Guest high school blogger uses UC Berkeley Oral History Center interviews to write about Fear in the Medical Community in AIDS Research and Treatment. This is part two of a 3-part series. Resources for teachers are at the end of the article, including the Oral History Center’s Epidemics in History—HIV/AIDS Curriculum.

By Ella S. Damty

Sophomore, El Cerrito High School

In the early years of the AIDS epidemic, no one knew what the disease was or how it was transmitted. This led to medical professionals who treated AIDS patients at San Francisco General Hospital to fear for their lives, not knowing whether they could get the disease themselves. This fear was particularly intense for gay health professionals, who were already in a high-risk group. This fear subsided for medical professionals once the HIV antibody test was developed in 1985, but in the years before that, fear plagued doctors and other health workers.

Doctors treating AIDS patients in the beginning didn’t use any protective measures when treating patients, including taking their blood for testing. Andrew Moss led the first epidemiological study of gay men with AIDS. On why health workers didn’t use gloves or other protective measures, he says, “Denial. We were refusing to acknowledge how afraid we were.” Moss went on to explain that despite the denial, the health professionals lived in fear.

We all thought we were going to die. By the middle of the next year, 1984, we all thought we were going to die. Volberding thought he was going to die. He was going around saying, “Oh, my lymphadenopathy is bad today.” He thought he had AIDS. He thought he had given it to his wife and his kids. Everybody did. I went to see my doctor five times. (Moss, 283)

Moss describes the period between 1983–1985, as “the true experience of terror.” During this time, he was working with patients, but the antibody test had not yet been developed. The lack of knowledge on who could get it or who had it was terrifying to health workers. “It was a period of maximum paranoia. Nobody knew who was getting infected (Moss, 283).”

Paul Volberding was an oncologist who first became involved in AIDS while treating patients with Kaposi Sarcoma. He created and worked in the AIDS clinic in San Francisco General. He describes the environment in his home during this period, and how when he developed any sort of sickness or fever, he thought he had AIDS, but wasn’t allowed to discuss it.

There was about a year or year and a half period where the anxiety was so great that AIDS was just not permitted as a discussion item at home. There was so much anxiety attached to it that if I’d say, “Gee, I’m worried about taking care of these patients. I’m worried I have a fever, maybe this is PCP,” my wife, Molly, wouldn’t let me talk about it. (Volberding, 122)

After the HIV antibody test was developed in 1985, all the health workers in the AIDS ward were tested, and most came back negative, except for some of the gay employees. At this point the fear was over for people like Volberding and Moss, married heterosexual men. But the risk remained for gay health workers, and Moss recalls several coworkers who ended up dying from AIDS, and informing them of their test results.

In January 1985, I tested myself, when I had seen how the results were coming in. All the heterosexuals were negative. It was a very difficult study to do. There were a lot of gay men working in the clinic, and one-third of them were positive. And they’re dead now. Philippe Roy, the receptionist, the Shanti social worker, Gary Starliper, and a whole bunch of people that worked there are now dead. We tested them and they were positive, and I had to tell them. (Moss, 283–284)

The fear of catching AIDS in the medical community dissolved after many were tested and all came back negative except for the gay men. This also allowed doctors to assure the public that there was no risk of casual transmission from things like coughing and saliva. For medical professionals, the period of fear was for the most part over, and doctors could focus on treating and researching AIDS.

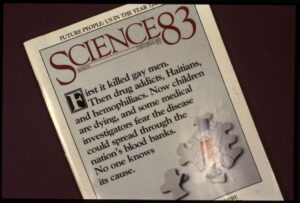

Photo: Cover of Science 83 with AIDS headline. (UC San Francisco, Library, Special Collections. Source: Calisphere)

Resources for Teachers

Student project: See the website by Ella S. Damty, based on the class assignment developed by UC Berkeley undergraduate research apprentice Corina Chen: Virus Hunters Newsletter: Obstacles in AIDS Research and Treatment

Education resources, including how-to for interviewing, tips for searching our collection, and the complete AIDS/HIV curriculum with sample assignments.

Seven-episode podcast: First Response: AIDS and Community in San Francisco.

All interviews in the AIDS Epidemic in San Francisco Oral History project.