Some of you know that I’m rather delighted by maps. I find them fascinating for many reasons, from their visual beauty to their use of the lie to impart truth, to some of their colors and onward. I think that maps are wonderful and great and superbulous even as I unhappily acknowledge that some are dastardly examples of horror.

What I’m writing about today is the process of taking a historical map (yay!) and pinning it on a contemporary street map in order to use it as a layer in programs like StoryMaps JS or ArcGIS, etc. To do that, I’m going to write about

Picking a Map from Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia accounts and “map” markup

Warping the map image

Loading the warped map into ArcGIS Online as a layer

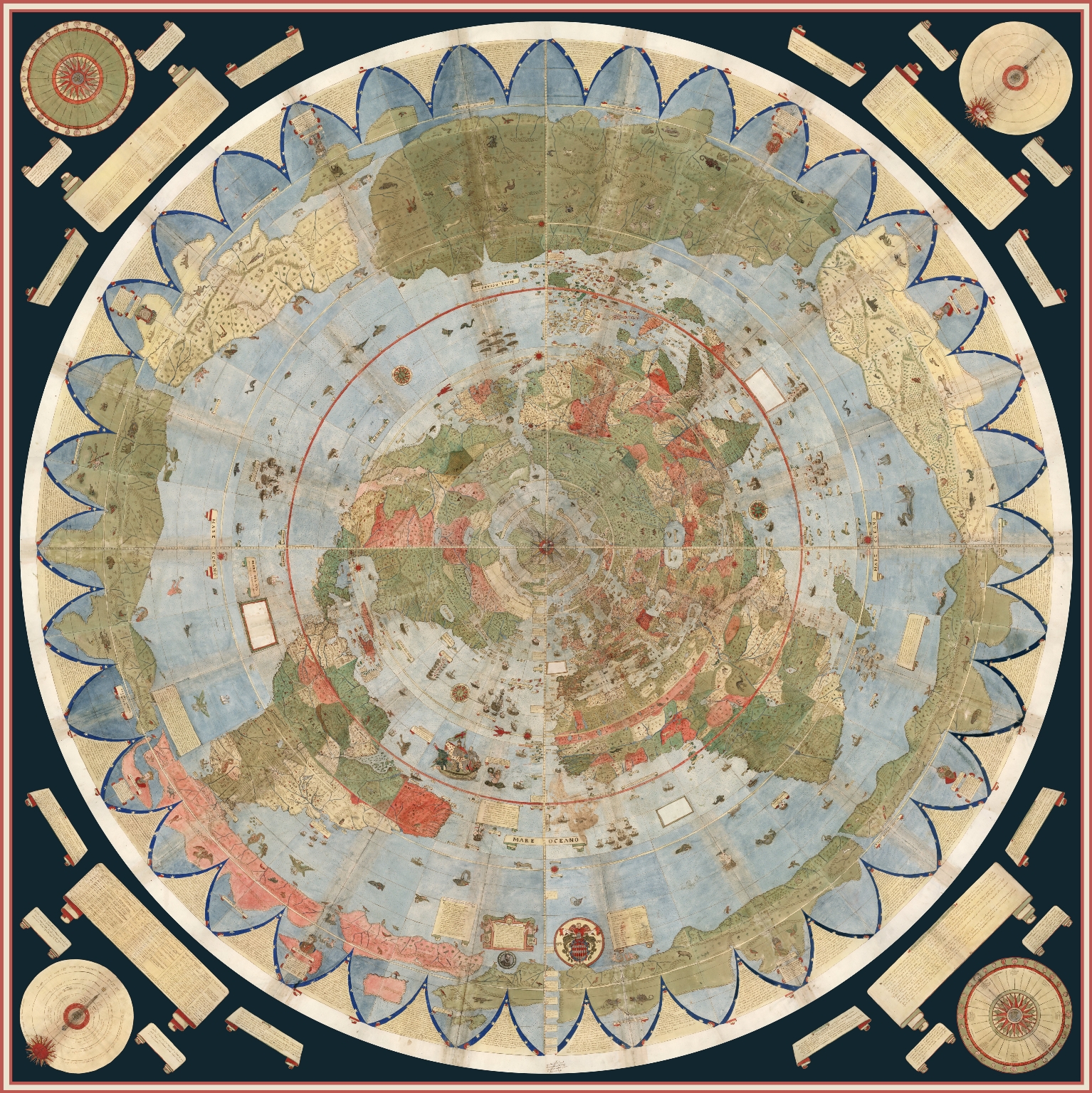

But! Before I get into my actual points for the day, I’m going to share one of my very favorite maps:

