Author: UC Berkeley Library

Learn about Juneteenth through Oral History

Scholars from many fields will be interested in interviewees who recall their experiences of Juneteenth

“Juneteenth was usually two days of real fun. . . . For those big picnics, people would come from Dallas, Fort Worth, well, just from miles around. I would think hundred miles or two hundred miles. . . . That was a time of reunion when all the families would come back.”

So remembers Selena Foster, the daughter of sharecroppers from Cherokee County, Texas, who was interviewed for the Oral History Center’s On the Waterfront: Richmond, California Oral History Project. Foster went on to recall the barbecues, the ice cream, the best food she ever ate, the festivities, and the large family reunions.

This is the first year that Juneteenth is being observed as an official national holiday. Juneteenth commemorates that day on June 19, 1865, when union soldiers arrived in Galveston, Texas, and formally announced that slavery was over and enslaved people were free. The Oral History Center has three interviews with narrators who talk about Juneteenth. While the references to Juneteenth in these interviews are brief, they reveal something about each narrator – the pride of starting the first Juneteenth parade in Richmond, California; the happy memories of family reunions in Cherokee County, Texas; and the involved approach of a teacher with her preschool students’ families.

Beyond that, scholars from many disciplines will find much of interest in the oral histories of these three women from three different backgrounds, all of whom landed in the Bay Area. Scholars studying everything from African American history to urban development, women’s history, community history, demographics, early education, higher education, theater, migration, the World War II home front — the list goes on — will find something in these oral histories to enhance their research.

Find these and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.

Margaret Wilkerson: A Life in Theater and Higher Education

Margaret Wilkerson was interviewed as part of the UC Berkeley African American Faculty and Senior Staff Oral History Project. A scholar of theater with a focus on Black women playwrights including Lorraine Hansbury, Wilkerson served as chair of the UC Berkeley departments of Theater, Dance, and Performance Studies and African American Studies, and also served as director of Berkeley’s Center for the Study, Education, and Advancement of Women. In her oral history, Wilkerson discusses her childhood in an integrated community in Los Angeles, her life experiences, scholarship, and administrative work in higher education on behalf of equity and access.

Wilkerson, together with fellow UC Berkeley alum Lamarr Ferguson, organized the first Juneteenth parade in Richmond, California. It started as a small event through a local church, and was expanded to an annual citywide event through the City of Richmond that still takes place. Wilkerson recalls the first fair:

[We] picked up the kids and brought them down, and taught them about Juneteenth, and did makeup on their faces and things like that, and then took them back home. We had sent fliers out, delivered fliers in the neighborhood to let people know what was going to happen on that day and that we’d like to take the kids. We came down and they let us do it because we all lived in the neighborhood and they all knew us. I felt very proud that we did that for a couple of years and then after we stopped doing it, the City of Richmond picked that up and began to have a city-wide Juneteenth celebration.

Selena Foster: A Longtime Richmond Resident from Cherokee County, Texas

Selena Foster was interviewed as part of the On the Waterfront: Richmond, California Oral History Project. Born in 1916 in Texas to sharecroppers, Foster migrated to California in 1944, where her husband found work with the Kaiser Shipyards. Foster started out making donuts at a diner and soon after launched her own restaurant. In her oral history, Foster discusses her childhood in Texas, religion and church life, discrimination, housing, early Black families in Richmond, and Richmond’s development.

Foster details her childhood experiences in Cherokee County, Texas, and in that context recalled how important Juneteenth was in Texas and to her family. She remembers her family’s celebrations of the holiday:

Now, the Juneteenth, which is going to be celebrated here in Richmond this week, we had every year back there. That was one of the big celebrations in the middle of the year. Juneteenth was usually two days of real fun. The one day was getting everything ready and putting up the carnivals and then the big day of the celebration. My grandfathers all barbequed, and several other men that I know of there. They made their pits in the ground, unlike today. They would kill the cattle themselves. They would kill the beef off and wash it down and hang it and whatever they’d do to it, they say to tenderize it.

Then they would cook all night for two or three nights. That would be some of the best meat I ever ate in my life. And they had no ice and refrigeration. They would put the meat down in the well to cool it, to keep it from spoiling. That’s the way my grandmother used to do her butter.

