Author: Roger Eardley-Pryor

H. Anthony (Tony) Ruckel: Sierra Club President 1992-1993, Pioneering Environmental Lawyer with Sierra Club Legal Defense Fund

New Sierra Club Oral History Project interview:

As a young lawyer, Tony Ruckel was just shy of his twenty-ninth birthday when, in the spring of 1969, he brought the nation’s first litigation under the 1964 Wilderness Act to the US District Court for Colorado. Ruckel and his plaintiffs—among whom included veterans from the US 10th Mountain Division, a wilderness guide, a local outfitter, the Town of Vail, Colorado Magazine, two local conservation organizations, and the Sierra Club—all believed the definition of wilderness set forth in the 1964 statute aptly described the acres adjacent a primitive area near Vail that the US Forest Service had proposed to sell for logging.

At the time, Ruckel had just moved back to Colorado, where earlier he had earned his undergraduate degree in Anthropology with an emphasis in Archeology due to his summer work at Pueblo Indian archeological sites in Mesa Verde National Park. Ruckel had returned to Colorado from Washington DC, where, in the 1960s, he marched in Civil Rights demonstrations, witnessed other historic events, and earned his J.D. from George Washington University Law School. It was in DC where Ruckel first joined the Sierra Club upon learning the Club was fighting against a government proposal to dam the Grand Canyon. By 1969, upon returning to Colorado, Ruckel represented the Sierra Club in court and in 1970 won his first major environmental law case, Parker v. United States (US District Court for Colorado, 1970). With that victory, Ruckel helped established an important legal precedent that ultimately enabled the designation and preservation of vast tracts of wilderness all across the United States.

Soon after, Ruckel founded and became director of the Rocky Mountain Regional Office for the Sierra Club Legal Defense Fund (SCLDF), one of the nation’s first public interest environmental law organizations, now named Earthjustice. From 1972 to 1986, Ruckel worked as the Rocky Mountain Regional Director and staff attorney for SCLDF, with responsibilities for litigation on areas stretching from the desert Southwest through the Northern Plains, including several of the nation’s premier national parks. Ruckel’s legal campaigns with SCLDF included battles against coal-fired power plants and resisting placement of a nuclear waste repository near a national park that could have threatened the downstream drinking water of the Colorado River from Utah to southern California.

Later, from 1990-1993 and 1996-1998, Ruckel was elected to and served on the national Sierra Club’s board of directors, which included his terms as Secretary, Treasurer, and from 1992 to 1993 as President of the Sierra Club. Additionally, through his service on the Sierra Club’s Investment Advisory Committee, Ruckel helped pioneer for environmental non-profits their financial investment in non-extractive industries. Throughout all of these endeavors, Ruckel advocated passionately for the protection of public lands and wilderness areas, while also regularly exploring those lands. Ruckel became an avid long-distance runner and is a rare mountaineer who has summited all fifty-four of Colorado’s 14,000-foot peaks.

In his oral history, part of the renewed Sierra Club Oral History Project, Ruckel discusses all of the above and more, including his family history, the exciting early years of environmental law, as well as organizational tensions between the national Sierra Club, the Sierra Club Foundation, and SCLDF. Tony Ruckel and I recorded his fifteen-hour oral history over five interview sessions in September 2019, all at his home in Denver, Colorado. I am delighted to now share his 369-page transcript here, which includes photographs from some of Ruckel’s ascents of 14,000-foot summits throughout Colorado.

Tony Ruckel’s oral history is significant for those interested in environmental history and United States history, particularly for his work helping pioneer the field of environmental law and his legal efforts in the 1970s to halt the construction of massive fossil fuel and nuclear energy projects in the Southwest. Additionally, from 1963 through 1968, Ruckel witnessed and participated in several historic events in Washington DC, including marching to the Lincoln Memorial and standing less than 100 yards from Dr. Martin Luther King during his immortal “I Have a Dream” address; standing in line for hours on a wintry November night waiting to pass President Kennedy’s catafalque in the Capitol Rotunda; attending Supreme Court arguments presided over by Chief Justice Earl Warren; as well as seeing significant parts of northeast Washington burn upon Dr. King’s assassination in April 1968.

Ruckel’s oral history also makes substantive contributions to the Sierra Club Oral History Project. In the late 1960s, for instance, Ruckel played a formative role expanding the Sierra Club’s East Coast activities. But most importantly, as the founder and director of the Rocky Mountain Regional Office for SCLDF, Ruckel played a significant role establishing and shaping the early evolution of environmental law. His narration here on friendships and legal campaigns with other pioneers of environmental law—like David Sive, Jim Moorman, Phillip Berry, Michael McCloskey, Richard Leonard, Leland Selna, Rick Sutherland, Beatrice Laws, and others—complements and supplements several existing interviews in the Sierra Club Oral History Project. And with regard the Sierra Club’s contemporary campaigns to combat climate change by ending the extraction and use of fossil fuels, Ruckel’s narrative of his legal battles against the Kaiparowits and Intermountain power plants reveals the Sierra Club’s surprisingly deep roots to move “Beyond Coal” several decades before that campaign’s formal designation. Additionally, as a nationally elected leader on the Sierra Club’s board of directors in the 1990s, Ruckel oversaw challenges to the Club’s organizational finances and relationships vis a vis the Sierra Club Foundation and the Sierra Club Legal Defense Fund. During his time on the board of directors, Ruckel also made significant contributions to ways that Sierra Club finances are invested, accumulated, and presented publicly.

Lastly, Ruckel’s oral history compliments The Bancroft Library’s significant collections related to the Sierra Club. In preparation for his interview, I read carefully Ruckel’s own book about environmental law and his career in it: Voices for the Earth: An Inside Account of How Citizen Activists and Responsive Courts Preserved National Treasures Across the American West (Samizdat Creative 2014). Ruckel kindly donated a copy of his book to The Bancroft Library’s permanent collection [Call number TD171 .R83 2014]. Additionally, just prior to Ruckel’s interviews, it so happened The Bancroft Library made publicly accessible numerous additions to its already large collection of Sierra Club Legal Defense Fund Records (BANC MSS 71/296 c, Sierra Club Legal Defense Fund Records, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley). The existing collection already included agendas, minutes, reports, clippings, financial reports, dockets, new matter forms, notes, and subject files, mostly pertaining to SCLDF’s now-infamous Mineral King litigation. In late July 2019, in preparation for Ruckel’s oral history, I met with Lisa Monhoff, the project archivist who processed The Bancroft Library’s new additions to the SCLDF collection. Monhoff explained how the new records range from 1967 to 1995 and include environmental litigation cases from more than 30 states and the District of Columbia, as well as amicus briefs for numerous cases, including some for the Supreme Court of the United States.

Ruckel then highlighted the following archival collections that complement sections from his own book on those topics, all of which he and I discussed during his oral history: Series 1: Administrative and Operational Files 1970-1991, Carton 3, folder 6: River of No Return Wilderness (Idaho) 1973-75, also covered in Voices for the Earth, pages 94-99; Series 3: Additions Received in 2009 1967-1995, Subseries 3.1: Environmental Litigation 1973-1995, Carton 9, folder 11: Colorado – Pitkin County 1991, also covered in Voices for the Earth, pages 116-121; Series 3: Additions Received in 2009 1967-1995, Subseries 3.1: Environmental Litigation 1973-1995, Carton 13, folders 14-15 – Circle Cliffs, Trans-Delta Oil and Gas 1973-1981, also covered in Voices for the Earth, pages 33-38. During his oral history, Ruckel and I discussed all of those topics and many more, including his work on cases related to managing the Grand Canyon (see Voices for the Earth, pages 49-65) and his efforts against the creation of a nuclear waste repository proposal next to Canyonlands National Park (see Voices for the Earth, pages 195-212).

Tony Ruckel’s gregarious nature and his storytelling made conducting his oral history a pleasure. The few days Ruckel and I shared together in September 2019 made me wish I could have joined him around the campfire out in some of the wilderness areas he helped preserve through his pioneering legal career. With the addition of Tony Ruckel’s oral history, the Sierra Club Oral History Project now includes accounts from well over one hundred volunteer leaders and staff members active in the Club for more than a century. Varying from only one hour to over thirty hours in length, these interviews document aspects of the Sierra Club’s diverse activities and concerns over the years, including protection of public lands and wilderness areas; attending to the “explore and enjoy” aspects of the Sierra Club’s mission through its robust outings program; safeguarding water and air quality; promoting sustainable energy and progressive climate policies; and working toward environmental justice. The full-text transcripts of all interviews in the Sierra Club Oral History Project, including this interview with Tony Ruckel, can be found online at the Oral History Center website.

— Roger Eardley-Pryor, PhD

H. Anthony (Tony) Ruckel, “H. Anthony (Tony) Ruckel: Sierra Club President 1992-1993, Pioneering Environmental Lawyer with Sierra Club Legal Defense Fund” conducted by Roger Eardley-Pryor in 2019, Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 2021.