What is Map Warping

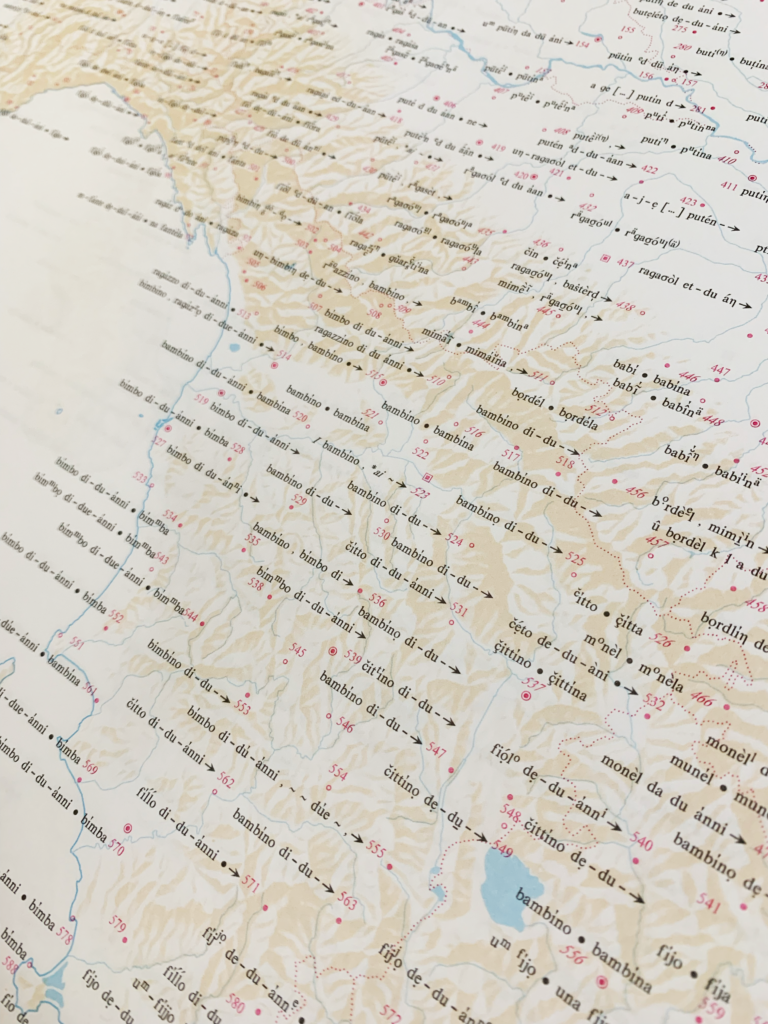

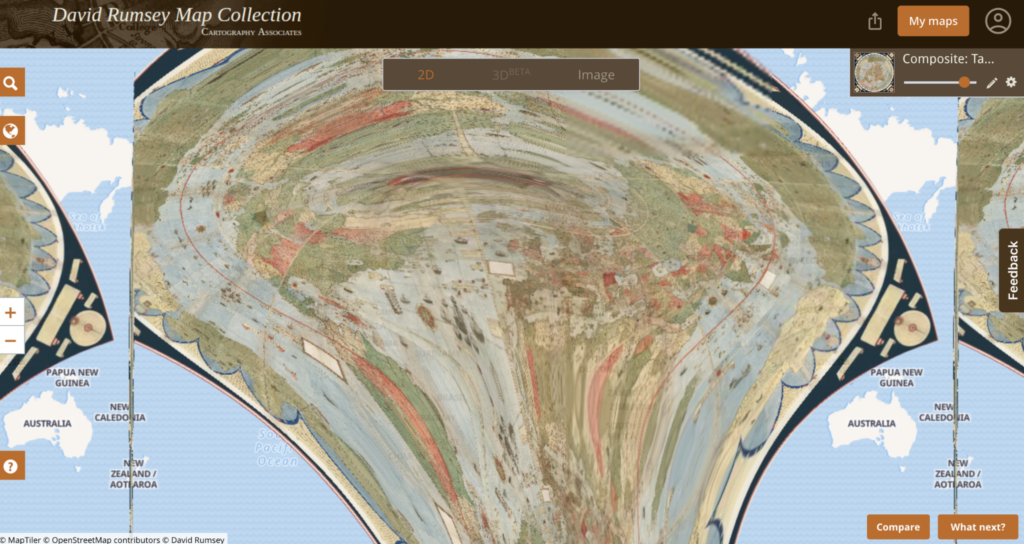

While this is in fact one of my favorite maps and l use many an excuse to talk about it, I did actually bring it up for a reason: the projection (i.e., azimuthal) is almost impossible to warp.

As stated, warping a map is when one takes a historical map and pins it across a standard, contemporary “accurate” street map following a Mercator projection, usually for the purpose of analysis or use in a GIS program, etc.

