Tag: BL East Asia

Classical Chinese

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

題名雁塔代有其人

In every generation there are those who inscribe

their names on the Wild Goose Pagoda.

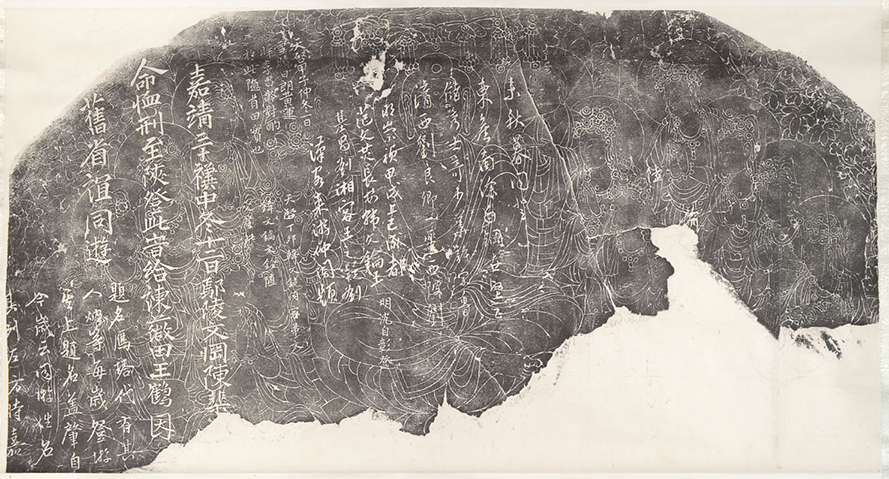

In 629, the Buddhist monk Xuanzang journeyed to the west in search of religious texts. Sixteen years later he returned to the Tang capital at Chang’an (modern Xi’an) with hundreds of Sanskrit sutras that would have to be rendered into Chinese. Emperor Gaozong invited the monk to base his translation project at the Big Wild Goose Pagoda on the grounds of Ci’ensi, a temple with strong ties to the throne and accordingly adorned with religious sculpture and textual engravings of the highest quality.

At that time, successful civil-service examinees were known to write their names on the pagoda walls with brush and ink. This custom evolved into something more durable in the centuries following the dynasty’s collapse in 907. Chang’an then lost its preeminence and much of its population, although it remained a site of historical and cultural interest. Visitors invariably stopped at the pagoda to view the surroundings from its upper stories. Some left their autographs there as well, carved over the Buddhas and divine attendants in the lintels surmounting the four entrances to the building—a practice that might have alluded to past privilege and accomplishment, but also to the city’s diminished status and the uncertain course of power.

This rubbing and dozens of others were given to the East Asian Library by the bequest of Woodbridge Bingham (1901–86), professor of history and founder of the Institute of East Asian Studies. Before the establishment of the East Asian Library, the campus community depended on faculty like Bingham, Ferdinand Lessing, and Delmer Brown, to help develop its collections: they left for sabbaticals abroad with lists of desiderata; once overseas, they sacrificed research hours haunting bookstores, searching out collectors willing to sell, wrangling with customs officials. At the end of their careers, many left their own collections to the university, building on the foundation that they had helped lay.

Contribution by Deborah Rudolph

Curator, C. V. Starr East Asian Library

Title: Dayan ta fo ke ji ti ming 大雁塔佛刻及題名

Title in English: Reliefs and inscriptions from the lintels of the Big Wild Goose Pagoda

Authors: Anonymous (artwork); multiple authors (textual inscriptions)

Imprint: 20th-century rubbing of Tang dynasty pictorial relief, with textual inscriptions dating from the Song through the Ming dynasties

Language: Chinese

Language Family: Sino-Tibetan

Source: C. V. Starr East Asian Library (UC Berkeley)

URL1: http://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/stonerubbings/ucb/images/brk00024200_32b_k.jpg

URL2: http://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/stonerubbings/ucb/images/brk00024198_32b_k.jpg

Other online editions:

