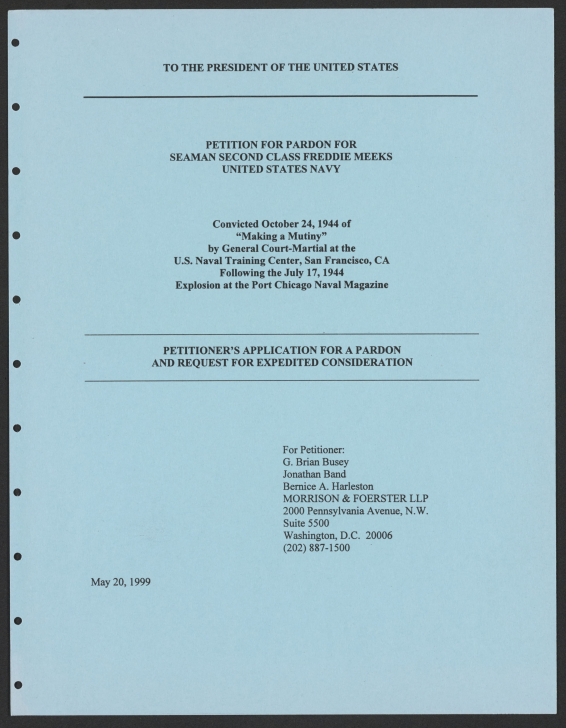

This July marks the 75th Anniversary of the Port Chicago Naval Magazine disaster, a massive explosion that resulted in the largest loss of life on the U.S. mainland during WWII. The explosion happened while African-American sailors were loading a munitions ship in the Suisun Bay. Munitions detonated and two cargo ships exploded killing 320 and injuring 390 sailors and civilians. After the explosion, hundreds of African-American servicemen refused to return to segregated, unfair, and unsafe work conditions and 50 of those sailors held out for better work conditions. In response, the Navy charged the men with mutiny and sentenced them to 15 years of hard labor. The disastrous event at Port Chicago and media coverage of the ensuing mutiny trial was a pivotal moment in the discussions of racial inequality in the U.S. and contributed to desegregation in the Navy beginning in 1946.

In 2016, the Port Chicago Naval Magazine National Memorial under the stewardship of the National Park Service acquired the Dr. Robert Allen Port Chicago and Civil Rights Collection. The collections comprised of 35 linear feet of research archives and 34 hours of oral history interview content produced by Dr. Robert L. Allen as the result of over 40 years of primary research, documentation and scholarly works. The work of Dr. Allen to understand and publicize the disaster and the mistreatment of the sailors culminated in the publication of The Port Chicago Mutiny in 1989 and has continued with decades of appeals for official pardons and exoneration for those charged with mutiny.

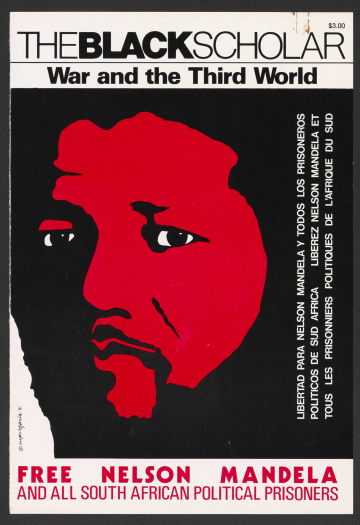

The Robert L. Allen papers on Civil Rights consist of correspondence, primary research, writing and teaching materials created by Dr. Allen in his capacity as activist, editor, writer and educator. Dr. Allen’s body of work includes several books written and published about civil rights and labor leaders, including Bay Area activists Lee Brown and C.L. Dellums. He also served as Senior Editor and writer for many years at The Black Scholar, co-founded a small press with Alice Walker called Wild Trees and taught in the Ethnic Studies and African-American Studies programs at the University of California, Berkeley.

In collaboration with the National Park Service, the Bancroft Technical Services processed and digitized the National Park Service’s Dr. Robert Allen Port Chicago papers and the Bancroft’s Robert L. Allen papers on Civil Rights. The Oral History Center digitized and transcribed the Port Chicago Oral History interviews.

Links to the resources are below.

The Bancroft’s Robert L. Allen papers http://www.oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8sq966g/

NPS Allen (Dr. Robert) Port Chicago Papers http://www.oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8f195h3/

Oral History Center Port Chicago Interviews http://www.lib.berkeley.edu/libraries/bancroft-library/oral-history-center/projects/poch

Now Available! The Japanese American Internment Sites: A Digital Archive

The Bancroft Library is pleased to announce the completion of the “Japanese American Internment Sites: A Digital Archive” which includes important historic materials from our archival holdings that are now available online.

The project was generously funded as part of the National Park Service’s Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant Program and includes approximately 150,000 original documents from the Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Records (BANC MSS 67/14 c). The records represent the official documentation of the U.S. War Relocation Authority. Existing from March 1942 to 1946, the WRA was created to assume jurisdiction over the relocation centers, administered an extensive resettlement program, and oversaw the details of the registration and segregation programs.

“We are very grateful to The National Park Service for funding the digitization of these important historical documents.” said Mary Elings, Assistant Director and Head of Technical Services at The Bancroft Library. “We hope researchers will find the content informative and that we will see new digital scholarship emerge as a result of this material now being available in digital form.”

The project builds upon two previous grants conducted between 2011-2017 to digitize 100,000 documents from the Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study and 150,000 original items from Bancroft’s archival collections including the personal papers of internees, correspondence, extensive photograph collections, maps, artworks and audiovisual materials. Together, these collections bring the total number of digitized and publicly available items to about 400,000 and form one of the premier sources of digital documentation on Japanese American Confinement found anywhere.

The Japanese American Evacuation & Resettlement Digital Archive website, http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/collections/jacs provides context to this rich and substantive digital archive, and directs users to collection guides on the Online Archive of California and curated searches of digitized objects on the Calisphere website.

—

This project was funded, in part, by a grant from the U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant Program. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Department of the Interior.

Voices in Confinement: A Digital Archive of Japanese American Internees

The Bancroft Library is pleased to announce the publication of the Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Digital Archive.

The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Digital Archive is the result of a two-year grant generously funded by the National Park Service as part of the Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant Program. The grant titled, “Voices in Confinement: A Digital Archive of Japanese American Internees”, includes approximately 150,000 original items including the personal papers of internees, correspondence, extensive photograph collections, maps, artworks and audiovisual materials.

