Author: Amanda Tewes

Kathleen Dardes and the Global Impact of the Getty Conservation Institute

The Getty Oral History Project includes interviews with individuals across the spectrum of the Getty Trust, including the Getty Conservation Institute (GCI), which does international work to advance the field of art conservation. Of the four programs in the Getty Trust, the GCI stands out both for its scientific collaboration with other Getty entities, and its dedication to sharing conservation information worldwide. Kathleen Dardes’ lengthy career working in various GCI training programs is emblematic of this mission.

Kathleen Dardes is the head of Collections at the Getty Conservation Institute. She studied art history and classics at Temple University in the 1970s, and then went on to study art conservation at the Courtauld Institute of Art in the 1980s, specializing in textile conservation. Dardes then worked as a conservator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine, and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. She joined the GCI in 1988 as the senior coordinator for the Training Program.

When Dardes joined the GCI in 1988, this Getty program was only three years old and trying to establish itself in the field. Dardes recalls working to build credibility as an international art conservation organization, and struggling against “skepticism” about this new Getty entity:

“I think part of it had to do with the fact that we were so darn rich, and we could buy pretty much anything we wanted and could do anything we wanted, and we weren’t beholden to anyone except our trustees. That gave us a certain freedom, which I think was sometimes resented in the broader field. So we had to prove ourselves.”

Part of the way the GCI proved itself was investing heavily in the international training programs Dardes helped create to share conservation best practices worldwide. These included the idea of preventive conservation, or delaying the deterioration of objects through procedures like managing collections environments. Dardes explained the need for this training, saying,

“In the field, you’d hear these funny stories about people making all sorts of elaborate measures to control environments in a gallery space or storage area, but the roof was leaking [laughs] or there was a pest issue or something. So we were looking at the small details, and not the larger system that the museum is.”

In recent years, the GCI has undertaken a project called MEPPI or Middle East Photograph Preservation Initiative. Dardes explained that the GCI and several partners worked hard to establish much-needed photograph preservation courses throughout the Middle East to help institutions protect these collections. This project included many challenges, not the least of which is political instability. In her interview Dardes shared the inspirational story of one MEPPI participant’s dedication to conservation, even in the midst of the Syrian Civil War:

“When we arranged a follow-up course in Lebanon, which was open to people from throughout the region, one of the participants in Syria, at great personal risk, got on a bus with her father, who was there to protect her, and took a bus from Syria to Beirut. Took her two days to do that, a trip that normally takes half a day. Couldn’t fly because it was too difficult to go to the airport, too risky, but came to Beirut to be with her old colleagues and take a course—which we all found absolutely stunning. But that’s how committed she was, not only to the course itself, to the collections she was in charge of, but also to the network that was forming. She wanted to see her old colleagues and be involved in this thing called MEPPI. So it sounds very pollyannaish, but it was a wonderful thing. People who don’t often have the opportunity to be involved in projects like this don’t take them for granted. It was something that we all thought was remarkable.”

Though she has not explicitly used her skills as a textile conservator while at the GCI, Dardes has found opportunities to engage with the larger implications of cultural heritage around the world. Indeed, being a part of the Getty Trust has opened global opportunities for her—and the GCI—to share and teach conservation best practices on an incredible scale.

To learn more about her work with the Getty Conservation Institute, check out Kathleen Dardes’ oral history!

From the Archives: Irvin Shiosee

By Miranda Jiang

Miranda Jiang is an Undergraduate Research Apprentice at the Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley. She is a UC Berkeley history major graduating in Spring 2022.

“I just can’t go out there with my Indian costume, because when I do that they might think, you know, oh, here comes a savage Indian.” — Irvin Shiosee

In 1942, Irvin Shiosee, a member of the Laguna Pueblo of the Southwest, moved with his family to Richmond’s boxcar village. Along with many members of the Acoma Pueblo, members of the Laguna Pueblo moved to this village (often referred to both as the Santa Fe Indian Village and the Richmond Indian Village) beginning in the 1920s. This migration followed a verbal agreement with the Santa Fe Railroad in California, which promised them employment in railroad maintenance and construction.

As part of the “Rosie the Riveter” project, the Oral History Center has conducted over 250 interviews with individuals who lived in the Bay Area during World War II, including people who lived in Richmond’s boxcar village. In his 2005 interview, Shiosee recalls his childhood there: he describes rows of around sixty boxcars placed along the railway, each housing one or more families. The children’s playground was a small “swamp” where they would take makeshift rafts and search for tadpoles. Among other anecdotes, Shiosee describes how his father built his family an oven to make sure they didn’t “lose any of [their] traditional food,” such as sweet “Indian pudding” made in the oven overnight.

Shiosee’s life within the village often seemed like a separate world from life outside and public school. Whereas day school at his old reservation was with other members of his tribe, at Peres Elementary School, there were Richmond-area children of many ethnicities. He had to learn English through Dick and Jane, and indigenous students were only allowed to speak English. He describes how students would “squeal on [them]” if they heard Shiosee or other Pueblo kids speaking Keresan. Subsequent punishments included standing against the wall or completing chores such as wood-chopping and cleaning the bathroom.

Shiosee also encountered stereotypical perceptions of indigenous people through his interactions with other children. On the first day of school, the teacher couldn’t pronounce his last name while introducing him to the class. He could see the surprise on his classmates’ faces upon hearing that he was an “American Indian boy.” The media only represented people like him in stories of “cowboys versus Indians,” so to these American children, indigenous people were the enemy.

