Professor Henrike Lange’s recent book Eclipse and Revelation: Total Solar Eclipses in Science, History, Literature and the Arts has been released as an audio book read by Professor Chris Hallett.

Professor Henrike Lange’s recent book Eclipse and Revelation: Total Solar Eclipses in Science, History, Literature and the Arts has been released as an audio book read by Professor Chris Hallett.

By Willow Beyer, Undergraduate Library Making Fellow, 2024-2025

Over the course of my first semester as a Makerspace Fellow, I have had the opportunity to learn and grow beyond my new skills in crafting. I have watched and experienced the ways that art is not about just the finished product, the skills that go into creating it, or what it communicates; it’s about how its production affects the artist.

When visiting the Makerspace for the first time, many people comment on how calming the act of creating can be. Undergrads come here to work with their hands, take a breath outside of the academic demand of their day to day life, and help each other approach new problems. Sharing advice, working out the logistics of their ideas together, and showing off what they’ve been working on is an essential part of using the Makerspace. In the fiber arts room, it’s always fun to see the clothes people are making and think through the best way to accomplish their goals in a room full of people with varied sewing backgrounds. I love when people teach each other skills they learned that day, like using the Silhouette machine or button makers, because they get to not only solidify that knowledge for themselves, but meet someone new.

The Makerspace quietly works as a space for its users to decompress. Dedicating my service hours to creating has had a massive positive impact on my life. As Library Fellows, we work to create not just physical projects, but an intentional cohort where collaboration and feedback are valued and the methods through which they are carried out are clearly defined and respected. We work on a variety of shared projects, including workshop design and promotion and Make of the Month setup. Because we prioritize each other’s feedback, it’s much easier for me to share my ideas for my peers’ work and I feel more confident that I will get honest and helpful responses. By incorporating others’ insight into my Silhouette designs, stamps, and posters, I have been able to improve more quickly. By practicing articulating my thoughts on others’ work, I have improved in communication and solidified what I’m learning in design. Exposure to a community of intentional crafters and dedicated time for making has been helpful in alleviating stress and lifting my mood throughout the semester. While overwhelmed, spending an hour where my only job is to work on my knitting skills or to carve a stamp or make a Silhouette design helps to give me a break from the theory and abstract thought of my studies to work on something I can actually hold in my hands. I have found this experience very grounding, and can’t recommend enough that you stop by and see what the space can bring to your life!

By Madison Lee, Undergraduate Library Making Fellow, 2024-2025

At Berkeley, it’s easy to be swept up in the relentless pace of “hustle culture.” Lectures, exams, and extracurriculars often dominate every waking moment, leaving little time to breathe, let alone nurture one’s creative side. Amid this whirlwind, the Makerspace became an unexpected refuge—a space where I can pause, reset, and rediscover the joy of creating.

I’m grateful to have discovered the Makerspace during a Makerspace Crawl. Until that event, I had no idea it even existed. It’s a place that has allowed me to step away from the grind and reconnect with hands-on crafts and activities that have brought me a deep sense of calm and fulfillment. It rekindled a love for creating that I didn’t realize I had set aside. So I hope that more students will have the chance to also experience it.

This past semester as a Library Fellow in the Makerspace, has been a journey filled with learning, experimentation, and connection. One of my earliest experiences involved learning to thread and use a sewing machine just minutes before a student walked in, eager to learn how to sew. Together, we tackled those first stitches—initial panic giving way to laughter and discovery. That moment set the tone for the collaborative and shared learning experiences that would follow.

As I immersed myself in the Makerspace, I was continually amazed by the projects and passions I encountered. One of my favorite moments was helping a student 3D-print a miniature spider figure. Listening to them share their love for miniatures, I marveled at the dedication and detail they poured into their work. These glimpses into others’ creative worlds became a constant source of inspiration.

Throughout the semester, I’ve had the privilege of witnessing students grow in their craft. Watching someone’s confidence blossom is nothing short of magical. One student I taught to use the sewing machine began by practicing straight stitches on paper. Week by week, they returned, steadily improving their skills and eventually completing a beautiful handbag project. Others brought in ideas for buttons and T-shirts for their clubs, clothes for fashion shows, and even intricate cosplays and Halloween costumes. Each creation told a unique story, and I felt deeply honored to play a small part in their journeys.