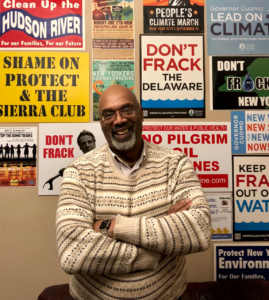

Bancroft Roundtable about Aaron Mair and the Sierra Club Oral History Project

At the recent Bancroft Roundtable on April 15, 2021, I had the honor of sharing the oral history journey I was lucky to experience in November 2018 while conducting a 15-hour interview with Aaron Mair, the Sierra Club’s 57th president and its first Black president.

The questions at the heart of my presentation were: How did the experience of conducting Aaron Mair’s oral history—first in South Carolina and then in Albany, New York—relate to the power of place and the importance of interconnection, two key themes that arose in Aaron’s oral history? And how has the enslavement and emancipation of Aaron’s ancestors, as well as his own life experiences, intersected with the Sierra Club’s evolving efforts toward environmental justice and its reckonings over race since the Club’s founding in 1892?

You can view my Bancroft Roundtable presentation here:

These informal Bancroft Roundtable talks bring together the campus community and the wider public to represent the fruits of research conducted at Bancroft. My interview with Aaron Mair occurred as part of the renewed Sierra Club Oral History Project, a collaboration now a half-century old that arose between the Sierra Club, one of the oldest and most influential environmental organizations in the United States, and the Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library, one of the world’s oldest organizations professionally recording and preserving oral history interviews. Over the past fifty years, this ongoing collaboration has produced an unprecedented testimony of engagement in and on behalf of the environment as experienced by individual members and leaders of Sierra Club.

Aaron Mair’s more-than two-decades of leadership within the Sierra Club has reflected a necessary and important process of change that the Club is currently experiencing, especially on issues regarding race—both with regard to the Sierra Club’s long history and for its future. I’m delighted I had the opportunity to meet Aaron and to record his life story so that others, in the future, can learn his lessons, especially as they relate to this present moment.

With regard to the power of place, Aaron Mair’s sense of self and his sense of place are deeply entangled. To nourish one’s sense of place, to acquire the sense not of ownership but of belonging, fellow Sierra Club member Wallace Stegner suggested in an essay titled “The Sense of Place” that we look around us instead of always looking ahead. Oral historians like myself typically help narrators look back and reflect on their past. However, the intense week I spent with Aaron Mair while recording his fifteen-hour oral history helped me realize how much we can learn by joining our narrators in looking around.

Aaron draws strong connections between his ancestry as a Black American and his intersectional activism for justice. And what Aaron describes as his “culture, custom, and heritage” all grow directly from particular places. Those places, in turn, have shaped Aaron’s sense of justice, his demands for equity, and his sensibilities toward environmental stewardship. In my Bancroft Roundtable talk, I shared my own experiences of visiting places with Aaron that he considers central to his own life story.

I also hope that sharing this behind-the-scenes perspective of my interview experiences with Aaron enabled consideration on the praxis of oral history, particularly to the potential importance of a narrator and an interviewer sharing embodied experiences situated in a particular place—or, in this case, particular places—notably in places the narrator finds meaningful. That embodied experience might be especially important between a white interviewer and a Black narrator. At least, I certainly found it to be important in my interview experience with Aaron Mair. The powerful places that Aaron shared with me, and the enlightening experiences they enabled for his oral history interview might raise new questions for our new era of conducting oral history interviews over Zoom. Namely, what might be lost when a narrator and interviewer no longer experience together the embodied and shared-place aspects of conducting an oral history together?

Nancy Donnelly Praetzel: Tales from Marin County

New oral history: Nancy Donnelly Praetzel

Nancy Donnelly Praetzel’s oral history documents a century of lived history in Marin County as told by a 1953 graduate of UC Berkeley. Praetzel, who has researched her family’s genealogy, discussed several generations of her family who have lived in Marin County from just after the 1906 earthquake through the present. She shared her family’s stories of migration to and survival in Marin County, including that of her English-born grandfather, Ernest Clayton, who made beautiful paintings of California wildflowers that she still sells today. Praetzel also recounted her own memories of the Great Depression, of life on the Homefront during World War II, of youth summer camps in Sonoma County, as well as her experiences at UC Berkeley in the early 1950s. Praetzel offered insight into the nature of work as a stewardess in the commercial airlines industry of the mid-1950s. She also discussed her marriage from 1957 through today to fellow UC Berkeley graduate, Robert Praetzel, with whom she raised four children in Marin County. Nancy Donnelly Praetzel’s oral history provides a snapshot of one woman’s experience from what Tom Brokaw popularized as the “Greatest Generation.”

Nancy Donnelly Praetzel was born on September 30, 1931, in Marin County, California. Her maternal grandparents came to the Bay Area, respectively, from Ireland and England. Both her maternal and paternal grandparents met in San Francisco and moved to Marin County after destruction of their homes in the 1906 earthquake. In the 1930s, Praetzel’s British maternal grandfather, Ernest Clayton, began painting wildflowers he collected while hiking in Marin County, the original prints of which he donated to the San Francisco Public Library. Nancy Praetzel later resurrected these prints from the archives, hosted various gallery showings of her grandfather’s art, and now sells his prints online.

Upon completing grammar school and high school in Marin County, Praetzel attended UC Berkeley from 1949 to 1953 where she joined the Delta Delta Delta sorority and majored in Social Welfare. Upon graduation, Praetzel worked in Marin County for the Camp Fire Girls, the first nonsectarian, multicultural organization for girls in America. From 1955-1957, Praetzel worked as a United Airlines stewardess, including a stint traveling with the DC Press Corps during Dwight D. Eisenhower’s 1956 re-election campaign. In 1957, she married Robert Praetzel, a fellow UC Berkeley graduate whom she met on campus seven years earlier. They have been married over six decades and live in the same home, nestled among redwood trees on the slope of Mt. Tamalpais, in Kentfield, Marin County, California, where they raised their four children. The appendix to Nancy Donnelly Praetzel’s oral history includes newspaper clippings from her time at Cal, examples of her grandfather’s wildflower prints, and several family photographs from Praetzel’s long, rich life.

I wish to thank Nancy Praetzel and her husband Robert for their patience this past year as we adjusted to the pandemic-induced realities of remote work while finalizing their oral history interviews. I also want to thank the anonymous donor whose generous gift to the Oral History Center made these interviews possible.

—Roger Eardley-Pryor, PhD

Robert Praetzel: Marin County Lawyer Who Stopped Marincello

New oral history interview: Robert Praetzel

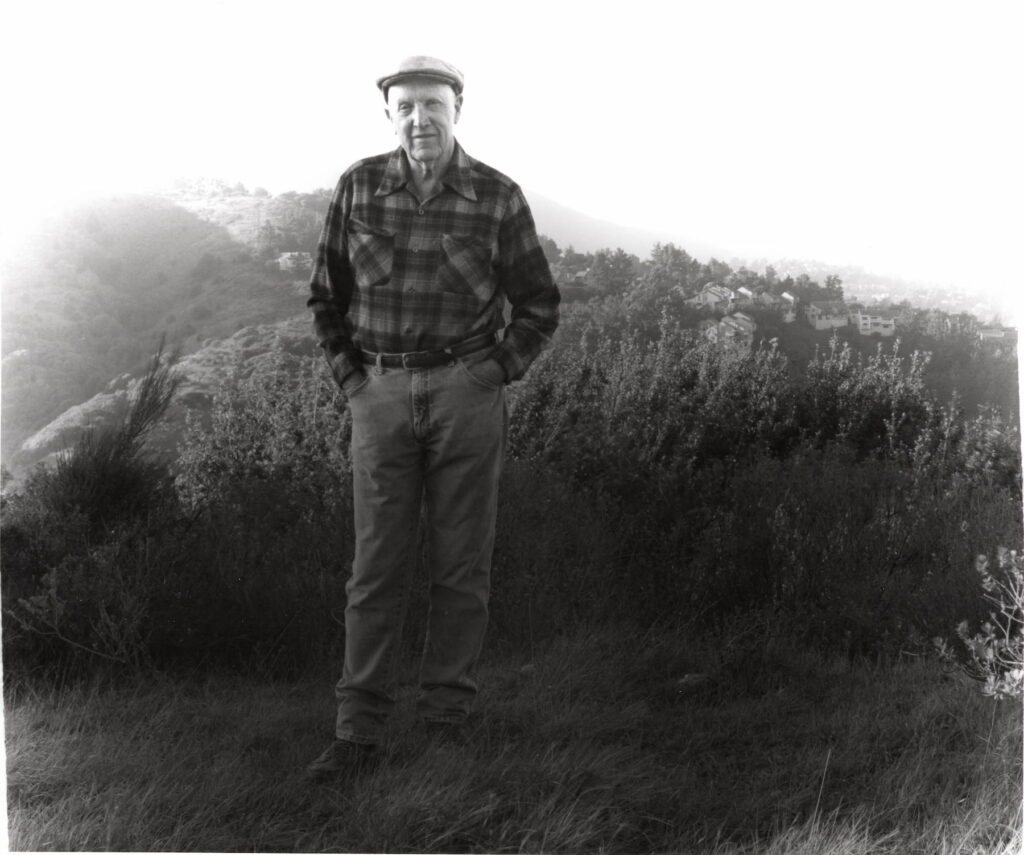

for the book Legacy: Portraits of 50 Bay Area Environmental Elders

with text by John Hart, published by Sierra Club Books in 2006.

