Tag: Jewish history

Never Forget? UC Berkeley’s Oral History Center documents memories of the Holocaust for researchers and the public

“It’s too late now because there’s nobody I can ask.”

— Katalin Pecsi, child of Auschwitz survivor

The 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz is on January 27 of this year and 41% of Americans don’t know what Auschwitz is — including a whopping two-thirds of millennials. A recent survey found a stunning lack of basic knowledge in the United States about the Holocaust — defined by the US Holocaust museum as “the systematic, state-sponsored persecution and murder of six million Jews” that decimated the Jewish population in Europe. Almost one million Jews were killed in Auschwitz alone, the largest and most infamous of the death camps. With fewer and fewer Jews who experienced the Holocaust first-hand alive to tell their stories — the youngest survivors with memories of the camps are in their eighties and nineties today — the cry of Holocaust remembrance not to forget depends on a clear historical record.

Throughout the Oral History Center’s vast collection of interviews are more than 200 that reference the Holocaust. While there is no specific Oral History Center (OHC) project dedicated to documenting the Holocaust, interviews can be found within projects about food and wine, arts and letters, industry and labor, philanthropy, and more. Furthermore, our oral history collections about the history of UC Berkeley include memories of the Holocaust and its impact, including projects about the Free Speech Movement, the student political party SLATE, and faculty interviews. These oral histories document memories of the Holocaust from a multiplicity of perspectives, from the first-hand experiences of Jewish refugees who fled from Europe before it was too late, to Americans who first heard about the atrocities after the liberation of the camps. The Jewish narrators in particular talk about how the Holocaust was the driving factor in their careers, philanthropy, Israel advocacy, and political activism. These oral histories may be particularly interesting to scholars as they provide a different lens for looking at the Holocaust, capturing the histories of those who were being interviewed for other reasons, but nonetheless spoke about the impact of the Holocaust on their lives.

There are oral histories in the collection that preserve the experiences of Jewish refugees who managed to flee Europe before it was too late and build new lives for themselves in the United States. Alfred Fromm fled Germany for the US in 1936 and went on to build a successful wine distribution business; he became a philanthropist supporting numerous educational, cultural, and Jewish organizations, including UC Berkeley’s Magnes Museum. In 1939, violinist Sandor Salgo had a sponsor in the United States but was denied a visa from the US consul in Hungary, who said the Hungarian quota was filled until 1984. In tears, Salgo told a patroness that he would probably die in a concentration camp and she was able to intervene on his behalf; his brother died in Auschwitz. Berkeley Mechanical Engineering professor and dean George Leitmann escaped Nazi-occupied Austria in 1940 at the age of 15, a few years later to return to Europe during WWII as a US Army combat engineer. He was in the second wave of soldiers who liberated Landsberg Concentration Camp, and later served as a translator during the Nuremberg War Crime Trials. All these experiences influenced his scientific area of study in control theory — measuring risk, probability, and how to avoid catastrophe.

“We certainly got there in time to see the smoldering bodies they were trying to burn and the skeletons. That probably hit me more than it hit the rest of the guys, because here my father was still missing. I still had hopes to see him among the DPs [displaced persons].” — George Leitmann on the liberation of Landsberg concentration camp. His father did not survive.

The one collection of interviews that addresses the Holocaust in the most detail is that of the the San Francisco Jewish Community Federation Leadership. Here can be found the oral history of William Lowenberg, a Holocaust survivor, number 145382 of the Auschwitz-Birkenau killing complex. His interview details how as a teenager luck, good health, and his own survival strategies enabled him to survive his harrowing journey through extermination camps, the Warsaw Ghetto aftermath, and a death march, until he was liberated from Dachau concentration camp at the age of 18. After an attempt to go home (like so many, his house had been taken over), Lowenberg eventually settled in San Francisco, where the Jewish Family Services Agency helped him secure a job collecting rent for a realty company. He went on to become a major figure in industrial real estate in the city. Lowenberg gave back to the agency later, serving on the same committee that helped him, in the 1970s finding jobs for Jewish refugees from the Soviet Union. Of his life dedicated to philanthropic and political activism on behalf of the Jewish community and Israel, Lowenberg reflected, “I feel that Jewish survival depends on the Jews.”

“I was young, healthy, and I kept clean. I kept as clean as I could all of the time.” — William Lowenberg on his survival strategies

The OHC collection also includes interviews of those who were present for the liberation, like Berkeley History Professor Emeritus Richard Herr, who was serving in the Signal Intelligence Corps and visited Buchenwald shortly after the liberation. He describes the displaced persons wandering the streets, survivors in their striped pajamas, the pile of dead bodies. “I was told they’d died after the liberation. They’d just been in such poor shape. They were just skin and bones. It was terrible.”