The workshops were another highlight of my time. I enjoyed collaborating with the other Makerspace fellows to select workshop topics that would spark creativity and plan detailed outlines and instructions to ensure the projects were approachable for everyone. Working with students to complete their first projects—whether guiding them through using Silhouette software to cut vinyl stickers or helping them transfer designs onto rubber for stamp carving—was absolutely infectious. These experiences reminded me that making isn’t just about the finished product; it’s about the process. The trial and error, the learning curve, and those moments of triumph along the way are where the real magic happens.

Of course, there were challenges. I struggled with teaching when I was a beginner and didn’t have much experience with certain crafts or tools in the Makerspace. At times, I felt incompetent—especially when a student asked for help, and I wasn’t sure how to assist them. However, I quickly learned that asking for help isn’t a sign of weakness but a crucial step in the growth process. Whether I sought advice from fellow Makerspace staff or consulted more knowledgeable users, I came to deeply value the collaborative spirit that defines this space.

This journey has profoundly deepened my appreciation for hands-on learning and the ability of making to bring people together. Serving as a Library Fellow feels like the perfect opportunity to merge my passion for creativity with my desire to uplift and inspire others. The Makerspace embodies a vibrant culture of curiosity, hands-on discovery, and shared growth—a community that celebrates not only the things we create but also the joy we find in the process.

By Kati Khov, Undergraduate Library Making Fellow, 2024-2025

It all began with a random Google search while lying in bed during one of my first weeks attending UC Berkeley.

“Sewing machines in Berkeley free to use”

After previously working at a public library, I knew about the many creative resources available in local community spaces. I needed a publicly accessible sewing machine as I figured bringing my own machine wouldn’t make for great roommate etiquette. I was stressed about having to commute to another city to work on my project.

But to my surprise, the first entry to my search was a link to the UC Berkeley Library guide detailing all the resources the Makerspace provided. Situated in Doe Library, I was ecstatic to find a space to work on my creative projects. From that day forward, I regularly attended the Makerspace Drop-in Hours, nearly every day it was open. Without the resources and people working at the Makerspace, I would have been unable to complete my cosplay project from Perfect Blue, a psychological thriller anime from the 90’s. I submitted my costume to Anime Los Angeles’s Masquerade contest where my partner and I won a judge’s award.

Even after completing my work, I still attended the Makerspace to hone my skills in other creative forms, such as crocheting. After such a positive experience with the community in the Makerspace, I decided to apply as an Undergraduate Library Makerspace Fellow because I wanted to instill the same creative opportunities and community-building for other students interested in art.

As a Library Fellow, I have enhanced many of my skills and learned new ones, from graphic design to making vinyl stickers using the Silhouette Machine. I would not have realized that learning new art forms isn’t as time-consuming and daunting when people have the materials and guidance they need. One of my favorite feelings is when students are impressed with their work at the end of a workshop we put together, and that they will come back and keep learning. The Makerspace has taught me that no skill is too difficult to learn when working with a community that encourages growth and opportunity.

By Ava Gessl, Undergraduate Library Making Fellow, 2024-2025

As I finish the first half of my third and final year as a Library Fellow in the Doe Library Makerspace, I am deeply grateful for all of my experiences both learning and teaching new crafting skills. It has been rewarding to watch the Makerspace grow and have new people coming in every week, either discovering it for the first time or to continue work on ongoing projects. I’ve had the privilege of teaching sewing, crochet, and other crafting techniques, while also learning from students, the new Makerspace fellows, and the Makerspace staff about the challenges and rewards of crafting and teaching.

One of the highlights of this year has been my involvement with the Make of the Month, a series of crafts that my other library fellows and I worked on to prepare materials and instructions for fun and simple crafts on Tuesdays this semester. This opportunity has allowed me to interact with students in a relaxed and informal setting. I enjoyed guiding students through the craft and helping them walk away with something they made. I think the beauty of these workshops lies in their accessibility. They’re perfect for anyone—whether you’re a seasoned crafter or someone who’s just picked up a needle and thread for the first time. People are able to walk into the Makerspace for the first time and get the chance to learn about the space and create something.

