by Jacob Dickerman from the Bancroft Digital Collections Unit.

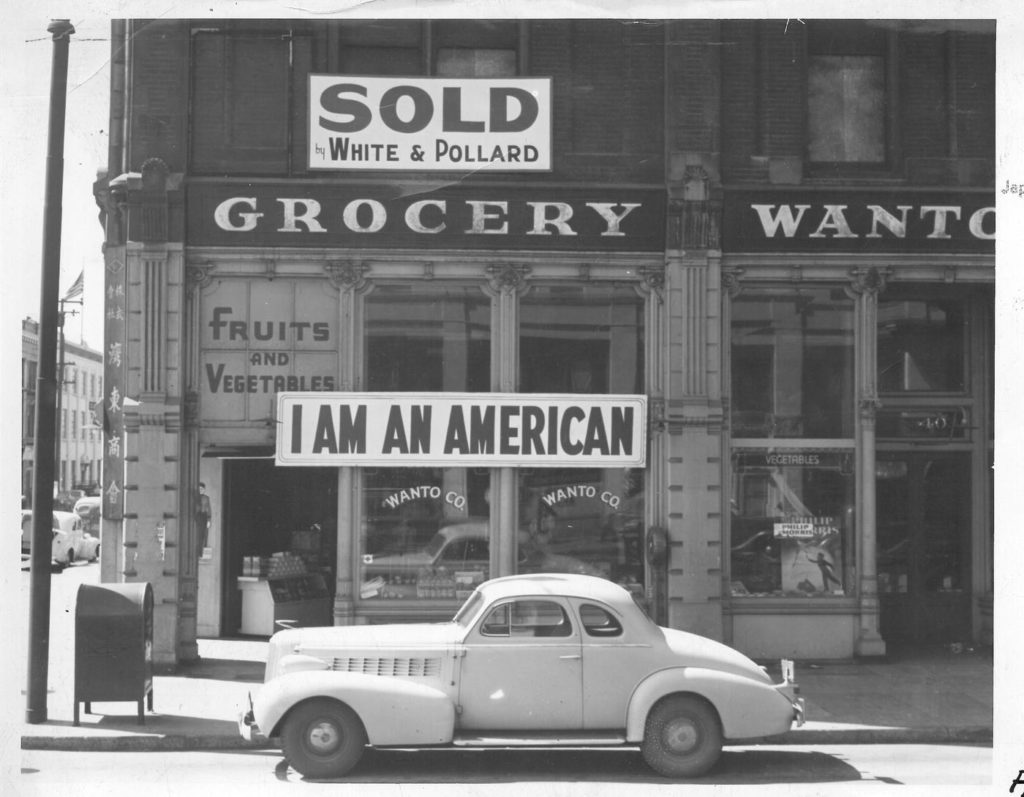

76 years ago, on December 7, the Japanese military attacked Pearl Harbor military base. The next day, the United States declared war against Japan. Following the attacks and declaration of war, hostilities were high, as many Americans vilified and mistrusted their fellow Japanese American citizens. Of course, the vilification and mistrust were unfounded.

Two months before the attack on Pearl Harbor, the “Munson Report,” an intelligence report commissioned by the State Department, concluded that there was no question of loyalty to the U.S. among the majority of Japanese Americans and that they posed no threat to the nation’s security. Despite such exculpatory reports and a lack of cause for suspicion or detainment, the FBI, as soon as December 7, 1941, began arresting Japanese American community leaders, totaling 1,291 arrests in just two days.

Today, this seems unfathomable, but hostility toward Japanese Americans had been a long-established and prominent issue, socially and politically. On October 11, 1906, the San Francisco–San Francisco–Board of Education passed a measure to segregate children of Chinese, Japanese, and Korean descent from the rest of the student population. (President Theodore Roosevelt called the measure “wicked absurdity.”) In 1908, Japan and the U.S. made a “Gentlemen’s Agreement” to end migration of Japanese laborers to the U.S. In 1913, California passed the Alien Land Law, prohibiting those ineligible for citizenship from owning (and, later, leasing) land; at the time, all Japanese immigrants were considered ineligible for citizenship.

As it turned out, the draconian laws against Japanese immigrants, who mainly labored in agriculture, were neither followed nor enforced too heavily. Unfortunately, the relative leniency drew resentment from labor unions, statewide, as the population of Japanese Americans steadily increased. This intensified the presence and influence of anti-immigrant interests and politicians in government, contributing to the height of tensions when Pearl Harbor was attacked.

On February 19, 1942, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which authorized military authorities to exclude civilians from any area, without trial or hearing. This was effectively aimed at Japanese Americans on the West Coast. In March of that year, the Wartime Civil Control Administration established the first Assembly Centers (detainment camps, or “concentration camps,” in FDR’s words), where they detained about 92,000 persons of Japanese ancestry. The count would eventually increase to 120,000 persons, when the permanent camps were established by the War Relocation Authority, in May 1942.

In January of 1943, the War Department announced the formation of a segregated unit of Japanese American soldiers. Soon after, on February 1, the 442nd Regimental Combat Team was activated at Camp Shelby, Mississippi. During seizures, arrests, and the unconstitutional detainment of tens of thousands of Japanese Americans, thousands were wounded, killed, or went missing in action while serving the nation in the 442nd RCT. Though President Obama awarded the Congressional Gold Medal to Japanese-American World War II veterans, in 2010, the nation failed to express appreciation to the same Japanese Americans during the war.

A year after forming the 442nd RCT, the U.S. reversed its policy on excluding Japanese Americans from the draft and reinstated it, requiring men in the internment camps to serve. Hundreds refused to serve in the same military that oversaw the indefinite incarceration of their friends and families. Most of these men were imprisoned for resisting the draft. In 1947, President Truman pardoned 63 draft resisters imprisoned in 1944. The 63 were detainees at Heart Mountain, a concentration camp in Wyoming, who organized an effort to challenge the legality of their detainment by refusing to show for their physical examinations.

The last camp left, Tule Lake “Segregation Center,” closed on March 20, 1946. Though the Truman administration sent a friendlier message to Japanese Americans, the nation was slow to learn from the crimes committed against its own citizens. Only in 1980 did Congress formally begin to question the constitutionality of Executive Order 9066, that which granted the military the liberty to take liberties away from other Americans.

Commenting on the possibility of the government’s legally detaining Americans without due process, the late Justice Antonin Scalia said, “You are kidding yourself if you think the same thing would not happen again.” The nation should prove him wrong.

The Bancroft Library maintains a collection of over 7000 photographs from the War Relocation Authority.

View the collection: War Relocation Authority Photographs of Japanese-American Evacuation and Resettlement (BANC PIC 1967.014–PIC)