“So that’s how they saw me,” he says, “as a savage Indian, I guess.”

Neither did the administration show much support. Children viewed him as a figure from fables and histories, and they would come up to pat him. When he whacked their hands away, teachers would send Shiosee to the principal’s office where he would be disciplined for fighting.

As Shiosee grew older, he became more and more aware of two separate realms. In his life outside the village, he knew he would face hostility if he showed his Pueblo identity. He describes walking to junior high school in the morning:

“I had to take off my Indian costume and hang it on this fence that I had to go through, and then put on my street clothes… ”

Yet despite going to school in an English-speaking environment and being pressured to assimilate, Shiosee remained closely connected with his culture and language. At the end of the interview, Shiosee describes his relationship with English and Keresan:

“English language to me is like I’m copying somebody. It’s not my natural language. The language that I speak comes from my heart on to you, you know. But to imitate somebody is not really from the heart. It’s coming from the mouth.”

In 1982, the Santa Fe Railroad shut off the power to the village. Although Richmond’s boxcar village was populated for around 60 years, it is now a relatively little known piece of Bay Area history. It has been documented in a number of writings, including essays by emeritus Oregon State University professor Kurt Peters (see “Boxcar Babies: The Santa Fe Railroad Village at Richmond, California, 1940-1945”). An event at Richmond’s Native Wellness Center in 2009 included three former inhabitants of the village as speakers, two of whom have interviews with the Oral History Center.

The boxcar village no longer exists physically, nor does it seem present in the Bay Area’s public consciousness. Although the inhabitants of the village attended local schools and events, and were spatially near other Bay Area neighborhoods, the Pueblo people preserved their culture and ways of life within the Richmond boxcar village. Ensuring knowledge of the Pueblo’s long history in the Bay Area is an important step towards recognizing what Shiosee already states in his interview: that rather than being faraway relics of history, he and his people are part of the present.

As a first step to learning more about the lives of Laguna and Acoma Pueblo people at this remarkable settlement, I encourage you to view the Rosie project’s compilation of interview segments related to the village. I further recommend reading and watching the full interviews, such as Irvin Shiosee’s interview.

2019 Oral History Association Conference Review

This year’s annual meeting of the Oral History Association (OHA) was hosted in Salt Lake City, Utah, where we caught just a glimpse of the region’s famed winter season, but were kept warm by invigorating discussion of oral history best practices and challenges.

This year’s annual meeting of the Oral History Association (OHA) was hosted in Salt Lake City, Utah, where we caught just a glimpse of the region’s famed winter season, but were kept warm by invigorating discussion of oral history best practices and challenges.

At the OHA conference I was especially impressed by the number of panels on doing oral history with indigenous people. In the roundtable session “Native American Stories of Peoplehood,” panelists grappled with how they incorporated oral tradition from their indigenous communities into oral history. It left me with a good reminder: narrators’ histories do not necessarily begin at birth, and their ancestors may play a large role in how they frame their own lives. One audience question from this session also asked when and how to include proprietary information about tribes in oral histories (i.e.: sacred stories, songs, ceremonies). One panelist remarked that this complicated area is something to review with both narrators and tribal elders. And yet, even when not interviewing in indigenous communities, it is important to discuss parameters for interviews long before pressing record!

Another highlight was the keynote speaker Isabel Wilkerson. The session was standing room only as Wilkerson spoke about her 2010 book, The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration. Wilkerson walked the audience through her process of finding and interviewing individuals whose life experiences humanized the stories of the twentieth-century Great Migration of African Americans from the South to the North, Midwest, and West. I groaned in sympathy as she recalled difficulties in finding narrators. But most importantly, I was drawn to Wilkerson’s understanding that oral histories are precious and time-sensitive products that often need to be prioritized over extensive archival research. I, too, have lost narrators before being able to interview them, and I have often wondered what stories they could have told to change the historical record as we know it. In short, Wilkerson validated the work of oral history, and reminded us that the most important work oral historians do is to help others tell their stories, especially when they change how we view the past.

After attending sessions on making oral history a sustainable career, I walked away from this year’s meeting with an even greater sense of the importance of building a community of oral historians beyond the academy and formalized training programs. Often it is the practitioners on the ground who best connect to under acknowledged individuals with important stories to share. So, as an interviewer with a seat of privilege, my questions to other practitioners are: how do we support oral historians working in the field? How do we further democratize oral history? I look forward to continuing these discussions next year in Baltimore!

Women of SLATE: Susan Griffin and Julianne Morris

The Oral History Center has been conducting a series of interviews about SLATE, a student political party at UC Berkeley from 1958 to 1966 – which means SLATE pre-dates even the Free Speech Movement. The newest additions to this project include two women who joined SLATE in the early 1960s at a tumultuous time at UC Berkeley: Susan Griffin and Julianne Morris.

Susan Griffin is an accomplished writer, and was a member of the UC Berkeley student political organization SLATE in the early 1960s. Griffin grew up in Los Angeles, California. She attended UC Berkeley, where she became active in SLATE, attending protests and engaging in political discussions. Griffin left Berkeley in 1963, but continued to work as a writer in the San Francisco Bay Area, producing many works, including Woman and Nature: The Roaring Inside Her. Over the years, Griffin remained active in causes of social justice, including the women’s movement and anti war protests.

