It took centuries before Italy could codify and proclaim Italian as we know it today. The canonical author Dante Alighieri, was the first to dignify the Italian vernaculars in his De vulgari eloquentia (ca. 1302-1305). However, according to the Tuscan poet, no Italian city—not even Florence, his hometown—spoke a vernacular “sublime in learning and power, and capable of exalting those who use it in honour and glory.”[1] Dante, therefore, went on to compose his greatest work, the Divina Commedia in an illustrious Florentine which, unlike the vernacular spoken by the common people, was lofty and stylized. The Commedia (i.e. Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso) marked a linguistic and literary revolution at a time when Latin was the norm. Today, Dante and two other 14th-century Tuscan poets, Petrarch and Boccaccio, are known as the three crowns of Italian literature. Tuscany, particularly Florence, would become the cradle of the standard Italian language.

In his treatise Prose della volgar lingua (1525), the Venetian Pietro Bembo champions the Florentine of Petrarch and Boccaccio about 200 years earlier. Regardless of the ardent debates and disagreements that continued throughout the Renaissance and beyond, Bembo’s treatise encouraged many renowned poets and prose writers to compose their works in a Florentine that was no longer in use. Nevertheless, works continued to be written in many dialects for centuries (Milanese, Neapolitan, Sicilian, Sardinian, Venetian and many more), and such is the case until this day. But which language was to become the lingua franca throughout the newly formed Kingdom of Italy in 1861?

With Italy’s unification in the 19th century came a new mission: the need to adopt a common language for a population that had spoken their respective native dialects for generations.[2] In 1867, the mission fell to a committee led by Alessandro Manzoni, author of the bestselling historical novel I promessi sposi (The Betrothed, 1827). In 1868, he wrote to Italy’s minister of education Emilio Broglio that Tuscan, namely the Florentine spoken among the upper class, ought to be adopted. Over the years, in addition to the widespread adoption of The Betrothed as a model for modern Italian in schools, 20th-century Italian mass media (newspaper, radio, and television) became the major diffusers of a unifying national language.

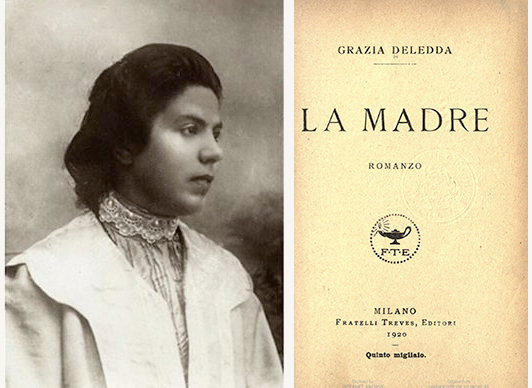

Grazia Maria Cosima Deledda (1871-1936), the author featured in this essay, is one of the millions of Italians who learned standardized Italian as a second language. Her maternal language was Logudorese Sardo, a variety of Sardinian. She took private lessons from her elementary school teacher and composed writing exercises in the form of short stories. Her first creations appeared in magazines, such as L’ultima moda between 1888 and 1889. She excelled in Standard Italian and confidently corresponded with publishers in Rome and Milan. During her lifetime, she published more than 50 works of fiction as well as poems, plays and essays, all of which invariably centered on what she knew best: the people, customs and landscapes of her native Sardinia.

The UC Berkeley Library houses approximately 265 books by and about Deledda as well as our digital editions of her novel La madre (The Mother). It was originally serialized for the newspaper Il tempo in 1919 and published in book form the following year. Deledda recounts the tragedy of three individuals: the protagonist Maria Maddalena, her son and young priest Paulo, and the lonely Agnese with whom Paulo falls in love. The mother is tormented at discovering her son’s love affair with Agnese. Three English translations of La madre have appeared, however, it was the 1922 translation by Mary G. Steegman (with a foreword by D.H. Lawrence) that was most influential in providing Deledda with international renown.

Deledda received the 1926 Nobel Prize for Literature “for her idealistically inspired writings which, with plastic clarity, picture the life on her native island and with depth and sympathy deal with human problems in general.”[3] To this day, she is the only Italian female writer to receive the highest prize in literature. Here are the opening lines of Deledda’s speech in occasion of the award conferment in 1927:

Sono nata in Sardegna. La mia famiglia, composta di gente savia ma anche di violenti e di artisti primitivi, aveva autorità e aveva anche biblioteca. Ma quando cominciai a scrivere, a tredici anni, fui contrariata dai miei. Il filosofo ammonisce: se tuo figlio scrive versi, correggilo e mandalo per la strada dei monti; se lo trovi nella poesia la seconda volta, puniscilo ancora; se va per la terza volta, lascialo in pace perché è un poeta. Senza vanità anche a me è capitato così.

I was born in Sardinia. My family, composed of wise people but also violent and unsophisticated artists, exercised authority and also kept a library. But when I started writing at age thirteen, I encountered opposition from my parents. As the philosopher warns: if your son writes verses, admonish him and send him to the mountain paths; if you find him composing poetry a second time, punish him once again; if he does it a third time, leave him alone because he’s a poet. Without pride, it happened to me the same way. [my translation]

The Department of Italian Studies at UC Berkeley dates back to the 1920s. Nevertheless, Italian was taught and studied long before the Department’s foundation. “Its faculty—permanent and visiting, present and past—includes some of the most distinguished scholars and representatives of Italy, its language, literature, history, and culture.” As one of the field’s leaders and innovators both in North America and internationally, the Department retains its long-established mission of teaching and promoting the language and literature of Italy and “has broadened its scope to include multiple disciplinary and interdisciplinary perspectives to view the country, its language, and its people” from within Italy and globally, from the Middle Ages to the present day.[4]

Contribution by Brenda Rosado

PhD Student, Department of Italian Studies

Source consulted:

- Dante Alighieri, De Vulgari Eloquentia, Ed. and Trans. Steven Botterill, p. 41

- Mappa delle lingue e gruppi dialettali d’italiani, Wikimedia Commons (accessed 12/5/19)

- From Nobel Prize official website: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/1926/summary

See also the award presentation speech (on December 10, 1927) by Henrik Schück, President of the Nobel Foundation: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/1926/ceremony-speech (accessed 12/5/19) - Department of Italian Studies, UC Berkeley (accessed 12/5/19)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: La madre

Title in English: The Woman and the Priest

Author: Deledda, Grazia, 1871-1936

Imprint: Milano : Treves, 1920.

Edition: 1st

Language: Italian

Language Family: Indo-European, Romance

Source: HathiTrust (University of California)

URL: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/006136134

Other online editions:

- La madre. 1st ed. Milano : Treves, 1920. (Sardegna Digital Library)

- The Woman and the Priest. Translated into English by M.G. Steegman; foreword by D.H. Lawrence. London, J. Cape, 1922. (HathiTrust)

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- La madre. 1st ed. Milano : Treves, 1920.

- La Madre : (The woman and the priest), or, The mother. Translated into English by M.G. Steegman; foreword by D.H. Lawrence; with an introduction and chronology by Eric Lane. London : Dedalus, 1987.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

![The Languages of Berkeley [fan]](https://update.lib.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/fan_languages-450px.jpg)