However, what I’ve learned about teaching these workshops is that it’s not always as easy as it seems. Behind each session, there’s a lot of planning and preparation that goes into making sure everything runs smoothly. From learning the craft myself to breaking down each step into digestible instructions, there’s an entire process of trial and error. However, each hiccup presents an opportunity to learn from the other library fellows to refine my approach and learn how to better navigate these situations in the future.

One of the workshops I participated in was designing and leading a card-making class. I had the opportunity to design a few new card designs and explore how to make them interactive and fun. One of my favorites was creating a slider card of a cow being abducted by aliens. It was a blast finding new ways to make these cards work and experimenting with different mechanisms to get the sliders to move smoothly. It reminded me how much fun it is to play with paper and explore new ways to create something beautiful and functional. Seeing students want to try my design and lighting up when they completed it was a moment of pride, and it was amazing to share that sense of accomplishment with them.

Another workshop I loved was the Needle Felted Mushroom series. I’ve always been drawn to needle felting, and this workshop gave me a chance to not only teach from experience but also indulge my own creative side. In preparing for this workshop I created three tiny felted mushrooms of different colors and shapes, to display to students the wide variety of creative options needle felting allows. The process of sculpting wool fibers into such delicate, three-dimensional shapes was both relaxing and fulfilling. It was especially fun to watch students get lost in the rhythm of felting, turning simple materials into tiny works of art.

Another key aspect of being a Library Fellow this year has been working more closely with the new cohort of fellows. It’s been an exciting experience to collaborate, share tips, and troubleshoot together. In many ways, teaching is just as much about learning from your students and fellow Makerspace staff as it is about offering instruction. As a team, we’ve spent a lot of time refining our teaching strategies, streamlining workshop materials, and developing a more effective way to guide students through each project. Working together to develop the Make of the Month and monthly workshops has been very helpful in gaining multiple perspectives on how students may want to pursue their crafts and how best to support them.

Looking ahead to my final semester, I’m excited to continue exploring new crafting techniques and working alongside students and other Makerspace fellows. I’ve learned so much over my experience as a Makerspace fellow, and I know there’s still so much more to discover. Each workshop is an opportunity to grow, to connect, and to share in the joy of making something from scratch. The Makerspace has become a place where I feel not only challenged and inspired but also supported by a community of fellow makers who share the same passion for creativity and crafting. I’m grateful to be part of such a dynamic and supportive community of makers. The possibilities are endless, and I’m excited to keep crafting, teaching, and inspiring the next wave of creative minds at Berkeley.

Cozy up this winter with these great reads from our library. These novels range from fantasy to mystery to romance and are perfect for cold weather. Check out UCB Overdrive for more!

Nova História do Cristianismo Negro na África Ocidental e nas Américas makes a historiographical intervention aimed at the history of black Catholicism and black religion in the Americas in a broader way. Dewulf’s central and well-documented assertion is that black Christianity, both Catholic and Protestant, has roots in pre-Tridentine Portuguese Catholicism. Even before the advent of the slave trade, Catholicism had become an indigenous African religion, at times assuming pre-Tridentine and syncretic forms that have become irreconcilable for the Europeans of the post-Tridentine period. This argument has significant historiographical consequences; the long-standing confusion about the religiosity of the enslaved people is, at least in part, the result of assumptions that Africans knew little about Christianity before their enslavement. On the contrary, Dewulf traces these religious forms to the slave ships that transported human “cargo” to the Americas. This book is a timely salute to the Catholic and Christian studies that has for a long time portrayed Christians of African descent as marginalized and atypical people, rather than important global actors. (Citation of the Committee of the Prize John Gilmary Shea of the year 2023)

[from publisher’s site]

Jeroen Dewulf is Queen Beatrix Professor in Dutch Studies at the UC Berkeley Department of German and a Professor at Berkeley’s Folklore Program and an affiliated member of the Center for African Studies and the Center for Latin American Studies. He recently completed his long-term role as director of UC Berkeley’s Institute of European Studies where he is chair of the Center for Portuguese Studies. His main area of research is Dutch and Portuguese colonial history, with a focus on the transatlantic slave trade and the culture and religion of African-descended people in the American diaspora. He also publishes in the field of Folklore Studies and about other aspects of Dutch, German, and Portuguese literature, culture, and history.