So, for those big picnics, people would come from Dallas, Fort Worth, well, just from miles around. I would think hundred miles or two hundred miles. You would get to have that big reunion. That was a time of reunion when all the families would come back. My birthday, incidentally, is the twentieth of June. I always had a birthday party. I got ice cream for my birthday.

Sharon Fogelson: Rosie The Riveter World War II American Home Front Oral History Project

Sharon Fogelson was interviewed as part of the Rosie the Riveter World War II Home Front Oral History Project, in partnership with the National Park Service. Born in 1943, Fogelson was a preschool teacher and later head teacher with the Pullman School in Richmond, California. In her interview Fogelson discusses the changing demographics of Oakland and Richmond, where she lived and worked, in the several decades after WWII, as well as segregation and poverty in Richmond, shifts in federal funding for schools, early education, teaching methodology, standardized testing, and gender discrimination.

Fogelson talks about Juneteenth in the context of building rapport with the parents of her students. She explains that she would relate to parents through discussions of holidays, such as Thanksgiving and Juneteenth. Fogelson specifically references Richmond’s annual Juneteenth fair, the one that Wilkerson had founded.

If there was an event in the community, like they would have a Juneteenth fair at Nicholl Park, I would ask them, did they go to that? And if they haven’t been, next year they should try to make it a priority, because it’s a really exciting affair to go to, for your children, because there’s things there about your own culture. So we just talked about everything. If you make what some people call small talk with people, and they sort of get to know you, they start to build a trusting relationship with you. So then if something isn’t going right in their family, they feel more comfortable saying, “Do you have a couple minutes I could talk to you?” Because you don’t threaten them. They feel sort of like you’re almost a friend. So I’ve always found that you make conversation with whatever the parent is interested in talking about, and how important—

I don’t think sometimes people in education realize that a casual relationship and that daily interaction that you have — it’s something in elementary through high school — teachers don’t have the opportunity to do that.

These oral histories provide a glimpse into how the holiday of Juneteenth was valued and celebrated. Even more, the three narrators who recalled Juneteenth have much to share about the pressing social issues of their day — and ours.

You can find these and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Just type a name or key word and click “search.” To ensure a full text search, on the next page scroll down and toggle on the button that says “full text.” If you’re interested in African American history in particular, see our related collection guide, A Host of Hidden Gems: Interviews with African Americans throughout the Oral History Center Collection. You can also visit all our collection guides and our projects page to find oral histories on specific subjects.

They’ve made a difference at UC Berkeley. Who are you thinking of right now?

Nominate someone who’s made an impact at UC Berkeley and we’ll interview them for an oral history

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library has been around since 1953 and we’ve been documenting the history of UC Berkeley ever since. Is there a Berkeley faculty, administrator, or staff person — past or present — who’s made an impact on campus? This is your opportunity to nominate someone who has made an outstanding contribution to campus life — or to the teaching, research, or public service mission of the university — and we’ll interview the selected candidate for posterity.

They’ve made a difference at UC Berkeley. Who are you thinking of right now?

Nominations for the “Class of ’31 Oral History” are due by June 30, 2021. (Nomination form.) If you have any questions, please contact Oral History Center Director Martin Meeker at mmeeker@library.berkeley.edu. Selection criteria for nominees include willingness of the nominee to participate, uniqueness of the nominee’s story, and level of contribution to campus life, among others. This oral history honor has been made possible by a generous endowment from the class of ’31.

A spirit of gratitude

Upon the fiftieth anniversary of their graduation, hundreds of members of the Berkeley class of 1931 “joined together,” as class president Lois L. Swabel put it, “in a spirit of gratitude and admiration for their alma mater” — endowing an oral history series through The Bancroft Library. Their goal was to recognize the university for the “strength and skills” gained through a Berkeley education, and honor those who have made outstanding contributions to the community. Past interviews have celebrated campus leaders as diverse as Fred S. Stripp Jr, rhetoric instructor who has been described as the “heart and soul” of the Berkeley Debate Team, Anne DeGruchy Dettner, pioneering researcher at the Berkeley Radiation Lab (now Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory), and our most recent honoree, Susan Graham, professor of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, whose oral history is currently in progress.