Julianne Morris is a former social worker and mediator, and was a member of the UC Berkeley student political organization SLATE in the early 1960s. Morris grew up in Compton, California, and attended UC Los Angeles, where she helped found the student political group PLATFORM based on discussions with SLATE members. She then transferred to UC Berkeley, where she became active in SLATE, attending protests and running for ASUC student representative. Morris stayed at UC Berkeley to earn her master’s in social work. She then moved to New York City in 1964 and was a social worker for many years, where she helped start women’s centers, rape crisis programs, and became a part of the women’s movement. She returned to Berkeley in the early nineties and reconnected with former SLATE friends through reunions and an ongoing political discussion group.

Griffin and Morris were among the second generation of SLATE activists and joined the group around the same time in 1960 – after the famous HUAC protest in May of 1960 and before the Free Speech Movement in 1964. They also have similar upbringings in Jewish (adoptive family, in Griffin’s case) and politically left families who feared encroaching McCarthyism. These backgrounds helped ignite a political consciousness in both women that led them to SLATE.

Griffin and Morris’s oral histories build on an archive of SLATE history, but they also speak specifically to their experiences as women in this group. Both recount instances of feeling marginalized as women, of being left to do the “scut work” like mimeographing and cooking for hungry activists. They even recount tensions at a 1984 SLATE reunion in which those newly empowered by feminism expressed displeasure with the way they had been treated; many of the men denied this discrimination, but others took it to heart and sincerely apologized. And yet, Griffin and Morris both were encouraged to run for ASUC office in the early 1960s, campaigning on the SLATE platform and often pushing their own boundaries of what they thought was possible. Despite the challenges of being a woman in this campus political group, there were still opportunities to grow as individuals and as leaders.

Listen as Susan Griffin and Julianne Morris share their memories of running for ASUC on the SLATE ticket at UC Berkeley:

Even though both Griffin and Morris had decreased participation in SLATE or left campus by 1964, their experiences in the organization clearly shaped their perspectives about politics and activism, particularly as they both became involved with the women’s movement. Griffin explained, “The guys may not have known it, but they were training feminist activists in all that period.”

Most importantly, by recalling their times with SLATE and later political work, both Griffin and Morris emphasized the importance of building and sustaining community in activist groups. For Morris, joining SLATE helped her find a place where she belonged. Griffin pointed to organizations of politically like-minded individuals as ways to create belonging and “joy” through an almost spiritual experience of protest.

Listen as Julianne Morris reflects on SLATE’s impact on the Free Speech Movement:

Come learn more about SLATE, and explore the oral histories of Susan Griffin and Julianne Morris!

Bay Area Women in Politics Oral History Project

This project is unique in that it focuses on women in one geographic region in order to get a clearer picture of the breadth of political work women have been doing on the ground and behind the scenes.

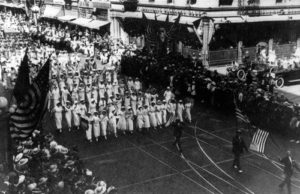

Nineteen ninety-two has been dubbed “The Year of the Woman,” a phenomenon in which a wave of women candidates swept local and national races for public office. California led this charge by becoming the first state in American history to be represented by two women senators—Barbara Boxer and Dianne Feinstein. And since 2016—after a presidential election that provoked heated debate about gender discrimination and sexual harassment—many women stepped up to the challenge of engaging even more visibly in the American political system. Since then, organizations like Emily’s List and She Should Run reported record-breaking numbers of women who wanted to make their voices heard by running for public office.

And yet, 1992 was not the beginning of women’s political activism, but rather the culmination of decades of organization encouraging women to get involved and run for office. For generations, Bay Area women have built the foundations of political activism that span neighborhood organizations to support networks. And their stories inform our present.

In order to document these stories, I am developing the Bay Area Women in Politics Oral History Project to record the history of these local women and their impact on and journeys through politics. The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley continues to preserve stories about California politicians, but this project is unique in that it focuses on women in one geographic region in order to get a clearer picture of the breadth of political work women have been doing on the ground and behind the scenes. Documenting political engagement outside of traditional political venues will capture more stories about women in politics and a more diverse array of stories.

For instance, the pilot interview for this oral history project is with Mary Hughes, a Bay Area political consultant. In her interview, Hughes explained that “in politics and in political consulting, you either win races or you don’t. If you don’t win, no one hires you. If you do win, everybody wants to hire you.” Hughes’s successful career in the Bay Area spans decades and highlights the prominence of women in national politics. And though she does not wish to run for office herself, Hughes sees her role as someone who can best serve her community by managing the election process for political candidates—especially other women. Hughes’s recollections are an example of the kinds of stories that will drive this oral history project.

These long-form oral history interviews survey Bay Area political women’s backgrounds in and passion for political work through self-reflection. This format allows for comparisons between various avenues of political activism—like organizers and elected officials. It also reveals the importance of networks and mentors, and the impact they have had on women in the Bay Area political scene.

As engaged citizens, we need to know more about these women who helped create a space for themselves in Bay Area political life. Who are these women and what are their stories? From neighborhood organizations to national campaigns, what is the range of political activism in which these women engage? How has being a woman been a challenge or an asset to their political involvement? How have these women been working in the background of political life for generations? How does living and working in California affect political opportunities? What kind of political power do these women wield locally and nationally?

As we approach the hundredth anniversary of women’s suffrage, conducting oral histories with women activists and politicians in California’s San Francisco Bay Area will help shape the national narrative about women’s historic, current, and future roles in American political life. Further, gathering firsthand stories will help inspire and instruct a new generation of politically engaged women.

