Author: Roger Eardley-Pryor

Earth Day at 50: Memories from Sierra Club Oral Histories

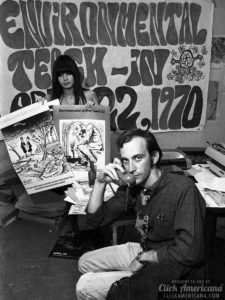

Earth Day turns 50 this month. A half-century ago, on April 22, 1970, environmental awareness and concern exploded in a nationwide outpouring of celebrations and protests during the world’s first Earth Day. That first Earth Day drew an estimated twenty million participants across the United States—roughly a tenth of the national population—with involvement from over ten thousand schools and two thousand colleges and universities. Earth Day on April 22, 1970, became the then-largest single-day public protest in U.S. history. The actual numbers of participants were even higher, as several universities, notably the University of Michigan, held massive Earth Day teach-ins during the weeks before April 22 to avoid overlapping with their final exams. From New York City to San Francisco, from Birmingham to Ann Arbor—millions of Americans gathered on campuses, met in classrooms, visited parks and public lands together, participated in local clean-ups, and marched in the streets for greater environmental awareness and to demand greater environmental protections. Even Wisconsin Senator Gaylord Nelson, who in the fall of 1969 promoted the idea for nation-wide Earth Day teach-ins, was surprised, calling the occasion a “truly astonishing grass-roots explosion.” And over the ensuing fifty-years since 1970, Earth Day events have spread globally to over 193 countries, making it the world’s largest secular holiday celebrated by more than a billion people each year.

But this April, despite years of planning for Earth Day’s fiftieth anniversary, the novel coronavirus—itself a world-wide environmental event—has disrupted Earth Day 2020 plans across the planet. While we cannot celebrate Earth Day’s golden anniversary as previously planned, we can commemorate it with recollections and lessons learned by those who attended and organized the first Earth Day events in 1970. The Oral History Center’s archives list over seventy interviews that mention Earth Day, according to the “Advanced Search” fields of our collection’s search engine. I’ve selected here a few memories of the first Earth Day from our Sierra Club Oral History Project, a longstanding collaboration between the Oral History Center and the Sierra Club, which itself originated shortly after the first Earth Day. These Earth Day memories shared by Sierra Club members begin with experiences in the streets of New York City, they include memories at the forefront of environmental law, and they conclude with events at the University of Michigan during the first-ever Earth Day teach-in.

But this April, despite years of planning for Earth Day’s fiftieth anniversary, the novel coronavirus—itself a world-wide environmental event—has disrupted Earth Day 2020 plans across the planet. While we cannot celebrate Earth Day’s golden anniversary as previously planned, we can commemorate it with recollections and lessons learned by those who attended and organized the first Earth Day events in 1970. The Oral History Center’s archives list over seventy interviews that mention Earth Day, according to the “Advanced Search” fields of our collection’s search engine. I’ve selected here a few memories of the first Earth Day from our Sierra Club Oral History Project, a longstanding collaboration between the Oral History Center and the Sierra Club, which itself originated shortly after the first Earth Day. These Earth Day memories shared by Sierra Club members begin with experiences in the streets of New York City, they include memories at the forefront of environmental law, and they conclude with events at the University of Michigan during the first-ever Earth Day teach-in.

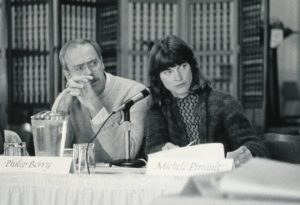

We begin with Michele Perrault, a future two-time president of the Sierra Club, who in 1970 lived and worked in New York City as an elementary science educator. New York City was the site the nation’s largest celebration of Earth Day, which garnered nationwide media attention given that NBC, CBS, ABC, The New York Times, Time, and Newsweek were all headquartered in Manhattan. Perrault, then twenty-eight years old, taught in the demonstration school at the Bank Street College of Education, founded in 1916 by Lucy Sprague Mitchell, a child education reformer and, earlier, Berkeley’s first Dean of Women. For her part, Perrault shared during her oral history how she organized “a Bank Street program out in the street for Earth Day in New York City.” Perrault recalled, “we had our own booth, and I had the kids there … Mostly we sang songs and danced around and had some visuals and books that people could read or get, and we had some pamphlets from the [Bank Street] college that talked about it.” In the process, Perrault and her students joined hundreds of thousands other Earth Day participants in the streets of Manhattan. John Lindsay, the Republican mayor of New York, had closed traffic on Fifth Avenue for Earth Day and made Central Park available for gigantic crowds to march and celebrate together. In Union Square, crowds of 20,000 people gathered at any given time, with the New York Times estimating over 100,000 people visiting Union Square throughout the day.

and Newsweek were all headquartered in Manhattan. Perrault, then twenty-eight years old, taught in the demonstration school at the Bank Street College of Education, founded in 1916 by Lucy Sprague Mitchell, a child education reformer and, earlier, Berkeley’s first Dean of Women. For her part, Perrault shared during her oral history how she organized “a Bank Street program out in the street for Earth Day in New York City.” Perrault recalled, “we had our own booth, and I had the kids there … Mostly we sang songs and danced around and had some visuals and books that people could read or get, and we had some pamphlets from the [Bank Street] college that talked about it.” In the process, Perrault and her students joined hundreds of thousands other Earth Day participants in the streets of Manhattan. John Lindsay, the Republican mayor of New York, had closed traffic on Fifth Avenue for Earth Day and made Central Park available for gigantic crowds to march and celebrate together. In Union Square, crowds of 20,000 people gathered at any given time, with the New York Times estimating over 100,000 people visiting Union Square throughout the day.

Earlier that month, at a meeting of student teachers involved in planning Earth Day teach-ins in New York, Perrault met René Dubos, famed microbiologist and Pulitzer-Prize-winning author credited with coining the phrase “Think Globally, Act Locally.” Perrault, in her role as education chair of the Sierra Club’s Atlantic Chapter, was then producing a monthly newsletter for environmental educators called Right Now, in which she  recalled what Dubos emphasized for Earth Day. Dubos had “stressed the importance and need for people to take time to reevaluate what is needed for quality of life, to sift and sort alternatives perhaps not in existence now, to look in a new way at what the future could be like, and then devise plans for making it so.” Perrault added that “We, as teachers, need to ask new questions about our own values, about our own social and economic systems and their relationship to the environment, so as to enrich the present and potential environment for children.” (Two copies of Right Now are included in the appendix to Perrault’s oral history.) Less than a year after Earth Day, Perrault then organized at Bank Street College an education conference on “Environment and Children” and invited Dubos as the keynote speaker. Perrault recalled Dubos calling for stimulating environments for children that offered “the ability to choose, to have variety, to not just be in one place where everything was static around them and where they weren’t in control. [He] had a big paper on this whole issue of free will and being able to make choices, and how the environment would influence them.” Years later, after moving to California, Perrault took her own children on annual backpacking trips deep into the High Sierra where they could run wild and free, stimulated by natural wilderness.

recalled what Dubos emphasized for Earth Day. Dubos had “stressed the importance and need for people to take time to reevaluate what is needed for quality of life, to sift and sort alternatives perhaps not in existence now, to look in a new way at what the future could be like, and then devise plans for making it so.” Perrault added that “We, as teachers, need to ask new questions about our own values, about our own social and economic systems and their relationship to the environment, so as to enrich the present and potential environment for children.” (Two copies of Right Now are included in the appendix to Perrault’s oral history.) Less than a year after Earth Day, Perrault then organized at Bank Street College an education conference on “Environment and Children” and invited Dubos as the keynote speaker. Perrault recalled Dubos calling for stimulating environments for children that offered “the ability to choose, to have variety, to not just be in one place where everything was static around them and where they weren’t in control. [He] had a big paper on this whole issue of free will and being able to make choices, and how the environment would influence them.” Years later, after moving to California, Perrault took her own children on annual backpacking trips deep into the High Sierra where they could run wild and free, stimulated by natural wilderness.

Perrault was recruited to the Sierra Club shortly before Earth Day by David Sive, a pioneer of environmental law in New York, whose children Perrault taught in her science classroom. Another Sierra Club member and trailblazer of environmental law, James Moorman, shared his own memories of the first Earth Day in his oral history. By 1970, Moorman had joined the recently created Center for Law and Social Policy in Washington, DC, an influential public-interest law firm. As a young trial lawyer in the late 1960s, Moorman brought two cases that became landmarks in environmental law, including a petition to the Department of Agriculture to de-register the pesticide DDT, as well as a suit challenging construction of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline. For the pipeline case, Moorman pioneered use of the National  Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), enacted in January 1970, to demand from the Department of Interior a detailed environmental impact statement for the construction project. Moorman recalled how “the preliminary injunction hearing for the Trans-Alaska Pipeline was originally set for Earth Day. The hearing got postponed. It didn’t occur for another two weeks. But when the judge first set the hearing, I said, ‘Holy cow! He set the hearing for this on Earth Day and he doesn’t know it, and the oil companies don’t know it. I’m going to get to make my argument on Earth Day. That’s fantastic!’ But then there was a postponement, and the argument didn’t occur until two weeks later. But it was wonderful anyway.” Moorman won his case, but Congress directly intervened to approve the pipeline by law. Nonetheless, Moorman’s injunction forced the oil companies to spend three more years and a small fortune on engineering, analysis, and documentation. The final environmental impact statement for the Trans-Alaska Pipeline stretched to nine volumes. Moorman’s intervention helped produce a safer pipeline that is still considered a wonder of engineering.

Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), enacted in January 1970, to demand from the Department of Interior a detailed environmental impact statement for the construction project. Moorman recalled how “the preliminary injunction hearing for the Trans-Alaska Pipeline was originally set for Earth Day. The hearing got postponed. It didn’t occur for another two weeks. But when the judge first set the hearing, I said, ‘Holy cow! He set the hearing for this on Earth Day and he doesn’t know it, and the oil companies don’t know it. I’m going to get to make my argument on Earth Day. That’s fantastic!’ But then there was a postponement, and the argument didn’t occur until two weeks later. But it was wonderful anyway.” Moorman won his case, but Congress directly intervened to approve the pipeline by law. Nonetheless, Moorman’s injunction forced the oil companies to spend three more years and a small fortune on engineering, analysis, and documentation. The final environmental impact statement for the Trans-Alaska Pipeline stretched to nine volumes. Moorman’s intervention helped produce a safer pipeline that is still considered a wonder of engineering.

In the year following the first Earth Day, Moorman accepted a new job as the founding Executive Director of the Sierra Club Legal Defense Fund (SCLDF), now called Earthjustice, one of the nation’s earliest and most influential public-interest environmental law organizations. Moorman directed SCLDF through 1974 and he worked as a staff attorney with the organization through 1977, after which he became Assistant Attorney General for Land and Natural Resources during President Carter’s administration. In his 1984 oral history, Moorman reflected on the importance of Earth Day for environmental law: “The fact is Earth Day came rather early in all this [environmental law] movement. We’ve been living on the energy created by Earth Day ever since.” Mike McCloskey agreed.

In 1970, Mike McCloskey, also a lawyer, was still new in his role as Executive Director of the Sierra Club, a position he held through 1985. In his first of two oral histories, this one from 1981, McCloskey recalled the Earth-Day-era as  “a very exciting time in terms of developing new theories [of environmental law], and our spirits were charged up. The courts were anxious to make law in the field of the environment. There were judges who were reading, and they were stimulated by the prospect. They were eager to get environmental cases.” McCloskey continued, “what became clear over the next few years [after Earth Day] were that dozens of, if not hundreds, of laws were passed and agencies brought into existence.” Indeed, in the months and years following the first Earth Day, President Nixon established the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and Congress passed a suite of landmark environmental statutes—including an amended Clean Air Act; the Clean Water Act; the Safe Drinking Water Act; the Endangered Species Act; the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA); the Toxic Substances and Control Act (TSCA) and many others—all of which have, thus far, avoided extinction.

“a very exciting time in terms of developing new theories [of environmental law], and our spirits were charged up. The courts were anxious to make law in the field of the environment. There were judges who were reading, and they were stimulated by the prospect. They were eager to get environmental cases.” McCloskey continued, “what became clear over the next few years [after Earth Day] were that dozens of, if not hundreds, of laws were passed and agencies brought into existence.” Indeed, in the months and years following the first Earth Day, President Nixon established the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and Congress passed a suite of landmark environmental statutes—including an amended Clean Air Act; the Clean Water Act; the Safe Drinking Water Act; the Endangered Species Act; the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA); the Toxic Substances and Control Act (TSCA) and many others—all of which have, thus far, avoided extinction.

McCloskey described Earth Day 1970 as an explosion of environmental consciousness that had grown steadily throughout the late 1960s. In 1968, fellow conservationists thought the best of things has already happened with the creation of Redwood National Park in California, North Cascades National Park in Washington state, and passage of both the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act and the National Trails System Act, all in that year. McCloskey recalled, “We at the moment thought this was some high point in conservation history and wondered whether much would happen thereafter.” When President Nixon came into office in January 1969, McCloskey and other Sierra Club leaders “felt very defensive and threatened, not realizing that we were on a threshold of an explosion into a period of our greatest growth and influence.” Instead of a plateau or even a decline in environmental efforts, McCloskey and fellow Sierra Club leaders saw the American environmental movement  experience a “tremendous take-off in terms of the overall quantity of activity, enthusiasm, and support with Earth Day coming. … it was just an eruption of activity on every front.” But much to his surprise, with Earth Day in 1970, McCloskey also saw how many traditional leaders of the conservation movement were quickly “regarded as old hat and out of step with the times.” In their place, he witnessed how “people emerged at the student level, literally from nowhere, who were inventing new standards for what was right and what should be done and whole new theories overnight. For instance, I remember hostesses who were suddenly saying, ‘I can’t serve paper napkins anymore. I’ve got to have cloth napkins.’ Someone had written that paper napkins were terribly wrong, and colored toilet paper was regarded as a sin. But all sorts of people from different backgrounds coalesced in the environmental movement. People who were interested in public health suddenly emerged and very strongly.” One such person was Doris Cellarius.

experience a “tremendous take-off in terms of the overall quantity of activity, enthusiasm, and support with Earth Day coming. … it was just an eruption of activity on every front.” But much to his surprise, with Earth Day in 1970, McCloskey also saw how many traditional leaders of the conservation movement were quickly “regarded as old hat and out of step with the times.” In their place, he witnessed how “people emerged at the student level, literally from nowhere, who were inventing new standards for what was right and what should be done and whole new theories overnight. For instance, I remember hostesses who were suddenly saying, ‘I can’t serve paper napkins anymore. I’ve got to have cloth napkins.’ Someone had written that paper napkins were terribly wrong, and colored toilet paper was regarded as a sin. But all sorts of people from different backgrounds coalesced in the environmental movement. People who were interested in public health suddenly emerged and very strongly.” One such person was Doris Cellarius.

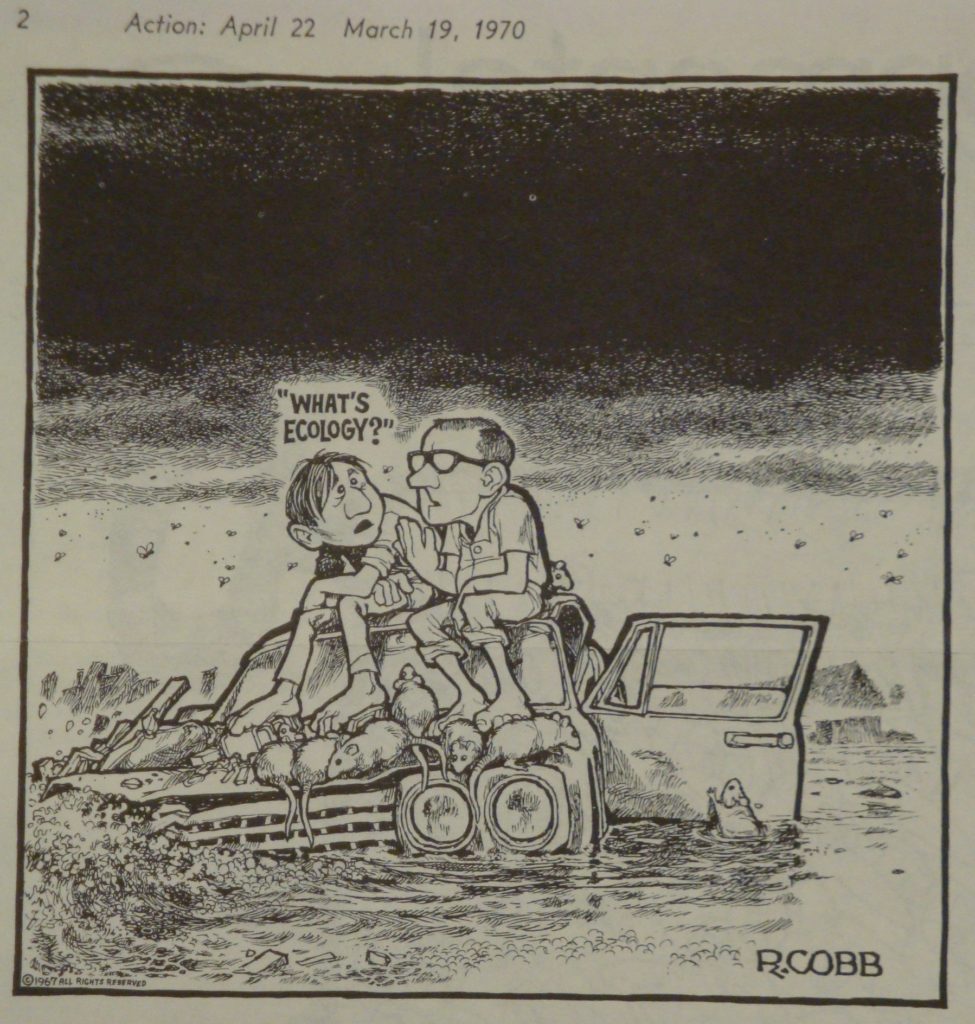

In 1970, Doris Cellarius lived in Ann Arbor, Michigan, with her children and husband, Richard (Dick) Cellarius, a professor of botany then teaching at the University of Michigan. According to Doris, she and Dick were both members of the Sierra Club in 1970, but mostly for hiking and social engagement, less for activism. The extraordinary events surrounding Earth Day in Ann Arbor changed everything. Doris explained, “Earth  Day came as a great shock to me because it had never occurred to me that the environment didn’t clean itself. I thought that water that flows along in a creek was purified by sunlight, and I guess I didn’t know a lot about where pollution came from. When I learned at the time of Earth Day how much pollution there was and how bad pesticides were, I instantly became very active in the pollution area of the environment.” In the wake of Earth Day, Doris Cellarius drew upon her master’s degree in biology from Columbia University to become a grassroots activist and environmental organizer, particularly against the use of pesticides and other toxic chemicals. Within the Sierra Club, she became head of several local and national committees focused on empowering people in campaigns for hazardous waste clean-up and solid waste management. In her oral history, Doris Cellarius reflected on the impetus behind her decades of environmental activism: “I learned at Earth Day there was pollution, so I think, having learned there was pollution, I decided that people should find out ways to stop creating that pollution.”