Selected from Bancroft’s vast holdings, these rich and often requested collections were digitally captured as high-quality archival TIFFs for preservation. Access images were created as JPEG image files and text searchable PDF formats for optimal accessibility. The project website provides context to our comprehensive digital archive with pointers to collection guides on the Online Archive of California and curated searches of digitized objects on the Calisphere website.

The project builds upon a previous grant conducted between 2011-2014 to digitize 100,000 pages from the Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study. Together, these collections form one of the premier sources of digital documentation on Japanese American Confinement found anywhere.

View the Japanese American Evacuation & Resettlement Digital Archive Website: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/collections/jacs

This project was funded, in part, by a grant from the U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant Program. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Department of the Interior.

All In Time

by Sonia Kahn from the Bancroft Digital Collections Unit.

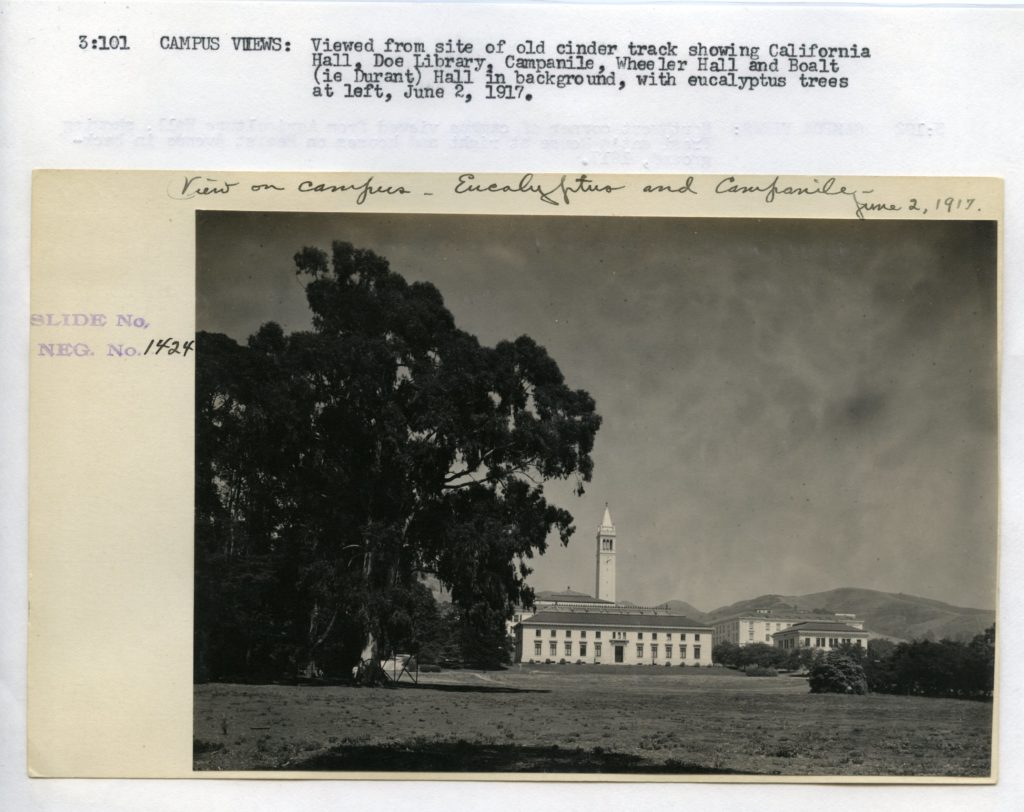

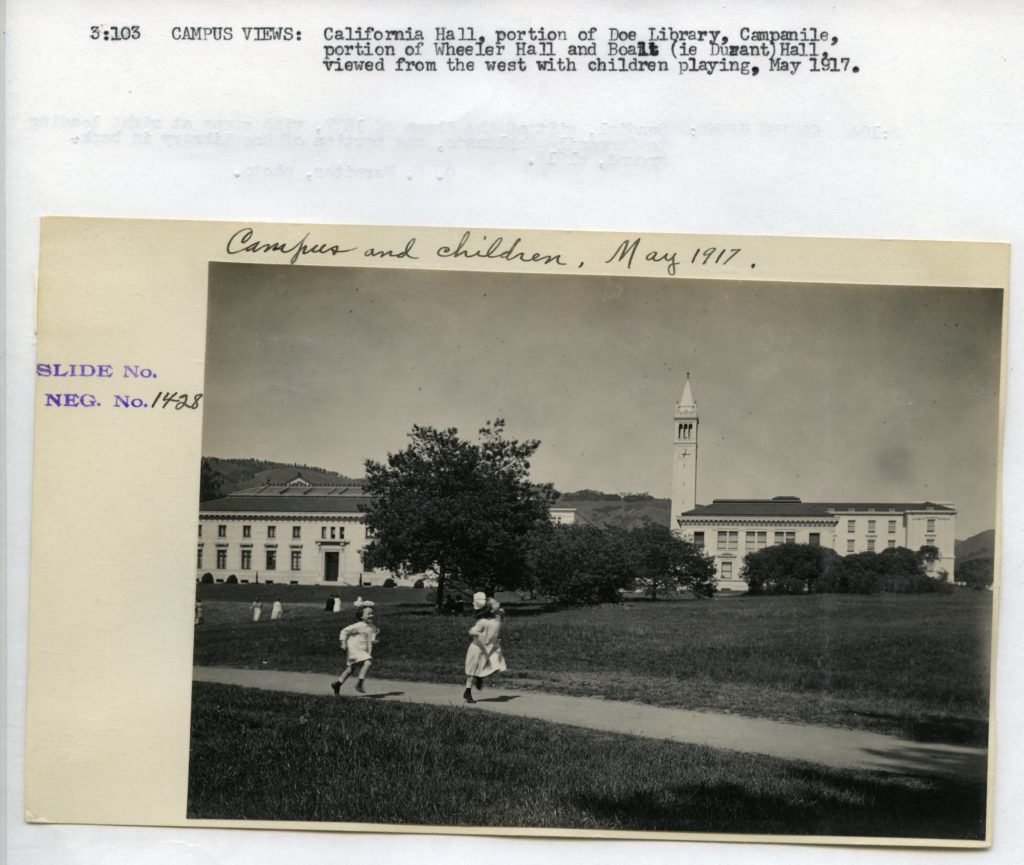

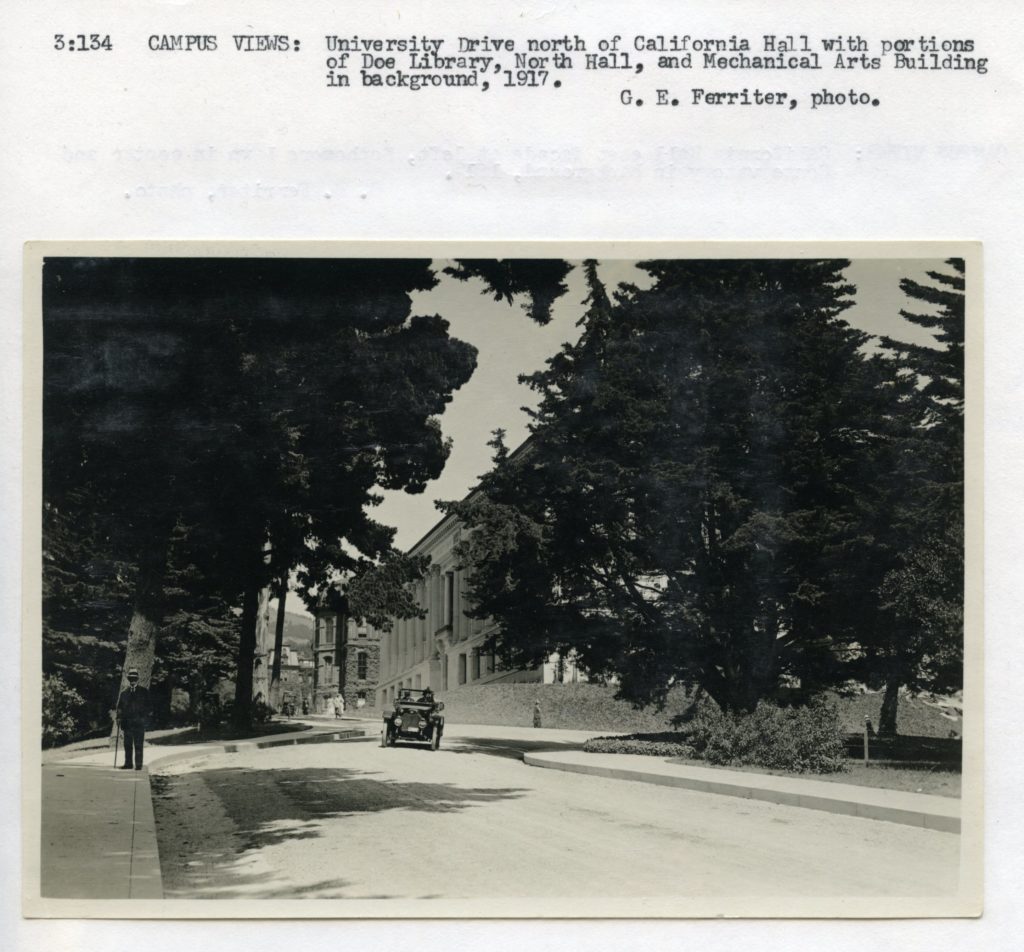

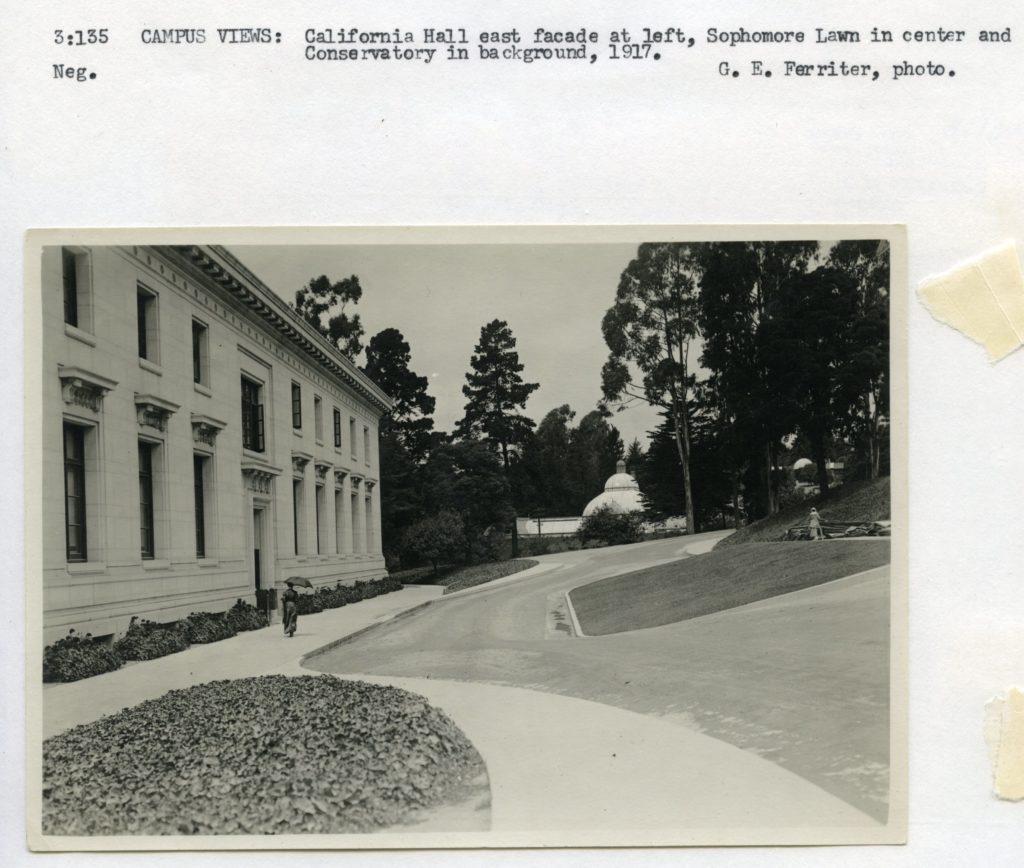

As another school year comes to a close, and the class of 2017 has walked through Sproul Plaza for the last time, now feels like the perfect opportunity to take a step back from the fury of finals and reflect. With the stresses of contemporary life – constant messages and emails to reply to, the morning commute, trying to precariously balance family and friends with work and play – it can be easy to get lost in a vortex of stress and responsibilities. But at times like these, when pressure becomes so prevalent, it is worth pausing to admire what surrounds us. Pardon the cliché, but it really is worth stopping to smell the flowers. So many of us pass through Sather Gate every day in a rush to get to class, but how often does one stop to truly appreciate the Gate, or the Campanile, or even just the lush greenery of the campus?