- The East Asian Library’s rubbings of the lintels have been digitized and added to its online catalog of the rubbings collection, at http://www.lib.berkeley.edu/EAL/stone/index.html

- A series of photographs and details of the reliefs can be found on the blog site sina.com, at http://blog.sina.com.cn/s/blog_91ea73640102x92v.html (accessed 6/1/20)

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Korean

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

This manuscript consists of four autobiographical narratives written by Lady Hyegyŏnggung Hong Ssi, an 18th-century Korean noblewoman. Considered both a literary masterpiece and an invaluable historical document, the memoirs were translated into English by JaHyun Kim Haboush with the title The Memoirs of Lady Heygyŏng (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996).

A story is told through personal anecdotes, written between 1795 and 1805, of Lady Heygyŏng’s life in the palace and about tragic happenings to members of her family. She was married to the crown prince of King Yŏngjo (1694-1776; reigned in 1744-1776). In the summer of 1762, her husband and apparent heir to the throne was falsely accused of plotting against Lady Heygyŏng’s father, and was placed in a sealed rice chest in which he suffocated. Soon after this tragedy, King Yŏngjo regretted his harshness and gave his daughter Hong Ssi the title of Royal Consort Hyegyŏnggung.

Historical and modern linguists classify Korean as a language isolate with linguistic roots in Manchuria. Prior to 1433/34 when King Sejon of the Chŏsun Dynasty invented the remarkable alphabet known to southerners as hangŭl and to northerners as chŏsongŭl, all writing in Korea was done in the Chinese script.[1] In the 17th century, it evolved into modern Korean, with considerable phonological differences from Middle Korean.[2] Rather than being composed in literary Chinese as were most writings by men before the modern era, Lady Heygyŏng’s memoirs were composed in Korean, in han’gŭl script, making them accessible to the modern reader.

As the official language of both South and North Korea, Korean is the native language of more than 77 million people worldwide.[2] The Library’s Korean holdings exceed 102,000 volumes. Outstanding among these are the 4,000+ volumes of the Asami library, assembled by Asami Rintarō in the early decades of the 20th century and purchased by the Library 30 years later.[3] In 1942, UC Berkeley became the first university in the country to offer instruction in Korean, which continues to be taught for all academic levels in the Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures.

Contribution by Jaeyong Chang

Librarian for the Korean Collections, C.V. Starr East Asian Library

Sources consulted:

- Garry, Jane, and Carl R. G. Rubino. Facts About the World’s Languages: An Encyclopedia of the World’s Major Languages, Past and Present. New York: H.W. Wilson, 2001.

- Dalby, Andrew. Dictionary of Languages: The Definitive Reference to More Than 400 Languages. New York: Columbia University Press, 1998.

- Ethnologue: Languages of the World (accessed 6/3/19)