The collection also includes interviews of those who didn’t directly experience the Holocaust, but heard about it through family, friends, teachers, even work acquaintances. Oral histories are unique in that they can include off-hand comments and asides that illuminate an era. Six million — two thirds of Europe’s Jews perished — but three million survived and many dispersed to other countries including the United States. Narrators would encounter these survivors, the tales of depravity would sear in their memories, and the narrators would sometimes make offhand remarks. Other narrators provide more details about the many facets of the Holocaust — resistance and the underground, escapes, refugees and displaced persons, concentration camps, the murder of entire families — such as the oral histories of Laurette Goldberg, who taught music at UC Berkeley; Berkeley MBA Ronald Kaufman; wine writer Mike Weiss; winery manager Morris Katz; economist Lester Telser; poet Carl Rakosi, and Berkeley student activist Daniel Goldstine.

Among these are the oral histories of children of Holocaust survivors, including Berkeley History Professor Emerita Paula Fass, Paula Kornell, and Katalin Pecsi. All of them attributed their careers to their parents’ experiences. Growing up in Hungary, Katalin Pecsi knew her father had survived Auschwitz, her uncle Buchenwald, and her paternal grandmother Dachau; but had been told they were political prisoners because of their affiliation with the Communist Party. She later learned that she was Jewish, that her mother’s entire family had been killed in the Holocaust, and began to question what she had been told. “When I was a child I was told that they were political prisoners because they never told me that we were Jewish… but I’m not sure that’s true that they arrived as political prisoners. I don’t know, it’s too late now because there’s nobody I can ask.” Learning about her Jewish heritage combined with her longing to know about her own family propelled Pecsi into a career in Holocaust remembrance, becoming the director of education at the Budapest Holocaust Memorial Center.

“My parents were both survivors of the concentration camps. They had lost families. Not just their parents and siblings, but in fact, husbands, wives and children. They were married to other people, and my mother had a son who was taken from her when he was three. My father had four children who were all taken away and died in Auschwitz. One of the things that’s very, very clear is that I became a historian because of it. I became a historian because history was always around.” — Berkeley Professor Paula Fass

“What the concentration camp [Dachau] instilled in my father was just the beauty of life, and I think he helped to instill…was the beauty of a vineyard or of a vine growing, or beauty of your garden or the beauty of winemaking.” — Paula Kornell, winemaker

The OHC collection includes numerous oral histories that touch on narrators’ reactions to learning about the Holocaust. Interviewers for the Rosie the Riveter World War II Homefront Collection, for example, frequently asked narrators, who came from many walks of life, when did they first learn about the Holocaust and what was their reaction. Like Beatrice Rudney and Bud Figueroa, narrators interviewed for the Rosie the Riveter collection generally responded that they learned about the horrors of the genocide after the war, sometimes mentioning newsreels (films of piles of naked corpses, survivors of skin and bones). Other narrators, sitting for longer life-history interviews, addressed this issue when talking about their childhoods. Oral histories of Jewish narrators reveal more knowledge about what was happening during the war itself, particularly those whose families housed refugees, or who received letters from family with news of mass killings — 13 family members gone — or whose letters from family in Europe just stopped one day, such as former Dean of Berkeley Law School Jesse Choper, Professor Emeritus of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Howard Schachman, Laurette Goldberg, Lester Telser, as well as Quaker activist Gerda Isenberg. Schachman observed, “I was certainly aware of what was going on to the Jews in Europe…. I doubted those people who claimed they weren’t aware of the Holocaust — it wasn’t called the Holocaust then.”

“I understood it during the war. There were always leaks of information of what was happening. Some people would escape from the concentration camps and come back and tell it.” — Jesse Choper, Dean Emeritus of Berkeley Law

The oral histories provide researchers with information about the range of feelings people had when they learned about the atrocities in the camps. Many of these are short responses to a direct question, such as in the Rosie the Riveter collection. Daniel Levin recalled a “sickening feeling;” DeMaurice Moses described being “inured to savagery by that time;” and as David Dibble remembered it, “You have to sort of genuflect and say, true, it was the worst thing that ever happened. And it was.” Some narrators recalled how other people talked about the Holocaust, and these interactions were indelible moments for them. Berkeley alumna and student activist Susan Griffin recalled an incident about four years after the war where her fellow Girl Scout Brownie troop members were laughing, saying Heil Hitler, and making the Nazi salute. She recalled the driver pulled over, emotional, and scolded that they must never do so again; and her grandparents, whom she described as “passive anti-Semites,” explained to the six-year-old “what an evil man Hitler was.” Berkeley History Professor Emeritus Larry Levine recalled being “shocked” when he was an undergraduate five years after the war ended, and an English professor told the class, “Don’t let the Jews tell you they are the only ones who have suffered.”