Day came as a great shock to me because it had never occurred to me that the environment didn’t clean itself. I thought that water that flows along in a creek was purified by sunlight, and I guess I didn’t know a lot about where pollution came from. When I learned at the time of Earth Day how much pollution there was and how bad pesticides were, I instantly became very active in the pollution area of the environment.” In the wake of Earth Day, Doris Cellarius drew upon her master’s degree in biology from Columbia University to become a grassroots activist and environmental organizer, particularly against the use of pesticides and other toxic chemicals. Within the Sierra Club, she became head of several local and national committees focused on empowering people in campaigns for hazardous waste clean-up and solid waste management. In her oral history, Doris Cellarius reflected on the impetus behind her decades of environmental activism: “I learned at Earth Day there was pollution, so I think, having learned there was pollution, I decided that people should find out ways to stop creating that pollution.”

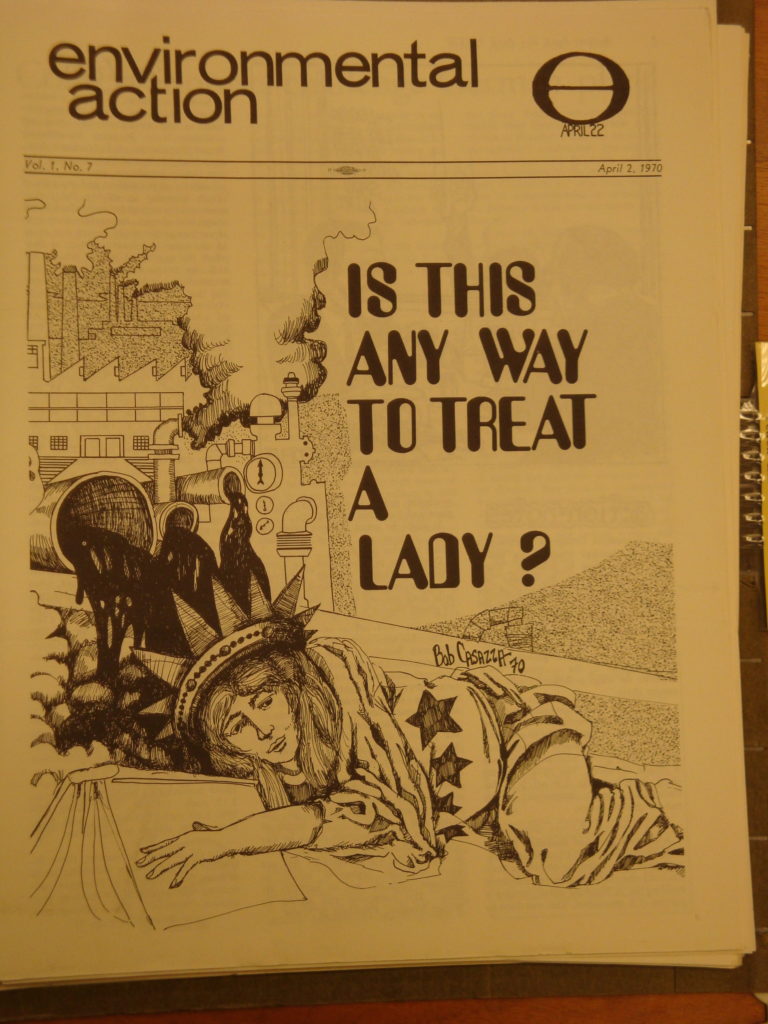

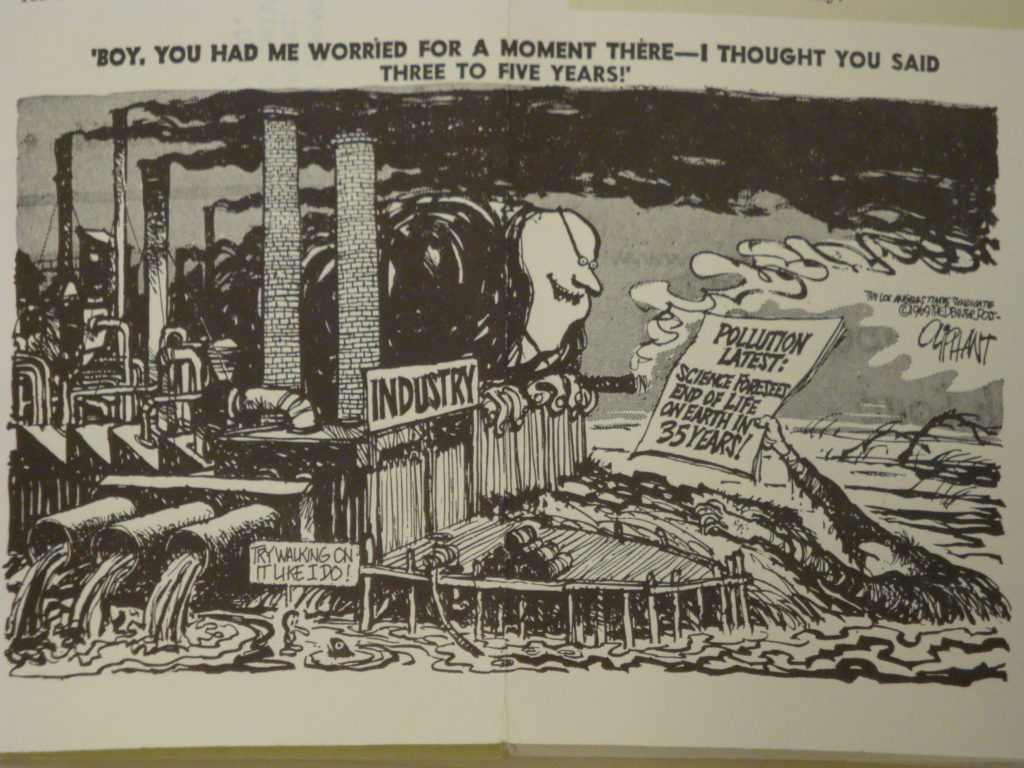

Fifty years ago, the dynamic events surrounding the first Earth Day reflected how environmental issues could rapidly mobilize new publics for radical reform and institutional action. Indeed, the small organization created to nationally coordinate the first Earth Day took the name Environmental Action. Denis Hayes, the then-twenty-five-year-old national coordinator for Environmental Action, announced on Earth Day, “We are building a movement … a movement that values people more than technology, people more than political boundaries and political ideologies, people more than profit.” This exuberance for a new kind of environmental movement, according to historian John McNeill, arose “in a context of countercultural critique of any and all established orthodoxies.” But, at its root, Earth Day—and the concomitant flowering of concern for Spaceship Earth and all travelers on it—constituted “a complaint against economic orthodoxy.” According to McNeil, “It was a critique of the faith of economists and engineers, and their programs to improve life on earth.” For new adherents to this ecological insight, the popularity of Earth Day’s events contributed collectively to “a general sense that things were out of whack and business as usual was responsible.” That all sounds terribly familiar today.

than political boundaries and political ideologies, people more than profit.” This exuberance for a new kind of environmental movement, according to historian John McNeill, arose “in a context of countercultural critique of any and all established orthodoxies.” But, at its root, Earth Day—and the concomitant flowering of concern for Spaceship Earth and all travelers on it—constituted “a complaint against economic orthodoxy.” According to McNeil, “It was a critique of the faith of economists and engineers, and their programs to improve life on earth.” For new adherents to this ecological insight, the popularity of Earth Day’s events contributed collectively to “a general sense that things were out of whack and business as usual was responsible.” That all sounds terribly familiar today.

This year, on the golden anniversary of Earth Day, life all across the planet is out of whack and business as usual has come to a sudden stop. From climate change to the novel coronavirus to the deteriorating condition of American politics, a slew of increasingly complex and interconnected problems affect us all. But perhaps, this moment—like the one in 1970—offers a unique opportunity to think how we might begin things anew. Perhaps, as René Dubos advised on the first Earth Day in April 1970, we in 2020 can “take time to reevaluate what is needed for quality of life, to sift and sort alternatives … to look in a new way at what the future could be like, and then devise plans for making it so.” May it be so. May you help make it so.

Michele Perrault: Sierra Club President 1984-1986 and 1993-1994, Environmental Educator, and Nature Protector

Michele Perrault – new Sierra Club oral history release

Michele Perrault twice served as national president of the Sierra Club, from 1984-1986 and from 1993-1994. She became the first female president of the Sierra Club in the modern era, since it became a nation-wide and then international organization with a multi-million-dollar operating budget. Environmental education, protecting nature, and extensive networking emerged as key themes in Perrault’s life as an environmental activist and leader. Perrault’s oral history is the first interview in the renewed Sierra Club Oral History Project—a long-standing collaboration between the Sierra Club and the Oral History Center at UC Berkeley that has, over the prior half century, preserved the Sierra Club’s past through oral history interviews.

Perrault was born in the Bronx, New York on May 8, 1941. She attended the High School of Music & Art in New York City, depicted later in the television series Fame. After a stint as one of the first women to attend the SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry, Perrault received her B.A. from Hunter College. Perrault’s Sierra Club activism began in the late 1960s when she was recruited to the Club’s Atlantic chapter by pioneering environmental lawyer, David Sive, whose children Perrault taught in her science classroom. Perrault quickly became chair of the chapter’s education committee and initiated a newsletter to communicate environmental information and share opportunities for activism, a practice she would replicate years later as International Vice President of the Sierra Club. Copies of Right Now, Perrault’s environmental education newsletter for the Club’s Atlantic Chapter, as well as a copy of her later International Activist, the online newsletter of the national Sierra Club’s International Committee, appear in an appendix to her oral history.