- UC Berkeley Center for Korean Studies

~~~~~~~~~~

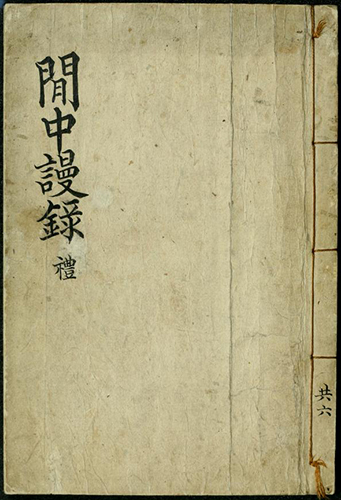

Title: 한중만록 (Handyung mannok)

Title in English: Memoirs Written in Silence

Author: Hyegyŏnggung Hong Ssi (1735-1815)

Imprint: Korea : [s.n., 18–?]

Edition: 1st

Language: Korean

Language Family: Koreanic

Source: The Internet Archive (UC Berkeley)

URL: https://archive.org/details/handyungmannokkw01asam

Select print editions at Berkeley:

Handyung Mannok: Kwŏn 1-6. Korea: publisher not identified, 1800. East Asian Rare ASAMI 22.29 1-6

The Memoirs of Lady Hyegyŏng: The Autobiographical Writings of a Crown Princess of Eighteenth-Century Korea. Translated into English by JaHyun K. Haboush. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996. Also available as an ebook.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Japanese

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

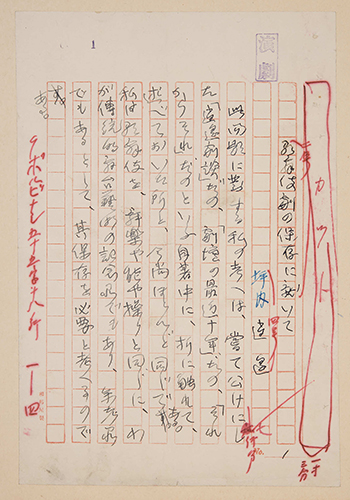

Shōyō wrote the manuscript “On the Preservation of Kabuki Drama” in late March 1924 at the request of Yamamoto Yūzō, the editor of Engeki shinchō, and the essay was published in the journal in June of that year. In his essay, Shōyō addresses what had become for him, by the 1920s, a seminal problem: kabuki was treated as a single art (like nō theater) but, Shōyō felt, the dramatic form had changed significantly over time, from its origins in the early seventeenth century through the early twentieth century. Thus before one could address how to preserve kabuki one needed to determine which aspects of the dramatic art ought be persevered as most representative. Shōyō’s own stance was clear: the “zenith” of the art was in the late eighteenth century and what followed — from the early 19th century onward — was a gradual decay. Thus preservation was perhaps not the right word since what Shōyō sought was really to revive the form of kabuki that had disappeared already over a century earlier.

Shōyō had developed an interest in questions related to the preservation (hozon) of kabuki in the late 1880s and it would remain a concern across his career as playwright, critic, and historian of drama. And yet the timing of “On the Preservation of Kabuki Drama” is also interesting from a historical perspective. The piece was written just six months after the Great Kantō Earthquake destroyed large sections of the city of Tokyo and many writers — Akutagawa Ryūnosuke chief among them—lamented the loss of cultural heritage that resulted from the earthquake and resulting fires. When the earthquake hit on September 1, 1923, Shōyō was at Waseda University in a meeting with Takata Sanae, the University’s president, discussing an exhibition of theater material that was to be held in October. Within days of the earthquake, Shōyō had decided to donate his own private collection of books and theater ephemera to Waseda, the university at which he had taught his entire career. In 1928, with the help of students, friends, and the university, Shōyō was able to realize his long-term goal of creating a theater museum on the campus of Waseda University. The Museum was intended “preserve, as a form of history, Japan’s theater which is incomparable in form in the world and which has developed along a unique path.” Thus while Shōyō may not have achieved his idea of preserving kabuki of the late eighteenth century as a living dramatic art, today the Waseda University Tsubouchi Memorial Theater Museum plays a critical role in preserving the history of kabuki through an unparalleled collection of archival materials.

Contribution by Toshie Marra & Jonathan Zwicker

Librarian for Japanese Collection, C. V. Starr East Asian Library

Associate Professor, Department of East Asian Languages & Cultures

Title: Kabukigeki no hozon ni tsuite 歌舞伎劇の保存に就いて

Title in English: On the Preservation of Kabuki Drama

Author: Tsubouchi, Shōyō 坪内逍遥, 1859-1935

Imprint: Atami, Japan, 1924. 14 leaves. Hand-written manuscript. From UC Berkeley Library (accession number: JMS 1474, East Asian Rare)

Language: Japanese

Language Family: Japonic

Source: The Digital Humanities Center for Japanese Arts and Cultures (DH-JAC) at Ritsumeikan University

URL: http://www.dh-jac.net/db1/books/results1024.php?f1=UCB-ms1474&f12=1&enter=berkeley&max=1&skip=2&enter=berkeley

Other related print editions at Berkeley and online:

- Waseda University Tsubouchi Memorial Theater Museum: https://www.waseda.jp/enpaku/en/