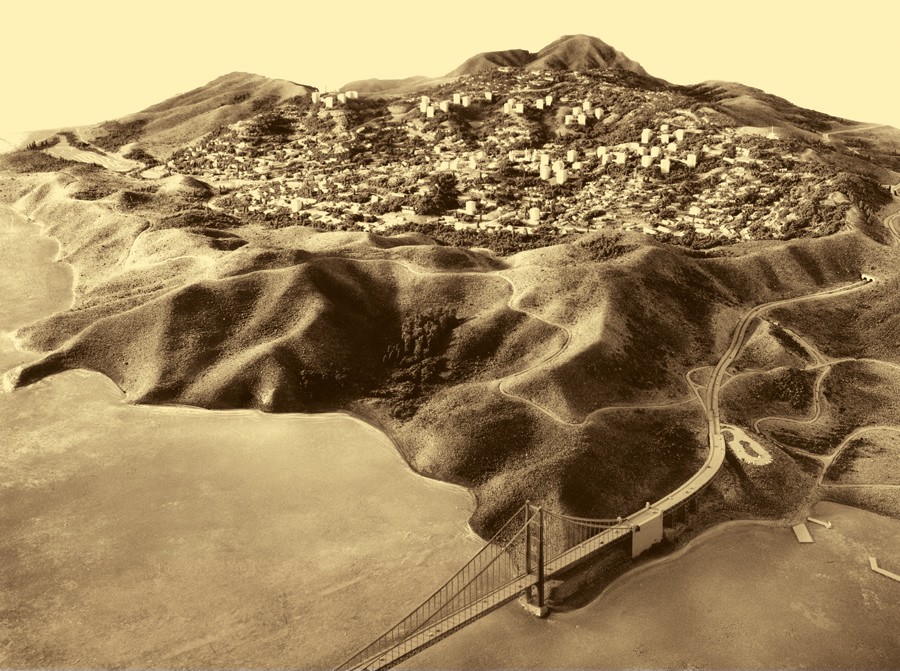

Robert Praetzel, a World War II veteran and graduate of UC Berkeley in 1950, is the Marin County lawyer responsible for stopping Gulf Oil’s Marincello real estate development in the late 1960s. The Marincello project would have built from scratch a new city in Marin County for some 30,000 people housed in fifty apartment towers, numerous single-family homes, low-rise apartments, and townhouses on 2,100 pristine acres in the Marin Headlands area. Today, thanks to Robert Praetzel’s fastidious and pro-bono legal work from 1966 through 1970, those lands are now preserved within the Golden Gate National Recreation Area. Praetzel and I recorded his four-hour-long oral history in the spring of 2019 at his home, nestled among the redwood trees on the slope of Mt. Tamalpais in Kentfield, Marin County, California. Praetzel’s 127-page transcript, complete with family photographs, adds important details to the broader story of how two major American cities, San Francisco and Oakland, came to have such exceptional tracts of preserved national park lands just minutes away from their urban centers.

preserved as Gerbode Valley in the Marin Headlands area of the Golden Gate National

Recreation Area.

Prior to recording Praetzel’s interview, the Oral History Center’s archives included a multi-narrator volume on Saving Point Reyes National Seashore, but not on the substantial Marin Headlands area that Praetzel helped preserve. Our oral history archive also includes previously recorded interviews with Martin Rosen, a conservation lawyer who worked in conjunction with Robert Praetzel; with Martha Gerbode, the philanthropist who helped purchase and preserve the land that Praetzel saved from development for inclusion in the Golden Gate National Recreation Area; as well as a Sierra Club oral history volume focused on the San Francisco Bay Area that references the Marincello real estate project that Praetzel defeated. Now, with the inclusion of Robert Praetzel’s oral history, the Oral History Center collection includes details of his dogged and pro bono legal efforts to preserve the Marin Headlands from the Marincello project, which also called for a “landmark hotel” atop the highest point in the Headlands as well as 250 acres for light industry, a mile-long mall lined with reflecting pools, and a square full of churches called Brotherhood Plaza. In the late 1960s, Robert Praetzel played an essential role in legally stopping this development project in what is now preserved as the Gerbode Valley and managed by the US National Park Service.

Robert Praetzel’s oral history also offers recollections from his youth in Marin County during the Great Depression (including eating a squirrel that his father hunted one Thanksgiving); his Navy service during World War II aboard a tanker-boat carrying highly explosive aviation fuel across the Pacific Ocean; his experiences as a student at UC Berkeley and UC Hastings College of Law in the late 1940s and early 1950s; as well as his marriage to fellow Berkeley alumnus, Nancy Donnelly Praetzel, with whom he raised a family in Marin County, all while building his eclectic legal career. In addition to detailing his victory against the Marincello development, Praetzel shared other stories from his legal career. One of those stories recounts his pro bono representation of environmental activists in 1969 who were arrested for obstructing logging trucks from felling a grove of redwood trees along the Bolinas Ridge in Marin County. Local newspaper clippings about the case are included in the appendix to Praetzel’s oral history, along with several photographs from Praetzel’s long, rich life.

I wish to thank Robert Praetzel and his wife Nancy Donnelly Praetzel for their patience this past year as we adjusted to the pandemic-induced realities of remote work while finalizing their oral history interviews. I also want to thank the anonymous donor whose generous gift to the Oral History Center made these interviews possible.

—Roger Eardley-Pryor, PhD

Of Molecules & Oral History: Script Review of NOVA’s “Beyond the Elements”

On March 12, 2020, an email arrived asking me to review three final scripts for the science series NOVA, the most-watched prime time science series on television with nearly five-million weekly viewers. Nearly a year later in February 2021, I’m delighted to see those NOVA episodes premier on PBS as the three-part series “Beyond the Elements.” The first episode focused on molecular Reactions, the next on virtually Indestructible molecules, and the third episode explored molecules of Life. Watching these episodes and reading my name in the credits as a “Science Advisor” for NOVA was thrilling.

But let’s be honest: after this past year, I’m delighted to have thus-far survived the pandemic and everything else that 2020 threw at us! From shelter-in-place to shuttered businesses, from Zoom meetings to elbow-bump greetings, from wild fires to fascism, and from righteous calls for racial justice to right-wing mobs denigrating our democracy, it’s been one hell of a year. Watching these NOVA episodes on PBS offered me a reminder of all that we’ve experienced since March 2020 when I received that email to review NOVA’s final scripts. Reflecting on this past year, I now see how working on those NOVA episodes helped me to muddle through that difficult time last spring. It re-inspired my fascination with science as well as my passion for oral histories with wondrous people, several of whom do the fascinating work of science. Reviewing those scripts also helped me imagine a future beyond the then all-consuming pandemic.

What are your memories of March 2020? Mine are saturated in fear. I recall dizzying levels of anxiety. Focused concentration felt nearly impossible. So much seemed unknown in March 2020, but we knew enough to be scared. We knew a novel virus that emerged in China was spreading rapidly around the world, and especially, by then, throughout the Bay Area here. We knew of no medical treatment to stop its spread or its effects. And we knew many people would not survive this new disease. For me, fear of what we did know as well as what we did not know felt crippling. Yet in my inbox appeared that email reminding me quite kindly of my earlier agreement to continue reviewing and advising on these three NOVA scripts. They asked: would I be able to return my reviews in the next two weeks? I thought: would my family and I even be alive in two weeks? At least, that’s where my mind was at in March 2020. Even so, I agreed to return my edits as quickly as I could—perhaps as a kind of pandemic denial, a naive attempt to reclaim normalcy.

As it happened, reviewing those scripts was both interesting and inspiring. Interesting, of course, because NOVA’s episodes of “Beyond the Elements” are captivating. The shows build from NOVA’s earlier special episodes on hunting atomic elements with these new episodes exploring the key molecules and chemical reactions that have shaped and continue to shape our lives and the universe as we know it. David Pogue hosts these episodes in his adventurous and cheeky way with excellent demonstrations and explanations by leading scientists, all accompanied by beautiful graphics and special effects. These stories about nature’s most fascinating molecular interactions are delightful, as are the scientists themselves who tell those stories.