In addition to collecting primary source materials, The Oral History Center shares its collection with the general public through interpretive materials—like podcasts—and educational initiatives. Recording the contributions of these impressive Bay Area women—political fundraisers, organizers, and elected officials—through life history interviews is the first step in developing curriculum for workshops that cultivate young women’s political leadership. These workshops will use oral histories as a tool to foster civic engagement across the political spectrum, as well as to help develop confidence and skills of future women leaders. We also plan to create a podcast, a series of public forums, and a museum exhibit featuring these interviews.

We are currently raising funds for this project, and need your help to undertake the expansion of this ambitious oral history collection. You can support this project by giving to the Oral History Center. Please note under special instructions: “For the Bay Area Women in Politics Oral History Project.” To learn more about this project, please contact Amanda Tewes at atewes@berkeley.edu or 510-666-3687.

Amanda Tewes is an interviewer with The Oral History Center and specializes in California history and political culture.

The Oral History Center is a research program of the University of California, Berkeley. The OHC helps preserve contemporary history by conducting carefully researched video recorded and transcribed interviews. As part of UC Berkeley’s commitment to open access, archival copies of the audio/video and transcripts are placed in The Bancroft Library and are publicly accessible online.

The Science and Art of Oral History: My Internship Experience

Eleanor Naiman is a rising senior at Swarthmore College majoring in History. This past summer, Eleanor worked with historian Amanda Tewes of the Oral History Center on the Bay Area Women in Politics Oral History Project. As an intern, Eleanor researched the contributions of women to Bay Area politics and assisted Tewes with her interviews. Here, Eleanor reflects on her internship experience in the Oral History Center.

Eleanor Naiman, 2019

There is a science to professional oral history. From start to finish, the interview process requires meticulous attention to detail and respect for technique, form, and skill. When an OHC historian sets off to conduct an interview, be it a conversation with a Bay Area political consultant or with a Connecticut anthropologist, she does so equipped with heavy black bags of tools and folders and parts that, to the untrained (read: intern) eye, might seem better suited for the high-tech activities of a secret agent than the practice of oral history. And yet, each cord, mic, form, and gadget plays an integral role in the interview process.

Over the course of my summer as an intern at the OHC, I’ve become better versed in this highly technical science of capturing a story. I’ve learned how to identify a potential narrator and with which forms to ask for her consent. I’ve spent long hours researching the entirety of her life, creating an outline of its twists and turns and of the people with whom it has come into contact. I’ve become a convert to the practice of the “pre-interview,” a conversation that allows the interviewer to check her facts and flesh out her timeline.

Even the intimidating black tool bags have become familiar. I’ve learned to unfold a tripod to just the right height. To angle a camera towards my narrator’s left cheek, framing her head from hair to collarbone and obscuring her lapel microphone. I know how to initialize an SD card; how to stop recording, then press power; and how to make the light in the room warmer or cooler based on the narrator’s proximity to a window. My technical skills are far from perfect, and it often takes me about five times longer to set up equipment than it should, but my fumbles and mistakes only reinforce my newfound appreciation for the complex science of oral history.

And yet, if oral history is a science, it is also an art.

I have learned that oral history, at its root, relies not on the positioning of the camera or the placement of the mic but on the strength of the trust carefully built by both historian and narrator during weeks of exchanges and phone calls preceding the interview itself. This trust is not quantifiable; a relationship, it turns out, is harder to assemble than a camera tripod.

I have learned how to speak my narrator’s language, repeating the terminology she’s used to reinforce her sense of ownership of her life stories. I know to follow the flow of her memories, asking open-ended questions that evoke the feelings she experienced in a time or place. I try to understand how my own biases inform my questions, and to consider how intersubjectivity influences the relationship my narrator and I can build. I have learned to listen more deeply than I ever have. Perhaps most importantly, I know to allow my narrator to guide our conversation as an equal partner in this history we’re creating together.

This summer I have become a techie and a philosopher, a stickler for spreadsheets and a careful listener, a more confident camerawoman and a historian never so acutely aware of all that she does not know. In short, I have become a scientist and an artist: an oral historian.

My First Brush with Oral History

I first encountered oral history in my master’s program in history at California State University, Fullerton. I chose the program because it had strong public history training, but in my research about the school I discovered the pedagogy included something called “oral history.” I scratched my head at that, but added that information to a laundry list of graduate school problems labeled: “I guess I’ll figure it out when I get there.” After all, I wanted training to be a museum curator – and nothing else.

Things didn’t go according to plan.

My introduction to oral history was immediate. In my first public history course, a fateful assignment meant I needed to lead a small group discussion about oral history as historical evidence and as practice. My sense of oral history at the time was pretty limited to oral tradition: elders informally sharing knowledge about the past. My group consisted of undergraduates and graduate students who also had little to no experience with oral history, so we set out to discuss: what is oral history and what is its value to public historians?

We debated the reliability of oral history, given its dependence on memory and subjective experiences. We talked about how differing approaches to transcription shade researchers’ experience with oral history source material. We also questioned whether oral history had a place in public history writ large, or if it should be a separate discipline. And yet, we all agreed that it was important to record people’s life experiences, that their stories are inherently valuable.

I began the assignment deeply skeptical of oral history, but at some point during this discussion I found myself defending the practice because of the value of these alternate stories. In part, public history springs from an activist tradition hoping to recover pasts not about white male leaders, but of the everyday and everyman. With that framework in mind, I ended up posing the question: is oral history the most egalitarian practice in public history?