As a senior who has just graduated and is about to enter a new (and stressful!) phase of life, I thought it would be worth doing exactly that. In the quiet before the storm I decided that as one of my final blogs for the Bancroft, it might be nice to make a tribute to the campus, both for my sanity, and out of respect for the school that has been my home for the last four years. So in late spring, as the pressure mounted, I made my own effort to step back, further than most. Instead of admiring the campus merely in the here and now, I wanted to explore what had changed, and by the same token, what had stayed the same. The Bancroft houses the University Archives in which I found bits and pieces of what I was looking for. Photographs of the campus from as early as the 19th century. There were so many fantastic pictures in the collection – from a horse and carriage trotting along with South Hall, and her long forgotten sister North Hall, clearly visible in the background, to photos of a typewriter shop on Telegraph Avenue with old time 1950s cars parked out front. But I decided as a member of the class of 2017 that I would focus on the view of campus from a century ago, taken while the world was at war in 1917. After settling on this, I went out and retook some of the pictures we have from 1917 to find out exactly what had withered away and what had stayed in the hundred years since they were first taken.

I hope that in looking at these comparison shots, more people might be able to pause and collect their thoughts, even for just a few minutes, while reflecting on the beauty of the campus that we often take for granted. When we’re so caught up in the moment, taking notice of something like Sather Gate, which has stood in place for more than 100 years, might be our cue to relax. There are buildings and trees that have been here for generations. Manmade structures and nature alike have transcended time, and the Sather Gate I walk under today is the same one two little girls posed next to in 1917. Our campus is beautiful, and it is worth remembering that these buildings will outlast our stresses, just as they have for all the Berkeley alum and employees that have come before us.

UARC PIC 03 3.100

UARC PIC 03 3.125

If you are interested in more photos of the Berkeley campus over the past two centuries please visit the Reading Room at the Bancroft Library.

Images are from the University of California, Berkeley campus views collection: http://oskicat.berkeley.edu/record=b16284958~S1

Arrival of the Mobe

by Sonia Kahn from the Bancroft Digital Collections Unit.

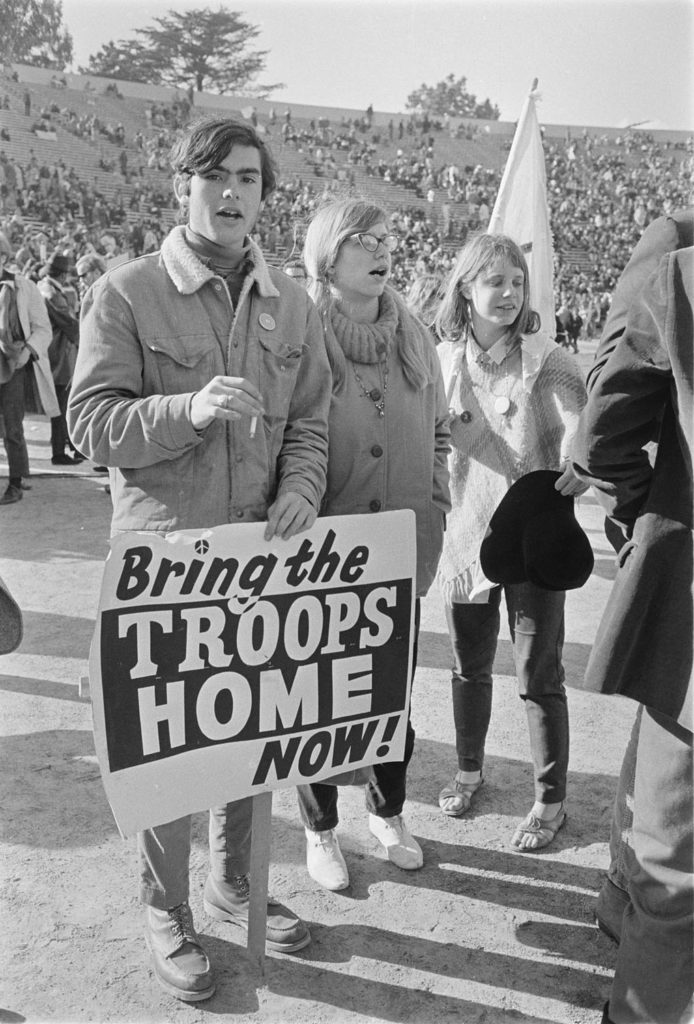

From coast to coast, April 15, 1967, was a busy day for American anti-war protesters. Fifty years ago today, massive demonstrations filled the streets of New York and San Francisco as marchers denounced US involvement in Vietnam.

[Michelle Vignes photograph archive, BANC PIC 2003.108–NEG Box 19, Roll 1752, Frame 22, Bancroft Library]

[Michelle Vignes photograph archive, BANC PIC 2003.108–NEG Box 19, Roll 1752, Frame 22, Bancroft Library]

The protests were organized by the Spring Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam, commonly referred to as “the Mobe,” which began in 1966 as a coalition of various groups opposed to the war. High profile names were among those who attended the marches, including Dr. Martin Luther King, who led the march in New York, and his wife Coretta King, who spoke to protesters at the counterpart demonstration in San Francisco. The Spring Mobilization protests were particularly noteworthy for the cooperation between civil rights and peace protesters in a greater effort to call for an end to the war.

The marches themselves were quite massive. In New York, upwards of 400,000 people joined the march which began in Central Park and was slated to end at the United Nations where speakers, including Dr. King, addressed the crowd. The demonstration in San Francisco, while smaller, still drew in between 75,000-100,000 protesters who walked from Second and Market Streets to Kezar Stadium in Golden Gate Park. There, demonstrators were similarly treated to speeches by Coretta King as well as actor Robert Vaughn.

In Central Park, before the East Coast march got underway, there was a mass burning of draft cards. Protesters claimed to have burned nearly 200 draft cards, although this number was never verified.