As it happened, reviewing those scripts was both interesting and inspiring. Interesting, of course, because NOVA’s episodes of “Beyond the Elements” are captivating. The shows build from NOVA’s earlier special episodes on hunting atomic elements with these new episodes exploring the key molecules and chemical reactions that have shaped and continue to shape our lives and the universe as we know it. David Pogue hosts these episodes in his adventurous and cheeky way with excellent demonstrations and explanations by leading scientists, all accompanied by beautiful graphics and special effects. These stories about nature’s most fascinating molecular interactions are delightful, as are the scientists themselves who tell those stories.

To my surprise, reviewing those scripts last spring also gave me hope and helped lift me out of my initial, deep COVID despair. After prior years of commenting on and reviewing iterations of scripts for “Beyond the Elements,” that last round of edits in March 2020 arose at a difficult time. But that work helped ground me with a higher purpose and a commitment to others. It enabled my imagining of a future when this NOVA series would finally broadcast to millions of viewers. It helped move me beyond my immediate fears during that harrowing March of 2020. And it helped me, as an oral historian, to re-engage in our sacred project of building knowledge and sharing it through engaging narratives.

Upon submitting my review of the NOVA episodes, I found renewed purpose for sharing our own delightful stories about science as told by our fascinating oral history narrators. My colleagues in the Oral History Center all re-committed to our ongoing projects that spring and summer. Pandemic notwithstanding—very much in spite of it—we adjusted to our newly required remote-working situations, and we adapted our work flows, our fundraising, and our interviewing to not just survive this pandemic, but to find and create meaning during it. And through our collaborations, we even finalized a few of our own oral histories that, like NOVA’s “Beyond the Elements,” explore the interactions of molecules.

By August of 2020, we published my fifteen-hours-long interview with Alexis T. Bell, the Dow Professor of Sustainable Chemistry in UC Berkeley’s Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, who is a world-renowned leader in catalysis and chemical-reaction engineering. In September 2020, Paul Burnett published his detailed oral history with John Prausnitz, a professor since 1955 in Berkeley’s Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, who helped pioneer the field of molecular thermodynamics. And in October of 2020, we published my oral history with Michael R. Schilling, a chemist in Los Angeles at the Getty Conservation Institute who specializes in new and complex methods for analyzing the molecules in materials used by artists and art conservators.

For me, that work last spring on NOVA’s “Beyond the Elements” helped me discover a way to move beyond the pandemic. It helped refocus my privilege and pleasure in recording, preserving, and sharing the life stories of our oral history narrators. And while I wish our struggles with this ongoing pandemic were over, I’m very pleased to see all that we’ve accomplished this past year in the Oral History Center. Back in March 2020, when reviewing those final scripts for NOVA, I imagined the episodes would eventually premier at a time when the world had returned to “normal,” whatever that meant. As it happened, the episodes’ premiers in February 2021 occurred amidst our continued pandemic, which has lasted so long it seems to have become our new normal. Even if our slow and sad dance with COVID-19 continues, I’m very pleased to have seen “Beyond the Elements” broadcast on PBS and to be listed as a “Science Advisor.” And I’m equally grateful for the lessons those episodes taught me, both about the science of molecular interactions but especially on the importance of meaningful endeavors during difficult times.

— Roger Eardley-Pryor, PhD

Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library

Aaron Mair: Sierra Club President 2015-2017, on Heritage, Stewardship, and Environmental Justice

New Sierra Club Oral History Project interview: Aaron Mair

Aaron Mair is a pioneer in environmental justice and became the first African American president of the Sierra Club from 2015-2017. Mair, whose ancestors suffered enslavement, has dedicated much of his life to overturning the ongoing injustices experienced by Black Americans, including environmental racism. The Power of Place, Mutuality, and Interconnection all arose as important themes throughout Mair’s fifteen-hour oral history, which we conducted over five interview sessions in November 2018, first in Pickens County, South Carolina, and then in Albany, New York, where Mair lives. That week that Aaron Mair and I shared together became one of the most enlightening and powerful experiences in my life as an oral historian.

On the day we first met in South Carolina, just before his first interview session, Mair walked me through an unkept graveyard where his mother’s enslaved ancestors are buried. A few days later, on our final day of interviewing, we walked through snow across the Helderberg Escarpment that rises above the Hudson Valley in New York, near where Mair has lived most of his life. As he informed me, the Helderberg Escarpment is the site where, over 150 years earlier, a Southern slave-owner named Joseph LeConte studied geology with Louis Agassiz and nurtured notions of scientific racism. After the Confederacy collapsed, Joseph LeConte moved west to become a geology professor at UC Berkeley and co-founded the Sierra Club alongside John Muir in 1892. Nearly 125 years later, in 2015, Aaron Mair became the Sierra Club’s 57th president and its first African American president.

Aaron Mair was born in November 1960. He completed PhD coursework in Political Science at the State University of New York at Binghamton University, and upon becoming a father, he departed as ABD to work for the New York State Department of Health in Albany, where he still works as an epidemiological-spatial analyst. By the late 1980s, Mair’s training in geographic information systems, his graduate readings in World Systems Theory, and his family’s experiences in civil rights and labor organizing all came together in Mair’s campaign to shut down the toxic ANSWERS (Albany New York Solid Waste to Energy Recovery System) incinerator in Arbor Hill, the majority Black neighborhood where Mair and his family lived. The ANSWERS incinerator, which burned trash to produce electricity for the Empire State Plaza where Mair worked, also produced toxic ash that blew directly onto Mair’s family and community. In 1998, after a decade-long battle to close the incinerator, Mair won a landmark $1.4 million settlement with New York state (his employer) for environmental racism. He then used those funds to further his intersectional environmentalism by founding two non-profit organizations: Arbor Hill Environmental Justice Corporation, and the W. Haywood Burns Environmental Education Center. Through these organizations, Mair advocated further for environmental justice, including in the Clean Up the Hudson campaign that forced General Electric to dredge toxic PCBs from the Upper Hudson River.

In 1999, Mair joined the Sierra Club in a conscious effort to reform it from the inside. Years earlier, while still battling the toxic ANSWERS incinerator, Mair sought to partner with the Sierra Club’s Atlantic Chapter in New York City. Instead, the all-white room of Sierra Club members rejected Mair’s overture and said, “Did you check with the NAACP?” However, Albany’s local Sierra Club group did scrounge up early support for Mair’s campaign. With gratitude, Mair vowed that once he successfully closed the ANSWERS plant, he would join the Sierra Club to ensure it would collaborate with communities of color. Upon joining the Sierra Club, Mair held leadership positions at every level, including as group chair, then chapter chair and environmental justice chair in the Atlantic Chapter in New York; as national chair of the Sierra Club’s Diversity Council and of its National Environmental Justice and Community Partnerships; as an elected member to the national Sierra Club board of directors; and as president of the Sierra Club from 2015-2017. Mair became instrumental in creating the Sierra Club’s new Department of Equity, Inclusion, and Justice. Today, he continues to serve as a nationally elected member to the Sierra Club’s board of directors.

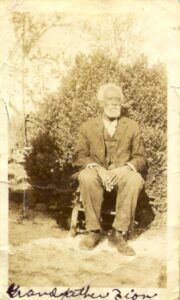

For his Sierra Club Oral History Project interview, Mair insisted we conduct his first interview sessions at the Hagood Mill Historic Site in Pickens County, South Carolina, in part to connect his family’s heritage of enslavement, emancipation, and environmental stewardship there to the life of Confederate slave-owner, Sierra Club co-founder, and UC Berkeley professor Joseph LeConte. (In November 2020, UC Berkeley officially removed the name LeConte Hall from its Physics Department building on campus.) According to a historic marker at the Hagood Mill Historic Site, the mill was reconstructed in 1845 by James Hagood, a prominent “planter and merchant” in South Carolina, who served in the state’s House of Representatives. Nothing at the Hagood Mill Historic Site mentioned how Hagood’s money and influence derived from his family’s chattel enslavement of humans, including Aaron Mair’s ancestors. The Mill’s construction occurred shortly after the birth in 1844 of Zion McKenzie, Mair’s great-great maternal grandfather whom the Hagood family enslaved. During his time as Sierra Club president, Mair made that discovery of who, exactly, had enslaved his family after years of deep genealogical research. Documents and photographs from Mair’s genealogical research and his years of activism can be found in the appendix to his oral history.

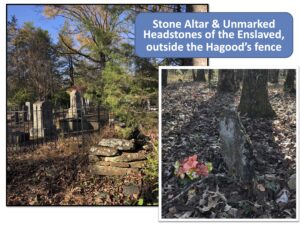

Before Mair and I began recording his first interview session, he showed me another unaccounted legacy of his family’s history at the Hagood Mill Historic Site. Together, Mair and I visited the “slave section” of the Hagood cemetery in an unkept pocket of land directly next to the well maintained Hagood family cemetery. In contrast to the Hagood family’s ornate headstones and sarcophagi, replete with crosses for Confederate veterans and bounded by a wrought-iron fence, the graves of Mair’s enslaved ancestors were barely noticeable among the fallen leaves. They were marked only by unhewn river rocks set slightly askew as nameless headstones. In that moment, Mair spoke solemnly about the generations of lives lost to slavery, about its ongoing aftereffects, and about the power of public memorials, especially the impact of what is not memorialized.