Perrault volunteered with the Sierra Club for many decades at every level, including as chair of various local, regional, and national committees. With her acute intelligence, deep curiosity, and exuberant energy, she honed expertise in a wide variety of issues: from off-shore drilling to solid waste treatment; from corporate fundraising to political lobbying; from the endangered tigers of India to the protection of wild places in Antarctica. In the 1970s, Perrault lead campaigns in Massachusetts against off-shore drilling and its on-shore effects, at one point garnering publicity for hanging dead fish from the window of the campaign’s headquarters. Perrault met fellow Sierra Club leader Phillip Berry at a national Sierra Club council meeting and, in 1978, moved to California where they were married. Beginning in 1981, Perrault won multiple elections to the Club’s national board of directors on which she served through 2001, including her two terms as Sierra Club president. Perrault also served as a board member of Earth Team, Green Seal, and Greenbelt Alliance. Her lifetime of environmental activism includes three U.S. Citizen Advisory Commissions under three different U.S. presidents, as well as appointment by the U.S. Department of State as a delegate to several Arctic Treaty Consultative Meetings in locations around the world.

Perrault’s oral history is the newest addition to the Sierra Club Oral History Project, an enduring partnership between the Sierra Club and the Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library. Initiated in 1970, amid an upsurge of environmental activism that produced the first Earth Day and codified a suite of new legal statutes, the Sierra Club Oral History Project now includes accounts from over one hundred volunteer leaders and staff members active in the Club for more than a century. Varying from only one hour to over thirty hours in length, these interviews highlight the breadth, depth, and significance of eclectic environmental efforts in both the national Sierra Club and the Club’s grassroots at regional and chapter levels—from education to litigation to legislative lobbying; from wilderness preservation to energy policy to environmental justice; from outdoor adventures to climate change activism to controlling chemicals; from California to the Carolinas to Alaska and beyond to international realms.

Together with the sizable archive of Sierra Club papers and photographs also in The Bancroft Library, the Sierra Club Oral History Project offers an extraordinary lens on the evolution of environmental issues and activism over the past century, as well as the motivations, conflicts, and triumphs of individuals who helped direct that evolution. The full-text transcripts of all interviews in the Sierra Club Oral History Project, including this interview with Michele Perrault, can be found online via the Oral History Center website.

The Oral History Center extends great thanks to all narrators who, since the early 1970s, shared their precious memories in the Sierra Club Oral History Project. We also thank the Sierra Club board of directors for recognizing early on the long-term importance of preserving the Club’s history and its evolution; to the past members of the Sierra Club’s History Committee, especially its founding chair Marshall Kuhn; to special donors who provided funding for individual Sierra Club oral history interviews; and to the trustees of the Sierra Club Foundation for providing the necessary funding to initiate, expand, and more recently renew this oral history project. Much appreciation goes to staff members of the Sierra Club and the Sierra Club Foundation who helped make these oral histories possible, most recently and notably to Therese Dunn, librarian of the William E. Colby Memorial Library at the Sierra Club’s headquarters in Oakland. Special thanks, too, to all prior oral history interviewers, most importantly to Ann Lage for her more than three decades of exceptional work on this project.

I am grateful and excited to conduct new oral histories with leaders of the Sierra Club, one of the most significant environmental organizations in history. And I deeply appreciate the narrators, like Michele Perrault, who welcome me into their homes, who set aside significant time to conduct these oral histories, and who, in the process, share their meaningful memories of protecting the planet for all of us to explore and enjoy.

Roger Eardley-Pryor, Ph.D.

Historian and Interviewer, Sierra Club Oral History Project

Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library

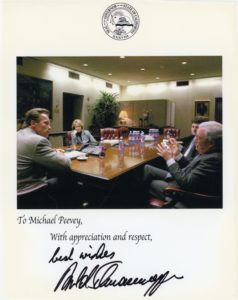

Michael R. Peevey: An Entrepreneur in Business, Energy, Labor, and Politics

New Transcript Release: Michael R. Peevey

A key theme throughout Michael R. Peevey’s life, which he narrates in this extensive oral history, has been establishing a balance between economic dynamism and environmental harmony.

In the 2000s, as President of the California Public Utilities Commission and lead regulator of California’s vast energy industry, Peevey combated climate change with policies that incentivized the state’s transition to renewable energy. In the late 1990s, his own incredibly successful start-up company, New Energy Ventures, offered such efficiencies in electricity use and cost that it secured contracts from major companies and organizations, including all US military installations across California. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, while president of the Southern California Edison utility company, Peevey spearheaded efforts for electric vehicles. And in the 1970s, Peevey balanced economy and environment by co-founding and directing a new political advocacy organization called the California Council on Environment and Economic Balance (CCEEB), made up of labor organizations, powerful corporations, and environmentalists.

Michael R. Peevey was born in New York City in 1938 and moved to San Francisco in 1944. After earning his Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees in Labor Economics from the University of California, Berkeley in 1959 and 1961, respectively, Peevey helped pioneer President John F. Kennedy’s New Frontier at the US Department of Labor. Peevey returned to California in 1963 to become research director of the California Labor Federation.

In 1973, shortly after creation of the California Coastal Commission, Peevey co-founded and became executive director of the California Council on Environment and Economic Balance (CCEEB), which was chaired by former California Governor Pat Brown. Peevey later helped establish similar institutions to balance environmental improvement with economic opportunity, including the California Foundation for Environment and Economy (CFEE), CALSTART, the Pacific Forest and Watershed Lands Stewardship Council, and the California Clean Energy Fund.

Peevey became deeply involved in California’s energy sectors. In 1984, Peevey joined the Southern California Edison utility company, where he quickly rose to become president of both Edison International and Southern California Edison before departing in 1993. In 1995, amid deregulation of California’s energy economy, Peevey co-founded New Energy Ventures (now NewEnergy, Inc.), which rapidly rose from zero to $600 million in annual sales. Peevey and his co-founders sold New Energy to AES in 1999.

In 2001, amid skyrocketing electricity costs and rolling brown-outs, Governor Grey Davis requested Peevey come to Sacramento to help mitigate the California energy crisis. In 2002, after Peevey helped control the crisis, Governor Davis appointed him as president of the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC). Both ensuing California Governors Arnold Schwarzenegger and Jerry Brown reappointed Peevey as CPUC president before Peevey’s retirement in late 2014. In 2017, Peevey co-authored the book California Goes Green: A Roadmap to Climate Leadership, which further details ways that California has pioneered paths toward environmental sustainability while maintaining its astounding economic dynamism.

In this oral history, Peevey discusses all the above events, as well as the following topics: his family background and upbringing; education at UC Berkeley; work in labor organizations; running for elected office; political advocacy on environmental issues; reflections on political and executive leadership; his career at Southern California Edison; market deregulation and entrepreneurship; the California energy crisis in the early 2000s; leadership of the California Public Utilities Commission; and policies he championed to incentivize California’s green-energy economy.

From the Archives: Women in the Sierra Club

“Female Consciousness and Environmental Care”

(Undergraduate Research Apprentice Program, Spring 2019)

