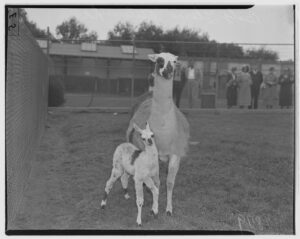

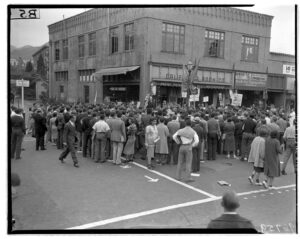

As part of the UC Berkeley University Library’s ongoing commitment to make all our collections easier to use, reuse, and publish from, we are excited to announce that we have just eliminated licensing hurdles for use of over 5 million photographs taken by San Francisco Examiner staff photographers in our Fang family San Francisco examiner photograph archive negative files, BANC PIC 2006.029–NEG, and Fang family San Francisco examiner photograph archive photographic print files, BANC PIC 2006.029–PIC.

Every photograph within these photographic print and negative collections that were taken by an SF Examiner staff photographer are now licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license (CC BY 4.0). This means that anyone around the world can incorporate these photos into papers, projects, and productions—even commercial ones—without ever getting further permission or another license from us.

What is the San Francisco Examiner collection?

The SF Examiner has been published since 1863, and continues to be one of The City’s daily newspapers. It was acquired by George Hearst in 1880 and given to his son, William Randolph Hearst, in 1887. It was the founding cornerstone of the Hearst media empire, and remained part of the Hearst Corporation’s holdings until it was sold, in 2000, to the Fang family of San Francisco. In 2006 the Examiner’s photo morgue, totaling over 5 million individual images, was donated to The Bancroft Library by the Fang family’s successors, the SF Newspaper Company, LLC.

Along with the gift of negatives and photographic prints, the copyright to all photographs taken by SF Examiner staff photographers was transferred to the UC Regents, to be managed by UC Berkeley Library. However, the copyright to works (mainly in the form of photographic prints) that appear in the collection that were not created by SF Examiner staff was not part of the copyright transfer to the University. Copyright to any works not taken by SF Examiner staff is presumed to rest with the originating agency or photographer. The Library maintains a list of known SF Examiner staff photographers and can assist in making identification of particular photographs until the metadata has been updated.

What has changed about the collection?

Although people did not previously need the UC Regents’ permission (sometimes called a “license”) to make fair uses of our SF Examiner photograph archive, because of the progressive permissions policy we created, prior to January 2024 people did need a license to reuse these works if their intended use exceeded fair use. As a result, hundreds of book publishers, journals, and film-makers sought licenses from the Library each year to publish our Examiner photos.

The UC Berkeley Library recognized this as an unnecessary barrier for research and scholarship, and has now exercised its authority on behalf of the UC Regents to freely license the SF Examiner photographs in our collection that were taken by staff photographers under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license (CC BY 4.0). This license is designed for maximum dissemination and use of the materials.

How to use SF Examiner collection photographs

Now that the photographs by SF Examiner staff photographers have a CC BY license applied to them, no additional permission or license from the UC Regents or anyone else is needed to use these works, even if you are using the work for commercial purposes. No fees will be charged, and no additional paperwork is necessary from us for you to proceed with your use.

Making your usage even easier is the fact that over 22,000 of these negative strips have been digitized and made available via the Library’s Digital Collections Site, and the finding aid for the prints and negatives have more information about the photographs that have not yet been digitized.

The CC BY license does require attribution to the copyright owner, which in this case is the UC Regents. Researchers are asked to attribute use of reproductions subject to this policy as follows, or in accordance with discipline-specific standards:

Fang family San Francisco Examiner photograph archive, © The Regents of the University of California, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley. This work is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license.

One final note on usage: While the SF Examiner Collection now carries a CC BY license, this does not mean that other federal or state laws or contractual agreements do not apply to their use and distribution. For instance, there may be sensitive material protected by privacy laws, or intended uses that might fall under state rights of publicity. It is the researcher’s responsibility to assess permissible uses under all other laws and conditions. Please see our Permissions Policy for more information.

Other Library collections with a CC BY license

The Fang family San Francisco Examiner photograph archive joins a number of other collections that the Library has opened under a CC BY license, including the photo morgue of the San Francisco News-Call Bulletin. All of the collections that have had a CC BY license applied can be found on our Easy to Use Collections page.

Happy researching!