On Friday, January 31, early career faculty, graduate students, librarians, and others joined us for Publish or Perish Reframed: Navigating the New Landscape of Scholarly Publishing. The event, hosted by the Office of Scholarly Communication Services, aimed to help everyone understand the behind-the-scenes workings of scholarly publishing, especially for the early career researchers and students interested in publishing.

Why are we concerned about the state of scholarly publishing? Things are looking rather sunny for UC authors, who publish nearly 10% of all scholarly literature in the United States. However, there are actually a lot of tensions in the scholarly publishing ecosystem today, and the landscape can be confusing or murky. One of the tensions has to do with access to research, as 85% of journal articles being published each year are still stuck behind paywalls, thus slowing scientific discovery because only people who have subscriptions can access and read it. Subscription prices of commercial scholarly journals continue to increase, while university library collections budgets continue to shrink–further constricting access to knowledge. Another challenge is ongoing publishing expectations: PhD students, post-docs, and young faculty are under ongoing pressure to publish in the most prestigious journals available in order to receive promotion and tenure, even though many of these publishing venues continue to be the most closed and expensive to which libraries subscribe.

The publishing lifecycle, stakeholder power, and library budgets

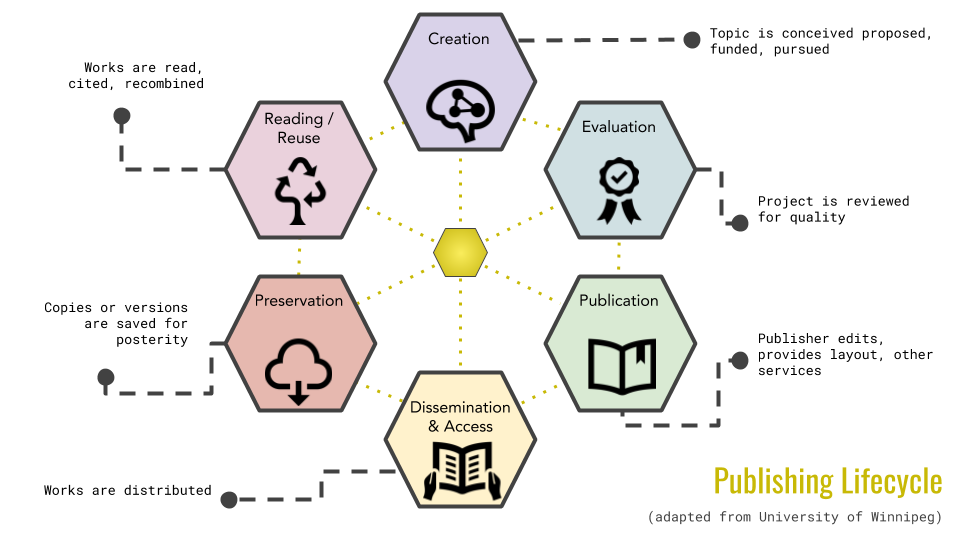

Rachael Samberg and Timothy Vollmer from the Office of Scholarly Communication Services kicked off the event by taking a closer look at the publishing lifecycle today. While this process can vary somewhat based on the nature of the research, there are some common aspects, such as (1) reading the works of others and then forming your own research, (2) creating a new knowledge product such as a written article, (3) submitting that work to a publisher which coordinates a peer review process, (4) publishing the work in a scholarly journal, (5) distributing the work via library subscriptions or open access, and (6) preserving the work.

The publishing lifecycle involves many different players, and power is not distributed equally amongst these various participants. For instance:

- The reading public or scholars at other institutions have an interest in reading the outputs of scholarship, but little power in demanding how it’s made available. They can’t vote with their feet and decide not to read a journal article they need for their research, the way you could with a car that was too expensive, and for which an equivalent car might be available from another manufacturer for less.

- The author has an interest in producing good quality work, but is in some ways beholden to needing it to be selected by reputable journals to build reputation and achieve career advancement.