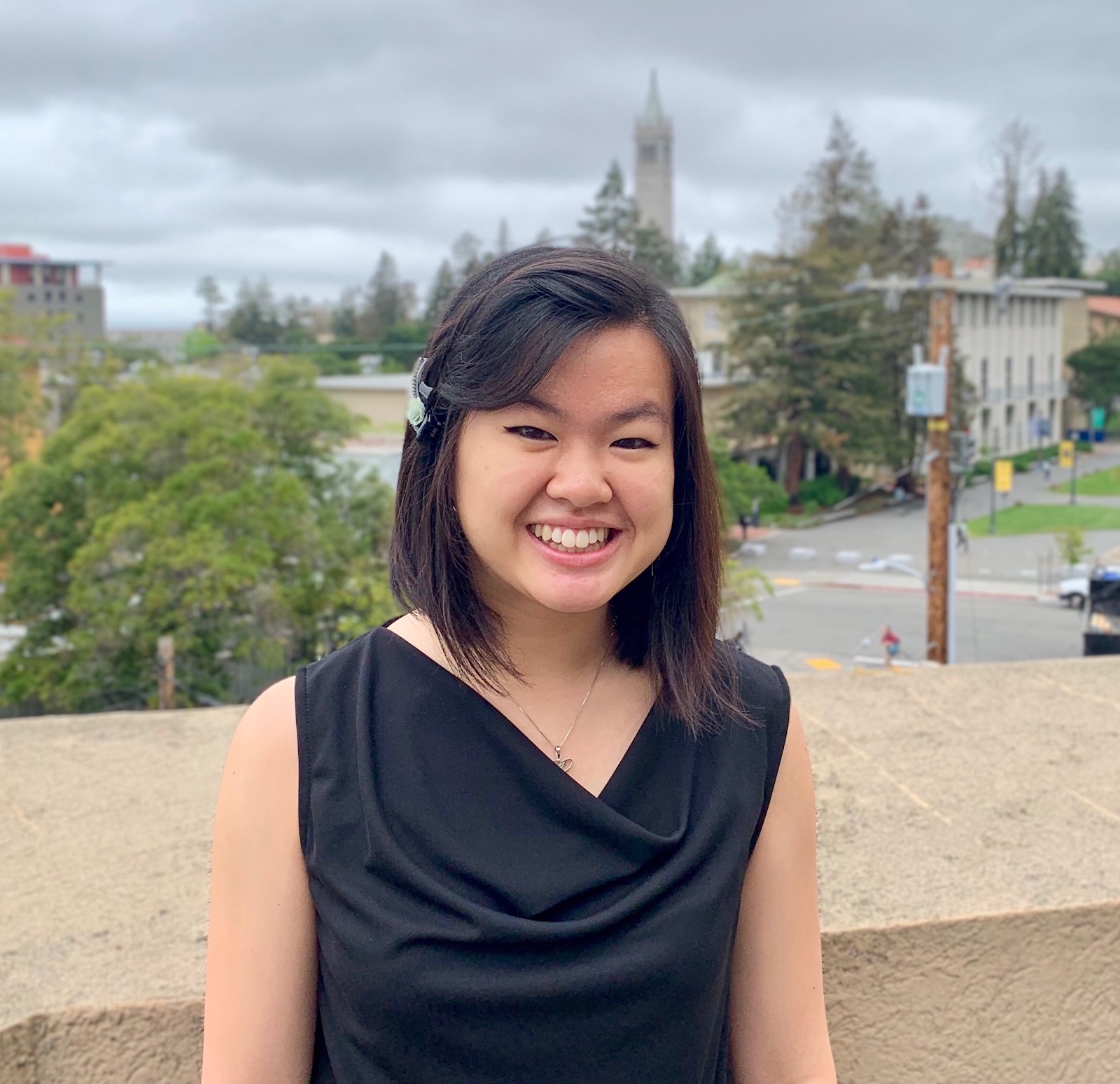

By Ella Griffith

Ella Griffith is a rising senior at UC Berkeley majoring in Environmental Science, Policy, & Management (ESPM) within the College of Natural Resources. In the Spring 2019 semester, Ella worked with historian Roger Eardley-Pryor of the Oral History Center and earned academic credits as part of UC Berkeley’s Undergraduate Research Apprentice Program (URAP). URAP provides opportunities for undergraduates to work closely with Berkeley scholars on the cutting edge research projects for which Berkeley is world-renowned. Ella’s research projects included analysis of the Oral History Center’s exceptional archive of interviews with Sierra Club members, which resulted in this month’s “From the Archives” article.

The work of the Sierra Club has, over time, evolved beyond outdoor exploration and advocacy for natural spaces to make marginalized identities central in its efforts. For my Undergraduate Research Apprenticeship Program (URAP) project in Spring 2019, I began looking for historical narratives about environmental justice in the Oral History Center’s interviews with Sierra Club members. As one of the oldest and largest conservation organizations in the United States, the Club has been scrutinized historically for its elite membership and prior lack of intersectional awareness around environmental issues. I determined, however, that the Club’s evolution toward holistic inclusivity—environmental and social—can be credited largely to the fierce, wonderful women who played, and continue to play, a role in shaping the Club’s future. As such, the nuanced roles and perspectives of women in the Sierra Club emerged as the captivating focus in my URAP research.

As a young woman and fellow environmental activist, I cherished reading other women’s personal and environmental perspectives, especially on the challenges they faced and the empowerment they experienced through their work within the Sierra Club. The themes and issues that the women spoke on remain relevant to today’s gendered issues. Their narratives built upon one another, and in the end, I could not escape feeling that what remains, in the present, is me. Women today expand on the layers of work that earlier women set down before us. Women activists—environmental and otherwise—stand now where we are because earlier women were not satisfied with where they were. But the process of change remains slow. Through these oral history interviews, we can learn more about the work that has been done, to help us understand what is left to do. As a result, the Sierra Club’s developing scope of work on equity, and the narrative of its adaptation, is important in understanding inclusivity in the greater environmental field.

In the Sierra Club’s oral history collection, I found generations of women’s stories. These archived interviews with women reflect a development of female consciousness threaded through the common denominator of love and care for the environment. As I read more interviews, vibrant patterns emerged. Women in the Sierra Club spoke similarly on the themes of fierce activism rooted in family values, of nature as an equalizer, and about the role of women in leadership positions within the Club. Other recurring motifs were less empowering, such as inequality in resources, the cult of domesticity demarcating women’s roles in the Club, and perhaps a more abstract trend of women’s apparent value as interviewees because of their proximity to prominent men in the Club. But on the whole, women explain in these oral histories how fundamental they have been to the Sierra Club’s successes, from its earliest days through the present. Below, I briefly explain some of these themes and offer quotes from various interviews that directly relate to it.

Nature as an Equalizer: At its most optimistic roots, the Sierra Club’s founders appreciated the outdoors and the mutual enjoyment of exploring natural landscapes. Several older female interviewees described early twentieth-century “High Trips” in the Sierra Nevada backcountry as joyous outings where neither man nor woman was restricted to any particular role. Rather, all “outings” attendees contributed as part of an innocuous group that moved through the wild landscape. Women spoke of their physical endurance and the power their own bodies gave them—they led backcountry trips and wore pants before women were “supposed” to be leaders or wear pants! From the Sierra Club’s earliest years, hiking and an intimate connection to the outdoors has remained a means for empowering women.

- Born in 1897, Cicely M. Christy attended her first of many backcountry “High Trip” in the summer of 1938, at age 41. She recalled, “The winter of 1937–38 was one of the very heaviest snowfalls the Sierra has had. They had to change the itinerary of the high trip several times because we couldn’t get over passes. A great deal of our first week’s camping was done at 9000 feet, which is despised at any other time! But it was also one of the first times, the only time perhaps, that I really took a pair of boots to bed with me the first night out, to prevent them from being frozen solid in the morning.”

- Recalling tales from her “High Trips” in the 1920s, Nina Eloesser explained, “There was quite a sizable ‘mountain,’ they called it. We wouldn’t think much of it, but it was about six or seven thousand feet up, and it was called Craig Dhu, which meant the ‘black mountain.’ I used to walk by myself, because mother couldn’t. I walked all over that country.” pg 2

- On climbing Mt. Rainier in the late 1920s, Nora Evans noted, “There were seven men, and I was the only woman. I made it to the top successfully.” pg 6

- When asked in the 1970s about women attending early “High Trips,” Ruth E. Praeger replied, “Oh yes. There were always more women than men … but camp was very different then from what it is now. The sexes didn’t mix as they do now.” pg 8

Pioneering Activism: Many Sierra Club women pioneered the Club’s expanding involvement in various issues, from toxins in the environment, to the intersection of women’s health with environmental issues, to a greater engagement with environmental justice. The social contexts of gender roles often showed when some women spoke on their activist work. Many women expressed concern specifically for their children and generally on public health issues, which reflects a conventional focus of women’s activism. Still, these women nuanced their understanding of how complex environmental issues related to one another and stood at the forefront of pushing the Sierra Club’s involvement on these issues.

- Marjory Farquhar joined her first “High Trip” in 1929 and was elected to the Sierra Club Board of Directors in the 1950s. In 1977, when asked about racial discrimination in her northern Sierra Club chapter versus the southern chapter, she replied, “We were far more loose up here. I don’t really remember anything; I just remember myself once thinking, ‘Oh, there are no Japanese or Chinese here—I wonder if I know anyone who would like to join?’” pg 42

- Asked in 1979 for her thoughts on what the Club’s role should be “with regard to broader environmental issues of urban problems, the energy problem, overpopulation,” Cicely M. Christy answered, “All I can do is quote John Muir that if you take up one thing you find it hitched to the whole universe. I think that the Club can leave urban things to other groups, who are more likely to be interested in the urban things than they are in the outdoor natural things. I think that the Sierra Club’s main objective in life, and the thing that they can do best for this country, is the preserving of open spaces and the good air that will keep the open spaces. If you get air pollution you will find that your pine trees in the Sierra are suffering—well, there is not much good in preserving the pine trees in the Sierra if you can’t reduce pollution on the coast. You have to pay attention to everything.” pg 31

- According to Abigail Avery, the purpose of the Sierra Club’s Environmental Impact of Warfare Committee in the 1980s was “to point out wherever it’s appropriate, the connection between what is happening in this whole military buildup and the effect it’s having on the natural environment. Our traditional concern with the Club has been the natural environment. What effect is all this having on these other issues?” pg 23

- When asked in the early 2000s how the Club develops coalitions with diverse groups outside its traditional middle-class, college-educated membership, Doris Cellarius replied, “Sierra Club, I think, has always had really good sense about this. Any Club member I’ve worked with in the United States who’s working with people at toxic waste sites goes there to be helpful. We don’t go there to make them be members. We’ve never—this is just something Sierra Club does to be helpful. We want a clean environment, and we love to work with you. That’s continued to be the tradition of our environmental justice work.” pg 43

Women as Nurturers and the Cult of Domesticity: Women activists in the Sierra Club engaged on a variety of environmental issues, but sometimes historical gender conventions limited the scope of their work or shaped the motivation behind it, particularly with issues linked traditionally to women such as children’s health and “nurturing” others. This view of gender roles and subscription to them can be traced back to the “Cult of Domesticity” or the “Cult of True Womanhood”: a framework of gender stereotypes demarcating women as the gatekeepers of the home, the moral compass of society, and generally as nurturers of the public. In several Sierra Club interviews, women described their environmental activism with both overt and subtle explanations either of ways they felt restricted or ways they chose to engage in the Club based on these gendered stereotypes.