My argument was that much of the time museum exhibits are the result of so-called experts communicating history to the public; it’s an expensive and laborious process that doesn’t always involve the people who witnessed the history presented in the exhibit. But oral history, it’s different. At its core, oral history involves two people sitting down to chat using potentially inexpensive equipment to record their conversation. This process takes place outside the Ivory Tower and requires talking – and really listening – to people in your community, people whose lives and expertise have often been under acknowledged or completely overlooked. In theory, oral history can invert the power structure of just who is the expert. Unlike the rest of the historical profession, oral historians don’t just study the past, they help shape documents about the past by interacting with the people who lived it.

It was during this initial assignment about oral history that I began to question where oral history fits with other historical evidence. I eventually concluded that oral history is different from other text-based sources because it comes with a set of complications about collecting the information. And yet, oral history is also different because sharing human experiences through oral tradition is a powerful tool in making sweeping historical narratives personal and relatable – this connection to the past is difficult to achieve through census records.

It was through these discussions and further exposure to the value of first-person interviews that I finally resolved my questions about how oral history relates to public history. And oral history has become an important mainstay in my toolkit in my career as a public historian.

“Sleeping with the Light On: Housing and Community at Berkeley” – The Berkeley Remix Podcast Season 4, Episode 1

“From early housing cooperatives during the Great Depression, to fights for racial and gender parity on campus, housing has been on the frontlines of the battle for student welfare throughout the University’s history.”

Bowles Hall opened in 1929 and housed about 200 students — all of them men.

This season of The Berkeley Remix we’re bringing to life stories about our home — UC Berkeley — from our collection of thousands of oral histories. Please join us for our fourth season, Let There Be Light: 150 Years at UC Berkeley, inspired by the University’s motto, Fiat Lux. Our episodes this season explore issues of identity — where we’ve been, who we are now, the powerful impact Berkeley’s identity as a public institution has had on student and academic life, and the intertwined history of campus and community.

The three-episode season explores how housing has been on the front lines of the battle for student welfare throughout the University’s history; how UC Berkeley created a culture of innovation that made game-changing technologies possible; and how political activism on campus was a motivator for the farm-to-table food scene in the city of Berkeley. All episodes include audio from interviews from the Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library.

“…realtors and others who owned apartment houses took the attitude that International House was to relieve them of the problem of racial housing. And I said, ‘On the contrary, International House was established to set the pattern for everyone to follow.’ ” — Rev. Allen C. Blaisdell

International House opened in Berkeley in 1930. It became not only a place where international students could live, but it was also co-oed — this defied social norms of the time.

Episode 1:

“Sleeping with the Light On: Housing and Community at Berkeley”

Written and produced by interviewer Amanda Tewes, UC Berkeley Oral History Center

We’ve come to think of communal living as a tradition for students, a rite of passage and a valuable lesson in community building. But for much of its history, UC Berkeley didn’t even have residence halls! Expanding and improving housing at Berkeley has been on the frontlines of the battle for student welfare throughout the University’s history. In this episode, we explore what home and community has meant to students at Cal, and how accessible spaces have supported social justice movements on and beyond campus.

In researching student life on UC Berkeley’s campus through our rich collection of oral histories, story after story about historical housing hardships jumped out at me. Everything from the price of room and board to discrimination impacted how Cal students interacted with the campus, and whether or not they were able stay and study at the University. However, these oral histories also revealed that students and administrators used housing to support social justice on their campus and in their community. To me, this resistance and resilience is the quintessential Berkeley story.

This episode includes audio from the Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library, including: Rev. Allen C. Blaisdell, Jackie Goldberg, Frank Inami, Marguerite Kulp Johnston, Edward V. Roberts, and Dorothy Walker. Voiceover of Ruth Norton Donnelly’s interview by Shanna Farrell. Audio from the “Which Campus?” video courtesy of The Bancroft Library. To learn more about these interviews or see all of the Oral History Center’s The Berkeley Remix podcasts, visit the Oral History Center.

Following is a written version of The Berkeley Remix Podcast Season 4, Episode 1: “Sleeping with the Light On: Housing and Community at Berkeley.”

Audio: (music)

Meeker: Hello and welcome to The Berkeley Remix, a podcast from the Oral History Center of the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley. I’m Martin Meeker, director of the Center. Founded in 1954, the Center records and preserves the history of California, the nation, and our interconnected world. This season, we’re bringing to life stories about our home — UC Berkeley — from our collection of thousands of oral histories. Please join us for our fourth season, inspired by the University’s motto, Let There Be Light: 150 Years at UC Berkeley. This is episode one, “Sleeping with the Light On: Housing and Community at Berkeley,” produced by Oral History Center’s Amanda Tewes.

Video: (music) Berkeley, oldest and largest of the University campuses…You can live in a variety of student residence facilities on this campus, but it’s more likely you’ll live off campus or travel back and forth each day. But many worlds are here within the complex world of a big, bustling campus.

Audio: (noises from moving day)

Narration: Like college campuses across America, moving day at UC Berkeley marks a pivotal moment in the lives of new Cal students. It’s the beginning of their college careers.

Audio: (noises from moving day) “Think how much you’re going to miss me.”

Narration: Parents say tearful goodbyes, students anxiously meet roommates. And moving into on-campus dorms symbolizes becoming part of the campus community, becoming a Golden Bear.

We’ve come to think of communal living as a tradition for students, a rite of passage and a valuable lesson in community building for young adults. Ruth Norton Donnelly, a student in the early 1920s, recalls her time at Cal.