Mair then pointed to a nearby collection of large stones stacked against a tree to form a roughshod alter. He named the alter as the site of the first Golden Grove Church, the later iterations of which Mair and his family still attend today. Mair spoke then about the importance of faith for his family, and he offered up a prayer before we returned to the Hagood Mill to begin his oral history. Much of Mair’s first interview that day recounted the evolution of his enslaved ancestors’ emancipation from human dominion to their sustainable stewardship of the land where, today, the homes of his South Carolina relatives and the Golden Grove Baptist Church still stand. Those stories about Mair’s ancestors helped to contextualize his own conceptions of environmental responsibility, which later inspired his pioneering work in environmental justice and his leadership within the Sierra Club.

Mair and I completed his final oral history sessions in Albany, New York, in the historic and majority Black neighborhood of Arbor Hill where Mair lived and raised his daughters for many years. During his interviews in Albany, Mair shared stories of his intellectual awakenings in college, the beginnings of his civic and environmental activism in Albany, his pioneering work in the environmental justice movement, and his more-than-twenty-years of effort to help the Sierra Club build bridges across the civil rights, labor rights, and environmental rights movements. Just down the street from one of our interview locations, Mair pointed out the ominous smokestacks rising up from what once was the ANSWERS solid waste incinerator. Mair’s decade-long battle to stop that incinerator from spewing toxic ash onto his family and community changed his life. In the process, Mair became active on so many issues in Albany that it proved impossible for us to record all those stories. However, the patterns I saw in his activism included reclaiming open space for public use, demanding equal treatment by law, ensuring his community’s political voice was heard, fighting toxic pollution, and seeking just recompense from those who’ve done wrong. In many ways, Aaron Mair’s life history, and that of his family, reflect the Sierra Club’s own increased awareness and historical evolution to better incorporate equity, inclusion, and justice in its environmental efforts.

On our final day together, during his lunch break, Mair met me in the Helderberg Mountains just outside of Albany. A light snow blanketed the ground as we walked across the escarpment and looked over the Hudson Valley. The rock and fossil records at the Helderberg Escarpment are so extensive and well-exposed that the site became pivotal to the study of North American geology in the early nineteenth century. Charles Lyell, the foremost geologist of that era, read from his home in England the newest research then done on those rocks just outside of Albany. When Charles Darwin read Lyell’s Principles of Geology (1830-33), it helped Darwin conceive of evolution as a slow process in which small changes gradually accumulate over time. While at the Helderberg Escarpment, Mair reiterated how, in the mid-nineteenth century, Joseph LeConte—a co-founder of Sierra Club in 1892 and a former slave-owner from South Carolina—conducted geological research at that very site with Harvard geologist and white supremacist Louis Agassiz. More than once that week, Aaron suggested how his recent presidency of the Sierra Club, when contextualized by his own life and heritage—including his family’s history of enslavement and emancipation—signified a kind of evolution for the Club, perhaps for the broader environmental movement. Hopefully, both. Mair and I concluded his oral history that evening with an epic interview session that lasted seven hours. We emerged to find Albany blanketed in four inches of fresh snow.

By the time I landed back in San Francisco the following day, the then-deadliest and most destructive fire in California’s history, the Camp Fire, had already decimated the town of Paradise and, over the next week, continued scorching some 240 square miles of land, taking with it many people’s lives and livelihoods. Ash from that horrific fire rained down on my wife, myself, and our one-year-old daughter in Sonoma County, even though we lived more than 150 miles from the inferno. Smoke from the blaze made the Bay Area’s air quality the worst of any place on the planet and rose to levels federally designated as dangerous. The hazardous air and unavoidable soot falling on my family made me think of Mair’s efforts to stop the ANSWERS incinerator from raining toxic ash on his children. And it reminded me how current Sierra Club campaigns against climate change are, in some ways, efforts toward climate justice for us all, but especially for our children and Earth’s future generations.

Aaron Mair’s oral history is part of the Sierra Club Oral History Project, a longstanding partnership between the Sierra Club and the Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library that began soon after the first Earth Day in 1970. For fifty years now, the Oral History Center has partnered with the Sierra Club to produce, preserve, and post for free online an unprecedented testimony of engagement in and on behalf of the environment, as told by well over one hundred volunteer leaders and staff members active in the Club for more than a century. However, few of those interviews in the Sierra Club Oral History Project share stories of the Club’s evolution toward environmental justice. The publication of Mair’s interview begins to fill that lacuna, and I hope we can record more powerful stories from Sierra Club members and staff leaders who, similarly, helped move the Club on issues of environmental justice. In his interview, Mair revealed how his life experiences and ancestry intersected with the Sierra Club’s evolving efforts on diversity, inclusion, and justice. Many more stories from that journey need to be shared. I’m deeply grateful Aaron Mair shared his story with me.

— Roger Eardley-Pryor, PhD

You can read Aaron Mair’s oral history here:

For related work in the Oral History Center’s renewed Sierra Club Oral History Project:

See our oral history of Michele Perrault, who became the first female president of the Sierra Club in its modern era, twice elected as national president from 1984 to 1986 and from 1993 to 1994.

See this post on Intersectional Progress through Women in the Sierra Club, which highlights research by Ella Griffith (UC Berkeley Class of 2020) on “Sierra Club Women” — an annotated bibliography of women’s oral histories conducted between 1973 and 2018 for the Sierra Club Oral History Project.

Michael R. Schilling: Chemical Analysis of Art at the Getty Conservation Institute

New oral history release: Michael R. Schilling

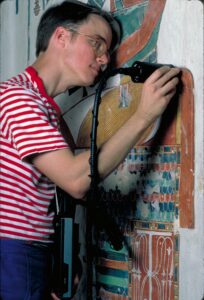

Michael R. Schilling is a chemist and the head of Materials Characterization in the Science Department at the Getty Conservation Institute (GCI), which works internationally to advance conservation practices in the visual arts—broadly interpreted to include objects, collections, architecture, and sites. Since joining the GCI in 1983, Schilling worked on two of the GCI’s flagship world-heritage-site conservation projects: the 3,200-year-old wall paintings in the Tomb of Queen Nefertari in the Valley of the Queens, near Luxor, Egypt; as well as Buddhist paintings in Cave 85 of the Mogao Grottoes located along the ancient Silk Road caravan routes in northwestern China. More recently, Schilling has specialized in developing and teaching new and complex instrumental methods for analyzing the chemistry of materials used by artists and art conservators—from the chemicals in Willem de Kooning’s paints, to the different kinds of plastics in Walt Disney’s animation cels, to the various species of tree saps used in Asian lacquers that were then applied to wood on 18th-century French furniture.

Throughout his oral history, Schilling shared lively stories from his career as a chemist in all three of the GCI’s historic locations while also discussing his family background, his education, the influence of key mentors, as well as the importance of his Christian faith to his marriage and fatherhood of two children. Schilling addressed how he reconciles his Christian faith with his career as a research scientist and rejects the notion of an inherent conflict between science and religion. Schilling’s oral history, which recorded nine hours of dialog across four interview sessions all conducted in April 2019, produced a 234-page transcript that includes an appendix with family photographs and images from Schilling’s work in the GCI.

Michael R. Schilling was born on December 4, 1957 in Los Angeles, California, where he has lived his entire life. Schilling was the first in his family to complete college and earned both his Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees in Chemistry at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona. Schilling married Cherrie Carr in 1982, and they welcomed to the world their children Nicolas and Kate in 1985 and 1988, respectively. In 1983, Schilling began work in the GCI as an Assistant Scientist. He remains the only Getty staff member who worked in all three GCI locations: at the Getty Villa laboratory near Malibu; at the Marina del Rey facility near Venice Beach; and now at the beautiful Getty Center in the Brentwood hills, which includes the GCI’s Materials Characterization laboratory that Schilling now oversees.

In addition to detailing the history of art and its curation for the Getty Trust Oral History Project, Schilling’s interview contributes to the Oral History Center’s vast collection on science and technology. In particular, Schilling described—in accessible layman’s terms—his creative use of pyrolysis–gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (or Py-GC/MS), which rapidly heats a sample to produce small molecules that are then separated and identified by their weight. Schilling outlined a few high-profile examples from his Py-GC/MS process development, including the chemical analysis and therefore improved preservation of aged and peeling Walt Disney animation cels; the analysis of modern paints, particularly those mixed by Dutch-American artist Willem de Kooning for his abstract expressionist works; and especially Schilling’s contributions to new and minimally invasive methods for identifying and analyzing the surprising diversity of tree saps used in Asian lacquers for wood that French furniture-makers adored in the 1700s. The latter project for analyzing Asian lacquers has garnered Schilling and his colleagues international renown from curators and conservation scientists in leading art institutions around the world, from Paris to Beijing.