- Reflecting on her environmental experiences after her marriage, Marjory Farquhar said, “I will admit that my active rock climbing days disappeared, really perhaps for two reasons: one because I went into the baby-production business, and the other because of the war.” pg. 22

- When asked about the start of her activism in the 1940s, Polly Dyer replied, “I got involved in conservation by meeting [my husband] John Dyer on top of 3000-foot Deer Mountain [in Ketchikan, Alaska] … Conservation by marriage. I would have gotten into it eventually, I presume, but at least it was an introduction.” pg 2

- Abigail Avery became active in preserving national parks. In 1988, then in her 70s, she recalled how “[My husband Stuart] was the one who first got interested in the [Sierra Club’s] Atlantic Chapter, which was the only chapter in this Eastern area at that time. I remember going on trips with him, but I would go as a wife, you see … I hadn’t really looked at conservation. What I really was concentrating on during that time after Stuart got back [from WWII] was having the rest of my family. Really you cannot maintain everything. You’re not free to do it. So there’s a hiatus in there.” pg 4

- Doris Cellarius shared her view on how gender fits into the environmental movement and what women might bring to it different from men: “I think women just seem to care a lot more about—in the pollution area—about what happens to people, what happens to children. They think more of the long-term consequences of things, and I think they get more outraged that it’s all these men in the corporations that really just enjoy creating these chemicals and building these things that are problems. But I think they have more of an outrage that these things shouldn’t be done to the environment or to people.” pg 53

Leadership and Gender: Interviews with women focused on their work within the Sierra Club, and several interviews dedicated an entire section to the role of women in leadership positions within the Club. Women discussed the expansion of female leadership, limitations, and regressions. Many interviews explored how the narrator felt about their role and the future directions for women in the Club.

- In 1982, then 85 years old, Cicely M. Christy noted, “On the whole, positions of chairmen [of the Sierra Club Board of Directors] have gone to men until a few years ago, and then people like Helen Burke came in. … [Before the 1970s, women’s work in the Club] was just reflected in each chapter I think. I think people grew out of [that tendency to vote for men], rather deep laid, not exactly prejudiced, but just habits of thought.” pg 34

- In 1979, at age of 38, Helen Burke became an elected Executive Officer on the Sierra Club’s National Board of Directors, while also serving as Board liaison to the Club’s Women’s Outreach Task Force and the Urban Environment Task Force. When asked about women’s leadership within the Club, she replied, “The Club has, in the past, been a rather male dominated institution. I think that’s changing now. We presently have four women on a [National Board of Directors] of fifteen, which is roughly a little over one-fourth. I have some statistics which I can find for you in terms of active women on the Executive Committees, etc. Those percentages are going up. But at any rate, I think that the Women’s Outreach effort has an aspect of being a kind of support group for women within the Sierra Club.” pgs 3–4

- For ten years, Doris Cellarius chaired the Club’s Hazardous Waste Advisory Committee. In 2001, she recalled when younger that, “I didn’t feel any need to go out and arm myself as a militant feminist. … I was busy, and I have very little experience with women who had problems … But I really began to feel it when I worked with these women at toxic waste sites and saw that it was mostly women. I saw how the people from the agencies were mostly men, and they didn’t take the women too seriously. It never made me feel it was a gender thing, though; I thought it was more government oppressing the citizens and treating them like something in the way of getting their job done.” pg 63

- In 1979, amid national efforts to secure an Equal Rights Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, Helen Burke declared, “The more men see capable women, qualified women elected to the Board [of Directors], the more they will see that women are able to carry significant burdens, etc. That’s what women’s liberation is all about.” pg 15

More work remains, both for women in the Sierra Club and on this oral history research project. I plan to continue this research next semester to comb through more Sierra Club interviews and further compile an annotated outline of themes and examples. My goal is to organize this rich archive of Sierra Club women’s oral histories so future scholars and interested people can better understand the Club’s growth—in size and especially in scope—through the narratives of its female members.

— Ella Griffth, UC Berkeley, Class of 2020

A Story of Science: Oral History Undergraduate Research

“A Story of Science”

(Undergraduate Research Apprentice Program, Spring 2019)

By Caitlin Iswono

Caitlin Iswono is a rising junior at UC Berkeley majoring in Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering. In the Spring 2019 semester, Caitlin worked with historian Roger Eardley-Pryor of the Oral History Center and earned academic credits as part of UC Berkeley’s Undergraduate Research Apprentice Program (URAP). URAP provides opportunities for undergraduates to work closely with Berkeley scholars on the cutting edge research projects for which Berkeley is world-renowned. Caitlin provided valuable research for Eardley-Pryor’s science-focused oral history interviews. Here, Caitlin reflects on her URAP experience in the Oral History Center.

As a chemical engineering student at the University of California, Berkeley, I usually write technical lab reports and experimental analyses of scientific data. But last winter, before the Spring 2019 semester, I decided to examine science from a different perspective. While glancing through different topics of interest for a prospective Undergraduate Research Apprentice Program (URAP) project, I became fascinated by the science interviews conducted by the Oral History Center. Science is perceived to be objective and impartial, based only on “real facts.” But what are the personal reasons behind a scientist’s work? And what are the human elements that help produce scientific facts? After working on several oral history projects this semester, I learned that the process of science is actually a story, and every experiment has a riveting history and person behind it.

My URAP project this semester consisted of research preparations for oral history interviews conducted by Roger Eardley-Pryor, a historian of science, technology, and the environment in the Oral History Center. I conducted background research on the scientific work of two different kinds of chemists. Alexis T. Bell, a renowned professor and former chair of UC Berkeley’s Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, was one of two oral history interviewees whose research I examined and explained. Since joining Berkeley’s faculty in 1967, Alexis Bell has and continues to conduct complex and comprehensive research in hydrogenation, electrocatalysis, zeolite synthesis, and theoretical applications for chemical engineering. His reports and publications are meticulous and highly revered in academia. Bell’s scientific work is prominent in the scientific world. But what was his personal story?

This question is what I helped explore during the Spring 2019 semester. Professor Bell recorded his scientific methods and experimental results in his numerous publications, but the personal story behind his work would best reveal itself through his oral history interviews. My task was to conduct background research on Bell’s publications and ask fruitful questions on the driving forces behind his vast range of experiments. Together, historian Roger Eardley-Pryor and I researched topics including the inspirations, funding, technological advancements, and partnerships in each of Bell’s projects. By reading Bell’s scientific articles and designing questions that linked the scientific work with his motivations, I learned that science cannot be fully comprehended unless the driving force behind the published lab report is made clear. These “behind-the-scenes” and human connections within the scientific process contribute to the world of academia in ways just as significant as the scientific analyses.

My background research on another chemist named Michael Schilling unveiled additional fascinating stories. As a senior scientist at the Getty Conservation Institute, some of Schilling’s projects included preserving hand-drawn Disney animation cels as well as identifying biological materials used to make ancient Asian lacquers that, later, eighteenth-century French craftsmen incorporated into furniture for King Louis the XIV. Schilling’s riveting analytical chemistry seemed far afield from the work I imagined most materials scientists do. I grew increasingly interested to hear Schilling share his personal history and explain how he came to work on these projects.

My initial reading of Schilling’s published work left me curious to how and why he conducted such diverse projects in art conservation. I grasped the technical aspects of Schilling’s work, but I found myself asking “Why did he do this as a chemist? Why was this his topic of interest and who initiated it?” As I learned more about Schilling’s personal background and the steps he took to achieve his career accomplishments, I could better understand the timeline and motivations behind his work. Those motivations and the processes before lab work began are not found in published reports, but only through Schilling recounting his own history and life contexts. Here was another example of science and oral history joining together to reveal the human aspects in the scientific process.

Assisting UC Berkeley’s Oral History Center as an undergraduate research apprentice this semester was personally rewarding. Weekly meetings with Dr. Roger Eardley-Pryor helped me grasp more than just the “technical” parts of science. Analyzing lab reports is not enough to understand the bigger picture and the human processes of science. Instead, we sought answers to “Why? For what purpose? How? For whom? With whom?” Questions like these can help explain why and how new scientific knowledge is produced.

I also learned valuable skills and broader applications for the scientific knowledge taught in my chemical engineering courses. For example, while researching different analytical methods of mass spectroscopy for Alexis Bell’s oral history, I realized I had prior experience implementing these methods in my own laboratory courses. Although classes taught me the procedures and practical uses of this instrument, they lacked a broader perception on the people who use it and why they did so. While assisting these oral history projects and seeking insight into the entire scientific process, I discovered the driving forces behind an experiment, not merely the technicality and practice of it. Motivations, people, and personal connections provide backbone to the scientific process. As a result, I can now practice my lab class experiments and analyze why I’m conducting it, to look beyond the procedures, to find its purpose.

My URAP experience in the Oral History Center helped me become more open-minded and curious about different fields of science. My perceptions of the scientific process broadened beyond the laboratory. In short, I discovered that science has human history. On its surface, science provides facts based on experimental results and controlled environments. But behind that veil is a human who discovered that scientific knowledge. That person’s individual experience and perspective help explain more fully the meaning their science strives to comprehend. Without the history and influences of an experiment, questions remain unanswered. The combination of experimentation, observation, history, and human experience—all together—produce the world of science. And that is the story that we must read. That is the story I helped shape last semester at the Oral History Center.

— Caitlin Iswono, UC Berkeley, Class of 2021

From the Archives: C. Judson King

“Freeze-Dried Turkey, Food Tech, and Futures”

by Caitlin Iswono

Caitlin Iswono is a sophomore undergraduate student at UC Berkeley majoring in chemical engineering. In the Spring 2019 semester, Caitlin worked with historian Roger Eardley-Pryor of the Oral History Center and earned academic credits as part of UC Berkeley’s Undergraduate Research Apprentice Program (URAP). URAP provides opportunities for undergraduates to work closely with Berkeley scholars on the cutting edge research projects for which Berkeley is world-renowned. Caitlin provided valuable research for Eardley-Pryor’s science-focused oral history interviews this past semester. Caitlin’s explorations of the Oral History Center’s existing interviews resulted in this month’s “From the Archives” article.