Documenting UC Berkeley’s contributions through oral history

Over the years, the Oral History Center has interviewed hundreds of UC Berkeley faculty, staff, and alumni. You can learn about their experiences through The Berkeley Remix podcast series, including the episode Once in a Career Fire, about the 1991 Oakland Hills Fire, and the Let There Be Light season, including Berkeley Lightning, about game changing technology developed by Berkeley Engineering faculty and students.

Honorees interviewed for the Class of ’31 Community Leaders series can be found within the Education and University of California – Individual Interviews and throughout our collection. Oral history projects about UC Berkeley consisting of multiple interviews include: Athletics at UC Berkeley, The Free Speech Movement, UC Berkeley History Department, The Originals (African American Faculty and Senior Staff), and SLATE (student political organization, 1958–66). Even more interviews of Berkeley alumni, staff, and faculty can be found in various projects throughout our archive. Reaching back to the class of 1895, these include narrators who were influential as educators, labor organizers, suffragists, scientists, community organizers, philanthropists, novelists, artists, and much more. More than 200 of these can be found in our Berkeley Women 150 oral history collection guide.

Find these and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.

Call for comment: South/Southeast Asia Library

Note: The UC Berkeley Library has announced its decision to withdraw the proposal for the South/Southeast Asia Library. Read more.

This week, a call for comment issued by UC Berkeley’s University Librarian Jeffrey MacKie-Mason, College of Letters & Science’s Division of Arts & Humanities Dean Anthony Cascardi, and Division of Social Sciences Dean Raka Ray encourages anyone interested to carefully read the Library’s proposed plan for the South/Southeast Asia Library at UC Berkeley and to share comments and recommendations.

The comment period is open through Friday, April 9. We invite you to submit comments via email to libraryforum@lists.berkeley.edu.

The Library has developed a proposed vision for the South/Southeast Asia Library collections and services to be integrated with the Doe Library and Main (Gardner) Stacks in 2021.

The Commission on the Future of the UC Berkeley Library report (2013) asserted that the consolidation of campus libraries “could reduce costs, increase efficiency, and improve the quality of collection development and service delivery to both students and faculty,” and encouraged the university librarian to work with academic leaders to “identify where and how space usage can be improved for user communities and service delivery better attuned to the needs of users.” In recent years the Library has closed, merged, and re-envisioned several campus libraries in response to changing user needs, emerging programs, and campus space-planning decisions.

Zotero Day – January 26 and February 1

Do you … ?

- … save random URLs in a Word or Google Doc?

- … save article PDFs on your desktop and as email attachments?

- … have a pile of article printouts sitting on your desk?

- … write down citations on sticky notes and post them to your monitor?

- … stay up late the night before a paper is due reconstructing your citations?

If you answered yes to any of the above … the answer is YES, you need Zotero (or some other citation management system).* Come to Zotero Day and learn more about this powerful tool for organizing your citations and creating bibliographies. Jennifer Dorner and David Eifler have been tag-team teaching Zotero classes which were very successful last semester, with one attracting over 150 attendees!

Spend an hour with Jennifer and David and learn to use this robust citation manager with Firefox and Chrome. These zoom workshop covers importing citations, exporting bibliographies into Word and Google Docs and sharing resources among groups. Three 1-hour sessions each day. (If you have a chance, download the program and browser connector at www.zotero.org before the workshop.)

Tuesday, January 26 (all classes are Pacific Standard Time)

- 10AM – 11AM

- Noon – 1PM

- 5PM – 6PM

Monday, February 1

- 9AM – 10AM

- 2PM – 3PM

- 4PM – 5PM

Please register to get the Zoom link – https://berkeley.libcal.com/calendar/workshops

* * * * * * * * * * * *

Can’t make it to these workshops? Try a self-paced tutorial? This tutorial includes 24 slides and 18 embedded screencasts (totalling approximately 18 minutes of viewing). Do the tutorial at your own pace and skip or fast-forward through the screencasts. In total, the tutorial can take anywhere from 15 minutes to an hour. Check it out at: Zotero Basics

* * * * * * * * * * * *

* adapted from Why use a citation management tool?, Gallagher Law Library, University of Washington.