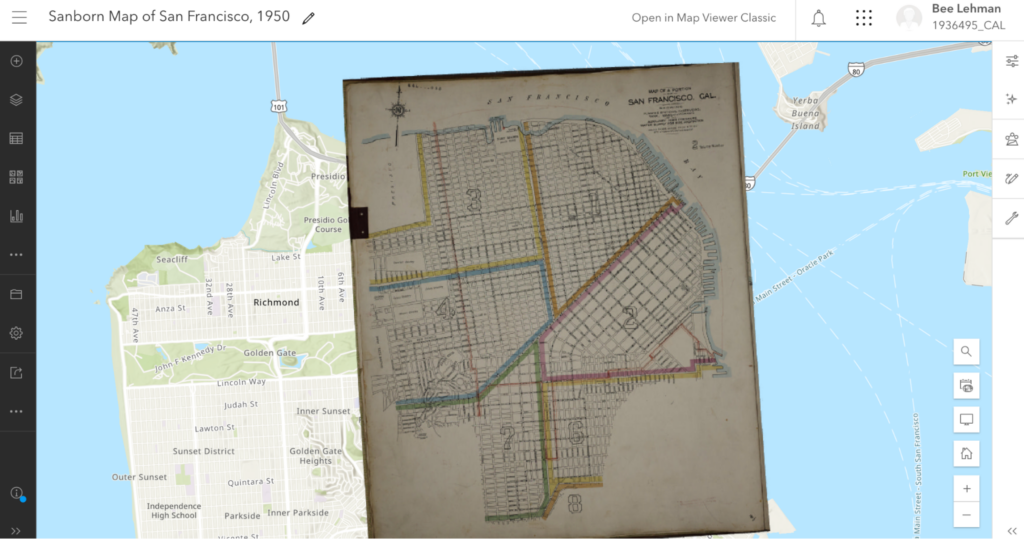

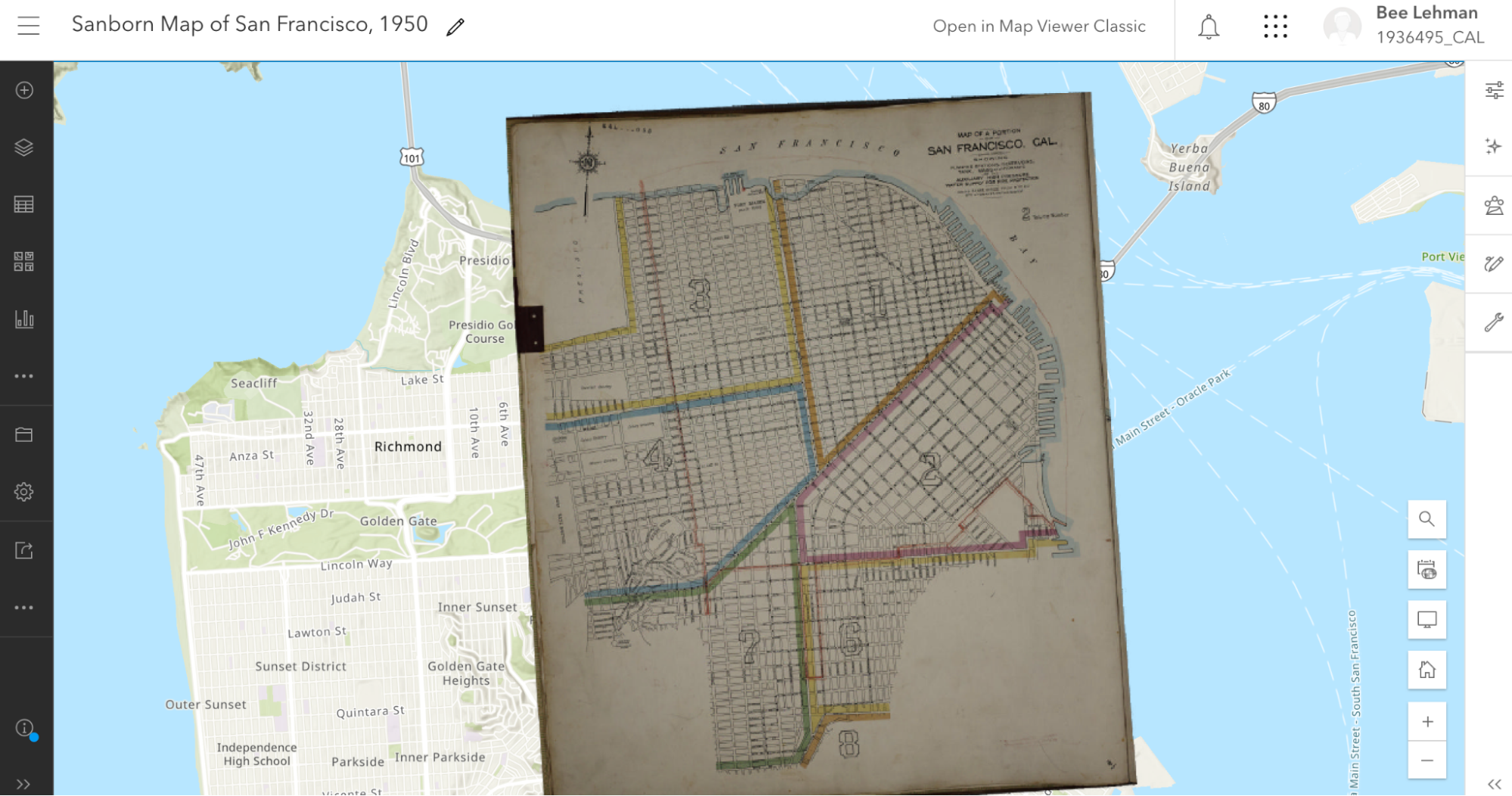

Here, for example, is the 1913 Sanborn fire insurance map layered in ArcGIS Online maps.

I’ll be writing about how I did that below. For the moment, note how the Sanborn map is a bit pinched at the bottom and the borders are tilted. The original map wasn’t aligned precisely North and the process of pinning it (warping it) against an “accurate” street map resulted in the tilting.

That was possible in part because the Sanborn map, for all that they’re quite small and specific, was oriented along a Mercator projection, permitting a rather direct rectification (i.e., warping).

In contrast, take a look at what happens in most GIS programs if one rectifies a map—including my favorite above—which doesn’t follow a Mercator projection:

Warping a Mercator Map

This still leaves the question: How can one warp a map to begin with?

There are several programs that you can use to “rectify” a map. Among others, many people use QGIS (open access; Windows, macOS, Linux) or ArcGIS Pro (proprietary;Windows only).

Here, I’m going to use Wikimaps Warper (for more info), which connects up with Wikimedia Commons. I haven’t seen much documentation on the agreements and I don’t know what kind of server space the Wikimedia groups are working with, but recently Wikimedia Commons made some kind of agreement with Map Warper (open access, link here) and the resulting Wikimaps Warper is (as of the writing of this post in November 2024) in beta.