“I had my turkeys. I think I may still have a piece of freeze-dried turkey that’s now fifty years old.”

— C. Judson King, “A Career in Chemical Engineering and University Administration, 1963-2013,” oral history interviews conducted by Lisa Rubens and Emily Redman, with Sam Redman, in 2011, Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 2013.

In 1963, at age 29, C. Judson “Jud” King was backpacking in California when a fellow Boy Scouts Master revealed he freeze-dried his food before weeklong trips to the Sierra Mountains with groups of ten to twelve people. While the levels of safety and sanitation were not like today’s freeze-dried food, this period in King’s early adulthood sparked a branch of his later academic research that opened new discoveries and advancements in the food-technology industry. Like King’s connection with hiking and freeze-drying, I also aspire to coalesce my personal interests—namely, in humanitarian aid—with research in food technology for my future career.

King, a professor emeritus of UC Berkeley’s Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, held positions in a wide variety of academic and administrative posts. Throughout his career, King served as the Provost and Senior Vice President of Academic Affairs of the University of California system, as Dean of the College of Chemistry at UC Berkeley, and as Chair of Berkeley’s Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering. With over 240 research publications, including a widely used chemical engineering textbook, 14 patents, and major awards from the American Institute of Chemical Engineers, King has lived an accomplished life. But how did he get started in chemical engineering? And what might a chemical engineering student like me take from his experiences?

When asked in his 2011 oral history interview why he chose chemical engineering, King simply answered “I like chemistry. I like math. What should I look to major in college? The answer was chemical engineering.” King’s statement rings true for me, too. As an incoming freshman to Berkeley in 2017, I knew I would major in chemical engineering, but I was unsure what I wanted to do with this degree. In Cal’s rigorous chemical engineering program, I occasionally lost sight of the bigger picture. Constant midterm cycles, weekly problem sets, daily academic tasks, and my broader student activities all made it easy to avoid exploring why I’m pursuing my chemical engineering degree and what I hope to accomplish with it. However, learning from the experiences and insights of upperclassmen, graduate instructors, and my professors, I’ve found new purpose and aspirations for my future.

Not unlike King, I also became interested in food technology. My interest in food-tech began after attending Berkeley’s on-campus UNICEF Club and hearing guest lectures on the profound effects advanced food technology can have for developing countries. UNICEF is a United Nations organization charged with protecting children’s rights and helps over 190 disadvantaged territories around the world. It does so, in part, by incorporating food science and technology in their efforts to assist malnourished children, particularly with Ready to Use Therapeutic Foods (RUTF). Learning about this advancement sparked my interest in food science, similar to how hiking inspired King’s research transition to freeze-drying foods. King’s successful research and collaborations with companies such as Proctor and Gamble opened my mind to new possibilities. Reading King’s oral history interview and discovering his experiences in diverse fields within chemical engineering provided guidance on a possible career path for me.

King’s oral history also offered insight on different processes of freeze drying and how they influenced history. As King explained it, the development of freeze-dried techniques did not emerge from a desire for portable food. Rather, it arose from efforts to preserve medicines and blood plasma cells for medical reasons, particularly from isolating and stabilizing penicillin during World War II. Only after World War II ended did industries utilize freeze-drying to preserve foods. Industrial processors and academics like Jud King realized that freeze-drying techniques could apply to many fields, whether for military use, backpacking, space travel, or pharmaceuticals. These realizations have since inspired me to combine my passions for UNICEF advocacy and food technology to positively impact underdeveloped countries.

King’s interview reminded me that every person starts from somewhere and it’s okay to not have the entirety of life figured out from the very beginning. King’s interests in freeze-drying led to him becoming a renowned professor emeritus and former dean of Berkeley’s College of Chemistry. His story reminded me that the most anyone can do is strive to learn new things, try your hardest, and take on new opportunities. Your path and future track will then build itself.

— Caitlin Iswono, UC Berkeley, Class of 2021

Oral History Center – From the Archives: Charles H. Warren

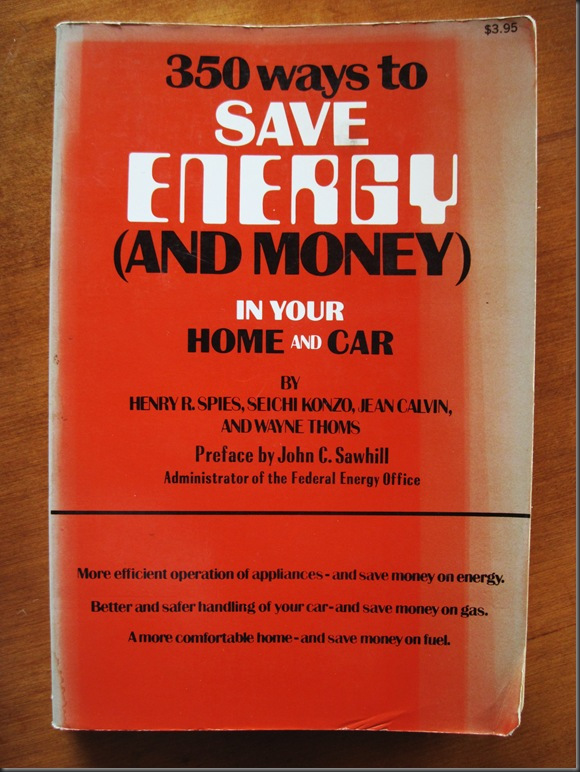

Charles H. Warren and California Energy in the “Era of Limits”

Charles H. Warren, “From the California Assembly to the Council on Environmental Quality, 1962-1979: The Evolution of an Environmentalist,” an oral history conducted in 1983 by Sarah Sharp, in Democratic Party Politics and Environmental Issues in California, 1962-1976, Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 1986.

Over the past half-century, California’s electric utility companies have experienced waves of change, challenge, and crisis while producing power and earning profits for their shareholders. Most recently, the San Francisco-based Pacific Gas and Electric Company (PG&E)—one of the largest investor-owned utilities in the United States—began 2019 seeking chapter 11 bankruptcy protections in lieu of deaths and damages from destructive wildfires for which it may be liable. PG&E last declared bankruptcy in 2001 during the California energy crisis under quite different and convoluted circumstances, including the convergence of severe drought, high temperatures, and pricing manipulations derived from poorly designed deregulation of California’s energy markets in the mid-1990s. The energy crisis in the 1970s, however, stands out for its onslaught of economic, environmental, and political overlap, which left many businesses and policy-makers at a loss with how to cope and move forward.

By 1976, fuel shortages and forecasts of rolling blackouts from California’s utilities spurred then Democratic Gubernatorial candidate Jerry Brown to characterize the 1970s as “an era of limits.” From 1962 through that “era of limits,” Charles H. Warren served as a leading Democrat in California’s Assembly. Warren’s legislative response to California’s energy issues in the 1970s gained national recognition and led him, in 1977, to join President Jimmy Carter’s cabinet as chair of the Council on Environmental Quality. Warren addresses all this in his oral history interview, recorded in the early 1980s. Amid new energy challenges facing California’s utilities today, revisiting Warren’s oral history reveals how one legislator in California’s Assembly confronted the 1970s energy crisis, sometimes supporting and other times challenging California’s powerful utility companies.

Most memories of energy in the “era of limits” trace back to October 1973 when Saudi Arabia and other Arab nations in OPEC—the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries—halted exports of crude oil to the United States and its allies. Arab members of OPEC initiated their embargo as punishment for American military support of Israel after Syria and Egypt launched a surprise attack against the the Jewish state on Yom Kippur. OPEC’s oil embargo lasted only from October 1973 through the spring of 1974, but it sent shock waves throughout the industrialized world. For one, the price of oil suddenly quadrupled. The U.S. economy contracted, throwing millions of Americans out of work, while those who kept their jobs saw minuscule progress on wages. As a member of California’s assembly, Charlie Warren played an outsized role in drafting California’s legislative and regulatory responses to the 1970s energy crisis. Yet in his 1983 oral history interview, Warren explained how California’s utilities expected critical energy shortages much sooner than you might expect.

A few years before the OPEC oil embargo, California’s electric utility companies warned state legislators of a separate impending energy crisis. Warren recalled, “during 1971, the major electric utilities in California, PG&E, Southern California Edison, and San Diego Gas and Electric, advised legislative leaders that unless the state took certain action, in the foreseeable future there would be shortages of electricity with resulting brownouts and blackouts of indefinite duration.” The problem, according to the utilities, was that regional and local governments in California made it increasingly difficult to site new and necessary power stations, particularly new nuclear plants fueled by uranium. In response, the utilities succeeded in passing legislation through the California Senate that would preempt the jurisdiction of local governments and regional agencies for siting new power stations. In the Assembly, that legislation came to the Planning and Land Use Committee on which Charlie Warren served. Warren and fellow committee-members feared the utilities’ energy forecasts but felt reluctant to approve legislation that removed local control for locating power plants and put it the hands of a new state agency, as requested by California’s utilities. The committee decided the issue required deeper investigation.