- Tsubouchi, Shōyō, 1859-1935. Tōsei shosei katagi: ichidoku santan 当世書生気質: 一読三歎 . [The Characters of Today’s Students]. Tokyo: Banseidō, 1885-1886. 17 volumes. Digital images made available by the National Diet Library: http://dl.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/887427 (v. 1)

- Author’s original sketch of the illustration for this work is made available by Waseda University Library:

- http://www.wul.waseda.ac.jp/kotenseki/html/bunko14/bunko14_b0067/index.html

- http://www.wul.waseda.ac.jp/kotenseki/html/bunko14/bunko14_b0066/index.html

- http://www.wul.waseda.ac.jp/kotenseki/html/bunko14/bunko14_b0037/index.html

Note: UC Berkeley has later editions of this work for use at the East Asian Library (EAL):

- Tsubouchi, Shōyō, 1859-1935. Shōsetsu shinzui 小説神髄. [The Essence of the Novel]. Tokyo: Shōgetsudō, 1887. 2 volumes. Digital images made available by the National Diet Library: http://dl.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/987668

Note: UC Berkeley’s copy available for use at EAL: http://oskicat.berkeley.edu/record=b10214836~S

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Chinese

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

The concept of “children’s literature” was virtually foreign when Chao’s translation of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland first appeared in China. Traditionally, children of the literate classes learned to read by memorizing and copying out primers, like the Three Character Classic 三字經, gradually moving on to the Confucian canon, dynastic histories, and standard compendia of classical literature. What fiction they read was written for adults.

This changed with the May Fourth Movement of 1919, which called for a number of reforms, including the use of vernacular, rather than classical, Chinese in all forms of writing. Some of the movement’s leaders further called for the development of a literature written for children, whether to free them of the intellectual constraints of traditional education, or to give them a psychological space of their own. First published in 1922, Chao’s translation of Alice can be viewed as an answer to both calls.

Alisi is not simply an historical artifact, however. As a linguist (albeit one who took degrees in mathematics and philosophy from Cornell and Harvard), Chao understood well the challenge of Carroll’s language—the puns, jingles, nonsense words of inexhaustible significance. How were these to be rendered in a written vernacular associated with any number of dialects, all abounding in homophones, linguistically and culturally unrelated to Victorian English? It is Chao’s solution to this challenge that continues to impress scholars and tickle readers almost a century after the book’s publication.

Chao joined the Berkeley faculty in 1947. By that time, Chinese had been a regular feature of the curriculum for fifty years, due to regent Edward Tompkins’ gift of the Agassiz professorship of East Asian Languages and Literature, the first chair endowed at the University. Tompkins’ primary motive in creating the chair was to benefit the state’s residents and its economy. He had seen trade developing between California and Asia, particularly China and Japan; but he knew that if it was to flourish, California businessmen must understand something of the language and culture of their Asian counterparts. Tompkins had a secondary motive as well. He had seen Asian students and scholars disembark at San Francisco only to board trains to the east, to established seats of learning. Tompkins wanted California, one day, to possess the same intellectual allure and pull. By Chao’s day, it clearly did.

Contribution by Deborah Rudolph

Curator, C. V. Starr East Asian Library

Title: Alisi man you qi jing ji(Search title 阿丽思漫游奇境记)

Title in English: Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

Authors: Lewis Carroll; Yuen Ren Chao 趙元任 (trans.)

Imprint: Shanghai: Shanghai yin shu guan, 1939.

Edition: 4th

Language: Chinese

Language Family: Sino-Tibetan

Source: English-Chinese edition published in 1988 through the Library’s subscription to Chinamaxx (requires Adobe Flash).

URL: http://www.chinamaxx.net

Other online editions:

- Through Library’s subscription to Chinese Academic Digital Associate Library (CADAL) but requires free account creation and Flash).

- Yuen Ren Chao’s papers are housed in the University Archives at The Bancroft Library.

Select print editions at Berkeley:

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

http://ucblib.link/languages

![The Languages of Berkeley [fan]](https://update.lib.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/fan_languages-450px.jpg)