I personally think that the resulting access is one of the easiest to currently use.

And on to our steps!

Picking a Map from Wikimedia Commons

To warp a map, one has to have a map. At the moment, I recommend heading over to Wikimedia Commons (https://commons.wikimedia.org/) and selecting something relevant to your work.

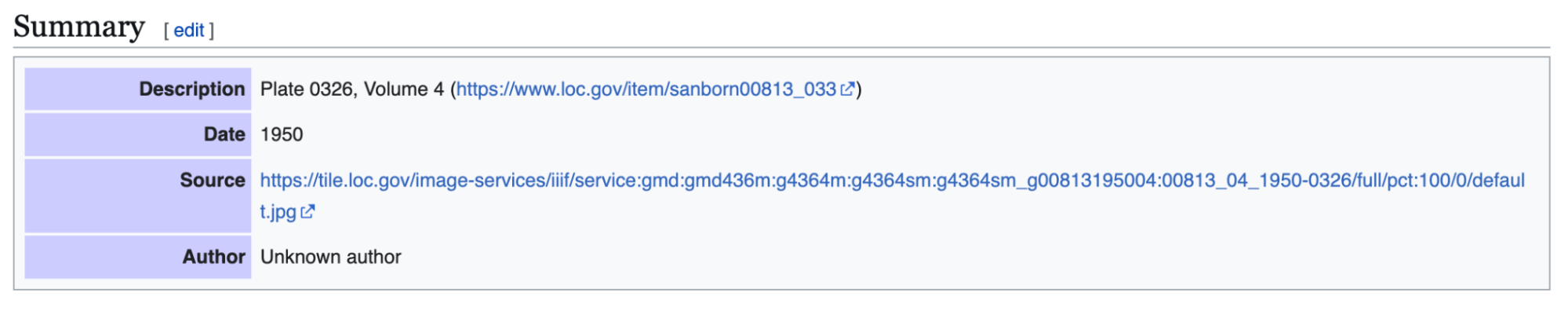

Because I’m planning a multi-layered project with my 1950s publisher data, I searched for (san francisco 1950 map) in the search box. Wikimedia returned dozens of Sanborn Insurance Maps. At some point (22 December 2023) a previous user (Nowakki) had uploaded the San Francisco Sanborn maps from high resolution digital surrogates from the Library of Congress.

Looking through the relevant maps, I picked Plate 0000a (link) because it captured several areas of the city and not just a single block.

When looking at material on Wikimedia, it’s a good idea to verify your source. Most of us can upload material into Wikimedia Commons and the information provided on Wikimedia is not always precisely accurate. To verify that I’m working with something legitimately useful, I looked through the metadata and checked the original source (LOC). Here, for example, the Wikimedia map claims to be from 1950 and in the LOC, the original folder says its from 1913.

Feeling good about the legality of using the Sanborn map, I was annoyed about the date. Nonetheless, I decided to go for it.