As a conservation scientist, Schilling discussed the intricate analysis tools he assembled to help interpret Py-GC/MS data for his tripart collaborations with art conservators and with art historians/curators. During his oral history interview, Schilling likened their tripart work in cultural heritage to a three-legged stool:

“Curators and art historians are one leg of the stool. They understand the artist, the environment that he or she was in, attitudes and motives and meanings, the life story of the artist, and traumas that artists go through that affect the art that they make. … What they contribute, then, provides incredible depth and breadth to a study of a particular artist. … [The] Conservator, then, is—they’re artists in their own right, they’re studio artists. They work to preserve, clean, protect works of art. That’s their job. … [They] try out potential cleaning methods, treatment methods, dirt removal—things like that. Then again, they need to know—to do the best job—they need to know the chemistry of what it is that they’re treating. That’s when they come to conservation scientists like me.

Art history, conservation, conservation science—we all work together to understand cultural heritage better. We’re each bringing our own unique backgrounds and perspectives and points of view to bear when we’re sitting in front of a work of art, saying ‘Let’s understand it better.’ … So, understanding the art and how it was created, why it was created, where it was created, for what reason is important. Understanding how it’s changed, what its chemistry is, what’s happening right at the surface where a lot of the conservation treatments happen—that’s necessary in order to come up with and devise a safe and ethical treatment that can be applied to protect it, and restore some of its original appearance, make it more durable, last longer for future generations. You need all of that knowledge to really tell the entire story of an object or an artifact.”

We are very pleased to now publish Michael R. Schilling’s oral history. Many thanks to the J. Paul Getty Trust, which partnered with the Oral History Center in 2015 to establish the ongoing Getty Trust Oral History Project. This joint venture is part of the Getty’s broader mission to expand knowledge and appreciation for art. One of several foci of the Getty Trust Oral History Project features interviews with longtime Getty staff members, art conservators, as well as trustees who made significant contributions to the field and had an impact on the direction of the Getty Trust, often at pivotal moments. Michael Schilling exemplifies a longtime Getty staff member who continues to make significant contributions to his field of conservation science.

You can read Michael Schilling’s interview here:

— Roger Eardley-Pryor, Ph.D.

Alexis T. Bell: A Career in Catalysis and University Administration at UC Berkeley

Alexis T. Bell — new oral history release

Alexis T. Bell is the Dow Professor of Sustainable Chemistry in the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering in UC Berkeley’s College of Chemistry. At Berkeley, Bell became an internationally recognized leader in heterogeneous catalysis and chemical-reaction engineering who helped pioneer the development and application of spectroscopic methods to elucidate catalytic processes, as well as the application of experimental methods in combination with theoretical methods. Bell’s extensive oral history—recorded over fifteen hours in seven different interview sessions—produced a 423-page transcript with appendices that feature family photographs and historic documents from Bell’s career.

Along with thorough coverage of his scientific research, Bell shared fascinating stories about his family’s Russian ancestry, including both his parent’s separately fleeing the Soviet Revolution to ultimately meet and settle in New York City, as well as discussions on writing shared with Bell’s uncle, the Russian-born French novelist Henri Troyat. Bell’s early interview sessions also recount his education at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in the early-to-mid-1960s, along with the historic evolution of chemical engineering as an academic discipline. In rich detail over several interview sessions, Bell discussed his collaborations and scientific research in four thematic areas: reaction engineering of plasma processes; heterogeneous catalysis research on new materials and energy resources; multi-technique catalysis studies in structure-property relations; and applications of theory to catalysis. Bell then shared his extensive administrative career at UC Berkeley, which included twice chairing his own department, serving as dean of the College of Chemistry, as well as chairing various committees in UC Berkeley’s Academic Senate. In his final interview session, Alex—as he is known to friends and colleagues—discussed his personal life as a father and a husband.

Alexis T. Bell was born on October 16, 1942 in New York City as the only child to immigrant parents who taught Bell to speak and read Russian fluently—a skill that, as noted below, later helped launch his now-storied career in catalysis. Bell grew up in midtown Manhattan and attended McBurney School, where Bell further fostered a burgeoning interest in science. He then studied chemical engineering at MIT, earning his bachelor’s degree in 1964 and his PhD in 1967. Just prior to completing his dissertation, on a chance visit to UC Berkeley during a cross-country road trip, Bell introduced himself to faculty in what was then simply called the Department of Chemical Engineering. Soon thereafter, in 1967, he accepted their offer to join the faculty where he has remained his entire career. In 1975, Bell became—and remains—a Principal Investigator in the Chemical Sciences Division at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. He has since been elected as a member of the National Academy of Engineering and the National Academy of Sciences in the United States. And his collaborations in catalysis with Russian (then Soviet) scientists starting in 1974 and with Chinese scientists beginning in 1982 eventually earned his selection by the Chinese Academy of Science as an Einstein Professor and his award as an Honorary Professor of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

An important through-line in Bell’s oral history is how it provides human context to the significant scientific contributions he has made, particularly Bell’s steady progress to produce an exquisitely detailed understanding of how complex chemical reactions occurring on the surface of heterogeneous catalysts proceed and are related to the composition and structure of that catalyst. Throughout his oral history, Bell discussed not only his technological innovations and experimental observations, but also his social networks of collaboration and the ways in which funding shaped both the content and processes of his knowledge production. For instance, Bell’s application in the early 1990s of experimental methods in combination with theoretical methods is now used by virtually all practitioners of catalysis science today; and here, Bell discusses with whom and how that work evolved. Additionally, Bell explains how various funding streams—like public research monies from the U.S. Department of Energy versus corporate research funding from BP (British Petroleum)—differently catalyzed the kinds of questions he could ask and the ways he could pursue scientific answers. As Bell explained, “I’ve learned—and I’m sure many other people who have done science and engineering have learned—that scientific activities don’t tell you what questions to ask. They give you answers, or partial answers, but the questions to ask are part of the human process.” Similarly, Bell’s discussion of his career in University administration while maintaining an active research program outlines how internal and external dynamics, as well as human and non-human forces, all shape the academic work and social evolution of UC Berkeley itself.

At Berkeley, Bell has now dedicated over half a century to developing the discipline of chemical engineering, especially the field of catalysis, often in pursuit of increased sustainability. When asked about remaining at UC Berkeley throughout his career, Bell replied: “There has never been a place that was so attractive to me that I wanted to leave Berkeley. I’ve told many people that, you know, Berkeley is not perfect, by far. … But what remains constant are the people—the quality of the people. And that’s what brought me out here to begin with; that’s what’s kept me here; and that’s what will keep me here. I really feel very privileged to be a part of the faculty here. I tell everybody that being a full professor at Berkeley is the best you can do in the academic world. And the kinds of students we attract, the kinds of visitors we have, the fact that you’re, so to speak, at the belly button of the world—everybody wants to come to Berkeley and visit and see you and talk to you. You’re constantly engaged intellectually.”

In his oral history, Bell also shared the interesting story of how and why he first began catalysis research in the early 1970s—a story that further reveals the “human process” and the social contexts of his science. Today, Bell is a world-renowned expert in heterogeneous catalysis. But when he first joined Berkeley’s faculty in 1967, his initial research focused on plasma chemistry, not catalysis. As a new faculty specialist in plasma chemistry, Bell received mentorship from elder chemical engineering faculty like Charles Tobias and Gene Petersen. In the early 1970s, Petersen approached Bell with an opportunity to use some additional research funding left over from an early Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) grant. The only catch with the funding was the research must be done on catalysis. Not wanting to turn down money for research, Bell recalled asking, “‘What do I know about catalysis?’ Well, virtually nothing. Never worked in the area. But I had, as a graduate student, done these translations of papers from Russian to English for Bill Koch.”

Earlier, in the mid-1960s, Bell and William Koch (the brother of those other well-known Koch brothers) were both graduate students in chemical engineering at MIT. William Koch asked Bell to translate from Russian a few Ukrainian Chemistry Journal articles on catalysis. Bell did so as a favor, and Koch went to work on re-creating those Ukrainian experiments. But as Bell recalled, Koch “could never get the reactors to stop from blowing up, because he would use explosive mixtures.” Nearly a decade later, Bell dug up copies of his translations and decided to build upon them for his first foray into catalysis research. With the remaining EPA funding from Gene Petersen’s grant, Bell purchased a new infrared spectrometer and promptly began creative in-situ catalytic research with a graduate student named Ed Force. According the Bell, Force “had been an undergraduate here at Berkeley, left to work for Chevron several years, and then came back, which is unusual for one of our undergraduates to come back. He was, in fact, older than I was.” Together, Bell and his elder grad-student Force completed new research on ethylene epoxidation, which they then published in 1975 in the prominent Journal of Catalysis.