Though the protests were peaceful, there were a few notable skirmishes. In New York, some demonstrators were bombarded by eggs thrown out the windows of various apartments on Lexington Avenue. Others were struck by red paint launched outside of police barricades on the march route. In Times Square, fights also broke out between motorists stalled by heavy traffic and demonstrators taking part in the march.

In both cities, counter-demonstrators popped up to voice their support of the war. In New York, pro-war protesters carrying American flags and signs ran on the sidewalks beside the protesters and heckled them. In San Francisco, a group of about 50 war supporters brought up the rear of the march into Kezar Stadium, also carrying signs with slogans like “Support Our Men in Vietnam” and “Communism is Red Fascism.” The group circled the track amidst loud booing from the anti-war demonstrators until they were escorted out of the stadium.

Fifty years later America still prides itself on the First Amendment which protects our right to freely speak and assemble. This year has already proved a strong one for protest, making its mark with the Women’s March in January. The demonstration was a shot heard round the world, when half a million demonstrators marched on Washington, and another 100,000 filled the streets of Downtown Oakland. The size was roughly on par with the anti-war demonstrations of a half century ago. Considering our present day advancements with social media to help get the word out, this makes the numbers of those who showed up to voice their anti-war beliefs in 1967 all the more impressive. But despite the differences, what the similarities between these two huge movements prove is that the American tradition of protest is still vibrant, 50 years on.

Onwards to No Man’s Land

by Sonia Kahn from the Bancroft Digital Collections Unit.

One-hundred years ago today, on April 6, 1917, the House of Representatives voted 373 to 50 formally authorizing the United States’ declaration of war against Germany. As a direct result, the US joined its allies Britain, France, and Russia in the war to end all wars. More than 116,000 American soldiers would lose their lives in a war that many thought was Europe’s problem. The Battle of Argonne Forest alone would cost more than 26,000 American lives, making it the deadliest single battle in American history. The conflict would end up being the third bloodiest in US history, with only the Civil War and Second World War producing more military deaths.

World War One had ignited in a frenzy in the summer of 1914, but for almost three years the United States had managed to keep itself out of the Great War. That’s not to say that the US felt no impact from the conflict. The sinking of the British liner Lusitania by a German U-boat in May 1915, for example, resulted in the deaths of 128 American passengers onboard and tensed US-German relations.