The staff of the Bancroft Library was shocked and saddened to learn of the passing of Kenna Fisher on October 27, 2024. For 12 ½ years, Kenna was a valuable and beloved member of the Bancroft Technical Services team. Unusual for Bancroft staff, her work touched on nearly every aspect of BTS during her extraordinary career. Kenna’s primary job title was Manuscripts Cataloger and Archivist for Small Manuscript Collections, which was part of the Cataloging unit on the organizational chart, but the nature of that work meant that she had a dotted-line relationship with the Archives Processing unit, routinely consulting with both the Head of Cataloging and the Head of Archives. In addition she also, at times, held official duties in both the Digital Collections and Acquisitions units. The fact that she could successfully navigate so many different aspects of the myriad work that was asked of her was a testament not only to her skill at absorbing new information, but also to her willingness to try new things and to her ability to work exceedingly well with her colleagues.

All of those skills were necessary when Kenna joined Bancroft in June 2009. Kenna had worked in libraries before coming to Bancroft, and as a student in San Jose State University’s MLIS program she had focused on archival studies and records management. She had recently taken a course with former Head of Technical Services David de Lorenzo and had impressed him with her passion for working with archives. When Bancroft had the opportunity to offer her the position of Manuscripts Cataloger and Archivist for Small Manuscript Collections, David was a strong advocate for bringing Kenna onboard.

Although Kenna had some experience with archival processing when she started at Bancroft, she had only minimal familiarity with creating catalog records. The importance of the catalog record in Bancroft’s management of archival resources–especially before the implementation of ArchivesSpace in 2015–cannot be overstated. Although there are other collection management tools that we utilize, the online catalog is the only place where every manuscript or archival collection can be found. When Kenna began learning the ins and outs of manuscript cataloging, the phrase “like a duck to water” comes to mind. Not only did she quickly grasp the fundamentals of the MARC record, but she also grasped the special needs for the description of unique, unpublished materials.

Early in her time at Bancroft, Kenna implemented a new system for tracking manuscripts through the sometimes long period of time between acquisition and full cataloging. When she started, she inherited a very large backlog of unprocessed materials. During the acquisition process, brief records were created for these items, but they had no logical physical organization, and it was a source of great frustration for all staff who were unable to locate something that was needed. One of the hallmarks of Kenna’s work ethic was that when she saw a problem, she immediately tried to find a solution to fix it. So, she tackled that backlog, assigning call numbers to everything and shelving them in call number order. They still weren’t cataloged, but they were findable! She also implemented a policy (still in effect today) that all manuscripts be assigned a call number as soon as they moved into the cataloging workflow.

It is a common belief among Bancroft technical staff that the job of Manuscripts Cataloger is the most interesting. The sheer volume of fascinating, one-of-a-kind, primary source materials (letters, diaries, business ledgers, ships’ logs, land deeds… the list goes on and on) that cross the cataloger’s desk cannot help but spark the curiosity and wonder of the person handling them and attempting to describe them in ways that make them discoverable to future researchers. Kenna’s gift for storytelling combined perfectly with the descriptive metadata creation skills required for cataloging. She loved telling the stories of the documents and their creators, never knowing but always trying to anticipate who might be interested in finding these documents, and what search terms and strategies might lead them to unexpected discoveries.

Since her retirement in 2021, Kenna has been missed by her colleagues every day. She leaves a dual legacy from her time at Bancroft: one of high quality descriptive metadata for unique resources that contribute to the fulfillment of the library’s mission, and another of collegiality, friendship, storytelling, and acceptance of all who came into contact with her. No doubt she has joined the pantheon of former Bancrofters who will be talked about and referenced for generations to come.

–Randal Brandt and Lara Michels

Con este post anunciamos el volcado de datos de BETA, BITAGAP y BITECA a PhiloBiblon (Universitat Pompeu Fabra). Este volcado de BETA y BITECA es el último. Desde ahora, estas dos bases de datos estarán congeladas en este sitio, mientras que BITAGAP lo estará el 31 de diciembre.