Moving forward, I checked the quality. Because of how georecification and mapping software works, I wanted as high a quality of map as I could get so that it wouldn’t blur if I zoomed in.

If there wasn’t a relevant map in Wikimedia Commons already, I could upload a map myself (and likely will later). I’ll likely talk about uploading images into Wikimedia Commons in … a couple months maybe? I have so many plans! I find process and looking at steps for getting things done so fascinating.

Wikimedia Accounts and Tags

Before I can do much with my Sanborn map, I need to log in to Wikimedia Commons as a Wiki user. One can set up an account attached to one of one’s email accounts at no charge. I personally use my work email address.

Note: Wikimedia intentionally does not ask for much information about you and states that they are committed to user privacy. Their info pages (link) states that they will not share their users’ information.

I already had an account, so I logged straight in as “AccidentlyDigital” … because somehow I came up with that name when I created my account.

Once logged in, a few new options will appear on most image or text pages, offering me the opportunity to add or edit material.

Once I picked the Sanborn map, I checked

- Was the map already rectified?

- Was it tagged as a map?

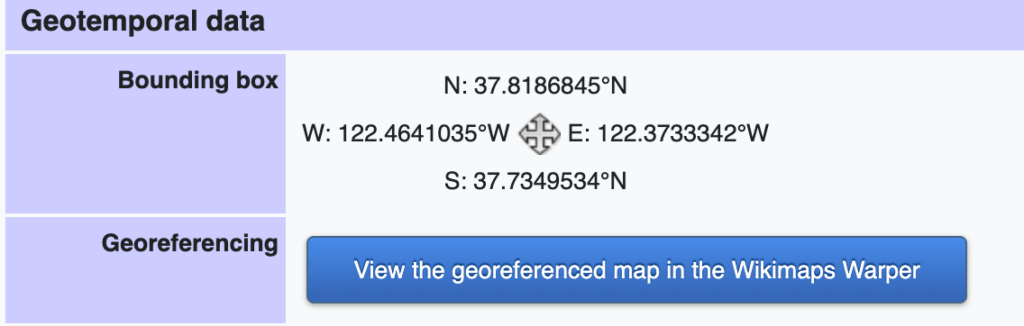

If the specific map instance has already been rectified in Wikimaps, then there should be some information toward the end of the summary box that has a note about “Geotemporal data” and a linked blue bar at the bottom to “[v]iew the georeferenced map in the Wikimaps Warper.”

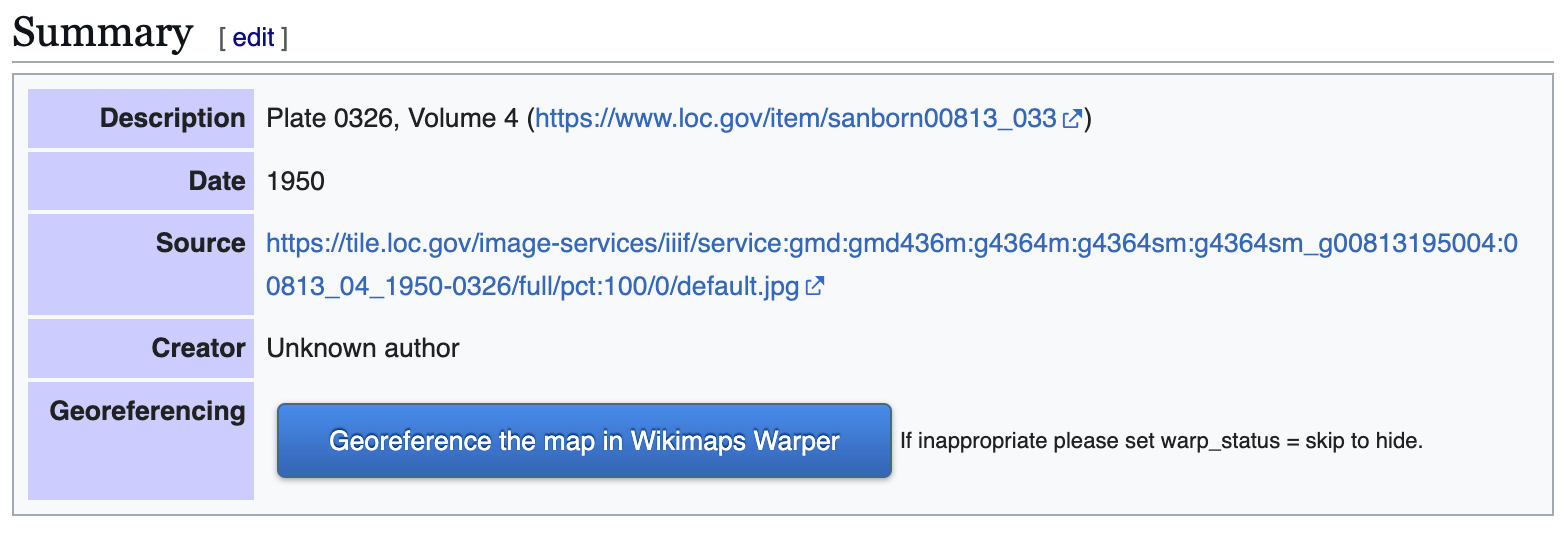

If that doesn’t exist, then one might get a summary box that is limited to a description, links, dates, etc., and no reference to georeferencing.