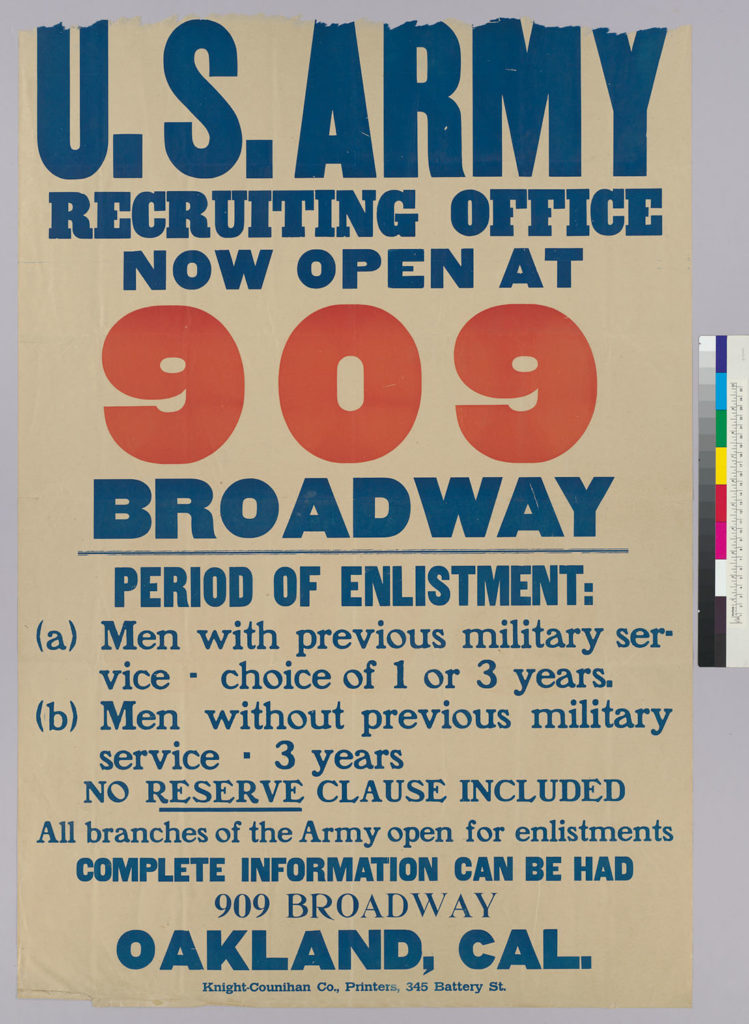

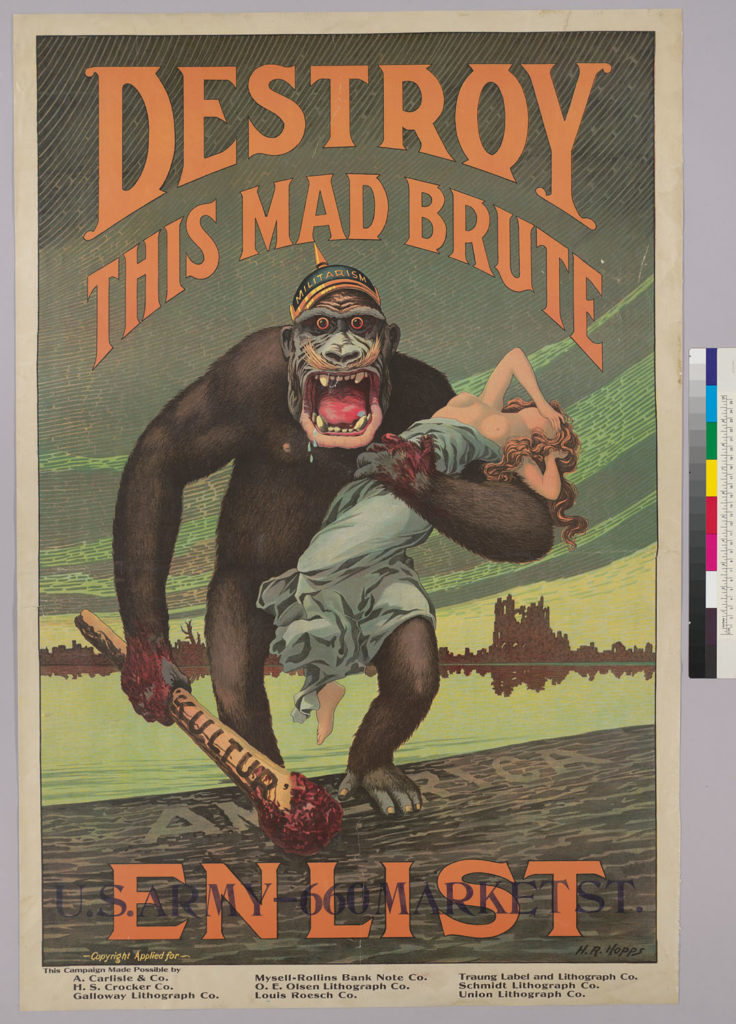

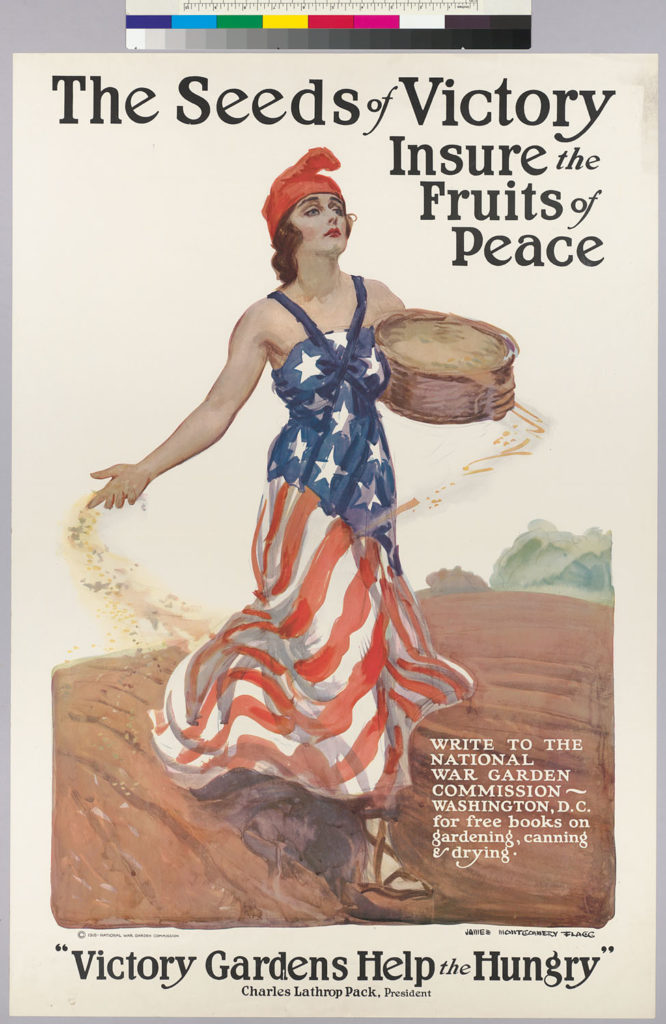

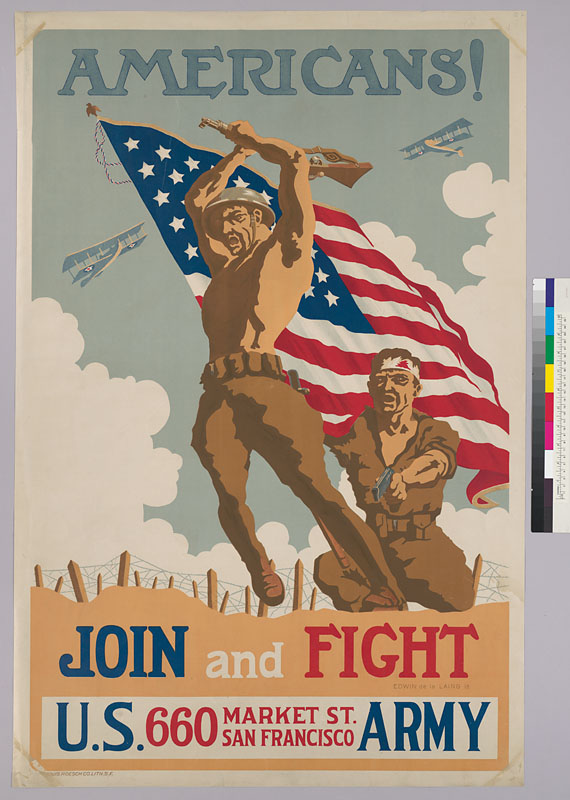

On April 6, America joined the fight against the Kaiser’s troops. But much was needed to fight a war. Soldiers, food, supplies, had to be acquired. To get Americans on board with the war effort the government produced a variety of propagandist war posters encouraging everything from the obvious signing up to join the armed forces, and buying war bonds, to urging women to join the Red Cross. Though the US homefront was not terribly affected by the conflict, some posters even encouraged women to plant Victory Gardens, almost as an eerie foretelling of what would come in the Second World War.

The Bancroft Library houses a collection of more than 170 American war posters from the First World War. Some of these posters have addresses for army recruiting stations in San Francisco and Oakland, a reminder that a piece of a worldwide conflict played out in our backyard.

View the digitized collection here: American war posters from the First World War [BANC PIC 2005.001]

Incalculable Odds: The story of how one professor (unintentionally) wound up at UC Berkeley

by Sonia Kahn from the Bancroft Digital Collections Unit.

Berkeley is known for its world-renowned professors. Just walking through the campus today you can spot parking spaces reserved for Nobel laureates. Of course, this is hardly a new phenomenon at Berkeley, which has had prominent faculty on its staff for decades. Perhaps one of the most distinguished members to grace the Berkeley faculty, and one with a fascinating history to boot, was a professor in the mathematics department named Alfred Tarski.

In 1918, Tarski began his academic career, entering the University of Warsaw. He studied mathematics under prominent logicians and philosophers of the time. In 1924, Tarski graduated with a Ph.D., becoming the youngest person to obtain a doctorate from the University of Warsaw. Between 1924 and 1939, Tarski worked intermittent positions at the University of Warsaw, but mostly made a living by teaching math to secondary school students. This was actually a common practice in Europe prior to the Second World War as university positions tended to pay poorly. Meanwhile, as he taught the basics to teenagers, he wrote various papers and books, earning himself an international reputation as a mathematical logician and for his ideas on truth, which the current writer will not attempt to summarize here because they are well beyond her.