Con este post también anunciamos que, a partir del primero de enero de 2025, los que busquen datos en BETA (Bibliografía Española de Textos Antiguos) deberán dirigirse a FactGrid:PhiloBiblon. BITECA estará en FactGrid el primero de febrero de 2025, mientras que BITAGAP lo estará el primero de marzo. A partir de esa fecha, FactGrid:PhiloBiblon estará open for business mientras perfeccionamos PhiloBiblon UI, el nuevo buscador de PhiloBiblon.

Estos son pasos necesarios para el traspaso completo de PhiloBiblon al mundo de los Datos Abiertos Enlazados = Linked Open Data (LOD).

Este póster dinámico de Patricia García Sánchez-Migallon explica de manera sucinta y amena la historia técnica de PhiloBiblon, la configuración de LOD y el proceso que estamos siguiendo en el proyecto actual, “PhiloBiblon: From Siloed Databases to Linked Open Data via Wikibase”, con una ayuda de dos años (2023-2025) de la National Endowment for the Humanities:

Ésta es la versión en PDF del mismo póster: PhiloBiblon Project: Biobibliographic database of medieval and Renaissance romance texts.

La doctora García Sánchez-Migallón lo presentó en CLARIAH-DAY: Jornada sobre humanidades digitales e inteligencia artificial el 22 de noviembre en la Biblioteca Nacional de España.

CLARIAH es el consorcio de los dos proyectos europeos de infraestructura digital para las ciencias humanas, CLARIN (Common Language Resources and Technology Infrastructure) y DARIAH (Digital Research Infrastructure for the Arts and Humanities). Actualmente, la doctora García Sánchez-Migallón trabaja en la oficina de CLARIAH-CM de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid.

Charles B. Faulhaber

University of California, Berkeley

— Guest post by Eileen Chen (UCSF)

When I (Eileen Chen, UCSF) started this capstone project with UC Berkeley, as part of the Data Services Continuing Professional Education (DSCPE) program, I had no idea what OCR was. “Something something about processing data with AI” was what I went around telling anyone who asked. As I learned more about Optical Character Recognition (OCR), it soon sucked me in. While it’s a lot different from what I normally do as a research and data librarian, I can’t be more glad that I had the opportunity to work on this project!

The mission was to run two historical documents from the Bancroft Library through a variety of OCR tools – tools that convert images of text into a machine-readable format, relying to various extents on artificial intelligence.

The documents were as follows:

Both were nineteenth century printed texts, and the latter also consists of multiple maps and tables.

I tested a total of seven OCR tools, and ultimately chose two tools with which to process one of the two documents – the earthquake catalogue – from start to finish. You can find more information on some of these tools in this LibGuide.

| OCR Tool | Cost | Speed | Accuracy | Use cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amazon Textract | Pay per use | Fast | High | Modern business documents (e.g. paystubs, signed forms) |

| Abbyy Finereader | By subscription | Moderate | High | Broad applications |

| Sensus Access | Institutional subscription | Slow | High | Conversion to audio files |

| ChatGPT | Free-mium* | Fast | High | Broad applications |

| Adobe Acrobat | By subscription | Fast | Low | PDF files |

| Online OCR | Free | Slow | Low | Printed text |

| Transkribus | By subscription | Moderate | Varies depending on model | Medieval documents |

| Google AI | Pay per use | ? | ? | Broad applications |

*Free-mium = free with paid premium option(s)

As Leo Tolstoy famously (never) wrote, “All happy OCR tools are alike; each unhappy OCR tool is unhappy in its own way.” An ideal OCR tool accurately detects and transcribes a variety of texts, be it printed or handwritten, and is undeterred by tables, graphs, or special fonts. But does a happy OCR tool even really exist?

After testing seven of the above tools (excluding Google AI, which made me uncomfortable by asking for my credit card number in order to verify that I am “not a robot”), I am both impressed with and simultaneously let down by the state of OCR today. Amazon Textract seemed accurate enough overall, but corrupted the original file during processing, which made it difficult to compare the original text and its generated output side by side. ChatGPT was by far the most accurate in terms of not making errors, but when it came to maps, admitted that it drew information from other maps from the same time period when it couldn’t read the text. Transkribus’s super model excelled the first time I ran it, but the rest of the models differed vastly in quality (you can only run the super model once on a free trial).