Voiceover/Donnelly: …I think we learned more in living with each other than we could have learned in any other way…I learned to sleep with the light on, with the radio going, and with a card game going on in the room…I don’t know a better way to find out these things than to live with a group of people who care about you.

Narration: That’s actually Shanna Farrell reading from a transcript of an interview with Donnelly in 1966. The scene she describes is a familiar one. But it hasn’t always been the norm at Berkeley. For much of its history, the University didn’t even have dorms! It took Berkeley years to address campus housing, and this issue became an important platform for student activists.

Audio: (music)

Narration: From early housing cooperatives during the Great Depression, to fights for racial and gender parity on campus, housing has been on the frontlines of the battle for student welfare throughout the University’s history.

Audio: (music)

Narration: Despite a few experiments with campus housing, it wasn’t until 1929 that the school opened its first dormitory — Bowles Hall — which boarded about 200 students, all of them men. About a decade later, in 1942, Berkeley opened its first dormitory for women: Stern Hall, which accommodated just over 130 students. Both of these projects were funded through private donations — not the University budget.

But two dorms couldn’t house the entire student body, which was over thirty thousand. So students rented rooms at boarding houses, pledged into the Greek system, and joined co-ops.

Audio: (music)

Narration: During the Depression, a weak economy meant Cal students had to compete with locals for affordable housing. Many of them turned to co-operatives like the University Student Co-operative Association — or USCA. These were communally-owned units that the students ran themselves. Berkeley alum Marguerite Kulp Johnston lived in the co-op at Stebbins Hall.

Johnston: When I came to Berkeley in ’39, I had applied over a year before to the USCA, the co-op houses, because that was the only low-cost housing around. Everything was very expensive compared with it. Let’s see, they had about 600 students, I think, then in the co-op. There was one girls’ house of about a hundred, and about four or five men’s houses altogether. That was $24.50 a month, [for] three meals a day, seven days a week. I think then Bowles was running $60 a month, something like that, so it was less than half.

Narration: This made Johnston one of the lucky ones. She says housing conditions at the time were miserable. And students were largely on their own.

Johnston: When we were in school, the University’s stated position was: “We’re not concerned with where students live. We provide the education, and students provide their own housing.” This was a general policy.

Narration: Johnston was a member of the Student Welfare Council and the Associated Students’ Executive Committee. She pushed back against this policy.

Johnston: All of us who were interested in student welfare and student housing were screaming about this, saying, “Here you’ve got all these students living in hovels and living in basements. And people charging exorbitant rents for nothing but a pallet and a toilet down the hall that doesn’t flush,” and so forth, and promoted dormitories where kids could live healthfully.

Narration: But while administrators debated whether to build more university-controlled dorms, the problems with housing intensified. This was especially true for international students and students of color. Without guaranteed university housing, these students faced discrimination in their off-campus searches.

One solution to this discrimination was the expansion of the International House model that began in New York. The idea was to create a multicultural residence that would house international students and scholars, fostering intercultural connections. But when I-House opened in 1930 on Piedmont Avenue in Berkeley, it faced pushback from the local community. Rev. Allen C. Blaisdell was the first director of I-House. He recalls:

Blaisdell: …realtors and others who owned apartment houses took the attitude that International House was to relieve them of the problem of racial housing. I protested, in one case, to a realtor in regard to prejudicial matters and refusal to rent to national minorities and nationality groups. And his reply to me was, “Well, International House was built so that we would not have to be faced with this matter.” And I said, “On the contrary, International House was established to set the pattern for everyone to follow.”

Narration: Blaisdell wanted to show what inclusive housing could look like. I-House wasn’t just available to students of color; it was also co-ed. This policy defied social norms of the time and put I-House directly in conflict with the University.

Blaisdell: Well, the rules of the University were that any recognized housing unit at the University could not house men and women, so that International House was never on the approved housing list of the University in those days. The Dean of Women’s office co-operated in many ways, but they were basically opposed to this principle.

Narration: The Dean of Women’s Office opposed coed housing because Berkeley, like other college campuses, was responsible for protecting the “virtue” of women undergrads. So, to get around University regulations, I-House became what Blaisdell describes as “almost completely graduate student in nature.”

Blaisdell: But it was a problem at the beginning, largely because no man or woman could live in an approved boarding house, or rooming house, or residence hall, where men and women live under the same roof.

Narration: Stern Hall, that women-only residence the University built in 1942, was still the only dormitory for them to live on campus. Rosalie Meyer Stern funded the building, and insisted on its decorations: a bright Diego Rivera mural and giant panda rugs. But the decor couldn’t completely erase the austere environment that Stern Hall provided. Dorothy Walker, a former Stern resident, attributes this to the strict and paternalistic rules imposed on women students.

Walker: It was also a very stifling environment. First of all, of course, there were the Dean’s rules at the time, which were very in loco parentis.

Narration: Walker was a student in the 1940s, when the University took that phrase — in loco parentis — very seriously. School administrators saw their role as surrogate parents for students, especially women. And in Walker’s case, that meant a strict parent.

Walker: Women basically could not leave their dorms in the night, in the evening unless they were going to the library, and you had to be home by 10:15 if you were going to the library. You could sign out for an evening event, but basically if you were not home by midnight basically, you were locked out and you were in serious trouble. And there was a whole system of punishments and a board you would meet with if you ever violated the rules, so it was very strict.