- Universities are interested in recruiting and retaining high profile scholars and students—and also grants and donor funds—and the reception of scholarship created at the institutions affect their ability to do this. The more prestigious the publications, the better this reflects on the universities, so there is some pressure universities can exert over authors about the journals in which their authors should publish.

- Funders like federal agencies and philanthropic foundations want the research they support to make a societal and global impact, and are therefore interested in how that research is disseminated. Funders can require dissemination of work product, but they can’t necessarily interfere with academic freedom about where to publish.

- Libraries want to purchase or license access to the content to provide it to the readers at their universities or institutions. But they’re not the ones creating the content as a way to try to control costs, and further if they refuse to purchase or license content, their authors and universities will be affected

- Scholarly societies are interested in putting out high quality scholarship, but they may also wish to generate enough money to fund not only their publishing efforts but also other society operations like conferences or education—so this limits how “low they can go,” so to speak in terms of the price point for what they publish.

- Most of the market power—at least on the surface—lies with large third party commercial publishers, who stand poised to generate substantial profits in exchange for the opportunity to publish in or read their valued journals.

Many institutions aren’t lucky enough to have the millions of dollars needed to spend on getting subscriptions to high priced journal content. And if they don’t have that money and can’t subscribe, then the people affiliated with that institution can’t read the latest scholarship. In turn, if the institution’s scholars don’t have access to it, then their ability to use it to help them come up with new ideas and insights in their own scholarship is severely limited. So, scientific progress is hampered.

Open access publishing approaches

In order to understand how any stakeholders can encourage an open outcome, we’ve first got to understand what types of open access financial strategies exist. How is OA funded? If we replace the subscription system with OA end products, why would publishers stay in the game? If publishers are going to invest time and effort in publishing, how do they recover costs in an OA universe?

Before we dive into OA funding approaches, one important thing to keep in mind is that publishing a scholarly article or book open access does not mean foregoing peer review or any of the other stringent editorial processes that ensure high quality scholarship. In fact, peer review can be even carried out in more cost effective ways for OA journals. At its core, open access is just an outcome: Scholarship is published online in a way that can be read and used by anyone, and without any financial, legal, or technical barriers other than gaining access to the Internet, itself.

Okay, so on to who gets paid and how. One approach to achieving OA is “green open access.” This “flavor” of OA means that authors or institutions make works that would otherwise only be available via a subscription freely available by depositing certain versions of their scholarship into online repositories, typically institutional repositories run by a researcher’s university (like the UC’s eScholarship), or even a funder repository like the NIH’s PubMed Central.

The version that can be deposited depends in part on the specific terms of the publication agreement the author signs with the publisher. You might be wondering, why on earth does it matter what publication agreement says? Well, in exchange for the publisher agreeing to publish a journal article—they often demand that authors relinquish some or all relevant rights to share or reuse the work. So, in order to publish in most commercial journals, the author must transfer their copyright to the journal. And unless their publication agreement reserves certain rights for the author, the copyright transfer means the author will no longer retain the necessary rights to publicly share the final article—even on their own course website or institutional repository.

So, if authors assign all their rights to publishers, why are they permitted to deposit certain versions of their work in a repository? There are two reasons. First, many publishers’ agreements now provide authors with permission to self archive what’s called the “post-print”— the final peer-reviewed article but that lacks the publisher’s final copy-editing and formatting. Second, institutional OA policies preemptively secure the rights for universities to host works notwithstanding the language of author publication agreements. These policies can attach to articles before an author ever signs a publication agreement.

This is what the UC’s Open Access Policy does. As a UC author, you have a right to deposit your post-print of your article into UC’s institutional repository called eScholarship at the time of publication. The UC takes a license to display the peer-reviewed version of your work, such that any publication agreement you later sign is subject to the UC’s pre-existing right..