COVID Chronicles: ICYMI edition

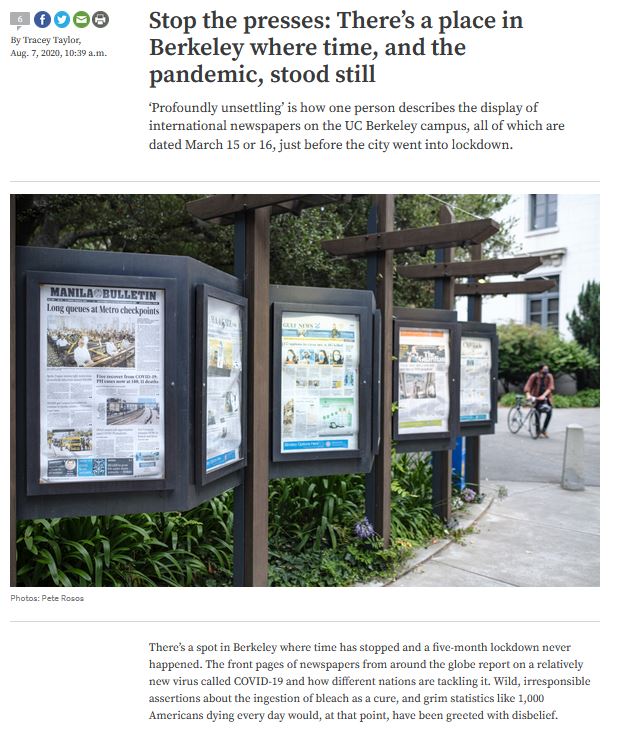

International Newspaper Display at Moffitt Library

It started with a tweet, back in July, by Berkeley City Councilmember Rigel Robinson (UCB 2018) describing the international newspaper display outside of Moffitt Library.

Robinson’s tweet got picked up by Berkeleyside, the online news source for all things Berkeley. The Berkeleyside story provided background on the international newspaper display in the plaza outside Moffitt Library and the Free Speech Movement Cafe and spoke with our Social Sciences Division colleague, Glenn Gillespie, Reference/Government Information Specialist.

Just to play up the whole time warp/time capsule theme, it has been four months since this story appeared. And, at the time, it had been five months since the newspapers had been updated. Where exactly did 2020 go? Has it been the longest year on record? Or the shortest?

Funding and Federal Authority: Obstacles in AIDS Research and Treatment

Guest high school blogger uses UC Berkeley Oral History Center interviews to write about Funding and Federal Authority in AIDS Research and Treatment. This is part three of a 3-part series. Resources for teachers are at the end of the article.

Obstacles in AIDS Research and Treatment: Funding and Federal Authority

By Ella S. Damty

Sophomore, El Cerrito High School

As with any disease or scientific endeavor, research on AIDS required money. The federal government at the time didn’t have an efficient system to approve funds for projects that desperately needed it, like AIDS. This difficulty was compounded by the fact that funds might not be approved at all, because federal officials weren’t always convinced that AIDS was an important disease to research. Medical researchers had to work with little to no funding or equipment to research and treat AIDS until the first federal funds were approved by Congress in 1983.

Don Abrams, an oncologist studying AIDS, describes his experience writing a grant proposal for the National Institutes of Health, and the bureaucratic mistakes that delayed his funding. He recalls that his grant proposal was lost and put into the wrong category, so instead of being weighed against the six other applicants for the program he applied to, it was considered with hundreds of others for a different type of grant.

In addition to navigating slow federal bureaucracy, researchers had to contend with the government’s belief that AIDS wasn’t a lasting or serious disease. Their proposals weren’t always reviewed because for several years they were seen as a waste of time. Art Ammann, a specialist in pediatric AIDS, explains,

Again, who was going to review [an application for AIDS research funds] if most people didn’t believe that this epidemic was a problem to begin with? So grants got rejected and individuals had to reapply—maybe a two-year process. So research on AIDS was done initially by people who had funding which they could use flexibly…. A federal funding mechanism didn’t get built until people accepted AIDS as a disease, and the government put money into that area. (Ammann, 64)