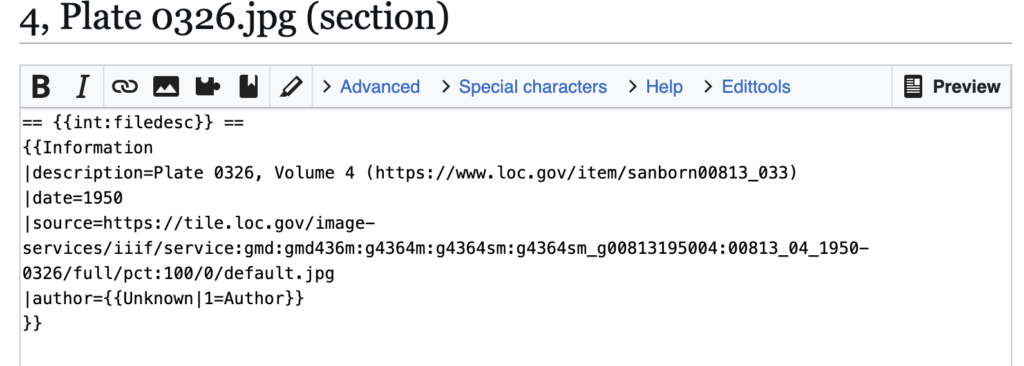

In consequence, I needed to click the “edit” link next to “Summary” above the description. Wikimedia will then load the edit box for only the summary section, which will appear with all the text from the public-facing box surrounded by standard wiki-language markup.

All I needed to do was change the “{{Information” to “{{Map” and then hit the “Publish” button toward the bottom of the edit box to release my changes.

The updated, public-facing view will now have a blue button offering to let users “Georeference the map in Wikimaps Warper.”

Once the button appeared, I clicked that lovely, large, blue button and went off to have some excellent fun (my version thereof).

Warping the map

When I clicked the “Georefence” button, Wikimedia sent me away to Wikimaps Warper (https://warper.wmflabs.org/). The Wikimaps interface showed me a thumbnail of my chosen map and offered to let me “add this map.”

I, delighted beyond measure, clicked the button and then went and got some tea. Depending on how many users are in the Wikimaps servers and how big the image file for the map is, adding the file into the Wikimaps servers can take between seconds and minutes. I have little patience for uploads and almost always want more tea, so the upload time is a great tea break.

Once the map loaded (I can get back to the file through Wikimedia Commons if I leave), I got an image of my chosen map with a series of options as tabs above the map.

Most of the tabs attempt to offer options for precisely what they say. The “Show” tab offers an image of the loaded map.

- Edit allows me to edit the metadata (i.e., title, cartographer, etc.) associated with the map.

- Rectify allows me to pin the map against a contemporary street map.

- Crop allows me to clip off edges and borders of the map that I might not want to appear in my work.

- Preview allows me to see where I’m at with the rectification process.

- Export provides download options and HTML links for exporting the rectified map into other programs.

- Trace would take me to another program with tracing options. I usually ignore the tab, but there are times when it’s wonderful.