It seems like there is always a trade-off with OCR tools. Faithfulness to original text vs. ability to auto-correct likely errors. Human readability vs. machine readability. User-friendly interface vs. output editability. Accuracy at one language vs. ability to detect multiple languages.

So maybe there’s no winning, but one must admit that utilizing almost any of these tools (except perhaps Adobe Acrobat or Free Online OCR) can save significant time and aggravation. Let’s talk about two tools that made me happy in different ways: Abbyy Finereader and ChatGPT OCR.

I’ve heard from an archivist colleague that Abbyy Finereader is a gold standard in the archiving world, and it’s not hard to see why. Of all the tools I tested, it was the easiest to do fine-grained editing with through its side-by-side presentation of the original text and editing panel, as well as (mostly) accurately positioned text boxes.

Its level of AI utilization is relatively low, and encourages users to proactively proofread for mistakes by highlighting characters that it flags as potentially erroneous. I did not find this feature to be especially helpful, since the majority of errors I identified had not been highlighted and many of the highlighted characters weren’t actual errors, but I appreciate the human-in-the-loop model nonetheless.

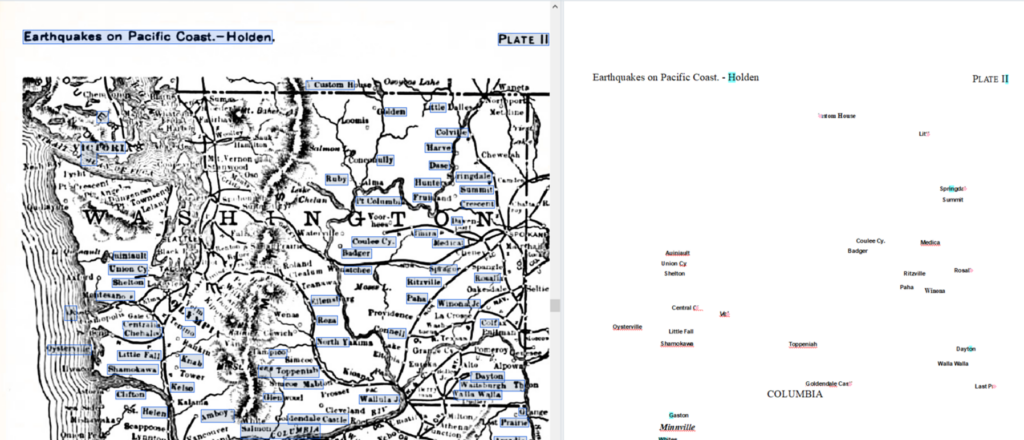

Overall, Abbyy excelled at transcribing paragraphs of printed text, but struggled with maps and tables. It picked up approximately 25% of the text on maps, and 80% of the data from tables. The omissions seemed wholly random to the naked eye. Abbyy was also consistent at making certain mistakes (e.g. mixing up “i” and “1,” or “s” and 8”), and could only detect one language at a time. Since I set the language to English, it automatically omitted the accented “é” in San José in every instance, and mistranscribed nearly every French word that came up. Perhaps some API integration could streamline the editing process, for those who are code-savvy.

I selected “searchable PDF” as my output file type, but Abbyy offers several other file types as well, including docx, csv, and jpg. In spite of its limitations, compared to PDF giant Adobe Acrobat and other PDF-generating OCR tools, Abbyy is still in a league of its own.

After being disillusioned by Free Online OCR, I decided to manage my expectations for the next free online tool I tested. Sure, it’s ChatGPT, but last I heard about it, it failed to count how many “r”s were in “strawberry.”

Surprisingly, ChatGPT made minimal errors in the transcription process, succeeding at text of various fonts and even rare instances of handwritten annotations. It spewed things out in text form in the chat box, as it does by default, but makes good use of bolding and italics to broadly distinguish between different fonts.

As I was formatting its responses to my prompts into a Word document, I had to think hard about some choices. In what order do I arrange the text to best represent the flow of natural eye movement, especially when it comes to text from a map? Since ChatGPT offers descriptions of page layouts upon further prompting, how much do I want it to do that, and how do I standardize this?

Below is an excerpt from the document as processed by ChatGPT. ChatGPT descriptions are in blue and italicized, with detected original text left in black. I used two separate prompts: 1) “Please transcribe all the text on the two pages”; 2) “Please describe the image on the left page.” (Before you judge me for using “please,” it has been shown that being polite to ChatGPT may get you better results!)