Some of the oral histories provide a glimpse into how the Holocaust affected Jewish Americans in the Baby Boom generation, living in its shadow. Berkeley alumna and student activist Julianne Morris, Adrienne Asch, and Wayne Feinstein recall how the Holocaust was something they always knew about, part of the culture. As Feinstein put it, “The first twenty or thirty years after the Second World War I think the Jewish community was in shock. And I grew up in that environment.” He described the Holocaust as “the primary motivation” for his lifelong dedication to Jewish education, cultural programs, and support for Israel.

“You couldn’t be a Jew in post-Holocaust America without knowing about the Holocaust. I mean, you grew up, you knew about the Holocaust, you knew about Israel.” — Adrienne Asch, disability rights activist and professor of bioethics

Finally, at least a few oral histories describe how narrators reacted upon visiting death camps as tourists years, even decades, after the end of the war. Through visiting these camps in person, these narrators came face to face with the scope of the horrors. Berkeley Economics Professor Emeritus and past director of the Institute of Industrial Relations, Lloyd Ulman, along with Marty Morgenstern, past director of Berkeley’s Center for Labor Research and Education, were taken to Auschwitz on a work trip to Poland. Ulman recalls how Morgenstern went outside and “put his head between his legs. He thought he was going to throw up or faint.” Ulman recalls “terrible things like seeing a whole collection of false teeth” [taken from the dead for their gold fillings] and feeling the “horror” that General Eisenhower had felt upon seeing the camps. Annette Dobbs also lived through the war but the enormity of the Holocaust really hit her when she visited Mauthausen Concentration Camp outside of Vienna in 1971. Expressing the sentiment of many of the narrators who spoke about the Holocaust, she said, “That day I made my own personal commitment to spend the rest of my life to see that nothing like that would ever happen to my people again.”

January 27, the date of the liberation of Auschwitz, is International Holocaust Remembrance Day.

Find these and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.

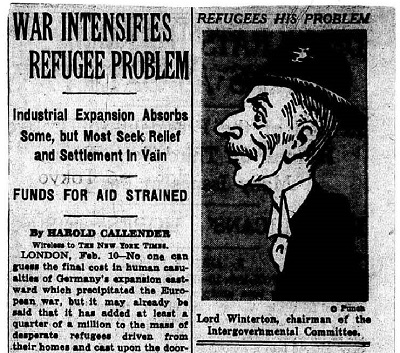

Primary Sources: Intergovernmental Committee on Refugees: The West’s Response to Jewish Emigration

From the publisher’s description: “The Intergovernmental Committee on Refugees (IGCR) was organized in London in August 1938 as a result of the Evian Conference of July 1938, which had been called by President Roosevelt to consider the problem of racial, religious, and political refugees from central Europe…. For the first time, there was discussion on extending protection to would-be refugees inside the country of potential departure, particularly central Europe. The IGCR, however, received little authority and almost no funds or support from its member nations for resettlement of refugees from Europe in countries allowing permanent immigration, and it had little success in opening countries to refugees…. In July 1944, 37 governments participated in the work of the Committee. Of these, representatives of nine countries, including the United States, served on its Executive Committee. The primary responsibility for determining the policy of the United States with regard to the Committee was that of the Department of State. It ceased to exist in 1947, and its functions and records were transferred to the International Refugee Organization of the United Nations.”

From the publisher’s description: “The Intergovernmental Committee on Refugees (IGCR) was organized in London in August 1938 as a result of the Evian Conference of July 1938, which had been called by President Roosevelt to consider the problem of racial, religious, and political refugees from central Europe…. For the first time, there was discussion on extending protection to would-be refugees inside the country of potential departure, particularly central Europe. The IGCR, however, received little authority and almost no funds or support from its member nations for resettlement of refugees from Europe in countries allowing permanent immigration, and it had little success in opening countries to refugees…. In July 1944, 37 governments participated in the work of the Committee. Of these, representatives of nine countries, including the United States, served on its Executive Committee. The primary responsibility for determining the policy of the United States with regard to the Committee was that of the Department of State. It ceased to exist in 1947, and its functions and records were transferred to the International Refugee Organization of the United Nations.”

The Library recently acquired the online archive of the Department of State’s records relating to the IGCR, which reside in the National Archives. More information about the scope and arrangement of the collection is available in the finding aid for the microfilmed edition.