When the federal government finally realized that AIDS was an important disease to research, the grantors (such as the NIH) wanted to maintain control over both the funds and the researchers because of the money and awards that could be earned. But, as Marcus Conant, the dermatologist who first diagnosed Kaposi’s Sarcoma in AIDS patients, describes, “The problem with that is that when the government retains control, it by definition slows down the process. There are very few examples where the government’s been in control of something that has moved rapidly.” (Conant, 152)

Conant goes on to describe a specific instance where quicker funding could have made a difference in thousands of lives: Jay Levy, the doctor who developed the HIV antibody test, had put in a request for funding to get a fume hood, so that he could work with viruses. Had he gotten it, he could have been the first to discover the virus months earlier, and developed the antibody test sooner. The number of AIDS cases caused by blood transfusions could have been greatly reduced if blood could have been tested sooner.

Through their oral histories, medical researchers show how government bureaucracy and reluctance to fund AIDS research greatly slowed the efforts to find a cause and a treatment for the devastating disease. But these oral histories also show that doctors and researchers did the best they could and valiantly soldiered on, saving thousands of lives.

Photo: AIDS protest at Federal Drug Administration offices in Washington, DC, 1988. (UC San Francisco, Library, Special Collections. Source: Calisphere)

Resources for Teachers

Student project: See the website by Ella S. Damty, based on the class assignment developed by UC Berkeley undergraduate research apprentice Corina Chen: Virus Hunters Newsletter: Obstacles in AIDS Research and Treatment

Education resources, including how-to on interviewing, tips for searching our collection, and the complete AIDS/HIV curriculum with sample assignments.

Seven-episode podcast: First Response: AIDS and Community in San Francisco.

All interviews in the AIDS Epidemic in San Francisco Oral History project.

“The True Experience of Terror:” Fear in the Medical Community in AIDS Research and Treatment

Guest high school blogger uses UC Berkeley Oral History Center interviews to write about Fear in the Medical Community in AIDS Research and Treatment. This is part two of a 3-part series. Resources for teachers are at the end of the article, including the Oral History Center’s Epidemics in History—HIV/AIDS Curriculum.

By Ella S. Damty

Sophomore, El Cerrito High School

In the early years of the AIDS epidemic, no one knew what the disease was or how it was transmitted. This led to medical professionals who treated AIDS patients at San Francisco General Hospital to fear for their lives, not knowing whether they could get the disease themselves. This fear was particularly intense for gay health professionals, who were already in a high-risk group. This fear subsided for medical professionals once the HIV antibody test was developed in 1985, but in the years before that, fear plagued doctors and other health workers.

Doctors treating AIDS patients in the beginning didn’t use any protective measures when treating patients, including taking their blood for testing. Andrew Moss led the first epidemiological study of gay men with AIDS. On why health workers didn’t use gloves or other protective measures, he says, “Denial. We were refusing to acknowledge how afraid we were.” Moss went on to explain that despite the denial, the health professionals lived in fear.

We all thought we were going to die. By the middle of the next year, 1984, we all thought we were going to die. Volberding thought he was going to die. He was going around saying, “Oh, my lymphadenopathy is bad today.” He thought he had AIDS. He thought he had given it to his wife and his kids. Everybody did. I went to see my doctor five times. (Moss, 283)

Moss describes the period between 1983–1985, as “the true experience of terror.” During this time, he was working with patients, but the antibody test had not yet been developed. The lack of knowledge on who could get it or who had it was terrifying to health workers. “It was a period of maximum paranoia. Nobody knew who was getting infected (Moss, 283).”

Paul Volberding was an oncologist who first became involved in AIDS while treating patients with Kaposi Sarcoma. He created and worked in the AIDS clinic in San Francisco General. He describes the environment in his home during this period, and how when he developed any sort of sickness or fever, he thought he had AIDS, but wasn’t allowed to discuss it.

There was about a year or year and a half period where the anxiety was so great that AIDS was just not permitted as a discussion item at home. There was so much anxiety attached to it that if I’d say, “Gee, I’m worried about taking care of these patients. I’m worried I have a fever, maybe this is PCP,” my wife, Molly, wouldn’t let me talk about it. (Volberding, 122)

After the HIV antibody test was developed in 1985, all the health workers in the AIDS ward were tested, and most came back negative, except for some of the gay employees. At this point the fear was over for people like Volberding and Moss, married heterosexual men. But the risk remained for gay health workers, and Moss recalls several coworkers who ended up dying from AIDS, and informing them of their test results.