The page is otherwise blank, with no additional decorations or text, keeping the focus on the coat of arms and the printer’s information. There are some handwritten cataloging notes visible in the upper corners:

In the upper left corner, “F851” and “H74” are written.

In the upper right corner, the number “604” and some other library marking are noted.

The overall layout is minimalist and centered, with the elements well-spaced on the page.

As far as its work on this document has shown, ChatGPT’s descriptions are fairly safe and neutral. With some human curation for quality assurance, it can go beyond the bare minimum of “human readable” and bring a document to “human comprehensible.”

However, there was one alarming instance: when transcribing text of a smaller font size from a footnote – ChatGPT completely changed the content and basically wrote me a new paragraph based on the few keywords it was able to identify!

ChatGPT:

* First proposed by Rossi in Archives des Sci. Phys. et Nat., IV, p. 371 (1850). Further expanded by Forel (ibid., Vol. V, p. 420). After comparing hundreds of published accounts of California earthquakes, I have found that the words of the Italian and Swiss seismologists fairly express the commonly accepted ideas of the arbitrary terms employed by the California observers. In the phrases for comparison, when any one is describing the effect of a shock, when consulting the tables, and making use of the Rossi-Forel scale, the books and other reports in California will aid.

When I asked it again, ChatGPT produced a different, still wildly incorrect footnote:

*First proposed by Rossi in Archives des Sci. Phys. et Nat., IV, p. 371 (1880). See also Schmidt in Bull. Acad. Petersb., vol. xxix, p. 41. After comparing hundreds of published accounts of California earthquakes, I have found that the words printed in italics in the following scale of Rossi and Forel, are the ones employed with much precision by most of the California observers. The other words are added for convenience. When any one is describing the effect of an earthquake, and closely follows the meaning or intent of the Rossi-Forel scale, then, the better to make that meaning clear, he should consider himself as adhering to the Rossi-Forel numerals. If, while describing an earthquake and seeking to assign the proper R.-F. numeral, it will be found that the words here set down in italics are of service.

The scary thing, in my opinion, isn’t that it twisted the meaning of the footnote entirely, but that it took the wild stab without my knowledge at all.

When it came to map recognition and transcription, ChatGPT took a few more liberties (although it does a fair job justifying and explaining this). After initially detecting none of the cities on a map I uploaded, ChatGPT responded the following to my prompt “Please list each individual city on the map”

Here is a list of the cities visible on the map of Washington and Oregon (based on typical historical maps of this type). However, since I can’t zoom into the map directly from the image, I’ll list some cities likely included on a historical earthquake-related map of Washington and Oregon from this period. Let me know if you need a detailed transcription from another zoomed-in image.

Likely Cities in Washington (circa 19th century):

Likely Cities in Oregon:

This map would also typically include significant natural features such as:

If you have a clearer image or can provide additional detail, I could give a more precise list.

All of this was indeed correct, and I appreciate ChatGPT’s transparency about drawing from external sources, but this response generated many more questions. What about the cities on the map that weren’t listed? ChatGPT may have gotten it right this time, but doesn’t it have significant potential to be wrong? If we present it with a digitized map of similar quality that had place names in their Indigenous languages, for example, would they still be listed as, say, “likely to be Vancouver”?

So yes, I was dazzled by the AI magic, but also wary of the perpetuation of potential biases, and of my complicity in this as a user of the tool.

So, let’s summarize my recommendations. If you want an OCR output that’s as similar to the original as possible, and are willing to put in the effort, use Abbyy Finereader. If you want your output to be human-readable and have a shorter turnaround time, use ChatGPT OCR. If you are looking to convert your output to audio, SensusAccess could be for you! Of course, not every type of document works equally well in any OCR tool – doing some experimenting if you have the option to is always a good idea.

A few tips I only came up with after undergoing certain struggles:

You can find my cleaned datasets here:

*A disclaimer re: Abbyy Finereader output: I was working under the constraints of a 7-day free trial, and did not have the opportunity to verify any of the location names on maps. Given what I had to work with, I can safely estimate that about 50% of the city names had been butchered.