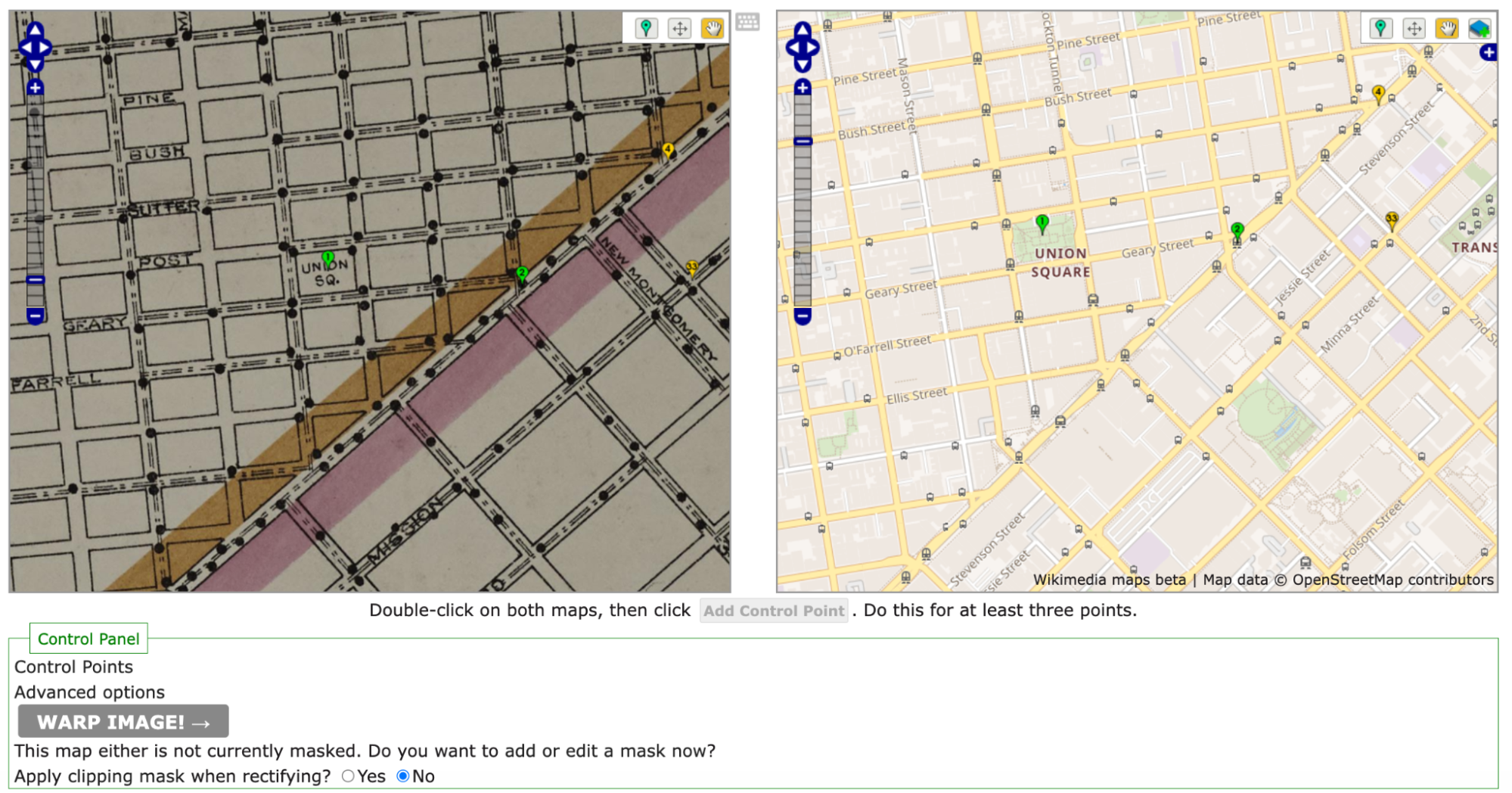

The Sanborn map didn’t have any information I felt inclined to crop, so I clicked straight onto the “Rectify” tab and got to work.

As noted above, the process of rectification involves matching the historic map against a contemporary map. To start, one needs at least four pins matching locations on each map. Personally, I like to start with some major landmarks. For example, I started by finding Union Square and putting pins on the same location in both maps. Once I was happy with my pins’ placement on both maps, I clicked the “add control point” button below the two maps.

Once I had four pins, I clicked the gray “warp image!” button. The four points were hardly enough and my map curled badly around my points.

To straighten out the map, I went back in and pinned the four corners of the map against the contemporary map. I also pinned several street corners because I wanted the rectified map to be as precisely aligned as possible.