In the mid-1970s, Bell and Force’s catalysis research garnered attention from established leaders in the field. Gábor Somorjai, a specialist in surface science and catalysis in Berkeley’s Department of Chemistry, read Bell’s publications and soon initiated a cross-departmental collaboration with Bell that lasted many fruitful years. Bell’s initial catalysis publications also caught the eye of Wolfgang Sachtler, an internationally prominent chemical engineer who then headed catalysis research for Shell Oil Corporation in Amsterdam. Bell remembered how, in his own incipient catalysis research, “We were able to show that you could get selectivities above the theoretical one predicted by Wolfgang Sachtler.” So, when Sachtler came to Berkeley to visit Gábor Somorjai, Sachtler insisted on meeting Bell. Their meeting highlighted some of Bell’s core attributes: he remains a consummate professional, calmly confident and in full command of his intellectual abilities and achievements, even under pressure.

As Bell remembered it, “Wolfgang came to my office and started immediately challenging me on my interpretation of the data, and that you could get to these high selectivities.” For over an hour before lunch and throughout an awkward meal with other Berkeley colleagues, Sachtler interrogated Bell. “It was unnerving to be challenged,” Bell explained, “but I felt that I understood what we had done well enough that I wasn’t going to just cave in to authority. Why should I do that? So, I stood my ground, in a professional way, which didn’t please him.” Soon thereafter, Bell received and accepted an invitation to visit Sachtler’s lab in Amsterdam where, again, he received further cross-examination by Sachtler and, this time, several Shell Oil researchers. “I got a grilling in their home office, and again stood my ground,” Bell recalled. History proved Bell correct: subsequent research at Union Carbide showed the selectivity could increase from 67 percent—then considered the theoretical limit—to beyond 90 percent. So, what lesson did Bell take from his initial foray into catalysis research and these interrogations from Sachtler? Bell shared, “I took from it that if I’m going to stick my neck out, I’m going to get it whacked. But I have a thick neck.”

From his own telling, Bell’s now-celebrated career in catalysis began with an amalgam of interpersonal connections, generosity from fellow faculty, achievement with an excellent student, and influential publications that signaled new opportunities for the field. Stories like this throughout Bell’s oral history offer insight not only into the material and observable realms of science, but the social and “human process” of science as well.

It is with great pleasure that we now publish Alexis T. Bell’s extensive oral history. Many thanks to the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering—particularly current department chair Jeffery A. Reimer and former department chair and prior Provost and Senior Vice-President of the UC system Jud King—for their vision and generosity in securing funding for this important interview with their colleague. And special thanks to Alex Bell for his dedication to this project and for sharing wonderful memories of his life and his career at UC Berkeley.

You can read Alex’s interview here:

— Roger Eardley-Pryor, Ph.D.

Intersectional Progress through Women in the Sierra Club

By Ella Griffith, UC Berkeley Class of 2020

In the Spring of 2019, I began work in the Undergraduate Research Apprenticeship Program (URAP) under Dr. Roger Eardley-Pryor at the Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library. Initially, I was interested in narratives around environmental justice and how this theme was, or was not, explored in the Oral History Center’s large archive of interviews with Sierra Club members, several of which were recorded over a half-century ago. The Sierra Club, one of the largest and oldest environmental advocacy organizations in the United States, has historically struggled with issues of environmental justice and inclusivity, and it recently publicized its reckoning with those legacies. My own reading through interviews in the Sierra Club Oral History Project made it clear that often, the female members within the Club have been the drivers of change on these issues. At the end of my first semester of work, the nuanced roles and perspectives of women in the Sierra Club emerged as the captivating focus in my URAP research.

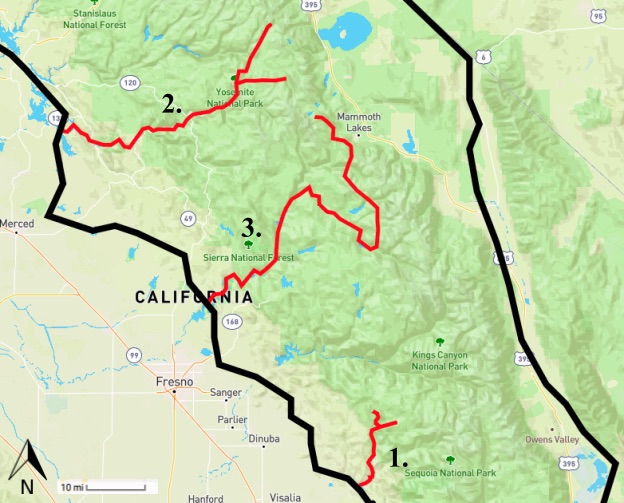

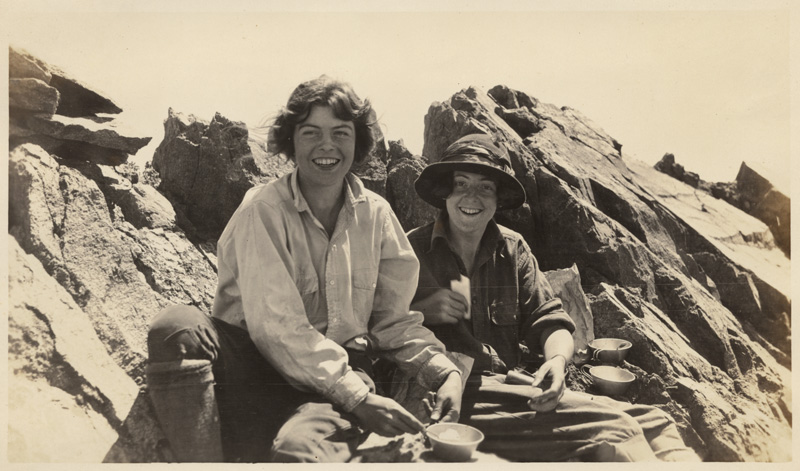

Over the past year, as I continued to read through these interviews of women in the Sierra Club, I pulled out selected quotations and analyzed their content. The capstone of my work is “Sierra Club Women: An Annotated Bibliography of Women’s Oral Histories in the Sierra Club Oral History Project.” This annotated bibliography of Sierra Club interviews with women includes archival photographs and a 2D map that I created by tracing the backcountry hiking routes that several Sierra Club women took on some of the Club’s early High Trips. The thirty interviews I annotated reflect and unpack a variety of common themes that these women grappled with related to their work within, and adjacent to, the Sierra Club and the greater environmental movement. The core themes I identified in these women’s interviews include “Outdoor empowerment”; “Pioneering activism”; “Intersectionality”; “Women as nurturers and cult of domesticity”; “Leadership labor and gender”; “Proximity to male club members”; “Legislative process”; “Early Sierra Club High Trips”; and “Environmental elitism.”

As a woman and environmentalist, reading stories about triumphs and obstacles for these female environmentalists of the past was both exciting and emotional. I gained a better perspective on how far the intersectional environmental movement has come and what aspects of environmental inclusivity I took for granted, thanks to the work of generations before me. At the same time, I felt these themes reflected much of my own life in the present.

By far, however, the most relevant and consistent theme that I saw reflected in my own life is “Environmental Elitism.” Oftentimes, the women interviewed came from very similar affluent backgrounds. They were encouraged to explore the outdoors as kids, and they had the time and resources to do so. Those that did hold leadership positions were volunteers; they did not have to worry about missing supplemental income to support themselves or their families. And every single one of the women interviewed in the Sierra Club Oral History Project were white.

When I started this research, I knew there were narratives and analysis missing from the mainstream history of environmentalism. The annotated bibliography of women in the Sierra Club that I created highlights some of those missing voices. I am glad this resource now exists, and I hope people use it in the future. But there are still many voices missing from our regular education and from our understanding of history. Black and brown scholars, activists, and environmentalists have long been excluded from the narrative of environmental history and denied credit for their contributions. I challenge readers to focus on narratives they have not yet explored within the Oral History Center’s archival collection. Have you had the chance to read through the African American Faculty and Senior Staff project? If so, revisit the important OHC director’s column from February 2020 outlining other important Black oral histories in their collection. In particular, Carl Anthony and Henry Clark and Ahmadia Thomas are among the few oral histories that explicitly focus on toxins and environmental justice. Additionally, have most of the oral histories you have read been narrated by men? My annotated bibliography on Sierra Club Women is just one slim piece of a broader collection of female interviews. For instance, Oral Histories of Berkeley Women highlights some of the oldest oral histories in the collection conducted with women who have been a part of UC Berkeley’s institution since they were granted admittance 150 years ago.

Through my URAP experience, I have learned that oral histories provide us a unique and raw insight into the perspective of the past. Our task, as historians, is to illuminate and analyze all of these voices, especially those that have been left out for so long. But do not forget about uplifting the voices of the present. Who are we not listening to this very moment? Who is making history as we speak? And what will you do to ensure they are not left out in the future?