Warren found himself chairing a new subcommittee on energy that contracted with the Rand Corporation in Santa Monica to evaluate California’s electrical energy system and the utilities’ anticipated crisis. The Rand Corporation had, until that time, exclusive contracts with the U.S. military for complex systems analyses, especially scenarios involving global nuclear war. Yet Rand began expanding their research into the non-military policy area, and this contract with California’s state government afforded an early opportunities to do so. Warren’s subcommittee received the Rand report in October 1972, and as he recalled, “I was so startled by its findings that my life was changed.” Warren’s responses to this report reshaped regulation of California’s energy landscape and catapulted him to national attention as a legislative expert on energy issues.

The Rand report substantiated the utilities’ anticipated energy crisis. According to Rand’s analysis, California’s annual demand for energy was growing so rapidly—and was forecast to expand at similar rates over the next twenty years—that avoiding projected blackouts would require all of California’s then-existent electricity production to double every ten years. That is, the entire capacity of California’s electric output would need to completely replace itself every decade, all while maintaining its existing output. To make matters worse, the Rand report also noted how the traditional means of generating electricity with natural gas and low-sulfur crude oil were becoming increasingly scarce and more expensive (even before the OPEC embargo restricted the availability of crude oil and quadrupled its price!) Rand further reported that, in response to these anticipated challenges, California’s utilities planned to generate this additional energy with scores of new nuclear power plants. The utilities projected that, by the year 2000, an additional one hundred large power plants would be required throughout California, at least eighty of which they imagined would run on nuclear fuel.

Before deregulation of California’s energy markets in the 1990s, utilities operated as profitable, state-sanctioned monopolies. For California’s investor-owned utilities like PG&E and SoCal Edison, a surge of newly constructed power plants would not just meet the state’s rapidly growing energy needs, it would substantially boost the utilities’ bottom line. At the time, most Americans had limited knowledge or concern about nuclear energy. Indeed, most Americans in the early 1970s still believed nuclear power would provide energy too cheap to meter and do so without significant consequences. However, the Rand report expressed considerable apprehensions both about nuclear generator technologies and reliance on nuclear energy to the extent California utilities thought necessary.

In the spring of 1973, Warren initiated a series of California Assembly hearings on the findings in the Rand report. The hearings, Warren recalled, “were lengthy, time consuming, and adversarial.” But as a result, Warren learned a great deal on the deep economic, environmental, and political complexities involved in energy production and use. Among other things, Warren realized “it would be imprudent to rely on nuclear to the extent the utilities then planned.” Rather than endlessly construct new nuclear stations or build new power plants that ran on dirty and increasingly expensive fuels, Warren imagined a program of increased efficiency through energy conservation and efforts for alternative energy. Warren also realized, however, that the combined influence of California’s utilities and the public’s limited knowledge on nuclear issues made it “politically impossible to make a case against nuclear in order to justify a program of energy conservation and energy alternatives development.”

Instead, Warren drafted new legislation for substantial changes to state energy policies that, without mentioning nuclear power, relied on significant land use and water requirements for the siting and operating of new power plants. Overcoming his initial hesitations for a new state entity, Warren’s legislation proposed a new energy agency that would adopt conservation measures in all electricity consuming sectors; it would encourage the development of alternative energy resources, specifically solar and geothermal; and it would conduct independent energy forecasts for electricity similar to what the Rand report did. After some additional amendments, Warren’s legislation passed both the California Assembly and Senate.

By early Autumn in 1973, Warren’s legislation arrived on the desk of California Governor Ronald Reagan, who vetoed the bill. Within a few weeks, however, the OPEC oil embargo suddenly made energy a serious political concern. Reagan’s staff realized Warren’s bill had merit and regretted its hasty veto. The governor’s office soon contacted Warren to create a new policy together that would confront the energy crisis—a crisis that California’s utilities had in some ways anticipated. Over a period of several weeks, Warren began “extended negotiations with the governor’s staff, and with the governor personally,” as well as intense meetings with utility representatives, legislative staff, and state agency officials. Together, they produced what became known as the Warren-Alquist State Energy Resources Conservation and Development Act, or Assembly Bill 1575, which was markedly similar to Warren’s earlier bill that Reagan first vetoed.

California’s utilities disliked AB1575, but they supported it at Reagan’s insistence. “The governor’s support,” Warren remembered, “was at some political cost to himself. I recall a staff person who had been given responsibility for energy policy resigned and Lieutenant Governor Ed Reinecke who was campaigning for governor publicly announced his opposition. But Reagan kept his word.” With the governor’s aid, AB1575 moved through California’s Assembly and, by a margin of one vote, it found approval Senate in 1974. This time Reagan signed it, marking the nation’s first substantial legislative effort to confront the 1970s energy crisis—not through inefficient if profitable new power plants for utility monopolies, but through energy conservation, increased analyses, and pursuit of alternative energy sources.

The enactment of the Warren-Alquist Act in 1974 strengthened California’s leadership in the management and production of power. Among other things, the bill created the California Energy Commission, formally the Energy Resources Conservation and Development Commission, which remains California’s primary energy policy and planning agency. It set forth state policies concerning the generation, transmission, and consumption of electrical energy and established a comprehensive administrative procedure for review, evaluation, and certification of power plant sites proposed to meet forecasted power demands. According to Warren, the bill was also “the first to challenge the policies of energy inefficiency of the utilities and to point out that energy planning by the utilities was devoted more to maximizing profits than to the public’s interest in a rational and reasonable energy program. It did this by establishing a state energy agency [the California Energy Commission] responsible for energy demand by forecasting, energy conservation and efficiency standards, development of alternative energy supply systems, and simplifying and shortening the process for siting power plants.”

Charles Warren’s oral history continues to outline his additional experiences drafting formative policies in the 1970s that reordered the ways utility producers and energy-consumers conduct business and use resources in California. In 1975, Warren helped draft the Utilities Lifeline Act, by which each residential user of electricity and gas in California would receive a minimal supply of energy at a discounted price but would pay a higher price for energy taken in excess of that minimum. In 1976, Warren drafted the Nuclear Safeguards Act, which still prohibits new nuclear plants from being built in California until the federal government establishes a permanent storage for high-level radioactive waste. Also in 1976, Warren drafted the California Coastal Act, which made permanent the California Coastal Commission’s mandate to enhance public access to the shoreline, protect coastal natural resources, and balance both development and conservation. Today, as California’s utilities struggle to adapt to climate change and to increasingly dynamic markets for energy production, reading Warren’s oral history unveils how one California legislator sought expansive solutions to energy issues and resource challenges during the 1970s “era of limits.”

by Roger Eardley-Pryor, PhD

Oral History Center of the Bancroft Library

Charles H. Warren, “From the California Assembly to the Council on Environmental Quality, 1962-1979: The Evolution of an Environmentalist,” an oral history conducted in 1983 by Sarah Sharp, in Democratic Party Politics and Environmental Issues in California, 1962-1976, Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 1986.

New Release Oral History: Howard R. Friesen, UC Berkeley alum (1950), engineer, entrepreneur, and philanthropist

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library is pleased to release our life history interview with engineer, entrepreneur, and alumnus and philanthropist of UC Berkeley, Howard R. Friesen.

Howard R. Friesen earned his engineering degree from UC Berkeley in 1950. He eventually worked to own G. J. Yamas Company, Inc., which became one of the largest independent businesses in California and Nevada that specialized in building automation, controls systems, and related equipment for commercial and industrial buildings. As told in this interview, Mr. Friesen’s career in the building industries from 1950 through 1980 contributed to influential developments across California, from the construction of new schools amid the Baby Boom to evolving relations with organized labor, and from the rise of high-tech manufacturing in Silicon Valley to the expansion of California’s prison system.

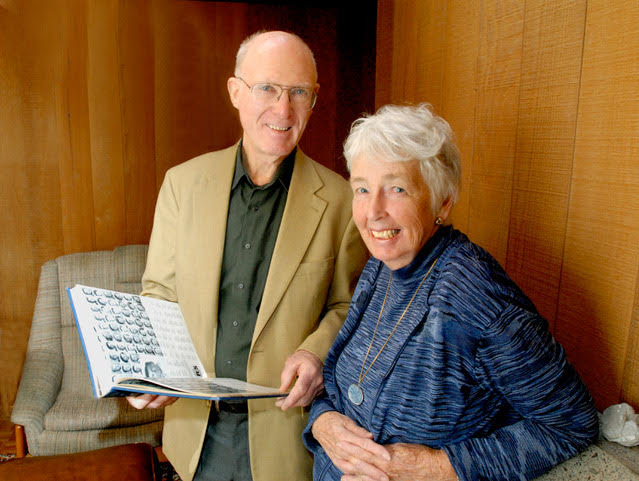

Mr. Friesen also describes childhood memories working on his family’s farm in Reedley, California during the Great Depression, including leasing a farm in the 1940s from an interned Japanese family. He discusses his travels around Chicago and through Jim Crow-era Mississippi during his Naval training for World War II. Upon the war’s conclusion and with support from the G. I. Bill, Mr. Friesen then earned his engineering degree at UC Berkeley, where he met Candy Penther, his wife for more than sixty years. Most of this interview recounts Mr. Friesen’s career with G. J. Yamas Company, which he helped expand to five locations across California and Nevada. Mr. Friesen also addresses his and Candy’s generous philanthropy to UC Berkeley for student scholarships, endowment of research chairs, and significant contributions to The Bancroft Library and the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA). Candy passed away in 2015 after a difficult battle against Parkinson’s Disease.

Mr. Friesen’s interview reveals how a farm boy from Reedley participated in several of the twentieth century’s great events—from World War II to the Microelectronics Revolution—and, with his wife, came to donate millions of dollars to UC Berkeley so others might pursue their own dreams of success.

— Roger Eardley-Pryor, PhD (November 2018)