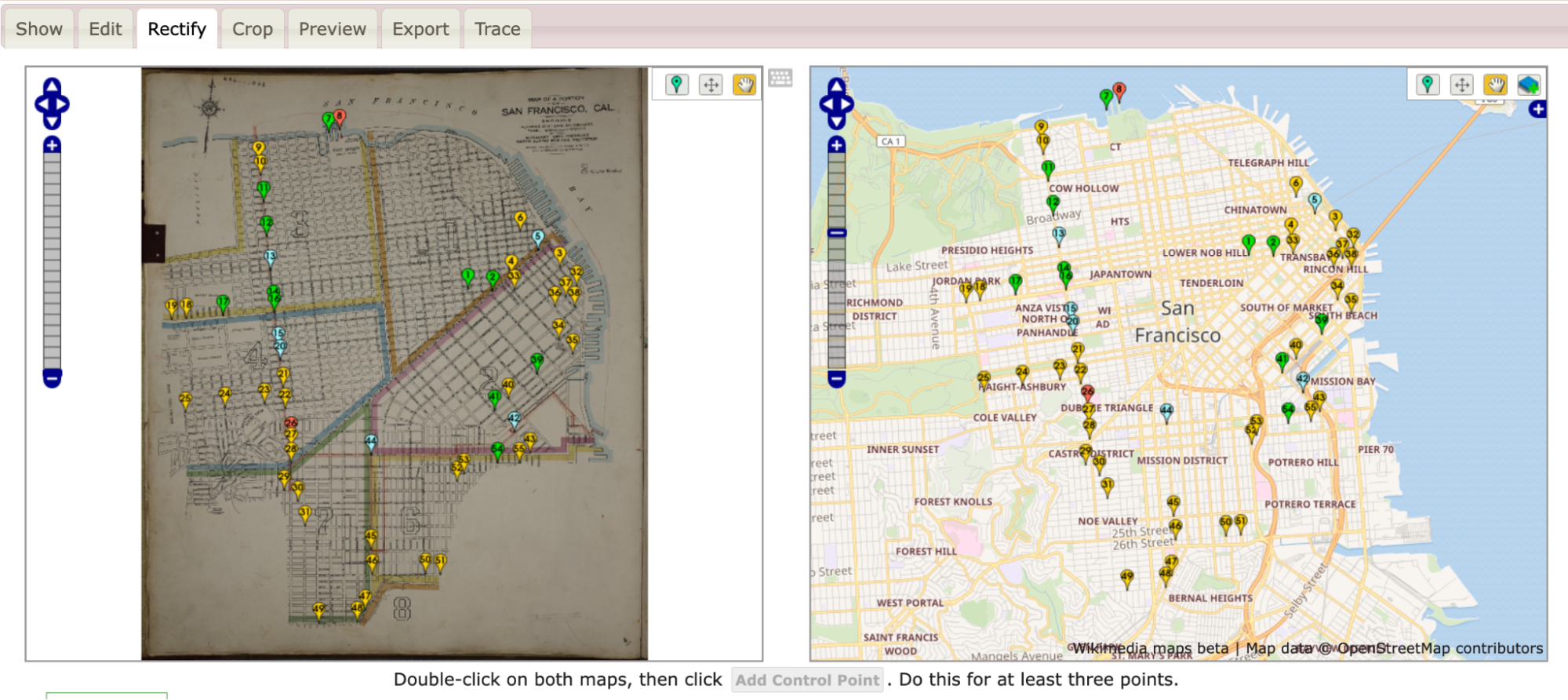

All said, I ended up with more than 40 pins (i.e., control points). As I went, I warped the image every few pins in order to save it and see where the image needed alignment.

As I added control points and warped my map, the pins shifted colors between greens, yellows, and reds with the occasional blue. The colors each demonstrated where the two maps were in exact alignment and where they were being pinched and, well, warped, to match.

Loading the warped map into ArcGIS Online as a layer

Once I was happy with the Sanborn image rectified against the OpenStreetMap that Wikimaps draws in, I was ready to export my work.

In this instance, I eventfully want to have two historic maps for layers and two sets of publisher data (1910s and 1950s).

To work with multiple layers, I needed to move away from Google My Maps and toward a more complex GIS program. Because UC Berkeley has a subscription to ArcGIS Online, I headed there. If I hadn’t had access to that online program, I’d have gone to QGIS. For an access point to ArcGIS online or for more on tools and access points, head to the UC Berkeley Library Research Guide for GIS (https://guides.lib.berkeley.edu/gis/tools).

I’d already set up my ArcGIS Online (AGOL) account, so I jumped straight in at https://cal.maps.arcgis.com/ and then clicked on the “Map” button in the upper-left navigation bar.

On the Map screen, ArcGIS defaulted to a map of the United States in a Mercator projection. ArcGIS also had the “Layers” options opened in the left-hand tool bars.

Because I didn’t yet have any layers except for my basemap, ArcGIS’s only option in “Layers” was “Add.”

Clicking on the down arrow to the right of “Add,” I selected “Add layer from URL.”

In response, ArcGIS Online gave me a popup box with a space for a URL.

I flipped back to my Wikimaps screen and copied the “Tiles (Google/OSM scheme),” which in this case read https://warper.wmflabs.org/maps/tile/7258/{z}/{x}/{y}.png.

Flipping back to ArcGIS Online, I pasted the tile link into the URL text box and made sure that the auto-populating “Type” information about the layer was accurate. I then hit a series of next to assure ArcGIS Online that I really did want to use this map.

Warning: Because I used a link, the resulting layer is drawn from Wikimaps every time I load my ArcGIS project. That does mean that if I had a poor internet connection, the map might take a hot minute to load or fail entirely. On UC Berkeley campus, that likely won’t be too much of an issue. Elsewhere, it might be.

Once my image layer loaded, I made sure I was aligned with San Francisco, and I saved my map with a relevant title. Good practice means that I also include a map description with the citation information to the Sanborn map layer so that viewers will know where my information is coming from.

Once I’ve saved it, I can mess with share settings and begin offering colleagues and other publics the opportunity to see the lovely, rectified Sanborn map. I can also move toward adding additional layers.

Next Time

Next post, I plan to write about how I’m going to add my lovely 1955 publisher dataset on top of a totally different, 1950 San Francisco map as a new layer. Yay!