There’s also “gold open access.” Gold OA means that what the publisher puts out online on its website—immediately upon publication of the article, whether in print or online—is free access to the final, publisher-version of the article. Typically these articles are shared under a Creative Commons license. Some gold OA publishers recoup production costs via charges for authors to publish (“article processing charges” or “book processing charges”) rather than having readers (or libraries) pay to access and read it. In general, gold OA is a system in which the author pays, rather than the reader paying. At the same time, the fees to be paid for publishing don’t actually have to be paid by the author. They can be covered by various sources, such as: research accounts, research grants, the university, the monies the libraries previously were spending on subscriptions to that journal, scholarly societies, and consortia. (Read on for the program the UC Berkeley Library runs to cover these fees.)

There’s also a type of gold open access that does not involve APCs. Here, the publisher provides permanent and free access to readers with neither author fees nor reader fees. Typically a society, organization, government, or endowment would be necessary to cover the cost of publication.

Empowering universities and authors

We explored what UC Berkeley is doing to leverage these open access models to make scholarship more available. The UC is pursuing a wide array of strategies to improve access to research, including many outlined in the Pathways to Open Access toolkit. To be sure, UC authors have been publishing their articles open access for years, and UC was one of the early institutions with a post-print, green open access policy. But Pathways to Open Access analyzed a panoply of additional funding strategies, and made recommendations for a plurality of approaches.

One example of a new strategy being pursued is negotiating transformative agreements. These types of arrangements have been supported by the UC systemwide faculty senate library committee, who pushed ahead the goal of replacing subscription-based publishing with open access by releasing a declaration of rights and principles to transform scholarly communication. These principles are now guiding the UC libraries in pursuing transformative publishing agreements.

The UC’s goal with transformative agreements is to both changing subscription agreements into agreements that enable open access publishing, and also reduce how much we are spending on the publishing enterprise to begin with. It’s important to emphasize that transformative agreements are just one of the ways the UC campuses and the UC Berkeley library are pursuing open access.

The University of California has been exploring different types of flexible models for transformative agreements. For instance, the agreement the UC has pursued with Cambridge University Press is a multi-payer model, where both libraries and authors (if they have grant funds) contribute to the open access publishing fee.

From the author’s perspective, the Cambridge transformative workflow attempts to minimize intrusion into the publishing process, while still working to incorporate authors into the payment process in some form so they understand the costs of publishing in a new landscape. Authors still choose their journal, submit their manuscript to the journal, and pass through the peer review process as normal; we’re not asking them to change how they do any of those things, especially how they select a journal. Once a manuscript is accepted by a journal with a publisher with whom we have a transformative agreement, then the author is asked to choose whether to publish open access or to opt out of the agreement and publish closed access. Of course, the Library prefers for authors to publish open access, and our intention is to make that the default option, but we don’t require this.

Assuming an author chooses to publish open access, they will be asked to coordinate payment of an APC. In general, this APC is discounted from the list price that the publisher may currently be charging. The library commits to paying a portion of every open access fee. We then ask the author whether they have research funding available which may be used to pay for publication. If they do, then the author pays the remainder of the OA fee. If they do not have research funding available for this purpose, then the library pays the remainder of the fee on the author’s behalf. In this way, authors engage with the payment process, and they contribute a portion of the cost if they have funding available to do so. However, authors without research funding are not disadvantaged, and we never ask an author to reach into their own pockets to make a payment.

Even if the UC hasn’t entered into a transformative agreement with a publisher, there are many other opportunities for authors to get involved in impactful OA decision-making. We discussed that one thing UC Berkeley authors can do right now is to take part in the existing UC open access publishing mechanisms, such as by depositing post-prints in eScholarship an. We also mentioned the UC Berkeley Library program called the Berkeley Research Impact Initiative (BRII) that covers up to $2500 of an APC an author is charged for publishing in a fully open access journal.