In 1939 Tarski was invited to attend the Unity of Science Congress in September, held at Harvard University. In August 1939, Tarski boarded a ship bound for the United States. It would be the last ship to leave Poland before Nazi forces invaded the country on September 1, igniting World War Two. He left behind a wife and two children in Warsaw who he would not see again until 1946.

Effectively exiled in the US, Tarski worked at various research institutions including Harvard, before settling on the world’s best research university: UC Berkeley. In 1942 he joined Berkeley’s mathematics department, and was eventually tenured in 1945 before being awarded a full professorship in 1948. In 1946 his wife and two children, who had all survived the devastation of the war, joined Tarski in California.

Tarski stayed on at Berkeley, helping to create an esteemed graduate program in logic, until 1968 when he retired, becoming a professor emeritus. However, he remained devoted to Berkeley and students even in retirement, continuing to teach until 1973, and supervising doctoral theses until his death in 1983.

Today the Bancroft Library maintains a collection of materials relating to Tarski’s tenure as a mathematician at UC Berkeley. Among them are personal documents of Tarski’s, from his Polish passport, to a dinner menu saved from his sailing voyage to the US in 1939.

Digital reproductions of selected items are available: Alfred Tarski papers (BANC MSS 84/69 c)

A Truly Perilous Journey

by Sonia Kahn from the Bancroft Digital Collections Unit.

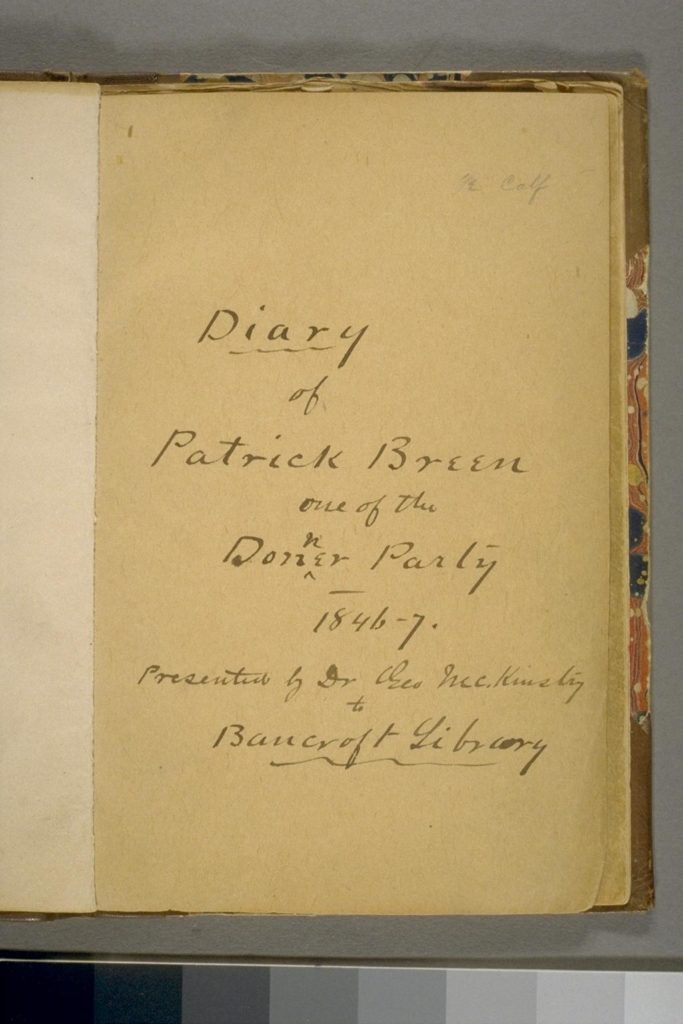

“We pray the God of mercy to deliver us from our present Calamity if it be his Holy will,” wrote Patrick Breen on New Year’s Day 1847. In the midst of a snow storm, with provisions running short and several members of his party already dead from starvation, Calamity was not an overstatement.

Breen was a member of the now infamous Donner Party. An Irish immigrant, he had set out with his wife and seven children to make their way westward from Illinois to the California sunshine. The Breens composed just one family in the group of 87 people to make the trek led by George Donner and James Reed. Only 48 would survive the ordeal.

Calamity struck the Donner Party while in the Sierra Nevadas. Stuck in the first blizzard of the season, the party was unable to continue the journey. The blizzard, unfortunately, was not a quick setback but the harbinger of a terrible winter to come.

Patrick Breen began recording in his diary on November 20, 1846. “It continueing [SIC] to snow all the time we were here we now have killed most part of our cattle having to stay here untill [SIC] next spring & live on poor beef without bread or salt,” wrote Breen. “Poor beef” would hardly seem such a terrible meal when a few weeks later the party had resorted to eating animal hides. The situation deteriorated even further, and as members of the party perished, Breen described how other members thought about, or claimed to have engaged in, cannibalism. When one woman mentioned that she was considering consuming a dead comrade out of desperation, Breen quite simply wrote “It is distressing.” Such bare simplicity perfectly describes the feeling one is faced with in reading the trials of the Donner Party.

On February 19, 1847 the first rescue party arrived bringing a few provisions. The relief team of men from California took with them 21 members of the party, but the Breen family was left behind. 170 years ago today, on March 1, 1847, Breen made the last entry in his diary which recounts the arrival of the second relief team. This second rescue team guided 14 people, including the Breen family, to safety in Sutter’s Fort, California. A third relief team later rescued all the remaining children of the Donner Party but was forced to leave behind five stragglers. By the time the fourth team arrived, only one man was still alive.

The history of the Donner Party and the epics detailed in Breen’s diary are a reminder of the lengths to which people once went to reach this golden state, and the sunny days we often take for granted.

The Bancroft Library maintains the original Breen diary and has digitized the journal.

View the collection: Patrick Breen Diary (BANC MSS C-E 176)

Why American Concentration Camps Became Legal (and Then Illegal)

by Jacob Dickerman from the Bancroft Digital Collections Unit.