Narration: The comparison to parental figures was so strong that students even referred to their chaperones as “dorm mothers” and “house mothers.” While some, like Walker, chafed under these watchful eyes, others embraced the bonds.

Donnelly/Voiceover: The sorority was like a family; you don’t go every place with your family when you are growing up, and yet there was always a family to come home to.

Narration: That’s Shanna Farrell reading from Ruth Norton Donnelly’s interview again. Donnelly lived in Sigma Kappa in the early 1920s, and described it as an integral part of her Berkeley experience. Before Berkeley built more dorms, many students like Donnelly looked to sororities and fraternities for places to live on campus.

But not everyone felt as welcome in the campus Greek system. Frank Inami, whose parents were Japanese, arrived in Berkeley on the eve of World War II:

Inami: …when I started at UC Berkeley in 1939, I stayed at the Japanese Students Club, because the fraternities and the sororities would not allow us in…

Narration: Many fraternities and sororities at Berkeley didn’t admit Jews or students of color. So some students, like Inami, created their own communities.

Inami: There was a Japanese Students Club, a special dormitory just for us…we used to call ourselves Jappa Sappa Chi…JSC. Japanese Students Club…We wanted to make it sound like one of the fraternities…There were about twenty-five of us, I guess, Japanese Americans. And like the fraternities, it was by invitation only.

Audio: (music)

Narration: By 1942, two-and-a-half years after Frank Inami started school at Berkeley, he and other Japanese American students were removed to internment sites away from the West Coast. Inami was eventually released, but he never returned to Cal.

Audio: (music)

Narration: It took a concerted effort by students and the administration to push for desegregation of the Greek system at Berkeley. Jackie Goldberg was a Cal student and activist in the 1960s. She applied to live in two places: a co-op and a dorm. She didn’t get into either. So Goldberg joined Delta Phi Epsilon, one of the few campus sororities at the time that accepted Jewish women.

Goldberg: I was the Panhellenic representative.

Rubens: Yes.

Narration: This means she sat on a council that made decisions for all campus Greek organizations. Along with the Dean of Women, Katherine Towle, Goldberg came up with a plan to make the sorority pledging process more inclusive.

Goldberg: …we cooked this up in her office, getting all of the sororities to sign the non-discrimination pledge…

Narration: At first, her fellow Greek members weren’t on board with the idea.

Goldberg: …they weren’t going to. And they weren’t going to basically because their national..

Rubens: National.

Goldberg: …controlled this decision.

Narration: By the way, that’s interviewer Lisa Rubens you hear in the background.

Goldberg: And she and I said, “Well, these young women like to think of themselves as liberals, as not racists. Why don’t we let them see the face of racism?”

Narration: So Goldberg and Dean Towle invited the national leaders of the sororities to a forum at the campus Panhellenic Council.

Goldberg: We had them all come, and these Southern white women just horrified these young girls by talking about [imitating a Southern accent] their rights to pick their friends and their rights to pick whom they associate with.

Narration: Goldberg hoped that her fellow Berkeley students, when confronted with the beliefs of those dictating membership policies, would break from the national practices.

Goldberg: And every one of the sororities signed after those women left. They just didn’t want to have anything to do with that.

Rubens: So they did all sign?

Goldeberg: They all signed.

Rubens: Oh, no kidding?

Goldberg: Yeah.

Audio: (music)

Narration: By the early 1960s, a postwar boom had expanded the UC system, forcing the University to finally build more extensive housing options. Of course, the fight for inclusion wasn’t over. For students with disabilities, there were still barriers to campus housing — even with the new dorms. Where could a student in a wheelchair live? Or a student with a visual impairment? These were the questions Edward V. Roberts asked when he arrived on Berkeley’s campus in 1962. He was the University’s first student with severe disabilities.

Roberts: But it wasn’t going to be easy, oh my God. The biggest obstacle became real soon, [labored breathing] where would I live? And I think we almost gave up because of that.

Narration: Roberts contracted polio as a child, and the illness left him with quadriplegia. He needed housing that could hold the iron lung which helped stabilize his breathing. He also needed attendants around-the-clock. In an era before the Americans with Disabilities Act, these accommodations made his housing search more difficult.

Roberts: It seemed like wherever we went, it was like, those places are too freaked out to deal with me.

Narration: Finally, Roberts met Dr. Henry Bruyn. Dr. Bruyn was the medical director of the Student Health Service at Berkeley. He suggested that Roberts live at Cowell Memorial Hospital, an ivy-covered student infirmary on the east side of campus.

Roberts: He said, “Why don’t we open the hospital? And you could live here.” And I started saying, “But I could live there like a dorm, right?” I said, “I know about hospitals; I don’t want to live in a hospital.” And he said, “We can work those things out.”

Narration: Roberts was worried about living at Cowell, because until then, the hospital only temporarily housed students recovering from surgery or who had illnesses like measles. He was looking for a community of his own.

Roberts was the first student to live at Cowell full time, but he was not the last. Over the next decade, many others came to call the hospital home as part of the Cowell Residence Program. Their quest for housing informed the Disabled Rights and Independent Living Movement on campus, which began in the late 1960s.

Then, in 1972, UC Berkeley students with disabilities pushed for even greater inclusivity by advocating for off-campus housing. This became the Center for Independent Living.

Audio: (music and noises from moving day)

Narration: It took nearly one hundred years for Berkeley to build the large-scale student housing we now associate with undergraduate move-in day.

Although a 2016 survey from Berkeley’s Office of Planning and Analysis reported that the number of Cal freshmen who experienced “inconsistent access to housing” is at 8 percent, challenges remain. And the fact that the Bay Area has the most expensive rental market in the country, directly impacts Cal students.