Another way authors can empower themselves as scholars is by retaining various rights in the publishing process. Making smart decisions about copyright can help scholarly authors maximize the impact of their research by promoting greater readership and reuse . In most cases, the author of an article is the copyright holder, and authors maintain their copyright to the scholarship until they transfer all or certain rights to a publisher. Now, the publisher might ask for a full transfer of copyright. But as an author you don’t necessarily have to just sign the agreement a publisher presents to you. You can ask for an alternative wording, and sometimes they immediately just send you their alternate agreement with that change already baked in. Some publishers take a different approach through which authors keep their copyright and instead agree to share their work under an open license. For example, copyright in all Public Library of Science articles stays with the authors, but the authors agree to share the work under an open license, in this case the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license. This license permits unrestricted use and sharing provided the original author and source are credited. In the end, authors have choices to make, both in managing their rights through the author agreement, or even pursuing full open access journals that leverage open licensing.

Challenges in Publishing for Promotion and Tenure

Benjamin Hermalin, Vice Provost for the Faculty, discussed some of the tensions within scholarly publishing as they relate to promotion and tenure, and provided some advice to new authors in making their way through the publication process. While the Office of the Vice Chancellor for the Faculty reviews all outside letters in each tenure and promotion submission, he said there’s still some conservatism in how tenure and review committees assess a scholar’s publishing outputs and impact. Hermalin advised young researchers to take a measured approach by understanding the particular requirements and publishing practices for their specific field, and aim for publishing several publications in high quality journals relevant to their area.

Of course, the question keeps coming up: How does a researcher get published in the top journals? No one knows the complete answer to this, but authors need to be systematic, and diligent. Hermalin advocated that it’s more important to work toward becoming a major contributor to one or two areas than to be a minor contributor to several fields of research.

Hermalin also talked about some of the challenges researchers face in determining when to publish. He noted that while an author shouldn’t send something out before they’re ready, they also shouldn’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good: getting the research off your desk in a timely fashion is best for your academic profile and chances for tenure down the road. He also suggested that authors not split their scholarly output too thinly: it’s better to publish a few substantial, in-depth papers on a particular topic than several separate publications that individually cover too little of the research endeavor.

Open publishing: A View from the Faculty

Philip Stark, Professor of Statistics and Associate Dean of the Division of Math and Physical Sciences, provided an on-the-ground perspective of open science, OA publishing, and how he deals with copyright and publishing contracts with commercial publishers. Stark showed several examples of how he marks up publishing agreements since he no longer gives any publisher an exclusive right to publish. He also showed how to strike language and amend it to retain copyright and other publishing rights, and said in his experience, most publishers have accepted these changes.

Professor Stark discussed one paper that he published open access through help from BRII. The paper analyzed gender bias in student evaluations, and Stark and his co-authors wanted it to be open access. But Philip was concerned that if they published it in an open access publication, his co-authors—who were a junior faculty and PhD student at the time—might not get as much recognition or impact from the paper than if they were to shoot for publishing in one of journals considered to be “high impact” under certain standards.j. However, the initial fears about publishing on ScienceOpen were unfounded, as the paper has since been widely accessed, cited, and freely downloaded over 70,000 times. Stark said he earned a much bigger impact publishing open access there than if it’d been published in a commercial journal.

Finally, Professor Stark discussed academic freedom in relation to faculty publishing choices. While many think the concept of academic freedom means that researchers are privileged with the ability to work on what they find interesting and important without outside pressure from the university administration, the reality is that faculty—especially early career researchers—are under ongoing pressure to publish in journals that will secure them tenure, or to obtain grants to support their (or their students’) research. In this sense, faculty publishing decisions are driven more by economic forces than the principle of academic freedom. Stark said that this temptation to publish in the most prestigious journal to advance your career is a persistent moral hazard because it challenges the more noble perceptions we have about academic pursuits and how the work of academics benefits science, and the public interest.

Certainly, no one had all the answers for simplifying the complexities of scholarly publishing, but by understanding the driving forces and power dynamics, early career authors can make informed choices that will carry their scholarship far both in impact and in their professional advancement.