In January 1985, I tested myself, when I had seen how the results were coming in. All the heterosexuals were negative. It was a very difficult study to do. There were a lot of gay men working in the clinic, and one-third of them were positive. And they’re dead now. Philippe Roy, the receptionist, the Shanti social worker, Gary Starliper, and a whole bunch of people that worked there are now dead. We tested them and they were positive, and I had to tell them. (Moss, 283–284)

The fear of catching AIDS in the medical community dissolved after many were tested and all came back negative except for the gay men. This also allowed doctors to assure the public that there was no risk of casual transmission from things like coughing and saliva. For medical professionals, the period of fear was for the most part over, and doctors could focus on treating and researching AIDS.

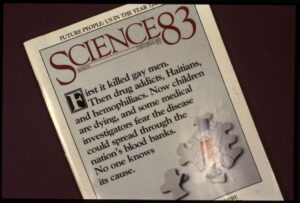

Photo: Cover of Science 83 with AIDS headline. (UC San Francisco, Library, Special Collections. Source: Calisphere)

Resources for Teachers

Student project: See the website by Ella S. Damty, based on the class assignment developed by UC Berkeley undergraduate research apprentice Corina Chen: Virus Hunters Newsletter: Obstacles in AIDS Research and Treatment

Education resources, including how-to for interviewing, tips for searching our collection, and the complete AIDS/HIV curriculum with sample assignments.

Seven-episode podcast: First Response: AIDS and Community in San Francisco.

All interviews in the AIDS Epidemic in San Francisco Oral History project.

High School Researcher on Social Biases: Obstacles in AIDS Research and Treatment

Guest high school blogger uses UC Berkeley Oral History Center interviews to write about Social Biases in AIDS Research and Treatment. This is part one of a 3-part series. Resources for teachers are at the end of the article.

Obstacles in AIDS Research and Treatment: Social Biases

by Ella S. Damty

Sophomore, El Cerrito High School

Early responses to the AIDS epidemic across the United States were slowed by biases against—and lack of concern for—the country’s gay communities. Many community leaders didn’t believe that a disease ailing homosexuals would affect their communities, and the methods of transmission (gay sex and IV drug use) made it appear to only affect people who engaged in illegal or, as some considered it, immoral behavior. In addition, the disease heightened stigma against homosexuals with names like gay cancer and GRID (Gay-Related Immune Deficiency), and made the gay community wary of public health officials. These social biases ostracized AIDS victims and made many public officials reluctant to act on their behalf.

One of the ways that public health officials tried to slow the spread of the disease was to spread information about it, with the help of local political leaders. But many of these politicians shrugged it off as something that wasn’t important or wouldn’t affect their communities. Dermatologist Marcus Conant, who first diagnosed Kaposi’s Sarcoma in AIDS patients and was involved in AIDS treatment and research since the epidemic began, recalls a meeting held to distribute pamphlets:

Ernie came to me that night and he said, “You won’t believe this. Most of the people just took it [the pamphlet] and kind of shrugged and walked off. One guy said, ‘Homosexuals?! We don’t have homosexuals where I come from!’” (Conant, 102)

Another obstacle to getting local leaders to take interest in treating the disease was that is was widely viewed as a law enforcement issue, because it was spread through gay sex and intravenous drug use, both of which were illegal activities at the time. As Conant explains it, “If you have this mindset, that this is a law enforcement problem, not a medical problem, then it’s not surprising that from the top all the way down there has been this constant resistance to do anything, to move (129).”

In addition to local leaders’ resistance to act on the issue, gay communities feared that the public health officials would use the disease as an excuse to curb their newfound freedoms. The gay community in San Francisco at the time saw the bathhouses as a symbol of gay liberation in the city. But it was also a hotspot for HIV transmission. Donald Abrams, a gay man treating AIDS, discusses the issue of closing the bathhouses from his perspective as a member of both groups.