** A vast collection of papers, books, videos, and toolkits exists on the subjects of environmental racism and justice. Here are some of the resources that helped me learn about environmental justice: Dr. Carolyn Finney, now a professor of Geography at the University of Kentucky, and a former professor at UC Berkeley who was denied tenure, wrote the book Black Spaces, White Faces: Reimagining the Relationship of African Americans to the Great Outdoors, which examines why Black people are so underrepresented in nature, outdoor recreation, and environmentalism. Another one of my Cal courses introduced me to the report “Toxic Wastes and Race at Twenty, 1987-2007,” about grassroots struggles to dismantle environmental racism in the United States. This report from 2007 revisits the foundational “Toxic Wastes and Race in the United States” study produced by the United Church of Christ’s Commission on Racial Justice in 1987, and it further examines how hazardous waste facilities exist disproportionately in close proximity to BIPOC communities, while also highlighting the lack of progress in addressing this issue since the first report, now over three decades old. Finally, the EPA created EJSCREEN: Environmental Justice Screening and Mapping Tool, which combines environmental and demographic data to visualize the intersection of environmental and public health.

—Ella Griffith, UC Berkeley Class of 2020

Ella Griffith graduated in May 2020 from UC Berkeley with a Bachelor of Science in Conservation and Resource Studies. From the Spring 2019 semester through Spring 2020, Ella conducted research in the Oral History Center and earned academic credits as part of UC Berkeley’s Undergraduate Research Apprentice Program (URAP). URAP provides opportunities for undergraduates to work closely with Berkeley scholars on the cutting edge research projects for which Berkeley is world-renowned.

Expertise as a Social Endeavor: Learning from Oral History

Our narrators at the Oral History Center are often experts in their chosen fields of engagement—perhaps as a preeminent scientist, a pioneering lawyer, an acclaimed author, or an outstanding executive. These accomplished narrators cultivated their particular expertise throughout their lives, often in dedication to creating new knowledge or perhaps by revealing new ways of orchestrating and operating in the world. In American culture, we’re often encouraged to imagine these experts as singular actors, lone wolves who separated themselves from the pack to achieve their individual successes. Occasionally, that’s true. For some narrators, we could be forgiven for considering their advanced scientific knowledge or their expertise in jurisprudence as singular, sovereign, sui generis, and almost abstract. And perhaps the standard oral history interview format — with its focus on an individual recounting their particular experience — lends itself to seeing these experts as independent actors, perhaps even separate from society. However, in my experience this past year, my oral history interviews with experts have emphasized how human connections and deeply personal interactions provided the firm bedrock for these experts’ intellectual advancements and accomplishments.

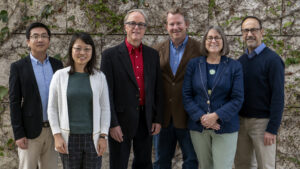

Throughout 2019 and into the start of 2020, I had the honor of completing in-depth oral history interviews with several highly accomplished experts. These experts included the following people in order of when we completed their final interview session: Michael R. Peevey, an entrepreneur and former president of the California Public Utilities Commission; Alexis T. Bell, an internationally renowned scientist in UC Berkeley’s Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering; Michael R. Schilling, an analytical chemist and head of Materials Characterization at the Getty Conservation Institute in Los Angeles; Robert Praetzel, a lawyer and conservationist whose legal battles helped preserve the Marin Headlands that are now part of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area; Nancy Donnelly Praetzel, a graduate of UC Berkeley in 1953 who worked in the early years of the commercial airline industry; Samuel Barondes, a medically trained scientist who helped pioneer the field of biological psychiatry; H. Anthony Ruckel, a pioneer of environmental law who later served as president of the Sierra Club; Lawrence D. Downing, a lawyer and environmentalist who also became president of the Sierra Club; and John Briscoe, an internationally recognized trial lawyer with numerous cases before the US Supreme Court, as well as a published poet, historian, and restauranteur. Throughout 2019 and into 2020, my time with these experts occurred across forty-five separate interview sessions that recorded over 110 hours of oral history.

When I met these experts to conduct their oral histories, I frequently had two sets of realizations.First, absolutely, this individual is an expert and many of their accomplishments are exceptional. Yet, I also realized that their expertise was rarely something they framed as an individual accomplishment. The classic lone-wolf narrative of success simply did not align with the stories they shared about themselves. When these experts and I spoke by phone, when we planned together how to record their life narrative, when we sat face-to-face during recorded interview sessions, and when I listened closely to their stories, instead of hearing tales of purely individual achievement, I heard them share various ways their expertise was cultivated socially with the profound support or influence of others—dear friends, mentors, teachers, rivals, loved ones. Yes, these experts are all individuals with unique stories and perspectives to share; and at the same time, the cultivation of their expertise and their experiences as experts are extremely social, interpersonal, and sometimes intimate.

In commemoration of conducting their oral history interviews this past year, here are a few ways in which these narrators described the development of their expertise and successes as socially constructed endeavors:

Samuel Barondes formed life-long friendships with outstanding researchers and future Nobel-laureates at the National Institutes of Health. In his oral history, Barondes explained how his personal relationships helped launch his research career, where he applied the techniques of molecular biology to help establish the new field of biological psychiatry, which conceptualized mental illnesses as physical brain disorders requiring a multilevel approach ranging from genetic to psychosocial mechanisms.

Alexis T. Bell became an internationally recognized expert on heterogeneous catalysis, yet his initial research focused on plasma chemistry, not catalysis. Bell explained how, in the early 1970s, support from Gene Petersen, an older faculty member in chemical engineering, as well as collaborations with a graduate student named Ed Force, both played key roles in helping launch Bell’s now-storied career in catalysis research.

John Briscoe has argued legal cases before the California Supreme Court, the United States Supreme Court, and the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague. Briscoe credits numerous mentors that became dear friends who helped advance his career, including legal legends like Philip C. Jessup, Stefan A. Reisenfeld, and perhaps most importantly Louis F. Claiborne. Briscoe and Clairborne met as rivals arguing on opposing sides in the US Supreme Court before developing a deep friendship in which they later became law partners as well as godparents to each other’s children.

Lawrence D. Downing’s leadership in the Sierra Club included working with his best friend and fellow Club officer Denny Shaffer to help establish leadership opportunities for other volunteers, as with their advocacy of the Club’s Grassroots Effectiveness Program in the 1980s. Downing also formed international friendships with founders of the John Muir Trust in Scotland, and together they protected Scottish wildlands while promoting the preservationist legacy of Sierra Club founder John Muir, who was born in Scotland.

Michael R. Peevey forged strong social connections and collaborations throughout his career in labor economics, in government relations, in growing California’s energy industry, and while regulating it. As president of the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC), Peevey teamed with Republican and Democratic governors as well as members of the “Energy Principles Group”—made up of the CPUC, the California Energy Commision, the California Independent System Operator, and the California Air Resources Board chaired by Peevey’s friend Mary Nichols—to help make California a world leader in confronting climate change.

Nancy Donnelly Praetzel has deep family roots in the Bay Area that extend at least to 1893 when her grandfather, Ernest Clayton, arrived from England. In the late 1930s through early 1950s, Nancy Praetzel and her sister Genie hiked through Marin County with their grandfather, who would then paint pictures of flowers that the girls collected. In 2013, a family collaboration between Nancy, Genie, and Nancy’s daughter Annie rediscovered and promoted Ernest Clayton’s wildflower paintings so that others could enjoy these family heirlooms depicting California’s fragile beauty.

Robert Praetzel’s legal career ran the gambit from estate planning to defending protestors against logging old growth redwoods to winning the case that finally stopped the Marincello development project in Marin County. Praetzel credits his early legal training to exceptional professors in the “Sixty Five Club” at UC Hastings College of Law but most especially to Wallace “Wally” Myers, an experienced lawyer in Marin County who guided Praetzel how to build a successful and eclectic career.

Tony Ruckel won his first major environmental case in 1969, establishing an important legal precedent that ultimately enabled the designation and preservation of vast wilderness tracts across the United States. Ruckel recalled, “There wasn’t any guidance. There weren’t any directions. We couldn’t go to a casebook, or open a volume and say, ‘Hey, this is authority for what we’re trying to do.’” As a result, Ruckel and other Sierra Club pioneers of environmental law relied on each other to develop and expand their expertise.

Michael Schilling applies his chemical-analysis expertise to extensive collaborations with art curators and art conservators around the world. Understanding the surface chemistry of art materials, as well as how and why the artist created their art, are essential for devising safe and ethical treatments to conserve or restore art. “You need all of that knowledge,” Schilling explained, “to really tell the entire story of an object or an artifact,” and combining that knowledge requires teamwork.

All the expert oral history narrators I recorded this past year repeatedly emphasized the importance of their interpersonal relationships and collaborations in their own accomplishments. Their own stories about creating new knowledge and achieving great successes reiterate how knowledge, as well as material things, are the product of historical events, social forces, and ideologies. These narrator’s stories encourage us to understand the construction and application of expertise as a deeply social endeavor. Thank you to all the narrators listed above—as well as those from years past and those we’ll interview in the future—for sharing their expertise and for collaborating with all of us at the Oral History Center.

— Roger Eardley-Pryor, PhD