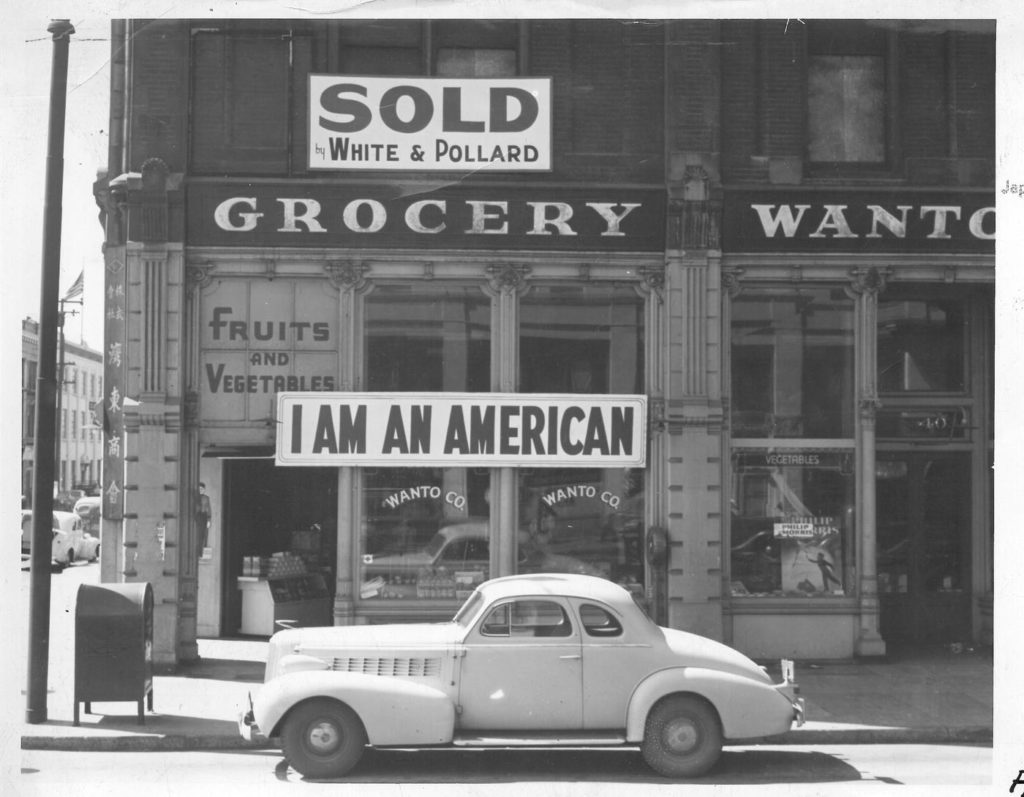

76 years ago, on December 7, the Japanese military attacked Pearl Harbor military base. The next day, the United States declared war against Japan. Following the attacks and declaration of war, hostilities were high, as many Americans vilified and mistrusted their fellow Japanese American citizens. Of course, the vilification and mistrust were unfounded.

Two months before the attack on Pearl Harbor, the “Munson Report,” an intelligence report commissioned by the State Department, concluded that there was no question of loyalty to the U.S. among the majority of Japanese Americans and that they posed no threat to the nation’s security. Despite such exculpatory reports and a lack of cause for suspicion or detainment, the FBI, as soon as December 7, 1941, began arresting Japanese American community leaders, totaling 1,291 arrests in just two days.

Today, this seems unfathomable, but hostility toward Japanese Americans had been a long-established and prominent issue, socially and politically. On October 11, 1906, the San Francisco–San Francisco–Board of Education passed a measure to segregate children of Chinese, Japanese, and Korean descent from the rest of the student population. (President Theodore Roosevelt called the measure “wicked absurdity.”) In 1908, Japan and the U.S. made a “Gentlemen’s Agreement” to end migration of Japanese laborers to the U.S. In 1913, California passed the Alien Land Law, prohibiting those ineligible for citizenship from owning (and, later, leasing) land; at the time, all Japanese immigrants were considered ineligible for citizenship.

As it turned out, the draconian laws against Japanese immigrants, who mainly labored in agriculture, were neither followed nor enforced too heavily. Unfortunately, the relative leniency drew resentment from labor unions, statewide, as the population of Japanese Americans steadily increased. This intensified the presence and influence of anti-immigrant interests and politicians in government, contributing to the height of tensions when Pearl Harbor was attacked.

On February 19, 1942, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which authorized military authorities to exclude civilians from any area, without trial or hearing. This was effectively aimed at Japanese Americans on the West Coast. In March of that year, the Wartime Civil Control Administration established the first Assembly Centers (detainment camps, or “concentration camps,” in FDR’s words), where they detained about 92,000 persons of Japanese ancestry. The count would eventually increase to 120,000 persons, when the permanent camps were established by the War Relocation Authority, in May 1942.

In January of 1943, the War Department announced the formation of a segregated unit of Japanese American soldiers. Soon after, on February 1, the 442nd Regimental Combat Team was activated at Camp Shelby, Mississippi. During seizures, arrests, and the unconstitutional detainment of tens of thousands of Japanese Americans, thousands were wounded, killed, or went missing in action while serving the nation in the 442nd RCT. Though President Obama awarded the Congressional Gold Medal to Japanese-American World War II veterans, in 2010, the nation failed to express appreciation to the same Japanese Americans during the war.

A year after forming the 442nd RCT, the U.S. reversed its policy on excluding Japanese Americans from the draft and reinstated it, requiring men in the internment camps to serve. Hundreds refused to serve in the same military that oversaw the indefinite incarceration of their friends and families. Most of these men were imprisoned for resisting the draft. In 1947, President Truman pardoned 63 draft resisters imprisoned in 1944. The 63 were detainees at Heart Mountain, a concentration camp in Wyoming, who organized an effort to challenge the legality of their detainment by refusing to show for their physical examinations.

The last camp left, Tule Lake “Segregation Center,” closed on March 20, 1946. Though the Truman administration sent a friendlier message to Japanese Americans, the nation was slow to learn from the crimes committed against its own citizens. Only in 1980 did Congress formally begin to question the constitutionality of Executive Order 9066, that which granted the military the liberty to take liberties away from other Americans.

Commenting on the possibility of the government’s legally detaining Americans without due process, the late Justice Antonin Scalia said, “You are kidding yourself if you think the same thing would not happen again.” The nation should prove him wrong.

The Bancroft Library maintains a collection of over 7000 photographs from the War Relocation Authority.

View the collection: War Relocation Authority Photographs of Japanese-American Evacuation and Resettlement (BANC PIC 1967.014–PIC)