But still, as a gay man and as a member of a group of people that had been persecuted from time immemorial, I also thought that in the absence of knowing what AIDS is really caused by and being absolutely certain that closing the bathhouses would have very wide-ranging repercussions, I saw both sides of the issue. The gay community had achieved a lot of liberation and a lot of prominence in San Francisco over the seventies and on into the early eighties, and I thought that closing the bathhouses would really be a political setback. (Abrams 46)

These biases against and from the gay community delayed the response to AIDS in San Francisco and around the country. The view of homosexuals as outsiders and criminals made public officials reluctant to act on their behalf, and made the gay community skeptical of their efforts when they did act.

Photo: The NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt panels displayed at San Francisco City Hall during San Francisco Lesbian and Gay Freedom Day Parade, 1988. (UC San Francisco, Library, Special Collections. Source: Calisphere)

Resources for Teachers

Education resources, including tips for interviewing, tutorial for searching our collection, and the complete Epidemics in History — AIDS/HIV curriculum with sample assignments.

Student project: See the website by Ella S. Damty, based on the class assignment developed by UC Berkeley undergraduate research apprentice Corina Chen: Virus Hunters Newsletter: Obstacles in AIDS Research and Treatment

Seven-episode podcast: First Response: AIDS and Community in San Francisco.

All interviews in the AIDS Epidemic in San Francisco Oral History project.

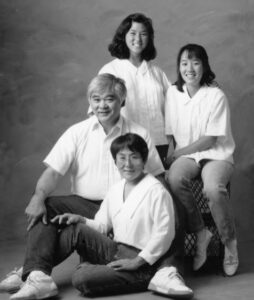

Janet Daijogo: Japanese Incarceration and Finding Her Place through Aikido and Teaching

by Deborah Qu

“I’ve actually heard that what you think of as your earliest childhood memory has a certain importance, but not because it’s necessarily your first memory. Just that having that association as your first memory means that you’ve placed a certain importance on it, for whatever that’s worth.” — Janet Daijogo

Janet Daijogo’s first real memory was the day military police knocked on her door and gave her family two weeks to relocate. It was during World War II, and she was Sansei or third-generation Japanese American. “The whole thing was just shrouded by fear,” she recalls during her oral history for The Bancroft Library in 2011. There was a fear of police knocking at her door and the uncertainty of where she was going to live. She realizes in retrospect that this memory was like a “body imprint” that influenced her personality, and something she carried with her into adulthood.

Janet Daijogo was born on March 21, 1937 in San Francisco, California. At age five, she and her family were relocated to incarceration camps at Tanforan Racetrack and Topaz, Utah, during WW2. Post incarceration, she followed in her mother’s footsteps and attended UC Berkeley. Today, Daijogo is a veteran kindergarten teacher at Marin Country Day school, having taught children for 40-plus years. She incorporates Aikido, a noncompetitive form of martial art, in her teaching, and attributes her journey in teaching and Aikido as a mental practice where she found her space and purpose.

Daijogo remembers moving to Topaz after a few months in Tanforan. Her parents carried on with hope or gaman, the belief in Japanese culture that they “can get through this kind of thing, and we do not complain.” While she does not remember much about Tanforan as a child, she recalls barracks with dirty wooden floors and sheetless cots, and mess halls with long waiting lines that served food on metal dishes. But Daijogo most distinctly recalls the large fences that encased the Topaz camp along the grey landscape, and how her imagination went wild about the people and mystery outside the fence.

After the war, the Daijogo family moved to Oklahoma. There, she remembers seeing black-white segregated bathrooms and being unsure about which one to enter. Daijogo recalls feeling divided, saying “I think at that moment . . . I realized that I was not one of them. I was not white, I was an outlier. I was somebody on the fringes.”

From fourth grade onwards through high school, Janet Daijogo lived on an American Army base in Japan. She describes the unfamiliarity about not knowing the language or dressing like her peers, and becoming more ‘Americanized’ in Japan. “There was this distance,” she remembers. “I did not really identify with them even though they looked like me.” Later, she looks back on her childhood and high school years by saying, “I think one of the themes of my life is being the outsider and finding the comfort of that, where to be, how to be in that situation.”