But, housing has improved at Berkeley. Blackwell Hall, Berkeley’s newest dorm, opened just in time for the 2018 school year. And in a recent message, Chancellor Carol Christ reinforced her commitment to expanding student housing.

The ongoing challenge of student housing highlights the long struggle to create community at Berkeley. But the history of student housing at UC Berkeley also demonstrates the key roles Cal students and administrators played in pushing for social justice on their campus and in their community.

Audio: (noises from moving day)

Narration: Which brings us back to moving day here at UC Berkeley, where a new class of freshmen are building their own campus community, and defining the issues that will shape their experiences, and the mark they leave on Cal.

Audio: (noises from moving day fade out) (music)

Meeker: This podcast was written and narrated by Amanda Tewes, with assistance from Shanna Farrell, Francesca Fenzi, and Oral History Center staff. Editing by Francesca Fenzi, and special assistance by Allie Cheroutes. Digitization by David Dunham and student employees. The Berkeley Remix theme music by Paul Burnett, and additional music by Blue Dot Sessions. Special thanks to The Bancroft Library. All interviews in this episode are from the Oral History Center collections. To learn more about these interviews, visit our website listed in the show notes. I’m Martin Meeker. Thank you for listening to The Berkeley Remix, and please join us next time!

Peter J. Taylor: The Getty Trust from a Trustee’s Perspective, 2005-2017

As part of an ongoing partnership between the Oral History Center and the Getty Trust, we recently conducted an interview with a former member of the J. Paul Getty Trust Board of Trustees: Peter J. Taylor.

Peter J. Taylor is president of ECMC [Education Credit Management Corporation] Foundation, and served on the Board of Trustees for the Getty Trust from 2005 to 2017. Mr. Taylor grew up in Los Angeles, California, and attended University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) in the 1970s. He is a graduate of the Coro Fellowship Program and completed his master’s degree at Claremont Graduate School. Taylor then worked as legislative staff for California Assemblyman Mike Roos. He transitioned to finance and worked for the Lehman Brothers until the 2008 Recession. Taylor served as the CFO of the University of California from 2009 to 2014, and then joined ECMC Foundation in 2014. In addition to the Getty Trust, Taylor has served on the boards of the James Irvine Foundation, the UCLA Alumni Association, the Ralph M. Parsons Foundation, and has been a member of the California State University System Board of Trustees since 2015. He was previously Alumni Representative on the University of California Board of Regents, and was chair of the UCLA African American Admissions and Retention Task Force.

Peter J. Taylor: The Getty Trust from a Trustee’s Perspective, 2005-2017

Taylor’s oral history interview offers insight into the management of the Getty Trust from the perspective of a trustee, as well as the challenges and successes of steering such a large arts organization. Taylor’s background in education and serving on the boards of other nonprofits bolstered his confidence in taking on the many challenges of the Getty Trust, though he admits he had little previous exposure to visual arts.

When Taylor joined the organization in 2005, the organization was facing an antiquities scandal, was the subject of an investigation by the California Attorney General, was struggling with internal management, and was receiving bad press from media outlets. The 2008 Recession also posed a problem for an arts institution that relied upon its endowment. With his background in finance, Taylor was an obvious choice for Chair of the Audit Committee, and helped lead the organization through the many difficult discussions about budget cuts and institutional priorities. Listen as Taylor recounts how the Recession impacted the Getty:

Taylor also points to the significant strides the Getty Trust has made in creating greater public impact through exhibitions that speak to the local community, education programs that bring more children to the museum, and providing more resources online – especially Getty images. In fact, he counts the move towards open content as one of the greatest achievements during his tenure as a trustee. Listen as Taylor discusses pushing for more open access resources at the Getty Trust:

Explore Peter J. Taylor’s oral history and learn more about the mission and history of the Getty Trust!

Sally Hibbard: Forty Years of Change at the J. Paul Getty Museum

Sally Hibbard is the former chief registrar at the J. Paul Getty Museum. She grew up in San Diego, California, and studied art history at Occidental College in the 1960s and 1970s. Hibbard joined the Getty Museum in 1974 as the secretary to the curator of decorative arts, Gillian Wilson. She became the registrar at the Getty Museum in 1975, leading the Registrar’s Department until her retirement in 2014.

Sally Hibbard: Forty Years of Change at the J. Paul Getty Museum

Sally Hibbard’s oral history interview opens a window into the early years at the J. Paul Getty Museum, the effect of Mr. Getty’s passing, and the various ways the organization has grown and changed over the years. Indeed, Hibbard was herself a changemaker at the Getty. She oversaw the development of the Registrar’s Department from a department of one to the backbone of the Getty Museum, with teams specializing in rights and reproductions, collections management, and exhibitions. She also directed the transition from paper to digital records for better management of the Getty’s collections and data.

In her role as chief registrar, Hibbard led the monumental task of moving collections from the Getty Villa to the new Getty Center in Brentwood in the 1990s. This initiative took several years and much planning. Listen as Hibbard recounts the first of these moving days:

Given its locations in the Los Angeles area, the Getty’s sites routinely face natural disasters like earthquakes and wildfires. Hibbard participated in discussions about how best to protect collections in the face of these emergencies. Listen as Hibbard recalls emergency preparedness at the Getty:

Explore Sally Hibbard’s oral history and gain important insight into the history of the J. Paul Getty Museum!