Janet Daijogo attended UC Berkeley, majoring in child development and minoring in history. Both her parents were Cal alumni and strongly valued education, but her mother was especially proud of attending Berkeley. Janet describes how “unusual” that her mom was able to attend Cal and how “it was also an important part of her identity.” Like many Berkeley students today, Daijogo felt the same excitement in anticipation for school. She describes the feeling of picking up books for the start of the semester, saying “there’s a real energy in them…like you’re getting ready to explore something out there.” But while Daijigo describes her experience as “amazing,” she also remembers thinking, ”oh my God, what am I doing here with all these smart people?”

After graduation, Daijigo and her new husband Sam moved to Japan, where she taught at an international school. While she still was seen as a foreigner, this time she experienced Japan more outside her American bubble. Once they returned to the US, Daijogo stayed at home to raise her children. However she quickly felt discouraged. She recalls that her “sense of purpose and personal value that comes from work” was missing, because she could not express her academic side. This was when she found a job at the Marin Child Development Center teaching emotionally disturbed children. First, she recalls coming home and crying every day for four or five months, frustrated at the difficulty of teaching children. Yet over time, Daijogo found there was something about these situations she had no control over. With the help of her mentor, Janet Daijogo realized that she was not the cause, but she also could not magically make them happy. She was just “part of the journey.”

Around this time, Janet Daijogo found Aikido. For Daijogo, Aikido was a space for reflection and grounding, where she found her “center, a place of stability and of ‘okayness’, of feeling good, of relaxation and of power.” She integrated the practice of Aikido into her teaching curriculum, and stressed the importance of cultivating a supportive relationship with oneself to students at a young age. Janet Daijigo discovered that she needed to treat herself in the same way she had taught the children; like them, she was “part of the journey.” Today, Janet Daijigo is a grandmother who still teaches at Marin Country Day and still practices Aikido. About accepting uncertainty and understanding the self, Janet Daijigo says, “I think at this stage in my life I now know what I know, and I know what I don’t know.”

This year marks the 150th anniversary of women being admitted to UC Berkeley on “equal terms as men,” as approved by the Board of Regents in 1870. Since the doors were opened that first year, there have been an innumerable number of accomplished women graduates from Berkeley who have gone on to contribute meaningful work in STEM and humanities, excel in sports, devote their lives to public service and communities, and introduce new and valuable perspectives on old patterns of thought. From looking at their outward accomplishments alone, it seems like large shoes for today’s students to fill. As a student studying remotely this year, I would not be surprised that many of us are anxious about school or future career prospects, health and wellbeing, financial issues, or the news in general. But Daijogo’s oral history stood out to me, because she openly speaks about the mental challenges of stressful life events and the importance of self care and patience. Her vulnerable story reminds us that that life is a journey of continued learning, and we are all along for the ride.

Deborah Qu is a sophomore at UC Berkeley and is majoring in psychology. As a research assistant for the UC Berkeley Oral History Center, she developed a collection guide to UC Berkeley Women Oral Histories, which is available on the Berkeley Women 150 and Oral History Center websites.

Read the Daijogo oral history: Janet Daijogo, A Life’s Journey: From Child of the Incarceration to Master Teacher, Translating the Truths of Aikido for the Kindergarten Classroom.

See the related oral history collection: Japanese American Confinement Sites.

Trial: Exeter Medieval Online ebook collection

UC Berkeley has a trial for Exeter Medieval Online (ebooks) through October 29th, 2020. The collection combines Liverpool University Press’s Exeter Medieval Texts and Studies and Exeter Studies in Medieval Europe print series, covering a chronological range of c.500-1500, with a broad European focus. The interdisciplinary collection includes monographs, guides, collaborative studies, edited volumes, and translations of important texts on the history, literature, and culture of the Middle Ages. The ebook collection provides full-text digital access to 83 titles, which can also be downloaded to PDF.

During the trial period, we have access to a 50-ebook subset of the collection. Logging in with a CalNet ID is required.

To use additional features, you can optionally create a personal account from the ‘Institutional Account’ tab. This will allow you to:

Highlight Text

Add bookmarks

Add/ download Citations

Add/ download Notes

Mark it as Favourite (but this is available from the “My Library” section)

Your feedback makes a difference! Tell us what you think.